Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book

Friday | June 20, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

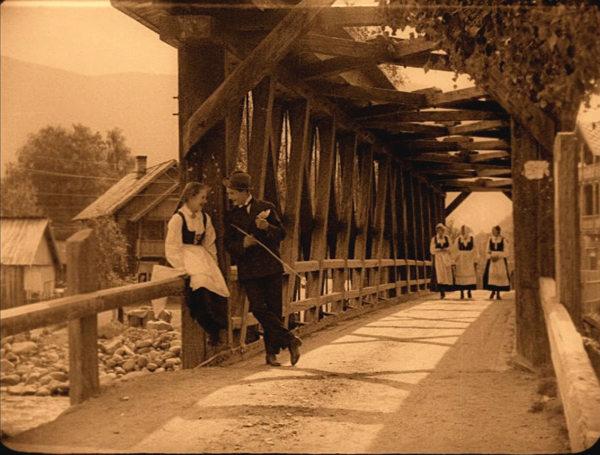

Gipsy Anne (1920).

Kristin here:

A stack of new DVDs/BDs and books has been gradually building up on the floor in a corner of my study. I’ve been meaning to blog about them, but first I had to catch up with viewing and reading. Or did I? With this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato starting next week, I suddenly realized that the DVDs at the bottom of the pile were ones I bought there last year! Clearly, I would never catch up.

So this entry aims to notify you of releases, many obscure, that you may so far have missed. Mostly the DVDs and BDs come from the dedicated archives and independent home-video companies that release historical rarities and restorations.

Early Scandinavian films

I don’t think I had ever seen a Norwegian silent film, apart from the one Carl Dreyer made there, Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1925). Though produced between Master of the House and the wonderful La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, The Bride of Glomdal is unquestionably one of Dreyer’s lesser works.

In the sales room at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, one stand was selling four new releases of Norwegian and Swedish silent and early sound films. All were issued by the Norsk FilmInstitutt.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

This is the only one of these Norwegian films that I have so far watched, and it’s a remarkable one. Clearly Breistein and his cinematographer Gunnar Nilsen-Vig were influenced by the great Swedish films of Sjöström and Stiller, and though Gipsy Ann is not up to the best work of those two, it shares the same feeling for landscape for for allowing a melodramatic situation to develop slowly and in unexpected ways.

It tells the story of a foundling child, Anne taken in by a widow who owns a large farm and who raises the girl alongside her son, Haldor. Haldor is a timid boy, constantly led astray by the adventurous Anne. Once they grow up, the two fall in love, but Haldor’s mother pushes her son into an engagement with a young woman from a well-to-do family. In the meantime, Jon, a humble tenant farmer working for the widow, falls in love with Anne, who snubs him.

Gipsy Anne has none of the clumsiness in lighting and staging that one so often sees in European films of the period around 1920. The cinematography is beautiful, as the frame at the top shows. Breistein has mastered shot/reverse shot and other aspects of analytical editing. The lighting is impressive, with some interiors using a strong backlight through windows and a soft fill that gives a sense of realism (left).

The film also sets up neat visual parallels. In a scene in Anne’s childhood (below left), she hides by an old farm building and curiously spies on some local lovers. Much later, she lurks heartbroken by Haldor’s lavish new house as he shows it to his fiancée:

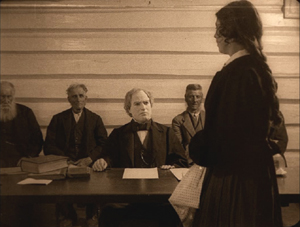

There are even some planimetric shots that yield dramatic compositions, one when Jon comforts the young Anne when she learns that she was adopted, and another, much later, when Anne is in court testifying about the fire that burned down Haldor’s new house:

Again there is a parallel, since Anne is hiding her own guilt in starting the fire, and Jon is about to falsely confess to the crime to protect her. (There’s also a hint at influence from Dreyer in that courtroom shot.)

