Archive for May 2014

THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS: A usable past

Hellzapopppin’ (1941).

DB here:

By now everybody is used to allusionism in our movies—moments that cite, more or less explicitly, other films. But we tend to forget that movies have been referencing other movies for a long while. One classic form is parody, as when Keaton’s The Three Ages (1923) makes fun of Intolerance (1916). Another example occurs in Me and My Gal (1932). Spencer Tracy tells Joan Bennett that he just saw a movie called “Strange Innertube,” and then Raoul Walsh gives us a comic version of the inner monologues used in Strange Interlude (1932).

Some allusions are in-jokes that sail by most viewers. Almost everybody notices when Walter Burns (Cary Grant) in His Girl Friday mentions that a character played by Ralph Bellamy looks like “that fella in the movies—you know, Ralph Bellamy.” Probably fewer people catch the later line, Walter’s threat to the authorities: “The last man who said that to me was Archie Leach just a week before he cut his throat.” Grant’s real name, of course, was Archibald Leach.

Week-End at the Waldorf (1945) is a sort of updating of Grand Hotel, so when one character remarks that a plot twist “is straight out of the picture Grand Hotel,” we probably catch the self-reference. But the other character piles on the allusions by replying: “That’s right. I’m the baron, you’re the ballerina, and we’re off to see the wizard.” Did people notice MGM congratulating itself twice? And you wonder how many viewers catch the spoiler in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), released only four months after Citizen Kane. Chic Johnson spots a Rosebud sled hanging outside an igloo and remarks, “I thought they burnt that.”

At the beginning of the 1940s, two novice directors seemed to be bringing fresh air to Hollywood cinema. Preston Sturges and Orson Welles were identified with innovative approaches to genre and storytelling. So we might expect them to inject something new into this practice of alluding to other movies. I think they did.

Consider a particular strategy that Sturges and Welles toyed with. Today, we enjoy it when a director treats characters in non-sequel films as sharing a fictional world. Tarantino imagines shifting his characters or brand names (e.g., Red Apple cigarettes) from movie to movie.

When I sell my movies, I retain the rights to characters so I can follow them. I can follow Pumpkin and Honey Bunny or anybody and it’s not Pulp Fiction II.

Jackie Brown (1997) features Michael Keaton as FBI agent Ray Nicolet, who also appears, played by Keaton, in Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (1998). The tactic fitted these directors’ adaptations of novels by Elmore Leonard, who tends to carry over characters from book to book.

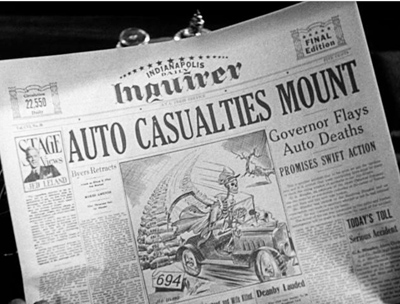

It’s a bit surprising to see this impulse in Sturges and Welles too. The governor and the political boss in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) are McGinty and the Boss in The Great McGinty (1940), and they’re played (uncredited) by the same actors. A newspaper glimpsed in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) contains a column, “Stage Views,” by drama critic Jed Leland, a major character in Citizen Kane (1941).

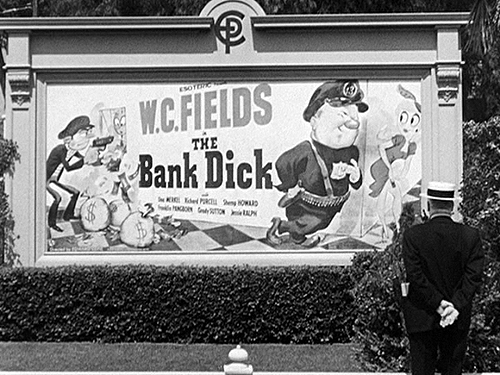

Today fans are used to spotting things that most viewers might not get, but in the early 1940s, it was rarer. I’ve proposed earlier that sometimes Hollywood’s creative community is addressing not the broad audience but its own members, perhaps letting dedicated outsiders “overhear” the conversation. One example would be the nearly-hidden jokes that can be wedged into the background or on the edges of the action. In an entry about a year ago, I considered how sequences around the small-town movie theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek carry barely-noticeable jabs at current films, mostly those by Sturges’ home studio Paramount. And Luke Holmaas has pointed out to me that Hail the Conquering Hero contains a billboard advertising Morgan’s Creek—a sort of joking product-placement. Today, I want to suggest that Welles moved onto the same terrain but followed even more circuitous paths.

The past, not recaptured

Make pictures to make us forget, not remember.

Comment card from first preview of The Magnificent Ambersons, 1942.

The Magnificent Ambersons is, everybody knows, a film about the past. Its story action begins around 1885 and concludes just before World War I. Most of the plot concentrates on the decline of the Amberson family, due partly to financial mismanagement and the willful pride of Isabel Amberson’s son, George Minafer. Parallel to that decline is the development of the town into a city and the rise of the automobile company founded by Eugene Morgan, a failed suitor for Isabel’s hand. A major turning point comes when, after Wilbur Minafer’s death, Isabel is left a widow. She’d like to marry Eugene, but she declines because George is opposed. At the same time, George tries to win Eugene’s daughter Lucy. After the death of Isabel and her father Major Amberson, the family is destitute and George must find a way to support his aunt Fanny. Struck by a car, George is hospitalized, and only then does he reconcile with Eugene and Lucy.

After weak previews, the film was drastically recut, and some new scenes were shot. The original version has not yet been found, so we’re left with a ruined masterpiece. Still, there’s enough there to let us appreciate Welles’s effort to make sense of a crucial period of American history. Old money was giving way to modern, technology-driven fortunes; Eugene’s auto company is the Dell Computers of its day. The film also evokes changes in urban life, with shifting property values and rising pollution shown as consequences of progress. It’s the most downbeat of the “nostalgia” cycle of the 1940s, which includes Strawberry Blonde (1941), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), and Centennial Summer (1946).

Many other films have sought to present the past, recreating the settings and costumes and props of an era. But Ambersons is about pastness. It conveys a melancholy recognition that things are always changing, that we struggle to make sense of events only after it’s too late to affect them. It’s a film centered on missed opportunities and what might have been. Eugene might have married Isabel when they were young, but his drunken serenade turns her against him. If George weren’t such a prig, he might have reconciled himself to Isabel’s remarriage; only at the end, kneeling in prayer, does he seem to realize how his stubbornness cheated many people of happiness. The original ending would have shown Eugene visiting Fanny in a boarding house, with her long and unspoken love for him counterpointing his suggestion that he’s been true to Isabel.

Ambersons carries its sense of an unrecoverable past into the very texture of its telling. At first, the aura of things gone by is given by Welles’ voice-over narration. In affectionate comedy he introduces us to habits and routines of an era of streetcars and changing men’s fashions. After Eugene’s botched serenade, the townsfolk add their voices to the chorus with comments on the scandal. More backstory is given when George is shown growing from a spoiled boy to an arrogant young man. Our narrator recalls “the last of the great Amberson balls.” Eugene arrives, a widower, bringing his daughter Lucy, and George begins to court her that night.

Now the narrator’s past-tense explanation withdraws for some time. Instead, characters take up the burden of narrating the past. “Eighteen years have passed,” says Isabel’s brother Jack at the ball. “Or have they?” Before Eugene dances with Isabel, he remarks that the past is dead. Unfortunately, it won’t stay buried. The old romance between Isabel and Eugene will be rekindled, and bad business decisions and George’s spendthrift ways catch up with the family.

