Harry Potter and the Twelve-Year Boyhood

Sunday | March 15, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here–

Note: As far as I’m concerned, Boyhood and the “Harry Potter” films have been out long enough that there is no need for spoiler alerts. It would certainly help in understanding this entry if the reader had some knowledge of the Potterverse.

Apparently audiences who saw Boyhood in its premiere screening at Sundance in January, 2014, went in not knowing that the film had been shot at intervals across over twelve years. Once the reviews appeared, it became known that Richard Linklater had done so, recording the actors, most notably Mason, the boy at the center of the film, actually growing older over the course of nearly three hours. The result was an outpouring of enthusiasm from critics and art-film afficionados alike. Less so, perhaps, from more mainstream viewers who went to see Boyhood once the Oscar buzz heated up. (On Rotten Tomatoes, it is rated 98% favorable by critics and 83% by fans.) From its July release up to the recent Oscars ceremony, it was considered one of the front-runners.

The film’s Oscar campaign took a rather puzzling turn toward the end. The film, which was considered unique in its intimate portrayal of one boy growing up in an unstable family situation, was suddenly “Everyone’s Story,” as if it was so universal that we all could see ourselves in it. The double-page spread from the February 20 Hollywood Reporter (which shows photos from each year of shooting) is too large to reproduce here, but here’s the upper section of the right-hand page:

Virtually nothing in Boyhood‘s story reminded me of anything in my life from six to 18, though, yes, I did graduate from high school and go off to college. Maybe men who as children faced their parents’ divorces, physical abuse, frequent moves to new homes, and so on, would relate to the film and enjoy it more than I did. Or maybe less. I don’t think that seeing this as a universal portrayal of the human condition is very realistic, though that was an idea touted by many critics as well.

I was entertained until the last hour or so, when I realized that Mason was going to remaining fairly passive and sullen to the end. His sister Sam and mother Olivia seemed to be more interesting characters, since they had goals, held strong opinions (right or wrong), made mistakes, accomplished things, and so on.

As an actor, Ellar Coltrane spends much of his time listening to what other actors say to him. His reactions are limited in range and usually involve a fairly neutral expression. In fact, I began to think that his performance is the perfect illustration of Kuleshov’s most famous, though lost, experiment: the one where supposedly the same footage of actor Ivan Mosjoukine looking offscreen was cut together with shots of things like bread, a dead woman, a child playing–things that would logically invoke widely varying emotions. Audiences supposedly praised Mozhoukin’s performance, saying he expressed hunger, sorrow, and happiness admirably. Accounts of what was shown in the shots Mosjoukine was “looking at” vary, and it’s possible the experiment was planned but never made. Whatever was the case, however, the principle seems plausible. What we find in a shot, including a shot of a face, depends on what shots precede and follow it.

I think something of the sort happened in Boyhood. Some expert professional actors, plus Lorelei Linklater as Sam, enacted scenes with Coltrane. Spectators may have imagined how a child would react to the events of the scene and read those appropriate emotions in his frequently impassive face. Otherwise it seems odd that people watching a fairly good art film offering a close, realistic study of a family over a period of twelve years, would consider Boyhood such a moving and historically momentous film.

Putting aside the “Everyone’s Story” appeal, Linklater’s film offers the unique case of a feature film shot across the actual twelve years covered by its story, allowing the actors, most dramatically the young ones, to age before our eyes. That’s impressive in itself, with the producer/director/writer Linklater managing to sustain the momentum of the financing and the actors’ cooperation across the full twelve years. I don’t wish to take anything away from that accomplishment, just to put it in perspective a little.

Wait, did I miss something?

As David has pointed out, films that are innovative, even experimental in some ways often compensate by drawing more heavily upon conventions from other areas. Although the jumps from year to year are somewhat disorienting, Linklater helps us out. He draws upon the old device of having the haircuts of the characters differ each time, even emphasizing this way of marking the passage of time by showing Mason getting an unwanted buzz-cut onscreen. He also characterizes Mason in fairly standard shorthand ways. At the opening he seemingly contemplates death by staring at a dead bird that he is burying. His characterization as slightly rebellious is pretty conventional: looking at semi-clad models in a catalog, allowing himself to be goaded into spray-painting graffiti, flirting with a waitress when he should be clearing tables while working at a local restaurant. Apart from the innovative device of the actor growing across a single film, he’s not a particularly original character.

I think, however, that Linklater does something much more interesting with Boyhood, and it has to do with the narrative structure rather than the aging of the actors. The film tells a deliberately sketchy story. Each one-year segment is obviously part of the characters’ lives, but there is little attempt to bridge the gap between them to create a conventional narrative flow. There are no dialogue hooks to create smooth transitions, no overt continuing goals, just Mason’s implicit desire to make sense of life and Olivia’s to find a happy path forward for her family.

