Archive for 2014

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Strands from the 1950s and 1960s

Faraon (1966).

Kristin here:

David has already posted an early report on his first full day at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. It conveys something of the overwhelming abundance of offerings at this year’s festival. Writing another entry during the festival itself proved impossible, given our packed schedules, but now we have time to catch our breath and reflect on what we were able to see.

As with the 2013 festival, I decided that the only way to navigate the many simultaneous screenings was to pick out some major threads and stick with them. I chose the retrospective of Polish widescreen films of the 1960s, that of Indian classics from the 1950s, and the third season of early Japanese talkies. Miraculously, none of these conflicted with each other, the Polish films being on mainly in the mornings, the Japanese ones directly after the lunch break, and the Indian films starting late in the afternoon.

Again, it was possible to fit in a few films from the other programs on offer, including a series of Germaine Dulac’s films, restorations of East of Eden and Rebel without a Cause, a selection of Riccardo Freda’s work, Italian contributions lifted from various anthology films of the 1950s and 1960s, a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Österreichisches Filmmuseum, and many Chaplin shorts (the festival was preceded by a brief conference on Chaplin).

The annual Cento Anni Fa program, showing films from 100 years ago, has changed, in part to accommodate the fact that the transition to feature films was well underway. The series programer, Mariann Lewinsky, has also branched out. Having discovered many unknown or little-known early silents during her annual quests, she has included other brief thematic programs, such as fashion in early films. In addition, there was a lengthier selection of early films dealing with war, given that we are now in the centenary of World War I.

A Journey from Pole to Pole

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965).

To me the biggest revelation of the festival was the program of Polish anamorphic widescreen films. Representing most of the major Polish directors working in widescreen in the 1960s, these were shown in 35mm, mostly in original release prints from the period, on the big screen of the Cinema Arlecchino theatre. Despite occasional wear in the prints, they looked great.

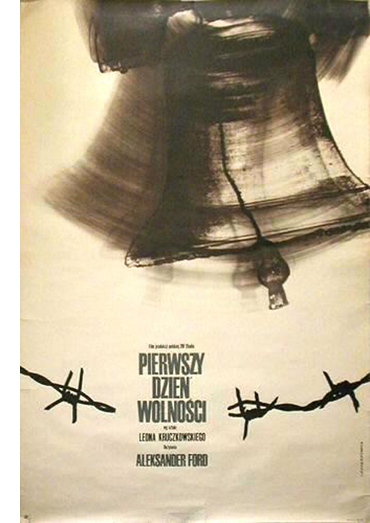

The series kicked off with Aleksander Ford’s little-known The First Day of Freedom (Perwszy dzień wolności, 1964). Like many of the films in the program, it dealt with World War II. Polish soldiers, escaped from a POW camp, enter a nearly deserted German town. They disagree on whether to help protect the civilians they encounter or participate in the general rape and pillage in the wake of the Nazi retreat. It’s a grim and realistic look at a topic seldom tackled in films about the war.

Also on the program was Andrej Munk’s Passenger (Paseżerka, 1963), left unfinished when the director was killed in a car accident. His colleagues eventually decided to assemble the film without additional footage, drawing upon still photos for some scenes and an effective voiceover filling in the action. The effort works well, and the result is a powerful examination of a Nazi death camp. The story does not concentrate on Jews but on political prisoners, implicitly communists and other rebels. The result is the sort of disguised political comment on Poland’s contemporary situation that is common in these films.

Early on, a middle-aged woman aboard a ship tells her companion about her life in as an official in the camp–a story that is contradicted when the actual scenes of her activities at the camp play out. The woman singles out a female prisoner, Marta, and rationalizes her irrational mixture of rewards and punishments as efforts to save her from the other prisoners’ fates. With its depictions of cat-and-mouse games between prisoners and captors and its references to mysterious sadistic rituals played out by the guards, the film is a powerful meditation on the camps, worthy, as Peter von Bagh’s program notes say, to sit alongside Resnais’s documentary, Night and Fog.

Among the unexpected delights of the series was Lenin in Poland (Lenin w Polsce, 1966) by Sergei Yutkevich (or, as he is credited here, Jutkevič). Yutkevich began as a member of the Soviet Montage movement, contributing a little-known, late feature, Golden Mountains (1932). Working in Poland, he managed the formidable task of humanizing Lenin in unorthodox ways. Yutkevich concentrates on the leader’s Polish exile on the eve of World War I. Framed by Lenin’s brief imprisonment on charges of espionage, the film proceeds through flashbacks to his recent activities. As portrayed by Maksim Strauch, whose resemblance to the revolutionary leader gave him a long career in numerous films, Lenin is humorous, kind, thoughtful, and a likeable protagonist. Yutkevich includes touches from the Montage movement, with some passages of quick cutting and frequent heroic framings of the protagonist.

