Archive for 2014

ADIEU AU LANGAGE: 2 + 2 x 3D

Adieu au langage (2014).

DB here:

Godard’s Adieu au Langage is the best new film I’ve seen this year, and the best 3D film I’ve ever seen. As a Godardolater for fifty years, I’m biased, of course. And I might feel that I have to justify taking a train from Brussels to Paris to watch it (twice). But the film seems to me superb, and it gets better after several more (2D) viewings.

People complain that Godard’s movies are hard to understand. That’s true. I think they provide two different sorts of difficulty. He lards his dialogue and intertitles with so many abstract (some would say pretentious) thoughts, quotations, and puns that we’re tempted to ask what he is implying about us and our world. That is, he poses problems of interpretation—taking that to mean teasing out general meanings. What is he saying?

I think that this type of difficulty is well worth tackling, and critics haven’t been slow to do it. Scholars have diligently tracked the sources of this image or that barely-heard phrase. Adieu au langage provides another field day; there are movie clips, some quite obscure, and citations (maybe some made-up ones) to thinkers from Plato and Sartre to Luc Ferry and A. E. van Vogt. Ted Fendt has discovered a massive list of works cited in the film, and even his list, he acknowledges, is incomplete.

I confess myself less interested in interpretive difficulties. I don’t go so far as my friend who says, “Godard is a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher.” But I do think that he uses his citations opportunistically, scraping them against one another in collage fashion. In particular, I think that by having characters quote, quite improbably, deep thinkers, he’s trying for a certain dissonance between the abstract idea and the concrete situation.

What situation? That brings us to the second sort of difficulty. It’s often rather hard to say just what happens, at the level of plot, in a Godard film. From his “second first film,” Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), “late Godard” (which has lasted over thirty years, much longer than “early Godard”) has made the story action quite hard to grasp. Oddly enough, most reviewers pass over these difficulties, suggesting that story actions and situations that we scarcely see are fairly obvious. (Reviewers do have the advantage of presskits.)

The brute fact is that these movies are, moment by moment, awfully opaque. Not only do characters act mysteriously, implausibly, farcically, irrationally. It’s hard to assign them particular wants, needs, and personalities. They come into conflict, but we’re not always sure why. In addition, we aren’t often told, at least explicitly, how the characters connect with one another. The plots are highly elliptical, leaving out big chunks of action and merely suggesting them, often by a single close-up or an offscreen sound. Godard’s narratives pose not only problems of interpretation but problems of comprehension—building a coherent story world and the actions and agents in it.

We ought to find problems of comprehension fascinating. They remind us of storytelling conventions we take for granted, and they push toward other ways of spinning yarns, or unraveling them.

Case in point: Adieu au langage.

Since the film will be appearing in the US this fall, under the title Goodbye to Language, I want to encourage people to see this extraordinary work. But I’m also eager to talk about it in detail. So here’s my compromise, a four-layered entry.

I’ll start general, with some sketchy comments on some of Late Godard’s narrative strategies. In a second section I make some speculative comments on Godard’s use of 3D. No real spoilers here.

Then I’ll offer an account of the opening fifteen minutes. If you haven’t yet seen the film, this section might be good preparation. But part of experiencing the film is feeling a bit at sea from the start, so this section might make the film more linear than it would appear on unaided viewing. You decide how much of a preview you want.

The last section briefly surveys the overall structure of the film, and it is littered with spoilers. Best read it after viewing.

Spoilers notwithstanding, nothing stops you from eyeing the pictures.

Ecstasy of the image

Film Socialisme (2010).

Much in Adieu au langage is familiar from other Godard films. There are his nature images–wind in trees, trembling flowers, turbulent water, rainy nights seen through a windshield–and his urban shots of milling crowds. All of these may pop in at any point, often accompanied by fragments of classical or modern music. Again he returns to ideas about politics and history, particularly World War II and recent outbreaks of violence in developing countries. His standard techniques are here too. The film begins before, and during, the credits, which appear in brusque slates often too brief to read. Music rises, often just enough to cue an emotional response, before being snapped off by silence or an abrasive noise.

In his narrative films, as opposed to the collage essays like Histoire(s) du cinéma, we get scenes, but those are handled in unusual ways. He tends to avoid giving us an establishing shot, if we mean by that a shot which includes all the relevant dramatic elements. He often has recourse to constructive editing, which gives us pieces of the space that we are expected to assemble. Although Godard’s early films relied on this a fair amount, it became pronounced in his later work, where he tweaks constructive cutting in unusual ways. I discuss one example here.

Often we get an image of one character but hear the dialogue of an offscreen character. And the shot of the lone character may hang on quite a while, so that we wait to see who’s speaking. By delaying what most directors would show immediately, Godard creates, we might say, a stylistic suspense. I can’t prove it, but I suspect the influence of Bresson, who said to never use an image if a sound will suffice.

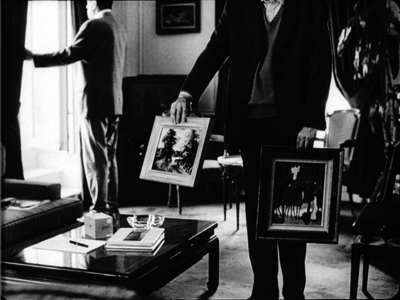

When Godard doesn’t give us unanchored close-ups or medium-shots, he may do something more drastic. A signature device of his later work is the shot which stages its action in ways that make the characters hard to identify. He may shoot in silhouette (Notre musique, 2003).

More outrageously, he may frame people from the neck or shoulders down (Bresson again?) and make us wait to discover who they are (Éloge de l’amour).

Such decapitated framings are disconcering, since orthodox cinema highlights faces above all other body areas. When we can’t access facial expressions, then the dialogue, gestures, postures, and clothes become very important. Godard can, of course, combine these strategies (below, Éloge de l’amour; also the Film Socialisme image above). In this shot, the man standing in the background is an important character but we never see him clearly.

Godard’s opaque “establishing” shots may be very condensed and laconic; he jams in a lot of information, partial though it is. In one shot of Adieu au langage, a dog approaches a couple on a rainy night and the woman urges her partner to take him in. All we see, however, is the man gassing up the car (and we don’t see him all that clearly).

We hear (dimly) the dog’s whimpering and the woman’s plea, but we see neither one.

Godard frets and frays his scenes in other ways. He creates ellipses, time gaps between shots that may leave us uncertain. What happened in the interval? How much time has passed? He also interrupts the scene through cutaways to black frames, objects in the scene, or landscapes; the scene’s dialogue may continue over these images, or something else may be heard.