Welles’s plot construction relies on ellipsis. The scenes skip over major story events—Wilbur’s death, the decline of the family fortune, Gene’s second courtship of Isabel, and Isabel’s death. So much occurs offscreen that we are left to play catch-up. We must listen to characters report on what has just happened, or reflect on the more distant past. The film is built on recollection and reaction. We don’t see Fanny at Isabel’s deathbed; she simply flies out of the room to embrace her nephew: “She loved you, George.” We don’t see George and Isabel on their European trip; we learn of it from the doleful Uncle Jack, who thinks that Isabel is falling sick. This refracted narration allows Jack to voice his concern—he’s probably the one Amberson whose judgments we trust—and Gene to display helpless, rigid sorrow at the news.

One of Ambersons’ most famous scenes, the long take of George and Fanny in the kitchen, is characteristic. Under her questioning, he explains that Gene and Isabel were starting to reunite at his college graduation. A peppy nostalgia movie would have shown us that cheerful moment on the campus, but Welles channels the information through George’s insensitive report and Fanny’s uneasy questions—and the scene climaxes with her breaking down in tears. As ever, melancholy wins out. As a result of George’s telling, Fanny will plant the suspicion that gossip about Isabel has been destroying the family’s good name.

Similarly, another film’s finale would show the reconciliation of the young lovers, George and Lucy, in the hospital. Instead Welles’ original script presents that moment through Eugene’s somber report of it to Fanny in her boarding house. (In the version we have, we get the report in the hospital corridor.)

Sometimes, the gaps in time and action are abetted by the studio’s reediting. In the present version, we learn about Aunt Fanny’s failed investments later than in the original version. But even then the information would have been presented after the fact. On the whole, the sense of the sadly unalterable past is built into Welles’ screenplay. As each scene unfolds, we get news about what has happened in the gap since the last scene, or what has happened years before. At the railroad station, Uncle Jack, about to depart, recalls a woman he left here long ago. “Don’t know where she lives now–or if she is living.” Here the pastness he evokes is familiar to us from earlier in the film: “She probably imagines I’m still dancing in the ballroom of the Amberson mansion.” At the limit, Major Amberson’s garbled fireside reverie takes us back to the origins of life: “The earth came out of the sun, and we came out of the earth . . . so–whatever we are must have been in the earth.” Now the past is primeval.

Retro as remembrance

Welles enhances the aura of pastness through specific film techniques. Critics have rightly been alert to creative choices that carry over from Citizen Kane: looming sets, drastic deep-focus cinematography, low angles, chiaroscuro, and long takes, often employing splendid camera movements. But the film displays some unique choices that are, historically, anachronistic.

The most noticeable old-time technique concludes the idyll in the snow. Jack, Fanny, Lucy, and George are riding in Eugene’s horseless carriage. This, one of the few scenes that doesn’t replay the past in its conversation, is given special treatment as a moment out of time. The iris out that concludes the scene is something of a visual equivalent to the old song the riders sing, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”

Similar is the vignetting that softens the edges of the opening sequences, starting with the first shot showing the streetcar stopping for the lady of the house.

Welles’ visual techniques aren’t faithful to the period when the story action takes place. Assuming that the snow idyll occurs around 1904, the iris wouldn’t have appeared in films of that time. And the earlier period of the streetcar shot and changing men’s fashions probably predates the invention of cinema. But by 1942, these techniques were associated with silent film generally and give a cinematic tinge of “oldness” to the action.

I say “by 1942” because recent years had made intellectuals especially conscious of film history. Several books, notably the 1938 translation of Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach’s Histoire du cinéma (translated as The History of the Motion Picture) and Lewis Jacobs’ sweeping The Rise of the American Film (1939) had concentrated on the stylistic innovations of Porter, Griffith, and other pioneers. With some theatres reviving silent classics like Caligari and The Birth of a Nation, cinephiles in urban centers had some opportunities to see silent movies. Most notably, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library was founded in 1935 and under the curatorship of Iris Barry, began building a permanent archive and screening retrospectives.

MoMA also assembled many films into traveling 16mm programs that could be rented by schools, museums, libraries, and other institutions. Silent films also circulated in 8mm and 16mm prints from private companies like Kodascope and Castle Films. Throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, silent comedies were the most popular; Chaplin reissued The Gold Rush in a sound version in 1942. Welles’s interest in silent slapstick is shown in the recently discovered pastiche, Too Much Johnson (1938), which evidently owes a good deal to Entr’acte (1924), a MoMA-canonized classic.

Ambersons offers other, less obvious allusions to old cinema. One cluster of them comes during George and Lucy’s stroll along the sidewalk. George, somewhat petulantly, is insisting that his trip abroad with his mother may last a long time. “It’s goodbye, Lucy.” Angling for a declaration of devotion from her, he gets brittle, agreeable indifference. When he has stalked off, we learn that she is actually quite shaken by the prospect of separation. Watching the dramatic interplay in this long traveling shot, we are probably not likely to pay attention to the posters the couple pass outside the Bijou theatre.

The advertisements announce movies that could have played the Bijou in 1912. The ones in the rear of the lobby are impossible to make out, and there’s one outside I can’t be sure of. (See the codicil.) Raking the frames on DVD and on a good 35mm print, I’ve been able to discern The Bugler of Battery B (1912), Her Husband’s Wife (aka, How She Became Her Husband’s Wife, 1912), Ten Days with a Fleet of U.S. Battleships (1912; in the foyer), and The Mis-Sent Letter (1912). There were several Jesse James films circulating in 1911-1912, but one two-reeler named for the bandit (at the bottom of the second frame here) seems a likely candidate.

These casual background details betray extraordinary fussiness on the part of Welles and his colleagues. Few viewers would pay attention to all the posters, and very few viewers would realize that they’re all from the same year. It’s one thing to include authentic automobiles from the era, as car fanciers would be sure to spot mistakes. But 1912 two-reelers? It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the filmmakers put the posters in to satisfy themselves. (If you’re skeptical, I’d ask: If you’d thought of it, wouldn’t you do it?)

There’s more. The most prominent hoarding advertises a Western, The Ghost at Circle X Camp (1912), from Gaston Méliès. Surely the name also evokes Gaston’s brother Georges, by then an established pioneer of film history and a figure doubtless known to Welles. Is this a sideswiping tribute from one magician-cineaste to another?

There’s also a deliberate anachronism. Tim Holt, who plays George, was the son of action star Jack Holt. A lobby card over the box office announces “Jack Holt in Explosion.”

I can find no trace that such a film existed. Moreover, films of that era seldom identified the main actors in advertising, and in any case Holt was not a featured player in 1912. In order to create an in-joke/homage, Welles seems to have prepared a poster for a fictitious film—as Sturges did with Chaos over Taos and Maggie of the Marines in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek.

Perhaps the most sneaky allusion comes at the very end. After the florid voice-over credits for technical contributions, Welles intones: “Here’s the cast.” Medium-shots of the actors dissolve into one another as the voice-over identifies them. The images recall photographic portraits from the nineteenth century. They also seem to be a variant of those 1930s opening credits that catch the players in shots extracted from the movie to come. Still, there’s something peculiar about these.

Some of the actors look straightforwardly out at us, as we’d expect.

But others turn their heads slightly or shift their gaze, toward or away from us.

Sometimes the shift is tiny, as with the Joseph Cotten cameo. But the tactic is made into a joke when Tim Holt, staying in character, snaps his glance furtively to the camera.

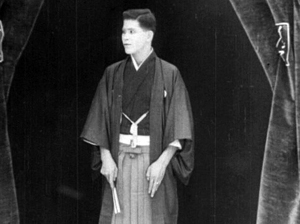

Why these fillips? Here’s my conjecture. Some 1910s films, from both America and Europe, introduced their casts with shots of the actors standing as if on a theatre stage. The actors then looked to left, then right, pretending to take in all sides of a live audience. Here’s an example from Reginald Barker’s The Wrath of the Gods (1914), featuring actor Thomas Kurihara.

None of the 1910s examples I know was framed as closely as Welles’s shots are. But I surmise that Welles offered a modernized variant of a minor silent-film convention. If this is right, it has to be an allusion more far-fetched than even the ones Sturges supplied.