With my interest in ancient Egypt, I was particularly curious about Faraon (Pharaoh, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1966). The director tackles the unusual and obscure topic of the end of the 20th Dynasty, which led to the end of the golden age of the New Kingdom and the instability of the Third Intermediate Period. The film’s drama comes from the real-life conflict between the impoverished, weakened monarch and the wealthy, powerful priests of Amun in Thebes. I’m not sure how well an audience not familiar with this era would follow the plot, even simplified as it is. There are some remarkable crowd scenes, as at the top of this entry, when Herhor, the chief of the priests, rallies the crowd against the pharaoh. Still, I did not find the story engaging. Presumably it was a covert commentary on politics in Poland at the time.

The best-known of Polish directors, Andrzej Wajda, was represented by two films. One was the earliest film shown in the series, Samson, from 1961. It concerns a young Jewish man who is lured to escape from the Warsaw Ghetto and spends most of the film dodging the police by moving from one temporary haven to another. Wajda creates a compelling depiction of the ghetto early on, and I wished he had stayed in that environment longer.

My favorite film of the festival was Wajda’s little-known Ashes (Popioły [not to be confused with Ashes and Diamonds], 1965), an epic tale of the Napoleonic wars and Poland’s unwise participation in them on the side of the French. The protagonist, Rafal Olbromski, is a naive young nobleman from a rural area, a Candide-like figure whom we follow as he leaves his estate to go to war and moves from locale to locale, manipulated by more sophisticated characters. The result is a dizzying succession of battle scenes, largely without any context being established, punctuated by visits to the estates of those who are backing the Polish participation in Napoleon’s conquests. Wajda seemed to have had nearly limitless funds for the film, and the battle scenes are monumental.

Far less obscure is Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (Rękopis znaleziony a Saragossie, 1965), a cult item among film buffs and reputedly one of Luis Buñuel’s favorite films. It’s a complex, surreal tale of a wandering soldier of the 18th Century who passes the gibbets of two executed men in a bleak Spanish landscape and enters a mysterious inn. There he encounters a large bound manuscript that leads him into a world of shifting fantasy and tales within tales within tales. Has’s was certainly one of the most humorous and entertaining films in the series.

The latest film in the program, Adventure with a Song (Przygoda z piosenka, Stanisław Bareja, 1969), was radically different from the others and provided a look at popular Polish cinema of the 1960s. Bareja was a successful director of comedies and musicals. This one follows a young singer who wins a local singing contest with the improbably named “The Donkey Had Two Troughs,” and decides to head for a professional career in Paris. The filmmakers’ attempts to replicate the Mod styles and garish colors of the 1960s in the West yield an incongruous and awkward but fascinating film .

The one disadvantage of seeing these vintage distribution prints (mostly with English subtitles) was that some were abridged versions, occasionally radically so. Samson, The First Days of Freedom, Adventure with a Song, and, inevitably Passenger were shown complete. Judging by imdb’s timings, however, others were missing significant amounts footage: Ashes (shown at 169′, originally 234′), The Saragossa Manuscript (155′ vs. 175′), Pharaoh (149′ vs. 180′).

Recently there seems to be a revival of interest in Polish classic films. Martin Scorsese has curated a large program that is currently touring the US with digital copies of restored films. (For links to numerous articles on the series and the restorations, see its Facebook page.) I hope that some enterprising company will issue the complete versions of these Polish classics in their proper widescreen ratios. Ashes is a particularly good candidate for such treatment. Having sat through it once at nearly three hours, I would happily watch it at closer to four.

Worthy of restoration

There’s a growing interest in recent Indian films, at least in the USA. Our biggest local multiplex nearly always devotes  one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

One reason is because many of these classics still await restoration. While most programs shown in Bologna consist of newly restored prints, this series was titled “The Golden 50s: India’s Endangered Classics.” Each of the features was accompanied by an episode of “Indian News Review,” a newsreel that for years was shown in film programs across India. Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder of the Film Heritage Foundation, curated the series and introduced each film, emphasizing that even the eight classics selected for the program are in danger if not properly restored soon.

The need was evident from the prints. Some were old distribution prints, but three of the films could only be shown on Blu-ray. Even under these conditions, however, the range and quality of Indian cinema of the 1950s was apparent.

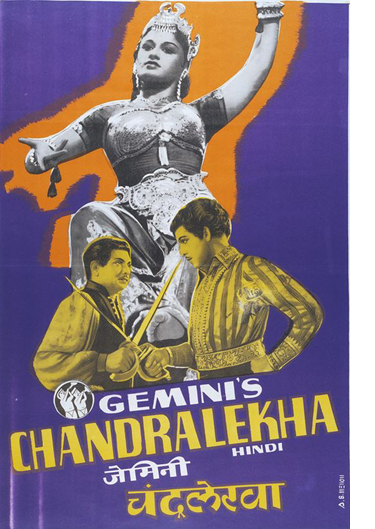

The earliest film in the series, Chandralekha (S. S. Vasan), was made a little before that decade, in 1948. Its presence stems from its crucial importance in Indian film history. It was the first big, successful Indian musical of the post-colonial era and set the pattern for many of the country’s subsequent films. The story has a fairy-tale setting, with a good and an evil brother fighting over the throne of their father’s kingdom and also for the hand of the beautiful Chandralekha. The rambling plot includes lots of songs and dance numbers, leading up to the climactic, legendary Drum Dance (below right), with dozens of dancers atop rows of enormous drums. It lives up to expectations. (For more on Chandralekha, see fellow Ritrovato fan Antii Alanen’s epic blog post.)