At greater length, the scene can open up onto a digression, a collage of found footage, intertitles, or other material that seems triggered by something mentioned in the scene. In Film Art: An Introduction, we argued that one alternative to narrative form is associational form, a common resource of lyrical films or essay films. Godard embeds associational passages in his narratives, the way John Dos Passos embedded newspaper reports in the fictional story of his USA trilogy. Sometimes, though, the associations are textural or pictorial. At one point in Adieu au langage, Godard associates licked black brushstrokes on a painting with churned mud and the damp streaks on the coat of the dog Roxy.

By fragmenting his scenes, Godard gets a double benefit. We get just enough information to tie the action together somewhat, and our curiosity about what’s happening can carry our narrative interest. But the opaque compositions and the bits and pieces wedged in call attention to themselves in their own right. Blocking or troubling our story-making process serves to re-weight the individual image and sound. When we can’t easily tie what we see and hear to an ongoing plot, we’re coaxed to savor each moment as a micro-event in itself, like a word in a poem or a patch of color in a painting.

But those images and sounds can’t be just any image or sound; they hook together in larger patterns that sometimes float free of the plot, and sometimes work indirectly upon it. The best analogy might be to a poem that hints at a story, so that our engagement with the poetic form overlaps at moments with our interest in the half-hidden story.

Where, some will ask, is the emotion? We want to be moved by our movies. I suggest that with Late Godard, we are mostly not moved by the plot or the characters, though that can happen. What seizes me most forcefully is the virtuoso display of cinematic possibilities. The narrative is both a pretext and a source of words and sounds, forms and textures, like the landscape motifs that painters have used for centuries. From the simplest elements, even the clichés of sunsets and rainy reflections, the film’s composition, color, voices, and music wring out something ravishing.

We are moved, to put it plainly, by beauty–sometimes exhilarating, sometimes melancholy, often fragmentary and fleeting. Instead of feeling with the characters, we feel with the film. For all his exasperating perversities, Godard seeks cinematic rapture.

3D on a budget

The smallest set of electric trains a boy ever had to play with? Photo: Zoé Bruneau.

Most of the 3D films I’ve seen strike me as having two problems.

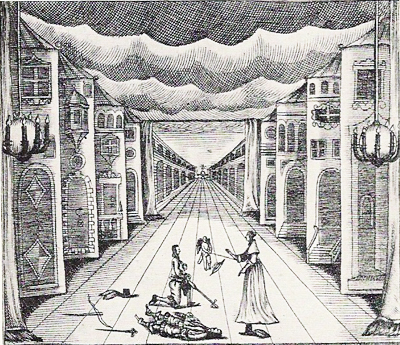

First, there is the “coulisse effect.” Our ordinary visual world has not only planes (foreground, background, middle ground) but volumes: things have solidity and heft. But in a 3D film, as in those View-Master toys, or the old stereoscopes, the planes we see look like like cardboard cutouts or the fake sections of theatre sets we call flats or wings (coulisses). They lack volume and seem to be two-dimensional planes stacked up and overlapping. Here’s an example from a German stage setting of 1655, with the flats painted to resemble building facades.

In cinema, the thin-slicing of planes seems to me more apparent with digital images that are rather hard-edged to begin with. (3D film was more forgiving in this respect.) Sometimes the flat look can be quite nice, as in Drive Angry (2011). In this action sequence, the planes prettily drift away from one another, with no attempt to suggest realistic space.

Apart from the coulisse effect, there’s the problem that the 3D impression wanes as the film goes along. I’ve long thought it was just me, but other viewers report perceiving the depth quite strongly at the start of the movie and then sensing it less after a while, and maybe not even noticing it unless some very striking effect pops up. Part of this is probably due to habituation, one of the best-supported findings in psychology. Maybe, as we get accustomed to this fairly peculiar 2.5D moving image, it becomes less vivid.

More than our perceptual habituation might be at stake. Filmmakers may reduce depth during certain scenes to save money on postrproduction effects. Some gags in A Very Harold and Kumar 3D Christmas (2011) rely on old-school, smack-in-the-eye, paddle-ball depth, but much of the middle of the film doesn’t employ it. By tipping up the glasses and checking how much displacement is in the image, I’ve been surprised to find that remarkably long stretches of 3D films have little or no stereoscopy.

My impression is that Adieu au langage has overcome the problems I mentioned. Granted, many of the shots have sharply-etched images that emphasize the thinness of each plane. But other shots have unusual volume. Several factors may contribute to this. Unusual angles sometimes give foreground elements a greater roundness. This happens in the low-angle tracking shots created by the toy-train rig shown above.

In addition, the relatively low resolution of some of the images avoids creating hard contours.The wavering blown-out softness may enhance volume.

Perhaps as well the slight tremors of the handheld camera mimic one of the factors that yield volume for our normal vision: the very slight movements of our head and body. Such shots shift the aspect enough to suggest the thickness of things.

Godard maintains the sense of depth in a tiny ways. For instance, he discovers that the crackling snow on a TV monitor can yield shimmering depth in the manner of Béla Julesz’s random-dot stereograms. Julesz sought to show that 3D vision wasn’t wedded to perspective cues or the identification of recognizable objects–a conclusion that ought to appeal to the painterly side of Godard.

Production stills indicate that Godard shot the film with parallel lenses. Instead of creating convergence by “toeing in” the lenses during filming, he and his crew played with the images in postproduction to control planes and convergence points. What they did exactly, I don’t know, but the results yield, for me at least, some strong volumes and a continual impression of depth that doesn’t wane.

I wish I could analyze the film’s 3D technique more exactly, but I don’t know enough about the craft of stereoscopic cinema or Godard’s creative process. What this film shows, however, is that 3D is a legitimate creative frontier. In the credits, as usual Godard brusquely lists his equipment, from the high-end Canon 5D Mark II (and Canon is proud to be associated with him) to small rigs like GoPro (in 3D) and Lumix. What is clear is that filming in 3D can be pictorially adventurous with cameras costing a few hundred dollars.

Nature, the ultimate metaphor

Now I’ll concentrate on the first few minutes, at the risk of potential spoilers.

