Archive for April 2015

Local Boy Makes Very, Very Good: Welles comes home

DB here:

Nearly a hundred years ago George Orson Welles was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The story goes that when the UW—Madison asked him to come get an honorary degree long afterward, he refused. The reason? He claimed he was conceived in Rio de Janeiro, so he considered himself Brazilian.

About ninety years ago, little Orson went to Indianola summer camp outside Madison. (A memoir of his stay, criticizing Welles’ more lurid version, is here.) He attended fourth grade in Madison 1925-1926. At that time he was studied as a child prodigy by psychologist Dr. F. G. Mueller. A story about the little rascal, who was already staging plays, appeared in a local paper. Then he transferred to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois.

About ninety years ago, little Orson went to Indianola summer camp outside Madison. (A memoir of his stay, criticizing Welles’ more lurid version, is here.) He attended fourth grade in Madison 1925-1926. At that time he was studied as a child prodigy by psychologist Dr. F. G. Mueller. A story about the little rascal, who was already staging plays, appeared in a local paper. Then he transferred to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois.

Madison has done pretty neatly by him. Our Wisconsin State Historical Society collections include some Wellesiana: production material on Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, and unmade projects, along with a rich trove from Agnes Moorehead, who taught school in Soldiers Grove and got a Masters at our university. For decades, Welles’ films were staples of our bustling campus film-society scene, and out of that emerged Wisconsin-born Joseph McBride. Joe produced a fine critical monograph on Welles in 1972 and has been writing about him ever since. Another supremo Wellesian, James Naremore, did his doctorate here. Douglas Gomery, one of our Film Studies alumni, wrote a foundational study of Welles’ relation to the studio system, and Michael Wilmington, who collaborated with Joe on a book on John Ford, has also written eloquently on Welles over the years.

So I had good luck coming here in 1973. As a teenager getting interested in film, I focused most avidly on Welles. I watched Kane and Ambersons on late-night TV, and as a good omen, there was a 16mm screening of Kane during my first week as a college freshman. With pals I traveled to New York to see the newly released Chimes at Midnight (twice) and wrote a review for our student newspaper. A few years after that Film Comment published my first serious piece of film criticism, an essay on Kane. That movie has been a leitmotif of my life—a centerpiece of our textbook Film Art since its publication in 1979, important in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and still stubbornly facing me down in my current struggles with 1940s Hollywood narrative.

So it’s in the nature of things that our Cinematheque is honoring Welles in a year-long retrospective that started in January. And it’s even niftier that our current Wisconsin Film Festival has included three items celebrating this prodigious and prodigal Cheesehead.

Never too much johnson

I like quick cutting very much. I didn’t do much of it at the start. But the more I work, the more I like it.

Orson Welles

Welles shot film material to fill in exposition for the three acts of a stage production he was mounting in 1938. Too Much Johnson was a revival of a turn-of-the-century farce, and how the smart-alecky boys must have snickered at the title. The film remained uncompleted and was never shown with the play (which failed out of town). Welles edited the first part of the footage to some extent, but what remains of the rest are rushes. The footage was discovered in Pordenone, Italy in 2008 and has recently become available for screenings. You can watch it on Fandor, though we discovered that it plays best on the big screen with an audience and live music. For us, piano accompaniment was supplied by the versatile David Drazin.

Movies have long been mixed with live performance. Early films were inserted between vaudeville acts. In Japan, films enhanced and extended the action of plays. Eisenstein famously insinuated comic footage into his 1923 Moscow production of The Wise Man, and the idea caught on in Europe as well. By 1938, the New York stage had its own tradition of mixed-media, notably in the “Living Newspapers” sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. Welles had played in another politically pointed production, Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936), which incorporated both slides and film.