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

One of the great Indian directors, Ritwik Ghatak, has become somewhat familiar in the West, thanks in part to the British Film Institute’s issuing two of his masterpieces on DVD: A River Called Titas and The Cloud-Capped Star. The series at Bologna included Ghatak’s first feature, Ajantrik (1957). It is set among the poverty-stricken Oraons, an isolated population in Central India, and follows a man who is devoted to his dilapidated taxi, which he manages to hold together well enough to supply him a marginal living. He has come to think of the car as a human companion. (Accordingly, the title means, roughly, “not mechanical,” although for western distribution it was given the unenticing title Pathetic Fallacy.) Though Ajantrik is not a major film on the level of the others in the program, it was good to have the rare opportunity to see Ghatak’s first film.

The star of the series was undoubtedly an equally respected director, Guru Dutt. Two of his films, in both of which he also starred, were shown. One of his finest films, Pyaasa (The Thirsty One, 1957), was perhaps the best film of the program. Dutt is considered to have integrated the conventional song episodes of Indian cinema into his films more skillfully and in more original ways than other directors.

Dutt plays a great but unappreciated poet whose work is ignored by the intelligentsia of his own class. He wanders in despair among the poor and outcast, for whom he has great sympathy. In one haunting scene, he walks through a brothel district and sings of his despair for humanity (below). Early in the film he meets a prostitute who appreciates his poetry and falls in love with him. Only after the poet’s apparent death does his work become widely loved among the the common people, but his reputation is exploited by his hypocritical family and publisher.

Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959), was also shown. Again Dutt plays an unappreciated artist. A film director divorces his wife and becomes the target of gossip when he casts a beautiful young actress in his next movie. His personal misery affects his ability to direct, and after a slow slide into alcoholism, he loses his job. The plot allows Dutt to express self-pity more obviously than in Pyaasa, and the comic scenes with his ex-wife’s family strike an odd tone in such a grim story. Kaagaz Ke Phool was not a success, and Dutt gave up filmmaking altogether, dying of an overdose of sleeping pills five years later. As Dungparapur pointed out, he was one of several important Indian filmmakers who died rather young, which makes the rescue of these classics all the more essential.

Pyaasa (1957).

Gas food lodging: The best job in the world has its downside

Honoré Daumier, Exposition des Beaux-Arts, 1869.

DB here:

Over the last couple of years, I’ve been worried about those critics who must suffer the indignities of film festivals. I became aware of the hazards when I saw this exchange on Indiewire about James Gray’s The Immigrant:

Critic: Do you see this as your most emotional work?

James Gray: I don’t know, I mean I hope so. I know this sounds phony but I don’t start out on a project going, “I’m going to make an emotional work,” you know what I mean? You try to tell the story directly and honestly and with passion…

(A server interrupts to make sure we’re OK and leaves.)

Gray: I love France, I love the French, I’m ready to go home. Three days it took me to get my underwear back from the laundry. Also the worst concierge service in all of human history. I had tickets for all these guests of mine, and they said “Oh, we’ll slip it under your door,” and like seven hours later they lose the…anyway, I’m sorry.

Critic: No, no. Getting a glass of water at this hotel takes half an hour.

Gray: Yeah, it’s like scaling K2.

Mr. Gray, they say, is an amusing guy, so perhaps his complaints were wry jokes. I hope not. These slights and discomforts deserve to be recorded. They might seem minor to someone not professionally employed to fly to Cannes, but they’re typical of the hazards critics submit to for our sake. Curious, I looked into the recent adventures of some high-profile writers.

In all, critics bear their indignities with remarkable aplomb. They are unfailingly generous with praise when things are going well. Take the communiqués of Meredith Brody. Her encounters with famous people (luckily for us, she knows everyone) mingle with tales of fashion and delectable dining. As one who misses old Hollywood, I’m pleased that the festival scene has its Hedda Hopper. Here’s a bulletin from Telluride:

With the kind permission of Steve Ujlaki, dean of the Loyola Marymount University School of Film and Television, I was able to join his table for dinner at Rustico at 6, down a lovely plate of veal with mushrooms, and still make Serge Bromberg’s 7:15 “Retour du Flamme.” . . . It took me a while to find Alice Waters’ rented house, tucked away at the top of a steep street, but inside I find great wine, charcuterie, cheese, bread, chocolate, and refugees from the festival’s starriest party, to which I hadn’t been invited. . . .

