Il Cinema Ritrovato: Strands from the 1950s and 1960s

Saturday | July 12, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

Faraon (1966).

Kristin here:

David has already posted an early report on his first full day at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. It conveys something of the overwhelming abundance of offerings at this year’s festival. Writing another entry during the festival itself proved impossible, given our packed schedules, but now we have time to catch our breath and reflect on what we were able to see.

As with the 2013 festival, I decided that the only way to navigate the many simultaneous screenings was to pick out some major threads and stick with them. I chose the retrospective of Polish widescreen films of the 1960s, that of Indian classics from the 1950s, and the third season of early Japanese talkies. Miraculously, none of these conflicted with each other, the Polish films being on mainly in the mornings, the Japanese ones directly after the lunch break, and the Indian films starting late in the afternoon.

Again, it was possible to fit in a few films from the other programs on offer, including a series of Germaine Dulac’s films, restorations of East of Eden and Rebel without a Cause, a selection of Riccardo Freda’s work, Italian contributions lifted from various anthology films of the 1950s and 1960s, a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Österreichisches Filmmuseum, and many Chaplin shorts (the festival was preceded by a brief conference on Chaplin).

The annual Cento Anni Fa program, showing films from 100 years ago, has changed, in part to accommodate the fact that the transition to feature films was well underway. The series programer, Mariann Lewinsky, has also branched out. Having discovered many unknown or little-known early silents during her annual quests, she has included other brief thematic programs, such as fashion in early films. In addition, there was a lengthier selection of early films dealing with war, given that we are now in the centenary of World War I.

A Journey from Pole to Pole

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965).

To me the biggest revelation of the festival was the program of Polish anamorphic widescreen films. Representing most of the major Polish directors working in widescreen in the 1960s, these were shown in 35mm, mostly in original release prints from the period, on the big screen of the Cinema Arlecchino theatre. Despite occasional wear in the prints, they looked great.

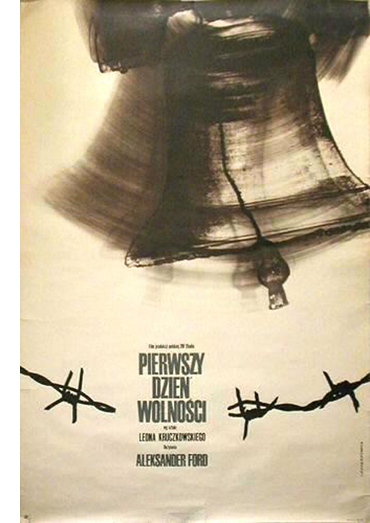

The series kicked off with Aleksander Ford’s little-known The First Day of Freedom (Perwszy dzień wolności, 1964). Like many of the films in the program, it dealt with World War II. Polish soldiers, escaped from a POW camp, enter a nearly deserted German town. They disagree on whether to help protect the civilians they encounter or participate in the general rape and pillage in the wake of the Nazi retreat. It’s a grim and realistic look at a topic seldom tackled in films about the war.

Also on the program was Andrej Munk’s Passenger (Paseżerka, 1963), left unfinished when the director was killed in a car accident. His colleagues eventually decided to assemble the film without additional footage, drawing upon still photos for some scenes and an effective voiceover filling in the action. The effort works well, and the result is a powerful examination of a Nazi death camp. The story does not concentrate on Jews but on political prisoners, implicitly communists and other rebels. The result is the sort of disguised political comment on Poland’s contemporary situation that is common in these films.

Early on, a middle-aged woman aboard a ship tells her companion about her life in as an official in the camp–a story that is contradicted when the actual scenes of her activities at the camp play out. The woman singles out a female prisoner, Marta, and rationalizes her irrational mixture of rewards and punishments as efforts to save her from the other prisoners’ fates. With its depictions of cat-and-mouse games between prisoners and captors and its references to mysterious sadistic rituals played out by the guards, the film is a powerful meditation on the camps, worthy, as Peter von Bagh’s program notes say, to sit alongside Resnais’s documentary, Night and Fog.

