Archive for August 2015

Dead man talking

Confidence (2003).

DB here:

“So I’m dead.”

At the start of Confidence we hear Jake Vig’s voice as we see him lying bloodied on a pavement. As the protagonist of a neo-noir, Jake recalls the classic start of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). There Joe Gillis (an echo of gigolo?), floating face-down in a swimming pool, begins to recount his stay as a kept man of faded film star Norma Desmond. That opening has become a touchstone for the grim fatalism of film noir, as well as a mark of daring screenwriting. The guy telling the story is dead! How cool is that?

Anybody interested in how films tell stories has to be interested in narrators, those figures—either mere voices or tangible characters—who recount, recall, or replay the story action. And anybody interested in Hollywood film knows that such narrators are hallmarks of a giddy period of cinematic innovation, as recognizably “1940s” as flashbacks, moody subjective sequences, and twisty plots. In that era we find narrators well outside that terrain known as noir. Romantic dramas, family sagas, comedies, Gothics, musicals, and other genres made ample use of voice-over commentary, and it didn’t always suggest a doom-laden atmosphere.

Still, dead narrators seem to be pushing things. They flout realism (How can a dead person tell anything?) and they raise problems of logic (To whom is this person speaking?). Is it a chatty corpse (Wilder originally wanted a morgue opening introducing Gillis) or an ethereal spirit divorced from the dead body?

Dead narrators turn up surprisingly often in the 1940s. During this period, as I’ve argued on this site and in the book I’m working on, many storytelling techniques we take for granted coalesced. There emerged a rough menu for handling them, and ambitious filmmakers played with several possibilities. That play didn’t stop in the Forties; we still have new versions of flashbacks, subjectivity, and the like. So let’s look at posthumous narrators in the Forties, with some glances at a trio of more recent efforts.

As a non-dead and highly reliable narrator, I must warn you of spoilers ahead.

Guiding spirits

The Human Comedy (1943).

Most simply, posthumous narration can be motivated as letters (Letter from an Unknown Woman) or diary entries (Thatcher’s journal in Citizen Kane). Similarly, Heaven Can Wait (1943) gives us a dead man explaining episodes from his life to an inquisitive official in the afterlife. The more flagrant cases, however, involve dead narrators who recount the entire film we see in voice-over, as in our prototype Sunset Boulevard. Knowing that the protagonist is dead at the start shifts our attention to how he or she will die.

Posthumous narrators go back a fair bit. In literature, Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) presents the ruminations of the town dead, in the manner of the cemetery climax of Our Town (1938 play, 1940 film). Wilfred Owen’s poetic monologue “Strange Meeting” (1918) presents soldiers reuniting in Hell, ending with the poignant line, “Let us sleep now….” Addie Bundren, the dead mother of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930), narrates portions of the novel from her coffin. In a pulpish pastiche of Faulkner, Kenneth Fearing’s mystery novel Dagger of the Mind (1941) includes a chapter narrated by a man who’s been murdered. Radio drama also included voices from the beyond. Examples include “Ghost Ship” (1940), with a victim recounting his own murder, and Norman Corwin’s “Untitled” (1944), which reveals the narrator to be a dead soldier.

In film, World War II brings forth the prospect of dead servicemen returning to tell their tales. “I am Matthew Macauley,” says a face superimposed over imagery of radiant clouds. “I have been dead for two years. But so much of me is still living that I know now that the end is only the beginning.” This is indeed a beginning, of The Human Comedy (1943). Having died in the war, Matthew will guide us back to his hometown and his household’s daily routines.

Matthew’s voice-over goes on to introduce his family members, including son Marcus on duty in the army. After a scene in which a spectral Matthew joins his wife at her work, his voice discreetly retires. It recurs only twice before he and his now-dead soldier son faintly enter to watch the family welcome their new member, Marcus’s pal Toby.

“You see, Marcus, the ending is only the beginning.” Matthew’s address to us has become piece of fatherly advice.

The dead narrator of The Human Comedy never intervenes in the action on earth, but an all-seeing intelligence exercises more authority in The Seventh Cross (1944). Seven prisoners escape from a concentration camp, and Ernst Wallau’s narration launches the film. During the escape sequence he rapidly introduces each of his comrades.

