Archive for 2014

Middle-Eastern fare at VIFF

Winter Sleep.

Kristin here:

Iranian cinema moves on

Maybe it’s just the particular selection of Iranian films at this year’s festival, but I sensed a shift from the ones we’ve seen in previous years. Last year I titled one of my entries “Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to Viff.” This year familiar names are missing, including Kiarostami, Panahi, Rasoulof, and Farhadi. (Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s new feature, The President, was at Venice but not here at VIFF.) Moreover, all three of the Iranian fiction features this year depart from some conventions we’ve grown used to in the New Iranian Cinema of the past decades.

Whether A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) is actually an Iranian film is debatable, though it is listed as such in the program. Its director, Ana Lily Amirpour, was raised in England and subsequently moved to the USA, where she studied filmmaking at UCLA. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is her first feature and has American backing (including Elijah Wood as one of several executive directors) and was shot in California. Amirpour is of Iranian descent, and the film is in Farsi, which may be enough to have it considered Iranian.

It’s hard to imagine, however, such a film being made in Iran. It’s a vampire film, taking place in an imaginary town called Bad City, perhaps located in Iran but perhaps not. Its setting look distinctly like the less picturesque parts of the American West:

Amirpour has fashioned a remarkably good pastiche of an American widescreen, black-and-white genre film of the late 1950s or early 1960s, as this image and the one at the bottom of this entry demonstrate. As the Variety review points out, the look is also informed by graphic novels, notably Sin City. Indeed, this summer Amirpour has published a brief graphic novel with the same title as her film; it’s apparently a prequel to the movie’s story. Given that it is labeled #1, the artist presumably envisions a series.

The genre is the vampire film, though this one is hardly conventional. The vampire is the Girl of the title, and the director has taken amusing advantage of the resemblance between her triangular black hijab and the classic floor-length cloak worn by screen vampires, such as that of Bela Lugosi in the 1931 Dracula:

The heroine moves eerily through the streets of the town (see bottom), picking as her victims men who have exploited women. A romance develops between her and a more sensitive young man, clearly modeled on James Dean.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night played at Sundance and has been picked up for American Distribution by Kino Lorber, apparently with an October release planned.

The two other Iranian films are what David has dubbed “network narratives.” One is straightforwardly so, the other far less so.

Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Tales (2014) in some ways develops on the classic quest narrative of so many Iranian classics since the 1980s, where hero or heroine (often a child) doggedly set out to accomplish something, with the struggle laid out in detail. In Tales the questing characters are multiplied, with their paths crossing and sometime re-crossing.

Unlike in most of the earlier films, these quests don’t always yield results, and hence closure. The characters are mostly involved in seeking help of some sort, sometimes from other people, sometimes from a government institution. The cumulative effect is to suggest a society that has lost the ability or the will to respond, even to desperate pleas.

The film begins with a filmmaker riding in a friend’s cab, shooting the passing cityscape. He immediately drops out of the story, though he will return. Ironically, the story’s action begins with a failed attempt to help someone. The cab driver is hailed by a prostitute with a sick child. Recognizing her as an old friend of his family’s, he buys medicine and a toy for the child, only to find that the woman has disappeared into the night.

Arriving home, he tells his mother of this encounter. We then follow her in a scene in an office building, where she tries to fill out a form complaining about not having received her pension. A gentleman in the corridor helps her, and we follow him into a meeting with a petty bureaucrat who takes calls from his wife and mistress, ignoring what the man is trying to tell him.

A central scene returns to the mother, now on a bus of protestors. The same filmmaker whom we saw at the opening is making a film about their personal plights. We watch through the viewfinder as the mother pleads for help. It’s not clear whom the film is aimed at or who will eventually see it. Later in Tales, the filmmaker remarks that all films eventually get seen, but this seems far too vague to hold out much hope for those caught in a maze of bureaucratic red tape and neglect.

The network structure reportedly resulted from the fact that under the Ahmadinejad regime Bani-Etemad could only get a license to make a series of shorts. Subsequently she was able to weave these together into a feature.

Bani-Etemad, who also produced Tales, is considered Iran’s top female director. Here she brings back some characters from her earlier films, including Dr. Dabiri, from Gilaneh (2005), and Sarah, from Nargess (1992). The VIFF program quotes her as saying, “Tales returns to the characters of my previous films under today’s circumstances.”

Finally there is Fish and Cat (2013), which elicited mostly praising reviews when it debuted in Venice. (For an example, see our friend Alissa Simon’s take on it for Variety.)