Among the unexpected delights of the series was Lenin in Poland (Lenin w Polsce, 1966) by Sergei Yutkevich (or, as he is credited here, Jutkevič). Yutkevich began as a member of the Soviet Montage movement, contributing a little-known, late feature, Golden Mountains (1932). Working in Poland, he managed the formidable task of humanizing Lenin in unorthodox ways. Yutkevich concentrates on the leader’s Polish exile on the eve of World War I. Framed by Lenin’s brief imprisonment on charges of espionage, the film proceeds through flashbacks to his recent activities. As portrayed by Maksim Strauch, whose resemblance to the revolutionary leader gave him a long career in numerous films, Lenin is humorous, kind, thoughtful, and a likeable protagonist. Yutkevich includes touches from the Montage movement, with some passages of quick cutting and frequent heroic framings of the protagonist.

With my interest in ancient Egypt, I was particularly curious about Faraon (Pharaoh, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1966). The director tackles the unusual and obscure topic of the end of the 20th Dynasty, which led to the end of the golden age of the New Kingdom and the instability of the Third Intermediate Period. The film’s drama comes from the real-life conflict between the impoverished, weakened monarch and the wealthy, powerful priests of Amun in Thebes. I’m not sure how well an audience not familiar with this era would follow the plot, even simplified as it is. There are some remarkable crowd scenes, as at the top of this entry, when Herhor, the chief of the priests, rallies the crowd against the pharaoh. Still, I did not find the story engaging. Presumably it was a covert commentary on politics in Poland at the time.

The best-known of Polish directors, Andrzej Wajda, was represented by two films. One was the earliest film shown in the series, Samson, from 1961. It concerns a young Jewish man who is lured to escape from the Warsaw Ghetto and spends most of the film dodging the police by moving from one temporary haven to another. Wajda creates a compelling depiction of the ghetto early on, and I wished he had stayed in that environment longer.

My favorite film of the festival was Wajda’s little-known Ashes (Popioły [not to be confused with Ashes and Diamonds], 1965), an epic tale of the Napoleonic wars and Poland’s unwise participation in them on the side of the French. The protagonist, Rafal Olbromski, is a naive young nobleman from a rural area, a Candide-like figure whom we follow as he leaves his estate to go to war and moves from locale to locale, manipulated by more sophisticated characters. The result is a dizzying succession of battle scenes, largely without any context being established, punctuated by visits to the estates of those who are backing the Polish participation in Napoleon’s conquests. Wajda seemed to have had nearly limitless funds for the film, and the battle scenes are monumental.

Far less obscure is Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (Rękopis znaleziony a Saragossie, 1965), a cult item among film buffs and reputedly one of Luis Buñuel’s favorite films. It’s a complex, surreal tale of a wandering soldier of the 18th Century who passes the gibbets of two executed men in a bleak Spanish landscape and enters a mysterious inn. There he encounters a large bound manuscript that leads him into a world of shifting fantasy and tales within tales within tales. Has’s was certainly one of the most humorous and entertaining films in the series.

The latest film in the program, Adventure with a Song (Przygoda z piosenka, Stanisław Bareja, 1969), was radically different from the others and provided a look at popular Polish cinema of the 1960s. Bareja was a successful director of comedies and musicals. This one follows a young singer who wins a local singing contest with the improbably named “The Donkey Had Two Troughs,” and decides to head for a professional career in Paris. The filmmakers’ attempts to replicate the Mod styles and garish colors of the 1960s in the West yield an incongruous and awkward but fascinating film .

The one disadvantage of seeing these vintage distribution prints (mostly with English subtitles) was that some were abridged versions, occasionally radically so. Samson, The First Days of Freedom, Adventure with a Song, and, inevitably Passenger were shown complete. Judging by imdb’s timings, however, others were missing significant amounts footage: Ashes (shown at 169′, originally 234′), The Saragossa Manuscript (155′ vs. 175′), Pharaoh (149′ vs. 180′).

Recently there seems to be a revival of interest in Polish classic films. Martin Scorsese has curated a large program that is currently touring the US with digital copies of restored films. (For links to numerous articles on the series and the restorations, see its Facebook page.) I hope that some enterprising company will issue the complete versions of these Polish classics in their proper widescreen ratios. Ashes is a particularly good candidate for such treatment. Having sat through it once at nearly three hours, I would happily watch it at closer to four.