The narrative in Adieu au langage is sketchy even by Godardian standards. Normally he gives us some characters in a defined situation (though it takes a while for us to grasp what that situation is), and a series of more or less developed dramatic scenes that advance a sort of plot. In Passion (1982) a movie director recreates famous paintings on film while a factory owner, his wife, and a worker get embroiled in his project. Detective (1985) carries us through a stay of several people at a luxury hotel. Je vous salue Marie (1985) gives us not one but two plots (Adam and Eve, Joseph and Mary). Éloge de l’amour follows a young writer in his exploration of art dealing and commercial filmmaking.

Adieu au langage doesn’t give us a plot even as skimpy as these. Instead, Godard builds his film out of a bold use of ellipsis and a strict patterning of story incidents. The ellipses are exceptionally cryptic. We must, for instance, eventually infer, on slight cues, that a couple has been together for at least four years, and that the man has stabbed the woman. We learn, with almost no emphasis, that both of the women have ties to Africa–hence the footage of street violence and the recurring question of how to understand that continent.

These very vague plot elements are arranged in a rigorous pattern. This patterning will seem very schematic in my retelling. But it’s not obvious when you see the film. Godard wraps his film’s grid in digressions, sumptuous imagery, and, of course, striking 3D effects.

To get a sense of both the firm architecture and the wayward surface, let’s look at the opening. The first fifteen minutes of Adieu au langage introduce in miniature what the rest of the film will be doing.

A montage of citations before the credits is followed by a fuzzy image of a neon sign. Now we get a sort of overture. Frantic video shots of a crowd under attack and running to a fire are followed by a clip from Only Angels Have Wings and a close-up of the dog identified in the credits as Roxy. That’s followed by a black frame dotted with points of white light. That image will become a little clearer later (stylistic suspense again). Then a title superimposes the numeral one in red with the word, “La Nature.”

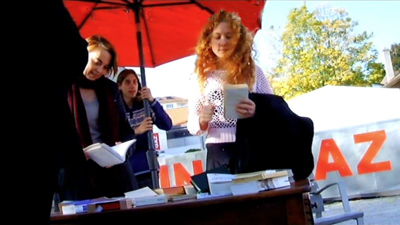

What ensues, after a shot of a ferry approaching a pier, is a fairly disjunctive scene. A booksellers’ table stands across the street from the Usine a Gaz, a cultural center in Nyon, Switzerland. People casually gather there: a redheaded woman (Marie), a young man in a sweater who seems to be the bookseller, a woman on a bicycle (Isabelle), and the older man Davidson (later identified as a professor), here seen from the rear.

The cockeyed low-angle framing might make you think that this is Godard’s Mr. Arkadin, but it suggests footage from a camera or cellphone simply left tipped on some surface behind the table. In that respect it would make manifest the line in Éloge de l’amour: “The image, alone capable of denying nothingness, is also the gaze of nothingness upon us.”

Soon Davidson is sitting in the street commenting on Solzenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago as a “literary investigation.”

A question he asks Isabelle behind him leads to a punning exchange about the thumb (pouce) that we use on our phones, which leads to a question about Tom Thumb (Poucette), a pun on “push” (pousser), and the suggestion that digital icons are like Tom’s trail of pebbles to the giant’s castle. The little skein of associations knots in a remarkable shot of two pairs of hands tickling their mobiles while another person’s hands examine books.

As the men swap phones, a car coasts through the shot in the background.

This scenic fragment, suppressing faces that would help us identify characters, is characteristic of Godard’s approach in the whole film. He isolates gestures and surroundings, letting sound suggest the scenic action; and often the most important narrative action—here, the arrival of the car carrying a gunman—is a minor element in the frame.

So far, we’ve seen one of Godard’s strategies for hiding his story action: ellipsis. Time is skipped over (Davidson behind the table/ in a chair/ then perhaps behind the table), and bits of scenic action are omitted. There is also the opaque framing that impedes character recognition. What about digression? ? We’ve had one example in the Tom Thumb dialogue, but digression can be more overt. Godard can insert shots that have only a tangential narrative connection to the action.

The Godardian digression usually develops in a spreading web of associations that takes us on a detour. Here, one trigger seems to be the mention of Tom Thumb’s Ogre; another is the video display on the phones. These bits lead to a montage about Hitler, who, a woman’s voice reflects, left behind the belief that the state should handle everything. In a polyphony with the woman’s voice reflecting on Hitler, we get Davidson reflecting on how Jacques Ellul foresaw a good deal of the contemporary world. The associational links spread further, to images of the French revolution, crowds hailing Hitler, crowds at the Tour de France, and finally flowers and a voice reiterating a question at the scene’s start: How to produce a concept of Africa?

Now we’re back to the street, with the car pulling up. A chair that may have been Davidson’s is now empty. A man in a suit, the husband, emerges and lights a cigarette, looking off left. A woman, Josette, is in close-up—evidently the target of his look.

Since a black-and-white shot of Josette, head bent, was inserted in the Hitler montage, it’s possible that hers was the voice reciting the argument about the enduring trust in state authority. Perhaps she is reading? In any case, no sooner has a drama of sorts started than we get another digression. Marie reads aloud to us from a book held by the sweater boy. Again, the subject is state power and its inability to acknowledge its violence.

Domestic, not state-sponsored, violence is next on the agenda. A long shot shows the husband stalking up to Josette and berating her in German. The Usine sign is a big help in anchoring the action in the space we’ve seen, and Isabelle’s bike is visible on screen right.

Josette hangs stiffly on his arm, passively resisting and saying, “I don’t care.” He rushes out left. Gunshots are heard, and she jerks in spasmodic response. People rush through the frame. (We’ll never learn exactly what happened offscreen, though later there’s a hint that someone was shot.)

After the car has turned around and left in the way it came, Josette walks stiffly out of the frame. The man in the background who was startled by the husband’s abuse walks to the empty chair and pauses for a time to stare at it.

Cut to leaves floating on water, with hands washing and a man’s voice off saying: “I am at your command.”

So far, so Godardian. The narrative gist is that a woman has fled her husband, refused to return to him, and been approached by a different man who offers to join her. But the flow of images and sounds has made that gist very obscure, obliging us to absorb some fairly ravishing images and to listen to words, noises, and music as they form jagged, interruptive patterns.

And now something very unusual happens. Godard re-plays the events of “1-Nature” in a different location and time of year, using some new characters and some old ones.

A new section, “2” supered on “Metaphor,” appears. Its opening images run parallel to the overture that led up to “1.” After a shot of a swimmer (echoing the previous image of water), we get newsreel footage of combat and fire, and another film extract, this one from Les Enfants Terribles. A shot of Roxy along a river bank is followed by one of a hand opening and closing as a woman’s voice speaks of the “return” of language and a title repeats her insistence that she has made an image.

