Archive for 2014

DVDs and Blu-rays for your letter to Santa

The Cure (1917)

Kristin here:

One occasional feature of our blog has been to point out new releases on DVD and Blu-ray, especially of titles that haven’t gotten much publicity. Some of these are easily available at major sources like Amazon, while others have to be ordered directly from their publishers, often abroad. But if you have a multi-standard player, don’t hold back. Ordering from abroad isn’t as intimidating as it might seem. Many sites have English-language sales pages.

We’ve done a lot of these entries by now. You can find them through the DVD category in the list at the right, but I thought it might be useful to give links to all of them here, with brief indications of what each deals with. Some of the DVDs are probably out of print by now, but in this era of eBay and third-party sellers, one can usually track down such things. Then I’ll give a rundown on some recent releases.

The first was Dispatch from the Land of the Long White Cloud, written when David and I were fellows at the University of Auckland in May, 2007. I discussed some of the DVDs of New Zealand films that I had found in stores there. Some are famous, some obscure.

2008 was either a great year for DVDs or we just had more time to deal with them. On January 18, I posted Tracking down Aardman creatures, a guide to the classic animated films of Nick Park, Peter Lord, and their colleagues at Aardman. At the time it was probably the most complete information one could get on these films. Of course, Aardman has gone on to make other films and TV series, but this was the studio’s golden age. On February 1, I described with two boxed sets dealing with early sound films in All singing! All dancing! All teaching! As the title implies, these are a boon to film teachers, as well as buffs and researchers. In Coming attractions, plus a retrospect (June 6), David discussed the release of Robert Reinert’s very peculiar silent film, Nerven, and in Summer show and tell (July 28, 2008), he briefly dealt with a miscellaneous set of DVDs and books that we discovered during our annual visit to Il Cinema Ritrovato and other destinations. On December 10, in Preserving two masters, I discussed the restored version of Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao (which at that point wasn’t out on DVD) and a Walter Ruttmann set.

2009 was a pretty good year, too. On February 18, I wrote about the Flicker Alley release of Abel Gance’s influential classic La roue, including historical background on the film, in An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film. David took the occasion of of a new Criterion boxed set to summarize the work of the fine Japanese director Shimizu Hiroshi (May 9). On May 21, in Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD, I described two major boxed sets, one of Lotte Reiniger’s lovely but seldom-seen fairy-tale shorts, and one of early Belgian avant-garde cinema–and yes, the early Belgian avant-garde cinema includes some important titles. On August 2, David again caught up with the mixed batch of DVDs and books picked up in Europe over the summer or sitting in the stack of mail upon his return, in Picks from the pile. Finally, on November 9 I discussed the British release of Dreyer’s Vampyr with a very worth-while commentary track by Guillermo del Toro, who said, among other things, “I am not Carl Dreyer, and I should shut up.”

In February of 2010, I wrote DVDs for these long winter evenings, dealing with three sets with the work of three crucial filmmakers: Georges Méliès, Ernst Lubitsch (most of the German features), and Dziga Vertov. In October, it was More revelations of film history on DVD: a documentary on Veit Harlan, a new series of Soviet silent films, and the Flicker Alley set of Chaplin’s Keystone films. (For the follow-up, see below.) On November 28, Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings covered little-known Norwegian and Danish silents, a rare Expressionist film, Ford’s The Iron Horse, hilarious Max Davidson comedies, and the Kalem company.

For some reason it was a full year before we posted more DVD coverage in our second Christmas-gift-themed entry, Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, in time for a fröliche Weihnachten! (November 29, 2012). It probably took us that long to get through all the discs we picked up in Bologna and elsewhere. The title reflects the heavily German coverage: early Asta Nielsen films, Pabst’s first feature, the release of Das Weib des Pharao on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as the 1939 Hollywood version of The Mikado.

Earlier this year, on June 20, we posted our most recent DVD/Blu-ray entry, Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book. It deals with a burst of releases of Norwegian silent films, a new entry in the “American Treasures” archive series, and some American films, famous and obscure.

Now more DVDs are piling up, and the time seems ripe for a third set of holiday-present suggestions, to give or hope to receive.

Caligari, restored at last

In our survey of the ten best films of 1920, I mentioned that Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari was one of the films that lured me into film studies during my undergraduate days. I know it very well. I was tempted to go to one of the screenings of the recent restoration this year at Il Cinema Ritrovato, but it was opposite other films I had never seen before, so I passed it up. Luckily now Kino Lorber has brought that restoration out on DVD and Blu-ray (sold separately).

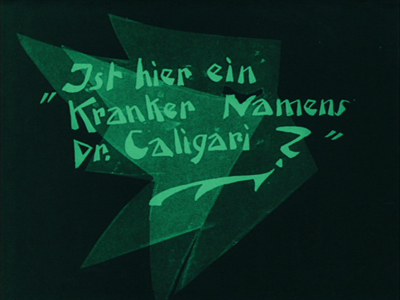

The negative of Caligari does not survive in its entirety, but the restoration has taken the usual steps to fill it in and provide authentic tinting. The information comes from titles at the beginning of the DVD print:

The 4K restoration was created by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in Wiesbaden from the original camera negative held at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin. The first reel of the camera negative is missing and was completed from different prints. Jump cuts and missing frames in 67 shots were completed by different prints.

A German distribution print is not existing. Basis for the colours were two nitrate prints from Latin America, which represent the earliest surviving prints. They are today at the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf and the Cineteca di Bologna.

The intertitles were resumed from the flashtitles in the camera negative and a 16mm print from 1935 from the Deutsche Kinematek-Museum für Film und Fernsehen in Berlin.

The digital image restoration was carried out by L’Immagine Ritrovata-Film Convservation and Restoration in Bologna.

The images are definitely clearer, with more detail visible than in prints I have seen before, and the film runs more smoothly. An inauthentic intertitle has been removed. In most prints, when the grumpy town clerk hears that Caligari wants a permit to exhibit a somnabulist, he calls him a “Fakir” and turns him over to his underlings to deal with. That title is now gone, and it’s clear that Caligari is annoyed at the man’s disdainful attitude rather than a specific insult. The intertitles have their original jagged, Expressionistic graphic design (see above) rather than the plain backgrounds used in many prints hitherto available.

There are optional English subtitles. The modernist musical track fits well with the film.

The supplements include a short essay which I provided and a documentary, Caligari: How Horror Came to the Cinema. The restoration is also available from Eureka! in the United Kingdom, with a different set of supplements and with DVD and Blu-ray sold together.

Flooded by flickers

If you want a lot of good laughs and have 1005 minutes to spare, Flicker Alley’s “The Mack Sennett Collection Volume One” offers 50 restored shorts which Sennett acted in, wrote, directed, and/or produced. (This 3-disc set is available only on Blu-ray.)

The films are presented in chronological order, starting with a 1909 comic short directed by D. W. Griffith at American Biograph and starring Sennett, The Curtain Pole. Two comedies directed by Sennett at American Biograph follow. In 1912 he founded Keystone, represented starting with The Water Nymph (1912) and ending with A Lover’s Lost Control (1915). In 1915 Sennett became one of the three points in the Triangle Film Corporation, along with co-founders Griffith and Thomas Ince. Keystone continued operating as Triangle Keystone, and films from that production unit from 1915 to 1917 are included. At that point Sennett went independent as Mack Sennett Comedies, making mainly two-reelers, beginning in this collection with Hearts and Flowers (1919) and running to The Fatal Glass of Beer (1933). See here for a complete list of titles. Each of the three discs contains a group of films as well as a set of bonuses at the end.

Sennett built a team of excellent comedians, including at various points Ben Turpin, Chester Conklin, Charlie Chaplin, Ford Sterling, Wallace Beery, Louise Fazenda, Mabel Normand, and others. The action typically moves at a breakneck pace, and the editing is similarly fast. Being able to go back and watch some of these routines again, perhaps in slow motion, is ideal for making sure you catch every throw-away gag.