Of the four releases, Fante-Anne is the only one put out in a Blu-ray version, packaged along with a DVD and an informative booklet in Norwegian and English. The print, with toning and a pleasantly rustic-sounding score, has English subtitles. Oddly enough, the Norsk Filminstitutt does not have an online shop. The film is available from at least two Norwegian online dealers in Scandinavian videos, Nordicdvd and Dvdhuset. It can also be ordered from an American source, Blu-ray.com.

Markens Grøde (The Growth of the Soil) was made only a year later, in 1921; it was directed by Gunnar Sommerfeldt and is another rural melodrama, adapted from a Nobel Prize-winning novel of the same title. This release is 89 minutes long and includes subtitles in English, French, Spanish, German, and Russian. It, too, can be ordered from Nordicdvd and DVDhuset.

The third release is an epic film, Brudeferden i Hardanger (The Bridal Party in Hardanger, 1926). Its two parts run 104 and 74 minutes; it was also directed by Rasmus Breistein, with cinematography by Gunnar Nilsen-Vig. DVDhuset carries it, but not Nordicdvd. It is, however, available from Amazon.uk. It has English subtitles.

Finally there is “Bjørnson på film,” a compilation of three early films based on the pastoral writings of Nobel Prize-winning author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and was issued in 2010, the centenary year of the author’s death. Two of these are Swedish productions: Synnøve Solbakken (1919, director John W. Brunius) and Et Farlig Frieri (A Dangerous Proposal, 1919, director Rune Carlsten). Lars Hansen stars in both, and Karin Molander co-stars in Synnøve Solbakken. The third is an early Norwegian talkie, En Glad Gutt (A Happy Boy, 1932, director John W. Brunius).

After considerable searching, I can find no online source for this 2-DVD set. Perhaps it will become available. Otherwise you’ll have to come to Il Cinema Ritrovato and see if it’s on sale again. If not, at least you will have a great time!

All these releases are PAL, though Fante-Anne is also Blu-ray region B; they would all need to be played on a multi-standard machine.

(Mostly) American treasures

The well-known and invaluable “Treasures” series from the National Film Preservation Foundation has become somewhat difficult to keep track of. It started with “Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films.” That was followed by “More Treasures from American Film Archives: 1894-1931.” After that volume numbers appeared, and the references to archives were dropped in favor of thematic collections: “Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film 1900-1934” and “American Treasures IV: Avant Garde 1947-1986.” Then Roman numerals disappeared with “Treasures 5: The West 1898-1938.”(The ones linked are still in print.)

Now we have an unnumbered entry, but it’s still part of the series: “Lost & Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive.” Most readers will recall that in 2010 it was announced that about 75 films had been found in the New Zealand Film Archive. News coverage mostly centered on John Ford’s 1927 feature Upstream, which had up to that point been lost. That film forms the central attraction for this new release.

It also includes, however, an incomplete print of a distinctly non-American film, The White Shadow (1924). It was directed by Graham Cutts, but it is mainly of interest now as a film on which the young Alfred Hitchcock worked in several capacities. He wrote the script, based on a novel, and was assistant director, editor, and art director. Despite the enthusiastic tone of the program notes in the booklet accompanying this set, there is little detectable of the later Hitch. The story is ludicrously far-fetched, depending on the old good twin/bad twin contrast, with Betty Compson in both roles (above). At various points the twins pretend to be each other, much to the confusion of the bad twin’s fiancé, played by Clive Brook. The convoluted plot becomes even more so when a series of titles tries to convey the action of the missing final three reels.

The film has its moments. Cutts, who was a decent if not outstanding director, manages some lovely compositions, as with the backlighting in the night interior below left. As with many of Hitchcock’s sets for the film, this one is pretty standard-issue. He obviously had some fun with the set for the tavern called The Cat Who Laughs. It looks a bit jumbled, but it’s actually full of little areas that Cutts uses effectively for picking out pieces of action amid the chaos:

So the Treasures series moves on, as does the Foundation. Not all of the discovered prints made it onto the DVD set. Several more have been preserved since and generously made available for free online viewing at the Foundation’s website; more will be added as the restorations are completed.