Fairly soon all but one are captured and executed on crosses planted in the prison yard. The first man to be crucified is Wallau, our narrator. After he is killed, his voice-over continues: “I was dead. I could see.”

Wallau’s commentary chiefly follows his friend George Heisler, who manages to elude the Gestapo while the other escapees are found and killed. Wallau’s narration continues through the film, chronicling not only the fates of the other men but probing Heisler’s state of mind. Wallau tells us what Heisler is thinking, guides us into his memory, notes things that Heisler has forgotten, and even informs us what other characters will do in the future. Confronted with this numb, almost mute character, we need the continual commentary of Wallau to give access to his inner life.

Wallau is that rare voice-over narrator who flaunts his omniscience. Being dead, he has total access to our world and can witness anything happening there. Despite Wallau’s godlike power, in good Hollywood tradition his narration attaches itself chiefly to Heisler. But here that restriction reflects simply Wallau’s foreknowledge, signaled at the start, that only Heisler will survive. The question becomes: How?

The answer comes through Wallau’s goading Heisler to find faith in others. At the start, Heisler is close to despair, and his flight stems from sheer instinctual survival. At the film’s midpoint, all his comrades have been killed, and Wallau’s long-term escape plan has failed. Heisler can’t any longer mechanically follow his mentor’s instructions. He must forge a new goal, seize the initiative, and learn to trust people. He must learn what Wallau told him from the start: there remain traces of humanity in Germany.

As Heisler’s hopes grow and his network of allies expands, Wallau’s prodding voice-over subsides. It reappears near the end, at the moment Heisler realizes how much he owes others. Heisler speaks of his debts, and Wallau murmurs in antiphony the names of those who have helped him, including some Heisler has never met.

Now that Heisler has joined the struggle with full commitment, Wallau can vanish. “Goodbye, George Heisler. I can leave you now.”

Ghostly narrators like Wallau and Matthew Macauley call to mind the nosy angels and spooks of so many 40s films. Those have their counterparts in radio dramas like “Good Ghost” (1948) and the parodic mystery novel Dead to the World (1947), with a dead detective narrating his efforts to solve a case.

As usual, a lot depends on timing of information. If we learn that the narrator is dead at the start, as in the films just mentioned and in Scared to Death (1947), a certain amount of the action can seem foreordained. Alternatively, there can be a surprise. Radio plays, it seems, tended to reveal their dead narrators as a twist ending. With less fanfare, a film can simply seem to forget the opening commentary. The Gangster (1947) is initially narrated, without a frame situation, by the crooked protagonist. As a result, we expect him to survive. Yet he dies in the course of the action. The filmmakers faced a problem: To return to the narration at the end or not? To revive his voice-over might suggest that he endures in some supernatural realm. Instead, an impersonal external voice takes over to balance the opening.

With the convention of the dead narrator in place, a film could flirt with the possibility that the initial voice we hear has no living source. The opening credits of Woman in Hiding (1950) strongly suggest that a betrayed wife, racing down a hillside at night before crashing over an embankment into a river, has been killed. Her commentary rises up during a scene of the police dragging the river, and she seems to be mocking her husband from beyond the grave.

Is this a female variant of Joe Gillis’ voice-over? Watch the whole movie to find out.

In the same year as Woman in Hiding, Sunset Boulevard gave us another voice from the Beyond. If the film’s technique seems less original coming after a string of dead narrators, at least it can be credited with making the narrator the protagonist (unlike The Human Comedy and The Seventh Cross) and for using the device in a full-blown A picture (unlike Scared to Death and The Gangster).

In sum, the dead-narrator technique became a schema, a pattern which filmmakers could simply copy, as in Scared to Death, or tweak, as in the apparently dead narrator of Woman in Hiding. Wilder offered his own variant on the schema. We tend to remember his as the prime example, maybe even as the first one. But it often happens in the 1940s that the originality of a noteworthy film stems from a revision of a schema that was already in circulation, not only in film but in other media.

The weekend Laura died

Occasionally, the variety of options at the period sets up more dissonant relations. Laura (1944) is probably the most famous example.