Most obviously, events that would ordinarily be explained or motivated are simply ignored. The cuts from one segment to another are sometimes jarring, sometimes subtle enough that we don’t immediately realize that we’re jumped forward another year. As reviewer Kurt Brokaw points out, there are “no turning calendar pages, no inter-titles signaling the passage of time.”

What happens to Olivia’s third husband? (I’m assuming here that Mason Sr. was her first husband.) We see him before the marriage at a party, and he seems a decent enough sort. In a later segment he is married to Olivia. We see little of him, apart from one evening when his sits on the porch drinking beer and berating Mason for coming home late. Will he turn into another drunken abuser, like the second husband? Instead, he just disappears. Possibly in real life the actor playing him dropped out, in which case it would have been easy enough to mention his death or departure–at least something that would motivate his being gone. We don’t, however, get such an explanation.

Similarly, we are concerned when Olivia flees the home of the second, truly abusive husband, taking Sam and Mason but leaving their two step-siblings behind. Sam is upset and begs to take them along, but Olivia is concerned only to escape with her own children. Do the two kids left behind bear the brunt of their father’s wrath? Do they continue to be abused by him or do they somehow break free? These are important questions, especially after the extended and tension-filled scene in which the drunken man threatens Olivia and all four children. In a conventional narrative they would most likely be answered in some fashion.

Another plot point that I wondered about was the sudden introduction of religion into the narrative when Mason Sr., who has shown no signs of religious inclinations, remarries into a profoundly Christian family. Does Mason Sr. become a believer himself, or does he just avoid strife by attending church with her and her parents?

These and other questions occurred to me and were left unanswered. This is clearly not sloppy storytelling but a systematic strategy. Linklater forces us at each leap forward to struggle a bit to figure out where in these characters’ lives we are now–where they’re living, who is still part of their story and who has departed.

Indeed, I’ve never seen a film that compresses time in such a way as vividly to suggest how many people come and go in our lives, some to reappear, some not. I recently was contacted by a first cousin once removed whom I lost track of when my family moved from the Midwest in 1963. Retired, he was sitting in on a film class that assigned Film Art and decided to find out if one of the authors might be his cousin. Turned out he was living in Milwaukee and I in Madison for decades without knowing it. These things happen, and they do seem as abrupt and surprising as in Linklater’s film. That I can identify with.

I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a narrative film made within or at least on the fringes of the American production system with such frequent gaps and where so many links in the chain of cause and effects are missing. That, in my opinion, is the true innovation of Boyhood, but it’s not something the publicists can sell to the public and the Academy voters.

Right before your eyes

When I heard about the most famous aspect of Boyhood, I immediately thought, “I’ve seen that happen in the ‘Harry Potter’ films.” I was far from the first to think that. An early–perhaps the first–link between the Boy and the Boy Who Lived came as part of the publicity campaign for the film. From July 4 to 10, 2014, the IFC Center in New York ran all eight Potter films in a row as part of a series “honoring the release of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood.” IFC, of course, financed the film and released it in the US on July 11, 2014. Brilliant! as Harry would say.

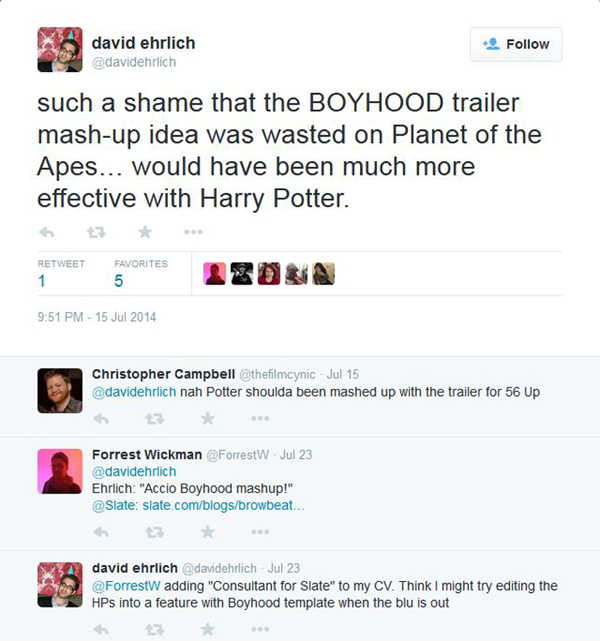

The professional and amateur fans on the internet then took over. On July 15 David Ehrlich (a freelance critic and among other things, Time Out NY‘s associate film editor) suggested a Boyhood/Potter mashup.

