What-if movies: Forking paths in the drawing room

Sunday | November 23, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

Dangerous Corner (1934).

DB here:

We habitually indulge in what-if thinking. What if you hadn’t gone to that particular school, met those specific friends, lived in that particular place? Your future would have been very different, in ways you sometimes speculate about. Here is Brian Eno explaining how he found his career:

As a result of going into a subway station and meeting Andy [Mackay], I joined Roxy Music, and as a result of that I have a career in music I wouldn’t have had otherwise. If I’d walked ten yards further on the platform or missed that train or been in the next carriage, I probably would have been an art teacher now.

We think this way on a small time-scale too. If you had left that damned parking lot a little earlier, you wouldn’t have had the fender-bender you had down the street.

Just as flashbacks exploit our common-sense intuitions about memory, other narrative strategies tap our habit of what-if thinking. Some movies evoke alternative but parallel fictional worlds. The most recent what-if movie I know is Edge of Tomorrow, whose tagline and video release title, Live Die Repeat, sums up its premise. I thought it was an ingenious use of the format, although the ending left me puzzled. Earlier on this site I wrote about a more intriguing example, Duncan Jones’s Source Code. Sometimes I call these “multiple-draft” plots because they keep revising the action until it comes out right.

Hong Sangsoo has explored the what-if possibility with unusual energy, but he’s less explicit about setting up the structure than Hollywood films are. With his movies, sometimes you don’t realize you’re in a parallel-world plot until you notice repetitions of action with tiny differences. (We have entries on Hong here and here and here.)

Some years back I wrote an essay, “Film Futures,” in which I analyzed the what-if, or “forking-path” narrative. That essay, revised for the book Poetics of Cinema, is now available on this site. It explores several examples: Kieślowski’s Blind Chance, Tykwer’s Run Lola Run, Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be Number One, and Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors.

One Hollywood experiment in this vein was a film version of J. B. Priestley’s 1932 play, Dangerous Corner. I mentioned the play in the essay, but I wasn’t then aware that a film version had been made by RKO in 1934. (To add an extra sting to my ego, it was sitting in our massive collection of RKO movies on campus.) I learned of it just recently when it aired on Turner Classic Movies, a national treasure I have celebrated before. The film quickly showed up online at Rarefilmm, and probably elsewhere.

In the essay, my approach was to treat these films as a sort of genre. What conventions rule them? What motivates the forking-path format—a science-fiction device such as a time machine, or fortunetelling, or something else? How do they tap our what-if thinking? Dangerous Corner lets me test my proposal on a new instance and offer a trailer for a new online essay.

As with any comprehensive narrative analysis, there are spoilers.

They have been here before

Darkness. We hear a gunshot and a woman’s scream. The stage lights come up and reveal some women in a drawing room listening to a radio play, “The Sleeping Dog.” Soon they’re joined by their male partners. An inadvertent remark by one of the women starts a cascade of confessions. The couples reveal a seething mass of illicit affairs, drug addiction, and repressed sexual desires.

As a result of the frenzy of truth-telling, the husband who set the process in motion lurches offstage and shoots himself. Darkness descends; a woman’s scream. When the lights come up, we are back in the drawing room. The broadcast play is at the same point as before. This time things go differently, and music from the radio fills the room as the couples enjoy a banal evening.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

In the course of evening number one, all sorts of naughtiness are revealed. Martin, much loved by all, is revealed to have been a thrill-seeking drug addict with whom Robert’s wife Freda has been having an affair. Olwen is secretly in love with Robert. Gordon’s wife Betty is Charles’s mistress. Gordon in turn is in love with Martin, and we’re to understand they’ve had an intermittent gay affair. Martin has died not by suicide but by accident, when Olwen was struggling to escape from his attempt to rape her. In all, the three publishers’ private lives would suffice for a steamy best-seller.