As at the start of “1,” the ferry comes toward the pier. And now we’re back with Davidson, now sitting along the edge of the water, again reading. His position and the tipped angle suggest a mirror-image of the earlier shot of him near the book table.

A link to the previous scene is provided when Marie and the sweater boy come to Davidson and say they’re going to America. The boy will study philosophy (obligatory quote from Being and Nothingness follows). Their conversation is interrupted by the arrival of the husband again, who shouts and fires his pistol. The shot announcing him is another skewed mirroring: his earlier entrance is inverted–again, as if a mobile phone’s camera had fallen.

The young couple flee and a woman, Ivitch, steps in to talk with Davidson. She shouts at the husband in German, “There is no why here!” ( a line that gets explained later in the film) and tells Davidson to ignore him. This moment offers a variant of the close shot of Josette when the husband had approached.

Ivitch asks Davidson, who evidently has been her professor during the previous term, questions about fighting unemployment by killing workers and about the difference between an idea and a metaphor.

In a new angle, Davidson meditates about images. As if to confirm the professor’s hunch that images murder the present, the husband lunges into the frame and yanks Ivitch out. We now get a shot in which the two cameras diverge: the left eye stays on Davidson, the right one pans over to Ivitch and the husband overlooking the lake. This offers a dense composition akin to that of the book-table shot, with figures piled on one another. The superimposition below is somewhat faithful to what we see, but it can’t convey your temptation to close one eye, then the other, in creating your own shot/reverse-shot editing.

The husband paces around Ivitch, points the pistol, and hollers in German that she’s a dirty whore. She replies as Josette had: “I don’t care.” She walks back to Davidson on the bench, and shortly the husband strides back to the car waiting in the background. Davidson returns to Ivitch’s question about metaphor and then points out two kids playing with dice. These exemplify “the metaphor of reality.” Cut to the kids rolling three dice.

The image echoes Godard’s segment of 3 x 3D, where he puns on “D” as dés, or dice. The kiddies’ shot literalizes the metaphor: trois dés, 3D.

Finally we see Ivitch behind a grille, looking up, then down as we hear the ferry’s horn off. A man’s hand comes in from the left, voice off: “I’m at your command.”

This action repeats the end of the “1” section, but differently: There we saw Gédéon when he inspected Josette’s chair, and heard him say the same words over the leafy water shot. Here both the words and the face of the speaker, Marcus, are offscreen.

Again a woman is threatened by her violent husband and a man emerges to replace him. Again that action is occulted by verbal digressions, dislocated framings, and major characters–here, Marcus–not introduced in a normal fashion. Once more the separate pieces of the scene, straining to cohere, are pulled apart just enough to register as individual instants of beauty, shock, puns, metaphors, or just peculiarity.

Godard’s prospectus for Adieu au langage indicated: “A second film begins. The same as the first.” This describes, laconically, what we’ve seen in the first fifteen minutes. That parallel structure is laid out again with astonishing, yet mostly hidden, rigor in the film as a whole.

Two plus two

Maximal spoilers here.

Over the last thirty years or so, we’ve had plenty of films that replay sections of their stories. Sometimes that dynamic is motivated as time travel, as in Source Code or Edge of Tomorrow—“multiple draft” narratives that let characters, as in Groundhog Day, revisit situations until they master them. Sometimes the repetition has been motivated through varying point of view, so that we see the same action again, but from a different character’s perspective. Examples would be Go, Lucas Delvaux’s Trilogy, and Ned Benson’s recent Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby. Once in a while we get films that present the events as repeated but significantly and mysteriously different. This is what happens in some Hong Sang-soo films, such as The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, as well as in Lee Kwangkuk’s Romance Joe.

In all, this is a minor but important convention of modern screenplays. The replay plot is common enough for screenwriting guru Linda Aronson to consider it separately in her book The 21st Century Screenplay. Trust Godard to take this emerging norm and fracture it.

The opening I’ve just considered invites us to see the film as split into two storylines. Godard has explored duplex construction before, in Éloge de l’amour (with the second part in color video) and Film Socialisme (with its third “movement” appended to two long sections). Yet Adieu au langage offers something different.

Here we have multiples of two: a prologue bookended by an epilogue, the two opening parts that are mirrors of each other, and then two long sections that are uncannily symmetrical. Those sections continue the stories sketched out in the opening section. Each plotline bears the same title as before, but now presented in different graphics (the number and the words are not superimposed, but presented in separate title cards). What’s remarkable is the precise parallels and echoes set up between the pair of tales.

The couples were cast with resemblances in mind, and this affinity is expanded through rather precise doubling. Nearly every scene in the plotline of Josette and Gédéon has its counterpart in the one featuring Ivitch and Marcus. Two nude scenes, two toilet scenes, two bloody-sink scenes, two mirror scenes, two movie-on-TV scenes. There are parallel sequences of driving in the rain, of a woman fleeing into a forest, of Roxy wandering in the woods, of helicopters crashing, of men dying in fountains. As we saw in the early 1/2 segments, the shots’ framings often echo one another.

Godard has laid bare the device in the second story, when Marcus and Ivitch and Marcus talk in front of a mirror.

Marcus: Look in the mirror, Ivitch. There are both of them.

Ivitch: You mean the four of them.

Rather than exact repetitions, we get repetition with variation. One couple takes Roxy in, the other (perhaps) does not. The first couple abandons Roxy on a pier in summer; in the second part, the pier in winter stands empty.

Most remarkably, the parallel scenes of the long section “2/Metaphor” proceed in almost exactly the same order as in “1/Nature”. Evidently Godard shot the bulk of the first story well before he shot the second. It’s as if the first film became the script for the second. In any event, the two long parts mirror one another with unusual precision. This geometrical structure recalls the “grid” organization of Vivre sa vie, but it’s not announced as boldly. Godard refuses to mark the parallel scenes in normal ways–with titles, or musical motifs. The labeling of the sections, 1 and 2 in the intro, 1 and 2 in the longer stretches, are sufficient for this laconic filmmaker.

Just as Godard blurs the shape of individual scenes through digression and opacity, so he hides the tabular structure of the film behind interruptions, landscape shots, and above all the charmed wanderings of Roxy, who more or less takes over the last portion of the second part. In addition, certain images from the second part echo or condense images we’ve seen before. The blood-filled fountain at the end of the second tale echoes both the bloody sink of the first one and the floating-leaf fountain in the prelude, while the clasping hands seem to consummate the gesture begun in the grille shot. These hybrid images can only make the strict double-column scene lineup more difficult to notice.

