A legendary film returns from the realm of the lost

Wednesday | April 8, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here-

Nearly two years ago, when Flicker Alley released its wonderful collection of French films made by the Russian-emigré production company Albatros in the 1920s, I wrote, “Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful.” That release arrived yesterday.

For decades, La Maison du mystère remained one of the fabled lost films of the silent era. It was an enormous popular success upon its release in 1923, and critics praised it as well. Even Louis Delluc, who highmindedly promoted cinema as a realistic, restrained art, grudgingly said of it, “La Maison du mystère is a serial. They are a necessity. So be it. This one is intelligent, sober, frank, genuinely human.”

Watching the film today, “sober” seems an odd term. Despite its many arty moments, the film presents a conventionally melodramatic story, with Mosjoukine playing a struggling factory owner betrayed by a villainous “friend” who is secretly in love with his wife. He is falsely accused of murder, presumed dead after an escape from hard labor, and operates under various disguises. Blackmail, flashy escapes, a suicide pact, and flagrant coincidences all play roles. Yet in contrast to the fantastical ones of Louis Feuillade from the 1910s, the ones we are most familiar with today, Le Maison du mystère paid more attention to characterization and moved at a less breakneck pace. (Feuillade had moved into this sort of dialogue-centered melodrama himself in the 1920s, as in Les Deux Gamines, 1921, but these films are rarely watched today.)

With Alexandre Volkoff directing the script he and Mosjoukine adapted from a popular novel, filming began in the summer of 1921. At the beginning of 1922, Mosjoukine contracted typhoid fever and was out of commission for six months. Shooting was completed in the summer of 1922, and the film was released in ten weekly episodes starting in March of 1923. Ultimately, like so many silent films, it disappeared.

Severely abridged feature-length versions existed in some places. An 18-reel print discovered in the Iranian archive was destroyed in a fire before it could be sent to France for restoration. Luckily, the original negative turned up at the Cinémathèque française, having been donated in the collection of Alexandre Kamenka, the producer who took over Joseph Ermolieff’s company in 1922 and turned it into Films Albatros. After restoration, the film was shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in 2002–well before we began our annual visits to that festival in Bologna. It was presented again at the Museum of Modern Art in 2003.

The Flicker Alley release runs 383 minutes and seems to be essentially complete, although the intertitles apparently are replacements. Unlike so many restorations derived from worn release prints, this one is visually gorgeous. It’s mostly in black and white, though it has appropriate tinting for fire and night scenes. Neil Brand provides an excellent piano score.

The old and the new

Like so many of the major French films of the 1920s, especially the Impressionist ones, La Maison du mystére combines a sentimental, old-fashioned story with unconventional stylistic devices: unusual pictorial motifs, beautiful cinematography and design, and imaginative staging. It is probably this visual interest that led to the film’s original acceptance by reviewers and to its enthusiastic reception by modern historians and silent-film buffs.

One visual motif that begins early on is silhouettes. The opening involves Mosjoukine’s character, Julien, still a bumptious, naive young man, courting Régine, the daughter of a wealthy couple who live near his chateau (the “maison” of the title). Despite his shyness, they manage to become engaged and walk joyfully through the woods together.

The entire wedding scene is then compressed into a series of shots done against bright white backgrounds render the actors and settings in near-black silhouettes (above). The result looks like a live-action version of a Lotte Reiniger cut-out animated film.

As I discussed in my entry on the Albatros DVDs, the settings in the studio’s films tended to be impressive as well. Here much of the interest is created by actual locales. David speculated that the whole film was conceived around the ruined fortress or castle where several scenes take place. That’s not likely, but the filmmakers used the ruins well. Rudeberg, a woodcutter whose penchant for amateur photography leads him to photograph the murder of which Julien is falsely accused and convicted, hides the prints in this castle. Rather than turning them over to the authorities, he is using them to blackmail the real murderer, the factory manager Corradin. Corradin twice follows him to the castle, leading to dramatic compositions of the two men in different parts of the frame. In the image at the top, Corradin slinks along the row of arched doorways at the bottom, while Rudeberg is visible moving through a higher archway at left center.

Alexander Lochakoff, the main designer for Ermolieff and then Albatros, was somewhat restricted by the story. He needed to provide realistic interiors for an antique-filled chateau rather than the modern apartments in which some of the other Albatros films take place. Still, he managed some characteristic designs, such as the prison corridor at the bottom of this entry, a location seen only in one brief shot.

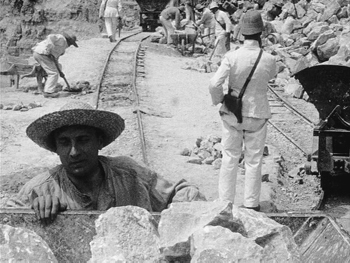

There are some brilliant moments of staging in depth. After Julien is sentenced to twenty years of hard labor, his new situation is introduced via a tracking shot with the camera atop a cartload of stone which he is pushing. Gradually the laborers breaking stone and the guards overseeing them are revealed (below left). In another shot in the ruins where Corradin is tailing Rudeberg, he is glimpsed in the background (below right).