You cannot suggest such a mashup on the internet and not have someone take up the challenge. On July 23, Chris Wade posted Potterhood on Slate‘s culture blog, Browbeat, linked in the second comment above. (“Acciao” is a charm for summoning something.) Hence Ehrlich’s last comment in the thread above. A second mashup, also entitled Potterhood, appeared on IGN on February 6, 2015. Hard on its heels was the Honest Trailer – Boyhood, by Screen Junkies, posted on YouTube on February 10, which makes passing reference to Harry Potter. A sequence of five consecutive titles and shots:

The “Harry Potter” series (or, strictly speaking, serial) is only the most recent and well-known example. There have been other “growing-up” series and even a growing-up-and-growing-old series, which Christopher Campbell refers to in the first comment on Ehrlich’s tweet.

Justin Chang pointed out one precedent: “If the ‘Before’ movies are essentially Linklater’s riff on Rohmer, each one an endearingly loquacious two-hander played out against an idyllic Old World setting, then ‘Boyhood’ is unmistakably his tribute to Truffaut, who directed perhaps the greatest movie ever made about restless youth, ‘The 400 Blows.’ Similarly, the French master’s extended collaboration with actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel feels like an early template for what Linklater and Coltrane have pulled off here.”

There are wheels within wheels here. The Doinel series was mentioned to Daniel Radcliffe during an interview, and he responded, “The only one I’ve seen is The 400 Blows. Funny enough, I was asked to see that by Alfonso Cuarón, when he directed the third Harry Potter film. As a reference for Harry and his angst.”

Truffaut’s Doinel series went for a full twenty years, though not with yearly installments: The 400 Blows (1959), Antoine and Colette (1962, a short included in the anthology film Love at Twenty), Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed & Board (1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Unlike the “Harry Potter” series, these films were not planned ahead of time as a group. Truffaut would occasionally pop them in between his other films. They came out after some of his best films–Stolen Kisses after The Bride Wore Black, Bed & Board after The Wild Child, and Love on the Run after The Green Room. At the time we thought of them as Truffaut taking a break after a more difficult project. None of them lived up to the original, but we certainly did watch Jean-Pierre Léaud grow up.

Other critics have mentioned what has come to be called the “Up” series, which began as a television program, Seven Up! (1964) directed by Paul Almond. It consisted of interviews with 14 seven-year-olds. Michael Apted has continued the series with another film every seven years beginning with 7 Plus Seven (1970) and continuing, with the most recent being 56 Up (2012). One participant dropped out permanently, three skipped some episodes, but 56 Up interviewed 13 of the original 14, a remarkable achievement in showing the aging processes across 48 years and still going. Some people have found watching the series a profound experience. Roger Ebert wrote two four-star reviews of it, one in 1998 and another in January, 2013, a few months before his death. He called it “an inspired, even noble, use of the film medium.” But this series is documentary and perhaps not entirely a fair comparison. It is worth noting, though, that Jonathan Sehring, whose IFC had previously produced Waking Life, said that when Linklater pitched Boyhood to him, “The only thing I could draw as a parallel was Seven Up!”

I also wonder if back in the 1930s and 1940s some viewers found it moving as well as amusing to watch Mickey Rooney grow up in the Andy Hardy series, from A Family Affair (1937) to Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1946), plus a revival, Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958), for a total of twenty films. This series was not intended as such at the beginning, but once the popularity of the character was apparent, MGM’s B unit cranked out two or three films a year and clearly planned to keep going indefinitely. These films had self-contained stories, but the subject matter was age-appropriate as Rooney, who was 17 at the time the first film was released, grew older.

Again, all this is not to denigrate Linklater’s film. It’s just a case of this blog seeking again to point out that almost nothing comes out of the blue with no historical precedents or conventions informing it. Certainly none of these series tried the sort of broken chain of causality that Linklater devised.

The Potter connection

Of all the series mentioned above, “Harry Potter” is most pertinent to Boyhood. Their production periods overlapped considerably, and their directors faced similar major challenges. This despite the disparity in their finances. “Harry Potter” had a huge budget supplied by Warner Bros., ranging from the lowest at $100 million for Chamber of Secrets to the highest at $250 million for Half-Blood Prince. (These are the budgets as publicly acknowledged, taken from Box-Office Mojo, which has no figures for the last two films.) Boyhood had a lean budget of $200 thousand for each of the twelve years and totaling about $4 million with postproduction and other expenses added in. Still, as we shall see, the challenges really had nothing to do with the budgets.

I didn’t see Boyhood until the day after the Oscar ceremony, when it was still playing in our local second-run house. I was surprised to discover that it includes references to “Harry Potter,” though to the books, not the films. These are among the several pop-culture and historical references (the Obama-Biden lawn-sign scene, various popular songs) that cue us as to which year of the twelve we have reached.