The point of Priestley’s play is that revealing the truth is a risky business, like driving around a dangerous corner. He uses the forking-path format to suggest the harm of revealing things best kept hidden. Hence the radio play’s title, a reference to letting sleeping dogs lie. For Priestley, however, the parallel-worlds conceit was more than an artistic device. He insisted that Dangerous Corner not be regarded as a dream play but rather “a What Might Have Been.” It proceeded from Priestley’s deep interest in time, which he saw as not merely the linear, “once-and-for-all” track of daily life.

Our real selves are the whole stretches of our lives, and . . . at any given moment during those lives we are merely taking a three-dimensional cross-section of a four-, or multi-dimensional reality.

The same interest in time as split or looped is seen in his 1937 plays Time and the Conways and I Have Been Here Before.

The film version of Dangerous Corner makes some important changes. As you’d expect for a film of the 1930s, the gay plotline and the drug addiction are excised. The character of Charles (Melvyn Douglas) is made more virtuous. He is revealed as the thief, as in the original, but here he has stolen the bonds to help Betty pay off gambling debts. She is no longer his mistress but a friend he is protecting. In addition, Charles is shown pursuing Ann (the play’s Olwen), who turns aside his proposals of marriage. At the end of the film, she agrees to marry him, providing a romantic wrapup.

The first seventeen minutes of the film establish the Charles-Ann courtship and present portions of the play’s backstory. We witness the three men discovering the theft of the bonds, and soon we watch Charles’ discovery of the dead Martin. An inquest declares the death a suicide, and a year passes. Now begins the play’s opening situation, with the women in the parlor. But there’s no longer a radio play running; instead, they’re listening to music before they hear a gunshot. That turns out to be the result of Robert’s firing his pistol into the garden to show it off to Gordon and Charles.

Coming into the drawing room, the men pair up with the woman and banter with their guest, the novelist Maude Mockridge. (She’s in the play as well.) The radio becomes important when Gordon goes to it to tune in some dance music, but the tube fails and, as he puts it, “I guess we’ll have to talk.” From then on the film follows the general contours of the play, and I think it exemplifies the conventions of forking-path plots pretty well. What are those conventions?

Using the correct fork

In the essay I start by suggesting that the action in forking-path plots is understood to be linear. Within each track, there is a smooth progression of cause and effect. Both play and film obey this condition through the simple chronology of scenes, but it’s also controlling the puzzle of the missing bonds, which is eventually explained by detective-story logic. Charles admits to taking them, and in the film Betty further explains that he did it to cover the gambling debts she wouldn’t confess to Gordon.

Linearity is also reinforced by a simple either-or switch. In the film’s tell-all version, Gordon can’t play dance music on the radio because there isn’t a spare tube for the radio set. Then begin the exposures of all the peccadilloes. In the alternate-reality version, there is a spare tube in the drawer, and so the exposures can be averted. Tube there: certain things follow. Tube not there: other things follow. Each chain of events proceeds without break or further splitting.

The radio tube is part of the film’s use of a second principle, what my essay calls signposting. If we’re to understand that there are alternative plotlines, we need some clear markings. In the film, we get several.

First there is the “reset” moment in the second version, when we return to the women moving to the French windows and hearing Robert’s firing of the pistol into the garden. That is a pure replay. What follows reiterates the action we saw earlier: The men joining the women, the radio announcing the time, and the initial chat before the signal fails and Gordon looks for—and this time, finds—a fresh radio tube. He thoughtfully reiterates the split for us. Dancing with Betty, Gordon says: “If Freda hadn’t had that spare radio tube, there wouldn’t have been any dance music, and then—well, anything might have happened.” As I suggest in the essay, characters in forking-path plots often get quite explicit about the what-if premise.

