Archive for 2014

Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image

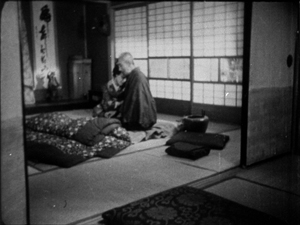

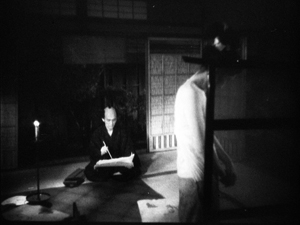

Sansho the Bailiff (1954).

DB here:

First things first: Happy birthday, Mizo-san! (He was born on 16 May 1898.)

Secondary things second: This entry is based on a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, as part of its comprehensive Mizoguchi retrospective. I want to thank my friends David Schwartz and Aliza Ma for inviting me to MoMI.

A fragile and fragmentary legacy

Mizoguchi, age twenty-eight, and Sakai Yoneko at Nikkatsu studio, 1926.

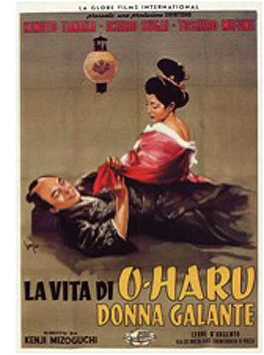

Mizoguchi Kenji’s renown in the West has flowered and faded. Like other Japanese directors, he was unknown in Europe and America before 1950. When Rashomon won the Golden Lion at Venice that year, Japanese cinema sprang onto the world’s radar. Just two years later, Mizoguchi began winning top Venice prizes with Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). His old associate Nagata Masaichi saw export opportunities in Japanese costume pictures, especially after Gate of Hell (1953) won the Academy Award, and so Mizoguchi turned out several historical films with high-tone production values. He died in 1956, after Street of Shame (1956), a return to contemporary social commentary.

In just five years, this flare of attention and the praise of the Cahiers du cinéma critics made him second only to Kurosawa in Western recognition. During the 1960s, while Japanese critics were writing him off as outdated, international critics canonized him. Here’s Andrew Sarris in 1970.

I recently saw an obscure Mizoguchi film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art without any English subtitles, which left me up the Sea of Japan without a paddle. The program notes alerted me to the plot outline, but I was generally puzzled by the personal relationships, and the picture dragged along. . . . And then at the end the beleaguered heroine walks to a restaurant on a hillside overlooking the sea, and she orders something from a waiter in white, and the camera is high overhead, and the morning mists are bubbling all around, and the camera follows the waiter as he walks across the terrace to the restaurant and then follows him back to the heroine’s table now magically, mystically empty. It is as if death had intervened in the interval of two camera movements, to and fro, and the bubbling mists and the puzzled waiter provide the Orphic overtones of the most magical mise-en-scène since the last deathly images of F. W. Murnau’s Tabu.

Mizoguchi’s reputation was based almost completely upon his 1950s work. But as ever, film distribution shaped film tastes. Soon after the 1972 success of Tokyo Story in New York, Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films began circulating many major Japanese titles. Most electrifying for my generation was an abundant set of Ozu films, the arrival of which coincided with Donald Richie’s Ozu (1974). Twenty years after Mizoguchi’s emergence, Ozu began his ascent to the top of the pantheon.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

A broader recognition of 1930s-1940s Japanese film was crystallized in the 1978 publication of Noël Burch’s book To the Distant Oberver: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film. Burch urged the case that Ozu, Mizoguchi, and other “mature” directors had done their most ambitious work well before the Western festivals and critics had caught up with them–that in fact the venerated postwar films were mannered and unadventurous compared to the artistically radical prewar work.

Since then, as Ozu (and Naruse, and many more) have risen to the pantheon, Mizoguchi has become quite obscure. Critics haven’t really boosted him much; his most famous film, Ugetsu, ranked 50th in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. Nor is the range of his work easy to sample on video. In 1976, Kristin and I were obliged to go to London to see the early Ozus not in US distribution; now, everything is on DVD. But many years later I went to Brussels for a complete Mizo retrospective, and the rare titles I saw there remain nearly unknown. His festival classics and the “Talbot canon” circulate on good-quality prints and DVDs, thanks to Criterion and Janus. But other films must be hunted down in obscure foreign DVD.

Worst of all, the survival rate of Mizoguchi’s films is appalling (although not exceptional for Japan). He made 43 films between 1923 and 1929; of these, only one survives complete. For the rest of his career he made or contributed to 42 features, of which we have 30. We lack over half his output. The physical quality of what we have varies a great deal, from gorgeous (Genroku Chushingura) to appalling (The Straits of Love and Hate, 1937, blown up from a scratched and contrasty 16mm copy). In fact, copies seem to have deteriorated. Prints I saw in the 1970s of Oyuki the Virgin (1935) were in decent shape, but many copies circulating now seem to be bad dupes of those prints, now much battered. There seems to be no systematic effort to restore what we have.

Tears are easy; tragedy is hard

I can’t deny that Mizoguchi’s fluctuating reputation is due to more than availability. He is easier to admire, even to worship, than to love. His films, though visually sumptuous, can be somber and bleak. Often unremitting tales of suffering, they lack humor (though not irony). Ozu’s mix of poignancy and comedy is much easier to enjoy than Mizoguchi’s forbidding, near-tragic despair. Ozu is also a more rigorous stylist; his signature is in every frame. While Mizoguchi was no less distinctive, he was more pluralistic in his technique.

Another obstacle: despite working with melodramatic material, Mizoguchi cools it down, sometimes to the point of remoteness. For many of his films, the prototype was Japan’s shinpa drama, an early twentieth-century theatrical tradition that blended kabuki themes and situations (e.g., the conflict of love and duty) with Western-style dramaturgy. Shinpa plays tended to concentrate on the sufferings of women in a male-dominated society. Shinpa women are victimized, exploited, and condemned; when they sacrifice themselves for men, too often the men attack them, betray them, or dump them. Mizoguchi worked many variations on these plot elements. When the American Occupation demanded more liberal films from the industry, he simply let the oppressed woman win some victory in the end.

Whether the woman wins or loses, Mizoguchi refuses to beg for tears. Some directors, notably Sirk, amp up melodrama; others, like Preminger, bank the fires. Mizoguchi seems to try to extract the situation’s emotional essence, a purified anguish, that goes beyond sympathy and pity for the characters. In The Poppy (1935), here’s how he renders the moment at which a father and daughter learn that the daughter’s suitor has abandoned her. The core dramatic action is the daughter moving from the foreground to console her father, at which point they embrace.

Some climax! No close-ups, no fast cutting, no camera movement; people withdraw from us and leave us on the outside. All of which suggests that one dimension of Mizoguchi’s artistry consists of exploring how human emotions, notably the unhappier ones, can be expressed in vivid, sometimes surprisingly “cold” pictures.

Pictures tell the story

Everybody grants that Mizoguchi makes magnificent images. He has gone down in history as a pictorialist. But his pictorialism is of a peculiar kind. We tend to think of pictorialist filmmakers as, for instance, masters of landscape, like Ford in My Darling Clementine; or exponents of abstract patterning, like von Sternberg in Shanghai Express; or buccaneers of aggressive depth, like Welles in Citizen Kane.

On each of these possibilities Mizoguchi can match the masters. Here’s a landscape from Portrait of Madame Yuki (1950; this is the scene that made Sarris swoon), a geometrical shot from Hometown (1930), and a bold depth composition from Naniwa Elegy four years before Kane.