Despite running a lengthy 134 minutes, director Shahram Mokri shot the entirety as one lengthy take, without benefit of CGI. A sinister mood is set up immediately when a title hints that it will concern some restaurant owners in a remote district who may have used human flesh in their meat dishes. Two owners of the restaurant are introduced in the opening scene, and we follow them as they set out on a path through the nearby woods, carrying weapons, tools, and a bag soaked in what looks like blood:

The pair chat until their path crosses that of Kazim, a young man participating in an annual kite-flying event to take place by a nearby lake; he’s trying to ditch his clinging father. We follow him to the lake, then leave him to latch onto Parviz, who is trying to organize the young people arriving for the event. And so it goes, until eventually the brief scenes between the people who meet and part begin to repeat, but from a different vantage point. Much of the action involves the camera tracking with the characters from behind, as in the frame above, resulting in an occasional difficulty in identifying whom we’re watching.

The tone remains ominous throughout, with the two thugs and a third accomplice intruding at intervals, perhaps with murderous intentions. There’s also plenty of dark humor as well, and despite the slow unrolling of the action, the film remains absorbing throughout. Some viewers will be tempted to see the film on DVD/BD again, trying to work out the complicated looping chronology of the plot–possibly diagramming it, as the filmmakers presumably had to.

Those who can’t do

We wrote about Israeli director Nadav Lapid’s first feature, Policeman, in our 2011 VIFF report. This year he is back with his second, The Kindergarten Teacher (2014).

The film is a psychological study of young woman, Nira, who is an apparently ordinary and devoted kindergarten teacher. She learns that one of her small charges, Yoav, a shy, uncommunicative five-year-old boy, has an odd habit. Occasionally he begins to pace back and forth, declaring “I have a poem” and then reciting a short poem that would do credit to an adult author.

Nira’s reaction to this apparent prodigy is shifting, occasionally ambiguous, and increasingly disturbing. We are confined almost entirely to what she observes and does, so we get no other view of Yoav except when his nanny and father talk with Nira.

Initially she seems inclined to take advantage of Yoav. We witness her reciting one of his poems as her own at a poetry-writing group that she attends. This premise is soon dropped, however, when Nira takes Yoav under her wing. She favors him over his classmates and encouraging his artistic impulses. Eventually she tries to take control of him, clearly picturing herself as gaining reflected glory from being a mentor to a great artist.

Given the limited point of view, we are encouraged to speculate as to how Yoav comes up with his poems and how far Nira will go in crafting the triumphant public career that she clearly wants for the boy. When she discovers that his boorish, business-minded father has no use for poetry, she increasingly tries to control Yoav, taking him to a public poetry-reading and getting him to recite onstage:

Cumulatively the film traces a slow and disturbing path toward her greater obsession. A subtly presented clue suggests the nature of Yoav’s recitations–to us, that is, if we catch it. Nira misses it, or chooses to ignore it.

Once again in Anatolia

Three years ago we wrote about Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once upon a Time in Anatolia as one of our favorite films of the 2011 VIFF. Now Ceylan is back with another long film, Winter Sleep (2014), and again it stood out among the films we saw this year.

The film was shot in the Cappadocia region of Anatolia in central Turkey. The area is a major tourist attraction, with caves, “fairy chimneys” and other spectacular stone formations, rock-cut chapels, and structures from antiquity.

The protagonist, Aydin, is an ex-theater actor now retired and running a hotel made up partly of rooms cut into the picturesque rock formations. It’s the winter season, with only a Japanese couple and a motorcycle devotee staying at the hotel, and Aydin has plenty of time to write columns for the local paper and bicker with his young wife Nihal and embittered, recently divorced sister Necla:

This time there is no crime investigation or mystery around which the plot centers. Instead the narrative is a character study, played out partly in long conversations between Aydin and the two women. There are also scenes in which Aydin reacts with indifference to the sufferings of his impoverished tenants.

The early part of the film is given over to Aydin, who at first seem mildly sympathetic, brilliant and creative. But as he converses with Necla in a lengthy central scene in his study, his remorselessly sardonic sister picks apart his flaws in a verbal duel between two equally witty characters. Later, Nihal feels beaten down by Aydin’s opposition to her charitable work, the only activity that gives her satisfaction in this isolated life, and she finishes the job of exposing Aydin’s selfishness.

The program notes compare the film to the plays of Chekhov, and there is a definite similarity, both in the conversations and in the contrasts between the wealthy family and the working-class people who resent being dependent upon them. Despite the fact that much of the film consists of long conversation scenes–and runs for 196 minutes–the large, sold-out audience with whom we watched the film were dead silent, clearly captivated by the story. Unlike Chekhov, in the end the film offers a glimmer of hope for the characters.

Ceylan has said that he shot in the distinctive landscapes of Cappadocia only reluctantly:

I actually didn’t want to use it, but I had to. I originally wanted a very simple, plain place, but the film had to be set in a tourist area, and I needed a hotel that is a little isolated, outside of town. Cappadocia was the only place I could find that in the winter time still had tourists.

