Archive for 2014

Pulverizing plots: Into the woods with Sondheim, Shklovsky, and David O. Russell

American Hustle (2013).

The different writers, who live in different times, come across the same pattern, the same chain of circumstances, which reveal themselves in different ways in each time.

This is how plot travels through time.

Viktor Shkovsky, 1981

DB here:

Besides writing some fine tunes and cunning rhymes, Stephen Sondheim has been an audacious experimenter with storytelling on stage. Do you know Into the Woods? It’s a bittersweet mashup of fairytales. Instead of presenting each one separately, like the vignettes of Japanese history in Pacific Overtures, here Sondheim’s collaborator James Lapine has woven them into one elaborate super-story. Rapunzel turns out to be the sister of the baker who sells bread to Red Riding Hood to take to Grandma. The princes pursuing Cinderella and Rapunzel are brothers who eventually turn their affections to Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. And so on. It’s an ingenious contraption, and I look forward to the film version to be released this year.

Even before that, we can learn something useful from what Sondheim has done. In effect, he has offered us a nifty audiovisual aid for understanding some ideas about storytelling advanced by the Russian Viktor Shklovsky. Shklovsky is surely the most eccentric literary critic of the twentieth century. He is also one of the greatest.

Thanks to Maria Belodubrovskaya and web tsarina Meg Hamel, we’ve just posted the first English translation of a rare Shklovsky essay elsewhere on this site. Today I want to consider a couple of Shklovsky’s many provocative ideas.

All the reverses

Shklovsky wasn’t an ivory-tower aesthete. He fought in World War I, joined the 1917 February Revolution that overthrew the Tsar, and continued an army career. As a Social Revolutionary, he initially opposed the Bolsheviks and spent several years in hiding and in exile in Germany. In 1923 he returned to the USSR and settled in to work as a professional writer.

Abandoning university life (he never took his exams), he wrote countless journalistic essays and several film scripts for Soviet classics: By the Law (1926), Bed and Sofa (1927), The House on Trubnaya Square (1928), and the documentary Turksib (1929). His novels were experimental efforts, mixing memoirs with speculations on literature. Zoo, or Letters Not About Love (1923) subverts the form of the epistolary novel by including letters that are not to be read. (A red X crosses them out.)

Abandoning university life (he never took his exams), he wrote countless journalistic essays and several film scripts for Soviet classics: By the Law (1926), Bed and Sofa (1927), The House on Trubnaya Square (1928), and the documentary Turksib (1929). His novels were experimental efforts, mixing memoirs with speculations on literature. Zoo, or Letters Not About Love (1923) subverts the form of the epistolary novel by including letters that are not to be read. (A red X crosses them out.)

He became known for a porous, cryptic approach to writing. He can be repetitious, puzzling, tedious, and maddening; outlining one of his essays is a wrestling match. His jittery style mobilizes brief paragraphs, some consisting of a single short sentence, much as Eisenstein and other directors used short film shots: as a percussive device to assail the reader.

A quick phrase can swing into a digression, a tactic Shklovsky relied on even more as he advanced into his eighties. The man who thought Tristram Shandy was “the most typical novel in literature” had a soft spot for delay and detour. Some variations:

To take a break, I am inserting here a page from one of my old manuscripts.

After such an opening, one can digress in any direction.

Being the theorist of “baring the device,” Shklovsky naturally accentuates the artifice of his technique. “It’s not easy to enact a change of theme,” he says, doing it while talking about it. Later we get a hint of the arbitrariness of organization. “I’ll repeat–continuity can be started from any place.”

Shklovsky’s most enduring fame came through his association with what has become known as Russian Formalism. While studying at St. Petersburg, Shklovsky and some friends formed OPOYAZ, the “Society for the Study of Poetic Language.” They were convinced that the literary history they were being taught failed to get at the essence of “literariness”—the specific quality that made literature a distinct domain. Historians could compile names and dates, speculate on biographical influences and social pressures, but this still wouldn’t distinguish literary forms from non-literary ones. What makes a poem different from a grocery list, a courtroom drama different from a trial transcript?

In the late teens and early twenties, Shklovsky and his colleagues set forth a new approach to literature. That approach was called, by its enemies, “Formalism,” and the name has stuck.

In English, of course, the word has so many meanings that it should probably be retired. Sometimes it means studying “form” and neglecting “content”; that was part of what the Stalinist hacks meant when they insisted that Shklovsky & Co. weren’t advancing the class struggle by emphasizing ideology. Today, to use “formalism” as a slam is often to suggest something similar—that a formalist ignores “content” like race, class, gender, and nation. But the Formalists didn’t neglect content. What others considered content they treated as material that is shaped by the literary work.

Following up Formalist theory fully would take me far afield. Instead, I want to turn to Shklovsky for some thoughts on plot structure that are fairly different from those I floated here a little while ago. Consider it a fuller test drive than my entry from a while back discussing how Shklovskian theory helps us understand the evolution of John le Carré’s career.

Once upon a time

The Formalists were among the founders of “narratology,” the systematic study of storytelling. They gave us the foundational distinction between story and plot, or fabula and syuzhet. The fabula consists of the events in the story world as they’re arranged according to time, space, and causality. The syuzhet consists of the story events as we encounter them in the finished narrative. Flashbacks furnish the most obvious example of how plot structure rearranges story order. Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along is more unusual: its plot presents its story episodes in reverse order, so that the last thing we see is the earliest scene in the fabula.

My essay, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” and the accompanying blog post on The Wolf of Wall Street, reflected my basic take on narrative analysis, which is holistic. I try to get a sense of the overall architecture, and see how particular elements slot into that. For instance, by suggesting that The Wolf has a five-part act structure, I traced a development from part to part as Jordan sets up his trading firm, conducts an affair that destroys his marriage, launches an IPO and attracts the attention of the Feds, expands his scheme to offshore money laundering, and eventually comes to ruin….and resurrection. My analysis traced action patterns that unfold like musical melodies through the movie.

Most people would defend a holistic approach in another way. The Wolf of Wall Street runs 173 minutes without credits. Its admirers argue that it needs to be so long because it has to accommodate all the plots and counterplots. True, maybe some scenes are a bit stretched (notably Jordan’s and Donnie’s hilarious Quaalude orgy), but on the whole Scorsese and his screenwriter Terence Winter could say that telling Jordan’s story adequately demanded a long running time.

Shklovsky asks us to think of storytelling less holistically, or at least to think of a different sort of whole. He takes us through the looking glass.

*Instead of treating a narrative as a linear chain of events—say, the adventures of an egoist like Jordan—let’s think of it as a point of intersection of various materials. Not a linear flow, but a collage of items brought in, trimmed, or discarded as needed.

*And instead of taking a narrative as determining the time it takes to unfold, let’s think of the time as determining the narrative. Think of the narrative as built to scale, with a predetermined size into which material has to be fitted.

Every knot was once straight rope

The Decameron (1971).

Shklovsky thinks that a narrative is like a collage because historically, short narratives aren’t cut-down long ones. Instead, long texts have been woven out of short ones. He and his colleagues were much influenced by studies in folklore, which showed that folktales were often built out of familiar pieces, or motifs. A motif might be a character, such as a jealous stepmother; an object, such as a magical ring; or an action, such as a test or competition. Storytellers could combine these motifs to create their plots. This is, on a big and self-conscious scale, what Sondheim has done in Into the Woods.