The fact that the exceptionally exact parallels and orderings of the two parts aren’t remarked upon by critics (I began to sense them a little during my second pass) is a measure of how successfully Godard has camouflaged the film’s anatomy. What shall we call this tactic? Distant counterpoint? Barely discernible rhymes?

Second film, or two films (short and long) times two: We’re free to see the characters as couples running uncannily in synchronization, or as the same couple in two guises, or as two stories in parallel universes. More likely, though, Godard is distressing and disheveling the emerging conventions of replay plotting.

And yet the ending of “the second film, same as the first” isn’t quite the whole story either. Godard has always enjoyed setting up rigid structures and then spoiling them–cutting off the arc of a melody or chopping a shot that could have been breathtaking. So he cracks his elegant 2 + 2 structure by giving us an epilogue and a third couple.

Images recur: crowds on the streets, Roxy snuggling on a sofa, a TV (but this time with two empty chairs). We glimpse a man reading, but mostly we see one hand painting with water colors while another is writing in a journal. Godard’s familiar dichotomy between image and word is here tied to the harmony of an unseen, but clearly heard, man and woman making art in tandem. The male voice seems to be Godard’s; I can’t say whether the female voice belongs to his partner Anne-Marie Miéville, but the woman seems to understand Roxy best. She can even access his thoughts. (“He’s dreaming of the Marquesa Islands.”) Yet this couple has another parallel, shown a little earlier: Percy and Mary Shelley, a poet and a novelist, the latter seen finishing Frankenstein in the forest. This is at least one farewell to language, but it also implies that creativity binds a couple together.

Roxy Miéville, as he’s called in the credits, haunts the film. He checks out streams, train platforms, and tree roots. He is never seen in the same shot with the main characters; his link to them is tenuous. His ramblings suggest freedom, sensory alertness, and a trust in immediate experience that perhaps the people can’t attain. The final images after the credits show Roxy wandering off in the distance and then bounding eagerly back to someone who stands, of course, offscreen.

Godard: The youngest filmmaker at work today.

Many thanks to Robert Sweeney and Richard Lorber of Kino Lorber, a bold company that still believes in art films. It will be releasing Goodbye to Language on 29 October (not September as I erroneously stated in an earlier version of the entry.) Later the film will appear on Blu-Ray 3D. Thanks also to Marc Silberman for help with German translation and to Ben Brewster for advice on stage wings.

For an interesting memoir of the filming of Adieu au langage, see Zoé Bruneau’s En Attendant Godard (Paris, 2014). The photo of the camera train is drawn from p. 93 of her book.

An excellent evocation of the fizz of word and image in Adieu au langage is offered by James Quandt in Artforum (also in the September print edition). Some other stimulating appreciations of the film are Scott Foundas in Variety, Daniel Kasman for MUBI, and Blake Williams in Cinema Scope. A useful description of the film is by Jean-Luc Lacuve on the site of the Ciné-club de Caen.

Too bad the GoPro Fetch, a harnessed camera for dogs, wasn’t available for Roxy to use.

To get a sense of how complex Late Godard is at the level of narrative comprehension, see Kristin’s essay “Godard’s Unknown Country: Sauve qui peut (la vie),” in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. I analyze strategies of storytelling in Godard’s 1960s films in Chapter 13 of Narration in the Fiction Film. She wrote about Film Socialisme on the blog here. For a discussion of Godard’s very fussy compositions, try this entry. I consider multiple-draft narratives more generally in the essay

“Film Futures” in Poetics of Cinema.

P.S. 30 Sept: Since Adieu au langage screened at TIFF, VIFF, and elsewhere, a great many critical responses have accumulated. Thanks to the assiduous passion of David Hudson, you can track them all at Fandor. My initial posting should have mentioned two more enlightening discussions of the film: Kent Jones’s Cannes thoughts and the heroic display of Godardiana assembled by Craig Keller at Cinemasparagus.

P.P.S. 15 October: The beat goes on. Ted Fendt’s astonishing list of “Works Cited” in the film, which I added to the body of the above entry, deserves another link here. And the ever-expandig Mubi deserves our thanks for making it available.

P.P.P.S. 29 October: And more, of course. Background on the production process from Fabrice Aragno for Filmmaker; David Ehrlich’s sensitive discussion on The Dissolve; and a story on NPR, with interviews with Héloïse Godet, Vincent Maraval, and (gulp) me. Thanks to Pat Dowell for asking me to participate.

P.P.P.P.S. 2 November: If you haven’t had enough, I posted another entry on the film.

P.P.S. 13 November 2014: Geoffrey O’Brien’s enthusiastic appreciation of the film not only illuminates it but conveys the excitement of seeing it.

Where movies live and breathe

Thanks to web tsarina Meg Hamel, I’ve just posted a new essay (you also see it on the left column). It’s a historical and personal discussion of film archives. It could also be titled, “How I Spent Nearly 40 Summer Vacations.”

It originally appeared in Nicola Mazzanti’s book, 75000 Films. More on that book and related topics soon! After I get done arm-wrestling Adieu au langage, the latest work of the world’s youngest 83-year-old filmmaker.

Zip, zero, Zeitgeist

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014).

DB here:

The silly season always seems to catch me off guard. This time I got the word in a New York Times feature, “The Moviegoers.”

Here two writers, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, conduct an email conversation about recent films. You may have thought that the Times already has a large stable of movie reviewers, headlined by Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott. But mainstream movies are very accessible (as opposed to, say, serial music or Baroque architecture), so nearly everybody has something to say. And because nobody knows what counts as expertise in movie reviewing, why not bring on two of the commentariat? Once you become a public intellectual, what you say about anything is interesting.

Granted, both participants in the dialogue, Frank Bruni and Ross Douthat, have been movie reviewers. Mr. Bruni wrote for the Detroit Free Press, and Mr. Douthat currently covers film for the National Review. Through some process yet unexplained, these movie reviewers became second-string social and political pundits for the Times. That would seem a step up, so why put them back in the reviewing game?

The rationale is supplied in the series introduction, which talks of the plan to discuss “movies, pop culture, television, and other real-world distractions.” The Times style guardian might want to pause on the last phrase: Are these phenomena distractions in the real world (as in “real-world opportunities”)? Or are they distractions from the real world? I think the writer means the latter, which translates into this: Politics is the important stuff, mass art is a lightweight diversion. And we all need diversion, especially a newspaper aiming to attract readers under fifty.