Maybe I’ve gone too far. Once filmmakers start playing these games, overreach is a constant temptation. In any case, I think there’s enough evidence that Welles, like Sturges, was invoking early film history as a way of reinforcing the overall pastness-strategy of his film.

I’d go further and speculate that Welles’s obsessively pinpointed allusions may have stirred a competitive spirit in Sturges. Now we can see the Miracle of Morgan’s Creek tracking shot past the movie house posters as a variant, two years later, of the angle Welles chose for his long take.

And perhaps the audacious inclusion of footage from The Freshman (1925) at the start of The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) was sparked by Welles’ virtuosically faked newsreel in Citizen Kane. As the two boy wonders from the East took advantage of the biggest train set a kid could play with, they may have egged each other on.

For more on the practice of allusionism and world-building see The Way Hollywood Tells It. Thanks to Ben Brewster for information on Jack Holt’s career. My quotation of the Ambersons preview card comes from Simon Callow’s Orson Welles vol. 2: Hello Americans (Viking, 2006), 87.

The Holt and Méliès posters are mentioned in the cutting continuity in Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction (University of California Press, 1993), 214. Alas, the other posters aren’t specified.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster’s illustration, which we can glimpse more fully in a later phase of the shot, shows a man thrashing an American Indian while a woman stretches out her arms in the cabin in the background. At first I thought the first words are The Car, but I can find no film from the period that begins with that phrase. (It would fit more closely with Ambersons thematically than most of the other titles, but in fact “car” wasn’t then a common term for automobile.) Then I thought it was The Coin Box Girl, but again no such film seems to have existed, and that title is hardly in keeping with the illustration. Any ideas?

Yes, I know. Welles would have had a good big belly laugh at these efforts.

P.S. 10 June: I’ve been pursuing some readers’ leads about the still-mysterious poster. In the meantime, Joseph McBride has has corresponded with me with more ideas and information about Ambersons. Joe is the author of many books, including What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career, Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless, and Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit, a meticulous study of those two murders. He is one of the world’s top Welles scholars, so naturally I’m happy to pass along his thoughts.

AMBERSONS is my favorite film, as you probably know, even in its partly ruined state. I think all your analysis is acute, and I like your focus on the self-conscious awareness of pastness that Welles conveys and dissects in the film. The film is redolent of Welles’s youth and even more so of the period before he was born (the period for which I find most of us are most nostalgic). Nostalgia was considered a neurosis in the pre-modern era, a sign of inability to adjust to reality rather than the warm-and-fuzzy state it’s thought of being today. There’s a deep melancholy throughout the film, even if Welles, good magician that he is, distracts us with misdirection via comedy in the beginning while simultaneously laying the seeds of destruction and foreshadowing George’s “comeuppance,” etc.

Last month I was at the Welles conference in Woodstock, Illinois, which has preserved much of its nineteenth-century flavor, including the Opera House where Welles put on TRILBY (but most of the Todd School for Boys he attended is gone). That town and its main square, with bandstand and Civil War monument, seems very Ambersonian as well. I have always seen AMBERSONS as Welles’s most deeply personal film, and his claim that Eugene Morgan is partly based on his father (and that Booth Tarkington knew his father) is noteworthy, as is George Amberson Minafer’s evil-twin resemblance to the young George Orson Welles.

I would only add to your insights that there was much more about the loss of the Amberson fortune in the full version of the film (you allude to that a bit), even though, as you intriguingly note, Welles employs an elliptical style throughout. Welles’s use of ellipsis is Lubitschean (he considered Lubitsch a “giant”), although used for somewhat different reasons, Welles doing so mostly to condense the story in witty ways (and, as you observed to me, focus on characters’ emotional reactions to offscreen events, in the manner of Henry James) and Lubitsch to evade censorship while providing subtle rather than blunt treatments of sex. And some of Lubitsch’s German films, as you know, start with specially posed head shots of him and his main actors, somewhat similar to what Welles does at the end (though he teasingly keeps himself out of frame, partly to stress the voice aspect and also to keep the identification of himself with George stronger). Tim Holt gazing accusingly at us in the end credits is startling — maybe it’s not only to keep him in character but also to say, “I’m you.”

Welles is terrible (archy, corny, and putting on a phony kid voice) as George in the radio version, which, however, is much like the film in some ways. During the night devoted to radio in the 1978-79 “Working with Welles” seminar I co-hosted for the AFI at the DGA Theater, Welles’s longtime associate Richard Wilson and I ran the first ten minutes of the radio show as the soundtrack for the film imagery, and it worked amazingly well. Welles’s use of ellipsis in the film recalls his radio work, in which he and his writers would condense a large novel into one hour, etc. The vignettes at the opening of AMBERSONS are very much drawn from radio. He sold the project to RKO’s George Schaefer by playing the radio show, though the fact that Schaefer fell asleep before the end might have given them pause.

Welles said he included the “Jack Holt in EXPLOSION” gag did to please Jack when he visited the set. Jack was an action star for Capra before AMBERSONS and turns up in THEY WERE EXPENDABLE, in the scene in which John Ford pays homage to his high school teacher Lucien P. Libby by naming a boat after him. Another of those in-jokes that permeate even classic Hollywood, as you say. Mr. Libby influenced Ford’s portraits of Lincoln and other folksy politicians as humorous storytellers.

Welles’s early films show a keen awareness of film history and culture, more than he would let on later he knew at that young age. He described THE HEARTS OF AGE to me as a spoof of THE BLOOD OF A POET and LA CHIEN ANDALOU. TOO MUCH JOHNSON is full of film influences and allusions (I think I sent you my essay on the film from Bright Lights. And KANE has its share of in-jokes, such as Gregg Toland interviewing Kane on board a ship and Kane responding with his first words in the film after “Rosebud” — “Don’t believe everything you hear on the radio.”

Thanks to Joe for corresponding.

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941).

Caught in the acts

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005).

DB here:

If you’re interested in how films tell stories, I think that you’re interested in several dimensions of narrative. Those include the story world (characters, settings, action), narration (how story information is parceled out as the film unrolls), and plot structure (the arrangement of parts).

Plot structure matters because a movie’s parts, like parts of a song or a symphony, help shape our experience. Just as a “curtain line” makes us return after intermission, a cliff-hanging climax to a TV episode makes us tune in next week–or click to continue, if we’re binge-watching. Accordingly, storytellers reflect on how to chop up and lay out sections of their plots. Novelists fret over chapter divisions, TV writers massage their scripts to allow for commercial breaks, and playwrights map action into acts.

The idea of act-structure has passed into commercial screenwriting as well. Just when that happened is hard to say, but certainly by the 1980s scriptwriters consciously broke their screenplays into big chunks. That trend was largely the result of Syd Field’s 1979 book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, although some of his points had been anticipated in Constance Nash and Virginia Oakley’s Screenwriter’s Handbook (1974). From these books came the idea that a feature film script had a three-act structure, measured by time segments (30 minutes/ 60 minutes/ 30 minutes). The prototype was a 120-minute film, with each script page running about one minute of screen time. Field fleshed the model out by noting that “plot points” at the ends of acts one and two turned the conflicts in a new direction. Although other writers argued for other templates, and Field’s model was refined (what’s the “inciting incident” in Act One?), versions of the three-act model still rule the international film industry.

Field presented his anatomy as an analysis of hit films like Chinatown and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He suggested it as a template for a successful plot. As Field’s book gained prominence, his guidelines gave production companies an heuristic for triaging submissions. Now a story analyst could simply check pages 25-35 and 55-65 for turning points, and “incorrect” scripts could be discarded immediately. (But see P.S. below.) Through a feedback cycle, the Field model became a guide to both screenwriters and industry decision-makers. Inevitably, the whole thing got mocked. The day-by-day structure of Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang parodies Field’s scheme, and it closes with a self-conscious epilogue. “So,” says the narrator, “that’s pretty much that….”