Shklovsky extends the idea of motif-assembly to the novel, which he claims grew out of collections of shorter stories. One example is The Golden Ass, an ancient Latin novel of the first or second century AD. In this tale a traveler undergoes some adventures but he also encounters characters who tell him their own stories. (Some of those may be based on folktales.) Similarly, the fourteenth-century Decameron of Boccacio consists of tales exchanged among ten characters sequestered to escape a plague in their city.

We have such story-collections in cinema, though they’re not common. Most obviously, Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life” (The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, The Arabian Nights) drew upon the tradition that Shklovsky is charting. A Hollywood example would be O. Henry’s Full House (1952).

Finding a pretext for assembling stories exemplifies what OPOYAZ called motivation. Motivation, as I’ve discussed here before, involves creating a justification for a formal choice. Motivation isn’t just for actors who figure out why a character behaves a certain way. It’s for every artist, as when a cinematographer tells of needing to “motivate” a pattern of light by providing a lamp or window.

More broadly, motivation gives the audience a reason to accept a formal option. One of my favorite examples comes in Citizen Kane. Having decided to tell Kane’s story in flashbacks more or less chronologically, Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles confronted a problem in their frame story. After Kane’s death a reporter would naturally turn to his surviving second wife before contacting friends or associates. But if Susan recounted her memories of Kane before the other witnesses did, her episodes would come from late in his life and throw off the chronology. Therefore the script makes Susan too drunk and angry to talk to the reporter Thompson when he calls. He must proceed to the Thatcher library, where he’ll learn about Kane’s earliest years. Later, when Susan is more sober, she recounts her flashback in its proper, chronological place.

Motivation is everywhere in cinema, and it assumes different guises. Sometimes filmmakers motivate their choices by realism. Susan, being an alcoholic, might well angrily refuse to talk to the reporter. Filmmakers also appeal to genre-driven factors, as when people sing and dance in a musical; presumably this will be the rationale for the musical numbers in the movie of Into the Woods, as they are in the play. Very often the motivation springs from what the plot demands. In a mystery, to keep viewers in the dark, you can attach the action to an investigator who gradually discovers what’s really going on.

Sometimes style needs motivation. In the recent vogue for first-person films like End of Watch, Chronicle, and the Paranormal Activity series, the makers find excuses for the characters to use their video cameras to record what’s happening.

Foreshadowing is a sort of motivation too. In The Wolf of Wall Street, Naomi’s aunt Emma comes to the couple’s wedding. In realistic terms, inviting a relative to the ceremony is plausible, but it’s there for structural reasons. The plot needs to introduce a character living overseas whom Jordan can later use to hold his smuggled money. This might seem a cold-hearted way to view a character, but the plot treats her just as heartlessly, killing her off at just the moment that precipitates a climax.

In sum, Shklovsky’s engineering approach prods us to ask why something is in this tale—not according to character psychology or thematic statement, but as part of a system of materials and their motivations. Perhaps Shklovsky thought he could motivate his late-period digressions by the reader’s knowledge of his age: the Grandpa Simpson alibi.

I’m in the wrong story

Wine of Youth (1924) publicity still.

How to motivate the sort of story-collections we started with? Minimally, you can create a framing situation in which one or more persons share a tale with an audience; that’s the Decameron solution. You can go further by making the tales seem to belong together. Perhaps they parallel one another, either explicitly or implicitly. One might prove that crime doesn’t pay, while another disproves it. Shklovsky calls this “a debate of stories.” In the 1924 film Wine of Youth, a young woman hears from her mother and grandmother about their courtships. The similarities and differences across the generations create comic parallels to the young woman’s own romance.

You could also motivate the connection between the frame story and the embedded ones. Shklovsky mentions that the very act of telling can slow down the action in the frame story, as when Scheherazade keeps narrating every night to postpone her death. Or perhaps a discovered manuscript (the embedded story) will have an impact on the people finding it. You might try to somehow blend the told story with the act of storytelling. In the British film Dead of Night (1945) the separate stories all involve fantastic events, and the people telling the tales stand outside them. But the film’s climax seems to turn the frame story itself into such a fantasy, creating a sort of Mobius strip that twists the film back to its beginning.

I think, though, the greatest power of Shklovsky’s idea comes with the notion that any big narrative is really composed of smaller ones. He goes beyond episodic assemblies like The Decameron and Dead of Night to suggest that even the most “organic” or tightly-designed plots can be considered well-disguised story collections. In other words, my holistic assumption is countered by one that treats a well-shaped whole as a heavily motivated collage of different stories. From Shklovsky’s perspective every narrative of any complexity is like Into the Woods.

We can imagine a continuum of the ways in which fairly distinct story lines are woven into one big one. You might bring the characters together in a single space, such as an inn. Cervantes used this tactic in Don Quixote, and the great Chinese filmmaker King Hu revived it in several of his films. Grand Hotel, Hotel Berlin, The VIPs, Nashville, and many other ensemble films gather different story lines within a single space and let them intertwine. Sondheim and Lapine brought their fairy-tale plots together in the same locale, the primeval woods. Often the linkage is one of time as well, with the action compressed into a few hours or days.

Given a unity of time and locale, we expect that the story lines will affect one another, which indeed happens in the films I’ve mentioned. This puts us in the land of what I’ve called “network narratives” and what Peter Parshall studies in his book Altman and After.

Apart from spatial connections and concentrated time connections, you can hook up your source-stories more tightly. Most complex narratives assign the characters roles in different story lines. For instance, Into the Woods ties its fairy-tale figures together by friendship, acquaintance, love, and kinship. Characters create goals that involve other characters. Rapunzel’s mother the witch demands ingredients for a potion, and these bring in Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Cinderella.

The implication is that every plot of any complexity, no matter how smoothly all its parts seem to fit together, is a paste-up, a virtual recombination of simpler action lines sewn together by motivations. A romantic comedy with a main couple and a secondary one? It’s essentially two separate plots joined by the simple strategy of making the couples friends with each other. The detective story in which various characters tell us their alibis? Separate plots hooked up by the need to involve them in the murder investigation. The heist movie that follows all the characters partnering in a single robbery? It compiles plots about different thieves and welds them together by a shared knockover.

Any path . . . so many worth exploring

For Shklovsky, even a novel’s protagonist can serve as a motivating device for connecting the various stories he or she encounters. “Gil Blas is not a human being at all. He is a thread, a tedious thread, by means of which all the episodes of the novel are woven together.” Likewise, in The Wolf of Wall Street, Jordan is not given a lot of depth. Some viewers have criticized this tactic, since he doesn’t change his attitude or ethical outlook, and seems to learn nothing from his rise and fall. Shklovsky could suggest that he’s chiefly a device for hooking together a string of episodes about the giddy high life of stock trading. Showing a weasel behaving like a weasel for three hours—some viewers have found him indeed “a tedious thread”—isn’t especially edifying in itself, but the film’s fascination comes chiefly from the escalation of excess we’re invited to witness.