Worthy of restoration

There’s a growing interest in recent Indian films, at least in the USA. Our biggest local multiplex nearly always devotes  one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

One reason is because many of these classics still await restoration. While most programs shown in Bologna consist of newly restored prints, this series was titled “The Golden 50s: India’s Endangered Classics.” Each of the features was accompanied by an episode of “Indian News Review,” a newsreel that for years was shown in film programs across India. Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder of the Film Heritage Foundation, curated the series and introduced each film, emphasizing that even the eight classics selected for the program are in danger if not properly restored soon.

The need was evident from the prints. Some were old distribution prints, but three of the films could only be shown on Blu-ray. Even under these conditions, however, the range and quality of Indian cinema of the 1950s was apparent.

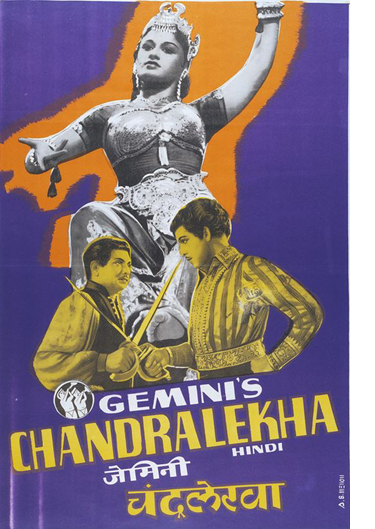

The earliest film in the series, Chandralekha (S. S. Vasan), was made a little before that decade, in 1948. Its presence stems from its crucial importance in Indian film history. It was the first big, successful Indian musical of the post-colonial era and set the pattern for many of the country’s subsequent films. The story has a fairy-tale setting, with a good and an evil brother fighting over the throne of their father’s kingdom and also for the hand of the beautiful Chandralekha. The rambling plot includes lots of songs and dance numbers, leading up to the climactic, legendary Drum Dance (below right), with dozens of dancers atop rows of enormous drums. It lives up to expectations. (For more on Chandralekha, see fellow Ritrovato fan Antii Alanen’s epic blog post.)

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

One of the great Indian directors, Ritwik Ghatak, has become somewhat familiar in the West, thanks in part to the British Film Institute’s issuing two of his masterpieces on DVD: A River Called Titas and The Cloud-Capped Star. The series at Bologna included Ghatak’s first feature, Ajantrik (1957). It is set among the poverty-stricken Oraons, an isolated population in Central India, and follows a man who is devoted to his dilapidated taxi, which he manages to hold together well enough to supply him a marginal living. He has come to think of the car as a human companion. (Accordingly, the title means, roughly, “not mechanical,” although for western distribution it was given the unenticing title Pathetic Fallacy.) Though Ajantrik is not a major film on the level of the others in the program, it was good to have the rare opportunity to see Ghatak’s first film.

The star of the series was undoubtedly an equally respected director, Guru Dutt. Two of his films, in both of which he also starred, were shown. One of his finest films, Pyaasa (The Thirsty One, 1957), was perhaps the best film of the program. Dutt is considered to have integrated the conventional song episodes of Indian cinema into his films more skillfully and in more original ways than other directors.

Dutt plays a great but unappreciated poet whose work is ignored by the intelligentsia of his own class. He wanders in despair among the poor and outcast, for whom he has great sympathy. In one haunting scene, he walks through a brothel district and sings of his despair for humanity (below). Early in the film he meets a prostitute who appreciates his poetry and falls in love with him. Only after the poet’s apparent death does his work become widely loved among the the common people, but his reputation is exploited by his hypocritical family and publisher.

Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959), was also shown. Again Dutt plays an unappreciated artist. A film director divorces his wife and becomes the target of gossip when he casts a beautiful young actress in his next movie. His personal misery affects his ability to direct, and after a slow slide into alcoholism, he loses his job. The plot allows Dutt to express self-pity more obviously than in Pyaasa, and the comic scenes with his ex-wife’s family strike an odd tone in such a grim story. Kaagaz Ke Phool was not a success, and Dutt gave up filmmaking altogether, dying of an overdose of sleeping pills five years later. As Dungparapur pointed out, he was one of several important Indian filmmakers who died rather young, which makes the rescue of these classics all the more essential.

Pyaasa (1957).