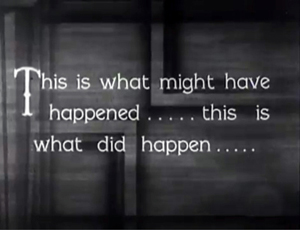

More unusual is the film’s use of intertitles as signposts. Robert, overcome with despair by the results of his relentless demand that everyone confess, runs to his room and shoots himself. The screen goes dark, with traces of smoke. Then we get this title:

At face value, this intertitle says that the stretch of time in which the characters exposed their private lives (the first “This”) is fictitious, while the amicable, truth-concealing version we’re about to see (the second “This”) is veridical.

Is this a bit of hand-holding for an audience that wasn’t prepared for the forking-path device? It does have that function, and to our taste it’s probably too explicit signposting. But it’s more interesting than it appears, because it reverses an intertitle that appears in the film’s opening.

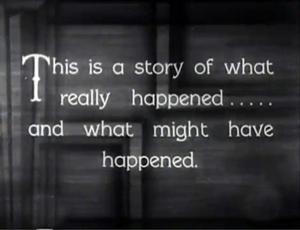

Before the action starts, we get this expository title.

Even without knowing how the film will develop, we are invited to imagine a two-part structure. After seeing the whole film, we can see that this puts the dual worlds on the same footing. The phrasing could be suggesting that the cascade of admissions we’ll see is what really happened, while the smooth social veneering of the final scenes was only an alternative possibility. At the climax, we’ll see the second title as a revision of this slightly puzzling one, which now might seem a bit of playful misleading.

But I think this first title is ambiguous in an intriguing way. The film really has three parts. First there are the 1933 events outside the drawing room, involving the robbery and Martin’s apparent suicide; these scenes aren’t in the play. Next block is the first, confessional versions of the 1934 evening. The third part is the alternative, calm version of the 1934 evening. From this angle, the first title is telling us that the 1933 section leading up to the crucial evening is “what really happened,” and that is indeed the case. We don’t get alternative versions of the robbery or Martin’s death. Accordingly, the sordid first iteration of the evening, the film’s second part, becomes “what might have happened.” In a weird way, the title is accurate about the first two chunks of the plot.

In other words, I’m suggesting that the titles fit the film’s structure as follows. The first title is in red, the second in green.

“This is a story of what really happened…”: The 1933 section.

“…and what might have happened.”/“This is what might have happened…”: First, scandalous version of 1934 evening events.

“…this is what did happen.”: Second, banal version of 1934 evening events.

Anyhow, two versions of the evening are quite enough for us. We can imagine more, but in films we never really encounter the radical plurality of multiple worlds. The physics of a true multiverse would offer indefinitely many variants, including ones in which any particular person doesn’t exist. In some worlds, Gordon would be married to Ann, Robert would court Betty, Charles would be a terrier, and so on. But—and here’s my third principle of such storytelling—the usual forking-path plot revisits essentially the same story world with the same characters, relationships, and settings, and most of the same actions. I call it the principle of intersection.

Intersection assures that we don’t get overwhelmed by having to meet a raft of new characters, figure out new settings or time periods, and generally reorient ourselves with each path we’re led down. Forking-path plots, from A Christmas Carol to It’s a Wonderful Life, keep things simple for us by changing very a few features of their rival worlds. Despite Priestley’s belief that each instant of our lives opens up many alternatives, that gigantic exfoliation of actions is very hard to dramatize and even harder for us to keep track of. So in both play and film, we have the same small world, with only a few differences. That works to the plot’s advantage, because those small differences—the radio works/ it doesn’t work, the cigarette box attracts attention/ it doesn’t—can be given enormous importance.

More rules

A fourth principle of forking-path plots involves the use of cohesion devices—elements of story or narration that smoothly link scenes. Cohesion devices are mid-sized examples of Hollywood’s love of continuity on every scale: cause and effect across the whole plot, foreshadowing of a later scene by an earlier one, hooks between sequences, and at the finest grain, shot-to-shot matching. Accordingly, each path in a forking plot ought to lead us along as easily as a normal plot would.