Early on Olivia reads a passage from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets to Mason and Sam. We don’t see the cover of the book, but it’s a passage that clearly identifies which entry in the series it is. Chamber of Secrets came out in the USA on June 2, 1999. (Incredible as it now seems, the American releases of the first two books were roughly a year behind the British ones and didn’t reach a simultaneous release date until Goblet of Fire in 2000.) The kids are obviously fans, since later they wear costumes to attend the book-store release of Half-Blood Prince, which dates the scene precisely as July 16, 2005. I don’t think the use of Rowling’s series is a random choice. The first six books cover six years in the educations of Harry and his friends at Hogwarts, with the seventh and final one following their attempts to thwart the villainous Voldemort. All begin in the summer, often specifically including Harry’s July birthday. The first six end as the school year concludes, and at the climax of the seventh, Harry, Hermione, and Ron return to Hogwarts for Voldemort’s defeat.

Both Linklater’s feature and the “Harry Potter” film serial face the challenge of retaining the child actors across a lengthy period of shooting. Moreover, neither Linklater nor the “Harry Potter” filmmaking team started with a complete script. The script for Boyhood was written year by year, with input from the actors. The early “Harry Potter” films were made before Rowling had completed her books, and she seldom shared information about what would happen in the upcoming ones.

The boyhood of the Boy Who Lived

Much has been made of the fact that Linklater managed to keep Coltrane committed to the project to the end. Had he decided not to go on playing Mason, the project would presumably have ended. No one connected with the film has ever suggested that the film could have been finished. There was no option of forcing him to commit at the beginning to the full twelve years of shooting, since California law forbids film contracts lasting longer than seven calendar years. (The “De Havilland” law from the 1940s was based on a lawsuit by Olivia de Havilland that changed the Hollywood contract system forever, a story quite interesting in itself.) Given that constraint, however, the production signed Coltrane for the initial seven years and then gave him a second contract for five years. Legally there was one point at which he could have bailed, but presumably the filmmakers would not have forced him to stay with the project if he had badly wanted to stop.

Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter, played the supporting but important character of Sam. While Coltrane never wanted to quit, she at one point did, and Harry Potter was involved. The director revealed this last month in an interview in The Telegraph:

Ironically, it wasn’t Coltrane who rebelled against this extraordinary commitment, but Linklater’s own daughter Lorelei. Three years into shooting Boyhood, when she was coming up to 12, she asked her father, ‘Can my character die?’ ‘She wanted out,’ Linklater says now. ‘But that was just one year.’

He learnt the true story behind Lorelei’s rebellion only last month when they were in England, and visited the Harry Potter sets at the Warner Bros studio tour. In one scene in Boyhood, Mason and Sam dress up as their favourite Potter characters and go along to a midnight sale of the latest Harry book. ‘I had Lorelei dress as Professor McGonagall, though I think she wanted to be Hermione,’ Linklater recalls. ‘Those stories were so real in her life. She thought she was going to get a letter from Hogwarts saying she could go there. She thought she might date Harry Potter. Not Daniel Radcliffe, Harry. So I think us filming that scene felt to her that we were belittling that, invading her space. She couldn’t admit it then. But she can now.’ He shrugs, ‘It was a daughter-dad thing,’ he says. ‘Not actress and director.’

Given Linklater’s daughter’s intense involvement in the Harry Potter universe, one wonders if the idea for Boyhood was, at least unwittingly, inspired by Rowling’s creation. By the time the deal for support and casting of Boyhood was settled in 2002, four of the books and the first film had come out. Not that it’s important to my points here, but it’s intriguing. If true, then certainly Linklater took his own project in a completely different direction.

Obviously Linklater persuaded Lorelei to continue, which is all to the good of the film. Mason has a lot of troubles, and having his sister die probably would seem too great a bid for sympathy by the filmmakers.

On the other hand, the “Harry Potter” producers faced the real possibility of having to replace some of the child actors, given that a highly expensive and popular series could hardly shut down because, say, Daniel Radcliffe or Emma Watson decided to leave or came to look too old for his or her role. Certainly there are so many students at Hogwarts that the minor parts could have been recast without difficulty. At minimum, though, it was important to keep the central and the important supporting roles constant: Harry, Hermione, Ron, Fred and George, Ginny, Neville, Luna, and Draco. Obviously keeping the actors in the adult roles constant was desirable as well, though the one replacement that proved necessary didn’t scuttle the series.