A Clever Dummy shows off the dexterity of the cross-eyed Turpin. Two inventors build a mechanical dummy, modeling “him” on the janitor played by Turpin. At first the dummy is a rather cheap-looking fake, but Turpin plays him in some scenes and the janitor in others. Then he decides to masquerade as the dummy, and his antics persuade some vaudeville agents to buy him for their show (left below). Once in the theater, he defies a stagehand’s (Conklin) efforts to make him stand quietly (right):

Savor these a few at a time, and you’ll have entertainment for months to come.

Of course, some of that 1005-minute total comes in the bonuses. There are newsreel and television appearances by Sennett, including “This Is Your Life, Mack Sennett” (1954) and a half-hour radio appearance on the Texaco Star Theater in 1939.

Back in 2007, we posted an entry called Happy Birthday, Classical Cinema!, where we explained how the guidelines and techniques that came to underpin what we now call classical Hollywood cinema came together in 1917. At the end we offered a list of the ten best films of that year, and thus inadvertently our annual ninety-year celebration, “The ten best films of …” came into being. On it were two Charlie Chaplin films, The Immigrant and Easy Street.

They were both made during the third phase of Chaplin’s career, when he had left Keystone and gone first to Essanay and then to Mutual. Those who find the pathos in many of Chaplin’s films from the 1920s onward might plausibly consider his Mutual period to be the height of his career. The twelve films are not all equally brilliant, however. One watches Chaplin developing a better sense of story-telling to go with the slapstick. The Rink comes across as two one-reelers stitched together. In the first half having Charlie does a fairly conventional waiter schtick, but when he visits a rink on his lunch-hour, the films moves into high gear as he performs a dazzling set of moves on skates:

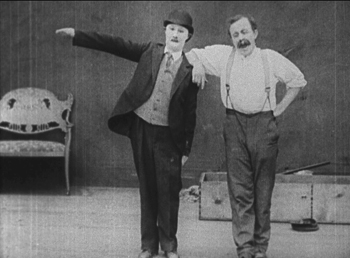

Other films show Chaplin learning to make a sustained, tight story built of non-stop gags, none more skillfully than The Cure. An alcoholic forced into a sanatorium evades all attempts to make him shape up while charmingly defending the heroine from an offensive, gout-ridden villain (see top, where all involved briefly strike a pose).

Flicker Alley has released a steelbox commemorative set of five discs, two Blu-ray and three DVD, to celebrate the centenary of Chaplin’s first appearance as the Little Tramp–though of course that appearance had been made at Keystone.

For a list of film titles and bonus features, see here.

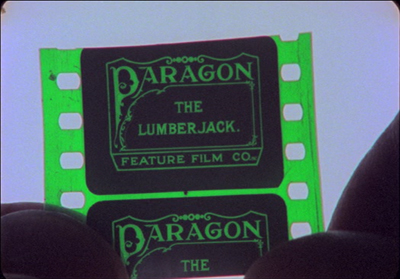

If these sets contain some of the most famous films and performers of their day, another recent Flicker Alley release, We’re in the Movies: Palace of Silents & Itinerant Filmmaking, turns to some of forgotten and obscure offerings of the silent era: films made in small towns by independent regional producers, using local citizens for their casts. Earlier this year, David wrote about Wheat and Tares, a 1915 film made in his home town by the Penn Yan Film Corporation. That’s not one of the locally made films included in We’re in the Movies, but this two-disc set (both DVD and Blu-ray) does contain The Lumberjack, a short film made in Wausau, Wisconsin and discovered in the early 1980s by Stephen Schaller, then a graduate student in film studies here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Schaller didn’t just discover the film. He created a lovely, poignant documentary, When You wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose (1983), about the making of the film and the history of the one print and how it survived. He tracked down and interviewed several elderly people who had been involved with its making. These included Florence Gilbert Evans, the only surviving cast member, and relatives and friends of others “actors.” At intervals throughout the film, he interviews Louise Elster, who had accompanied silent films on piano in local theaters. She provides a lively commentary on such accompaniments and plays examples as skillfully as she must have done in the day. (Modern-day silent-film accompanists might find many tips from this documentary.)

The only problem with the film is that no identifying titles are superimposed to tell us who these people are, and often their names are not mentioned in the interview excerpts included. One has to struggle at times to figure out who the speakers are and what they had to do with The Lumberjack. Names are only given in the final credits, and even then their connections to the film are not specified. Still, the story of the film’s making comes together clearly enough.

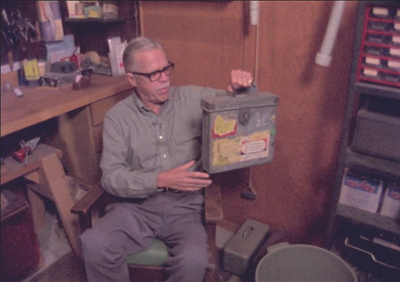

Schaller reenacts the finding of the film itself in a scene with Robert S. Hagge. Hagge, who apparently worked at the Grand Theater, where the sole print resided until 1946, when he took it to his home:

The poignancy of The Lumberjack‘s history emerges gradually as we get to know those involved and their histories. One of the producers was accidentally killed during a quarry explosion staged for the film. Settings shown in the movie are compared with the current appearances of the same places, with some beautiful old buildings preserved and others replaced by bland modern structures. There is a hint that the making of the film created an excitement that transformed the lives of the Wausau citizens involved. When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose illustrates the power of even the most modest of films and the inevitable losses caused by the passage of time.

The set also includes a 2010 documentary, Palace of Silents: The Silent Movie Theater in Los Angeles, devoted to a theater built in 1942 and dedicated for over 68 years to showing silent films. The rest of the contents are The Lumberjack and other early local films.

These films strike me as an excellent way of intriguing students and film fans about the silent era of the movies.

Oktoberfest as seen through the movies

I was somewhat surprised to see the new two-DVD set in the Filmmuseum München series: Oktoberfest München 1910-1980. It’s an interesting approach, gathering together the surviving films about a single annual event, Munich’s famous Oktoberfest. As the accompanying booklet points out, the Oktoberfest was a venue where early traveling exhibitors set up their tents to show movies, though little documentation of these shows survives. No one knows when the first films about or set at the festival were made. The earliest one to survive is from 1910.

Oktoberfest was and is more than beer-drinking. There are parades, rides, and various fairground activities as well.

To many film historians, one of the attractions of this collection will be a film starring the comedian Karl Valentin, Valentin auf der Festwiese. The nominal plot involves Valentin taking his wife to the festival while planning to meet his mistress there and sneak away. This story gets shunted aside for most of the film’s length, however, as the couple wander through various sideshow tents. We see their grotesque reflections in a fun-house mirror (above), and the camera perches in a ferris-wheel seat to record the long-delayed confrontation of wife and mistress.

One curiosity of the set is a 3D film from 1954, Plastischer Wies’n-Bummel. The analglyph 3D glasses (red and cyan) required for the effect are included in the set. I found it something of an effort to resolve the 3D in many shots, but there are some dramatic depth effects involving balloons and some fairground swings that work quite well:

The booklet is in German, English, and French, and there are optional subtitles in English and French. The DVD set can be ordered online here.

Making a list, Czeching it twice

When we were in Prague this summer, Michal Bregant, head of the National Film Archive, gave us some books and DVDs related to early Czech animation.