From this angle, The Wolf of Wall Street somewhat resembles another current release, The Great Beauty. This film is more explicit in using the protagonist to combine plots that represent a cross-section of a society. We’ve had other films that use one character to survey, fresco-fashion, different milieus. Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu is one such plot, and La Dolce Vita, to which The Great Beauty has often been compared, is another. Usually, though, the protagonist responds to what she or he encounters and changes as a result; in The Great Beauty Jep’s wanderings create a sort of ephiphany. Perhaps the novelty of the plot of The Wolf of Wall Street is that after being introduced to high-flying hedonism Jordan rushes in and never looks back.

Of course we could imagine other versions of The Wolf—an apprentice plot showing us Jordan learning the ropes at length from Mark Hanna, or a multiple-protagonist plot in which Donnie, Teresa, Naomi, and other characters get much more attention. Shklovsky reminds us of what screenwriters know instinctively: plot unity is often a matter of ruthlessly chopping out all those intriguing alternatives. Every complex tale is yanked and snipped out of a vast network of potential plots.

Consider American Hustle, much more of an ensemble piece than The Wolf. (Spoilers ahead.) I see it as a romantic comedy with a crime ingredient. Three principal love triangles are interlocked (Irving-Sydney-Rosalyn, Irving-Sidney-Richie, Irving-Rosalyn-Pete). These are pushed forward thanks to the doubled plotline characteristic of classical Hollywood cinema: work and love so intertwine so that the sting operation develops along with the romantic complications. David O. Russell and co-screenwriter Eric Warren Singer use many well-practiced comic conventions, including overheard conversations that precipitate crises. (As usual, no coincidence, no story.) In its unfolding American Hustle fits Kristin’s four-part-plus-epilogue model tidily.

In contrast to my perspective, Shklovsky invites us to consider how several conventional plots are squeezed into Russell’s film. Here are some.

*A husband has an affair with another woman, and his wife learns of it.

*A woman is a man’s mistress but another man is attracted to her. She leads both of them on.

*A con artist fleeces gullible people with the aid of a confederate.

*A dutiful father tries to protect his son from the mother, who’s a little crazy.

*A man betrays his friend and feels the need to confess it, even though it will ruin their friendship.

*A cop tries to bring down big-time crooks, against the wishes of his supervisor.

*A cop has captured a crook and wants to use that crook to get to higher-ups.

*A wife, feeling ignored by her husband, seeks the attention of other men.

*A man has a fiancée approved by his mother, but he’s attracted to a more glamorous woman.

*A small-time crook tries to scam the Mafia, and the gangsters learn of it.

*A father warns his sons against fishing on thin ice.

These plots are blended by having a few characters play multiple roles in them. Even in this profusion, by rewriting the film we could go further—say, expanding the conflict between the cop Richie and his mother, or going back further into Sydney’s past. As with The Wolf, by developing the sub-stories, we could multiply story threads forever.

Narrative can flourish like kudzu. What curtails things? Among other things, the second factor I mentioned at the outset: format.

Slotted spoons don’t hold much soup

Shklovsky suggests that very often a story is created (or re-created) in order to be of a certain size. Instead of the old saw “form follows function,” Shkovsky suggests another: form follows format. The length of the narrative is dictated in large part by the sort of thing it’s going to be. A pop song isn’t an operetta, a short story isn’t a novel, a miniature isn’t a mural.

At first glance this notion seems too stringent. Surely a poem or play can be any length we want. There are gigantic symphonies and sprawling picture scrolls. Whitman seems to have had no problem adding more and more poetry to editions of Leaves of Grass. But these instances might be exceptional.

There will always be outliers, especially among the avant-garde, but most storytellers work in media that set limits and favor certain lengths. At the moment, three hours is sort of a maximum for a Broadway musical play like Wicked, The Book of Mormon, or Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. It makes sense that, given high ticket prices, audiences want a reasonably extended experience. They get one in Into the Woods: it standardly runs about three hours, including intermission.

Even a big name like Sondheim works within time constraints. When he and James Lapine were contemplating redoing a fairy tale, they made a discovery.

Fairy tales, by nature, are short; the plots turn on a dime, there are few characters and even fewer complications. This problem is best demonstrated by every fairy-tale movie and TV show since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, all of which pad the lean stories with songs and side-kicks and subplots, some of which are more involving than the interrupted story itself. And those are all less than two hours long.

They needed to expand their material to Broadway length, and they did it by recalling an idea they’d concocted long before—a TV show that brought together characters from other TV shows.

Shklovsky’s suggestion is particularly attractive to those of us who study media because most artworks in commercial formats fit basic dictates of size. . US network TV episodes run 22 minutes or 45 minutes. Novels have roomier boundaries, but editors still have their preferences. According to a publisher’s marketer, in 2010 the ideal novel ran between 80,000 and 110,000 words. The doorstops bestowed on us by Rowling, Martin, and Stephen King are the market-tested, lucrative exceptions.

As for films, we still have pretty strong constraints outside avant-garde and festival pieces like Sátántangó (seven hours). A-level feature films in the 1940s typically ran between 80 and 120 minutes; B-films were typically 60 to 80 minutes. The longest running times were reserved for roadshow specials like Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun. I don’t know of a systematic study of changes in running times, but today there’s still apparently a two-tiered system. Program pictures (horror, action, raunchy comedy) with unknowns or minor stars (e.g., Jason Statham) can run around 85-100 minutes, with credits. The big releases can run two hours or more, but seldom more than three. When asked why originally The Grandmaster was 130 minutes, Wong Kar-wai is said to have replied, “All movies are 130 minutes now.”

Granted, directors’ cuts and alternative editions offer some flexibility. An initial four-hour cut of The Wolf of Wall Street had to be chopped down to a little less than three, but the long version may show up on disc or VOD. For all I know, it could become a mini-series. But even then its installments will be constrained by the running times of that format. And my other main example today, American Hustle, fits Wong’s point: Without credits, it runs 130:30.

Only three more tries

Lion King 1 1/2 (2004).

How is the format’s scale connected to Shklovsky’s idea about building your narrative out of pieces? This way: You find or create the pieces that will fill out the narrative to a conventional size. The format helps you decide how much to add or take away from the ongoing collage you’re creating of characters, actions, and story lines. Again it’s a matter of motivation, finding ways of justifying what you want to keep in or leave out.

Within the overall size of the piece, there are smaller chunks that need to be filled. A recent example is Anchorman 2.5, in which new gags replace old ones but still must be squeezed into the original scenes. Today’s screenwriting manuals, with their insistence on something big happening on certain pages, also indicate how storytellers are encouraged to invent material to be fitted into a fixed frame. Some people hate the idea of a “formulaic” screenplay, but Shklovsky the pragmatist would, I think, compare it to verse forms like the sonnet and the haiku, which dictate quite specific slots to be filled. In this respect, Kristin’s multi-part model of mainstream feature films is compatible with Shklovsky’s idea: She has made the format’s customary subdivisions explicit.

Very often, you may need to stretch out a story situation to fit the time allotted. To some extent, folding several mini-plots into your big plot gives you the chance to extend the whole thing. In particular, often the plots don’t blend but actually block one another. In American Hustle, Rosalyn’s jealous-wife storyline serves to prolong the action around Irving and Richie’s scam, especially when she starts flirting with the casino magnates at the big dinner. Similarly, Richie’s escalating schemes to go after bigger crooks keeps thwarting Irving’s plan to mount simple scams that will let him and Sydney skate.