To what extent, though, was the three-act structure employed in earlier eras? Field’s original edition drew its examples from current hits, but he implied that classics would display the same underlying architecture. Kristin, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, claimed that four parts were more common than three, and she supported her analysis with examples from films from the silent era and the classic studio years.

But film analysis depends on your perspective. In any movie you can find patterns different from the ones I find, and each of us can make persuasive cases. It would be valuable to know whether American screenwriters in the studio system consciously worked with an act-based model. If they did, what assumptions did they make about the length and organization of each act?

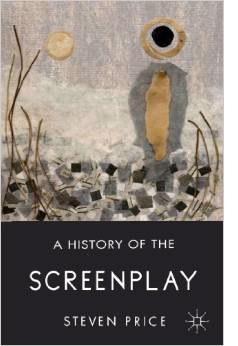

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

For some time, I’ve held the same view. I couldn’t find any script draft broken into acts. Some veteran screenwriters admitted using a three-act model in plotting, but their testimony came long after the era. So, for instance, Philip Dunne says he used a three-act organization for his 1940s screenplays, but he makes the claim in an interview published in 1986. Billy Wilder says he “wrote [Charles Boyer] out of the third act” of Hold Back the Dawn (1941), but the remark comes in an interview given decades later. There’s always the possibility that older writers, newly aware of the Fieldian template, were projecting it backward onto their work—assuring us that they conform to contemporary standards, or even asserting precedence.

Similarly, we can’t rely too much on secondary sources. True, screenplay manuals, from at least 1913 onward, have recommended a three-part structure, purportedy corresponding to Aristotle’s idea that a plot must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But this rests on a misunderstanding. As I’ve mentioned before, Aristotle isn’t talking of acts; ancient Greek plays didn’t have act divisions. And almost none of the manuals use the term “acts” to describe the parts.

Richard Brooks’ novel The Producer (1951), about a weak-willed executive trying to do the right thing, offers some hints along similar lines. He mentions that a screenplay should run to 120 pages, confirming the canonical length that Field proposes. Likewise, Brooks obliquely appeals to Aristotle.

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter has to create a beginning, a middle and an end, and all the dialogue.

Perhaps there’s an intentional irony in the fact that Brooks’ Hollywood exposé is itself broken into three parts, labeled “The Beginning,” “The Middle,” and “The End.”

Unlike many authors of manuals, Brooks was an established screenwriter, and we might expect his novel to refer to acts. It doesn’t. But Lewis Herman, a minor scribe with three screen credits (including Anthony Mann’s Strange Impersonation), does. His 1952 manual declares that a feature-length film is built upon “a three-act theme outline.” The context suggests that the Hollywood studios demand this as a step toward developing a full screenplay. Herman usefully illustrates the outline with a hypothetical example.

Still, manuals or novels aren’t ironclad sources for studio practice. Better would be contemporaneous evidence from memos, story conferences, and similar unpublished documents. Claus Tieber has done extensive research into such sources and has found no discussions of three-act structure. I’ve found a few, but they’re fairly sketchy.

Overseeing Casablanca, Hal Wallis told Michael Curtiz, “The Epsteins have agreed to deliver the film’s ‘second act’ the following day.” Darryl F. Zanuck mentioned the “last act” in correspondence about Viva Zapata! and On the Waterfront. Supposedly John F. Seitz asked Preston Sturges about the flashback structure of The Great Moment: “Why did you end the picture on the second act?” As I noted in an earlier entry, David Selznick’s papers record a story conference on Portrait of Jennie in which Jed Harris remarks: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” He adds that at this point the film “is about 1/3 gone.” This suggests that some practitioners thought of the parts as roughly equal in length. (Kristin’s model proposes that this was the case.)

It may be, of course, that three-act structure of some sort was so ingrained in studio writers’ habits that they didn’t have to discuss it explicitly. Field was addressing aspiring screenwriters who wanted inside knowledge, but as intuitive craft workers, the old contract writers wouldn’t be likely to spell out rigid rules about length and dramatic patterning.

Since corresponding with Steven for his book, I’ve found that one screenwriter explicitly invoked three-act structure in his working notes. And I’m embarrassed not to have noticed it earlier.

Coupling, recoupling, and Joe Breen

F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sheilah Graham.

NICOLAS: Marriage has its phases–its acts–like anything else. This is another act, that’s all.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, screenplay for Infidelity.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Hollywood career was mostly a fiasco. Thanks to temperament, a mentally disturbed wife, bouts of breakdown and alcoholism, and an implacable industry, he worked his way down the hierarchy to unemployment. From July 1937 to his death in 1940, he earned screen credit for just one film, Three Comrades (1938). He also started, but didn’t finish, the best Hollywood novel I know, The Love of the Last Tycoon (aka The Last Tycoon). I think it spells out some features of the Hollywood aesthetic with special vividness.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

Back in the present, to ramp up his mood, Nicolas decides to hold a party in the country estate he had more or less abandoned. At the same time, Althea rekindles her friendship with a former suitor, Alex. She can’t arouse herself to passion, though, and Alex leaves her. As she drives more or less hysterically to the estate where the party is in full swing, Nicolas is wandering through his mansion among the shrouded furniture.

At this point, because of objections from the Production Code office, Stromberg halted Fitzgerald’s work on the screenplay. Aaron Latham’s biography tells us that Fitzgerald had planned to present a reconciliation, in which a photographic trick presents Althea seeing herself as Iris and thus forgives Nicolas. But this ending would suggest that the husband’s sin went unpunished. Fitzgerald suggested an alternative, but this too was rejected by Joseph Breen. He tried to redraft the script later in 1938, but the project dissolved.

Fitzgerald had systematically studied Hollywood releases, even filing plot synopses on index cards. Accordingly, the Infidelity screenplay we have shows an awareness of 1930s storytelling conventions: montage sequences, wordless scenes, and revealing visual detail. We learn that Nicolas’ ardor is cooling when we notice that he has stopped opening Althea’s letters. Fitzgerald’s acquaintance with current trends led him to a thumbnail characterization of Althea’s friend Alex:

He is the type played by Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth–handsome, attractive, worthy, thoroughly admirable, but somehow too heavy in manner to grip the sympathy of an audience if playing opposite a man of charm.

Occasionally, voice-over dialogue in the present is matched with images in the past, in the manner of Sturges’ “narratage” in The Power and the Glory. (See our entry here.) And the large-scale flashback structure, leaving a key action in the present suspended for nearly an hour, anticipates a mode of construction that would be common in the 1940s.

Despite its up-to-date air, the plot of Infidelity creaks a bit. It relies on a great many coincidences and introduces rather late a major menace, a sinister surgeon who seems slated to play the disruptive role of George Wilson in Gatsby. But what’s of special interest to us is a schedule of work that Fitzgerald sent to Stromberg during the planning stages.

Fitzgerald groups his scenes into clusters, and alongside each one he notes a date on which he expects to complete it. Since each scene usually runs only a couple of pages, the groupings present a feasible day-by-day timetable. These clusters of scenes are gathered into eight “sequences,” labeled with Roman numerals. In the 1930s, a “sequence” meant, according to screenwriter Frances Marion, “a series of scenes in which the action is continuous without any break in time.” Each of Infidelity‘s sequences presents a unified phase of the action and is more or less continuous in time, although there are some ellipses as well.

Here’s the news: Fitzgerald’s timetable assembles the sequences into acts. Sequences I through IV are labeled “FIRST ACT 45 pages.” Sequences V through VIII are labeled “SECOND ACT 50 pages.” Sequence VIII is continued to form “THIRD ACT 25 pages.”

The first act establishes the loveless marriage and launches the flashback. While Althea is away, Nicolas re-encounters Iris. Meanwhile, as Althea and her mother are on their way home, they conveniently run into her old beau Alex. Their departure for the United States ends this setup. In the screenplay Fitzgerald has typed: “The First Act may be said to end here.”