One was a catalog published by the archive, Czech Animated Film I 1920-1945 (2012, bilingual in Czech and English), with a short historical introduction and descriptions of all the known films of the period. It relates to a two-DVD set, Český animovaný film 1925-1945 (Czech animated film). This delightful collection contains 30 shorts and has optional English subtitles. Some of the cartoons are outright imitations of American series of the day, such as Hannibal in the Virgin Forest (1932), clearly inspired by early sound cartoons from Disney and Warner Bros.:

There are also two early György Pál (later aka George Pal) cartoons. Many of the shorts, though, are advertisements. As in other countries where major filmmakerss like Len Lye were doing inventive work for ads, Czech animators came up with some amazing images. Margarine never looked as good as in Irena and Karel Dodal’s 1937 Gasparcolour short for the Sana brand, The Unforgettable Poster (see bottom).

The Dodals were the most important Czech animators of this era, as is shown in a well-illustrated biography, The Dodals: Pioneers of Czech Animated Film, by Eva Strusková (published by the National Film Archive in 2013). It’s in English and comes with a DVD. (There is some overlap between its contents and those of the two-disc set.)

Both are musts for animation experts and fans. The Dodals is available from Amazon. The DVD set won as “Best Re-discovery 2012/13” at the Il Cinema Ritrovato awards last year. It and the catalog can be ordered directly from the National Film Archive website or from a specialized cinema shop in Prague, Terry Posters (this link takes you to the English-language version of the site).

The Unforgettable Poster (1937)

What-if movies: Forking paths in the drawing room

Dangerous Corner (1934).

DB here:

We habitually indulge in what-if thinking. What if you hadn’t gone to that particular school, met those specific friends, lived in that particular place? Your future would have been very different, in ways you sometimes speculate about. Here is Brian Eno explaining how he found his career:

As a result of going into a subway station and meeting Andy [Mackay], I joined Roxy Music, and as a result of that I have a career in music I wouldn’t have had otherwise. If I’d walked ten yards further on the platform or missed that train or been in the next carriage, I probably would have been an art teacher now.

We think this way on a small time-scale too. If you had left that damned parking lot a little earlier, you wouldn’t have had the fender-bender you had down the street.

Just as flashbacks exploit our common-sense intuitions about memory, other narrative strategies tap our habit of what-if thinking. Some movies evoke alternative but parallel fictional worlds. The most recent what-if movie I know is Edge of Tomorrow, whose tagline and video release title, Live Die Repeat, sums up its premise. I thought it was an ingenious use of the format, although the ending left me puzzled. Earlier on this site I wrote about a more intriguing example, Duncan Jones’s Source Code. Sometimes I call these “multiple-draft” plots because they keep revising the action until it comes out right.

Hong Sangsoo has explored the what-if possibility with unusual energy, but he’s less explicit about setting up the structure than Hollywood films are. With his movies, sometimes you don’t realize you’re in a parallel-world plot until you notice repetitions of action with tiny differences. (We have entries on Hong here and here and here.)

Some years back I wrote an essay, “Film Futures,” in which I analyzed the what-if, or “forking-path” narrative. That essay, revised for the book Poetics of Cinema, is now available on this site. It explores several examples: Kieślowski’s Blind Chance, Tykwer’s Run Lola Run, Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be Number One, and Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors.

One Hollywood experiment in this vein was a film version of J. B. Priestley’s 1932 play, Dangerous Corner. I mentioned the play in the essay, but I wasn’t then aware that a film version had been made by RKO in 1934. (To add an extra sting to my ego, it was sitting in our massive collection of RKO movies on campus.) I learned of it just recently when it aired on Turner Classic Movies, a national treasure I have celebrated before. The film quickly showed up online at Rarefilmm, and probably elsewhere.

In the essay, my approach was to treat these films as a sort of genre. What conventions rule them? What motivates the forking-path format—a science-fiction device such as a time machine, or fortunetelling, or something else? How do they tap our what-if thinking? Dangerous Corner lets me test my proposal on a new instance and offer a trailer for a new online essay.

As with any comprehensive narrative analysis, there are spoilers.

They have been here before

Darkness. We hear a gunshot and a woman’s scream. The stage lights come up and reveal some women in a drawing room listening to a radio play, “The Sleeping Dog.” Soon they’re joined by their male partners. An inadvertent remark by one of the women starts a cascade of confessions. The couples reveal a seething mass of illicit affairs, drug addiction, and repressed sexual desires.

As a result of the frenzy of truth-telling, the husband who set the process in motion lurches offstage and shoots himself. Darkness descends; a woman’s scream. When the lights come up, we are back in the drawing room. The broadcast play is at the same point as before. This time things go differently, and music from the radio fills the room as the couples enjoy a banal evening.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

In the course of evening number one, all sorts of naughtiness are revealed. Martin, much loved by all, is revealed to have been a thrill-seeking drug addict with whom Robert’s wife Freda has been having an affair. Olwen is secretly in love with Robert. Gordon’s wife Betty is Charles’s mistress. Gordon in turn is in love with Martin, and we’re to understand they’ve had an intermittent gay affair. Martin has died not by suicide but by accident, when Olwen was struggling to escape from his attempt to rape her. In all, the three publishers’ private lives would suffice for a steamy best-seller.

The point of Priestley’s play is that revealing the truth is a risky business, like driving around a dangerous corner. He uses the forking-path format to suggest the harm of revealing things best kept hidden. Hence the radio play’s title, a reference to letting sleeping dogs lie. For Priestley, however, the parallel-worlds conceit was more than an artistic device. He insisted that Dangerous Corner not be regarded as a dream play but rather “a What Might Have Been.” It proceeded from Priestley’s deep interest in time, which he saw as not merely the linear, “once-and-for-all” track of daily life.

Our real selves are the whole stretches of our lives, and . . . at any given moment during those lives we are merely taking a three-dimensional cross-section of a four-, or multi-dimensional reality.

The same interest in time as split or looped is seen in his 1937 plays Time and the Conways and I Have Been Here Before.

The film version of Dangerous Corner makes some important changes. As you’d expect for a film of the 1930s, the gay plotline and the drug addiction are excised. The character of Charles (Melvyn Douglas) is made more virtuous. He is revealed as the thief, as in the original, but here he has stolen the bonds to help Betty pay off gambling debts. She is no longer his mistress but a friend he is protecting. In addition, Charles is shown pursuing Ann (the play’s Olwen), who turns aside his proposals of marriage. At the end of the film, she agrees to marry him, providing a romantic wrapup.

The first seventeen minutes of the film establish the Charles-Ann courtship and present portions of the play’s backstory. We witness the three men discovering the theft of the bonds, and soon we watch Charles’ discovery of the dead Martin. An inquest declares the death a suicide, and a year passes. Now begins the play’s opening situation, with the women in the parlor. But there’s no longer a radio play running; instead, they’re listening to music before they hear a gunshot. That turns out to be the result of Robert’s firing his pistol into the garden to show it off to Gordon and Charles.

Coming into the drawing room, the men pair up with the woman and banter with their guest, the novelist Maude Mockridge. (She’s in the play as well.) The radio becomes important when Gordon goes to it to tune in some dance music, but the tube fails and, as he puts it, “I guess we’ll have to talk.” From then on the film follows the general contours of the play, and I think it exemplifies the conventions of forking-path plots pretty well. What are those conventions?

Using the correct fork

In the essay I start by suggesting that the action in forking-path plots is understood to be linear. Within each track, there is a smooth progression of cause and effect. Both play and film obey this condition through the simple chronology of scenes, but it’s also controlling the puzzle of the missing bonds, which is eventually explained by detective-story logic. Charles admits to taking them, and in the film Betty further explains that he did it to cover the gambling debts she wouldn’t confess to Gordon.

Linearity is also reinforced by a simple either-or switch. In the film’s tell-all version, Gordon can’t play dance music on the radio because there isn’t a spare tube for the radio set. Then begin the exposures of all the peccadilloes. In the alternate-reality version, there is a spare tube in the drawer, and so the exposures can be averted. Tube there: certain things follow. Tube not there: other things follow. Each chain of events proceeds without break or further splitting.