It’s not surprising that Mizoguchi relies on the image; in his youth he studied painting (interestingly, Western-style painting at that). But he is, I think, a more fervent pictorialist than his peers.

Most movie scenes consist of a story situation mapped onto the space; the style follows, emphasizes, or shapes the story’s presentation. Suppose, Mizoguchi seems to ask, that we start with an image and ask it to become a drama. That’s in a sense what seems to happen with the Poppy example above: a striking picture develops into a story through a suite of compositional changes. Or consider this, from Sansho the Bailiff. A scene starts with a bundle of brush in a village street. Gradually it becomes the site of action: two children peep out, one by one.

Our view isn’t impeded only by the brush. A man bursts eagerly into the frame, blocking the boy and girl, followed by another man. The camera tracks a bit around the foreground post. As the scene goes on passersby will intrude into the frame.

You can’t, I think, imagine many more ways to suppress our views of the kids. We strain to see past all these obstructions, and when the view finally clears and the children are visible and come forward briefly, they turn from us…and more people pass in the foreground.

This is actually an important moment in Sansho the Bailiff: The children, kidnapped from their mother, are about to become slaves. It could be rendered with all the stops out, as a scene of brutality or high tension, but instead Mizoguchi let the dialogue (after some delay) explain what’s happening. At first you might think that Zushio and Anju have escaped from their captors and are in hiding; the unfolding image initially permits that possibility. Eventually, though, the shot, expressing the children’s fear and shame as they shrink from not only the men but the camera, holds us in its own right.

Instead of an image that is a vehicle for the story, the story is gradually born out of the changing image. To some degree, this happens in many films, but not with the persistence and rigor we find in Mizogcuhi. He talked of wanting to hypnotize the viewer, and this is done, I think, as much by the minute changes in the pictures as by the dynamics of the drama.

This version of pictorialism employs several strategies. I’ll mention just three.

Now you see it, sort of

Kiyonaga Toru, Interior of a Bathhouse (1780s).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Traditional Japanese cinema is itself heavily pictorial, from the zigzag excitement of the 1920s swordplay films to the dynamic modernity of the city dramas and the monumental gravity of historical dramas. Directors, I’ve argued in various places, cultivated a “decorative” approach to technique. Composition, camerawork, cutting, and other tactics often created flashier compositions than we find in other national traditions. As early as 1922, Ikeda Yoshinobu was creating arabesques with a bedstead, framing the faces of grieving family members (Cuckoo).

The gridded zones of the Japanese house seems to have invited filmmakers to explore a sort of Advent-calendar style, with bodies framed in different apertures (The Abe Clan, 1938). The same idea could be applied to a bar’s Art Deco wall divider (First Steps Ashore, 1932).

I’ve also argued that this love of pocketed compositions may be an effort to echo similar impulses in Japanese graphic art. The Kinoyaga woodblock print above, with its partial views of women bathing and the little windows through which we see the male attendant watching, is a beautiful example. Perhaps filmmakers adapted this eye-beguiling tactic as a way of giving cinema some cultural credentials (if not a national identity).

Most directors don’t sustain such flashy compositions. The shots function mostly as long-shots or establishing shots, or as in the Cuckoo example, as a series of brief extracts from the larger scene. Mizoguchi drew upon this decorative tradition but let it be sustained through figures moving into and out of the apertures within the frame. He creates a game of vision, a sort of fluctuating pictorial vividness that conceals or reveals or teases us with information.

One of the most vivid examples comes in this famous scene from Sansho the Bailiff. Tamaki’s leg tendons are cut, and the other enslaved women are forced to witness it. As the struggling Tamaki is peeled away from the wall and the slavemaster walks to her offscreen, the other women become visible and an older master comes slightly forward in the central square Tamaki had occupied.

As she screams, the grid isolates each woman’s fearful turning away. As with the earlier Sansho scene, dialogue comes to “button up” the unfolding of the image: The old man tells the cringing women that all runaways will punished this way.

The impact of the act is amplified not by, say, cutting to different women’s reactions, but by letting us see them all, simultaneously, in a choreography of terror.

Mizoguchi finds an abundant variety of ways to play his game of vision. Not only are figures and faces secreted in various pigeonholes of the frame, but he can tease us with some that are merely shadows or partial figures (The Poppy; Tokyo March, 1929). Sometimes the key element, such as a character’s reaction, is obscured by a semi-transparent surface, as when the embarrassed model is caught in a corner of a screen in Utamaro and His Five Women (1946).

What other directors treated as piquant flourishes, imaginative ways to arouse our visual interest before moving in to closer views, Mizoguchi saw as a way to activate any cranny of the image and invest it with expression. But for that process to unfold, he needed time.

Intensify and prolong

From the brief surviving fragment of Tojin Okichi (1930).

During the course of filming a scene, if an increased psychological sympathy begins to develop, I cannot cut into this without regret. I try rather to intensify and prolong the scene as long as possible.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Mizoguchi is famous as an exponent of long-take shooting. His earliest surviving film, Song of Home (1925) displays the Hollywood-style editing that most Japanese filmmakers mastered at the period. At some point–he says it was while shooting Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner)–he began using a method he called “one scene, one cut.” (Here “cut” apparently refers not to a shot change but to a single take, like a “cut” of meat. Hollywood filmmakers talked the same way sometimes.) That would suggest that he took every scene in a single shot, but actually he didn’t. Most of his scenes are built out of several shots, and throughout his career he would have recourse to standard analytical and shot/reverse-shot cutting for many sequences. He wasn’t as strict about the plan-sequence as, say, the Miklós Jancsó of the 1960s and 1970s was.

Still, he definitely used longer takes than most filmmakers of his day. The shots in most of his post-1935 films average between twenty-five and forty seconds in length, which means that some shots run minutes. Many of his long takes are made from static camera positions, as in the above examples. But he didn’t shrink from camera movements, either tracking shots or crane shots. Kristin and I discuss an example from Sisters of Gion in Film Art, and in his later films he enjoyed establishing a setting with a high-angle crane shot before moving in to details. He also enjoyed riding the crane and directed from it even if the shot was static.

Fixed frame or moving shot, Mizoguchi’s long takes can extract an arc of pictorial-dramatic intensity. That arc can have a clear-cut ABA pattern. In My Love Has Been Burning, the liberal feminist Eiko finds her weak lover Hayase drunk and despondent. He’s no longer the idealist she thought he was, but he defends himself as changing with the times.

Hayase says he’s got some money now and they can marry. When she doesn’t warm to the idea, he attacks her, and suddenly her face gets enlarged, upside down, when he slams her to the floor. This is the first high point of the scene.

They struggle out of frame, but Mizoguchi doesn’t follow them.

Immediately there’s a second assault on our vision: a screen abruptly crashes into the foreground.

After it settles into place, Eiko flees back into the frame, pausing by the doorway. She leaves, and Hayase totters to the same spot looking after her.

The shot has built up to one spike, the image of Eiko on her back, her face close to us, and then to a second, with the collapsing screen. At the end, the site of action returns to the beginning: a figure near the doorway, something else (Hayase, the screen) in the foreground. But in the course of this ABA pattern, the game of vision has concealed as much as it has revealed.

Throughout his career Mizoguchi experimented with the patterning of his long takes, often building them around advances to and away from the foreground, as in these examples. This tactic can be seen in a pure state in the most intense scene of the Occupation feminist film Victory of Women (1946). Here the characters rush the camera and shrink from it as the emotional pitch rises.

Tomo’s husband has just died, and she has already told her friend the lawyer Hiroko that she has no more milk for her baby. Tomo calls on Hiroko, who invites her to come in. The camera obediently tracks back as she enters and sits.