I was afraid of shooting in Cappadocia because it might have been too beautiful, too interesting. But I didn’t show it too much, I hope.

Ceylan succeeded, I think. There are enough shots of the rock formations to impress us, but they are used sparingly. One might interpret the landscapes as reflections of the characters’ inner turmoil, in much the way that Maurice Stiller and especially Victor Sjöström used Scandinavian landscapes in their classic films of the 1910s and 1920s. (See top, where Aydin pauses to think near some rocky outcroppings.)

It certainly shows enough that Winter Sleep might cause a rise in tourism among art-cinema audiences. One hotel’s blog has already mentioned the film as a way of luring customers.

Winter Sleep won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year and will receive an “awards-season” release in the USA by Adopt Films.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Here be dragons, and tigers

Revivre.

DB here:

My first visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival back in 2005 was at the invitation of Tony Rayns, programmer of the Dragons and Tigers series. That series included both new films by established directors and a batch of first or second features by beginners. Tony asked me to be on the jury for the young D & T award.

I enjoyed working on that jury, which consisted of old friend Li Cheuk-to of the Hong Kong Film Festival and new friend Gerwin Tamsma of the Rotterdam fest. We gave the prize to Liu Jialin’s Oxhide, and it’s been gratifying to track her career since. In the course of my stay I realized what an excellent festival Vancouver had, not least because of the warmth and enthusiasm of its staff.

My Vancouver experience helped launch this blog, which really got under way during my second visit, in several entries in 2006. That was also the year I met Bong Joon-ho, who was at VIFF with The Host. I kept going back, and Kristin began joining me, so every year we’ve been writing about this admirable event.

During that 2006 festival Tony decided to rearrange his commitment to Dragons and Tigers. He turned the curating of Chinese-language films over to expert programmer Shelly Kraicer, who was living on the mainland and had excellent contacts within China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Now things have changed again. This year the festival accepted fewer beginners’ features and folded them into a broader international competition. One of the Asian films in the collection, Rekorder by Mikhail Red, tied with a French entry, Miss and the Doctors, for the award. In the old days, the winner received a cash prize; alas, that benefit has not been retained, but maybe some far-sighted patron will step forward to give the award a little more heft.

There were fewer D & T titles overall this year, but I still found several of great interest. Herewith some notes on them.

Time, and time again

Revivre.

If your movie is going to include flashbacks, you have a choice among several standard ways of motivating them. You can use the very old device of presenting an investigation or trial, in which the film translates testimony into dramatized scenes. Or you might frame the flashbacks with a scene of a character who thinks back on events in the past. Three of the Dragons and Tigers films used some other common flashback setups, but treated them in fresh ways.

Im Kwon-taek’s Revivre (Hwajang, his 102nd film!) starts with another canonical flashback situation. In fairly washed-out footage a funeral procession crosses the screen. A man at the head of the group looks back and sees a beautiful young woman looking gravely at him. Immediately the film triggers questions: Whose funeral is this? Why is the young woman important?

The rest of the film fills us in via flashbacks,. The protagonist, Oh Sang-moo, is a manager of the advertising section of a cosmetics company. His wife is stricken with a brain tumor and he cares for her as best he can during her years of surgery and recovery. At the same time, he develops a restrained affection for Ms. Choo, an employee in his division. Eventually Oh’s wife dies and there is the lingering possibility of his starting his life afresh with Ms. Choo, whose phantom face we’ve seen in the procession. Threaded through this are the pressures of a business deadline, his need to keep his staff on track, his occasionally fraught relations with his daughter, and his wife’s adamant insistence that after she dies he keep none of her things, not even her beloved dog.

The film scrambles the order of Oh’s experiences. After the funeral, within about five minutes we get a scene of Oh’s wife dying in the hospital, then a scene of his own medical problems, and then the moment that Oh’s wife collapsed in the garden, yielding the first sign of a tumor. The rest of the film gives us incidents from all phases of their last years together, with emphasis on his careful attention to her bodily functions. Although his daughter finds the task repellent, Oh changes his wife’s diapers and cleans her private parts with the same calm professionalism that he brings to the meetings in his company. In all, the non-chronological flashbacks work effectively to show Oh juggling the pressures of business with the demands of his family situation.

What makes Im’s treatment a little unusual is that the flashbacks aren’t presented as Oh’s memories. They are rearranged by the narrational authority of the film itself, rather than by situations that provoke Oh to recall this or that incident. We’re restricted to Oh’s range of knowledge throughout, but that doesn’t draw us closer to him. We have to read his mind through his expressions and his gestures, and these are often severely controlled. A master of the poker face, this executive keeps a polite distance from everyone, including the viewer. Is he one of nature’s stoics? Or is he emotionally detached, attending to his dying wife more out of duty than love?