I told Alexander Payne I was sad that they hadn’t scheduled an additional screening of the 1965 Italia film “I Knew Her Well” that he’d introduced night before last. . . . And maybe he was pulling my leg, but he said something about it being scheduled at some cinematheque in his home state of Nebraska, where he lives part-time. . . . Tom Luddy arrived in a dazzling Russian constructivist cashmere sweater, which his wife, stylist Monique Montgomery, had found at the Alameda Flea Market. He was thrilled that Dave Eggers and Vendela Vida had so enjoyed their first visit to Telluride that they’d become lifers.

And from Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato:

Walking back from “La Grande Illusion” last night, I run into Haden Guest (of the Harvard Film Archive) and Rani Singh of the Getty Institute, on the way back to their hotel. Days ago I told Haden I wanted to introduce him to Steve Ujlaki, Dean of the Loyola Marymount University School of Film and Television; it turns out they met accidentally on their own, in a fascinating-sounding wine bar, although they didn’t get around to actual introductions. I realized it must be Haden Steve and Jackie were talking about when they said that he was elegantly dressed, “in a pork pie hat and linen jacket.” I confirm this by showing him pictures of them from the amazing dinner we’ve just shared.

I frustrate both Haden and Rani by describing the meal and not being able to tell them the name of the restaurant. That’s something that annoyed the hell out of me when I was regularly writing about restaurants and people would tell me they’d just been to a place I would love and then be unable to tell me its name or address. I can show them a picture of the façade of the place, but it’s hard to read the sign. . . . A last lunch at Bertino: prosciutto e melone, straw and hay with sausage sauce, tagliatelle with ragu. Only a glance at sparkling wine (dare not) and a heavily-laden dessert cart (better not).

The churlish will object that the films screened get little discussion in these flavorsome pieces, but that misses the point. The function of most festival reviewers is to function as a DEW system, or a first filter. They must signal those buzzworthy films that if we’re lucky, we’ll see a few months or years hence. Their task is to predict the winners. (Indeed, their coverage helps create the winners.) Given that the films will be over-discussed in the months to come, why not share with us the more ephemeral joys of the festival atmosphere–the parties, the food and drink, the networking, the celebrity bons mots?

When it comes to evoking la dolce vita of the festival circuit, no one surpasses Mark Adams of Screen Daily/ Screen International. Consider his 2012 description of the annual Arabian Nights party at the Emirates Palace Hotel at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival.

The party aims to replicate – as only a five-star hotel can do – the desert experience, and is set up with food-stands a-plenty as well as singing, dancing, a Western-style DJ (very popular), shisha pipes – for those who partake – and even chill-out seats out on the sand with the possibility of a close encounter with a camel.

In fact this party has developed into a must-go-to event for festival regulars, with an elegant and laid-back vibe that is a perfect counterbalance to the excitement of the opening night bash and the champagne excesses of the Möet & Chandon event.

Champagne excesses? Tell us more, especially the classy parts.

The nice thing about the Moët & Chandon bash is that it is delivered with a certain class. The champagne was chilled and tasty, the asparagus risotto delicious and the delicate desserts delightful. Plus there were fire-eaters, a dancer sprayed silver and a woman dancing in an oversized birdcage….

But while the Moët party was certainly a classy affair – and with a strict invite list it keeps things modest but classy – it all rather pales when you head back into the Emirates Palace hotel and its cavernous golden corridors, gleaming hallways, splendid domed foyer and sheer sense of confident opulence….

Gold and marble are the key aspects to the hotel. Much has been written about the gold ingot vending machine in the foyer, but love it or loathe it there is no denying the sheer visual impact of the building, which was designed by architect John Elliott, and which opened in 2005.

Forget the 1.3km of white sandy beach, the private marina and the two helipads…the Emirates Palace hotel is all about scale. It is 1km from wing to wing (100 hectares total area); there are 102 elevators (I’ve only used two) and 1002 chandeliers, and some 5kg of pure edible gold is used per year for decoration on desserts.

At a period when people are losing their jobs, not getting jobs, losing their savings, finding themselves unable to save, and generally suffering from a depressed economy and a failing social-services system, it’s entirely appropriate that Adams spare a thought for those less fortunate than his hosts.

Sadly that self same edible gold on some very nice strawberriess at a Swedish reception was the nearest I’ve come to getting my hands on the real thing. . .

He’s quite aware that not every venue can splash out this way. The Transylvania Film Festival gamely makes do.

Even the faded and empty Continental Hotel on the edge of the square was being used for a costume exhibition that seemed to fit perfectly into the crumbling main entrance hall of the hotel, with its musty smell and peeling, once-grand ceiling.

And Adams reminds us:

Maybe it’s a sign of the times, but even movies are reflecting the stark fact that expensive hotels are beyond the reach of many, and camping or caravanning are other options. Camping was very much the thing in Cannes opener Moonrise Kingdom. . . .

