12 hours, Ritrovato time

Monday | June 30, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Reporting on the magnificent Cinema Ritrovato festival at Bologna has become a tradition with us, but it’s become harder to find time during the event to write an entry. The program has swollen to 600 titles over eight days, and attendance has shot up as well; the figure we heard was over 2000 souls. The organizers–Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée–have responded to requests for more repetition of titles by slotting shows in the evening, some starting as late as 9:45. (You can scan the daily program here.) There are as well panel discussions, meetings with authors, and some unique events, such as carbon-arc outdoor shows, the traditional screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, and Peter Kubelka’s massive and mysterious Monument Film. Add in time to browse the vast book and DVD sales tables, and the need to socialize with old friends.

In all, Ritrovato is becoming the Cannes of classic cinema: diverse, turbulent, and overwhelming. How best to give you a sense of the tidal-wave energy of the event? I’ve decided to take off one morning and write up just one day, Monday 29 June. I don’t know when Kristin and I will find time to write another entry, for reasons you will discover.

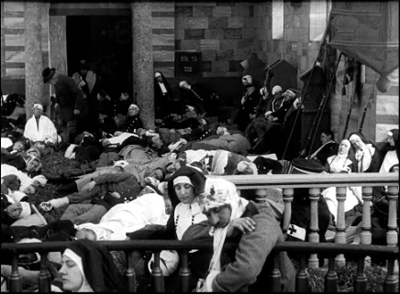

9:00 AM: Ned Med Vaabnene! (Lay Down Your Arms!, 1914) was a big Danish production, based on a popular anti-war novel by the German Bertha von Suttner. It’s a remnant of the days when the rich went to war along with the common folk. (Sounds quaint in today’s America, where the elite have other priorities.) The Nordisk studio specialized in “nobility films,” melodramas that show the upper class brought low by circumstances; Dreyer’s The President (1919) is another example. The film, directed by Holger-Madsen, shows a family devastated by war and its aftermath. It’s shot in tableau style, with the restrained acting and sumptuous, light-filled sets characteristic of Nordisk. The combat scenes are remarkably forceful, but the most harrowing scene, for me, is the shot showing a battlefront hospital, with exhausted nuns and wounded men strewn around the shot–a tangle of limbs and heads.

Premiered soon after the Great War broke out, Lay Down Your Arms! anticipates Nordisk’s wartime policy. Denmark was a neutral country, and the Danish industry depended on both the German and the American markets. As a result, most of the films studiously avoided taking sides. After the war, with the revival of the German industry and the circulation of American films in Europe, Nordisk lost its powerful position in the international market.

The entire film is available for viewing online at the Danish Film Institute site.

Programmer Mariann Lewinsky, in charge of the “100 Years Ago” thread, wisely included other pacifist films from the mid-teens. One of the high points was the evening screening, on the Piazza Maggiore, of the fine Belgian film Maudite soit la guerre (1914), in the hand-colored version I discussed some years back. Not by accident, I suspect, Lay Down Your Arms! featured several Lewinsky dogs.

10:30 AM: Werner Hochbaum was an unknown name to me, but after seeing Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow, 1933), I realized that was my loss. This story of a cafe violinist released from prison is a sort of anthology of 1920s International Style devices: canted angles, rapid montages, City Symphony passages, flamboyant camera movements, multiple-image superimpositions, and huge close-ups of faces, hands, and objects. The work on sound is no less ambitious, with voice-overs, sound motifs (a carousel, a canary’s call-and-response to a chiming doorbell), offscreen dialogue, and harsh auditory montages of traffic and city life. Everything from Impressionist subjective-focus point-of-view to Expressionist shadow work comes into play.

The plot is gripping throughout. At first we don’t know why the violinist was imprisoned, and we learn about the case first from his gossiping neighbors (excellent run of whispers during fast-cut close-ups of housewives), then from his own flashbacks, which build up to a revelation of the murder he committed. Threaded with all this is another uncertainty: Has his wife begun a love affair while he was in jail? Giving us only glimpses of her life as a cafe waitress, Hochbaum leads us to suspect that he will come home to more misery–and perhaps another temptation to murder.

Along with all this were arresting side scenes of cafe life, like a fat woman ordering up a gigolo to dance with her, reminiscent of Georg Grosz and the New Objectivity’s cynical portrait of daily desperation. It’s a lot to pack into 73 minutes, but Morgen beginnt das Leben succeeds smoothly and made me want more. Alex Horwath‘s introduction confirmed that this is a director we should know better. We can hope that a DVD edition is coming soon.

Noon: A packed house for the panel of three American studio archivists: Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox, Grover Crisp of Sony, and Ned Price of Warners. Too many ideas to summarize here, but one that emerged: Digital tools are great for restoration, not so reliable for preservation.

Ned (left) emphasized that now scanners are very sensitive to the oldest negatives, with their shrinkage and warpage. But Ned pointed out that today’s monitors don’t often render the full color scale needed to respect film’s tonal range, so that weak monitors mean that we are “working blind” and may “bake in” flaws that will be evident when display devices improve. Likewise, low bit-depths (often only 10-bit) in outputting to film for preservation can cause problems later. Grain reduction is another big problem. Grover (center) added: “When you do anything to grain, you’re denaturing the film.”