The Too Much Johnson footage is a tribute to silent movies, or at least silent movies as a young theatre director in 1938 thought of them. At that time, many intellectuals admired slapstick comedy; serious silent drama was largely considered old-fashioned and “theatrical.” Movie aficianados also appreciated the silent avant-garde, especially Clair’s Entr’acte (1924), which enjoyed a place in the crystallizing Museum of Modern Art canon. Entr’acte, another movie inserted in bits during a stage show (Rélâche), was itself a reworking of American chase-and-stunt extravaganzas. I think the Too Much Johnson material bears traces of both Hollywood and Paris, especially with certain cuts that are even bolder than what we’d find in Sennett or Lloyd.

Welles scrambles several trends of silent cinema. To evoke the period of Gillette’s 1894 play, an early scene suggests filmed theatre before 1908 or so, but Welles immediately interrupts it with very brief, looming close-ups.

Elsewhere, Welles provides a flurry of Soviet-style axial cuts when the couple are interrupted in bed.

These “concertina” cuts, along with the mismatches of a twisting Joseph Cotten, create a jumpy effect reminiscent of Kuleshov’s By the Law (1925) and other films. (Though I doubt that Welles had seen that.)

There’s also a lot of Soviet-style Eccentrism in the opening footage, with Cotten scrambling over buildings and through a market in the Harold Lloyd manner. At both a pastiche and a potpourri, Too Much Johnson stands as something more than a curiosity. It’s a sketchbook, a finger-exercise in silent cinema technique, and a testament to buoyant youth from a twenty-three-year-old. It’s also evidently the first of Welles’ many unfinished films.

Noble artificiality

Chuck Workman’s Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles has the good sense not to get in the way of Welles’ overwhelming presence. The documentary smoothly incorporates many interview clips with Himself and collaborators, kin, and admirers. There are also some splendid family photographs. The structure is chronological, and clips from the film are surrounded by contextualizing commentary from Welles and others. There’s a wonderful moment when Workman illustrates, with production photos, the dead silence following the Martians’ attack in Welles radio drama. The documentary even manages to throw doubt on Welles’ reminiscences by juxtaposing contradictory interview statements. I have a hunch that Jim Naremore, who was the major consultant on the project, encouraged this sort of historical frankness. Every Welles researcher knows that against his selective memory and penchant for fabulism, the documents must be checked.

Among the familiar but always compelling landmarks, Norman Lloyd makes a comment that set me thinking. “He brought, in one word, theatricality.” Welles was a sponge, blending many of the innovations in staging and conception that streamed into America from overseas, but I think he was particularly marked by what was then called “theatrical theatre.”

Among the familiar but always compelling landmarks, Norman Lloyd makes a comment that set me thinking. “He brought, in one word, theatricality.” Welles was a sponge, blending many of the innovations in staging and conception that streamed into America from overseas, but I think he was particularly marked by what was then called “theatrical theatre.”

The Europeans, notably Piscator, and the Russians, notably Meyerhold, had embraced frank artifice. They challenged all forms of realism, from the bland ignore-the-fourth-wall parlors of the well-made play, to the Naturalist notion that the play was a “slice of life” and that you could hang bleeding cuts of meat in your stage-set butcher shop. They also challenged the atmospheric Symbolism of Appia and others. Instead, theatrical theatre offered a stripped-down presentation that broke with the proscenium and hurled itself at the audience. The stage space was no longer a room or imaginary world cut off from the audience; it was of a piece with the auditorium. Performances were no longer representational, but “presentational,” in the manner of jugglers, acrobats, or…magicians.

For Americans, the idea of Theatrical Theatre was crystallized in Mordecai Gorelik’s book New Theatres for Old (1940). Gorelik traced the trend from Toller’s Masse Mensch (1921) directly to Welles’ 1937 “no-scenery” production of Julius Caesar. Other productions of that season, including The Cradle Will Rock (Welles and Houseman, using a bare stage perforce) and Our Town, with its scripted catcalls from the audience, were turning the blank stage into a space continuous the auditorium—not an imaginary locale but an area for acting and interacting.