These questions are partly answered by some brief fantasy scenes in which Oh visualizes Ms. Choo as a romantic partner. She seems to intuit his interest, and responds through small signals. When she starts to reciprocate more explicitly, Revivre returns to its mood of impassive sadness for its final scenes.

Time and freedom

Hong Sangsoo has been playing with time from the start of his career. He has tried replays from different viewpoints (The Power of Kangwon Province, 1998), replays that differ in details (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 2000), odd déjà-vu experiences (Turning Gate, 2002), and all manner of theme-and-variations plotting (as noted on this blog here and here and here). So it’s a bit surprising to find him exhuming the old reliable setup of letters recounting events in the past. Yet here as ever he has a couple of tricks up his sleeve.

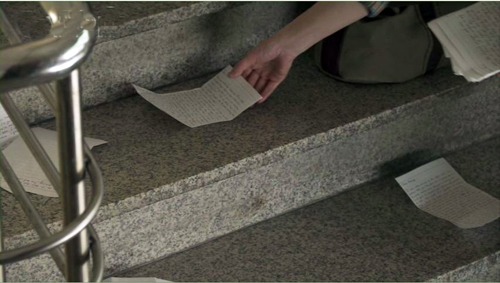

Like Im, Hong has scrambled the flashbacks in Hill of Freedom, but he offers a comically exact motivation. Kwon, a young language teacher in Seoul, returns to find a sheaf of letters written to her by a Japanese admirer, Mori. He taught with her at the school two years earlier. He has come to Seoul to reunite with her, and he has left her a letter every day. She starts to read them in the school lobby, and Mori’s voice-over narration establishes the beginning of his story. He tells how he found lodging, left a note at Kwon’s apartment, and paid his first visit to the “Hill of Freedom” café.

So far, 1-2-3 preparation. But when Kwon starts to leave the language institute, she staggers on the staircase, as if stricken, and scatters the letters on the steps. She gathers them back up in random order. This sets up the scrambled timeline of the flashbacks to come. (Hong mischievously zooms in on a letter she fails to retrieve, hinting at a gap in the story that will follow.)

What Kwon learns, in mixed-up order, is that Mori’s search for her leads him to meet and hang out with his landlady’s nephew, while also becoming romantically involved with Youngsun, the café owner. In the grip of a possessive lover, Youngsun attaches herself to the fairly passive Mori. Their affair plays out in Hong’s usual mix of drinking bouts and pillow talk.

By the time we’re used to this pattern, Hong sets up a new game. As he keeps cutting back to Kwon reading through the letters, accompanied by Mori’s voice-over, Hong gradually reveals that she is reading them in the Hill of Freedom café—the very place Mori hoped to meet with her (but never did).

Eventually, Kwon steps outside for a cigarette, and we suddenly get her voice-over remarking that the last letter was postmarked a week ago. Has Mori then already left and stopped writing? At this point Kwon encounters Youngsun coming in, and they greet each other as friendly acquaintances. The next scene finds Kwon visiting Mori’s guest house.

What happens there shifts the ground under our feet. After talking with friends, I think that we can’t be sure about what’s actually taking place. A mysteriously bruised cheek, a surprise reunion, and the return of Mori’s voice-over fill the penultimate scene. The coda is even more of a puzzler, at least to me. (I wonder if it’s the scene described in the letter that Kwon didn’t retrieve.) In any event, Hong’s usual themes of the foolish arrogance of Korean men and the comedy of male-female interactions are given new expression in this lightweight but enjoyable movie. The fact that Hill of Freedom is mostly in English, which Mori must employ to communicate with the Korean characters, adds to the fun.

Video virus

Yet another trigger for a flashback can be provided by a crisis situation. It might be rather near the story’s climax, so that we are left hanging and the plot takes us back to the origins of the problem. This is what we get in movies like The Big Clock (1947), which starts with our hero hiding out from the police and wondering how he got in this pickle. Or the crisis situation may come earlier in the story, with the flashback again filling in what led up to it before continuing the situation presented in the frame.

This latter option is followed in Mikhail Red’s Rekorder. After a brief prologue showing violent acts captured by CCTV cameras, we are in a police van with stern cops chatting about killing a dog before we’re introduced to the shaggy, wasted protagonist Maven riding with them.

From this framing situation we flash back to the reason Maven is in the van. Once a cinematographer in the glory days of Filipino cinema, he’s now a loner using his ancient camcorder to film movies in theatres and sell them to a friend who bootlegs DVDs.

Maven is a compulsive recorder. As the director puts it, he is “a ghost in the city observing everything through his lens.” So naturally he’s filming when a street gang kills a young man in front of a crowd who simply watch. Maven doesn’t volunteer his footage, since it includes part of a movie he was pirating. But now he’s been nabbed and is riding to headquarters with the cops, who are very curious about what’s on his tape.