Vera Caspary’s original book is divided principally into first-person blocks recounted by bon vivant Waldo Lydecker, detective Mark McPherson, and magazine editor Laura Hunt. Early versions of the screenplay attempted to capture multiple-viewpoint narration through flashbacks and voice-overs. What happened to this structure, however, reveals a process we’ll encounter elsewhere: fiddling with the film in post-production yielded some startling, perhaps unintended novelties.

Laura Hunt has apparently been murdered by a shotgun blast to the face. When the film starts, McPherson is calling on her mentor Waldo Lydecker, an effete columnist and radio commentator. McPherson lets Waldo accompany him on his inquiries before the two retire for a dinner at the restaurant Laura loved. There, via flashbacks and voice-overs, Lydecker recounts Laura’s rise to prominence. (In a scene cut from the final film, there’s an indication that Waldo’s tale is partly false—an early instance of a lying flashback.) The other characters’ flashbacks and voice-overs were abandoned in production, so the rest of the film is rendered objectively.

We later learn that the original victim was not Laura, which makes Laura either a new suspect or a target for the killer’s second try. At the climax, it’s revealed that Waldo is the culprit; he concealed the gun in an antique clock that he had given Laura. While his pre-recorded program is broadcast, he returns to her apartment and tries to kill her. Laura eludes him and as he wildly fires his gun, he is shot by McPherson’s team.

What makes the finale curious is the film’s framing device. The first scene starts with Waldo’s voice-over: “I shall never forget the weekend Laura died.”

This appears to cast the entire film as a flashback, starting with McPherson’s visit to Waldo. Within that flashback to the weekend, we have further flashbacks–that is, Waldo’s dinner-table explanations to McPherson. Such Russian-doll embedding is found elsewhere during the 1940s. At the end of the evening, when Waldo leaves, the camera lingers on McPherson and we become attached to him for nearly all that follows.

In screenplay drafts, this last shot would have initiated Mark’s voice-over narration, which would constitute a chunk parallel to Waldo’s. This is further evidence that Waldo’s string of flashbacks, including his opening voice-over, functions to write finis to “his” section of the film. But in the finished film, without McPherson’s voice-over block, Waldo’s initial voice-over hangs there, apparently framing the whole film. It would have been easy simply to cut that commentary and retain the opening camera movement revealing McPherson browsing among Waldo’s treasures, perhaps with some more nondiegetic music. Then Waldo’s offscreen admonition would bring in his voice for the first time. After this, Waldo’s later flashbacks and his voice-over narration would become neatly nested and perfectly conventional.

Clearly, decision-makers wanted to retain Waldo’s ripe commentary to open the film; it has expository value, and it introduces a very intriguing character. But we don’t hear that enveloping voice again, so for the rest of the film we might take Waldo’s remarks as akin to those that open Rebecca (1940) or Flamingo Road (1949). In these films and many others, a reminiscing character voice introduces the story action from an unspecified point in time and space. And the plot’s shift to McPherson’s activities seems to suggest that the whole opening stretch, including Waldo’s initial recounting, should be taken as a unit, “his” section of the film. So when Waldo is shot down and starts to die, we might have a situation like that of The Gangster, where the narrator is killed in the course of the action he introduced, and the film forgets what started it all.

Instead, Laura takes the option that The Gangster avoided: it brings back the dead man’s voice. After Waldo collapses, there’s a cut to McPherson and Laura leaving the frame. As the camera moves in on the shattered clock face, we hear, “Goodbye, Laura. Goodbye, my love.”

The line might be taken as Waldo’s dying words spoken offscreen, except that the line is miked far more closely than his speech earlier in the scene, when he’s actually closer to he camera. In its acoustic texture, this unsituated sign-off formally balances the unsituated opening. But it also raises the possibility that the dead Waldo has launched the whole story and now bids Laura farewell from that realm wherein defunct narrators dwell.

The opening does hint that something otherworldly is going on. A tart, suave voice wells up from sheer darkness, perhaps a noir equivalent to the sunny eternity from which Matthew Macauley speaks in The Human Comedy. Yet for a dead narrator, Waldo is either ill-informed or misleading. He speaks of “the weekend Laura died.” But if he lived through the events of the film, he knows that she did not die. Of course, his fib helps the film mislead us; the first half presupposes that Laura was the victim. If we remember that an unused scene was going to reveal that his flashback tales to McPherson contained lies, we may conclude that Waldo is as unreliable in death as he was in life.