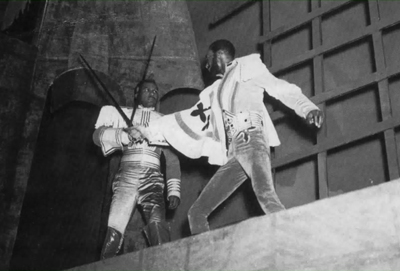

Gorelik quotes Gordon Craig: “Do not forget that there is such a thing as noble artificiality.” Not a bad summation of Welles’ productions, including the Harlem Macbeth (above) and the War of the Worlds broadcast, as well as the films. Theatrical theatre is confrontational, sometimes angrily and sometimes, as in Welles’ penchant for reviving vaudeville, good-naturedly. Even Gorelik couldn’t go along with Mercury’s 1937 Faustus, which he deprecated as a “sleight-of-hand performance.” But I think it’s plausible to take Welles as in the tradition Lloyd alludes to. Expecting realism blocks some people from appreciating the brazen stylization, the pranksterish poke in the eye we get from many of the movies.

Hearts of age

Over the last thirty years or so, I remembered Chimes at Midnight as a more cohesive movie than the admirably choppy Othello. Seeing Chimes again yesterday, I realized that they were mates. There was the same ransom-note assemblage of scenes, the abrupt cutaways covering changes in character position, the use of long shots showing characters not speaking the lines we hear them say. You hear a line and may find that nobody has opened his mouth. An empty tavern becomes suddenly full after we’ve hung around one area of it. The great battle scene starts out making sense spatially but then dissolves into chaos, as men grind and hammer one another, and the dust at their feet turns to bloody mud.

So what? One of the lessons Welles seems to have learned from Eisenstein is that continuity is overrated. Almost every shot-change forces you to readjust your attention, and a cut is less a link than a jolt. André Bazin was right to praise Welles’ long takes, but the Wonder Boy of the 1940s also loved disjunctive cuts, apparently from Too Much Johnson onward. Not all the harsh editing in The Lady from Shanghai and Macbeth can be attributed to studio interference. By the time we get to Othello, the same paste-up aesthetic governs almost every scene, with sound sometimes covering the gap and sometimes accentuating it.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that only the Greeks and the French classicists wrote true tragedies. Tragedy ought to be austere and pure, he seems to have thought. Shakespeare, he insisted, gives us high-level blood-and-thunder melodrama. So his Shakespeare films are rough and tumble, full of violent, strident effects, from the brimstone paganism of Macbeth to Othello’s Turkish-bath assassination. Here, it’s Falstaff and his followers providing earthy comedy, with Prince Hal enjoying the riotous living and the escalating slanging matches, where punning insults are swapped between gulps of sack. The glowing Boar’s Head versus the spare, chilly palace; fiery Fat Jack versus severe, monastic Henry IV; romps in the forest versus carnage on the battlefield—these are the options facing the young prince. Playing, as we now say, the long game, he warns Falstaff twice that when he assumes power, the old rogue will be cast off. When the new king follows his father’s advice “to busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels” (sound familiar?), you have to wonder if an occasional robbery of pious pilgrims is worse than Henry V’s cynical venture into patriotic gore: “No King of England if not King of France!” Falstaff, cold as any stone, is hauled off to his grave. Melodrama, again, and none the worse for it.

Thanks to Jared Case of George Eastman House who brought Too Much Johnson to us and provided lively commentary. Eastman House is the archive that restored the film, and is the site of The Nitrate Picture Show starting 30 April. (See you there?) Thanks as well to Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King of our festival for many varieties of help. They do a swell job.

Frank Brady interviewed Welles extensively about the Too Much Johnson project, and the informative results are in Brady’s Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles, 145-151.

The Wisconsin Film Festival runs until 16 April, and there are many high points yet to come—not least, a 35mm screening of Where the Sidewalk Ends (15 April), which Kristin and I must miss (snif). The Cinematheque series continues this summer with a focus on Welles the actor, and in the fall with several rarities.

Of the many, many Welles celebrations this year, the Indiana University one later this month will surely be the lollapalooza.