The essay mentions appointments and deadlines as common cohesion tactics. These aren’t very prominent in either the play or the film version of Dangerous Corner, chiefly because the forked action takes place in such a limited time span. But other devices, such as dissolves and fades, help the parts stick together. In the film a flashback dramatizes what Ann says took place on the night of Martin’s death in a way that fits tidily into the overall arc of the plot.

More interesting in the film are the parallels, a common byproduct of forking-path construction. At a macro-level, the two or three or however many paths are sensed as equivalent, variant versions that the viewer is invited to liken or contrast. And both our play and film reiterate the parallels among the couples; the visiting novelist Maude Mockridge says in the film that Charles and Ann should marry and complete the perfect symmetry set up by the “snug” pairings of the two other couples.

In the course of the first night’s exposures, hidden parallels are brought to light. Ann is mutely in love with Robert, who is mutely in love with Betty. Both the Freda-Robert marriage and the Gordon-Betty one are revealed as loveless. In the play, more parallels are piled on: Both Freda and Gordon have Martin for a lover, while Charles keeps Betty as his mistress.

Since parallels invite us to note contrasts, we can see that Phil Rosen (never accorded the status of an auteur) has somewhat altered things during the replay portion of the climax. Some variations in framing mark the second version as different from the first.

Mostly the purpose of the new angles in the replay is to highlight Charles and Ann, preparing us for their romantic alliance on the patio. The first version makes them small and far off-center left; the second emphasizes them much more, with the high angle enlarging and centering their flirtatious encounter.

My two last principles are also borne out in the film version of Dangerous Corner. One says that the last path traced presupposes the others. By that I mean it can take the earlier iterations as already read.

One result is that later versions of events can presented more briefly. When an alternative reality runs through bits we’ve already seen, we don’t need to see the full original version. This happens in the second fork of the film, which takes less than three minutes to get us to the crucial split—when Gordon discovers the fresh radio tube and tunes in the dance music. The first iteration of the evening’s events took almost five minutes to get us to the same point. This may seem a minor difference, but such intervals matter in a movie whose action consumes only sixty-two minutes on the screen.

Moreover, one time-saving passage shows the importance of the first iteration as setting up the situation. In the first version, Maude the novelist inquires about Martin, and she bends over a portrait photo of him.

This shot is less for her than for us, introducing the character whom we’ll see in Ann’s flashback. During the second version, we don’t get the full discussion between Maude and Freda, and we aren’t shown the photo. The narration assumes that after the flashback Martin is vivid enough in our memory. What replaces the insert of Martin is a reverse shot of Freda, describing Martin.

Now that we know she was Martin’s mistress, we’re in a position to appreciate how her dialogue and expressions conceal their relationship.

Similarly, the first version stresses the cigarette box that Ann inadvertently says she recognizes. The second version contents itself with a long shot, because now no one will question her about it.

The sense that the last path we see presumes the others has a more interesting side effect. Sometimes we get the sense that in the last go-round the character is mysteriously aware of the other paths she or he has taken. This happens in Sliding Doors and Run Lola Run, when each heroine seems to have learned from her experiences in the parallel worlds. And multiple-draft films like Groundhog Day and Edge of Tomorrow make this learning process essential to the action. The premise is illogical, but narratives often violate logic.

Something similar happens in the film (but not the play) of Dangerous Corner. Alone with Charles on the patio, Ann accepts his marriage proposal because the cigarette box she saw at Martin’s, now in Freda’s hands, made her realize she’s “been a fool.” We have seen the flashback in which she fought off Martin and accidentally killed him. The flashback isn’t in the play, and it’s especially interesting because presumably that scene really did take place, in both paths. That is, the evening orgy of confessions is one hypothetical alternative, but the manner of Martin’s death a year before, revealed in this path, is an actual event. It’s as if reliving Martin’s attack during the first path has made Ann appreciate Charles’s genuine love for her.