Blu-ray USA

American classics continue to make their way onto BD.

Flicker Alley has teamed with the Blackhawk Films Collection to release The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923, director Wallace Worsley). No original 35mm negative or print is known to survive, so this release was mastered from a 16mm tinted copy struck at some point from the original negative. Some restrained digital restoration was done to clean it up a bit. The extras include an essay and audio commentary by Michael F. Blake and a 1915 film, Alas and Alack, with Chaney in his pre-movie star days playing a hunchback.

The film is available at Flicker Alley’s website, where you can also pre-order their three upcoming releases: a set of all Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies (1916-17); the first volume of The Mack Sennett Collection, including 50 films; and We’re in the Movies, which collects some early local films made by itinerant moviemakers, as well as Steve Schaller’s 1983 documentary, When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, about the first film made in Wisconsin. There’s also a documentary about a small local theater in Los Angeles that showed silent films in the sound age.

D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation will celebrate its centennial next year, and now it’s also out on Blu-ray, from both Kino Classics in the USA and Eureka! in the UK. Both have the same new restoration from 35mm elements accompanied by the same score. The extras also appear to be identical–most notably seven Biograph shorts by Griffith about the Civil War. The main difference is that Kino throws in David Shepard’s 1993 restoration, with different musical accompaniment and a 24-minute documentary on the making of the film. Again, the Eureka! version is BD region B.

Last month Eureka! also released a BD of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951, BD region B) in their “Masters of Cinema” program. The release also contains a DVD version. You can check it out, along with other recent releases and upcoming ones here.

Edition-Filmmuseum

This German series works with an impressive array of archives, mostly German but also Swiss and Luxembourgian. The titles that result include modern films (Straub and Huillet figure in their catalogue, as does Werner Schroeter), television, experimental cinema (they’ve done several James Benning films), documentaries, and older films. (No Blu-ray as of now. Perhaps too expensive or perhaps just the sort of restraint that dictates the white backgrounds on their covers.)

Recently Edition-Filmmuseum released a set with two films by Gerhard Lamprecht, a little-known and but in the 1920s an important director of socially conscience films set among the working class. The two-disc release includes Menschen untereinander (1926) and Unter der Laterne (1928), each with two musical tracks to choose from. The German intertitles are subtitled in English and French, and the enclosed booklet is likewise trilingual. Like all the DVDs from this company, there is no region coding.

Similarly, another new release is devoted to the early films of Michail Kalatozov, a Georgian director better known for his Soviet films of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., The Cranes Are Flying and I Am Cuba). One of the films here is Salt for Svanetia (1930), one of those vaguely familiar but rare titles from the history books on Soviet montage cinema. The other is Nail in the Boot (1932).

Salt for Svanetia is indeed a classic that anyone interested in silent cinema and the Soviet Montage movement should see. Set in an extremely isolated, primitive area of the Caucasus, Svanetia obviously needs a dose of Soviet modernizing. The peasants can barely subsist, and a lack of salt makes their cows and goats unable to produce milk. It’s basically an attempt to combine an ethnographic documentary with large doses of Montage-style rapid editing, canted cameras, heroic framings of people against the sky. At one point a man cutting another’s hair is framed against one of the local feudal era towers in a low angle that makes it look like something out of Alexander Nevsky (above). The film is a fascinating peep into a little-known culture.

Kalatozov stages some sketchy scenes using the locals: an avalanche which kills some men, a resulting funeral, a woman giving birth alone in the countryside. There’s no over-arching plot, though, and the director wisely sticks with showing off local customs. Naturally at the end the Soviets are building a long road to reach the area, and there’s a promise of good things to come.