The second act develops the conflict to a point of crisis. Althea returns a week early to find Iris at breakfast with Nicolas. She resigns herself to a loveless union. Back in the present, he plans the party and at the instigation of Althea’s mother Alex starts to woo her. But he abandons Althea, and by chance she’s found by Dr. Borden, whom she starts kissing. In the notes for Sequence VIII, Fitzgerald cryptically ends the act on an alternation between the couples:

CUT TO husband and back to old beau [Alex]

[Alethea] with beau [Alex]

Crisis with beau and switch [to the surgeon, Dr. Borden?]

CUT TO husband

After presenting this alternation in scenes, the manuscript concludes:

Full shot of a bedroom, large and luxurious like everything else in this house. Soft lighting, everything covered with cloth or canvas.

Nicolas Gilbert is standing in the middle of the floor.

Close shot of Nicolas.

This is presumably the end of the passage labeled “CUT TO husband.” In the Stromberg schedule, this last portion marks the end of Act Two. Act Three isn’t in the canonical version of the screenplay.

A couple of final points about the structure. Although the screenplay is estimated at 120 pages, its proportions don’t conform to the Field paradigm. At 25 pages or minutes, the third act is short. This is a characteristic of both modern and older Hollywood climax sections. But Act One was projected to be very long at 45 pages, and Act Two approximates it at 50. Fitzgerald’s layout is perhaps more characteristic of a stage play, which can afford a longish exposition and equivalent second act. In the script version we have, both acts run equivalent page lengths.

Fitzgerald may have expected some trimming and compression at later stages. In The Producer, Brooks’ protagonist notes that a 120-page script would usually be cut down to 90 minutes because exhibitors wanted films at about that length. It’s true that few films of the studio era run to two hours.

Set aside brute measurements. What, in Infidelity, makes an act a coherent unit? Not a specific span of time. Act One breaks off partway through the flashback, and Act Two ends before the evening party does. The first act ends when we know a crisis is coming: Althea is returning home early and hasn’t told Nicolas, whom we’ve seen flirting with Iris. Act Two ends at another high point. Nicolas confronts the emptiness of his life without his wife, and nearby Althea is heedlessly making love to a stranger with dubious designs. We could easily imagine the script as a stage play, with a curtain ringing down on each of these teasing situations.

In sum, we have one clear-cut case of a studio screenwriter laying out his plot in three acts. We can’t generalize from a single instance, of course, and we would need many more pieces of evidence to consider this a widespread writing strategy. Perhaps Fitzgerald isn’t typical. Did his relative inexperience as a screenwriter make him rely on a theatrical template that others could do without? Did he employ it more as a rhetorical device to convince Stromberg that the plot was firmly constructed? Still, taken with the reminiscences of Dunne, Wilder, et al. and the sketchy mentions we have in production records, the Infidelity project suggests that some conception(s) of three-act structure were operative in the studio period.

Needless to say, we’ll need even more evidence before we can begin to consider whether the filmmakers’ craft practice matches the structural patterns that today’s analysts disclose in the films. The search continues!

The Fitzgerald outline is reproduced on pp. 161-162 of Aaron Latham, Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood (Viking, 1971). This book is not only a stimulating account of the novelist’s Hollywood years but also a helpful view of the movie colony’s culture. My discussion relies upon the version of Infidelity published in Esquire 80, 6 (December 1973), 193-200, 290-304. It is available in a digitized version here. The original manuscripts are in the University of South Carolina library.

Philip Dunne’s remarks about three-act structure are in Pat McGilligan, Backstory (University of California Press, 1988), 158. Billy Wilder’s remarks come in George Stevens, ed., Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age (Knopf, 2006), 316. (In the same interview Wilder claims that Some Like It Hot has four acts.) Richard Brooks’ The Producer (Simon & Schuster, 1951) is worth reading for its almost documentary survey of the process of production at the period. Lewis Herman’s Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films (World, 1952) is an unusually detailed guidebook.

On Wallis’ memo about Casablanca‘s second act, see Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Visual Design Program of Casablanca,” Post Script 9, 3 (Summer 1980), 38. For Zanuck’s comments see Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years at Twentieth Century-Fox, ed. Rudy Behlmer (Grove, 1993), 173, 226. Seitz’s remark to Sturges about The Great Moment is quoted in James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt, Brace, 1982), 172. There’s more discussion in our blog entry on The Great Moment.

I take Frances Marion’s definition of “sequence” as a bundle of scenes from her How to Write and Sell Film Stories (Covici-Friede, 1937), 373. Tamar Lane offers a comparable definition in his New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936), 123. Interestingly, Lane adds that some scenarists think of each sequence as moving toward a high point, like an act in a play; but this seems only a rough analogy, and the comparison entails that a script would have several more “acts” than three. Steven Price suggests that the “sequence” as an extended script segment emerged in the silent period and hung on in some sound screenplays; see A History of the Screenplay, especially 63, 115-116, and 153-157. At the same time, “sequence” could refer to a single brief segment, as in “action sequence” or “montage sequence.”

Thanks to Steven Price and Claus Tieber for correspondence about act structure. Claus has a relevant case study of Grand Hotel, “‘A Story Is Not a Story But a Conference’: Story Conferences and the Classical Studio System,” in Journal of Screenwriting vol. 5, no. 2 (2014): 225-237. More generally, I’m grateful to researchers at the Screenwriting Research Network for what I’ve learned from their conferences in Brussels in 2011 and in Madison in 2013.

Other entries on this site have considered act structure. Kristin explains her model, based on goal formulation and injections of new information. She expands on this as it affects character subjectivity and point of view. I illustrate her model with reference to what is supposedly the most wayward and narratively fragmented modern genre, the action picture. I offer some general reflections on how the four-part structure informs not only current films but best-selling novels. For a more general discussion of the dimensions of film narrative, you can download this chapter from my Poetics of Cinema. Also, too: there’s the precept that form follows format. Finally, I consider modern trends in screenplay construction, including act structure, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

After a while you see the triplicate scheme everywhere. In Case History of a Movie (1950), p. 30, Dore Schary says that Charles Schnee turned in the script of The Next Voice You Hear in thirds. Acts? I’ll have to get back to you.

P.S. 19 May 2014: In reply to this post, Greg Beal comments that my discussion of rejecting screenplays based on Field’s plot points is inaccurate.

My claim was, I now think, an overstatement. I should not have suggested that the absence of canonical plot points would be sufficient to doom a screenplay. Naturally, I realize that the analyst would still be obliged to write fuller coverage. I meant simply that the Field template could set up expectations that the script wasn’t written to standard. Other factors would surely be taken into account in a final decision. The larger point, that three-act structure along Field’s lines shapes analysts’ judgment, remains to be determined.

My most concrete evidence for the saliency of the three-act, plot-point model in this production context comes from two manuals by story analysts. T. L. Katahin’s Reading for a Living: How to Be a Professional Story Analyst for Film and Television (Blue Arrow, 1990) recommends that analysts look for three acts, including a ten-page initial setup followed by a development and two further acts that forward the protagonist’s goals. But Katahin doesn’t propose exact page counts for further twists.

More specific is Jennifer Lerch’s 500 Ways to Beat the Hollywood Script Reader: Writing the Screenplay the Reader Will Recommend (Simon and Schuster, 1999). In following the three-act layout, she suggests that Act One, the setup, be consummated between pages 20 and 30 (ideally consisting of two scenes 10-15 pages each). Act 2, as per Field, is said to run long, up to pages 80-90, and typically consists of four to eight sequences (each 10-15 pages or so). This act is said to lead to a point of no return, the pivot-point for Act 3.