The radio tube is part of the film’s use of a second principle, what my essay calls signposting. If we’re to understand that there are alternative plotlines, we need some clear markings. In the film, we get several.

First there is the “reset” moment in the second version, when we return to the women moving to the French windows and hearing Robert’s firing of the pistol into the garden. That is a pure replay. What follows reiterates the action we saw earlier: The men joining the women, the radio announcing the time, and the initial chat before the signal fails and Gordon looks for—and this time, finds—a fresh radio tube. He thoughtfully reiterates the split for us. Dancing with Betty, Gordon says: “If Freda hadn’t had that spare radio tube, there wouldn’t have been any dance music, and then—well, anything might have happened.” As I suggest in the essay, characters in forking-path plots often get quite explicit about the what-if premise.

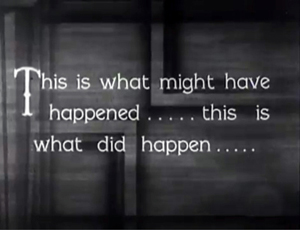

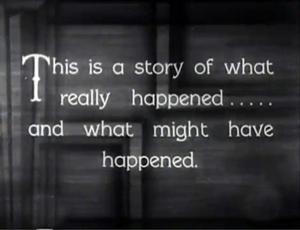

More unusual is the film’s use of intertitles as signposts. Robert, overcome with despair by the results of his relentless demand that everyone confess, runs to his room and shoots himself. The screen goes dark, with traces of smoke. Then we get this title:

At face value, this intertitle says that the stretch of time in which the characters exposed their private lives (the first “This”) is fictitious, while the amicable, truth-concealing version we’re about to see (the second “This”) is veridical.

Is this a bit of hand-holding for an audience that wasn’t prepared for the forking-path device? It does have that function, and to our taste it’s probably too explicit signposting. But it’s more interesting than it appears, because it reverses an intertitle that appears in the film’s opening.

Before the action starts, we get this expository title.

Even without knowing how the film will develop, we are invited to imagine a two-part structure. After seeing the whole film, we can see that this puts the dual worlds on the same footing. The phrasing could be suggesting that the cascade of admissions we’ll see is what really happened, while the smooth social veneering of the final scenes was only an alternative possibility. At the climax, we’ll see the second title as a revision of this slightly puzzling one, which now might seem a bit of playful misleading.

But I think this first title is ambiguous in an intriguing way. The film really has three parts. First there are the 1933 events outside the drawing room, involving the robbery and Martin’s apparent suicide; these scenes aren’t in the play. Next block is the first, confessional versions of the 1934 evening. The third part is the alternative, calm version of the 1934 evening. From this angle, the first title is telling us that the 1933 section leading up to the crucial evening is “what really happened,” and that is indeed the case. We don’t get alternative versions of the robbery or Martin’s death. Accordingly, the sordid first iteration of the evening, the film’s second part, becomes “what might have happened.” In a weird way, the title is accurate about the first two chunks of the plot.

In other words, I’m suggesting that the titles fit the film’s structure as follows. The first title is in red, the second in green.

“This is a story of what really happened…”: The 1933 section.

“…and what might have happened.”/“This is what might have happened…”: First, scandalous version of 1934 evening events.

“…this is what did happen.”: Second, banal version of 1934 evening events.

Anyhow, two versions of the evening are quite enough for us. We can imagine more, but in films we never really encounter the radical plurality of multiple worlds. The physics of a true multiverse would offer indefinitely many variants, including ones in which any particular person doesn’t exist. In some worlds, Gordon would be married to Ann, Robert would court Betty, Charles would be a terrier, and so on. But—and here’s my third principle of such storytelling—the usual forking-path plot revisits essentially the same story world with the same characters, relationships, and settings, and most of the same actions. I call it the principle of intersection.

Intersection assures that we don’t get overwhelmed by having to meet a raft of new characters, figure out new settings or time periods, and generally reorient ourselves with each path we’re led down. Forking-path plots, from A Christmas Carol to It’s a Wonderful Life, keep things simple for us by changing very a few features of their rival worlds. Despite Priestley’s belief that each instant of our lives opens up many alternatives, that gigantic exfoliation of actions is very hard to dramatize and even harder for us to keep track of. So in both play and film, we have the same small world, with only a few differences. That works to the plot’s advantage, because those small differences—the radio works/ it doesn’t work, the cigarette box attracts attention/ it doesn’t—can be given enormous importance.

More rules

A fourth principle of forking-path plots involves the use of cohesion devices—elements of story or narration that smoothly link scenes. Cohesion devices are mid-sized examples of Hollywood’s love of continuity on every scale: cause and effect across the whole plot, foreshadowing of a later scene by an earlier one, hooks between sequences, and at the finest grain, shot-to-shot matching. Accordingly, each path in a forking plot ought to lead us along as easily as a normal plot would.

The essay mentions appointments and deadlines as common cohesion tactics. These aren’t very prominent in either the play or the film version of Dangerous Corner, chiefly because the forked action takes place in such a limited time span. But other devices, such as dissolves and fades, help the parts stick together. In the film a flashback dramatizes what Ann says took place on the night of Martin’s death in a way that fits tidily into the overall arc of the plot.

More interesting in the film are the parallels, a common byproduct of forking-path construction. At a macro-level, the two or three or however many paths are sensed as equivalent, variant versions that the viewer is invited to liken or contrast. And both our play and film reiterate the parallels among the couples; the visiting novelist Maude Mockridge says in the film that Charles and Ann should marry and complete the perfect symmetry set up by the “snug” pairings of the two other couples.

In the course of the first night’s exposures, hidden parallels are brought to light. Ann is mutely in love with Robert, who is mutely in love with Betty. Both the Freda-Robert marriage and the Gordon-Betty one are revealed as loveless. In the play, more parallels are piled on: Both Freda and Gordon have Martin for a lover, while Charles keeps Betty as his mistress.

Since parallels invite us to note contrasts, we can see that Phil Rosen (never accorded the status of an auteur) has somewhat altered things during the replay portion of the climax. Some variations in framing mark the second version as different from the first.

Mostly the purpose of the new angles in the replay is to highlight Charles and Ann, preparing us for their romantic alliance on the patio. The first version makes them small and far off-center left; the second emphasizes them much more, with the high angle enlarging and centering their flirtatious encounter.

My two last principles are also borne out in the film version of Dangerous Corner. One says that the last path traced presupposes the others. By that I mean it can take the earlier iterations as already read.

One result is that later versions of events can presented more briefly. When an alternative reality runs through bits we’ve already seen, we don’t need to see the full original version. This happens in the second fork of the film, which takes less than three minutes to get us to the crucial split—when Gordon discovers the fresh radio tube and tunes in the dance music. The first iteration of the evening’s events took almost five minutes to get us to the same point. This may seem a minor difference, but such intervals matter in a movie whose action consumes only sixty-two minutes on the screen.

Moreover, one time-saving passage shows the importance of the first iteration as setting up the situation. In the first version, Maude the novelist inquires about Martin, and she bends over a portrait photo of him.

This shot is less for her than for us, introducing the character whom we’ll see in Ann’s flashback. During the second version, we don’t get the full discussion between Maude and Freda, and we aren’t shown the photo. The narration assumes that after the flashback Martin is vivid enough in our memory. What replaces the insert of Martin is a reverse shot of Freda, describing Martin.

Now that we know she was Martin’s mistress, we’re in a position to appreciate how her dialogue and expressions conceal their relationship.

Similarly, the first version stresses the cigarette box that Ann inadvertently says she recognizes. The second version contents itself with a long shot, because now no one will question her about it.