Some of these inconsistencies apparently spring from late decisions in production. The original ending, as scripted and shot, lets Waldo survive. As he’s led off, he says, “Thank you for everything, my dear. . . You’re all I’ll be thinking of—till Time stands still—for me. Goodbye, Laura.” The speech is heard offscreen as the camera pans and holds on the clock.

Fox production head Darryl F. Zanuck was dissatisfied with many aspects of this conclusion and so a new version was filmed. In that version, Waldo is shot and dying. We see him speak the same lines, and only then does the camera pan to the clock. The release version, with Waldo’s simpler, closely miked farewell over the shot of the clock, was evidently decided on still later.

For what it’s worth, both the original shooting script and the revision distinguish between lines marked as “WALDO (narrating)” and “WALDO’s voice” for offscreen delivery. In neither version are Waldo’s dying lines marked as “narrating.” And in neither do we get an indication of the final camera movement that lets Laura and McPherson leave the shot in order to target the shattered clock face. Yet we do have a sonic texture in the last lines that is closer to a narrator’s voice.

In sum, while presenting a haunting conclusion—the clock was Waldo’s gift to Laura, and the shattered face recalls his first victim—the soundtrack firmly reminds us of the opening. Do we have a dead narrator? Some cues are there, but they’re sketchier than those in other films of the era. (For one thing, in those films, the narrator tells us he or she is dead.)

The unexplained return of Waldo’s voice, now gentle, has a surprising poignancy. Because of its loose ends, the final moments become more evocative, and more poetically enticing, than the tidy, explicit wrapup of Sunset Boulevard. In such ways, Laura’s final moments provide an eccentric revision of the dead-narrator schema. The result may have encouraged filmmakers who followed to risk inconsistency for the sake of powerful immediate effects.

In an earlier entry, I traced how studio pressures made the narration of Preston Sturges’ The Great Moment oddly off-balance. Evidently something like this happened with Laura. In the pressure to get a film finished and out the door, to retain striking bits that may ultimately not make sense when put together, Hollywood filmmakers can innovate by accident.

Dead men tell no tales

Auto Focus (2002).

Once the dead-narrator schema was available, Forties filmmakers were able to tweak it in various ways. And the changes didn’t end then. To see how the same process of schema and revision has continued, consider three much more recent examples.

Paul Schrader’s Auto Focus is a straightforward case. Bob Crane’s voice-over appears early in the film, though not at the very start, and recurs six times before the final scene. The brief comments punctuate Crane’s career decline and his descent into sex addiction. As happens with The Seventh Cross and other films using voice-over narrators, the second half employs the device less intensively than does the first. It’s as if in a film’s Development section we’re expected to be absorbed enough in the action not to need explanation, and we’re sufficiently primed to know what the important issues are.

When Crane’s head is bashed in by his companion in sexual buccaneering, we have a case comparable to The Gangster: the narrator doesn’t survive. Crane’s voice has been silent for 28 minutes, so we might assume that we’ve lost his voice-over. But it returns over his bloody body, recounting in an offhand way the aftermath of his death. His voice remains as perky as it has been early in the film, in both his commentary and his explanations to his wives. “I’m a normal guy,” he has insisted, and his bland wrapup shows him insouciantly unaware of the implications of living and dying as he did. He can’t condemn his killer. “He was a cool guy in his way. . . . Men gotta have fun.”

Martin Scorsese’s Casino (1995) reworks the dead-narrator schema in more complicated ways, in the process borrowing other 40s conventions. During that period, multiple-narrator films became quite common. Again we have a prototype—Citizen Kane (1941)—but again it wasn’t alone. Trial films featuring flashbacks that dramatize testimony had become fairly common in the 1930s, and a couple of detective films (e.g., Affairs of a Gentleman, 1934; Thru Different Eyes, 1942) used flashbacks to present different witnesses’ versions of events. It would become a staple of crime films like The Killers (1946). Julien Duvivier’s Lydia (1941) transposed the multiple-narrator technique to the melodrama, while The Affairs of Susan (1945) applied it to romantic comedy. Mankiewicz, who seems quite obsessed with the strategy, deployed it in A Letter to Three Wives (1949), All about Eve (1950), and The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

A less common 1940s convention is the replay—the passage that repeats a scene, usually in flashback and usually including information not shown in the first pass. The most famous example is Mildred Pierce (1945), which I’ve fretted at for years (in this entry and this video). We can find less crucial replays in, again, Kane (Susan’s opera debut) and in more obscure films like Beyond Glory (1948).