Much of the rest of the film involves Maven’s attempt to keep the cops from examining his footage, while he agonizes about his passive acceptance of street violence. There are still more flashbacks, appropriately presented through old video footage of his wife and daughter. Not until the end of the film do we witness–again, on CCTV footage–the trauma that has turned him into the burnt-out case he is.

Mikhail Red commented that he was inspired to make Rekorder by a viral video in which a youth was shot in the street by thugs and a big crowd didn’t intervene but instead filmed the murder. He staged his own CCTV-style video to supply the denouement, and was shocked to find that it was appropriated in documentaries about street crime. Through a multimedia format, Rekorder updates the sort of social criticism that Raymond Red, Mikhail’s father, brought to Filipino cinema of the 1980s. That era as well is evoked through another sort of flashback, the clips from classic movies that Maven films. “I wanted,” Red says, “to pay homage to the pioneers.”

Straight time

You don’t need to play time tricks to create an uneasy movie. Ow (Maru) presents a typical family squeezed by Japan’s economic stagnation. Dad pretends to have a job, when he actually sets out each day for the unemployment office. Mom and grandma putter about. Grown but spacy Tetsuo lounges about his room talking baby talk. One day, when his girlfriend has just snuggled into bed with him, they are transfixed by a big gray-brown sphere that drifts into his room.

Transfixed, literally. They freeze upon seeing it. So does Dad, and so do the cops who are called. Director Suzuki Yohei introduces us to the big ball with a shot of it slowly spinning, held long enough for us to get slightly hypnotized too. There follows some comic suspense in which people enter the bedroom and may or may not leave. The biggest tease is the reporter who, after learning of a death during the sphere’s arrival, researches the case and then lunges into the room, ranting about a police cover-up.

The tension–will others fall under the spell or the sphere?–is accentuated by shrewd camera setups. When the cops arrive, we get a low-angle shot behind Yuriko and Tetso, showing the frozen cops and a new one not yet transfixed. He pushes one stiff colleague over, revealing the ball, still hovering there, and we wait for him to be the new victim.

Much later, when the reporter first visits the room, the sphere has vanished. But a rhyming angle forces us to remember its presence, and to let the reporter–the source of the plot’s momentum for the rest of the movie–take the place of the hapless cop.

Finally, for another exercise in unkinked time, there is the Korean action picture Haemoo. Produced by Bong Joonho, it centers on the desperate captain of a fish-trawler who agrees to bring illegal immigrants into Korea. Everything that could go wrong does: storm, fog, Coast Guard patrols, a horny crew, and an idealistic novice seaman who tries to protect a woman. Everything, including the accident that creates a horrifying midway turning-point, is carefully prepared in the film’s opening scenes. The film’s second half locks us into the relentless consequences of covering up a huge crime.

The pace is so snappy that I expected lots of cutting, but I counted only about eight hundred shots in 106 minutes. (The Equalizer, only twenty minutes longer, has three times that number.) I attribute this cutting rate to neatly functional direction, with no fuss or waste. The ship’s engine room is a cramped set, hazy with steam and dust, and the shots there are finely calibrated to build the drama through depth, fluid camera movement, and our old friend The Cross. The randy engineer’s business of checking the equipment carries him from one side of the shot to the other, while the young seaman shifts around him–first on frame right, then on frame left, then in the center.

The plot has that satisfying neatness that is characteristic of Bong’s work, and its forward thrust has no need of flashbacks. We can’t ask for backstory when the upcoming twists are as fast-paced and exciting as they are here. Dragons and Tigers has always showcased not only the experimental films like Ow and Hill of Freedom but also the crowd-pleasers, and Haemoo (which translates as “Sea Fog”) solidly fulfills that mission. Long live linearity!

Hill of Freedom has sharply divided critical opinion. Richard Brody considers it a masterpiece; others consider it fluff. At Fandor David Hudson painstakingly surveys the cut and thrust of the controversy.

Hill of Freedom.

The World comes to Vancouver

The Golden Era.

Kristin here:

One of the great pleasures of the Vancouver International Film Festival is the ability it provides for a quick trip around the world, especially to countries whose films are seldom seen in a non-festival setting.

In one day I was able to see an Algerian film and one from the Ivory Coast. It struck me that both of them reflected how far digital filmmaking has come in small producing countries. When digital cameras came on the scene, they were hailed as a way for people in nations with little or no filmmaking infrastructure to create movies. The results, fascinating though they might be, often betrayed visually the fact that they were made with non-professional cameras.

Perhaps we have reached a new stage in digital filmmaking in such countries. Both the Algerian film, The Rooftops (Merzak Allouache, 2013), and the Ivory Coast one, Run (Philippe Lacôte, 2014), have a polish and complexity of form and style that put them on a level with those made in larger, more established national cinemas.