Lerch, who was a professional story analyst for the William Morris Agency for eight years, claims, “Your script’s setup can literally make or break your project in the Hollywood Reader’s eyes, particularly at some companies that instruct readers to stop at page thirty of a script if it looks substandard. You may have a great second act and climactic sequence, but Hollywood will never see it unless you give it a savvy setup” (91). Passages like this one led me to think that the Field template weighs quite strongly in analysts’ judgment. But I’ve never supervised story analysts, so I welcome Greg’s expert comment on the matter.

P.P.S. 20 May 2014: More information on Fitzgerald’s Infidelity screenplay and its act breaks. In a letter to Hunt Stromberg dated 22 February 1938, Fitzgerald wrote:

The first problem was whether, with a story which is over half told before we get up to the point at which we began, we had a solid dramatic form–in other words whether it would divide naturally into three increasingly interesting “acts” etc. The answer is yes. . . .

This point, the decision to sail, also marks the end of the “first act.” The “second act” will take us through the seduction, the discovery, the two year time lapse, and the return of the old sweetheart–will take us, in fact, up to the moment when Joan [later, Althea] having weathered all this, is unpredictably jolted off her balance by a stranger. This is our high point–when matters seem utterly insoluble.

Our third act is Joan’s recoil from a situation that is menacing, both materially and morally, and her reaction toward reconciliation with her husband.

Evidently the timetable reprinted in Crazy Sundays was prepared after this letter was sent. This letter is printed in F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (Scribners, 1994), 348-349.

P.P.P.S. 30 May 2014: I always enjoy getting correspondence from readers, and I must catch up by noting some other responses I’ve received. David Cairns, whose wonderful blog Shadowplay is always worth checking on (his latest post is on Hannibal, the TV show), writes with this comment:

Hold Back the Dawn (1941).

Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image

Sansho the Bailiff (1954).

DB here:

First things first: Happy birthday, Mizo-san! (He was born on 16 May 1898.)

Secondary things second: This entry is based on a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, as part of its comprehensive Mizoguchi retrospective. I want to thank my friends David Schwartz and Aliza Ma for inviting me to MoMI.

A fragile and fragmentary legacy

Mizoguchi, age twenty-eight, and Sakai Yoneko at Nikkatsu studio, 1926.

Mizoguchi Kenji’s renown in the West has flowered and faded. Like other Japanese directors, he was unknown in Europe and America before 1950. When Rashomon won the Golden Lion at Venice that year, Japanese cinema sprang onto the world’s radar. Just two years later, Mizoguchi began winning top Venice prizes with Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). His old associate Nagata Masaichi saw export opportunities in Japanese costume pictures, especially after Gate of Hell (1953) won the Academy Award, and so Mizoguchi turned out several historical films with high-tone production values. He died in 1956, after Street of Shame (1956), a return to contemporary social commentary.

In just five years, this flare of attention and the praise of the Cahiers du cinéma critics made him second only to Kurosawa in Western recognition. During the 1960s, while Japanese critics were writing him off as outdated, international critics canonized him. Here’s Andrew Sarris in 1970.

I recently saw an obscure Mizoguchi film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art without any English subtitles, which left me up the Sea of Japan without a paddle. The program notes alerted me to the plot outline, but I was generally puzzled by the personal relationships, and the picture dragged along. . . . And then at the end the beleaguered heroine walks to a restaurant on a hillside overlooking the sea, and she orders something from a waiter in white, and the camera is high overhead, and the morning mists are bubbling all around, and the camera follows the waiter as he walks across the terrace to the restaurant and then follows him back to the heroine’s table now magically, mystically empty. It is as if death had intervened in the interval of two camera movements, to and fro, and the bubbling mists and the puzzled waiter provide the Orphic overtones of the most magical mise-en-scène since the last deathly images of F. W. Murnau’s Tabu.

Mizoguchi’s reputation was based almost completely upon his 1950s work. But as ever, film distribution shaped film tastes. Soon after the 1972 success of Tokyo Story in New York, Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films began circulating many major Japanese titles. Most electrifying for my generation was an abundant set of Ozu films, the arrival of which coincided with Donald Richie’s Ozu (1974). Twenty years after Mizoguchi’s emergence, Ozu began his ascent to the top of the pantheon.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

A broader recognition of 1930s-1940s Japanese film was crystallized in the 1978 publication of Noël Burch’s book To the Distant Oberver: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film. Burch urged the case that Ozu, Mizoguchi, and other “mature” directors had done their most ambitious work well before the Western festivals and critics had caught up with them–that in fact the venerated postwar films were mannered and unadventurous compared to the artistically radical prewar work.

Since then, as Ozu (and Naruse, and many more) have risen to the pantheon, Mizoguchi has become quite obscure. Critics haven’t really boosted him much; his most famous film, Ugetsu, ranked 50th in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. Nor is the range of his work easy to sample on video. In 1976, Kristin and I were obliged to go to London to see the early Ozus not in US distribution; now, everything is on DVD. But many years later I went to Brussels for a complete Mizo retrospective, and the rare titles I saw there remain nearly unknown. His festival classics and the “Talbot canon” circulate on good-quality prints and DVDs, thanks to Criterion and Janus. But other films must be hunted down in obscure foreign DVD.

Worst of all, the survival rate of Mizoguchi’s films is appalling (although not exceptional for Japan). He made 43 films between 1923 and 1929; of these, only one survives complete. For the rest of his career he made or contributed to 42 features, of which we have 30. We lack over half his output. The physical quality of what we have varies a great deal, from gorgeous (Genroku Chushingura) to appalling (The Straits of Love and Hate, 1937, blown up from a scratched and contrasty 16mm copy). In fact, copies seem to have deteriorated. Prints I saw in the 1970s of Oyuki the Virgin (1935) were in decent shape, but many copies circulating now seem to be bad dupes of those prints, now much battered. There seems to be no systematic effort to restore what we have.

Tears are easy; tragedy is hard

I can’t deny that Mizoguchi’s fluctuating reputation is due to more than availability. He is easier to admire, even to worship, than to love. His films, though visually sumptuous, can be somber and bleak. Often unremitting tales of suffering, they lack humor (though not irony). Ozu’s mix of poignancy and comedy is much easier to enjoy than Mizoguchi’s forbidding, near-tragic despair. Ozu is also a more rigorous stylist; his signature is in every frame. While Mizoguchi was no less distinctive, he was more pluralistic in his technique.

Another obstacle: despite working with melodramatic material, Mizoguchi cools it down, sometimes to the point of remoteness. For many of his films, the prototype was Japan’s shinpa drama, an early twentieth-century theatrical tradition that blended kabuki themes and situations (e.g., the conflict of love and duty) with Western-style dramaturgy. Shinpa plays tended to concentrate on the sufferings of women in a male-dominated society. Shinpa women are victimized, exploited, and condemned; when they sacrifice themselves for men, too often the men attack them, betray them, or dump them. Mizoguchi worked many variations on these plot elements. When the American Occupation demanded more liberal films from the industry, he simply let the oppressed woman win some victory in the end.

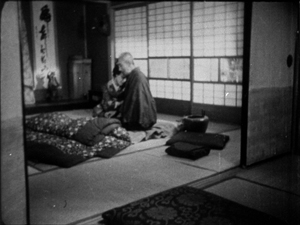

Whether the woman wins or loses, Mizoguchi refuses to beg for tears. Some directors, notably Sirk, amp up melodrama; others, like Preminger, bank the fires. Mizoguchi seems to try to extract the situation’s emotional essence, a purified anguish, that goes beyond sympathy and pity for the characters. In The Poppy (1935), here’s how he renders the moment at which a father and daughter learn that the daughter’s suitor has abandoned her. The core dramatic action is the daughter moving from the foreground to console her father, at which point they embrace.

Some climax! No close-ups, no fast cutting, no camera movement; people withdraw from us and leave us on the outside. All of which suggests that one dimension of Mizoguchi’s artistry consists of exploring how human emotions, notably the unhappier ones, can be expressed in vivid, sometimes surprisingly “cold” pictures.