Nail in the Boot is impressive for about two-thirds of its length. It stages some large battle scenes between what I take to by the Red and White Armies during the Civil War. The Whites are attacking an armored train, and a lot of explosions result. The soldiers aboard the train fire machine-guns, and Kalatozov conveys the sound by alternating single-frame shots of the muzzle of the gun with single-frame shots of the man firing it. Sound familiar? It happens two or three more times in the course of this film. Both of these films are definitely part of the Montage movement, but the director has come along so late in it that he seems to feel all the good ideas have been used, and they’re worth using again. So we get another quotation from October in a canted shot of a cannon’s wheel, and Kalatozov even steals the idea of our hero looking and feeling very small and his prosecutor becoming a looming giant, as in Kozintsev and Trauberg’s The Overcoat:

We are some time into the film before we meet the hero, and I was thinking that this might be one of those Montage films with no single central figure. But well into it, the ammunition on the train is running out, and a messenger is sent to run and get help. Much of the film simply shows him running along, becoming increasingly lame as a bullet in his boot digs into his foot. Ultimately he does not reach his goal, though he tries hard. Once he is put on trial for treason, he blames the shoddy workmanship of the cobblers who made his boot badly. This seems a strange anti-climax after the exciting battle scenes earlier on, but the film actually turns out to be about Soviet workers paying attention to what they’re doing and not putting out a bad product. All the workers looking on at the trial look shame-faced at the hero’s accusation, suggesting that if a hundred percent of the workers are doing a bad job, there’s not much hope of rectifying the situation.

Both films are fascinating because they come so late in the Montage movement, which lasted from 1925 to 1933, and they are particularly valuable because it’s harder to see the films from this late period than those from the 1920s.

Both films have optional English subtitles.

By the way, Edition Filmmuseum also sells Flicker Alley films, and those in Europe and elsewhere might find them easier to order on its website.

You’re gonna need a bigger shelf

There are three notable new releases of French films. Before I get to the two epic, brick-like sets, let me mention the new Eureka! Blu-ray of Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont du Nord (1981) in the “Masters of Cinema” series. Admirably, the film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio. The supplements consist mainly of a thick booklet with some new essays, an interview with Rivette, and so on. You can read more about the booklet’s contents and buy the film here. Note that it is coded BD region B.

Now to the bricks.

At long last the French Impressionist director Jean Epstein is well represented on DVD. Although a few of his most famous films have appeared on video from time to time, these eight discs are a cornucopia of his work (plus a 68-minute documentary on his work by James June Schneider). They come from what are probably the best possible prints, since the set is issued by La Cinémathèque Française. Marie Epstein, who had made films herself in the late 1920s and 1930s, worked at the Cinémathèque for decades and helped preserve her brother’s work. A major retrospective of Epstein’s work ran at the Cinémathèque in April and May; the restorations in preparation for the series made possible to this DVD set. (This page links to further resources on Epstein.)

Epstein started out working for some of the large French film companies, though he mixed somewhat experimental films with more standard ones. His second surviving feature film, Cœur fidèle, is one of his most famous, and perhaps his masterpiece. A beautiful print of it is already available on a Eureka! DBD/BD combo (BD region B). There’s also a French DVD. I wrote a little about it when it made our top-ten films of 1923 list.

The big outer box of the set comes with three inner fold-out disc holders that reflect the phases of his career. The first is “Jean Epstein chez Albatros.” In 1924 Epstein joined the Russian-emigré company Albatros. Three of the four films he directed there are grouped together: Le Lion des Mogols (1924), starring Ivan Mosjoukine and Nathalie Lissenko; Le double amour (1925); and Les aventures de Robert Macaire (1925). The big gap here, and indeed in the entire set, is the absence of the fourth, L’Affiche (1924), which I think is one of his best. It does survive, so I hope it will eventually appear on disc. Apart from L’Affiche, these are all big-budget productions, and Robert Macaire is a serial running 200 minutes. This set has no overlap with the Albatros set from Flicker Alley that I wrote about last year and indeed is an excellent supplement to it.