Hiroko, at first oblivious to the distraught Tomo, begins to question her. At first Tomo says that nothing has happened to her baby, and she slides away from Hiroko. She tells her that her husband died the day that they had met in the street. She edges closer to the camera.

Sobbing, she tells Hiroko that the baby is dead; he died sucking her breast. She falls out of the frame and as the camera pulls back Hiroko bends to comfort her. But she also asks Tomo to tell her exactly what happened.

Tomo confesses that staring at her crying baby, she hugged it so close that she may have killed it. As she rises, she cries, “My baby!” And she turns and staggers, like Ayako in Naniwa Elegy, to the most distant point of the set–as if hoping to escape both Hiroko and the camera.

Track in as Hiroko goes back to her, at the spot at which the shot’s action started. Once more the two women advance to the camera, with Hiroko nearly dragging Tomo back to the center. But when Hiroko suggests she go to the police, Tomo slides quickly away from her, back to us, and the camera abruptly pulls back to accommodate her. As when the paper wall crashes into the frame in My Love Has Been Burning, a spike in the drama is accompanied by a second burst into the foreground.

Hiroko rushes to embrace Tomo, assuring her that “You must not run from life, but face it!” Mizoguchi’s staging favors the doubt and fear on the face of Tomo, not the somewhat complacent Hiroko.

As Hiroko hurries off to dress for going out, Mizoguchi’s camera lingers on Tomo, not only pitiable but justifiably worried that she is condemned. As she bends and glances to and fro, Mizoguchi ends the seven-minute scene on an image of a woman with nowhere to turn. This is a terrifying final image: Is this what Hiroko meant by “facing life”?

Some of Mizoguchi’s earlier works go further still. Instead of a coming-and-going pattern, in which the characters confront the camera and then retreat, we get a going-and-going one. The most famous, about which I’ve written probably more than I should, comes in Naniwa Elegy, when Ayako, telling her boyfriend of her sexual infidelity, retreats from him, and from us.

A Western director–Wyler, say, as in The Little Foxes, or Huston–would have put the camera at exactly the opposite point, in the corner of the wall, so that Ayako would advance toward us and Nishimura’s reaction would be constantly visible in the background. It’s as if Mizoguchi anticipated such full-disclosure framing (before these men had even made their films!) and dismissed it as too easy. By suppressing characters’ expressions, he throws our attention onto Ayako’s voice and her posture, while also sustaining some suspense about how Nishimura will respond to her revelations.

Mizoguchi finds a huge variety of ways of turning images into drama, and he has left us a rich repertory of staging strategies–if we only look. Young filmmakers, are you looking?

Filigree

Tanaka Kinuyo and Mizoguchi Kenji in Venice, early 1950s.

[The long take] allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Once Mizoguchi enhances the decorative frame with surfaces and holes bristling with possibilities, and once he sustains it in time through the long take, he can build his scenes out of slight changes in the image–changes that add nuance and expressive depth to the drama. We’ve seen this already in several passages, but I want now to stress how this sharpens our attention and engagement. The restraint of Mizoguchi’s handling (restraint within sumptuousness, I should say) trains us to watch for the tiniest shift in pictorial emphasis. This is the third strategy I want to mention.

In Lady of Musashino (1951), minor changes around the deathbed drive our eye to the profile of the dying Michiko.

Likewise, when Oishi in Genroku Chushingura reads the master’s poem, sent to his vassals after his suicide, he lowers the paper just a little at the climax, and the gesture is echoed in the men’s slumping forward even more. (This is a movie largely made of just-noticeable differences.)

The just-noticeable differences can be triggered by tiny changes in the avenues of our vision. In Street of Shame, the brothel owner, turned from us in the middle ground, first reveals Mickey and the delivery boy down the left corridor. When he shifts his head, Mizoguchi closes off that view and allows faces and bodies of the prostitutes to fill up the corridor on the right.

Bolder movements can yield even briefer glimpses. When Oharu reads the message from her dead lover, Mizoguchi gives us a “decoy” shot: Her mother stands guard on the left and in the distance we see the door through which the father is expected to come. But the scene’s real action is taking place behind the hanging kimono, where Oharu reacts painfully to the letter. Since we can’t see her, only her wavering voice and the trembling of the kimono convey her emotion. Suddenly she starts to thrash around, her mother leaps toward her, and a tussle ensues. The kimono is pulled down in a heap.

What’s all the fuss? What is Oharu doing? The answer is given to us in an almost subliminal detail, the knife that flashes through the lower right corner of the shot in only two frames on the 35mm print. Oharu races out of the shot, bent on suicide.

So the nuances that spring up may be protracted or simply glimpsed, but either way they become the product of the image giving birth, through its transformations, to the drama. The strategy is just as applicable to closer views as to long shots. In one scene of Woman of Rumor (1954), the keeper of an elegant brothel notices a young man getting cozy with her daughter. The tension is exacerbated by the fact that she hopes to nab Dr. Hatoba herself. As the two talk, Mizoguchi buries Hatsuko in the rear of the scene, her presence signaled by a shadow and her kimono sleeve poking out from a screen.

Mizoguchi cuts directly in and provides a medium-shot of Hatsuko peeking. This might seem safe and conventional, especially in the light of daring choices like those made in Naniwa Elegy. But Mizoguchi now wants to trigger the game of vision around the woman’s face and the edge of the screen. As she listens, he teases us with a little suite of changing expressions and minute gradations of partial blockage–a sort of pictorial vibrato.

As Hatsuko edges out to approach the couple, Mizoguchi switches our attention to small, nervous hand gestures.

Once installed behind the couple, Hatsuko starts the whole process again, from eye-catching sleeves to peekaboo eavesdropping.

Mizoguchi was a fairly pluralistic filmmaker, so the strategies I’ve itemized don’t exhaust everything we encounter in his movies. Sometimes he builds scenes in a fairly orthodox way, with traditional framing and cutting. But taken as a whole, his films offer a magnificent repertory of ways in which the image can, under pressure, deepen and enrich a dramatic situation. Unlike most of today’s filmmakers, he cares about rigor, nuance, and austerity–while at the same time working with scenes of intense emotion. Admire him, worship him, love him, or just respect him: film culture can’t live fully without him.

Thanks, over forty years of viewing, to the Japan Society of New York, the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute (formerly the Japan Film Library Council), Dan Talbot and José Lopez of New Yorker Films, and the Brussels Cinematek, especially Gabrielle Claes.

The MoMI series runs until 8 June. It begins on 16 May at the Harvard Film Archive and on 19 June at Pacific Film Archive. For Fandor’s Keyframe daily, David Hudson has a varied roundup of response to MoMI’s series.

Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema offer many Mizoguchi films on DVD, some on Blu-ray. See also Criterion’s Hulu Plus offerings. Digital Meme sells DVDs of some early Mizoguchis, with benshi accompaniment; the exasperatingly brief fragment of Tojin Okichi is on volume 2..

My quotation from Andrew Sarris comes from “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970,” in The Primal Screen (1973), 60-61.

Good clichés will never die as long as journalists need to crank out copy. The MoMI retrospective has revived the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi tug-of-war, this time among New York critics (here and here). Such sideswipe critiques and hosannas can’t really be backed up within the space limits of popular publishing. Moreover, I think that such quick assertions of taste block close consideration of the work. Once you’ve dismissed a filmmaker, you’re unlikely to probe further, and your readers will probably be even less curious. I defected years ago from the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi skirmishes.