So we have two Op-Ed columnists taking a break from serious matters in order to shoot the breeze about summer releases. In “Two Thumbs Up…Yer Arse.” Charlie Pierce, our fouler-mouthed Mencken, has exposed some curious assumptions about poverty displayed in the Moviegoers’ first round of chitchat. What interests me here is another aspect of the column, which showcases one standard move that many reviewers make.

The problem for serious people like Mr. Douthat and Mr. Bruni is this. If movies are “real-world distractions,” why spend any time talking about them? More specifically, why should political pundits talk about them? The obvious answer: Somehow these products of popular culture open a window into what’s really going on. Mr. Douthat:

In this sense I do think moviemakers are tapping into the American psyche, but I also think they’re replicating a flaw of the American political debate. I’m not sure we’ll get very far by painting the rich as morally hopeless people who must be subverted, vanquished, overtaken.

And when Mr. Bruni asks, “Tell me about the trend that made you happy, and (speaking of political allegories) whether you like ‘Apes’ as much as everyone else,” Mr. Douthat replies:

There was something poignant about watching “Apes” against the backdrop of the mess in the Middle East and of the war in Israel and Gaza, because it’s a disturbingly good allegory of reciprocal mistrust, asking the right questions about how peace ever reigns when combatants can’t bring themselves to forgive error, to take the first step, to turn from the past and focus on the future, to start afresh. It’s a disturbingly good allegory about corrupt leaders, too: how they whip up fervor in the service of their own ambition; how we rise and fall based on the clarity and wisdom with which we choose them.

You may want to reply that if this is what the Times wants, you will undertake to supply them with 3000 words of it every day at reasonable rates. But put aside the banalities about politics. I’m interested in the suggestion that movies can bear traces of the national psyche, or reflect national debates we’re having right now, or provide inadvertent “allegories” of contemporary history.

These ideas enjoy an astonishing popularity. They are staples of movie journalism. The trouble is that they don’t hold up.

Reflections on reflectionism

That mass entertainment somehow reflects its society is, I believe, the One Big Idea that every intellectual has about popular culture. The notion shapes the Sunday Times think piece about how the movies of the last few months capture the current Zeitgeist (or one a while back). It informs the belief that we can define periods in American popular art by presidential eras–Leave It to Beaver as cozy Eisenhower suburban fantasy, Forrest Gump as an expression of Clinton-era post-Cold-War isolationism. Reflectionism may be the last refuge of journalists writing to deadline, but it’s also found in the industry’s talk about itself. “Oscar Best Pic Contenders Reflect America’s Anxieties,” Variety announced last winter.

The threat of circularity. Behind this Big Idea is an assumption that cinema, being a “popular art,” tends to embody some state of mind common to the millions of people living in a society. The very idea of a massive mind-meld like this seems implausible. America’s anxieties and our national psyche? The anxieties of the 1% are not yours and mine, and I doubt that even you and I share a psyche.

The argument easily becomes circular. All popular films reflect society’s attitudes. How do we know what the attitudes are? Just look at the films! We need independent and pretty broadly based evidence to show that the attitudes exist, are very widespread, and have been incorporated in films. And it won’t do to simply point to the same attitudes surfacing in TV, pop songs, mass-market fiction as well, because that just postpones the problem of correlating the attitudes with groups of living and breathing people.

Critics seem to assume that if a film is successful at the box office, it must reflect the audience’s inner life. Yet the sheer fact of a movie’s popularity doesn’t prove that these attitudes are out there. Just because Spider-Man (2002) was a huge success doesn’t mean that it offers us access to America’s national mood or hidden anxieties. People spend time with a piece of mass art for many reasons: to kill an idle hour, to meet with friends, to find out what all the fuss is about. After the encounter, consumers often dislike the art work to some degree, or they remain indifferent to it. Since people must buy the movie ticket before they experience the movie, there can’t be a simple correlation between mass sales and mass mood. You and lots of others may be suckered into going to a film you dislike, but just by going you’ve already been counted as among those who support it. Doubtless many people enjoyed Spider-Man. But it’s very difficult to say how many.

And did all of the patrons who enjoyed it do so for the same reasons? That remains to be shown, and it’s hard. We know that a movie may appeal to several audiences at once, packaging a range of appeals. In fact, it’s a strategy of the film industry to produce movies that contain fuzzy messages, contrary attitudes, and something for nearly everybody. Must we find reflections of cultural needs in every aspect of a movie that might appeal to somebody?

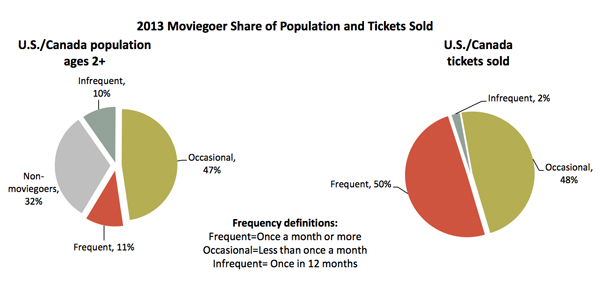

Movies are narrowcasting. The film audience is a skewed sampling of the population. According to industry statistics, about one-third of Americans over the age of two never go to the movies, and another ten percent go once a year.

Another 40% go “occasionally”–less than once a month. It turns out that the heavy moviegoers, those going once a month or more, are currently just 11% of the population. Take Dawn of Planet of the Apes. Assuming an average ticket price of $8 and no repeat viewings, at most about 25.5 million Americans and Canadians have seen the movie. That’s about 7% of the countries’ total population. We would need to tell a pretty full story about how the mental life of 350 or so million people gets into movies seen by a thin, self-selected slice of the population.

Moviegoers are atypical of the population in other respects. Since the beginning, Hollywood cinema has catered to the middle class. Moviegoers have been younger, better educated, and better-off economically than non-moviegoers.

The real mass medium of our time is network television (as radio was before). On one night, a single episode of The Big Bang Theory can attract 19 million viewers. A film that had that viewership across an opening weekend would take in over $150 million. That is $50 million more than the latest Transformers movie garnered at its debut. If Messrs. Douthat and Bruni want to take the national temperature, they should watch TV–ideally, the ads on the Super Bowl (shown to 112 million viewers).

Actually, you can argue that television really is a more reliable barometer of mass tastes, not just because of its prevalence but because TV viewing depends on recidivism. People may not know they’ll like a movie before they attend, but they tune in to shows that have proven to satisfy them. Still and all, mass taste is not the national psyche.