What to do when you lack material? We have some historical examples. In cinema, Griffith found several ways to fill out the one- and two-reel formats. Instead of simply showing characters coming into a scene, he filmed simple, mostly undramatic “goings and comings” that followed characters leaving one spot, traveling, and arriving at another spot. He also discovered that he could stretch out a situation by crosscutting two simultaneous actions.

An Aristotelian could say that Griffith discovered that crosscutting could generate suspense in rescue situations, but Shklovsky starts from sheer delay as an engineering principle. Why do the villains in such situations take such an ungodly time to accomplish their villainy? In 1923, Shklovsky recognized the emerging conventions of action cinema, still going strong today.

Attempted rape in a modern film is almost canonized. The victim is struggling, her friends are far away, the villain is pursuing the woman, “meanwhile,” etc. In my opinion, the choice of the crime in this instance is explained not so much by the desire to play on the spectator’s interest in eroticism as by the actual nature of the crime, which requires for its completion a certain amount of time. Instead of rape, take murder by pistol shot. Such an act is too indivisible. That is why cinematic villainy is usually perpetrated by a method that requires a large amount of time—drowning, for example, with the victim suspended upside down in a cellar and water pouring in. Sometimes the victim is bound hand and foot, then tossed on the railroad tracks, or else immured. Also effective is abduction in all its varieties. Only minor characters, not involved in the plot, are killed off immediately.

He might have added that the hero may be given a weak friend, whose death can be a little more protracted (and motivate the hero’s quest for revenge).

We tend to think of delay as padding, but actually narratives need it. Delay can be unmotivated, as digressions are. More often it’s motivated. In folk tales, why does the hero have two brothers? So that they can try and fail at the task that he will accomplish. (Hollywood’s rule of three may have its roots in folklore.) Stretching out the intervals between major plot points allows other things to be inserted—gags, character exposition, musical numbers, witty dialogue. Tarantino is very accomplished at dialogue-driven retardation. Call it the Royale-with-Cheese tactic.

It sounds strange to think of a novel’s descriptions of what characters eat and wear and drive as filler material. Ditto weather reports and portraits of neighborhoods. But Shklovsky suggests that in most cases that’s what these portions are, more or less motivated bits that flesh out the plot and connect the bits that the story-maker has brought on for this occasion. They can be further elaborated to create motifs and bind the work more firmly.

It seems even stranger that the same purposes of filling out the format and delaying the main events should be fulfilled by character traits. We tend to think of characters as modeled on living people—simpler, but with recognizable traits, habits, temperaments, and the like. For Shklovsky, a character can be minimal or maximal, depending on how much time or pages you have to fill. If your plot material is thin, you can thicken it by expanding your character, and at some point you have a psychological novel.

In some cases, by searching for material to expand the tale, the artist discovers new depths in his characters, as Shklovsky thinks Cervantes did with Don Quixote. The Don, initially a compilation of clichés drawn from chivalric romances, becomes richer as the first book proceeds. By the second book there’s a new self-consciousness about Quixote and Sancho, who are now famous to the other characters as heroes of the first book. You might think of The Godfather Part II or the sequels to Back to the Future when Shklovsky notes that the sequels to novels often change their structure radically, taking the original as a pretext for other explorations. The ill-remembered Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 (2000) and the more ingratiating Lion King 1 ½ (2004) use the Quixote device of building a sequel around characters who know the first installment.

Similarly, characterization serves to freshen up the familiar plot ingredients in American Hustle. Irving isn’t a slick con artist but rather a passable klutz who needs the social grace injected by Sydney. Richie isn’t your usual cop on a mission but a working-class guy burning with ambition, and this leads him to expand the scam to a level he can’t handle. Rosalyn is the slightly batty wife who’s expert in passive-aggressive combat. I suspect that what a lot of audiences enjoy about the film is the way several conventional characters are given vigorous detailing by the writing and the performances.

Happy ever after

The act of combining and fitting stories to a format demands that the storyteller find an ending. Shklovsky doesn’t have a lot of respect for endings. Given that making and motivating a plot are fairly arbitrary, the wrapup is likely to seem even more so. Shklovsky says that Thackeray wished he could order his servants to compose the endings of his novels.

Part of the problem is that while beginnings and middles bristle with surprises, resolutions are fairly routine. There’s the tragic ending, in which the hero dies. Another option is the ABA pattern, or “Here we go again.” In The Wolf of Wall Street, Jordan starts over, selling not stocks but the very idea of selling. Something similar seems to happen at the close of Into the Woods. The main action springs from people yearning for more than they have, given in the opening number, “I Wish.” After all the mishaps and deaths, the characters seem to settle for what happiness they have. Hence the bustling closing number, “Into the woods…and happy ever after.” But just as that song resolves and closure seems complete, Cinderella pipes up with “I wish….” Here we go again.

Then there is what Shklovsky calls the “incomplete” ending, the sort of open structure that doesn’t fully tell us how things work out. Chekhov and Maupassant are Shklovsky’s examples. In such instances, he points out, our cue for conclusion is often a description of the setting or the weather. In a way, these inconclusive endings acknowledge a fact of art: all endings are equally conventional, pieces of high artifice. None captures real life, which is absolutely endless in a way a text can’t be. Individuals die, but human life continues, and fate is essentially indefinite.

Shklovsky realizes, however, that readers favor the happy ending. Lovers are united, usually by marriage, or the adventurer returns safely from peril (the end of Jaws). American Hustle, being at bottom a romantic comedy, concludes with the main couple back together and successful in their art business. There’s also the formation of a secondary couple, Rosalyn and the mobster Pete. The pay-to-play mayor, who wants genuinely to help his city, gets mildly punished, while the real loser is the cop Richie. He becomes the expelled lover in the Ralph Bellamy tradition.

I think that Shklovsky would enjoy the film’s self-consciousness about its neat wrapup. American Hustle parodies the model of the incomplete ending. We never learn the outcome, or the point, of Stoddard’s childhood memory of ice-fishing. And the film’s final line, heard in Irving’s voice-over, ties his forged-painting scam to the overall dynamics of the plot: “The art of survival is a story that never ends.”

By tracing the activity of linking materials and filling the format, Shklovsky isn’t, I think, trying to describe every storyteller’s creative process. Many writers simply pour the stuff out. What I think he’s proposing are the principles behind the process. A practiced writer does all this intuitively. I once asked Elmore Leonard if he planned the very long dialogue scene that runs for several chapters in Get Shorty. He said, “It just came out that way.” But I notice that without that long section, the book would be severely out of balance—and too short. It’s a virtuoso cadenza, at once pure retardation and a package of motifs that point both forward and backward in the plot.

We’re now quite at home with films that intertwine storylines, restart storylines (Groundhog Day, The Butterfly Effect, Source Code), present branching and forking-path storylines (Run Lola Run, The Girl Who Leaped through Time), or simply set barely connected stories side by side (Chungking Express, Flirt, Nine Lives). So we should be ready to see more traditional plots as heavily camouflaged attempts at combining smaller stories. We should likewise be ready to see how stronger or lesser motivation governs all the options. Source Code relies on a science-fiction premise and a thriller deadline, while Groundhog Day motivates its replays and variations by setting its action on the one day that posits that the future will turn out either this way or that way.