The fact that every decade or so Mizoguchi is “rediscovered” through a retrospective indicates his elusive reputation. Among English-language scholars, the 1980s was the big period. Dudley Andrew wrote a still indispensable reference book on Mizoguchi in 1981, and Keiko McDonald offered a penetrating critical survey in 1984. Both volumes, now rare and costly, deserve to be made available in digital editions. Robert Cohen’s two-volume dissertation “Textual Poetics in the Films of Kenji Mizoguchi” (UCLA, 1983) was also significant. Since then, incredibly, we have had only one more overview in English, Mark Le Fanu’s Mizoguchi and Japan, along with an in-depth analysis of some 1930s films, Don Kirihara’s award-winning Patterns of Time. Sato Tadao’s monograph was published in Japanese in 1982, but it’s only recently been available in (a somewhat problematic) English translation (as Kenji Mizoguchi and the Art of Japanese Cinema). Two of my stills are drawn from this book. The French have been more consistently productive, with several studies over the years. A thorough account in Spanish is by the prolific Antonio Santos.

For some background on Western rankings of Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, and Ozu, see this interview with the late Hiroko Govaers. Hiroko was instrumental in bringing many classic Japanese films to Europe and the U.S.

Some of the material in today’s entry comes from Chapter 3, “Mizoguchi, or Modulation,” of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. That offers a much fuller account of what I think Mizoguchi is up to, although today’s blog offers some points and examples not in the chapter. Offshoots of the book’s argument can be found in this online update, and in this blog entry, which compares Mizoguchi with his sort-of-rival Wyler. My oldest piece on the director, “Mizoguchi and the Evolution of Film Language,” in Stephen Heath and Patricia Mellencamp, eds., Cinema and Language (1983), 107–117, contrasts his work with Western practitioners of deep-space staging. Background on the “decorative” impulses in traditional Japanese cinema can be found in Essays 12 and 13 in my Poetics of Cinema, and in early portions of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema.

P. S. 29 June: Thanks to Jeff Fort for correction of a title in the original blog post!

Sansho the Bailiff.

Alexander Payne’s vividly shot reality

Election.

Kristin here:

Both David and I missed almost all of this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. I was in Egypt wearing my archaeologist’s hat and working on ancient statuary, and David was attending the Hong Kong International Film Festival. (See his reports, here and here.) Luckily we made it back just in time for Alexander Payne’s spring visit to Madison.

I first met Alexander at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna. He already knew who I was from having read Film Art: An Introduction, and we started chatting. We were in a small crowd outside the Arlecchino cinema, where a screening was running late. I asked Alexander what he had seen at the festival that he liked. He said he had come from a screening of Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm and thought it was a masterpiece. Right away I knew that this man has impeccable taste in movies. (Alexander further proved this during his recent visit, saying that his favorite three films of Il Cinema Ritrovato were Ingeborg Holm, Naruse’s Wife, Be Like a Rose, and Rossellini’s Il Generale Della Rovere.)

I first met Alexander at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna. He already knew who I was from having read Film Art: An Introduction, and we started chatting. We were in a small crowd outside the Arlecchino cinema, where a screening was running late. I asked Alexander what he had seen at the festival that he liked. He said he had come from a screening of Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm and thought it was a masterpiece. Right away I knew that this man has impeccable taste in movies. (Alexander further proved this during his recent visit, saying that his favorite three films of Il Cinema Ritrovato were Ingeborg Holm, Naruse’s Wife, Be Like a Rose, and Rossellini’s Il Generale Della Rovere.)

Alexander is a friend of Jim Healy, head programmer for the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cinematheque screening series and of the Wisconsin Film Festival. Jim seems to know half the people in the film industry as well as in the festival and archival spheres; he has already brought Tim Hunter and Joe Dante to campus. I knew he hoped to bring Alexander as well, so I put in a pitch for the idea, mentioning how enthusiastic the film students and buffs are in Madison and how he would enjoy speaking with audiences here, who would ask interesting questions. Luckily for me that turned out to be true, a mere nine months later. (Left, Alexander and Jim in a local Madison burger joint.)

Alexander Payne, cinephile

Alexander participated in a number of events here in Madison, some associated with the Wisconsin Film Festival and others with the Department of Communication Arts. The first was a session of our divisional film colloquium, which  began with David and Alexander in discussion onstage (right) and then opened for questions from the faculty and graduate students.

began with David and Alexander in discussion onstage (right) and then opened for questions from the faculty and graduate students.

The conversation began with Alexander recalling how he fell in love with movies, which he reckons happened at about the age of four. He watched mainly older movies. In those days there were rival houses in his hometown of Omaha. His father owned a restaurant in Omaha, and for some reason one of his suppliers, Kraft, gave him a regular-8mm movie projector. Alexander started collecting films, buying prints initially from the now defunct Castle company and later from the still functioning Blackhawk Films.

These included all twelve Chaplin shorts made at Mutual. Many years later, Alexander supported the restoration of the last of that set, The Adventurer. That’s what had brought him to Bologna. He introduced the film, which was shone as one of several new restorations in the Essanay/Mutual Project of the Fondazione Cineteca Di Bologna and Lobster Films. (See here for information on the project and program notes for this year’s screenings.) It was screened at one of the 10 pm programs in the Piazza Maggiore, with Sjöström’s The Outlaw and His Wife, also newly restored.

Jumping back to Alexander’s progress as a cinephile, he became an undergraduate at Stanford, studying history and Spanish. From there he moved on to UCLA for an education in filmmaking, and “thought it was heaven.” He loved it so much that he delayed starting his filmmaking career and stayed on to see more film’s in the famous Melnitz Hall screening room. In those days, 35mm prints were regularly shown, including nitrate originals. (Probably around ten years ago I saw a nitrate print of Trouble in Paradise there, being shown for a class. It definitely was heaven.)

There he recalls seeing such things as an Antonioni retrospective and Double Indemnity. When he was in his 30s, he fell in love with Italian and Japanese cinema. Now that he has reached his 50s, he has broadened his interests to study the films of Hollywood directors like Michael Curtiz and Raoul Walsh. He admires the conciseness of their films: “Film,” he says, “is a constant search for economy.”

Alexander’s love of Italian films was in evidence at one of the final events of the Wisconsin Film Festival. He had been asked to choose an older film that he could introduce and answer questions about afterward. His choice was Il Sorpasso (1961, Dino Risi). The auditorium at our local arthouse multiplex, Sundance 608, was packed with a very enthusiastic audience indeed. (Left, Alexander after being introduced by Jim Healey.)

Alexander’s love of Italian films was in evidence at one of the final events of the Wisconsin Film Festival. He had been asked to choose an older film that he could introduce and answer questions about afterward. His choice was Il Sorpasso (1961, Dino Risi). The auditorium at our local arthouse multiplex, Sundance 608, was packed with a very enthusiastic audience indeed. (Left, Alexander after being introduced by Jim Healey.)

The next evening, Alexander did the same for a screening of Nebraska at Union South. Again a full house, and again an audience eager to ask questions.

In between such events, we shared some restaurant meals. Alexander, Jim, and David sounded like some contrapuntal version of the Internet Movie Database, tossing titles, directors, and other film credits back and forth.

During these conversations, and indeed every other conversation we had with him, Alexander would pull out a small pocket notebook (though paper napkins sometimes substituted) and write down any intriguing-sounding title of a film he hadn’t seen. Not only a cinephile, but a systematic one.

Not surprisingly, during the colloquium discussion the issue of Nebraska being shot in black-and-white came up. David mentioned that Bong Joon-ho had said to him (while they were both jury members at this year’s Hong Kong Film Festival) that every director wants to make a black-and-white movie.

Given his love for older films, Alexander considers that “Our great film heritage is black and white.” Inevitably, during the press junkets for Nebraska, reporters asked him why he made the film in black and white. What he wants to know is, “Why is that the first question?”