Still, even if you stay in fine digs, there are those hazards. Without hesitation Adams throws a spotlight on the dangers of being a festival-going critic–plagued by officious doormen, long queues, and chattering cinephiles. Even the weather sometimes fails to cooperate.

After stints at the Venice and Toronto film festivals let me tell you, my capacity — let alone enthusiasm — for queuing is pretty much depleted. Yes, getting there nice and early does guarantee you a seat but standing in line is an intrinsically wearying pursuit as you stave off boredom by waving to friends, checking e-mails and becoming more and more annoyed as sly folk cajole or charm their way into the line ahead of you. . . .

At Venice this year, most of the early press screenings (which sometimes mixed in members of the public) were held at the cavernous Darsena cinema. With 1,300 seats available there’s always a good chance you’ll get in, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t a variety of ruses tried by some to force their way into the queue at an earlier point. Some try the old ‘friend holding a place’ routine; others adopt the ‘phone glued to ear and not really aware there was a queue’ policy, while some are just plain rude.

Mind you, it was so hot in Venice that the outdoor queue was rather wearisome, though at least the security folk didn’t snaffle water and liquids of any kind as they did in Cannes this year. Oddly there were three queues set up for the Darsena depending on your badge — from priority daily press through to periodicals — and all were let in at exactly the same time. . . .

Toronto favours long, winding queues that weave back and forth, like being in a bank or an airport baggage drop-off. In the case of screenings at the Bell Lightbox this also involves going up escalators, marshalled by grinning volunteers and festival folk with annoying headsets. But while frustrating they are quite well organised — until you are left outside a film that is late starting due to a digital problem, and have to put up with film folk around you pontificating on every film they have seen.

Fortunately, you can get away from the grind occasionally. Unlike Brody, who sandwiches her gustatory adventures between screenings, Adams favors a vacation. Even during R & R, however, he’s on the job, passing along his musings on cinema.

Time for a well-earned holiday with friends and family down in the bakingly hot Tarn region of southern France. Blessedly it is an area not favoured by hordes of British tourists but — rather sadly — it lacks a plethora of multiplexes to catch up on the latest film fare.

There was not even a local film festival to overlap with my trip, unlike a holiday in Umbria a few years ago, where a tiny and picturesque hilltop town was staging a Mike Leigh retrospective. And no, much as I love Mike, I didn’t hang around to catch his appearance.

While floundering in the pool, tanning in the 37 degree heat, sampling the delightful variety of Gallic wines and sweating on a baking-hot tennis court were all fine distractions, let’s face it, you can’t beat a good movie.

I wrote the foregoing a year ago, but I decided not to post it. I thought that the trend I’d spotted had faded. Film critics seemed to have given up their scintillating travelogues for the humdrum task of discussing movies. But a recent report from Anne Thompson made me decide to revive the old piece. A couple of days ago, Thompson took off for Karlovy Vary.

I flew from LA to Paris en route to the 49th Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (KVIFF) on a 500-seat double-decker Air France A380 that is the largest passenger aircraft in the world. Lufthansa and Emirates Airlines also fly them. It’s the smoothest, quietest flight ride I’ve ever had, you barely noticed the plane taking off.

I walked, “Snowpiercer” style, through the economy steerage, up the curved staircase at the tail and back through business and first class, which features ten full sleepers. The three-year-old jumbo jet had video footage of three live cameras mounted on the nose, belly and tail.

Cool.

So far, so good. But where are the eats?

Later that night I ran into Gibson and his long-time publicist Alan Nierob in the VIP basement lounge of the Grand Hotel Pupp, as the opening night party raged through many rooms above, with lavish spreads with everything from roast beef, aspic and deviled eggs to tongue-melting fresh sword steaks grilled on demand. He [Mel] showed me his latest movie-star tattoo.

On cue, Meredith Brody posts a culinary comment.

ps: two things: I know it would be kinda a busman’s holiday, but did you see any movies on the plane? AND tongue-melting sushi?!

As if in reply, Thompson’s second day report features more tastiness and adds a picture and a comparison of film to–what else?–food.

I interviewed achievement-award-winner Mel Gibson on video (we’ll post soon) before the official festival dinner at the Grand restaurant. I nibbled at a paté of duck liver and fois gras with cherries and beetroot as I chatted with the city Mayor (who runs a film club) and the Czech Minister of Culture, who is a rare Roman Catholic in a country of post-Communist atheists….

I interviewed achievement-award-winner Mel Gibson on video (we’ll post soon) before the official festival dinner at the Grand restaurant. I nibbled at a paté of duck liver and fois gras with cherries and beetroot as I chatted with the city Mayor (who runs a film club) and the Czech Minister of Culture, who is a rare Roman Catholic in a country of post-Communist atheists….

I’ll report anon on what I do see–of the 200-some films on display are a tempting smorgasbord of the best of the international festivals.