The Rooftops provides a model of how to make a film with a limited budget and avoid conventionality. Allouache chose to set the film entirely on the rooftops of five districts of Algiers. It’s a gimmick of sorts, and yet it carries practical advantages. No sets had to be built, and few, if any scenes required artificial light. Presumably no streets had to be cleared, since no action is staged at ground-level.

Beyond that, each scene could be played out with the city of Algiers providing a backdrop, as when a group of young musicians practice on one of the rooftops:

With backgrounds like that, who needs sets?

The film has a strict formal logic, both spatially and temporally. It begins by introducing five rooftops, each with its own set of characters. There’s no crossover among the groups. None of them ever meet, so this isn’t what David has termed a network narrative. But the look of each rooftop is different, and simply by keeping the characters in one limited area, the filmmakers help us keep track of them fairly easily as the narrative moves among storylines.

The film starts with the first call to prayer in the darkness before dawn, and at intervals the four other calls follow (with a subtitle providing information on the name of each call and the time period within which the respective prayers are supposed to be performed.) These essentially act as chapter breaks, giving a sense of time passing. The five prayers also echo the five rooftops.

There’s no shortage of drama in each group’s story. On a lower floor of an unfinished building a mob boss has a man tortured, trying to force him to sign something. This disturbs a group of filmmakers taking shots from the roof above, with dire consequences. A landlord is murdered on another rooftop, and a suicide occurs on yet another. One gets a cumulative impression of crime and conflict being rife across these various districts of Algiers.

Allouache is considered the preeminent Algierian director, and the violence and strife depicted rather melodramatically are part of his ongoing critique of his nation’s social problems.

In contrast, Lacôte sets Run apart by adopting a classic flashback structure. The film opens with the crisis of the story: the hero, nicknamed “Run,” shoots the prime minister in a crowded auditorium and flees.

From then on, we see him in hiding as he reflects on how he became an assassin. The alternation of scenes from his youth and his current-day attempts to avoid capture are easily comprehensible. Lacôste finds ways to create visual interest and avoid conventional stagings of scenes, as in the low angle above that juxtaposes the hero with a looming, crisscrossing ceiling.

Another example comes when his friend gives him shelter and food. Rather than a simple shot/reverse-shot conversation across a table, we see a depth scene, with Run sitting on the floor to eat and his friend in the foreground twisting to talk with him:

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, the notion was that people in underdeveloped countries could gain small cameras and discover their own ways of making films, free of Hollywood conventions. To some extent that happened. But with the globilization of mass media, few people, however isolated, can remain unaware of Western culture.

Presumably some filmmakers have aspired to match the technical standards of Western offerings in international film festivals. These two films show them succeeding, having thoroughly grasped the conventions of both art films and popular genres. We ‘ll discuss an example of the latter in an upcoming entry on Middle-eastern films at VIFF, and in particular the Iranian vampire film, Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Ann Hui’s quiet epic

Ann Hui’s career is usually associated with intimate films, mostly studies of character. We saw her at Ebertfest earlier this year, where she presented A Simple Life, the epitome of such films.

Now she has surprised audiences with another character study, but one set in a tumultuous period of Chinese history, the late 1930s and early 1940s. The Golden Era (2014) tells the story of female writer Xiao Hong, who died young in 1942. Not all the facts of Xiao Hong’s life are known, and the narrative sketches scenes derived from the author’s own writings. Interspersed are “documentary” shots of interviews with people (played by actors) who knew and worked with Xiao Hong.

Much of the tale consists of small-scale scenes, conversations among a few people set indoors or in the streets. Yet as the Japanese invasion begins and spreads, occasional big scenes occur, and Hui proves herself perfectly capable of suggesting creating a sense of epic events.

The war is only fleetingly present, however. We see it mainly from the viewpoint of the main characters, as when a quiet indoor conversation scenes are abruptly and startlingly cut short by bombs going off outside and shattering windows.

The film’s settings and costumes create a vivid sense of the era. There are street scenes in Hong Kong shortly before its fall to the Japanese that appear almost documentary in their realism. Throughout the images are beautiful, as the frame at the top of the entry demonstrates.

The film’s three-hour running length adds to the epic feel, tracing the heroine’s changing fortunes across momentous historical events. It makes a striking contrast with A Simple Life, and yet Hui’s concern with precision and detail in delineating characters remains constant. The pair might bring her back to the sort of prominence outside Hong Kong that she enjoyed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Indeed, The Golden Era was just presented as the gala film at the Busan Film Festival.

Another farewell from a Ghibli master

Just over a year ago Miyazaki Hayao announced that he would retire, having completed and released his final film, The Wind Rises (2013). Speculation over the fate of Studio Ghibli, the animation studio that he co-founded, followed.