Beginning in 1926, having been successful with his big Albatros films, Epstein produced his own work under the name “Les Film Jean Epstein.” Again, there were four films, the surviving three of which are on the discs in the second folder, “Jean Epstein: Première Vague”: Mauprat (1926), La glace à trois faces (1927), and La chute de la maison Usher (1928). (The lost film is Au pays de George Sand, 1926.) La chute de la maison Usher was for a long time the only Epstein film available on 16mm prints, which didn’t really do justice to its eerie German Expressionist-influenced sets.

Gradually, however, the reputation of La glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”) has grown, and it is another highlight of Epstein’s career. It introduced a trope of modernism into the cinema, the notion of using point of view to create ambiguity. The story shows scenes concerning one man as seen through the eyes of his three lovers–each, of course, making him seem a very different person.

The other films deserve discovery as well. Le Lion des Mogols has a clever story (written by Mosjoukine) which starts out in a fictional Tibetan city where the hero, a nobleman (Mosjoukine) incurs the sultan’s wrath and flees. A cut to a ship suddenly reveals that we are in a modern world, and the film becomes a fish-out-of-water story as the hero blunders onto the set of a movie location shoot on deck (above). Intrigued, the female star of the film helps him adjust and brings him in as a leading actor. Thus our hero jumps from one genre, the fantasy Far-Eastern melodrama (familiar from various German films of the time, including the Chinese sequence from Lang’s Der müde Tod) to a modern romance. The film has the advantage of scenes in and around Albatros’s own studio:

Les Film Jean Epstein produced some major work, but it didn’t make money, and in 1928 Epstein changed course, He made 28 more films, up until his death in 1953, most of which are virtually unknown. The exceptions are some films modest, lyrical films he shot in Breton. Seven of these are presented as “Jean Epstein: Poèmes Bretons”: Finis Terrae (1928, Epstein’s last silent film), Mor’vran (1930), Les Berceaux (1931) L’Or des mers (1933), Chanson d’Ar-mor (1935), Le tempestaire (1947), and Les feux de la mer (1948). These range from 6 minutes to 82 minutes long. Most have simple plots and involve the sea.

The set has been put together so that the supplements for each film are on the end of its disc, not lumped together on a separate disc. There is also a 158-page book, not booklet, with program notes and many images: posters, designs, publicity stills, and frames. (It also has the smallest page numbers I have ever seen.) I can find no indication that the set is region-coded, but the Amazon.fr page says it’s PAL region 2. (I cannot find any reference to the set on the Cinémathèque’s own site, so I can’t confirm either way.) It does have optional English subtitles.

Since the beginning of film history, France has produced one of the world’s great national cinemas, and Jacques Tati is one of its greatest directors. On Facebook, Ingrid Hoeben, one of Tati’s devoted fans, runs a page called “I’d like to be part of the Monsieur Hulot universe, if only as a cardboard cut-out”, and I think she speaks for many of us. (She also runs a FB page on PlayTime–as she spells it. Many writers use Playtime, and I prefer Play Time.)

For those who love Tati, there is finally a new set of his complete works, restored and available in separate DVD and Blu-ray sets. The imposing big black box contains seven discs, each in its own cardboard fold-over holder, one for each of the features and one for the shorts. There are extras on each disc. The small book included with the set has a brief bio of Tati, information on the restoration of the films, and program notes.

There are various versions of some Tati films. The Mon Oncle disc includes both the French and English-dubbed versions. The Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot disc has the 1953 version and the 1978 restoration. Jour de fête, which Tati tried to make in color, has three versions: the 1949 release print, the 1964 one with selective color added, and the 1994 restoration of the color version Tati had had to abandon.

The print of Play Time, though visually beautiful, is altered by some tampering by the restorers. It originally contained passages of music over a dark screen at beginning and end. I described these moments in my essay, “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception” (published in 1988 in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis). Of the beginning I wrote:

The film begins with pre-credits music involving percussion; at a seemingly arbitrary point in this music, the bright credits shot of clouds fades suddenly in from the darkness. Already we encounter the sound track as a separate level from the image track–as something to which we should pay cloe attention in its own right. (Unfortunately, most of this music seems to have been edited out of the re-release print.) (p. 253)

(The darkness and music actually last about 10 seconds before the cloud shot.)