Warner Bros., though prescient about approaching Rowling for the rights early on, had little evidence that the first book would be as successful in the US as it had been in the UK. In 2011, Rowling wrote an informative article about her relationship with the series’ main screenwriter, Steve Kloves, who penned all the scripts except for that of Order of the Phoenix. She describes her first meeting with him, just before going into lunch with a big studio executive. (This would have to have been in the period from late summer of 1997 to early autumn, 1998.) She mentions being wary about being introduced to Kloves.

He was going to butcher my baby. He was an established screenwriter, which was just plain intimidating. He was also American, and we were meeting shortly after a review of the first Potter book in (I think) the New Yorker, which had stated that it was unlikely the British idiom would translate to an American audience. You have to remember that my first Warner Bros. meeting did not take place against a backdrop of massive American success for the novels. Although the books were already very popular in the U.K., it was still early days in the U.S., and I therefore had no real means of backing up my opinion that American fans of the book would rather not have Hagrid “translated” for the big screen, for instance.

Odd though it seems now, the “Harry Potter” actors were initially contracted only for the first film. By number three, Prisoner of Azkaban, there was already talk of a change of the young central actors. Radcliffe remarked in an interview, when asked if he thought at the start that he would do all seven movies, “I was never sure I was going to do any of the films, other than signing on for the first and second. After that, it was always going to be: We’ll take it one film at a time.” This suggests that the contracts were made film by film throughout, and that Linklater had a better chance of retaining his main actors than the “Harry Potter” producers did.

There was in fact considerable talk during the production of the “Harry Potter” series that one or more of the child actors would be departing. (The quotations with dates in brackets below are from the imdb news pages for Daniel Radcliffe , which is a handy chronology of information concerning the film series, often excerpted from sites behind paywalls.)

[5 Sep 2002] Harry Potter star Daniel Radcliffe has resigned himself to growing out of the child wizard movie role–literally. The 13-year-old actor has finished filming the second installment of the adaptation of J. R. Rowling’s massively successful seven strong children’s book series, but his voice has already broken and he’s just had a growth spurt. He says, ‘In a couple of years, I might have changed so much that I look wrong for the part–even though Harry grows with the books.”

[22 Oct 2002] Another company of young actors is expected to take over the principal roles in the Harry Potter film franchise beginning in 2004 for the fourth movie, Chris Columbus, the director of the first two Potter movies, predicted Tuesday. Noting that the current stars, Danial Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint will all be teenagers next year, Columbus told Reuters. “If I were a betting man, I’d say they’ll probably stop after three.”

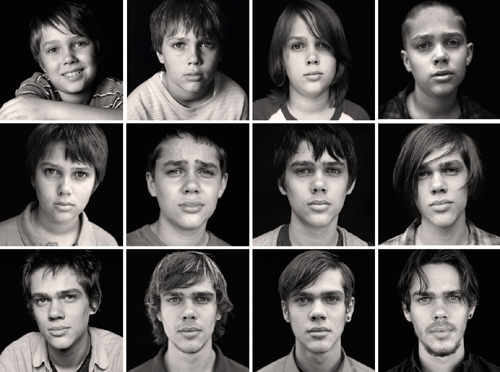

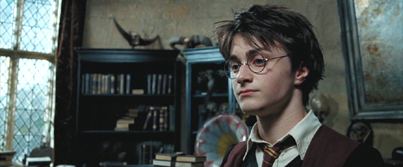

Indeed, the delays with the third film had allowed the cast to grow more than between the first and second, and the difference is quite obvious in Prisoner of Azkaban (above).

The producers perhaps realized by this point that, although the first two films had been released one year apart (Nov 2001 and Nov 2002), the pace could not be maintained. Indeed, the final film was released in July of 2011. This meant that although seven years of plot duration had passed for Harry and his friends, it took ten years for the films to come out. In most cases there was a one-and-a-half to two-year gap between releases, which came in November or June/July.

The following year there was renewed speculation, this time that the main children would be replaced for the fifth film:

[18 June 2003] Although analysts have suggested that the three young stars of the Harry Potter movies are quickly outgrowing their characters, the Reuter News Agency on Tuesday, citing an industry source familiar with the matter, reported that they will likely return for the fourth Potter film, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, due to be released in November 2005. By that time, Daniel Radcliffe, who portrays Harry Potter, will be 16 years old. Reuters quoted Seth Siegel, founder of The Beanstalk licensing and marketing consultancy group, as warning that if the stars are not replaced by younger actors, “licensing will fade away.” Wendi Green, an agent for child actors with Abrams Artists Agency, told the wire service, “If [they] are too old, kids can’t relate to it.”

Tom Felton, who played the young villain Draco Malfoy throughout the series, said in a 2011 interview that “We all feared that after the fourth film that they were going to get rid of us and start again with new kids. So yes, we’re very proud to have made it through.”