The sense that the last path we see presumes the others has a more interesting side effect. Sometimes we get the sense that in the last go-round the character is mysteriously aware of the other paths she or he has taken. This happens in Sliding Doors and Run Lola Run, when each heroine seems to have learned from her experiences in the parallel worlds. And multiple-draft films like Groundhog Day and Edge of Tomorrow make this learning process essential to the action. The premise is illogical, but narratives often violate logic.

Something similar happens in the film (but not the play) of Dangerous Corner. Alone with Charles on the patio, Ann accepts his marriage proposal because the cigarette box she saw at Martin’s, now in Freda’s hands, made her realize she’s “been a fool.” We have seen the flashback in which she fought off Martin and accidentally killed him. The flashback isn’t in the play, and it’s especially interesting because presumably that scene really did take place, in both paths. That is, the evening orgy of confessions is one hypothetical alternative, but the manner of Martin’s death a year before, revealed in this path, is an actual event. It’s as if reliving Martin’s attack during the first path has made Ann appreciate Charles’s genuine love for her.

My seventh principle also bears on the last path we encounter. It’s a simple one: We take the final path as the correct one. Since endings are typically the place where all is revealed, we’re prepared to accept the last reiteration as what really happened. (This can be reinforced by a character’s learning curve, such as Ann’s.) Dangerous Corner is a good example.

I think we’re urged, by the second intertitle but also by the overall arrangement of the parts, to see that the quiet maintenance of civility predominated during that evening. The more sordid alternative, though given at much greater length, is what’s under the surface but what will never be acknowledged. The truth of the theft and Martin’s death, along with all the love affairs and animosities spilled out in the first version, will never be brought to light.

Other factors give the second version more weight. There are the shots I mentioned that stress the Ann-Charles relationship more, but for me the clinchers are more structural than stylistic. For one thing, both Ann and Charles play the role of raisonneur–the character(s) who explains the action and articulates central themes of the piece. In both the first path and the second, Ann echoes Priestley’s notion of our limited knowledge, saying that we prefer half-truths to the complete, factual account, the one that only God knows. And in both paths Charles warns against telling the truth, as it presents a “dangerous corner” that could lead to a smash-up. No other characters reflect so fully on the consequences of letting everything out.

Another structural factor involves the film’s beginning and the ending. The 1933 section starts with a scene in which Charles calls on Ann and once more asks him to marry her. Thanks to the primacy effect, this pair of characters becomes more salient in what follows than the married couples do. As a result, the epilogue, set on a terrace like the first one, harks back to the indubitably actual, pre-fork opening.

The fact that the movie ends with the creation of a couple, the uniting of the two characters who are the most self-aware and sympathetic throughout the film, reinforces the sense that this is the “real” outcome.

I hope you’ll read the whole essay. My purpose is to understand the dynamics of a small but increasingly common body of films. Forking-path films ask us to construct stories in unusual ways, but we quickly learn what guidelines to follow. Once the format exists, filmmakers take up the challenge of mastering it, stretching it, applying it to new material. (Edge of Tomorrow was sometimes considered Groundhog Day Goes to War against Aliens.) As filmmaking practice develops, we can track contemporary experiments and relate them to earlier efforts they are based on.

In addition, it’s worth knowing that a fairly sophisticated filmic treatment of the format appeared eighty years ago. In the essay, I find even earlier examples. And in a period when every movie seems at least 130 minutes long, it’s nice to encounter one that offers so much narrative complexity in about half that running time.

More generally, I think that probing this body of film shows the value of systematically studying narrative formats of any type. We’re used to talking about genre as a fluctuating body of conventions, but we should also study conventions that cross genres—conventions of story worlds, plot structure, and narration. These conventions can prod us to execute some unusual mental moves. Filmmakers are practical psychologists, and they’ve learned how to tease and tickle our minds. What-if movies are just one example of how norms and forms guide our understanding of story.

My first quotation from Priestley comes from Three Plays and a Preface (Harper and Brothers, 1935), ix. The second comes from Two Time Plays (Heinemann, 1937), ix.

In production, Dangerous Corner seems initially to have replaced Priestley’s what-if premise with more of a whodunit plot, while incorporating subjective sequences. According to a Variety review of an 83-minute cut before release, the explanations offered for Martin’s death by the various men are followed by something fairly unusual.

Surprise and twist, with increasing suspense, are accomplished through a shift from the factual elements to subjective processes on the part of the three women most closely related–as wives or sweethearts–with the suspected men. An innocent revolver shot precipitates the terrific speculations as each woman wonders if her man has killed himself in an adjoining room (Daily Variety, 13 September 1934, p. 3).

By the final release, however, the film had lost twenty minutes, and the result was the version we have. I haven’t seen versions of the screenplay, but I bet they’d be interesting. We’re left with other what-if questions, this time about the production of the movie itself.

Some of the basic concepts I employ here and in “Film Futures” are explained in the essay “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” online here. That essay is in turn applied to The Wolf of Wall Street in this blog entry.

Dangerous Corner (1934).

Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics

DB here:

In The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!, 1951), Howard Tyler has drifted into crime under the guidance of a breezy sociopath. They commit a string of holdups, culminating in a kidnapping. Howard’s partner bashes in the skull of their young captive. Wandering drunk and despairing, Howard ends up in the apartment of Hazel, a lonely manicurist. As Howard lolls on the sofa, she turns away to switch off the radio.

The next move is up to us.

If we’re alert, we can spot, on the end table in the corner of the frame, a newspaper with a headline that may be announcing the police investigation.

At first Hazel takes no notice. Will she? She does. She lifts the paper and is appalled.

Hazel turns toward Howard. Now we can see the entire headline as she reads aloud: Police are intensifying the search. She hasn’t made the connection between her guest and the boy’s disappearance.

Panicked, Howard lunges at her and crumples the newspaper.

Will this display of shattered nerves tip Hazel off?

As in the bomb-under-the-table model of suspense, at the start we know more than both characters know. She’s unaware of the kidnapping, and he’s unaware that the cops have found the victim’s car. In addition, the arc of suspense around the headline is quite small, though it leads on to something larger: Will Howard give himself away to the unsuspecting Hazel?

I’m impressed by the economy of presentation. Hitchcock might well have treated this moment in point-of-view shots, and a fairly protracted series of them. Or imagine how several filmmakers today would have handled this scene. There’d be a slow a track-in to the headline, then a circling camera movement that first concentrates on the woman picking up the paper, then racks focus to Howard on the sofa in the background.

Instead, director Cy Endfield makes very small changes of framing and staging matter a lot. The camera simply swivels, the actress simply comes to the foreground and pivots. The entire action, crucial as it will prove in what follows, consumes only twenty-five seconds.

Some stretches of a movie tend to be simply, barely functional: connective tissue or filler. Shots show cars driving up to places where the real action will take place, or characters striding down a corridor before going into a doorway. Other images want to engage us more deeply, but they do it through immensity. They try to awe us with majestic swoops over the sea or into the sky. (Recent example: Interstellar.) But other films engage us through detailing. They train us to notice niceties.

The Sound of Fury moment creates its detailing through visual space. What about time? And what about auditory factors? Our old friend, the telephone call, can furnish some examples.

Number, please

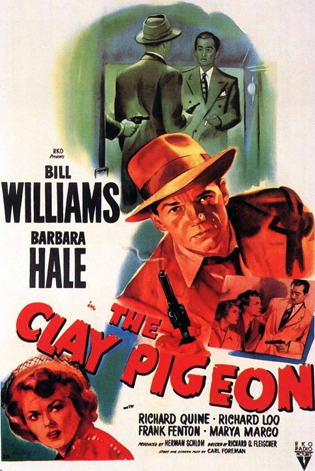

Clay Pigeon (1949).

Filmmakers must always decide how much of any action to show. Sometimes that allows the director, the cinematographer, and the editor to create fine-grained delays. These might not build up a lot of suspense but they can make us uneasy, and prepare us for a surprise later down the line.