Douglas Gomery’s trailblazing article, arguing that Welles was a prototype of the Hollywood independent, is “Orson Welles and the Hollywood Industry,” Persistence of Vision 7 (1989), 39-43. On Too Much Johnson, see Joe McBride’s in-depth piece at Bright Lights. There are too many excellent books on Welles to itemize here, but at the very least your shelf needs Peter Bogdanovich and Jonathan Rosenbaum’s This Is Orson Welles, Jim Naremore’s Magic World of Orson Welles, Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?, Jonathan Rosenbaum’s Discovering Orson Welles, and Simon Callow’s luxuriant two-volume biography. The most complete account of Welles’ stay in Madison that I know is in Peter Noble’s The Fabulous Orson Welles, pp. 26-33. The article about the Boy Wonder, age ten, appeared in The Capital Times (19 February 1926). Welles talks about Shakespearean plays as melodrama in the third audiocassette accompanying This Is Orson Welles, at 52:02.

Our analysis of Citizen Kane occupies chapters 3 and 8 of Film Art, and chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. There are many references to Kane and Ambersons on this site; check the Welles category. My 1967 review of Chimes at Midnight is here, on p. 9. It’s all too obviously the work of a twenty-year-old, and it demonstrates how it’s not really that hard to write a passable movie review. But at least it’s enthusiastic about the right things.

P. S. 13 April 2015: Joe McBride writes:

And Madison Mafia made man Pat McGilligan’s upcoming biog Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane will have many illuminating things to say about OW’s Madison days, as well as correcting other myths.

Thanks to Joe and best wishes to Pat, whose book will appear in August. For background on the Madison Movie Mafia, go here.

P.P.S. 13 April 2015: Manfred Polak advises me that the copy of Too Much Johnson that I linked is blocked for some regions of the world. It’s available for all on National Film Preservation Foundation pages. The complete 66-min. work print we saw in Madison is here and can be downloaded here. There’s also a 34-min. edited version, downloadable here.

Thanks very much to Manfred!

A legendary film returns from the realm of the lost

Kristin here-

Nearly two years ago, when Flicker Alley released its wonderful collection of French films made by the Russian-emigré production company Albatros in the 1920s, I wrote, “Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful.” That release arrived yesterday.

For decades, La Maison du mystère remained one of the fabled lost films of the silent era. It was an enormous popular success upon its release in 1923, and critics praised it as well. Even Louis Delluc, who highmindedly promoted cinema as a realistic, restrained art, grudgingly said of it, “La Maison du mystère is a serial. They are a necessity. So be it. This one is intelligent, sober, frank, genuinely human.”

Watching the film today, “sober” seems an odd term. Despite its many arty moments, the film presents a conventionally melodramatic story, with Mosjoukine playing a struggling factory owner betrayed by a villainous “friend” who is secretly in love with his wife. He is falsely accused of murder, presumed dead after an escape from hard labor, and operates under various disguises. Blackmail, flashy escapes, a suicide pact, and flagrant coincidences all play roles. Yet in contrast to the fantastical ones of Louis Feuillade from the 1910s, the ones we are most familiar with today, Le Maison du mystère paid more attention to characterization and moved at a less breakneck pace. (Feuillade had moved into this sort of dialogue-centered melodrama himself in the 1920s, as in Les Deux Gamines, 1921, but these films are rarely watched today.)

With Alexandre Volkoff directing the script he and Mosjoukine adapted from a popular novel, filming began in the summer of 1921. At the beginning of 1922, Mosjoukine contracted typhoid fever and was out of commission for six months. Shooting was completed in the summer of 1922, and the film was released in ten weekly episodes starting in March of 1923. Ultimately, like so many silent films, it disappeared.