Now we have the reported final film of a second of the three original founders, Takahata Isao, whose most famous film is Grave of the Fireflies (1988). Like The Wind Rises, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2014) lets its director go out on a high note.

Based on a tenth-century fairy tale, Princess Kaguya has a distinctive style, with most scenes done in translucent watercolors in pastel shades, quite different from the solid, vivid colors of much of Miyazaki’s work. It tells its story in a leisurely fashion, running 137 minutes, which may be a bit challenging for younger children, but it is never boring.

Kaguya is not necessarily a princess. We’re not sure what she is. She appears miraculously one day as a tiny baby in a glowing bamboo shoot. She is iscovered by a bamboo-cutter who assumes she is a princess and insists on calling her that. The bamboo-cutter and his wife raise her in a forest cottage (seen below). The opening section is idyllic, with the tiny girl growing unnaturally fast, in spurts. She is befriended by neighboring children, and the group explores the surrounding countryside, reveling in the beauty of the plants and animals they observe there.

Spurred by another miraculous discovery, this time of gold nuggets inside a bamboo stalk, the bamboo-cutter decides to build a mansion in a nearby city and make Naguya into a real princess by marrying her off to royalty. There ensues the classic competition among suitors to find the most fabulous object and present it to Naguya.

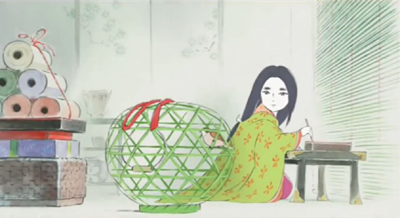

Naturally Naguya longs for the countryside and finally rebels. In a remarkably stylized, exciting scene that contrasts with the rest of the film, she races toward her forest home, and the pastel settings disappear. She becomes a blur of black, white, and red flashing through a gloomy landscape with sketchily drawn trees and plants that flicker wildly past:

The Tale of Princess Taguya has been announced for an October 17 release in the USA, distributed by GKids. Unfortunately it will only be available in a dubbed version. Even dubbed, it’s worth seeing on the big screen, but with luck there will be an option for the original Japanese-language version with subtitles on the DVD/BD release.

Studio Ghibli has released another film, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a documentary about the studio by Sunada Mami. (It played at Toronto but is not here at VIFF.) Its appearance seems to hint that Ghibli really is going to cease feature production, though the official story is that it is only pausing. It has been a prolific producer of short animated films, and perhaps that side of its activities will continue. For a good summary of the situation and a description of the documentary, see here.

The Tale of Princess Taguya

Of horses, avalanches, and architecture

Of Horses and Men (2013).

DB here, with some first impressions of this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival.

We alternate days of rain and days of sunshine, but crowds still keep turning up. Some screenings are packed full, and most of those we’ve visited are solidly attended. Herewith some notes on three of the most intriguing movies I’ve seen so far.

The getting of wisdom

La Sapienza (2014).

The last Eugene Green movie I saw was The Portuguese Nun, which I discussed in a 2010 entry. His latest, La Sapienza, is more user-friendly, somewhat closer to American art-house accessibility.

A married couple in a politely disintegrating relationship takes a trip to Italy, and then their paths diverge. Alexandre, a famous architect who conducts research on the side, takes along on a field trip the young Goffredo, who wants to be an architect as well. Aliénor, a psychoanalyst, stays with Goffredo’s sister Lavinia, who suffers from fainting spells. Each character comes, by a quiet path, to a degree of peace and reconciliation. Alexandre even renews his creative energy, thanks partly to Goffredo, who insists that architecture is not only about space but what fills it: Light and people.

As ever with Green, everybody is gorgeous; the clothes are casually splendid; the backgrounds are magnificent. Threaded through La Sapienza is overwhelming architecture (Turin, San Carlino, Rome), accompanied by Alexandre’s discussion of Francesco Borromini’s career. The climax, a muted one, takes place in the Chapel of San Carlo, filmed in appropriately radiant majesty. In a way, the movie is a fine art-history class.

Crosscut with the two men’s journey are the ministrations of Aliénor to Lavinia, who comes out of her shell when shown kindly attention—and exposure to the theatre. (Le Malade imaginaire, no less.) Green is one of the few filmmakers today who makes movies in homage to the pleasures of aesthetic experience. No wonder that one of his films has the title Le Pont des Arts. But he’s not completely highfalutin. One scene makes fun of pretentious contemporary artists, chiefly to throw the purity of classic art into greater relief.

Green’s signature staging and cutting are still in force; he offers a sort of parodic simplification of analytical editing’s progression of master-shot, over-the-shoulders, and singles. Given these familiar patterns, we quickly get used to the artifice of to-camera address, sometimes in extreme close-up. Viewers who admire Wes Anderson’s style should check out Green’s more austere handling of planimetric imagery.