As we mention in Film Art, and discuss in a related blog entry, a telephone scene forces the filmmakers to choose among clear-cut alternatives. Do we see both parties? Do we see only one and simply hear the other? (And is the voice of the one we don’t see futzed?) Do we see one and not hear the other at all? Most films don’t ask more than simple functionality, but even a B man-on-the-run feature like The Clay Pigeon (1949) shows what can be done with details of timing in setting up a phone call.

Jim Fletcher has war-related amnesia. He doesn’t know why he’s about to be court-martialed for treason. After escaping from the hospital, he learns that he is accused of betraying his best friend during their time in a Japanese POW camp. After convincing Martha Gregory, the friend’s widow, that he’s innocent, he searches for proof. The Clay Pigeon sticks mostly with Jim, but like most suspense films it slips in bits of unrestricted narration as well. Jim’s quest is tracked by mysterious men, and brief scenes give us glimpses of the forces pursuing him: agents of Naval Intelligence, and a gang of counterfeiters protecting the Japanese soldier who tortured Jim in the Philippines.

It’s the familiar structure of the double chase, dosed with minor mysteries. For example, when Jim gets a lead from a management firm, he leaves the office but the narration stays with the secretary who notifies her boss that Jim has been asking questions.

Cut to the executive’s office, where the camera reveals many stacks of wrapped bills on his meeting-room table. Something sinister is going on here, but what?

The decision to insert information addressed to us alone has more subtle consequences in two telephone scenes. Jim calls Ted Niles, another veteran of the POW camp. During these scenes, the filmmakers had the option of showing only Jim and never revealing Ted at the other end of the line. That tactic would have enhanced mystery, but it would have thrown suspicion on Ted. If he’s Jim’s friend and ally, why not show him?

So the filmmakers show Ted replying in his apartment. But later it will be revealed that Ted is working with the gang. The task is to introduce this important character in a way leaving open the possibility of his treachery. The solution the filmmakers hit upon is to show Ted just before he picks up the line. Here is the first instance, when Jim cold-calls him.

The camera shows Ted innocuously answering the phone and learning, to his surprise, that Jim has tracked him down.

At first Ted seems annoyed, but then he smiles and agrees to help.

The scene ends on Jim hanging up. If we wanted to plant more suspicion of Ted, we’d show him hanging up too and reacting to the call.

A later scene starts much the same way, with Ted coming in to answer a ringing phone and getting a message from Jim.

Both scenes show Ted answering the phone in a completely innocuous way. Yet the very fact of dwelling on his action of coming to the phone can be seen as planting uncertainty. In the second scene, for instance, where is he coming from? And in both scenes, Ted frowns at certain points. Perhaps he is pondering ways of helping Jim, but the expressions leave open the possibility that he is plotting against him. Ted’s duplicity is fully revealed only at the climax. (See image surmounting this section.)

In a mystery situation, a few seconds showing Ted alone gain a force they wouldn’t have in another genre. Some viewers will be surprised, some will say they knew it all along, but either way the detailing of a moment here and there has opened the possibility.

Party line

The Clay Pigeon telephone scenes show the speakers in alternation. The give-and-take of the conversation is presented by cutting back and forth. Another option is simply to show one speaker and let us hear the other without seeing him or her. As we’ve noticed, though, that would tend to make Ted a more mysterious figure.

Yet another possibility is the silent treatment: One speaker is shown talking, and we don’t hear the other at all. This option forces our attention wholly onto the reaction of the person we do see, and keeps us in the dark about the words and tone of voice of the person at the other end of the line. If the Clay Pigeon telephone calls presented Ted this way, that would be another tipoff.

Still, suppressing one half of the conversation can pay dividends when we already know the characters. At the climax of Humoresque (1947), detailing involves not a prop or a passing moment. Instead, a simple cut accentuates the shift from one sound space, that of violinist Paul Boray’s dressing room, to another, the luxurious living room of his lover Helen Wright. When he gets her call, he can’t understand why Helen isn’t at his big concert. But she is distraught because her own worries about keeping Paul’s love have been reinforced by Paul’s mother, who insists that she’s no good for him. And Helen is drinking again.

The scene’s tension is ratcheted up by first presenting only Paul’s angry questioning. We don’t hear Helen’s replies. When the dramatic momentum shifts to Helen’s desperate excuses for missing the concert, we concentrate on her meltdown more intently because now we don’t hear Paul’s replies. Her emotional response is magnified by the yearning climax of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture on the radio broadcast–another reason to suppress Paul’s voice.

The scene has been split between Paul’s end and Helen’s. By not seeing Helen’s reaction to his urgent questions, we wonder what is keeping her away. Like Paul, we’re unaware of her torment. But then we see and hear her, and our inability to know what he’s saying makes his pleas seem ineffectual. Whatever he’s saying doesn’t seem to matter. A simple speaker/listener cut raises the scene to a new pitch, which will build still further when we follow Helen out onto the terrace. One more detail, brutal: We don’t hear Paul’s voice, but we do hear the click when he hangs up.

One thing that links all these Little Things: What the filmmakers did not do. Cy Endfield did not indulge in camera arabesques or POV cutting. Richard Fleischer and his colleagues did not suggest Ted’s duplicity with music or a noirish shadow. Jean Negulesco and company didn’t yield to the temptation to crosscut furiously between a panicked Paul and an anguished Helen. These directors did something rare today. They presented the situation with stylistic simplicity. That way the big moments–the revelation of Ted’s treachery in the train, the frenzied mob in The Sound of Fury, the all-enveloping climax of Helen on the beach–become more vivid. Big things need little things to seem bigger.

Thanks to Jim Healy, who introduced me to The Sound of Fury and The Clay Pigeon.

For more on the bomb under the table, see the followup entry here.

Lest someone think I’m dumping on Nolan, let’s just note that he can, when he wants, summon up niceties. (By the way, thanks to readers for hustling to our Nolan vs. Nolan entry, but they should read the one on The Prestige and our Inception series here and here to get a fuller sense of our estimation of him. All of these are put into reader-friendly order in an insanely inexpensive ebook…..)

Several other blog entries consider detailing in performance: Henry Fonda’s hands, Bette Davis’s eyelids, and the facial expressions in The Social Network. I’m still mulling an entry on eyebrows, which are terribly underrated. For another Joan Crawford tour de force, there’s this.

Humoresque (1947).

Bread, circuses, and Oscar buzz

Kristin here:

A little over a month ago, Entertainment Weekly posted a story about this year’s Oscar bait. It began in a surprising way:

It’s September, so why wouldn’t we start predicting an Oscar race that won’t finish for another five months?

To be fair, Venice, Telluride, and the Toronto film festivals have all concluded. Many films have screened. Many films have connected with audiences, and a rough draft of the Oscar race is beginning to come into focus. Sure, no Academy member will even begin popping in those screener DVDs for another couple of months, but it’s still worth discussing what has buzz and what is likely to still be on voters’ minds once the weather finally begins to cool off.

Here’s a very early look at what the race looks like now.

This wouldn’t have been surprising in a comparable story, say, five years ago. But in the last few years we have somehow gotten into a nearly half-year-long cycle of what is now invariably called “Oscar Buzz.” Why does Entertainment Weekly need to justify printing such speculation in September when every other remotely entertainment-related venue is already doing it?

Just as David and I avoid printing ten-best lists at the end of the year (apart from our surprisingly popular series on ten-best films of 90 years ago), so we avoid speculating on Oscars, Golden Globes, BAFTA, or Toronto awards. It’s hard, however, to avoid seeing this kind of speculation when it’s all over the internet and fills the pages of trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter.

This increasingly obsessive coverage isn’t merely annoying. It has significant consequences. One egregious effect has gotten more common over the past two or three years: a new tendency to treat film festival programming as indicating what might be nominated for big awards. Now journalists routinely treat big festivals as competing with each other, not for the most intriguing films but for the big award bait.