For my part, I confess myself both an Aristotelian and a Shklovskian. I think that we ought to look for a plot’s structural unity at many levels. I think as well that those levels may incorporate the most wayward materials. The pieces are pulled into place and held there, sometimes precariously, by the scale of the format, their local purposes, and the motivational pressure of other components. Vincent Vega’s Royale-with-cheese exposition does hook up with the Big Cahuna burger we encounter later.

And both approaches provide useful critical tools. Seeing Jordan as a pretext for a dissection of his Wall Street world opens up certain aspects of the film that might not be apparent if we kept expecting him to follow a learning curve. By seeing how American Hustle braids together many standard plot patterns, we can explain how the film can juggle its situations with such speed and how we can look forward to seeing certain patterns fulfilled (or not). Studying narrative from either a holistic or a “montage” perspective can only enhance our appreciation of all the different kinds of stories we encounter.

To save you scrolling back up, here is another link to Shklovsky’s “Monument to a Scientific Error,” posted in the Essays section of this site.

This entry’s primary accounts of Shklovsky’s thinking on narrative are drawn from his essays “The Structure of Fiction” of 1925 and “The Making of Don Quixote” of 1921. Both are included in his landmark book Theory of Prose, originally published in 1925 and available in translation from the ever-vigilant Dalkey Archive. Shklovsky talks about the distinction between form and material in the early chapters of the 1923 book Literature and Cinematography, trans. Irene Masinovsky (Champaign: Dalkey Archive, 2008); my quotation about villainy is drawn from p. 60. Other references are from the 1981 Energy of Delusion: A Book on Plot, trans. Shushan Avagyan (Champaign: Dalkey Archive, 2007).

French Structuralism borrowed considerably from the OPOYAZ school. Roland Barthes launched his own version of Shklovsky’s retardation thesis in both his “Structural Analysis of Narratives” essay (the distinction between kernel actions and satellites) and his S/Z (the distinction between the proairetic code and the semic code). For his part, Shklovsky was skeptical about Structuralism, not least because of its vocabulary. “People today get carried away with terminology; there are so many terms that it’s impossible to learn them all, even if you’re a young person on vacation” (Energy of Delusion, 177).

My quotation from Sondheim about the construction of Into the Woods comes from Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany (Knopf, 2011), p. 57.

For more on how the split-roads motif of folklore persists in modern storytelling, see this earlier entry. I consider how embedded stories and framing situations can tax our memories in this entry. The multiple-drafts plot of Source Code is considered here, while various motivations for first-person video style are explored in these pieces on Cloverfield and the Paranormal Activity cycle.

Into the Woods cast, San Mateo High School production of May 2006.

James Agee: All there and primed to go off

Monsieur Verdoux (1947).

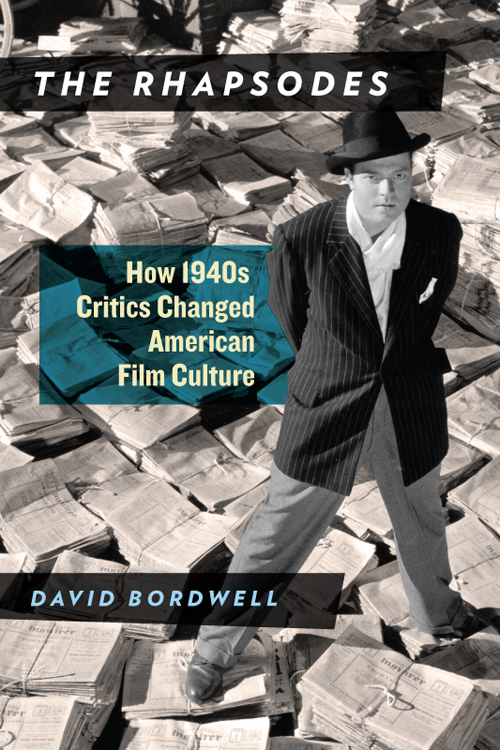

The original entry at this URL, published 23 February 2014, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

I explain the development of the book in this entry.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

Thank you for your interest!

The book stops here: Theory, practice, and in between

Tinpis Run (Pengau Nengo, 1991).

DB here:

Apart from things I’m reading for research (academic monographs, 1940s Hollywood novels, star bios and autobios), the film books I like best are blends. They bring together information, ideas, and opinion. I learn some facts about films and their contexts. I encounter some concepts that illuminate those facts. And I get introduced to some arguments about the best way to understand the information and ideas. In my ideal world, the blend winds up answering some questions—maybe questions I’ve thought about, maybe ones that never occurred to me.

I especially like books that have one foot, or toe, in filmmaking practice. The poetics of cinema I try to practice is, from one angle, an effort to grasp the principles underlying filmmakers’ creative choices. Sometimes those choices are announced by the filmmakers; sometimes we have to reconstruct them on the basis of the films and other data. So for me a drastic split between theory and practice isn’t very informative.

These pronunciamientos are but prelude some comments on books that push several of my buttons. Maybe they’ll do the same for you.

Philosophy goes to the multiplex

Stagecoach (1939); True Grit (1969).

What book brings together Cézanne and Tony Soprano, Gregory Peck and Simone de Beauvoir, Plato and South Park, The Twilight Zone and Wittgenstein?

Okay, I know the answer: Practically every book by a littérateur convinced that Great Big Theory gives you a way of talking authoritatively about anything, especially pop culture. So I rephrase my question: What book brings together these and many more items with care, rigor, and infectious amusement?

That narrows the field quite a bit. A strong candidate is a book that has chapters like “What Mr. Creosote Knows about Laughter,” “Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation,” and “The Fear of Fear Itself: The Philosophy of Halloween”— not the movie but the holiday itself.

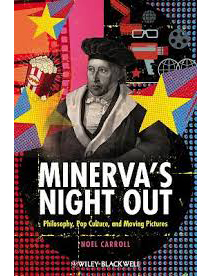

The short answer to my question: Noël Carroll’s new collection of essays, Minerva’s Night Out: Philosophy, Pop Culture, and Moving Pictures.

Noël Carroll isn’t merely the most important philosopher ever to write about popular culture. He has been for decades a major force in film theory and criticism, as well as a philosopher making contributions to moral and legal theory, historiography, and a welter of other areas. His fertile mind and prodigious typing skills have combined to produce over fifteen books and a list of articles running to triple digits.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

This focus on film theory stems from the fact that Noël’s first Ph.D. degree was in film studies. But soon afterward he went on to get a second Ph.D. in the philosophy of art. His cinema research was always philosophically informed, but once he became a card-carrying philosopher, he commuted between two academic areas. He helped found the broader movement called Philosophy of Film, and he continues to write on a lot of different topics. His Humour: A Very Short Introduction is due out in a couple of weeks.

Minerva’s Night Out scans the range of his interests—not only all types of media (which he genuinely enjoys) but a variety of the philosophical puzzles they pose. These he tackles with verve, patient but not plodding analysis, and a range of references that make you wonder if this guy has seen and read pretty much everything.