I think I speak for other readers: Festival critics, we know you face moments of despair. But make the sacrifice. Soldier on. Tip us to strong sweepstakes entries. (Thompson on Calvary: “This will make many critics’ ten-best lists.”) And don’t spare us lifestyle details.

Full disclosure: Kristin and I have praised Lillooet Fox‘s waffles at VIFF.

12 hours, Ritrovato time

DB here:

Reporting on the magnificent Cinema Ritrovato festival at Bologna has become a tradition with us, but it’s become harder to find time during the event to write an entry. The program has swollen to 600 titles over eight days, and attendance has shot up as well; the figure we heard was over 2000 souls. The organizers–Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée–have responded to requests for more repetition of titles by slotting shows in the evening, some starting as late as 9:45. (You can scan the daily program here.) There are as well panel discussions, meetings with authors, and some unique events, such as carbon-arc outdoor shows, the traditional screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, and Peter Kubelka’s massive and mysterious Monument Film. Add in time to browse the vast book and DVD sales tables, and the need to socialize with old friends.

In all, Ritrovato is becoming the Cannes of classic cinema: diverse, turbulent, and overwhelming. How best to give you a sense of the tidal-wave energy of the event? I’ve decided to take off one morning and write up just one day, Monday 29 June. I don’t know when Kristin and I will find time to write another entry, for reasons you will discover.

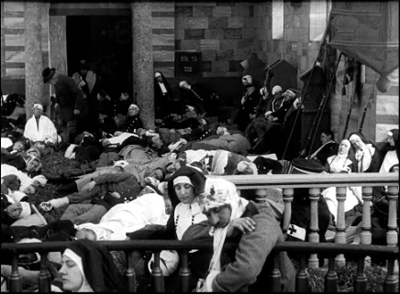

9:00 AM: Ned Med Vaabnene! (Lay Down Your Arms!, 1914) was a big Danish production, based on a popular anti-war novel by the German Bertha von Suttner. It’s a remnant of the days when the rich went to war along with the common folk. (Sounds quaint in today’s America, where the elite have other priorities.) The Nordisk studio specialized in “nobility films,” melodramas that show the upper class brought low by circumstances; Dreyer’s The President (1919) is another example. The film, directed by Holger-Madsen, shows a family devastated by war and its aftermath. It’s shot in tableau style, with the restrained acting and sumptuous, light-filled sets characteristic of Nordisk. The combat scenes are remarkably forceful, but the most harrowing scene, for me, is the shot showing a battlefront hospital, with exhausted nuns and wounded men strewn around the shot–a tangle of limbs and heads.

Premiered soon after the Great War broke out, Lay Down Your Arms! anticipates Nordisk’s wartime policy. Denmark was a neutral country, and the Danish industry depended on both the German and the American markets. As a result, most of the films studiously avoided taking sides. After the war, with the revival of the German industry and the circulation of American films in Europe, Nordisk lost its powerful position in the international market.

The entire film is available for viewing online at the Danish Film Institute site.

Programmer Mariann Lewinsky, in charge of the “100 Years Ago” thread, wisely included other pacifist films from the mid-teens. One of the high points was the evening screening, on the Piazza Maggiore, of the fine Belgian film Maudite soit la guerre (1914), in the hand-colored version I discussed some years back. Not by accident, I suspect, Lay Down Your Arms! featured several Lewinsky dogs.

10:30 AM: Werner Hochbaum was an unknown name to me, but after seeing Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow, 1933), I realized that was my loss. This story of a cafe violinist released from prison is a sort of anthology of 1920s International Style devices: canted angles, rapid montages, City Symphony passages, flamboyant camera movements, multiple-image superimpositions, and huge close-ups of faces, hands, and objects. The work on sound is no less ambitious, with voice-overs, sound motifs (a carousel, a canary’s call-and-response to a chiming doorbell), offscreen dialogue, and harsh auditory montages of traffic and city life. Everything from Impressionist subjective-focus point-of-view to Expressionist shadow work comes into play.

The plot is gripping throughout. At first we don’t know why the violinist was imprisoned, and we learn about the case first from his gossiping neighbors (excellent run of whispers during fast-cut close-ups of housewives), then from his own flashbacks, which build up to a revelation of the murder he committed. Threaded with all this is another uncertainty: Has his wife begun a love affair while he was in jail? Giving us only glimpses of her life as a cafe waitress, Hochbaum leads us to suspect that he will come home to more misery–and perhaps another temptation to murder.

Along with all this were arresting side scenes of cafe life, like a fat woman ordering up a gigolo to dance with her, reminiscent of Georg Grosz and the New Objectivity’s cynical portrait of daily desperation. It’s a lot to pack into 73 minutes, but Morgen beginnt das Leben succeeds smoothly and made me want more. Alex Horwath‘s introduction confirmed that this is a director we should know better. We can hope that a DVD edition is coming soon.

Noon: A packed house for the panel of three American studio archivists: Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox, Grover Crisp of Sony, and Ned Price of Warners. Too many ideas to summarize here, but one that emerged: Digital tools are great for restoration, not so reliable for preservation.