In a scene late in the film, Julien plans to flee with Régine and their daughter Christiane. He is dressed as their chauffeur, but Corradin shows up and spots the car. Julien hides and watches him from behind a tree in the foreground.

We then see the two women approaching, framed through the back window of the car and watched by Corradin, in the foreground. He ducks down and pretends to fiddle with the car’s engine to prevent their realizing who he is as they draw near.

I could go on illustrating such stylistic flourishes, but I leave it to you to find them for yourself. There’s a very early example of a montage sequence to compress the passing of World War I into a series of titles, from 1914 to 1919, superimposed over stock footage of combat, and a marvelously choreographed high-angle scene in a forest as a troop of policemen pop out of nowhere to surround and arrest Julien.

All serials need stunts

Much of the film consists of conversations and confrontations among the characters, a trait which no doubt led critics to contrast the more action-oriented serials of recent years. Still, there are two sequences where derring-do takes over. After the police arrest Julien, he makes an escape via a rope down the tower and wall of his chateau, a feat accomplished in a single take tilting down to follow his progress.

Later, in an episode entitled “The Human Bridge,” Julien and four of his fellow prisoners escape from their guards while working on a railroad track. This lengthy sequence involves first the commandeering of a passing train and then a chase over an area of rocky crags. At once point the escapees find the rickety remains of a tall bridge above a river gorge and fling ropes across. The four other prisoners then lie end to end, clinging to the ropes, forming a bridge to allow Julien, who has been wounded during their flight, to cross over. One extreme long shot of the scene shows two of the men’s hats falling off, demonstrating as they drift down to the bottom that there is no trick photography involved. It is certainly as impressive as any of the stunts in Feuillade’s films.

Touches of Impressionism

La Maison du mystère certainly cannot be characterized as an Impressionist film. Yet the movement was beginning to expand in 1921, and there are some moments of subjectivity that draw upon its newly minted conventions. As his trial is drawing to an end, Julien closes his eyes, and the shot goes out of focus. We see a series of quickshots of his surroundings and his family as he seemingly recalls the events of the trial as a montage scene. Finally the same framing of Julien shows him coming into focus.

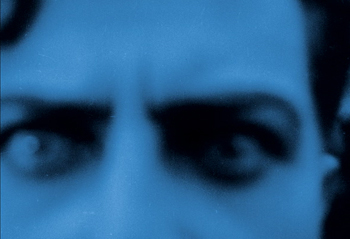

This is a fairly straightforward Impressionist device, but a more daring suggestion of a subjective state occurs much later. Julien’s daughter Christiane and Rudeberg’s son Pascal have fallen in love, and they vow that if they cannot marry each other, they will both commit suicide. When the villainous Corradin forces Christiane to agree to marry him, Pascal sets out to drown himself. His distraught state of mind is conveyed in a single shot as he walks toward the mill pond and hesitates. As he moves into the shot, he is framed in a standard medium close-up. As he hesitates, however, he moves unusually close to the camera and then backs partway out of the frame, as if afraid to continue. Finally he turns and stares into the camera, moving forward out of focus until his dark-shadowed eyes fill the frame. The implication is that he determines to go on with his plan.

(Fans of Evgeni Bauer will recognize Vladimir Strizhevski, the son in the director’s final film, The Revolutionary.)

Star turn

Apart from the imaginative staging, cinematography, and design, La Maison du mystère is full of fine performances. It provides a vehicle for a virtuoso performance by Mosjoukine. He is part Douglas Fairbanks, part Lon Chaney as he leaps energetically about in the early parts of the film and then dons various disguises during his long period as a fugitive. He briefly poses as a clown in a small circus and later returns to work incognito in his own factory as a wounded war veteran with a limp and eye-patch.

Mosjoukine’s fellow actors refuse to be overshadowed by the star, with Hélène Darly as Régine managing somehow to age from a young lady to a mature mother without any apparent change of makeup. Nicolas Koline, best known as Tritan Fleuri in Napoléon vu par Abel Gance, brings something of his usual comic persona to Rudeberg, while also conveying the character’s guilt over choosing to use his photographs for blackmail purposes rather than to reveal Julien’s innocence. Charles Vanel, who had been acting in films since 1910 and would become a major star in the sound era, conveys Corradin’s villainy perhaps too well, making one wonder why any of the other characters ever trusted him.

Flicker Alley, along with the Cinémathèque française, David Shepard, and Lobster Films, have filled in a major gap in film history, and we are indeed doubly grateful.

The quotation from Louis Delluc and information on the production of the film come from the essay, “The Art Film as Serial” by Lenny Borger with David Robinson, included as a booklet in the DVD set.

Impressionist films have been included in some of our “best films” of ninety years ago series. See 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.