Here’s the sort of thing that Noël thinks about. We all know that to enjoy a movie fully we often have to appreciate the way in which a star’s performance builds on previous roles. But there’s a problem. The fictional world of a film makes only certain types of knowledge relevant to our experience. At the center of this knowledge is what Carroll calls the “realistic heuristic,” the premise that all other things being equal, the things happening in the fiction are assumed to operate under the laws of our everyday world. Sherlock Holmes (whether incarnated by Basil Rathbone or Benedict Cumberbatch) is presumed to have lungs like the rest of us, unless we’re told otherwise. Likewise, it is true in the fiction that a room’s walls are solid, while they might in reality be fake. If I see the walls as painted sets or green-screen mattes, then I’m not responding to them as part of the story world.

The same attitude shapes our sense of the unfolding plot. Armed with the realistic heuristic, we have to assume that characters’ destinies are open, that many things can happen to them (as with us). But the principles by which a movie fiction is constructed—say, boy gets girl—aren’t part of our realistic heuristic. “What we believe is probable of a movie qua movie is radically different from what we believe to be probable in a movie conceived as a credible fictional world.” Movie lore tells us that boy will get girl, but to grasp and respond to the story emotionally, we have to feel in doubt. (Perhaps this is what people mean when they say that a mistake in the movie, or a distraction in the auditorium, takes them “out of the movie.” We’ve left the fiction.)

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Carroll comes up with an ingenious explanation. Movies summon up star personas in the manner of allusions. Just as our experience is enhanced when we see a movie refer to another movie—Carroll’s example is a citation of Rocky in In Her Shoes—so do our mind and emotions respond to the presence of the star, as either a continuing allusion throughout the film or a one-off one, as with a cameo or walk-on. As he often does, Noël points out that practicing filmmakers use the concepts he elucidates. “Allusive casting” became part of the 1970s trend of paying homage to old Hollywood, but even in the studio era it wasn’t unknown. Carroll points to The Bigamist (above left), in which somebody says another character looks like Edmund Gwenn. Of course said character is played by Edmund Gwenn.

I’ve shrunk down Carroll’s line of reasoning to give you the flavor of the way he thinks. His piecemeal approach to theory focuses not on loosely named topics but specific questions. For example:

What if anything justifies us talking about popular culture as all one thing?

How do fiction films engage us in the emotional lives of their characters? Hint: It’s not through identification.

What makes us laugh at Mr. Creosote, rather than be horrified or disgusted by his vomit-laced gluttony?

How does a tale of dread, such as Poe’s “The Black Cat,” differ from a horror story?

Why should we care about Tony Soprano, who barehanded commits “crimes of which I don’t even know the names”?

Are the feelings awakened by art akin to friendship?

What role do moral emotions, such as the sense of community, play in our response to characters?

As for the jokes, they’re not of the esoteric academic type but rather straight-out funny. Just one essay, on the vague/implausible (you pick) notion that modernity (traffic, window displays, lotsa flashing lights) changed the very faculty of human perception:

The human eye rarely fixates; saccadic eye movement is the norm. We did not suddenly become attention-switching flâneurs in the late nineteenth century; we have been natural-born flâneurs since way back when.

No amount ot cultural conditioning will succeed in making normal viewers worldwide literally see human faces as cross-sections of centipedes.

I’m sure he’d give any indie filmmaker the rights to make Natural Born Flâneurs.

Viewers and their habits

Natsukawa Shizue in Town of Hope (Ai no machi, 1928).

Carroll tries to figure out certain logical conditions on spectators’ experience in general. That’s one province of film theory. But he’s also sensitive to the constraints on those conditions, the ways that historical and institutional circumstances can shape how viewers watch movies. (That’s part of the star-as-allusion argument.) Other researchers, historians by trade but sensitive to theoretical implications, have tried reconstructing the activities of theatres, trade personnel, and audiences in particular times and places.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A similar approach, but focused with razor acuity on a single country and period, is Hideaki Fujiki’s Making Personas: Transnational Film Stardom in Modern Japan. This book is an expedition into a nearly sunken continent, Japanese film of the silent era. Frustratingly few films have been preserved from those years, but paper documents abound. Fujiki has made intense use of them to answer the question: What were the cultural causes and results of the early star system in Japan?

The answers are rich and detailed. The very first stars weren’t on the screen at all; they were the benshi who narrated the silent program. Hideaki goes on to trace the career of the paradigmatic male star, Onoe Matsunosuke, and to show how his main traits (virtuosity and stature as “great man”) were reinforced by a troupe-based business model. Later chapters focus more on female stars, with emphasis on the influence of American actresses like Clara Bow. The flapper figure shaped not only Japanese female performers but women in real life.

Fujiki traces in some detail how the “modern girl” or moga floating through Ginza owed a good deal to Hollywood movies. He makes good use of what films survive from this period, particularly The Cuckoo (Hototogisu, 1922) and Town of Love (Ai no machi, 1928). In-depth analysis of the star image Natsukawa Shizue, above, allows him to discuss fan culture and movies’ role in accelerating trends in fashion and advertising. In all, Making Personas is a fascinating consideration of stardom as both an industrial and social construction in one of the world’s most important national traditions.

Education and environment

Institutions of another sort feature in two impressive books from the prolific Mette Hjort. She has had the very good idea of assembling documentation about how film schools work. How do different schools, academies, and more informal agencies understand the craft of filmmaking? What ethical values and social commitments are brought to the classroom and enacted in the production process? What are the histories of film schools around the world?

The answers come in two packed anthologies, The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, The Middle East, and the Americas, and The Education of the Filmmaker in Europe, Australia, and Asia. From these we learn of the creative practices put into action by institutions in Nigeria, Palestine, Denmark, the West Indies, China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Sweden, Germany, Australia, Japan, and many other localities. We get a real sense of intercultural communication and its breakdowns. Rod Stoneman points out that Tinpis Run, Papua New Guinea’s first indigenous feature, demanded postproduction discussions when outsider viewers couldn’t distinguish the villages presented in the story.

Things happen in these places that would astonish students at UCLA and NYU. Hamid Naficy tells of taking his Qatar students to Tanzania, where they worked on research projects only after spending the morning doing clerical and custodial work in schools and hospitals. We learn of children’s filmmaking initiatives in Mexico City, programs for at-risk youths in Brazil’s City of God favela, and students making photo and sound montages in Calcutta. One purpose of Mette’s collections is to remind us that film training goes far beyond getting your MFA and a showreel on a maxed-out credit card.

Hjort’s initiative, while already stimulating, ought to be continued and enriched. People are starting to understand the importance of film festivals within film culture—as distribution mechanisms, publicity arms, and in a roundabout way feedback systems shaping production. (One essay, by Marijke de Valck, points out the move by festivals toward film training.) More generally, we need to understand film education at all levels as shaping film production and film audiences.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Their first book, Ecology and Popular Film: Cinema on the Edge argues that apart from films like An Inconvenient Truth, which wear their green politics on their sleeve, there’s a much bigger and broader tradition of films about humans and the environment, ranging from fictional films with explicit messages, like Happy Feet (2006), to films with unintentional ones, like The Fast and the Furious (2001).

As “second-wave” practitioners of eco-criticism, Murray and Heumann aren’t much concerned with cheerleading or finding villains. They want to explore how media representations of the environment have responded to various cultural pressures. Their two most recent books are good examples. That’s All Folks? (2009), building on their analysis of Lumber Jerks in their first book, concentrates on American animated features. They perform careful symptomatic readings while also providing industrial context, such as the tactics by which Lucas and Spielberg adapted to the growing dinosaur craze of the 1990s.