The rumors about the departure of Radcliffe or others continued fairly late into the series:

[4 March 2007] British actor Daniel Radcliffe’s representative has confirmed that he has signed on to start in the final two films in the Harry Potter series. […] The hit franchise, which continues with the fifth installment, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, later this year, has grossed $3.5 billion globally at the box office. Rowling recently announced that the seventh and final book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, will be published on July 21, but no film start date has been officially set.

Before the release of the final film, Kloves revealed that the departure of the main actors would have caused further upheaval in the series: “Emma was always the one who, we thought might leave, and I always said that if one of the kids left I would leave. And I would have because I only wanted to write for those three. I’m actually kind of amazed they all ended up doing it. It was the most important thing that happened to the movies.” Kloves’ continued participation obviously was crucial not just for keeping the series consistent in tone, but because he also had established a rapport with Rowling that gave her confidence that her books were being respected.

The filmmakers successfully retained all the significant child cast members, as well as many of the unnamed background figures, who are hard for even devotees of the books to identify. Only one moderately significant child actor was lost: Jamie Waylett, who played Vincent Crabbe, one of Draco’s two thuggish sidekicks/accomplices, dropped out before the final film. He had no choice, since the departure resulted from the first of several brushes Waylett would have with the law. This happened in April 2009, and he was in jail when the parts of Deathly Hallows began shooting simultaneously. Luckily Crabbe, although quite recognizable and prominent in a few scenes, is a fairly minor character (the chubby fellow seen below with Draco in the final scene of Philosopher’s Stone). Another Slytherin student, Blaise Zambini, introduced briefly in the the previous film, Half-Blood Prince, took over his function as the second of Draco’s two muscle-men. In all the commotion of the last film—and the fact that relatively little of the action takes place at Hogwarts–the substitution probably went unnoticed by most viewers.

This almost total stability among the child actors was fortunate, given how well the parts had been cast. The adult roles were equally well cast, with the exception of Richard Harris, who was already visibly feeble as Dumbledore in the first two films and could not realistically have been expected to make it through the series. His death led to Michael Gambon replacing him from the third film on, which seems to have had no adverse effect on the popularity of the films.

Thus the large cast of children for the “Harry Potter” series, with their short-term contracts, created a balancing act at least as great as that of keeping the two main child actors of Boyhood committed to the project until the end.

The end is not in sight

The first film, Philosopher’s Stone (aka Sorcerer’s Stone in the US), premiered in November, 2001. By that point, four of the seven books had been published, the most recent having been Goblet of Fire in July, 2000. The three remaining books, all very long, were still to come.

They were all, however, plotted. Anyone who has read the novels knows that they are maniacally intricate in their storytelling, with dozens of characters and hundreds of premises about Rowling’s invented world. People or things may be introduced early and return much later, only then being revealed as important. Gellert Grindelwald, for example, is mentioned on the back of the Dumbledore collectible card that comes enclosed with the chocolate frog that Harry buys in the first book. He is said to have been a Dark Wizard defeated by Dumbledore in 1945. That seems to be a mere bit of trivia until in the final book Grindelwald is revealed to have been a sort of predecessor Dark Lord to Voldemort, to have been a friend of Dumbledore’s in the headmaster’s unexpectedly shady youth, and a key figure in the fate of the Elder Wand, one of the three Hallows of the title.

Even knowing nothing about Rowling’s writing process, it’s obvious that she had to have worked the whole thing out in advance and in considerable detail. This was indeed the case: “Rowling conceived the idea for the series on a 1990 train ride. From the very beginning, she designed the books as a seven-book series. Rowling spent 5 years planning the plots and refining the characters before she ever started writing. She even wrote complete biographies of her characters prior to writing. Rowling is a careful and meticulous author, one who wrote no fewer than 15 drafts of the first chapter of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.”

So when Rowling met Kloves at the meeting described above, she already knew much about how the series would proceed and end. Once the scripting process began, Rowling made herself available for consultation by Kloves via email and occasionally attended script meetings. What she did not do was tell Kloves what would happen in the upcoming books:

Steve would ask me questions, sometimes about the background of the characters, sometimes on whether something he’d had one of them say or do was consistent with what had happened to them or what would happen. He very rarely took a wrong turn; in fact, I’m struggling to remember any occasion when he did. He had a phenomenal instinct about what each character was about; he always plays that down, but he made some very accurate guesses about what was coming.

Actually, I’ve just remembered the only time he did get something wrong, and it was a funny one. We were at a script read-through for Half-Blood Prince at Leavesden, so for once we were side-by-side in the same room. I hadn’t read the very latest draft, so I was hearing it for the first time. When Dumbledore started reminiscing about a beautiful girl he’d known in his youth, I scribbled “Dumbledore’s gay” on my script and shoved it sideways to Steve. And we both sat there smirking for a bit.