Ned (left) emphasized that now scanners are very sensitive to the oldest negatives, with their shrinkage and warpage. But Ned pointed out that today’s monitors don’t often render the full color scale needed to respect film’s tonal range, so that weak monitors mean that we are “working blind” and may “bake in” flaws that will be evident when display devices improve. Likewise, low bit-depths (often only 10-bit) in outputting to film for preservation can cause problems later. Grain reduction is another big problem. Grover (center) added: “When you do anything to grain, you’re denaturing the film.”

On the restoration front, Schawn showed clips from the 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth, first from a beautiful photochemical restoration of twelve years ago, then from a recent digital one. To my eye, the warm skin tones of the 35mm image were more attractive than the almost porcelain surfaces of the digital version, but the latter was sharper and contained a healthy amount of grain. Grover screened A/B comparisons of the main titles of Only Angels Have Wings and Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa (Sandra ), both of which showed how handily digital restoration creates a rock-stable image, without the jitter and weave unavoidable with a strip of film.

All the panelists agreed that digital restorations are rapidly improving; ones finished only a few years ago could now be done better. A major problem coming up is that younger restoration workers know the digital tools better than the look and feel of photochemical, particularly the surface of older films. Grover recalled that one eager techie added flicker to a Capra silent because he thought that was how old movies looked.

1:15 PM: Hurried lunch with Schawn. Main topic: The Grand Budapest Hotel, but also the vagaries of the DVD and Blu-Ray market.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

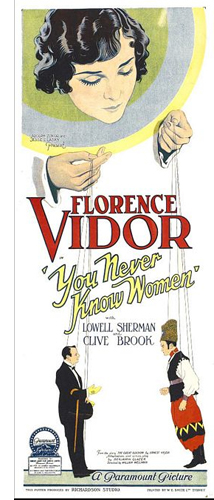

You Never Know Women (1926) is an exercise in good old classical storytelling. The plot presents Vera (Florence Vidor), star of a troupe of Russian entertainers, momentarily entranced by a no-good millionaire who wants to seduce her. The magician of the troupe, Norodin (Clive Brook) loves her, but she’s unaware of her feelings for him until the Lothario’s true nature is exposed. El Brendel adds spice as a clown devoted to his pet duck.

Variety‘s review was ecstatic, claiming that “Wellman at the megaphone lifts himself into the ranks of select directors with by his handling of this story, for his direction is never obvious or old-fashioned.” I’ll say. Filled with running gags, seesawing conflicts, and motifs (Ivan’s skill at knife-throwing, the expletive, “Ridiculous!”), You Never Know Women has a headlong pace. With nearly a thousand shots in 70 minutes, it relies on glances, gestures, and reactions to channel the dramatic flow. It needs only three expository titles, letting its 100 or so dialogue titles pinpoint key emotional transitions. In anticipating the sound cinema that was just around the corner, You Never Know Women resembles the more famous Beggars of Life (1928, given pride of place at Ritrovato), which as I recall uses dialogue titles exclusively.

The Man I Love (1929) tells the familiar story of a prizefighter who, as he rises in the game, leaves his loyal woman behind. As an early sound film, it relies on multiple-camera shooting for extended dialogue scenes, but Wellman enlivens the staging with unusual angles, including a view of a quarrel seen through a window in a dressing-room door. The Man I Love boasts the sort of ambitious, somewhat bumpy tracking shots we sometimes find in early talkies. One swaggering camera movement takes us from the locker room into an arena, down the aisle, past the ring, and to Dum Dum’s anxious wife in the crowd, a sketchy prefiguration of the celebrated Steadicam movement in Raging Bull. The fight scenes, not requiring sync sound, are shot with brio, while the dialogue scenes are extremely well-miked, allowing for fairly fast line readings and varied volume and emphasis in the voices.

Gina Teraroli and David Phelps, along with other colleagues, have assembled a wide-ranging dossier on Wellman’s work that serves as a fine complement to the Ritrovato thread.

5-something PM: One of the things in the first edition of our Film History: An Introduction that made me proud was the inclusion of sections on Indian cinema, a subject usually ignored in textbook surveys. I remember in the late 1980s and early 1990s watching the 1950s-1960s classics of Hindi filmmaking with a sense of discovery: How could we not have known this invigorating tradition? It was therefore with a sense of homecoming that I visited Raj Kapoor’s Awara (“The Vagabond,” 1951), in a pretty sepia-tinted print.

The young ne’er-do-well Raj (no last name, and this is important) is on trial for attacking a judge in his home. A female lawyer, Rita, takes up his defense and urges the judge, on the witness stand, to tell why he expelled his wife from his home many years ago. The wife had been kidnapped by the gangster Jagga, and the judge assumed that the child she was now expecting was Jagga’s. Before the courtroom, Rita recounts up the story of how young Raj, actually the judge’s legitimate son, took up a life of crime. To add spice, Rita is the judge’s ward and Raj’s lover.