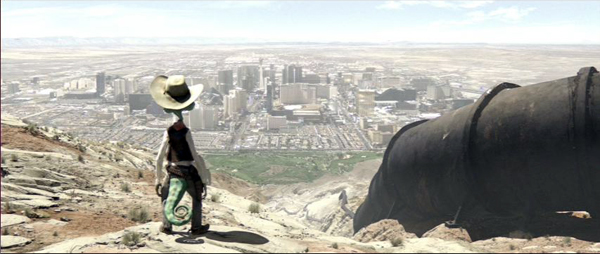

In Gunfight at the Eco-Corral (2012), Murray and Heumann tackle the Westerm on similar grounds, ranging from Shane and Sea of Grass to There Will Be Blood and Rango. Reading these chapters I was reminded how often the genre’s plots hinge on disputes over natural resources. Water, minerals, timber, grazing land, and what the authors call “transcontinental technologies” like the telegraph and the railroad are at the heart of classic Westerns, and the genre’s formulaic conflicts often have strong ecological resonance. This is the sort of criticism that refreshes your vision of movies you think know very well.

Their next book, Film and Everyday Eco-disasters is due out in June.

Things stick together

Lone Survivor (2013).

Finally, two more books merging theory and practice—but from opposite ends of the spectrum. One question that intrigues me involves coherence and cohesion in film. Roughly speaking, coherence involves the way the whole movie hangs together. If it’s a narrative film, how do the scenes or sequences fit into the larger plot? If it’s not narrative, what other principles organize the whole shebang? Cohesion involves how adjacent parts fit together—shot against shot, sequence to sequence. Both these concepts have practical implications, since every filmmaker confronts concrete choices about them in scripting, shooting, and editing.

Michael Wiese has contributed enormously to our understanding of filmmaking practice by publishing a series of books on cinema craft. The most recent one I know is by Jeffrey Michael Bays and it bears directly on cohesion. It’s called Between the Scenes: What Every Film Director, Writer, and Editor Should Know about Scene Transitions. Bays himself has written and directed films, written radio dramas (a great place to study transitions), and published books on filmmaking.

Between the Scenes is an entertaining and damn near exhaustive account of the ways that images and sounds can tie one scene to another. Bays considers aspects of space, like location or objects or actors; time; and visual graphics. The book also shows how sounds can bind scenes or emphasize sharp contrasts. In the example from Lone Survivor above, a soft whir of helicopter blades is heard over the first shot and grows louder when we move from the map to the landing area.

In a web essay called “The Hook” I explored some aspects of this process, but Bays goes into much more detail with many recent examples. He also raises ideas I never considered. For example, if we think of narratives as people traveling from one place to another (and most narratives are that, at least), then every filmmaker faces a choice: Show the journey or don’t show it. And if you show it, what parts and why and what does it tell us about the character? The larger point is: “Make sure you know where every character goes between every scene.” Thinking about this suggests ways to enrich your presentation, and it allows the characters—if only in your imagination—to inhabit a more fleshed-out world. Ideas like this can provoke everyone, filmmakers and film scholars alike.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

This example is simple, but once Chiao-I gets going, she’s able to show how nearly every cut or camera movement can be seen as activating a unique tissue of cohesion devices. The words in a paragraph not only refer to ideas or things; they also link to other words in the paragraph and in the larger discourse. Similarly, in film, different aspects of the images and sounds stand out and adhere to one another instant by instant. Tseng’s analyses of passages in Memento, The Birds, The Third Man, and other films are accompanied by equally close studies of television commercials and educational documentaries. At the end, analysis is supplanted by synthesis, as she shows how the configurations she has pulled apart coalesce into levels that highlight characters and actions. It’s a fresh way to think about how we understand films within genres and stylistic traditions.

In effect, she’s showing the fine-grained patterns that emerge from the choices every filmmaker faces. It would be fascinating to sit in on a dialogue between Bays and Tseng, for they belong to the same community, or so I think anyhow. We’re all trying to understand aspects of cinema, and by focusing on certain phenomena rather closely, we have a good chance to understand them better.

So to the filmmaker who’s skeptical of theory, I say: We can’t think clearly without concepts, or talk clearly without terms. We need to develop rigorous ideas and arguments (i.e., theory) to understand film as best we can. But to the would-be theorist I say: Keep fastened on the look and feel of the films, and test your ideas and arguments not only against them, but against what you can find out about the craft of cinema, in all its historical implications.

I was pleasantly surprised, after I’d decided to talk about these books, to find work by Kristin and myself cited in some of them. Remaining coldly objective, however, I didn’t let these mentions diminish my praise.

Rango (Gore Verbinski, 2011).

Nothing, if not critical

The Woman in the Window (1944).

O, gentle lady, do not put me to’t,/ For I am nothing, if not critical.

Iago, Othello

DB here:

Movie aficionados seem endlessly interested in film criticism—not just in what a writer says about a film, but in the very idea of criticism. I’ve suggested in a recent entry some of the historical reasons for this: the rise of the celebrity reviewer in the 1960s, the surge in interest in foreign and alternative cinemas, the emergence of filmic experiments, from Persona to Memento, that seemed to demand discussion.

With the internet, you can’t turn around without bumping into a film review. Aggregate sites like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic get tens of millions of hits a month. Of course many people are just checking on the range of opinions of a specific release, but I get a sense that many readers are more or less addicted to critical buzz as such. Connoisseurs of sentiment and snark, they still follow favorite reviewers just as we did in the 1960s, and they enjoy reading a critic they don’t agree with because she or he is an enticing writer.

In one corner of my workroom a steadily growing pile of books is no less a tribute to the flourishing of film criticism. Yes, books. I’m a committed Netizen (I’d better be, after three e-books, several web essays and videos, and over 610 blog entries). And for certain purposes, such as word search, I prefer digital versions of texts. But nothing beats a book for reading anywhere you happen to be, thumbing back to check a point, marking up margins with invective, and throwing across a room when you’ve decided the author is a dunce.

Here, though, are some books that won’t become missiles.

Revaluation

One consequence of the 1960s cult of the movie critic was a new genre of book—the anthology of a writer’s reviews, think pieces, and long-form essays, perhaps spiced by an interview or two. Call it a predecessor of a website if you must, but such books were tempting packages to cinephiles who wanted their fix in big gulps, not weekly doses. Then we eagerly read through Agee on Film, Dwight Macdonald on Movies, Kael’s I Lost It at the Movies, and many other collections. Some of these are now classics, most are forgotten, but the format still has life in it. Roger Ebert, exceptional in all respects, kept it going for years and crowned it with his Great Movies series. The format passed to academic presses like Wesleyan with Kent Jones’ Physical Evidence (2007) and Chicago with Dave Kehr’s When Movies Mattered (2011).

Like me, James Naremore is a creature of the 1960s, but with his typical discretion he has waited forty years to bring together a collection. Jim’s 1973 Filmguide to Psycho introduced me to his elegant thinking about movies. Since then he has written about a great many subjects, always with wit, steady vision, and deep and unostentatious learning. Now we have An Invention without a Future: Essays on Cinema (University of California Press).