On the restoration front, Schawn showed clips from the 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth, first from a beautiful photochemical restoration of twelve years ago, then from a recent digital one. To my eye, the warm skin tones of the 35mm image were more attractive than the almost porcelain surfaces of the digital version, but the latter was sharper and contained a healthy amount of grain. Grover screened A/B comparisons of the main titles of Only Angels Have Wings and Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa (Sandra ), both of which showed how handily digital restoration creates a rock-stable image, without the jitter and weave unavoidable with a strip of film.

All the panelists agreed that digital restorations are rapidly improving; ones finished only a few years ago could now be done better. A major problem coming up is that younger restoration workers know the digital tools better than the look and feel of photochemical, particularly the surface of older films. Grover recalled that one eager techie added flicker to a Capra silent because he thought that was how old movies looked.

1:15 PM: Hurried lunch with Schawn. Main topic: The Grand Budapest Hotel, but also the vagaries of the DVD and Blu-Ray market.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

You Never Know Women (1926) is an exercise in good old classical storytelling. The plot presents Vera (Florence Vidor), star of a troupe of Russian entertainers, momentarily entranced by a no-good millionaire who wants to seduce her. The magician of the troupe, Norodin (Clive Brook) loves her, but she’s unaware of her feelings for him until the Lothario’s true nature is exposed. El Brendel adds spice as a clown devoted to his pet duck.

Variety‘s review was ecstatic, claiming that “Wellman at the megaphone lifts himself into the ranks of select directors with by his handling of this story, for his direction is never obvious or old-fashioned.” I’ll say. Filled with running gags, seesawing conflicts, and motifs (Ivan’s skill at knife-throwing, the expletive, “Ridiculous!”), You Never Know Women has a headlong pace. With nearly a thousand shots in 70 minutes, it relies on glances, gestures, and reactions to channel the dramatic flow. It needs only three expository titles, letting its 100 or so dialogue titles pinpoint key emotional transitions. In anticipating the sound cinema that was just around the corner, You Never Know Women resembles the more famous Beggars of Life (1928, given pride of place at Ritrovato), which as I recall uses dialogue titles exclusively.

The Man I Love (1929) tells the familiar story of a prizefighter who, as he rises in the game, leaves his loyal woman behind. As an early sound film, it relies on multiple-camera shooting for extended dialogue scenes, but Wellman enlivens the staging with unusual angles, including a view of a quarrel seen through a window in a dressing-room door. The Man I Love boasts the sort of ambitious, somewhat bumpy tracking shots we sometimes find in early talkies. One swaggering camera movement takes us from the locker room into an arena, down the aisle, past the ring, and to Dum Dum’s anxious wife in the crowd, a sketchy prefiguration of the celebrated Steadicam movement in Raging Bull. The fight scenes, not requiring sync sound, are shot with brio, while the dialogue scenes are extremely well-miked, allowing for fairly fast line readings and varied volume and emphasis in the voices.

Gina Teraroli and David Phelps, along with other colleagues, have assembled a wide-ranging dossier on Wellman’s work that serves as a fine complement to the Ritrovato thread.

5-something PM: One of the things in the first edition of our Film History: An Introduction that made me proud was the inclusion of sections on Indian cinema, a subject usually ignored in textbook surveys. I remember in the late 1980s and early 1990s watching the 1950s-1960s classics of Hindi filmmaking with a sense of discovery: How could we not have known this invigorating tradition? It was therefore with a sense of homecoming that I visited Raj Kapoor’s Awara (“The Vagabond,” 1951), in a pretty sepia-tinted print.

The young ne’er-do-well Raj (no last name, and this is important) is on trial for attacking a judge in his home. A female lawyer, Rita, takes up his defense and urges the judge, on the witness stand, to tell why he expelled his wife from his home many years ago. The wife had been kidnapped by the gangster Jagga, and the judge assumed that the child she was now expecting was Jagga’s. Before the courtroom, Rita recounts up the story of how young Raj, actually the judge’s legitimate son, took up a life of crime. To add spice, Rita is the judge’s ward and Raj’s lover.

No coincidence, no story, they say, and Awara offers plenty of timely misunderstandings and improbably neat encounters. No matter. We’re told that TV narrative, by stretching its tale over several hours, can introduce novelistic breadth, but so can Indian classics of the 1950s. This one takes us across twenty-four years and as many ups and downs as a mini-series might offer. Not to mention Kapoor’s vigorous visual style, with huge sets, vivacious fantasy sequences, and traces of 1940s Hollywood hysteria (chiaroscuro, fluid track-ins to overwrought faces, even thunder and lightning in the distance). Here Raj, about to stab the judge, shatters the childhood picture of Rita; her simple gaze checks his moment of revenge.

Then there are the songs, lusciously sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Mukesh. Of course the sprightly “Awara Hoon” is the official classic and Kapoor’s signature tune, but this time around my favorite was the duet, “I wish the moon…,” with Rita asking the moon to look away and Raj asking it to turn to him. With its glamorized social realism, its tale of a good boy gone wrong, unjustly punished, and eventually redeemed, and its primal themes of mothers, fathers, and sons, Awara is a milestone in the world’s popular cinema…. and just one of several Indian classics in this year’s Ritrovato.

That was one day. Now I’m off to…what? Polish films in widescreen? The Riccardo Freda retrospective? The rare Ojo Okichi? Or maybe the restored Oklahoma!? In any case, this afternoon an incontro on Nicola Mazzanti‘s book 75000 films, and tonight Guru Dutt’s glorious Pyaasa.

I tell you, it’s hard to keep up, running on Ritrovato time.

Nargis and Raj Kapoor sing to the moon in Awara.