I don’t think he ever pushed to know what was coming next. Odd, really, when I look back; except that I’ve got a feeling that as a fellow writer, he understood that I needed some space. There came a point where my bins were being searched by journalists; keeping tight-lipped was a way of giving myself creative freedom. I didn’t want to be tied down by expectations I’d raised; I wanted to be at liberty to change my mind. But I did tell Steve a few things. I used to share what I was doing as I was doing it. I remember emailing him while writing Goblet of Fire and telling him that I had backstory on Hagrid that I wanted to put in, but I was wondering whether it wasn’t too much, given how big the novel was likely to be. He emailed back saying, “You can’t tell me too much about Hagrid. Put it in.” So I did.

(On the later public revelation of Dumbledore’s being gay, see here.)

In making Boyhood, Linklater knew how many years he would work, but he was writing the script himself when he went along. He adjusted the story to suit the changes in his main actor. In real life, Coltrane became interested in photography, so Linklater made it part of his character. There was no set plot, just a timeline. And despite how much Coltrane’s looks changed as he grew, he never could be inappropriate to the role, for he defined and determined that role.

The same was not true for the Potter cast. No one could predict what they would look like in ten years and whether it would fit what happened to their characters in an unknown plot that had already been extensively planned out.

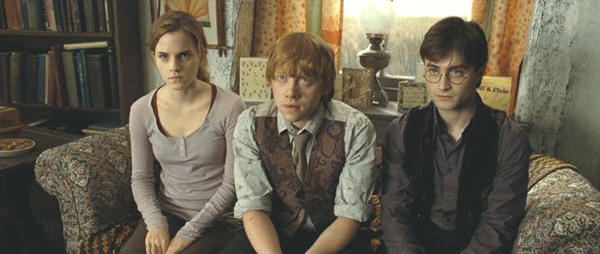

Yet on the whole, the filmmakers were consistently lucky. The changes worked. While all three of the main characters started out very cute (see top, Philosopher’s Stone), as they grew, Grint, as Ron, lost that cuteness. His rather plain looks fit well with his increasing jealousy of Harry, which is especially important in Goblet of Fire (below left) and Deathly Hallows Part I. Radcliffe kept much the same basic look as he matured, with cute becoming cutely handsome (below right in Prisoner of Azkaban). Watson blossomed into a beautiful young woman, as suddenly revealed to the other characters in the ball scene of Goblet of Fire (above).

The same turned out to be true of the supporting characters. Felton as Draco began in The Philosopher’s Stone as a spoiled brat (at left below wearing one of the black pointed wizard hats that were true to the book but wisely discarded for the rest of the film series). He effectively became a tormented, would-be killer who slowly develops a conscience (below right, in Half-Blood Prince).

Bonnie Wright plays Ginny Weasley, who begins as a shy girl so impressed by Harry that she can’t utter a word in his presence (their first meeting in Chamber of Secrets, below left). Four years of real time later, in Goblet of Fire, she barely looks any older (below right), and the filmmakers might have worried that she would not mature enough by the end of the series to appear plausibly old enough for Harry to fall in love with and marry:

On the other hand, this works quite well with the book’s action, where Ginny, being a year behind the others–a third-year rather than a fourth-year–could not go to the ball at all unless she had a fourth-year as a date, and she accepts Neville after Hermione turns him down. In the book, Ginny somewhat regrets her choice, in that clumsy Neville keeps stepping on her feet as they dance. In the film, the fact that Ginny looks so young here makes it difficult to imagine that she and Neville should be taken seriously as a potential couple.

Again luck was with the filmmakers, and Wright was a young woman in time for the romance depicted in the book to develop (below in Deathly Hallows Part I).

Undoubtedly, though, the filmmakers’ most impressive stroke of unforeseeable casting luck was with Matthew Lewis as Neville Longbottom. Neville first appears early in Philosopher’s Stone, where he is quickly established as the class dork. On the train to Hogwarts he has lost his pet toad, and once in school he turns out to be clumsy, forgetful, totally lacking in confidence, and bad in classes, all of which make him seem doomed to remain a conventional comic figure. The young Lewis, with his chubby cheeks, buck teeth, and timidly wary expression (below, in Philosopher’s Stone) embodied the role perfectly.