Severely abridged feature-length versions existed in some places. An 18-reel print discovered in the Iranian archive was destroyed in a fire before it could be sent to France for restoration. Luckily, the original negative turned up at the Cinémathèque française, having been donated in the collection of Alexandre Kamenka, the producer who took over Joseph Ermolieff’s company in 1922 and turned it into Films Albatros. After restoration, the film was shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in 2002–well before we began our annual visits to that festival in Bologna. It was presented again at the Museum of Modern Art in 2003.

The Flicker Alley release runs 383 minutes and seems to be essentially complete, although the intertitles apparently are replacements. Unlike so many restorations derived from worn release prints, this one is visually gorgeous. It’s mostly in black and white, though it has appropriate tinting for fire and night scenes. Neil Brand provides an excellent piano score.

The old and the new

Like so many of the major French films of the 1920s, especially the Impressionist ones, La Maison du mystére combines a sentimental, old-fashioned story with unconventional stylistic devices: unusual pictorial motifs, beautiful cinematography and design, and imaginative staging. It is probably this visual interest that led to the film’s original acceptance by reviewers and to its enthusiastic reception by modern historians and silent-film buffs.

One visual motif that begins early on is silhouettes. The opening involves Mosjoukine’s character, Julien, still a bumptious, naive young man, courting Régine, the daughter of a wealthy couple who live near his chateau (the “maison” of the title). Despite his shyness, they manage to become engaged and walk joyfully through the woods together.

The entire wedding scene is then compressed into a series of shots done against bright white backgrounds render the actors and settings in near-black silhouettes (above). The result looks like a live-action version of a Lotte Reiniger cut-out animated film.

As I discussed in my entry on the Albatros DVDs, the settings in the studio’s films tended to be impressive as well. Here much of the interest is created by actual locales. David speculated that the whole film was conceived around the ruined fortress or castle where several scenes take place. That’s not likely, but the filmmakers used the ruins well. Rudeberg, a woodcutter whose penchant for amateur photography leads him to photograph the murder of which Julien is falsely accused and convicted, hides the prints in this castle. Rather than turning them over to the authorities, he is using them to blackmail the real murderer, the factory manager Corradin. Corradin twice follows him to the castle, leading to dramatic compositions of the two men in different parts of the frame. In the image at the top, Corradin slinks along the row of arched doorways at the bottom, while Rudeberg is visible moving through a higher archway at left center.

Alexander Lochakoff, the main designer for Ermolieff and then Albatros, was somewhat restricted by the story. He needed to provide realistic interiors for an antique-filled chateau rather than the modern apartments in which some of the other Albatros films take place. Still, he managed some characteristic designs, such as the prison corridor at the bottom of this entry, a location seen only in one brief shot.

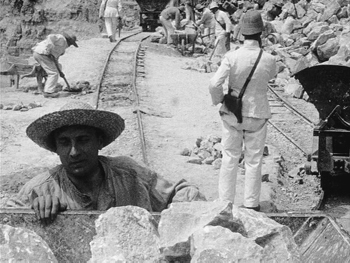

There are some brilliant moments of staging in depth. After Julien is sentenced to twenty years of hard labor, his new situation is introduced via a tracking shot with the camera atop a cartload of stone which he is pushing. Gradually the laborers breaking stone and the guards overseeing them are revealed (below left). In another shot in the ruins where Corradin is tailing Rudeberg, he is glimpsed in the background (below right).

In a scene late in the film, Julien plans to flee with Régine and their daughter Christiane. He is dressed as their chauffeur, but Corradin shows up and spots the car. Julien hides and watches him from behind a tree in the foreground.

We then see the two women approaching, framed through the back window of the car and watched by Corradin, in the foreground. He ducks down and pretends to fiddle with the car’s engine to prevent their realizing who he is as they draw near.

I could go on illustrating such stylistic flourishes, but I leave it to you to find them for yourself. There’s a very early example of a montage sequence to compress the passing of World War I into a series of titles, from 1914 to 1919, superimposed over stock footage of combat, and a marvelously choreographed high-angle scene in a forest as a troop of policemen pop out of nowhere to surround and arrest Julien.