Pictures tell the story

Everybody grants that Mizoguchi makes magnificent images. He has gone down in history as a pictorialist. But his pictorialism is of a peculiar kind. We tend to think of pictorialist filmmakers as, for instance, masters of landscape, like Ford in My Darling Clementine; or exponents of abstract patterning, like von Sternberg in Shanghai Express; or buccaneers of aggressive depth, like Welles in Citizen Kane.

On each of these possibilities Mizoguchi can match the masters. Here’s a landscape from Portrait of Madame Yuki (1950; this is the scene that made Sarris swoon), a geometrical shot from Hometown (1930), and a bold depth composition from Naniwa Elegy four years before Kane.

It’s not surprising that Mizoguchi relies on the image; in his youth he studied painting (interestingly, Western-style painting at that). But he is, I think, a more fervent pictorialist than his peers.

Most movie scenes consist of a story situation mapped onto the space; the style follows, emphasizes, or shapes the story’s presentation. Suppose, Mizoguchi seems to ask, that we start with an image and ask it to become a drama. That’s in a sense what seems to happen with the Poppy example above: a striking picture develops into a story through a suite of compositional changes. Or consider this, from Sansho the Bailiff. A scene starts with a bundle of brush in a village street. Gradually it becomes the site of action: two children peep out, one by one.

Our view isn’t impeded only by the brush. A man bursts eagerly into the frame, blocking the boy and girl, followed by another man. The camera tracks a bit around the foreground post. As the scene goes on passersby will intrude into the frame.

You can’t, I think, imagine many more ways to suppress our views of the kids. We strain to see past all these obstructions, and when the view finally clears and the children are visible and come forward briefly, they turn from us…and more people pass in the foreground.

This is actually an important moment in Sansho the Bailiff: The children, kidnapped from their mother, are about to become slaves. It could be rendered with all the stops out, as a scene of brutality or high tension, but instead Mizoguchi let the dialogue (after some delay) explain what’s happening. At first you might think that Zushio and Anju have escaped from their captors and are in hiding; the unfolding image initially permits that possibility. Eventually, though, the shot, expressing the children’s fear and shame as they shrink from not only the men but the camera, holds us in its own right.

Instead of an image that is a vehicle for the story, the story is gradually born out of the changing image. To some degree, this happens in many films, but not with the persistence and rigor we find in Mizogcuhi. He talked of wanting to hypnotize the viewer, and this is done, I think, as much by the minute changes in the pictures as by the dynamics of the drama.

This version of pictorialism employs several strategies. I’ll mention just three.

Now you see it, sort of

Kiyonaga Toru, Interior of a Bathhouse (1780s).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Traditional Japanese cinema is itself heavily pictorial, from the zigzag excitement of the 1920s swordplay films to the dynamic modernity of the city dramas and the monumental gravity of historical dramas. Directors, I’ve argued in various places, cultivated a “decorative” approach to technique. Composition, camerawork, cutting, and other tactics often created flashier compositions than we find in other national traditions. As early as 1922, Ikeda Yoshinobu was creating arabesques with a bedstead, framing the faces of grieving family members (Cuckoo).

The gridded zones of the Japanese house seems to have invited filmmakers to explore a sort of Advent-calendar style, with bodies framed in different apertures (The Abe Clan, 1938). The same idea could be applied to a bar’s Art Deco wall divider (First Steps Ashore, 1932).

I’ve also argued that this love of pocketed compositions may be an effort to echo similar impulses in Japanese graphic art. The Kinoyaga woodblock print above, with its partial views of women bathing and the little windows through which we see the male attendant watching, is a beautiful example. Perhaps filmmakers adapted this eye-beguiling tactic as a way of giving cinema some cultural credentials (if not a national identity).

Most directors don’t sustain such flashy compositions. The shots function mostly as long-shots or establishing shots, or as in the Cuckoo example, as a series of brief extracts from the larger scene. Mizoguchi drew upon this decorative tradition but let it be sustained through figures moving into and out of the apertures within the frame. He creates a game of vision, a sort of fluctuating pictorial vividness that conceals or reveals or teases us with information.

One of the most vivid examples comes in this famous scene from Sansho the Bailiff. Tamaki’s leg tendons are cut, and the other enslaved women are forced to witness it. As the struggling Tamaki is peeled away from the wall and the slavemaster walks to her offscreen, the other women become visible and an older master comes slightly forward in the central square Tamaki had occupied.

As she screams, the grid isolates each woman’s fearful turning away. As with the earlier Sansho scene, dialogue comes to “button up” the unfolding of the image: The old man tells the cringing women that all runaways will punished this way.

The impact of the act is amplified not by, say, cutting to different women’s reactions, but by letting us see them all, simultaneously, in a choreography of terror.

Mizoguchi finds an abundant variety of ways to play his game of vision. Not only are figures and faces secreted in various pigeonholes of the frame, but he can tease us with some that are merely shadows or partial figures (The Poppy; Tokyo March, 1929). Sometimes the key element, such as a character’s reaction, is obscured by a semi-transparent surface, as when the embarrassed model is caught in a corner of a screen in Utamaro and His Five Women (1946).

What other directors treated as piquant flourishes, imaginative ways to arouse our visual interest before moving in to closer views, Mizoguchi saw as a way to activate any cranny of the image and invest it with expression. But for that process to unfold, he needed time.

Intensify and prolong

From the brief surviving fragment of Tojin Okichi (1930).

During the course of filming a scene, if an increased psychological sympathy begins to develop, I cannot cut into this without regret. I try rather to intensify and prolong the scene as long as possible.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Mizoguchi is famous as an exponent of long-take shooting. His earliest surviving film, Song of Home (1925) displays the Hollywood-style editing that most Japanese filmmakers mastered at the period. At some point–he says it was while shooting Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner)–he began using a method he called “one scene, one cut.” (Here “cut” apparently refers not to a shot change but to a single take, like a “cut” of meat. Hollywood filmmakers talked the same way sometimes.) That would suggest that he took every scene in a single shot, but actually he didn’t. Most of his scenes are built out of several shots, and throughout his career he would have recourse to standard analytical and shot/reverse-shot cutting for many sequences. He wasn’t as strict about the plan-sequence as, say, the Miklós Jancsó of the 1960s and 1970s was.

Still, he definitely used longer takes than most filmmakers of his day. The shots in most of his post-1935 films average between twenty-five and forty seconds in length, which means that some shots run minutes. Many of his long takes are made from static camera positions, as in the above examples. But he didn’t shrink from camera movements, either tracking shots or crane shots. Kristin and I discuss an example from Sisters of Gion in Film Art, and in his later films he enjoyed establishing a setting with a high-angle crane shot before moving in to details. He also enjoyed riding the crane and directed from it even if the shot was static.

Fixed frame or moving shot, Mizoguchi’s long takes can extract an arc of pictorial-dramatic intensity. That arc can have a clear-cut ABA pattern. In My Love Has Been Burning, the liberal feminist Eiko finds her weak lover Hayase drunk and despondent. He’s no longer the idealist she thought he was, but he defends himself as changing with the times.

Hayase says he’s got some money now and they can marry. When she doesn’t warm to the idea, he attacks her, and suddenly her face gets enlarged, upside down, when he slams her to the floor. This is the first high point of the scene.

They struggle out of frame, but Mizoguchi doesn’t follow them.

Immediately there’s a second assault on our vision: a screen abruptly crashes into the foreground.

After it settles into place, Eiko flees back into the frame, pausing by the doorway. She leaves, and Hayase totters to the same spot looking after her.

The shot has built up to one spike, the image of Eiko on her back, her face close to us, and then to a second, with the collapsing screen. At the end, the site of action returns to the beginning: a figure near the doorway, something else (Hayase, the screen) in the foreground. But in the course of this ABA pattern, the game of vision has concealed as much as it has revealed.