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

The latter pieces were among Jim’s efforts at real-time film reviewing at Film Quarterly. Perhaps the sharpest edge of the book comes in the section housing them, called “In Defense of Criticism.” Jim, I think, considers criticism as, say, Lionel Trilling or Edmund Wilson considered it. Endowed with a tolerant, generous mind, the critic uses all the resources of culture—philosophical and moral ideas, social forces, artistic traditions—to illuminate the unique identity of the artwork.

More deeply, the critic expects the encounter with the artwork to challenge and change us. This to me is one difference between the reviewer and the critic. The reviewer expects the film to live up to his or her solidly entrenched point of view. The critic is open to being shaken, taught, and even transformed by the film. The reviewer projects confidence, the critic displays curiosity.

This ambitious conception of criticism is at risk today from two forces. There is the sheer blather of pop journalism and the Internet, which have pushed film culture from criticism to comments to chat to chatter. At the other end, some professors are allied against film as an art.

Today the humanities are in danger of losing their soul. Academic film studies has tended to focus on formal systems, industrial history, fandom, and identity politics—essential topics without which good criticism can’t be written, but topics that don’t engage directly with questions of art and artists.

Admitting that a certain detachment is valuable for research purposes, Naremore thinks that academics have become somewhat too clinical. Part of his book’s purpose is to draw their attention back to the intellectuals who flourished outside the academy, and for whom quality was worth arguing about.

I nevertheless think that evaluative criticism needs to be encouraged more, and I miss the days before the full-scale development of film studies, when film was made exciting and relevant by virtue of critical writing and debates over value.

So the last section consists of thoughtful essays on James Agee, Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, and Jonathan Rosenbaum—those who “had the greatest influence on the development of my taste.”

For my $.02, I’d just add that appraisals of quality shape a lot of academic writing, even in the Cult Studs vein. Showing that a film is racist or classist is surely an exercise in evaluation, employing moral or political criteria. Showing that fans of Twilight aren’t dumb no-hopers often springs from the researcher’s own esteem for the franchise. (Remember one of The Blog’s mottos: We are all nerds now.)

In effect, I think, Jim is pointing out that in a lot of film studies evaluation isn’t framed in specifically artistic terms. On that I’d certainly agree. Jim opens a new conversation by asking academics to look beyond their specializations and learn how the best arts journalists argue about quality. Seriously thought-through yet accessible to all, An Invention without a Future is a bracing, quietly subversive book.

Auteurs: From the ridiculous to the sublime

Jim would find signs of hope in two books dedicated to major directors.

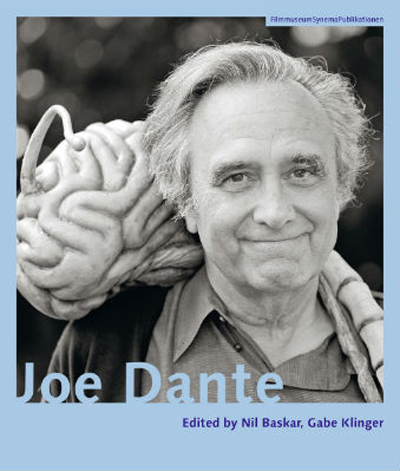

Nil Baskar and Gabe Klinger’s Joe Dante, a collection from the enterprising SYNEMA series at the Austrian Film Museum. Dante is just the sort of auteur that cinephiles prize. Working on the fringes of the system in despised genres, he’s a Movie Brat who loves B cinema, noir, and crazy comedy. This thick, square book contains virtually everything you’d ever want to know about the man who could be seen as Spielberg’s demented, funnier alter ego. Dante’s kiddie adventure stories and teen terror pix have celebrated and parodied Americans’ feverish love of war, big business, junk food, and lunatic media.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

Dante’s opposite number is Béla Tarr, whose films run the gamut from glum to morose, but they’re no less exhilarating. They find their ideal explication in András Bálint Kovács’ The Cinema of Béla Tarr: The Circle Closes. Kovács scrutinizes all the films, some little-known outside Hungary, and produces careful analyses that balance thematic interpretation with precise examinations of style. As a friend of Tarr’s, András is in a unique position to take us into this filmmaker’s grimy, splendid world.

Tarr, Kovács suggests, asks his audience to accept the illusions shaping the narrative world. Yet his structure and technique in the end yield a clearer view of the underlying forces than the characters can achieve—often, forces driven by conspiracy or betrayal. Accordingly, Tarr’s narratives tend to be cyclical, even when the story situation is unchanging, and his camera movements often trace a circular path. Many readers will particularly welcome Andras’ exciting account of Sátántangó, Tarr’s most demanding film. Based on a novel with an intricately circular structure, the film finds its own means to suggest a story swallowing its own tail. Most film books nowadays have pretty good frame illustrations, but these are well-sized to illustrate some of Tarr’s fine points of staging. In all, this book is likely the definitive study of Tarr’s art.

Museum pieces

There’s another way to make the case for an auteur’s value: produce a dazzling book that pays tribute with gorgeous illustrations and informed critical commentary. This has been done by Taipei’s Museum of Contemporary Art in its catalogue King Hu: The Renaissance Man.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

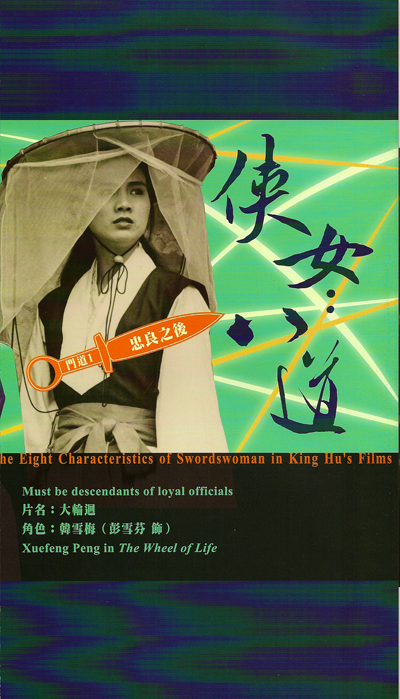

Open the catalogue and you’re greeted by a large gatefold that sums up King Hu’s career. Thereafter, articles like Edmond Wong’s study of King Hu’s archetypes (derived from legend and theatre) supply the academic ballast, while images of the gallery displays fill up page after page. There are photo essays devoted to each of the films, as well as more gatefolds, illustrating themes such as “The Eight Characteristics of Inns in King Hu’s Films.” Just the hundred pages of King Hu documents—stills, portraits and self-portraits, along with caricatures of Bill Clinton and Princess Di—would be worth our attention. In all, this is the sort of museum show every cinephile dreams of visiting.

Art historian Steven Jacobs, author of The Wrong House, has collaborated with Lisa Colpaert to produce a dream of another sort. Their book invites you into an imaginary exhibition.

Visualize a museum containing all the paintings you find in films of the 1940s and 1950s. Now assume that some diligent scholar has sniffed out the provenance of all of them and provided stylistic and thematic commentary. And now assume that the research is presented as a guide to this virtual museum, using all the paraphernalia of art-historical commentary.

Confused? Here’s the opening of one entry:

[III.9] Portrait of Lady Caroline de Winter

(Unknown Artist, late 18th Century)