My seventh principle also bears on the last path we encounter. It’s a simple one: We take the final path as the correct one. Since endings are typically the place where all is revealed, we’re prepared to accept the last reiteration as what really happened. (This can be reinforced by a character’s learning curve, such as Ann’s.) Dangerous Corner is a good example.

I think we’re urged, by the second intertitle but also by the overall arrangement of the parts, to see that the quiet maintenance of civility predominated during that evening. The more sordid alternative, though given at much greater length, is what’s under the surface but what will never be acknowledged. The truth of the theft and Martin’s death, along with all the love affairs and animosities spilled out in the first version, will never be brought to light.

Other factors give the second version more weight. There are the shots I mentioned that stress the Ann-Charles relationship more, but for me the clinchers are more structural than stylistic. For one thing, both Ann and Charles play the role of raisonneur–the character(s) who explains the action and articulates central themes of the piece. In both the first path and the second, Ann echoes Priestley’s notion of our limited knowledge, saying that we prefer half-truths to the complete, factual account, the one that only God knows. And in both paths Charles warns against telling the truth, as it presents a “dangerous corner” that could lead to a smash-up. No other characters reflect so fully on the consequences of letting everything out.

Another structural factor involves the film’s beginning and the ending. The 1933 section starts with a scene in which Charles calls on Ann and once more asks him to marry her. Thanks to the primacy effect, this pair of characters becomes more salient in what follows than the married couples do. As a result, the epilogue, set on a terrace like the first one, harks back to the indubitably actual, pre-fork opening.

The fact that the movie ends with the creation of a couple, the uniting of the two characters who are the most self-aware and sympathetic throughout the film, reinforces the sense that this is the “real” outcome.

I hope you’ll read the whole essay. My purpose is to understand the dynamics of a small but increasingly common body of films. Forking-path films ask us to construct stories in unusual ways, but we quickly learn what guidelines to follow. Once the format exists, filmmakers take up the challenge of mastering it, stretching it, applying it to new material. (Edge of Tomorrow was sometimes considered Groundhog Day Goes to War against Aliens.) As filmmaking practice develops, we can track contemporary experiments and relate them to earlier efforts they are based on.

In addition, it’s worth knowing that a fairly sophisticated filmic treatment of the format appeared eighty years ago. In the essay, I find even earlier examples. And in a period when every movie seems at least 130 minutes long, it’s nice to encounter one that offers so much narrative complexity in about half that running time.

More generally, I think that probing this body of film shows the value of systematically studying narrative formats of any type. We’re used to talking about genre as a fluctuating body of conventions, but we should also study conventions that cross genres—conventions of story worlds, plot structure, and narration. These conventions can prod us to execute some unusual mental moves. Filmmakers are practical psychologists, and they’ve learned how to tease and tickle our minds. What-if movies are just one example of how norms and forms guide our understanding of story.

My first quotation from Priestley comes from Three Plays and a Preface (Harper and Brothers, 1935), ix. The second comes from Two Time Plays (Heinemann, 1937), ix.

In production, Dangerous Corner seems initially to have replaced Priestley’s what-if premise with more of a whodunit plot, while incorporating subjective sequences. According to a Variety review of an 83-minute cut before release, the explanations offered for Martin’s death by the various men are followed by something fairly unusual.

Surprise and twist, with increasing suspense, are accomplished through a shift from the factual elements to subjective processes on the part of the three women most closely related–as wives or sweethearts–with the suspected men. An innocent revolver shot precipitates the terrific speculations as each woman wonders if her man has killed himself in an adjoining room (Daily Variety, 13 September 1934, p. 3).

By the final release, however, the film had lost twenty minutes, and the result was the version we have. I haven’t seen versions of the screenplay, but I bet they’d be interesting. We’re left with other what-if questions, this time about the production of the movie itself.

Some of the basic concepts I employ here and in “Film Futures” are explained in the essay “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” online here. That essay is in turn applied to The Wolf of Wall Street in this blog entry.

Dangerous Corner (1934).