Most American studio pictures allot a separate shot for each character’s line, and Green does much the same, but his pace never seems as rushed. I think it’s partly because of the pauses between lines, which allow us to wait for more from the speaker, or to anticipate how the listener will react.

All in all, another piece in that cloisonné mode that Green has made his own. But La Sapienza has freshness because of its new subject matter. We get not a romance among young people but a fading love among their elders. The film harks back to a great tradition of disenchanted couples visiting alien places, from Voyage to Italy to Certified Copy. And the actors, particularly Christelle Prot as the wife, have an intelligent vivacity. Alexandre’s demeanor and expressions, robotic in the opening scenes, warm and relax across the film as he comes to enjoy visiting Borromini’s sites and learning from his young companion. The film exemplifies what Alexandre describes as one building’s integration of human bodies and rigorous patterns: “Living figures in geometrical constructions.”

A Nordic problem play

Another film about a couple’s troubles while they’re away from home is Force Majeure, a new Swedish film with the original title Turist. Tomas and Ebba seem to have a fine upper-middle-class family, with beautiful kids Vera and Harry. Seeking quality time, they arrive at a high-tone ski resort in the French alps. They have a pleasant visit at first, punctuated by the cannons that trigger controlled avalanches, until one such snow slide seems to threaten them on a patio. Tomas’ reaction puts their marriage in question, and Vera and Harry become fussy and scared. Tomas comes to see the family crisis as the collapse of his male identity.

As with the Green film, people talk a lot. In the great tradition of Nordic drama and Bergman psychodrama, what we’ve been shown must also be discussed, and the past dredged up, and bystanders dragged into intimate crises. The central scene, in which Ebba presses Tomas to explain himself in front of another couple, runs by my count over twelve minutes. Its painful but riveting drama drifts into satire when Tomas’ intellectual friend tries to find evolutionary explanations for what happened.

Unlike the Green film, Force Majeure is the opposite of austere. Even without the breathtaking scenery, the ski lodge is given a sort of ersatz grandeur itself. And the big moments swallow up speech in sumptuous visual effects, most obviously the avalanche but also an eerie scene that appears to record a flying saucer’s surveillance of the lodge. The spectacle doesn’t stop in the coda, a vertiginous bus ride that leaves issues of courage and family unity uneasily suspended.

Horse whisperers, and shouters

According to reports, John Ford once remarked that a running horse is the most beautiful thing in the world. There’s some evidence for the claim in Of Horses and Men, an Icelandic film about life in a valley among horse farmers. It’s composed of episodes of local life, sometimes trivial and sometimes life-or-death, taking place across a summer.

The locals let much of their stock roam across the valley until they herd them into a corral for the winter. The massive roundup, spiced with some sexual shenanigans, forms the film’s climax, with majestic shots of galloping horseflesh. The final crane shot celebrates the vastness of the herd against the stupendous landscape, while giving it human scale with an ambling musical score reminiscent of Morricone’s lighter tunes.

So this is not your standard hardscrabble-life-in-distant-places film. Granted, the neighbors, a scruffy lot given to passing around flasks and snuff, are attractively cranky and realistically unpretty. None would get an audition for Eugene Green. But their petty quarrels, as when one rancher keeps snipping the barbed wire that another rancher keeps stringing across a thoroughfare, become comic (though some lacerations are involved). Particularly hilarious is the scene of a rancher so devoted to drink that he goads his poor steed to swim out to meet a Russian fishing boat carrying lethally strong alcohol.

What a pleasure to meet a movie that tells its story visually! Details of behavior matter. The ritual of bridling a horse gets carried out in ways that characterize the riders, and there is one moment, in which a young woman accomplishes the apparently impossible, that is crowd-pleasing without being over the top—all presented briskly and with hardly any dialogue.

Another laconic scene takes place after the credits. A lantern-jawed rancher proudly steers his trotter to breakfast with a neighbor woman. Director Benedikt Erlingsson introduces other major characters by showing them in their yards watching the gentleman’s ride. In turn, he learns they’re watching by catching the glint of sun on their binoculars.

This bit of routine suggests what passes for entertainment among these nosy folks. It also becomes a running gag, so that in later scenes, as soon as we cut to the horizon and see the telltale flash, we know someone’s eyeing the action. This sort of pictorial economy, rare in today’s films, eliminates exposition and lets us think we’re smart.

In fact, the act of looking becomes a persistent motif, as most episodes are introduced by a screen-filling close-up of a horse’s eye, with humans or landscapes reflected there. It’s as if these beautiful beasts are quietly observing their masters’ foibles.

Kino Lorber will distribute La Sapienza in the United States, Magnolia will do the same with Force Majeure, and Music Box Films will be offering Of Horses and Men.

La Sapienza.