The long road from the White House. A primary prop for reflectionists is politics. Talk about an American film of the 1950s and sooner or later someone will invoke the reign of blandness that was (purportedly) the Eisenhower administration. But why do we assume that the population’s mind set switches its course whenever a new President is elected? Many voters stubbornly adhere to the same values election after election; others vote in order to throw out a rascal and aren’t at all satisfied with the newcomer.

There couldn’t be a direct tie between elections and moviegoers’ attitudes. About thirty percent of today’s audience consists of people too young to vote. The most reliable voter turnout is among the over-forty-five set, which until recently constituted only about twenty percent of moviegoers. Of course, maybe movies reflect the attitudes of non-voters, or people who are indifferent to politics. But then why identify periods of political history with periods of movie history?

Reflectionists have always been reluctant to offer a concrete causal account of how widely-held attitudes or anxieties within an audience could find their way into art works. What precise story could we tell to explain how changing the occupant of the White House can affect popular culture? How exactly does a party platform or a candidate’s charisma or the new administration’s policies seep into Hollywood movies for the multitudes?

Movies’ crystal ball. If there ever were a dominant mood at large in the land, it would be very difficult for that mood to find its way into a current movie. There’s often a lag of several years before a script gets to the screen. Many of the films released in 1997, though read as responding to current crises, were bought as projects in 1993 and 1994. Dawn of Planet of the Apes was begun in 2011, written through 2011-2012, and began shooting in April of 2013–all before the current standoff between Israel and Hamas.

Maybe the moviemakers are somehow in touch with political forces before they crystallize? One critic has proposed that films can have this prophetic power. Puzzled that no Obama-era movies had emerged by 2012, J. Hoberman suggests that the most “Obama-ite” ones came out before Obama was elected:

The longing for Obama (or an Obama) can be found in two prescient 2008 movies—WALL-E (the world saved by an endearing little dingbot, community organizer for an extinct community) and Milk (portrait of another creative community organizer—not to mention a precedent-shattering politician who, it’s very often reiterated, presented himself as a Messenger of Hope).

This is nearly a miracle. Somehow these filmmakers sensed that Americans (well, 53% of the people voting) were yearning to be led by a community organizer. But how specifically could the filmmakers have arrived at that prescience? In fact, they would have had to be long-range prophets. Milk began as a 1992 project, and the final version of the script was prepared in 2007. The Pixar adepts started talking about WALL-E in 1994 and began drafting scripts in 2002. Why don’t we ask filmmakers to predict our next president right now?

Pick and choose. Of all the films of the summer, Bruni and Douthat settle on a few. Of all the hundreds of 2008 films, two presage Obama. This selectivity is typical of the reflectionist approach, which typically ignores the range of incompatible material on offer.

If 1940s film noir reflects some angst in the American psyche, how to explain the audience’s embrace of sunny MGM musicals and lightweight comedies in the same years? The year 1956 saw the release of The Ten Commandments, Around the World in 80 Days, Giant, The King and I, Guys and Dolls, Picnic, War and Peace, Moby Dick, The Searchers, and The Lieutenant Wore Skirts. Pick one, find some thematic concerns there that resonate with social life of the time, and you have a case for any state you wish to ascribe to the collective psyche. But take any other movie, or indeed the industry’s entire output, and you have a problem. One alternative is for us to find that the films share common themes, but these are likely to be of an insipid generality. Or we could float the rather uncompelling claim that several hundred films reflect hundreds of different, and contradictory, facets of the audience’s inner life.

Consider the source. Of course filmmakers sometimes deliberately include political comment. But then the film is “reflecting” the purposes of its particular makers, not the mass public. The filmmaker may claim to be tapping the Zeitgeist, but it’s really the Zeitgeist as she or he understands it. It’s not the public expressing itself spontaneously and unselfconsiously through the movie.

Movies use a lot of collaborators, and they may have varying agendas. The most powerful players are inevitably going to shape the initial project in specific, often personal ways. The preoccupations of the screenwriter, the producer, the director, and the stars necessarily transform the given idea. And these workers, living hermetic lives in Beverly Hills and jetting off to Majorca, are far from typical. How can the fears and yearnings of the masses be adequately “reflected” once these elites have finished with the product? Maybe some violence in American films gets there not because the crowd secretly wants it but because Hollywood creators compete in pushing the envelope. Once more we need a story about how widespread opinions get incarnated in the work of an unrepresentative group.

In sum, reflectionist criticism throws out loose and intuitive connections between film and society without offering concrete explanations that can be argued explicitly. It relies on spurious and far-fetched correlations between films and social or political events. It neglects damaging counterexamples. It assumes that popular culture is the audience talking to itself, without interference or distortion from the makers and the social institutions they inhabit. And the causal forces invoked–a spirit of the time, a national mood, collective anxieties–may exist only as abstractions that the commentator, pressed to fill column inches, invokes in the manner of calling spirits from the deep.

Primate see, primate do

This isn’t to say that society has no impact on films. Of course it does. But we understand that process best by taking film as film.

Film critics serve us best when they explore how a film uses the medium to yield its effects. Critics can enlighten us about how filmmakers work with their givens (subjects, themes, genres, artistic traditions, star personas) and generate an experience shot through with meanings, feelings, and ideas. We should recognize that a large part of any movie is the result of will and skill, not the passive reflection of vague social turmoil. There will be some unintended effects too, of course, but we can try to understand those as coming from specific conditions of production practices, traditions, and creative options.

One first step, for example, would be to consider Dawn of the Planet of the Apes as following the plot pattern of the revisionist Western.(Spoilers follow.) The humans, like settlers in the west, need resources held by the apes, who live in self-sufficient harmony with nature. They wish others no harm. A well-meaning emissary from the humans, Malcolm, leads a team into ape territory to tap an energy source. Thanks to Malcolm’s promises of peaceful coexistence, humans and apes become friendly. But other members of Malcolm’s team don’t trust the apes and provoke violence. There is also the brooding ape Koba, who wants revenge for his mistreatment in experiments. The peace treaty is broken by both sides.

Koba, Caesar’s friend and rival, escalates the war with the humans when he discovers the cache of weapons. While Caesar tries to keep Koba from fomenting rebellion, Malcolm must try to restrain the humans’ leader, Dreyfuss. This is a familiar duality: the unruly tribal brave hot for vengeance who must be disciplined by the wise chief, and the sensible lieutenant who tries to restrain his rapacious superior.