And the ending, which in the original has several minutes of music played over a black screen:

Play Time structures even our transference, at the end, of aesthetic perception to everyday existence, by continuing its theme music for several minutes after the images stop–so long that we are forced to get up and move about to this music. The film’s sound track becomes an accompaniment for our own actions, inviting us to perceive our surroundings as we have perceived the film. (p. 261)

(The actual timing is about one minute, though it seems longer when you’re sitting in a darkened theater and are used to leaving immediately at film’s end.)

This new disc includes the dark footage at the end and the music, but the credits for the restoration and video are superimposed throughout–quite a different experience than music accompanying darkness. The music over darkness is shortened at the beginning to about 3 seconds, with the logo of Les Films de Mon Oncle’s logo and a dedication to Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s daughter.

All these superimposed credits alters Tati’s intentions considerably. He clearly meant for that concluding music to make us almost actors in his film and to carry over its defamiliarization of the fictional world into the real world. Without it, this cannot be considered the definitive version of Play Time. It may seem a small matter, but the original decision was completely reflected Tati’s distinctive style.

Fortunately the Criterion collection’s version retains the music over black at the end, as well as a different set of supplements. Completists will need to have both.

For many, Tati’s last feature, Parade, will be new. It’s not a M. Hulot film or even really a fiction film. It was made in Sweden and consists of a variety performance by musicians, singers, a magician, and so on, all MCed by Tati in propria persona. Between other acts, Tati performs some of his most famous pantomime bits, including a remarkable scene where, as a tennis player, he mimes part of the action as if caught by a slow-motion news camera. Tati also devised some little scenes to take place among the audience, which contains some of the same sort of cardboard cut-outs that first appeared in Play Time:

Parade was shot on video during live performances, but the acts were also staged in a studio in 35mm (see bottom). That’s the source of the inconsistent visual style, though it’s less apparent on video than when projected in 35mm on a large screen.

It’s a strange but enjoyable and even complex film, if one goes into it without expecting it to be like Tati’s others.

Very few will have seen all of Tati’s shorts. These fall into three periods.

Three of them are from the mid-1930s, brief comedies ranging from 16 to 24 minutes: On demande une brute, Gai Dimanche, and Soigne ton gauche. Tati was a young music-hall performer at the time, specializing in sports pantomimes.

Second, there is L’École des facteurs (1946), a 16-minute version of of the same story that he expanded into Jour de fête a few years later. L’École des facteurs was his directorial debut, the earlier shorts having been directed by others.

And third, Tati made some shorts late in his career: Cours du soir (directed by Nicolas Ribowski), Degustation maison, and Forza Bastia (the latter two directed by Tati’s daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, who used the original family name).

The set has optional English subtitles and is BD Region B.

On early Soviet cinema and much more

The title of Natascha Drubek’s new book, Russisches Licht: Von der Ikone zum frühen Sowjetischen Kino might seem to imply a narrow field of study. Actually, though, it ranges far, examining the introduction of electric lighting into Russia and examining what a wide range of Russian commentators wrote about light at the time. This includes, of course, the cinema, an art form both composed of light and using light during the filming.

The introductory section covers theoretical approaches to cinema, including the work of the Russian Formalists. Drubek goes on to consider factors in the early history of media in Russian and Soviet cinema, including writings on theaters and film censorship.

She then goes back to the roots of thought on light and media further back in Russian history, dealing with icons and the church, as well as the influence of icons on the Russian avant-garde of the pre-Revolutionary period. Finally she deals with cinema and in particular with the films of Evgenii Bauer.

I cannot claim to have read the book, for with my shaky knowledge of German it would be slow going. But it is an impressive achievement, and anyone interested in Russian/Soviet cinema and especially Bauer should have it. It is available online directly from the publisher.

Tati’s classic fishing routine in Parade.