Alexander agrees with Bong: “I don’t think a director is really a director until he or she has made a film in black and white.” He approached Paramount with the idea of making Nebraska as a black-and-white film and argued that it would be viable because it had a low budget of $12 million. He adds that directors have faced the same arguments against black and white since the 1970s, as when Peter Bogdanovich was making Paper Moon. The TV contracts specify color.

Alexander wanted to shoot Nebraska on film, but the only black-and-white stock available had an ASA of 200, which would not be effective for night shooting. He had to shoot digitally and add contrast and grain afterward to get a film look.

He definitely regrets the loss of film, which he considers superior to video: “I think flicker will always be superior to glow.”

Alexander says he is a big fan of the 1970s because he was a teenager at the time. He thinks that a lot of films made then and released into regular theaters could not be shown today outside arthouses. Films then were judged by their closeness to reality, not their distance from it. For him, “There’s just a consistently fine product being turned out between The Graduate [1967] and Raging Bull [1980].”

It was the period when a generation of filmmakers came to prominence, filmmakers who today are the grand old men of Hollywood. David pointed out that Alexander has often been mentioned as part of a later generation that included such directors as Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson. Alexander agreed that there was the “Class of 1999” that included films like Election and Fight Club (putting David Fincher in the same group). He says of these directors, “We’re friendly enough.” But he envies the Spielberg, Coppola, Scorsese, Lucas generation because they were able to help each other out in filmmaking. His generation doesn’t socialize much, though he said he had seen Soderbergh recently.

The Milos Forman of Nebraska

For anyone who had been unaware that Payne comes from the vast territory in the middle of the USA that encompasses the Midwest and Great Plains and is generally known as Flyover Territory, his latest film makes that point clear. He was born and raised in Omaha, and still lives part of the year there. As he explained in the colloquium discussion, “I’m one of those people in the arts who are interested in exploring where they’re from.” This is not to say that all of his films are set in Nebraska, but four of the six features take place there, explicitly or implicitly.

Citizen Ruth has no identifiable setting, as far as I could tell, though its milieu is clearly centered in small-town life in the country’s midsection. It was shot in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha. Election doesn’t stress the fact, but close shots of newspaper stories reveal that its story is set in Omaha. Warren Schmidt lives there as well, and his road trip to his daughter’s wedding takes him to Denver and brings him back home. Payne’s next two films were set in quite different parts of America: Sideways in San Diego and California wine country and The Descendants in Hawaii. Nebraska chronicled David Grant’s journey with his father Woody from Billings, Montana, to Lincoln, taking in several rural and small-town locations along the way.

Each story mixes humor and pathos, including both satirical swipes at locals and great affection for them. It’s hard to pin down their genres. (The Internet Movie Database classifies About Schmidt as a comedy/drama and Nebraska as an adventure/drama.) In the colloquium, Payne remarked of Nebraska, “I call it my own Czech Republic. I get to make Milos Forman films about it.”

It is a cliché to say that the settings in which a film’s action takes place become a character in the drama, but Payne’s films really do manage to keep us aware of the surroundings to surprising extent. Payne says that when he discusses a film with his cinematographer and production designer, he says he wants “Vividly shot reality.”

Vivid can simply mean beautiful, and there are many such landscapes, as in The Descendants:

But it need not mean that. The choice of framing in the opening scene of Election, with the fence in the foreground and the school crouched ominously high on the hill tend to make it look like a prison:

Emphasis on locales can be created by something as simple as a slight wide-angle lens that adds dimension to a house, making it more prominent within its surroundings, as in The Descendants, About Schmidt, and Nebraska, where the vegetation framing the building, ranging from lush to ordinary to sparse, help define the homes of the main characters:

To achieve the desired vividness, Payne often chooses to use real interiors, even if that limits the types of set-ups he can make. The result can be busy but spacious and attractive, as in The Descendants:

Or the constraint can turn to an advantage, as in the confined arrangement filmed from a television’s point of view for the “That Impala you used to have …” long take in Nebraska:

This latter scene exemplifies something else that Payne considers crucial for achieving realism: the addition of extras and small roles, often played by non-actors found in the area where location filming is occurring.

Alexander sometimes uses symmetry to make a fairly ordinary locale more vivid, as in these planimetric shots from Sideways and About Schmidt:

Vivid shots can make a thematic point, as in The Descendants. Shots of Matt and his daughters being driven through their unspoiled ancestral land lead to a view of them being driven up to the sort of elegant resort that could be built on that land if they sell it. The second shot is pretty and well composed, but the juxtaposition with the series of shots that preceded it should make us sense it as slightly menacing as well:

I’ve stuck mainly to long shots here, since that’s where the vivid realism tends to come. There are many unusually close views of characters as well, which contrast with these long shots. There we tend to get the psychological side of these films, which are basically character studies. This contrast may be what gives Alexander’s films a sense both of place and of intense concentration on characters.

Alexander Payne, storyteller

We all know that Oscar wins and nominations don’t always go to the actual best films of the year. But they do reflect something about the reputation of a filmmaker within the industry. Alexander has had two films nominated for best picture: The Descendants and Nebraska. That these nominations are not simply the result of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science’s switch to a ten-nominee best-picture category is reflected in the fact that he has been nominated for best director three times: Sideways, The Descendants, and Nebraska. He and his co-writers have also been nominated three times for best adapted screenplay: Election, Sideways, and The Descendants. The only film which Payne did not co-write, Nebraska, received an nomination for best original screenplay, by Bob Nelson. All these nominations produced two wins, for the screenplays of Sideways and The Descendants. Clearly Alexander is recognized in Hollywood as a fine storyteller.

Apart from Citizen Ruth and Nebraska, all of Alexander’s films are based on novels. In the colloquium discussion with David, he said he prefers adapting novels, which are ready-made stories. He doesn’t have the original ideas, but he can deal with them almost like a documentarian filming an imagined reality. Most of the novels have been based on the authors’ own experiences, and most of them are regional. “You can find a world and have a dialogue with it.”

His sources are generally not well-known novels. None of the Jane Austen-style prestigious literary property here. Neither Election nor Sideways had been published at the point where he decided to adapt them. The Descendants was not a well-known book. As his first project out of film school, Alexander and Jim Taylor, who would collaborate on several scripts, wrote an original one about a retired man in Omaha. When no one in Hollywood was interested, they went on and made Citizen Ruth and Election. Once Election became a critical, if not a commercial, success, they were able to move on to a more ambitious project. In the late 1990s, Louis Begley’s novel, About Schmidt, was suggested to them as a possible vehicle for Jack Nicholson. They derived some elements from it, combining them with their earlier script. It was, by the way, Alexander’s most expensive film at $32 million, half of which went for Jack Nicholson’s fee.

[Thanks to Jim Healey for clarifying About Schmidt‘s origins; this paragraph has been re-written to incorporate the information he provided.]

Clearly he values the tight unity and narrative economy that are characteristic of the studio age of Hollywood filmmaking: “You want your screenplay as streamlined as possible.” That doesn’t mean following a formula, however. He considers that the screenplay manuals that have been so influential, like those of Syd Field and Robert McKee, “destructive.” He dislikes their blanket generalizations. David pointed out that Matt’s voiceover narration in The Descendants is used to provide exposition, but then tapers off at about the midway point. Alexander responds that manuals claims that voiceover should not be used, but that if it is, it should either be used throughout or only at the beginning and end. These strictures he considers absurd. (Interestingly, many classic studios films start with a voiceover that doesn’t return at the end.)