Rowling carefully motivates the gradual emergence of confidence in Neville. In the scene just above, from the climactic scene, Dumbledore is handing out extra points, upon which winning the Class Cup for the year depends. Predictably, Harry, Hermione, and Ron get 50 each for their heroic actions in foiling Voldemort in his attempt to return to bodily form. But Neville, who had failed to talk them out of their dangerous endeavor, gets ten points for the bravery displayed by his effort–the ten needed to put Griffindor into first place. He’s stunned by this (above), but in the second book (and film) it seems not to have bolstered his confidence much. In the third book, Prisoner of Azkaban, Neville manages under Lupin’s guidance to defeat the shape-shifting boggart–his first classroom success (in the film, below left, where Lewis is already almost unrecognizable compared to his earlier self). In the next book, Goblet of Fire, we begin to get hints at Neville’s tragic past: his parents, heroic figures in the earlier struggles against Voldemort, were tortured into insanity, and he has been raised by a demanding grandmother who has little patience with his shortcomings. (This past is sketched much more briefly in the film series.)

Later he discovers that he has an aptitude for herbology (something made explicit in the book but not in the film series, though there Neville does show up one year carrying a rare plant rather than his toad). In Goblet of Fire he takes Ginny to the ball (above). In Order of the Phoenix, once the dire Dolores Umbridge starts taking over Hogwarts with her Orwellian rules and her plans to replace Dumbledore, Harry agrees to teach the other students how to defend themselves against the Dark Arts. After a rocky start, Neville (who has become considerably taller than Harry) slowly and with grim determination manages to learn the important spells that “Dumbledore’s Army,” as they call themselves, will need in the struggles to come (below right).

Ultimately Neville becomes one of the heroes of the final battle against Voldemort. During the last two books/three films, Dumbledore and Harry, and after Dumbledore’s death, Harry, Ron, and Hermione, have been seeking and destroying horcruxes (six mysterious objects into which Voldemort has hidden parts of his soul in an attempt to achieve immortality). Five have been destroyed by the main trio, but it is Neville, standing before the shattered courtyard of Hogwarts, who defies Voldemort and destroys the sixth horcrux. This makes it possible for Harry to kill Voldemort.

Lewis turned into a handsome young man, thoroughly appropriate for the new determined and heroic Neville. (Lewis’ unexpected change has been much commented upon on the internet, of course. See here, here, and here. There is considerable gushing involved.) The most optimistic casting director could not have had a clue as to how the eleven-year-old Lewis would transform to fit the end of his character’s arc, especially given that that arc was completely unpredictable to all but Rowling.

(It’s a pleasure to know that in the book he becomes the professor of herbology at Hogwarts, though there’s no mention of this in the film.)

Here I think we see the film’s greatest advantage over the book, and perhaps it took Boyhood to make us fully realize it. Rowling, though not much of a stylist, creates a vast and complex plot, and in the books we get to experience all of it. She is adept at portraying a wide range of intriguing and entertaining characters, and the dialogue she gives them flows easily and suits them. Much of this had to be cut or compressed for the films, long though they are.

Any literary adaptation into film allows us to see settings, characters, and actions that the book cannot portray visually. In the case of the “Harry Potter” series, the design of the Quidditch stadium brought that sport to life and special effects made non-human characters like Dobby and Kreacher seem real. But ultimately the actors and their changes over time added something even more important that the characters as written could never have. Kloves recalls an early meeting: “I remember sitting in an office 10/11 years ago with Lorenzo de Bonaventurea [producer of, among others, the Transformers series], David Heyman [producer of the “Harry Potter” series] and Chris Columbus [director of the first two “Harry Potter” films] and we were having this 15 minute conversation about special effects. I said, ‘You guys, the special effects you’re gonna have is those kids. Cast those three kids right and it’ll never end but if you miss, forget it. It’ll never work.”

Unfortunately the growth of the characters over seven years is somewhat undercut by the “19 years later” epilogue of The Deathly Hallows. In the novel, it’s tolerable, since we simply imagine them as older. Still, I would have preferred to do without it, even if it meant not learning about Neville’s professorship and Harry’s son being named Albus Severus Potter, both satisfying final touches. But in the film, the actors, after we’ve watched them actually grow for the seven years of attending Hogwarts and for the ten years of the production, simply cannot suddenly leap into their later 30s. Some of the actors look vaguely plausible in their old-age makeup (Radcliffe somewhat, Watson not in the slightest), but it’s jarring to see them trying to play considerably older. The epilogue should definitely have been dropped from the film, though I realize that Rowling is inexplicably attached to it.

March 21, 2015: Thanks to Antti Alanen, who informs me that there was a Finnish six-film series, Suomisen perhe (“The Family Suominen”), made from 1941 to 1959. One of the family members, Olli, was played by Lasse Pöysti, who went from age 13 to 32 in the course of the series and became a major Finnish actor. Antti says that critics of the period compared Suomisen perhe to the Andy Hardy series.

December 30, 2016: A screen test involving Racliffe initially and then all three of the child actors, is available on YouTube. All three are visibly younger than in the first film, but one can see why they were cast.