Throughout his career Mizoguchi experimented with the patterning of his long takes, often building them around advances to and away from the foreground, as in these examples. This tactic can be seen in a pure state in the most intense scene of the Occupation feminist film Victory of Women (1946). Here the characters rush the camera and shrink from it as the emotional pitch rises.

Tomo’s husband has just died, and she has already told her friend the lawyer Hiroko that she has no more milk for her baby. Tomo calls on Hiroko, who invites her to come in. The camera obediently tracks back as she enters and sits.

Hiroko, at first oblivious to the distraught Tomo, begins to question her. At first Tomo says that nothing has happened to her baby, and she slides away from Hiroko. She tells her that her husband died the day that they had met in the street. She edges closer to the camera.

Sobbing, she tells Hiroko that the baby is dead; he died sucking her breast. She falls out of the frame and as the camera pulls back Hiroko bends to comfort her. But she also asks Tomo to tell her exactly what happened.

Tomo confesses that staring at her crying baby, she hugged it so close that she may have killed it. As she rises, she cries, “My baby!” And she turns and staggers, like Ayako in Naniwa Elegy, to the most distant point of the set–as if hoping to escape both Hiroko and the camera.

Track in as Hiroko goes back to her, at the spot at which the shot’s action started. Once more the two women advance to the camera, with Hiroko nearly dragging Tomo back to the center. But when Hiroko suggests she go to the police, Tomo slides quickly away from her, back to us, and the camera abruptly pulls back to accommodate her. As when the paper wall crashes into the frame in My Love Has Been Burning, a spike in the drama is accompanied by a second burst into the foreground.

Hiroko rushes to embrace Tomo, assuring her that “You must not run from life, but face it!” Mizoguchi’s staging favors the doubt and fear on the face of Tomo, not the somewhat complacent Hiroko.

As Hiroko hurries off to dress for going out, Mizoguchi’s camera lingers on Tomo, not only pitiable but justifiably worried that she is condemned. As she bends and glances to and fro, Mizoguchi ends the seven-minute scene on an image of a woman with nowhere to turn. This is a terrifying final image: Is this what Hiroko meant by “facing life”?

Some of Mizoguchi’s earlier works go further still. Instead of a coming-and-going pattern, in which the characters confront the camera and then retreat, we get a going-and-going one. The most famous, about which I’ve written probably more than I should, comes in Naniwa Elegy, when Ayako, telling her boyfriend of her sexual infidelity, retreats from him, and from us.

A Western director–Wyler, say, as in The Little Foxes, or Huston–would have put the camera at exactly the opposite point, in the corner of the wall, so that Ayako would advance toward us and Nishimura’s reaction would be constantly visible in the background. It’s as if Mizoguchi anticipated such full-disclosure framing (before these men had even made their films!) and dismissed it as too easy. By suppressing characters’ expressions, he throws our attention onto Ayako’s voice and her posture, while also sustaining some suspense about how Nishimura will respond to her revelations.

Mizoguchi finds a huge variety of ways of turning images into drama, and he has left us a rich repertory of staging strategies–if we only look. Young filmmakers, are you looking?

Filigree

Tanaka Kinuyo and Mizoguchi Kenji in Venice, early 1950s.

[The long take] allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Once Mizoguchi enhances the decorative frame with surfaces and holes bristling with possibilities, and once he sustains it in time through the long take, he can build his scenes out of slight changes in the image–changes that add nuance and expressive depth to the drama. We’ve seen this already in several passages, but I want now to stress how this sharpens our attention and engagement. The restraint of Mizoguchi’s handling (restraint within sumptuousness, I should say) trains us to watch for the tiniest shift in pictorial emphasis. This is the third strategy I want to mention.

In Lady of Musashino (1951), minor changes around the deathbed drive our eye to the profile of the dying Michiko.

Likewise, when Oishi in Genroku Chushingura reads the master’s poem, sent to his vassals after his suicide, he lowers the paper just a little at the climax, and the gesture is echoed in the men’s slumping forward even more. (This is a movie largely made of just-noticeable differences.)

The just-noticeable differences can be triggered by tiny changes in the avenues of our vision. In Street of Shame, the brothel owner, turned from us in the middle ground, first reveals Mickey and the delivery boy down the left corridor. When he shifts his head, Mizoguchi closes off that view and allows faces and bodies of the prostitutes to fill up the corridor on the right.

Bolder movements can yield even briefer glimpses. When Oharu reads the message from her dead lover, Mizoguchi gives us a “decoy” shot: Her mother stands guard on the left and in the distance we see the door through which the father is expected to come. But the scene’s real action is taking place behind the hanging kimono, where Oharu reacts painfully to the letter. Since we can’t see her, only her wavering voice and the trembling of the kimono convey her emotion. Suddenly she starts to thrash around, her mother leaps toward her, and a tussle ensues. The kimono is pulled down in a heap.

What’s all the fuss? What is Oharu doing? The answer is given to us in an almost subliminal detail, the knife that flashes through the lower right corner of the shot in only two frames on the 35mm print. Oharu races out of the shot, bent on suicide.

So the nuances that spring up may be protracted or simply glimpsed, but either way they become the product of the image giving birth, through its transformations, to the drama. The strategy is just as applicable to closer views as to long shots. In one scene of Woman of Rumor (1954), the keeper of an elegant brothel notices a young man getting cozy with her daughter. The tension is exacerbated by the fact that she hopes to nab Dr. Hatoba herself. As the two talk, Mizoguchi buries Hatsuko in the rear of the scene, her presence signaled by a shadow and her kimono sleeve poking out from a screen.

Mizoguchi cuts directly in and provides a medium-shot of Hatsuko peeking. This might seem safe and conventional, especially in the light of daring choices like those made in Naniwa Elegy. But Mizoguchi now wants to trigger the game of vision around the woman’s face and the edge of the screen. As she listens, he teases us with a little suite of changing expressions and minute gradations of partial blockage–a sort of pictorial vibrato.

As Hatsuko edges out to approach the couple, Mizoguchi switches our attention to small, nervous hand gestures.

Once installed behind the couple, Hatsuko starts the whole process again, from eye-catching sleeves to peekaboo eavesdropping.

Mizoguchi was a fairly pluralistic filmmaker, so the strategies I’ve itemized don’t exhaust everything we encounter in his movies. Sometimes he builds scenes in a fairly orthodox way, with traditional framing and cutting. But taken as a whole, his films offer a magnificent repertory of ways in which the image can, under pressure, deepen and enrich a dramatic situation. Unlike most of today’s filmmakers, he cares about rigor, nuance, and austerity–while at the same time working with scenes of intense emotion. Admire him, worship him, love him, or just respect him: film culture can’t live fully without him.

Thanks, over forty years of viewing, to the Japan Society of New York, the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute (formerly the Japan Film Library Council), Dan Talbot and José Lopez of New Yorker Films, and the Brussels Cinematek, especially Gabrielle Claes.

The MoMI series runs until 8 June. It begins on 16 May at the Harvard Film Archive and on 19 June at Pacific Film Archive. For Fandor’s Keyframe daily, David Hudson has a varied roundup of response to MoMI’s series.

Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema offer many Mizoguchi films on DVD, some on Blu-ray. See also Criterion’s Hulu Plus offerings. Digital Meme sells DVDs of some early Mizoguchis, with benshi accompaniment; the exasperatingly brief fragment of Tojin Okichi is on volume 2..

My quotation from Andrew Sarris comes from “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970,” in The Primal Screen (1973), 60-61.

Good clichés will never die as long as journalists need to crank out copy. The MoMI retrospective has revived the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi tug-of-war, this time among New York critics (here and here). Such sideswipe critiques and hosannas can’t really be backed up within the space limits of popular publishing. Moreover, I think that such quick assertions of taste block close consideration of the work. Once you’ve dismissed a filmmaker, you’re unlikely to probe further, and your readers will probably be even less curious. I defected years ago from the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi skirmishes.