During the colloquium discussion, Alexander remarked, “I like films which are entertaining and charming.” It’s a generalization that could apply to classical studio filmmaking, and it applies to his films as well. These are well-made films made on the whole along classical lines. Their main characters have goals, struggle toward them, meet obstacles, and usually follow an arc at the end of which they have a sudden realization.

Those goals, struggles, and growth also follow a pattern that one could point to in making a case for a thematic consistency in Alexander’s work. These are mostly films where characters struggle against some misfortune or obsessive hatred and eventually come to some sort of reconciliation with their situation.

Warren Schmidt deals with retirements, the death of his wife, and the marriage of his daughter into a family that disgusts him. He concludes that his life has been an utter waste, and yet a sudden realization that a casual act of kindness has made a difference to another person (a six-year-old orphan in Africa whom he has “adopted” through a charity) rescues him from his despair.

In Sideways, Miles cannot accept that his ex-wife has left him and is about to remarry, and he also hopes to find a publisher for his unwieldy, long novel. Only after he accepts both the failure of his marriage and the impossibility of publication can he move on to a possible new romance. In The Descendants, Matt overcomes his rage over his comatose wife’s infidelity in time to bid her a sincere, grief-filled farewell before she dies. In Nebraska, David Grant struggles to convince his father Woody that his delusions, perhaps brought on by increasing dementia, are absurd, but he finally realizes that humoring the old man is a kinder approach for all concerned.

Election, being an early work, largely avoids this pattern. Jim conceives a hatred for Tracy that he never overcomes. He manages to pull himself together after the failure of his marriage and his firing from his high-school teaching post, finding a new romance and a modest job as a guide in a New York museum. Still, his last glimpse of Tracy as an apparently successful assistant to a major politician is resentful and dismissive, as he continues to view her as he had during her candidacy for student president. Here there is no reconciliation in the main plotline.

The films also tend to follow a well-balanced structure that at least sometimes conforms to the four-part structure I have outlined in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and in this blog entry. Election, for example, has a major turning point that comes halfway through: Tracy notices that one of her posters has begun to peel off the wall (see top), and her struggle to re-attach it leads her to lose control for once and destroy her opponent’s posters. It’s a moment that Jim could legitimately use to disqualify her as a candidate, but his own incompetence and her cleverness and ruthless resistance of his accusations ultimately lead to his failure and her success. The Descendants has a well-balanced four-part structure as well.

There is also a playfulness about these films that fits Alexander’s “entertaining and charming” description of classical films. Both Election and About Schmidt, for example, contain inserts showing the protagonists’ absurd visions of themselves as wildly successful, Jim as a Marcello Mastroianni-like sophisticate and Schmidt as a business tycoon:

What about the future? Alexander revealed that after Sideways, he and Taylor embarked on an original screenplay, which now has been revived as a current project. It would be a big-budget, effects-driven film. If the project comes to fruition, he dreads the prospect of doing storyboards for the first time. His devotion to historic films remains unchanged, however. He plans to be at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, where we hope to catch a meal with him and go on throwing favorite titles back and forth.

Why do reporters start by asking why Nebraska is in black and white? Having studied press junkets for The Frodo Franchise (see the section on frequently asked questions, pp. 123-132), I suspect that the studio is behind it. Basically publicity departments plant a small number of subjects they want reporters to talk about in the press releases, EPKs, and other items they use to guide the press. Reporters batten onto these as the things their readers would be most interested in, and they ask about them and write about them ad nauseum. All this means that filmmakers have to suffer through this same limited repertory of questions dozens, perhaps hundreds of times, struggling each time to say the same thing in a different way. The price of fame.

We have long included an example from Election in Film Art, where we quoted Alexander as a way of showing that directors deliberately set up patterns of motifs.

About Schmidt.

Unveiling Ebertfest 2014

Kristin here:

In the early days of Ebertfest, Roger personally introduced every film at this five-day event, which took place this year from April 23 to 27. He would be onstage for the discussions and question sessions after each screening, often joined by directors, actors, or friends in the industry.

In the summer of 2006, there began the long battle with cancer that Roger fought so determinedly. He withdrew gradually from full participation in the festival that he had founded in his hometown of Champaign-Urbana sixteen years ago. He struggled to immerse himself in the festival, even though repeated surgeries had robbed him of his voice. He introduced fewer films, doing so with his computer’s artificial voice, and when even that became too taxing, he sat in his lounge chair at the back of the Virginia Theater, enjoying the event and occasionally appearing onstage with a cheery thumbs-up. Finally, last year on April 4, less than three weeks before the fifteenth Ebertfest, he passed away. That year’s festival became a celebration of his life.

The celebration continued this year, though on a more upbeat note. Some films were chosen from a list that Roger had left to his wife Chaz and festival organizer Nate Kohn, and they selected others in the same indie spirit. The tradition of showing a silent film with musical accompaniment was maintained. As always, the festival passes sold out, and the crowd, including many long-time regulars, enthusiastically cheered both films and filmmakers.

The tributes

Roger did not live to see the documentary devoted to his life and based on his popular memoir of the same name, Life Itself. It premiered in January at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. He participated in its making, however, encouraging director Steve James (whose 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams Roger had championed) to film him during the final four months of his life. Some of this candid footage reveals the painful and exhausting treatments Roger underwent, but much of it stresses his resilience and the support of Chaz and the rest of his family.

Life Itself was the opening night film. James has done a wonderful job of capturing the spirit of the book and in assembling archival footage and photographs, interspersed with new interviews. The result is anything but maudlin, with a candid treatment of Roger’s early struggles with alcoholism and an amusing summary of Roger’s prickly but affectionate relationship with his TV partner Gene Siskel.

Life Itself was picked up for theatrical distribution by Magnolia Pictures and will receive a summer release, followed by a showing on CNN. (Scott Foundas reviewed the film favorably for Variety, as did Todd McCarthy for The Hollywood Reporter.)

Another tribute followed the next day, when a life-size bronze statue of Roger by sculptor Rick Harney was unveiled outside the Virginia Theater (above). Harney portrays Roger in his most famous pose, sitting in a movie-theater seat and giving a thumbs-up gesture. There is an empty seat on either side of him, so that people can sit beside the statue and have their photos taken. (See the image of Barry C. Allen in the section “Of Paramount importance,” below.)

Far from silent

Roger was a big fan of the Alloy Orchestra, consisting of (L to R above) Terry Donahue, Ken Winokur, and Roger Miller, who specialize in accompanying silent films. They have appeared several times at Ebertfest, playing original music for such films as Metropolis and Underworld. Rather than taking a traditional approach to silent-film music, using piano, organ, or small chamber ensemble, they compose modern scores, played on electronic keyboard combined with their well-known “rack of junk” percussion section, including a variety of found objects, supplemented with musical saw, banjo, accordion, clarinet, and other instruments. The result is surprisingly unified and provides a rousingly appropriate accompaniment to the silents shown at Ebertfest over the years.

I have had the privilege of introducing the film and leading the post-film Q&A on some of these occasions, including for this year’s feature, Victor Seastrom’s 1924 classic, He Who Gets Slapped. (Swedish director Victor Sjöström used the Americanized version during his career in Hollywood.) I put the film in context by pointing out three important historical aspects of the film. First, it was the first film made from script to screen by the newly formed MGM studio, formed in 1924 from the merger of Goldwyn Productions, Metro, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. (Two earlier releases by MGM were Norma Shearer vehicles which originated at Mayer.) Second, it was probably the film that cemented Lon Chaney’s stardom, after his breakthrough role as Quasimodo in the 1922 Hunchback of Notre Dame. Starting in 1912, Chaney had been in well over 100 films before Hunchback, many of them shorts and nearly all of them supporting roles. Third, He Who Gets Slapped was Seastrom’s second American film after Name the Man in 1923, and a distinct improvement on that first effort.