Maybe some festivals do compete in this way, but the coverage is certainly encouraging such behavior. Still, these festivals also show a lot of other films–more obscure ones that might be more interesting and which the public should know about. The more “Oscar buzz,” however, the less attention paid to smaller films.

David and I tend to think of festivals as an alternative distribution and exhibition circuit. That circuit makes available films that won’t come to your local multiplex, or even your local arthouse. Those of us who are devoted to movies of a wide range of types go to festivals to catch up on world cinema, as opera devotees travel to cities that have opera houses and festivals. But there are signs that some festivals are starting to cater to the glitz of awards-friendly films and red-carpet events, and we fear that others may follow suit.

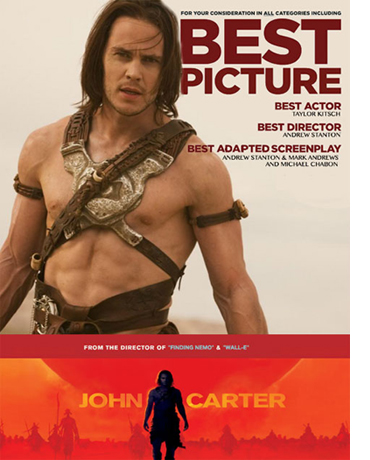

For your expensive consideration

Oscar buzz is great for the trade journals. Even those who don’t subscribe to them know about the “For your consideration” ads that pop up, glossy and  usually covering a full page of the large-format Variety and Hollywood Reporter–sometimes a two-page spread. These ads used to come out mainly before the Oscar nominations were being voted on, but now the season has expanded, and any vote-based awards show provides occasion to run them. A new practice is to run additional magazine ads in the weeks after the awards shows as well, congratulating the winners. Such ads used to be mainly taken out by the production studio and/or distributor, but now talent agencies, professional guilds, and other organizations will run such ads, listing all their clients, members, and employees who have been nominated or have won awards.

usually covering a full page of the large-format Variety and Hollywood Reporter–sometimes a two-page spread. These ads used to come out mainly before the Oscar nominations were being voted on, but now the season has expanded, and any vote-based awards show provides occasion to run them. A new practice is to run additional magazine ads in the weeks after the awards shows as well, congratulating the winners. Such ads used to be mainly taken out by the production studio and/or distributor, but now talent agencies, professional guilds, and other organizations will run such ads, listing all their clients, members, and employees who have been nominated or have won awards.

Of course, awards-related ads generate revenue for print magazines in a time when the internet is luring away readers. Part of the expansion of “for your consideration” ads has been promoted by the journals themselves. If they publicize more films as potential Oscar nominees, the studios will want to, or at least feel pressured to take out ads for films that they might not otherwise think were plausible nominees. They also have to keep their talent happy. If a star gets a lot of Oscar buzz in the media, he or she might begin to expect the studio to run such ads, whether or not the buzz is based on any real likelihood of a nomination.

Oscar buzz is also great for filling of column inches or composition panes with text that costs very little to generate. Reviewers have to be sent to festivals so they can see the latest films, and they go armed with expense accounts. As long as they’re there, why not have them write about Oscar buzz as well? They’ve already seen the films, written their reviews, and perhaps interviewed some of the talent. Writing about Oscar buzz is easy and based on chitchat and speculation. It’s presumably a lot cheaper to run such stories than to have a reporter spending a lot of time tracking down information for a hard-news item about business trends in the industry.

It’s also easy, since if a writer is just speculating, he or she can’t be wrong. Nobody will go back after the Oscars and blame an author for not having predicted a nominee correctly. If most of the infotainment press had predicted the wrong winner, they can generate drama by writing about a “surprise” winner to make up for it. And since a consensus often quickly develops among reviewers and commentators about who will be nominated, a lot of people are making pretty much the same predictions anyway. If they’re wrong, they won’t be the only ones.

Another advantage that Oscar buzz offers film reviewers has occurred to me. It’s a minor but pretty pervasive one. Acting is a hard thing to describe, beyond making some sort of enthusiastic remark about someone being superb in a role or an actress totally losing herself in a part. But if you just say, “Steve Carell generates Oscar buzz for his role in Foxcatcher,” you’ve given it the highest form of praise and haven’t had to describe it. The same thing can be done with directing, design, cinematography, and musical scores.

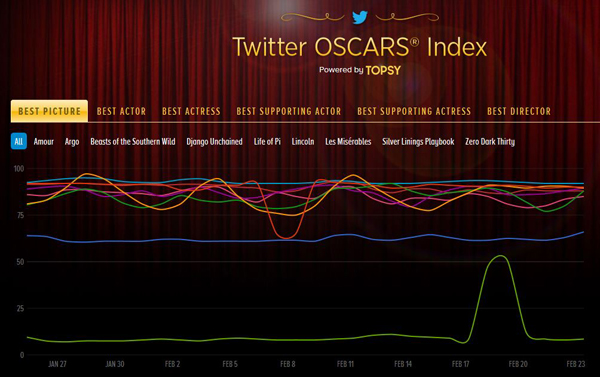

The buzz spreads

Oscar buzz doesn’t just pervade trade-press coverage, fan sites, and infotainment media. The same buzz ripples out through all levels of publication, and that’s true of the coverage of festivals as early indicators of award-worthiness. Online sites are scrambling at all times to draw attention, and anyone can speculate about what might get nominated and win, even if they don’t go to the big “buzz” festivals. The public seems to have an endless appetite for this stuff.

People Magazine, which did send at least one reporter to Toronto, posted a story entitled “All the Oscar Buzz (Reese! Eddie! Jen?) from Toronto.” The author is pretty straightforward about her interest in the movies she saw: “The second half of the festival delivered big-time, adding powerhouse performances and major A-list Oscar buzz to the mix. Here’s some of what we discovered … start planning your fall moviegoing and Oscar pools now!”

Even National Public Radio, which does run more serious stories on cinema, broadcast an interview with critic Bob Mondello and blogger Linda Holmes, called “Oscar Buzz Builds at Toronto.” Reporter Robert Siegel, who was not himself at the festival, knew from previous buzz just what questions he should ask, as with this: “Now, the Toronto Film Festival is one place where Oscar buzz begins for actors. Let’s talk about a few performances. First, Steve Carell in the movie Foxcatcher.” One might imagine asking instead, “Toronto is a place where new talent is discovered. Have you seen any foreign films or intriguing American indies with amazing performances by unknowns?” But that would not be, as People would say, “major A-list Oscar buzz.”

I mentioned that the buzz is more than just annoying and distracting. One has to wonder if such relentless speculation becomes self-fulfilling. After all, people in the film industry read the trade papers and the popular press. In the case of the Oscars, it’s industry professionals who do the nominating. For the Golden Globes, it’s a small number of entertainment-press people, and they are self-evidently aware of what’s being buzzed about. Despite all the talk of diversity in filmmaking being made possible by digital technology and the rise of indie distribution options, the coverage in mainstream journals doesn’t deal much with non-mainstream efforts. Among all this buzz, there is some speculation about nominees for the foreign-language category, but that, too, tends to involve familiar names. If Asghar Farhadi has a new film out, it will inevitably be mentioned in Oscar buzz, but would an equally good Iranian film by a newcomer get the same attention? Maybe from a few reporters, but not with the uniformity of opinion with which the prominent films are treated.

To most readers, however, the foreign-language category is of minor concern, and Oscar buzz is largely confined to big Hollywood releases and the most prominent of independent films. At best, indies are included as “other possibilities” in prediction lists. Ann Thompson, for example, divides her “Oscar Predictions 2015 Update” lists into three categories: “Frontrunners,” “Contenders,” and “Long Shots.” I guess the idea now is that just to be nearly nominated for an Oscar is honor enough for a worthy film that is realistically speaking not Oscar bait. Am I being too cynical in thinking that it’s also a way to include more possible names and hence increase one’s chances of being right about some?