All serials need stunts

Much of the film consists of conversations and confrontations among the characters, a trait which no doubt led critics to contrast the more action-oriented serials of recent years. Still, there are two sequences where derring-do takes over. After the police arrest Julien, he makes an escape via a rope down the tower and wall of his chateau, a feat accomplished in a single take tilting down to follow his progress.

Later, in an episode entitled “The Human Bridge,” Julien and four of his fellow prisoners escape from their guards while working on a railroad track. This lengthy sequence involves first the commandeering of a passing train and then a chase over an area of rocky crags. At once point the escapees find the rickety remains of a tall bridge above a river gorge and fling ropes across. The four other prisoners then lie end to end, clinging to the ropes, forming a bridge to allow Julien, who has been wounded during their flight, to cross over. One extreme long shot of the scene shows two of the men’s hats falling off, demonstrating as they drift down to the bottom that there is no trick photography involved. It is certainly as impressive as any of the stunts in Feuillade’s films.

Touches of Impressionism

La Maison du mystère certainly cannot be characterized as an Impressionist film. Yet the movement was beginning to expand in 1921, and there are some moments of subjectivity that draw upon its newly minted conventions. As his trial is drawing to an end, Julien closes his eyes, and the shot goes out of focus. We see a series of quickshots of his surroundings and his family as he seemingly recalls the events of the trial as a montage scene. Finally the same framing of Julien shows him coming into focus.

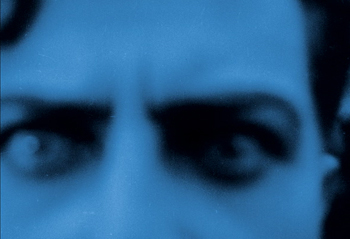

This is a fairly straightforward Impressionist device, but a more daring suggestion of a subjective state occurs much later. Julien’s daughter Christiane and Rudeberg’s son Pascal have fallen in love, and they vow that if they cannot marry each other, they will both commit suicide. When the villainous Corradin forces Christiane to agree to marry him, Pascal sets out to drown himself. His distraught state of mind is conveyed in a single shot as he walks toward the mill pond and hesitates. As he moves into the shot, he is framed in a standard medium close-up. As he hesitates, however, he moves unusually close to the camera and then backs partway out of the frame, as if afraid to continue. Finally he turns and stares into the camera, moving forward out of focus until his dark-shadowed eyes fill the frame. The implication is that he determines to go on with his plan.

(Fans of Evgeni Bauer will recognize Vladimir Strizhevski, the son in the director’s final film, The Revolutionary.)

Star turn

Apart from the imaginative staging, cinematography, and design, La Maison du mystère is full of fine performances. It provides a vehicle for a virtuoso performance by Mosjoukine. He is part Douglas Fairbanks, part Lon Chaney as he leaps energetically about in the early parts of the film and then dons various disguises during his long period as a fugitive. He briefly poses as a clown in a small circus and later returns to work incognito in his own factory as a wounded war veteran with a limp and eye-patch.

Mosjoukine’s fellow actors refuse to be overshadowed by the star, with Hélène Darly as Régine managing somehow to age from a young lady to a mature mother without any apparent change of makeup. Nicolas Koline, best known as Tritan Fleuri in Napoléon vu par Abel Gance, brings something of his usual comic persona to Rudeberg, while also conveying the character’s guilt over choosing to use his photographs for blackmail purposes rather than to reveal Julien’s innocence. Charles Vanel, who had been acting in films since 1910 and would become a major star in the sound era, conveys Corradin’s villainy perhaps too well, making one wonder why any of the other characters ever trusted him.

Flicker Alley, along with the Cinémathèque française, David Shepard, and Lobster Films, have filled in a major gap in film history, and we are indeed doubly grateful.

The quotation from Louis Delluc and information on the production of the film come from the essay, “The Art Film as Serial” by Lenny Borger with David Robinson, included as a booklet in the DVD set.

Impressionist films have been included in some of our “best films” of ninety years ago series. See 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.