Naturally MGM wanted a big, prestigious hit for its first production, and He Who Gets Slapped came through, being both a critical and popular success–and also boosted Norma Shearer to major stardom. Seastrom and Chaney both stayed on at MGM, though the former returned to European filmmaking after the coming of sound and Chaney died in 1930.

I was joined for the post-film discussion by Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, and we talked with Donahue and Winokur while Miller sold the group’s CDs and DVDs in the festival shop. They revealed that this new score had been commissioned by the Telluride Film Festival and that it was a project that appealed to their taste for off-beat films. There were many questions from the audience, and we suspect that the Alloy Orchestra will continue to be a regular feature of the festival.

A cornerstone of indie cinema

Although Roger was occasionally criticized for supposedly lowering the tone of film reviewing by participating in a television series, he and partner Gene Siskel regularly tried to promote indie and foreign films that didn’t get wide attention. Roger did the same in his written reviews, and Ebertfest was originally known as the “Overlooked Film Festival.” Inevitably it was shortened by many attendees to “Ebertfest,” and eventually that name became official. It reflects the wider range of films that came to be included, with the silent-film screening and frequent showings of 70mm prints of films like My Fair Lady that were hardly overlooked.

Among Roger’s friends was Michael Barker, co-founder and co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, one of the most important of the small number of American companies still specializing in independent and foreign releases. A long-time Ebertfest regular, Barker usually brings a current or recent release to show, along with filmmakers or actors. This year he was doubly generous, bringing Capote (2005, above), to which Roger had given a four-star review, and the current release Wadjda (2012).

Roger never reviewed the latter, but it is certainly the sort of film that he loved: a glimpse into a little-known culture by a first-time filmmaker with a progressive viewpoint. Wadjda is remarkable as the first feature film made in Saudi Arabia, where there are no movie theaters. Moreover, it was made by a woman, Haifaa Al-Monsour, and tells the story of a little girl who defies tradition by aspiring to buy and ride a bicycle in a country where this, like women driving cars, was illegal. (Below, Wadjda learns to ride a bicycle on a rooftop, hidden from public view.)

Both the film and Al-Monsour thoroughly charmed the audience. Barker interviewed her afterward, and she revealed that, not surprisingly, the making of the film was touched by the same sort of repression that it portrays. Women are not allowed to work alongside men in Saudi Arabia, so Al-Monsour had to hide in a van while shooting on location. Given that there is no cinema infrastructure in the country, the film was a Saudi Arabian-German co-production, with Arabic and German names mingling in the credits. We also learned that it has since become legal for Saudi girls to ride bicycles. Perhaps someday filmmaking will become more common there, and male and female crew members can work openly together.

Naturally Wadjda was made with a digital camera, since this new technology is crucial to the spread of filmmaking in places like the Middle East where there is little money or equipment for production. In contrast, Capote was shown in a beautiful widescreen 35mm print that looked great spread across the entire width of the Virginia’s huge screen. Naturally the screening became a tribute to the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, giving his only Oscar-winning performance (out of four nominations) in the lead role.

Barker had brought with him a surprise guest, Capote‘s director, Bennett Miller, whose appearance had not been announced in advance. He discussed how he and scriptwriter Dan Futterman learned that there was a second, rival Capote film in the works, Infamous (2006), which also dealt with the period when the author was researching In Cold Blood. Miller and Futterman decided to press ahead, a wise move in that their film drew more attention than did Infamous. Much of the discussion was devoted to Hoffman’s performance and his acting style in general.

Capote was Miller’s first fiction feature. He had come to public attention with his documentary The Cruise (1998), which Roger had given a brief three-star review. Roger continued his support for Miller with a four-star review for Moneyball (2011). It’s a pity he did not live to see Miller’s latest, Foxcatcher, which will be playing in competition at Cannes in May.

Overlooked no longer

Perhaps no young filmmaker better demonstrates the impact that Roger’s support can have on a career than Ramin Bahrani. Roger saw his first feature, Man Push Cart, at Sundance in 2006 and invited it and the filmmaker to the  “Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

“Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

His second film, Chop Shop, brought him to Ebertfest a second time, in 2009. (Roger’s program notes are here, and his four-star review here.) At about that time, Bahrani’s third film, Goodbye Solo, was released. Given its modest budget, it did reasonably well at the box office, grossing nearly a million dollars worldwide (in contrast to Man Push Cart‘s roughly $56 thousand). Bahrani inched toward mainstream filmmaking with At Any Price (2012), starring Dennis Quaid and Zac Efron, and he is currently in post-production on 99 Homes, with Andrew Garfield, Michael Shannon, and Laura Dern. During the onstage discussion, he spoke of struggling to maintain a balance between the indie spirit of his earlier films and the more popularly oriented films he has recently made.

Bahrani visited Ebertfest for a third time this year, belatedly showing Goodbye Solo. We had enjoyed this film when it came out, and it holds up very well on a second viewing. It’s a simple story of opposites coming together by chance. An irrepressibly talkative, friendly immigrant cab driver, Solo (a nickname for Souléymane), becomes concerned when a dour elderly man engages him for a one-way trip to a regional park whose main feature is a windy cliff. He fears that William is planning suicide. Solo arranges to drive William whenever he calls for a cab and even becomes his roommate in a cheap hotel. Gradually, with the help of his young stepdaughter Alex, he seems to draw William out of his defensive shell.

As in Bahrani’s earlier films the main character is an immigrant and played by one, using his own first name (Souléymane Sy Savané). He’s the main character in that we are with him almost constantly, seeing William only as he does. William is a vital counterpart to him, however. He is perfectly embodied by Red West, an actor who worked for Elvis Presley and did stunt work and bit parts in films and television since the late 1950s. He may look vaguely familiar to some viewers, but he’s not really recognizable as a star and comes across convincingly as an aging man buffeted by life’s misfortunes.

Most of the film takes place in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Bahrani’s hometown, with many moody, atmospheric shots of the cityscape at night. One crucial scene involves a drive into the woods and mountains, however, and much of it is filmed in a dense fog. One questioner from the audience asked if Bahrani had planned to shoot in such weather or if, given his short shooting schedule, the fog turned out to be a hindrance to him. He responded that he had dreamed of being able to shoot in fog and that the weather cooperated on the three days planned for that locale. In fact, he re-shot some images as the fog became denser, to keep the scene fairly consistent.

Bahrani’s presence at Ebertfest spans half its existence, from 2006 to 2014. As the festival becomes more diverse in its offerings, it is good to have him back as a reminder of the Ebertfest’s early emphasis on the “overlooked.”

Of Paramount importance

Logo for National Telefilm Associates, TV syndication arm of Republic Pictures.

DB here:

Among the guests at this year’s E-fest was Barry C. Allen. For over a decade Barry was Executive Director of Film Preservation and Archival Resources for Paramount. That meant that he had to find, protect, and preserve the film and television assets of the company—including not just the Paramount-labeled product but libraries that Paramount acquired. Most notable among the latter was the Republic Pictures collection.

We may think of Republic as primarily a B studio, but it produced several significant films in the 1940s and 1950s—The Red Pony, The Great Flammarion, Macbeth, Moonrise, and Johnny Guitar. John Wayne became the most famous Republic star in films like Dark Command, Angel and the Badman, and Sands of Iwo Jima. John Ford’s The Quiet Man was Wayne’s last for the studio, which folded in 1959. Next time you see one of the gorgeous prints or digital copies of that classic, thank Barry for his deep background work that underlies the ongoing work of his dedicated colleagues.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Hard as it may seem for young people today to believe, in the 1950s TV stations routinely cut the films they showed. Packages of 16mm prints circulated to local stations, and these showings were sponsored by local businesses. Commercials had to be inserted (usually eight per show), and the films had to be fitted to specific lengths.