No coincidence, no story, they say, and Awara offers plenty of timely misunderstandings and improbably neat encounters. No matter. We’re told that TV narrative, by stretching its tale over several hours, can introduce novelistic breadth, but so can Indian classics of the 1950s. This one takes us across twenty-four years and as many ups and downs as a mini-series might offer. Not to mention Kapoor’s vigorous visual style, with huge sets, vivacious fantasy sequences, and traces of 1940s Hollywood hysteria (chiaroscuro, fluid track-ins to overwrought faces, even thunder and lightning in the distance). Here Raj, about to stab the judge, shatters the childhood picture of Rita; her simple gaze checks his moment of revenge.

Then there are the songs, lusciously sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Mukesh. Of course the sprightly “Awara Hoon” is the official classic and Kapoor’s signature tune, but this time around my favorite was the duet, “I wish the moon…,” with Rita asking the moon to look away and Raj asking it to turn to him. With its glamorized social realism, its tale of a good boy gone wrong, unjustly punished, and eventually redeemed, and its primal themes of mothers, fathers, and sons, Awara is a milestone in the world’s popular cinema…. and just one of several Indian classics in this year’s Ritrovato.

That was one day. Now I’m off to…what? Polish films in widescreen? The Riccardo Freda retrospective? The rare Ojo Okichi? Or maybe the restored Oklahoma!? In any case, this afternoon an incontro on Nicola Mazzanti‘s book 75000 films, and tonight Guru Dutt’s glorious Pyaasa.

I tell you, it’s hard to keep up, running on Ritrovato time.

Nargis and Raj Kapoor sing to the moon in Awara.

Prague summer

The Ascension of Christ, panel from the Vyšši Brod Altarpiece, ca. 1350. Convent of St. Agnes, Prague.

DB here:

Kristin and I are in Prague for about a week, in connection with two lectures I’m giving Wednesday and Thursday.

In the meantime, we’ve met with friends. After we arrived we had a lively dinner with Radomir Kokes, specialist in Czech silent film. Last night we met with Petra Dominková and Vaclav Kofron, translators of the Czech editions of Film Art and Film History, and Michal Bregant, head of the National Film Archive (and who also contributed to the translation of Film History). During that enjoyable evening we learned, among other things,that film lovers of Michal’s generation took the train to Hungary to see American films that didn’t make their way into their country.

Later, meeting with Radomir and our principal host Lucie Česálková , we learned of their robust, long-lived journal Iluminace, which publishes film research in both Czech and English. The most recent issue is devoted to studies of film festivals.

So far we’ve spent the rest of our time visiting museums. Prague is bursting with rich collections of European art from all eras. Today (Tuesday) we went to one of the major venues, the Convent of St. Agnes, which houses a vast array of Bohemian medieval and early Renaissance painting and sculpture.

There were plenty of images to give us pleasure. One of the most spectacular set of items was a series of fourteenth-century altar panels representing the life of Jesus. Each one gave what seemed to me a fresh interpretation of the major episodes–annunciation, nativity, etc.–but especially striking was the one devoted to the Ascension. After being resurrected, Jesus is lifted to heaven; but contrary to what we usually see, the action is represented “offscreen.” All we see are Jesus’ feet, as above. A nice touch Kristin noticed: He left his footprints in the earth.

I’m drawn to such peculiar treatments of conventional material. There were some other instances in other Prague galleries. Take this piercing image of the mockery of Jesus, in an unidentified Netherlandish painting from the first half of the sixteenth century. The torturers are blowing a cowhorn at Christ, banging a pot, pressing a stool against his head, thrusting a rod into his mouth, and spraying him with a flit gun.

Most remarkably, at the bottom of the composition one man fills a basin with what seems to be shit, while another man dips a cloth in it, as if preparing to apply it to Christ’s face. The suggestion is reinforced by the wizened man on the far right holding his nose.

Such visceral images remind you that holy pictures can be pretty ornery. They also remind you of Jan Švankmajer, that great Czech animator. So far, there’s no museum dedicated to him, but following Petra’s suggestion we did visit the Karel Zeman Museum, just off the Charles Bridge. It offers enjoyable attractions tracing Zeman’s career, with emphasis on Journey to the Beginning of Time (1955) and The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958). Kristin hopes to write at greater length about the museum and Zeman later this summer.

Tomorrow: Off to the world-renowned archive to watch Czech silent films. Who knows what we’ll find?

Thanks to Lucie Česálková and all her colleagues for making our visit possible. Thanks also to Michal Bregant for a correction in the original posting of this entry.

Kristin and I wrote about Švankmajer’s remarkable Dimensions of Dialogue (1982) in the latest edition of Film Art. At the Zeman Museum we discovered a beautiful 2013 book on the filmmaker, available here.

DB at the porthole of Nemo’s Nautilus in the Zeman Museum.