Premieres and galas

Indiscriminate Oscar buzz is pretty familiar by now. But during the last year or two another notion has emerged. There’s a push to define big film festivals most importantly by the fact that they spotlight awards-worthy films. These festivals are said to be competing, not for good films, but for titles that will capture award nominations.

Justin Chang has recently traced how the stress on Oscar-buzz titles arose within the festival community. In his late-August article, “Telluride vs. Toronto: The Battle for Oscar Supremacy,” Chang points to the shifting policies of the big festivals. This year Toronto instituted a new policy: only films making their world or North American premieres would be screened during the first four days of the festival. This tactic sought to counter Telluride’s advantage of taking place shortly before Toronto. (This year Telluride ran August 20 to September 1, Toronto September 4 to 14.) The new policy apparently arose from the fact that in previous years Telluride, despite running far fewer films than Toronto shows, had managed to screen more Oscar-winning titles.

Festivals have always competed for major films and for premieres, and whether Toronto’s change of policy was directly tied specifically to the Oscars may be up for debate. It might instead be that the press perceives it that way because of commentators’ new emphasis on festivals as Oscar predictors. Perhaps it’s a little of both. Clearly, however, journalists now perceive this competition as hot subject matter for Oscar buzz. Scott Feinberg entitled one article on Telluride for The Hollywood Reporter, “Telluride: Benedict Cumberbatch Leads Weinstein’s ‘Imitation Game’ into Oscar Fray.” Variety’s Tim Gray, whose official title is “Awards Editor,” also reported from Telluride: “Reese Witherspoon’s ‘Wild’ Premieres to Oscar Buzz in Telluride.” An article on CinemaBlend bears the forthright title, “Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game Win The Telluride Battle for Oscar Buzz.” This sort of coverage pressures the festivals to move further in this direction. Who wants their festival to be reported as having lost the battle for Oscar Buzz?

Festivals have always competed for major films and for premieres, and whether Toronto’s change of policy was directly tied specifically to the Oscars may be up for debate. It might instead be that the press perceives it that way because of commentators’ new emphasis on festivals as Oscar predictors. Perhaps it’s a little of both. Clearly, however, journalists now perceive this competition as hot subject matter for Oscar buzz. Scott Feinberg entitled one article on Telluride for The Hollywood Reporter, “Telluride: Benedict Cumberbatch Leads Weinstein’s ‘Imitation Game’ into Oscar Fray.” Variety’s Tim Gray, whose official title is “Awards Editor,” also reported from Telluride: “Reese Witherspoon’s ‘Wild’ Premieres to Oscar Buzz in Telluride.” An article on CinemaBlend bears the forthright title, “Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game Win The Telluride Battle for Oscar Buzz.” This sort of coverage pressures the festivals to move further in this direction. Who wants their festival to be reported as having lost the battle for Oscar Buzz?

As Toronto already has been. The website Sight on Sound has a regular column, “The Hype Cycle,” which runs during “awards season” and has a daily summary of awards speculation. In one entry, “Toronto, Telluride and Venice Oscar Buzz (Part 1),” we read:

The Toronto International Film Festival’s People’s Choice Award has been one of the most reliable barometers for both Best Picture contenders and winners, having recently recognized Slumdog Millionaire, The King’s Speech, Silver Linings Playbook, Precious and 12 Years a Slave.

This year however, Toronto may have gotten the short end of the stick compared to its contemporaries in Telluride, Venice and the upcoming New York Film Festival. And it remains to be seen whether any of these titles can make for a plausible, formidable or least of all permanent frontrunner. Let’s take a look at this week’s rankings.

In sum, coverage of Oscar buzz is easy to generate. Trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, however, are becoming a lot less useful to industry professionals and to film enthusiasts when they devote so much space to the same sort of speculation going on in the popular press. These journals’ subscriptions are costly, and yet between the awards coverage and the articles on expensive real estate, restaurants, and fashions, they contain far less solid industry news than they used to. In the long run, is this approach beneficial to readers and the journals themselves?

Still, there is a benefit to the festivals to have at least a few high-profile films which potentially could be nominated for awards. For one thing, simple box-office. Festivals depend on ticket sales for part of their income, and the more obscure fare doesn’t bring in as many customers as those high-profile ones.

Beyond that there are the patrons. Big donors like the glamor of red-carpet events. At the parties after the major screenings, they get to schmooze with the famous and talented. Companies that act as sponsors like to have their brand associated with prestigious films–and no doubt their officials also like to schmooze with stars. The big films get prime treatment (evening slots, biggest auditoriums, opening and closing galas), even though those same films, like Wild and Foxcatcher, are often the ones soon to be released theatrically.

Most festivals have far more films in their programs than the few high-profile ones, and most programmers do attempt to show a wide range of films, including documentaries, local films and foreign films unlikely to be picked up for wide distribution. To stress the competition for few buzzy films and ignore the rest does a disservice to us all.

One other effect of linking of Oscars to the big festivals of the early autumn is to further disadvantage good films released earlier in the year. Commentators have long lamented the fact that potential Oscar nominees released early tend to be forgotten by the time the nominations are made. There are occasional exceptions, with The Silence of the Lambs (released in February, 1991) being the usual example cited. Variety‘s Tim Gray recently speculated on whether Academy members will keep The Grand Budapest Hotel and Boyhood in mind when making out their nominating ballots.

True, the Academy may need reminding of Grand Budapest, which came out in late March. But Boyhood was released in mid-July, only a month and a half before Telluride. If Gray is right that it has already receded from the minds of Academy members, then the cluster of big festivals starting with Telluride forms a major cut-off point that downplays films released in the first eight months of the year. The Oscar-buzz coverage in the wake of the big August-September-October festivals tends to create the impression that the “awards season” is just beginning, and that the best-received films that premiere there and the ones that are released during the big holiday season are the ones that will be nominated. As Gray points out, all the best-picture nominees of 2013 were films released in the last three months of the year.

It would seem logical for the studios to be displeased at this effect. After all, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is an organization founded and supported by the biggest Hollywood production/distribution companies. At least in recent decades, the main functions of the Oscars are to publicize films and to bring in a large sum of money for the television-broadcast rights. The latter supports the Academy’s other, less well-known activities, like lobbying and film preservation. Sure, Oscar buzz is great publicity for the few titles that receive it. But if eight months’ worth of worthy films are increasingly treated as inconsequential, that’s not good for business. So far, however, the Hollywood producers don’t seem to be doing much to remind Academy members of the older releases. So far the main tactic used to remind Academy members of older films is to hold special screenings with talent present for Q&As. Such events obviously reach only a small portion of the widely scattered membership.

Are there advantages for a big festival that avoids competition for likely award films? A report on the New York Film Festival in Variety, “NY Film Fest: Less Risk, More Reward for Studios,” suggests that there are:

From a distributor’s perspective, NYFF can sometimes be a smart choice since there are no awards, and coming later in the season, less chance for negative buzz to build on potentially divisive end-of-year releases. “It’s a safer but well-respected festival,” says one distribution exec. “It’s a good litmus test for a film, without the risk of everything blowing up in your face. If it plays well, you can put more into (marketing) it.”

The story’s author spoke with the festival’s director, Kent Jones, who plans to stick to a program based on quality films. He “stresses that while he’s not opposed to the occasional sale, there will be ‘no marketplace,’ and ‘business and curation won’t get mixed up.'” The piece concludes, “And if the fest wars continue to heat up, a less competitive NYFF just might end up as a more attractive option for filmmakers looking to stay out of the fray.”

Samuel Fuller, or Jean-Luc Godard, said that “Cinema is a battleground,” but I don’t see why film festivals should be.