WISH-TV ran three movies a day, and two of those would be trimmed to 90-minute air slots. That meant reducing the film, regardless of length, to 67-68 minutes. Barry’s job was to look for scenes to omit—usually the opening portions—and smoothly remove them. Fortunately for purists, the late movie, running at 11:30, was usually shown uncut, and then the station would sign off.

By coincidence I recently saw a TV print of Union Depot (Warners, 1932) that had several minutes of the opening exposition lopped off. We who have Turner Classic Movies don’t realize how lucky we are. Fortunately for film collectors, some stations, like Barry’s, retained the trims and put them back into the prints.

While working at WISH-TV, Barry began booking films part-time. He programmed some art cinemas in the Indianapolis area during the early 1970s, mixing classic fare (Marx Brothers), current cult movies (Night of the Living Dead), and arthouse releases like Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie—a bigger hit than anyone had anticipated. He also helped arrange a visit of Gloria Swanson with Queen Kelly; she carried the nitrate reels in her baggage.

At the same time, Barry was learning the new world of video editing, with ¾” tape and telecine. Because of his experience in television, Barry was contacted by Paramount to become Director of Domestic Syndication Operations. His chief duty was to deliver films to TV stations via tape, satellite, and prints. From that position, he moved to the preservation role he held until 2010, when he retired.

Barry is a true film fan. He has reread Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By many times and retains his love for classic cinema. The film that converted him to foreign-language cinema was, as for many of his generation, Children of Paradise, but he retains a fondness for Juliet of the Spirits, The Lady Killers, and other mainstays of the arthouse circuit of his (and my) day. He’s proudest of his work preserving John Wayne’s pre-Stagecoach films.

It was a great pleasure to hang out with Barry at Ebertfest. Talking with him reminded me that The Industry has long housed many sophisticated intellectuals and cinephiles. Not every suit is a crass bureaucrat.

Young-ish adult

Patton Oswalt had planned to come to Ebertfest in an earlier year, to accompany Big Fan and to show Kind Hearts and Coronets to an undergrad audience. He had to withdraw, but he showed up this year. On Wednesday night he screened The Taking of Pelham 123 to an enthusiastic campus crowd, and the following night, after getting his Golden Thumb, he talked about Young Adult. (Roger’s review is here.)

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

It’s common for viewers to notice that Mavis Gary, the malevolent, disturbed main character of Young Adult, doesn’t change or learn. “Anti-arc and anti-growth,” Oswalt called the movie. I found the film intriguing because structurally, it seems to be that rare romantic comedy centered on the antagonist.

Mavis returns to her home town to seduce her old boyfriend, who’s now a happy husband and father. A more conventional plot would be organized around Buddy and his family. In that version we’d share their perspective on the action and we’d see Mavis as a disruptive force menacing their happiness.

What screenwriter Diablo Cody has done, I think, is built the film around what most plots would consider the villain. So it’s not surprising that there’s no change; villains often persist in their wickedness to the point of death. Attaching our viewpoint to the traditional antagonist not only creates new comic possibilities, mostly based on Mavis’s growing desperation and her obliviousness to her social gaffes. The movie comes off as more sour and outrageous than it would if Buddy and Beth had been the center of the plot.

Making us side with the villain also allows Oswalt, as Matt Freehauf, to play a more active role as Mavis’s counselor. In a more traditional film, he’d probably be rewritten to be a friend of Buddy’s. Here he’s the wisecracking voice of sanity, reminding Mavis of her selfishness while still being enough in thrall to high-school values to find her fascinating. As in Shakespearean comedy, though, the spoiler is expelled from the green world that she threatens. It’s just that here, we go in and out of it with her and see that her illusions remain intact. Maybe we also share her sense that the good people can be fairly boring.

All you can eat

There aren’t any villains in Ann Hui’s A Simple Life, a film we first saw in Vancouver back in 2011. Roger had hoped to bring it last year, but Ann couldn’t come, as she was working on her upcoming release, The Golden Era. This year she was free to accompany the film that had a special meaning for Roger at that point in his life.

The quietness of the film is exemplary. It’s an effort to make a drama out of everyday happenings—people working, eating, sharing a home, getting sick, worrying about money, helping friends, and all the other stuff that fills most of our time. The two central characters are, as Roger’s review puts it, “two inward people” who are simple and decent. Yet Ann’s script and direction, and the playing of Deanie Yip Tak-han and Andy Lau Tak-wah, give us a full-length portrait of a relationship in which each depends on the other.

Roger Leung takes Ah-Tao, his amah, or all-purpose servant, pretty much for granted. She feeds him, watches out for his health, cleans the apartment, even packs for his business trips. When he’s not loping to and from his film shoot, he’s impassively chowing down her cooking and staring at the TV. A sudden stroke incapacitates her, and now comes the first surprise. A conventional plot would show her resisting being sent to a nursing home, but she insists on going. Having worked for Roger’s family for sixty years, Ah-Tao can’t accept being waited upon in the apartment. So she moves to a home, where most of the film takes place.

A Simple Life resists the chance to play up dramas in the facility. Thanks to a mixture of amateur actors and non-actors, the film has a documentary quality. It captures in a matter-of-fact way the grim side of the place—slack jaws, staring eyes, pervasive smells. (A small touch: Ah-Tao stuffs tissue into her nostrils when she heads to the toilet.) Mostly, however, we get a sense of the facility’s everyday routines as the seasons change. The dramas are minuscule. Occasionally the old folks snap at one another, and one visitor gets testy with her mother-in-law. One woman dies (in a bit of cinematic trickery, Ann suggests that it’s Ah-Tao), and an old man who keeps borrowing money is revealed to have a bit of a secret. It’s suggested that a pleasant young woman working at the care facility will become Roger’s new amah, but that seems not to happen. The prospect of a romance with her is evoked only to be dispelled.

Ah-Tao’s health crisis has made Roger more self-reliant, but his life has become much emptier. He seems to realize this in a late scene, when he stands in the hospital deciding how to handle Ah-Tao’s final illness. Throughout the film, food has been a multifaceted image of caring, community, friendship, childhood (Roger’s friends recall Ah-Tao cooking for them), and even the afterlife. Ah-Tao and Roger rewrite the Ecclesiastes line about what’s proper to every season by filling in favorite dishes. As he mulls over Ah-Tao’s fate, Roger is, of course, eating. But it’s cheap takeaway noodles and soda pop. This silent scene measures his, and her, loss better than any dialogue could.

The art of American agitprop

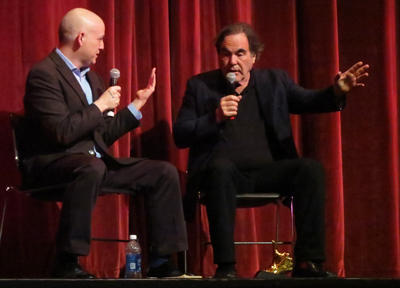

Matt Zoller Seitz and Oliver Stone on stage at the Virginia Theatre.

A Simple Life is a very quiet film. Ebertfest’s highest-profile visitors brought along two of the noisiest movies of 1989. It’s the twenty-fifth anniversary of Do The Right Thing (Roger’s review) and Born on the Fourth of July (Roger’s review), and seen in successive nights they seemed to me to put the “agitation” into agitprop.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.