The science-fiction premise has been shaped to fit the familiar pattern of liberal Westerns, in which blame can be placed on weak, cowardly, vengeful, or power-hungry individuals who block well-meaning leaders from finding peace. The classic equivocation of Hollywood film (there’s always an element that says, “Yes, but then there’s…”) is well summed up by the ambivalent to-camera glare of Caesar that begins and ends the movie: Angry? Sorrowful? Defiant? Implacable? Your mileage may vary.

The political themes are sculpted in another way, through family parallels. Caesar has a wife, Cornelia, and a son, Blue Eyes. Malcolm has a wife, Ellie, and a son, Alexander. The prospect of peaceful coexistence between human and ape is encapsulated in the two families’ growing fondness for each other. The parallels are sharpened by contrasts. Alexander comes to accept the apes, while his more rebellious adolescent counterpart Blue Eyes temporarily aligns himself with the false father Koba—only to prove himself loyal to Caesar at the climax.

By contrast, Dreyfus and Koba are lone males, without women or offspring. Granted, we are allowed some sympathy for both: Koba has been mistreated by humans, and Dreyfus has lost his family in the collapse of civilization. Still, Caesar is morally superior to both because he has lived in each world harmoniously. Before the final battle, the wounded Caesar gets to recall his first human family, typified by his father figure, on video.

Onto the settlers vs. Indians plot, then, is grafted what film scholars have called a “family adventure” pattern, one that became prominent in the 1980s and 1990s with E. T.: The Extraterrestrial, Jurassic Park and other films seeking “four-quadrant” success. The result is more made-in-Hollywood archetype than grassroots allegory.

My sketch is Film Studies 101 and needs plenty of nuancing. To go further we should consider how this movie, or any movie, puts flesh on its plot bones. How does the film handle point-of-view and exposition? How does it generate sympathy or antipathy? How does it create character conflicts both external and internal? Does it accord with the sharply contoured plot architecture characteristic of US studio filmmaking (and maybe popular literature too)? If I were trying to do a finer-grained analysis of Dawn, I’d try to understand how the Western and family-adventure templates intertwine with these factors and gain force as the film unfolds.

The point would be not to suggest that these plot patterns reflect the attitudes or anxieties of the audience, let alone a national psyche. Rather, the patterns are chosen by the filmmakers because they have proven emotionally appealing to at least some viewers (and apparently in cultures outside the US). And they can be fashioned to accord with contemporary norms of moviemaking. Instead of passive reflection, we have active creation.

It isn’t all controlled by the filmmakers. Like all actions, filmmaking can have unintended consequences. If some members of the audience respond in the way the filmmakers wanted, so far, so good. If the results are grasped in ways that the makers didn’t expect or prefer, that comes with the territory too. Mass-market filmmakers take inherited forms and tweak them in new ways. The audience, in its turn, appropriates what it’s given, sometimes in predictable ways, sometimes in unpredictable ones. No national psyche is needed for this process to keep rolling.

Instead of reflection, better to think of refraction, the bending and reconfiguring of social themes under the pressure of filmmaking traditions. We understand mass-market films better when we see them as, sometimes opportunistically, grabbing material from the wider culture (whether that material reflects mass sentiment or not) and transforming it through narrative and stylistic conventions. That transformation, or rather transmutation, is central to the artistry of popular entertainment.

Movies are worth studying for themselves, not just as channels for Op-Ed memes. Critics who are sensitive to the art, craft, history, and business of cinema will be able to enlighten us about all aspects of a film, including its political ones.

Jeff Smith’s new book, Film Criticism, The Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds examines how critics of the 1950s found allegories of resistance to HUAC in movies made at the time. It’s a good reminder that this sort of reflectionist criticism goes back pretty far.

In tune with Jeff’s argument, in an earlier entry I argued that reflectionist readings of popular cinema intensified during the 1940s. But our best critics pushed back. Parker Tyler proposed that movies don’t so much reflect social myths as they invent their own, and he suggested that the process follows the zany logic of dreams. Otis Ferguson, James Agee, and Manny Farber mostly avoided Zeitgeist explanations and talked about films’ implications in relationship to art, craft, and other media and artforms. I survey their work in a series of recent entries: on Ferguson, on Agee, on Farber (here and here), on Tyler, and on their originality, their cultural context, and their legacy.

The pie chart come from the MPAA report on 2013 moviegoing, p. 11.

For a wide-ranging and skeptical examination of one aspect of this topic, there’s Alan Hunt’s article, “Anxiety and social explanation: Some anxieties about anxiety,” Journal of Social History 32, 3 (Spring 1999), 509-528.

Peter Krämer developed the concept of the family adventure film in contemporary Hollywood. See his “Would You Take Your Child to See This Film? The Cultural and Social Work of the Family Adventure Movie,” in Steve Neale, ed. Contemporary Hollywood Cinema (Routlege, 1998), 294-311.

If there’s an allegory in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, perhaps it’s a Bolshevik one. Josef Stalin was known as Koba, which would make Caesar a Lenin figure and Rocket a stand-in for Trotsky. (I doubt that the conservative Mr. Douthat would welcome this reading.) If the reference is intentional, it provides a good example of how a Hollywood film simply seizes cultural flotsam willy-nilly, perhaps to give intellectuals something to ponder. As Christopher Nolan explains of his Batman trilogy: “We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks.”

Parts of today’s sermonette are pulled from an essay published in Poetics of Cinema in 2008. That essay also charts areas of control that filmmakers and audiences enjoy. Another entry on this site dealt with these questions in relation to The Dark Knight and, again, the good, grey Times.

Daumier: Types Parisiens (1840-1843): “Ah, I can see my street, there’s my house, there’s my garden and my wife, I can see Laurent – Oh, I have seen too much.”

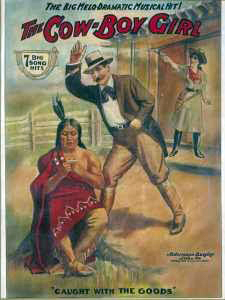

The AMBERSONS Poster Mystery: The clincher

DB here:

Bingo! Crowdsourcing pays off. Alert blogger Ivan Paio found the original poster that’s tucked into the Magnificent Ambersons frame! It confirms that Welles used not a film poster but one advertising a stage show…that could have played the Bijou in 1912.

If you’re not familiar with our quest, you can go here and here and here. Be sure to visit Ivan’s site for details, and give him a big hand.