Casino draws on the replay and the multiple-narrator format and blends them with the dead-narrator one. The film innovates in a couple of striking ways. First, in 1940s multiple-narrator films, the individual narrations are presented in blocks; a solid chunk from one voice, another from another. True, we see some leakage in All about Eve, but basically the narrators’ tales are kept distinct. Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi’s script for Casino hops between two principal narrators, Ace Rothstein (Robert de Niro) and Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci).

Ace and Nicky’s voice-overs are mostly very brief, tagging a cascade of episodes tracing each man’s rise in Vegas, with equally fleeting flashbacks to their origins. The first twenty minutes toggles ten times between the two men’s clipped commentaries. This stretch constitutes a sort of training session, preparing us for the rapid switches in viewpoint that will dominate the film. Again, though, the voice-overs will subside for stretches in the middle, when the scenes become more fully developed. As a momentary, almost twitchy variant we get one extra voice-over—that of a go-between who, in a freeze frame, decides not to tell the mob boss about Nicky’s betrayal of Ace. Significantly, the film’s third major character, Ginger McKenna (Sharon Stone), is allotted no voice-overs.

So Scorsese and Pileggi have fractured the 1940s voice-over schema. But the to-and-fro commentaries I’ve mentioned come after an opening sequence that seems to announce that one of these wise guys is already dead. The first scene shows Ace being blasted out of his car by a bomb. A sprawling body, as if ejected from the explosion, floats through the opening credits. And Ace’s next voice-over launches the film’s cascade of flashbacks by saying they come from the period “before I got myself blown up.” We seem to be in the full-fledged presence of a dead narrator.

We are, but it’s not Ace. At the film’s climax, it will be Nicky who dies at the hands of his own crew. In replays of the car explosion, it’s revealed that Ace actually survived the blast. By 1995 Scorsese and Pileggi could revise the 1940s schema by splitting the narrators and misdirecting our expectations: the apparently living narrator is the one who will die.

What, finally, of Confidence? Jake’s admission that he’s dead fits snugly into the tradition we’re considering, especially since it’s a voice-over initiating a flashback. That flashback takes us to the moments before his execution at the hand of the triggerman Travis.

In those moments Jake explains how his team of grifters accidentally took money belonging to a gang boss and how they proposed to repay him with an even bigger con job. That central story action, itself peppered with backstory exposition, is interrupted by returns to the opening execution situation. Jake’s first voice-over, apparently addressed to us, is differentiated by sonic texture from his explanations to Travis, but when his voice leads us to the past, it has the same degree of auditory presence. In effect, it’s the same confusion of narrating levels that’s promoted in the first long stretch of Laura.

At the climax of Confidence, we see Jake shot not by Travis but by the moll Lily. Travis flees, and so does she. Now we’re back to the opening situation, and a replay of Jake’s opening line, “So, I’m dead.” He seems to sign off. But now more flashbacks reveal that Jake and Lily have staged her gunplay and that the whole scheme has been a very long con. The team reunites and goes off with their millions. Confidence has appealed to our knowledge of the dead-narrator convention to fake us out: the story action won’t end with his death because he’s stage-managed it.

Jake lied about being dead. But so did Ace when he referred to being “blown up.” So did Waldo, maybe. And so do those films that don’t signal that the protagonist has fallen into a dream or a reverie. Actually, narratives are incorrigibly deceptive and full of secrets. You can’t even trust dead guys.

As ever, we’re reminded that modern filmmakers inherit a vast tradition of narrative schemas. Those can be reiterated or revised in unpredictable ways. The tradition is kept alive and engaging, as long as novelty is balanced with familiarity, innovation with redundancy. (Let the narrators explain, throw in some replays,) The way Hollywoood tells it is always indebted to the ways Hollywood told it.

For more examples of dead narrators see the Wikipedia entry and TV Tropes. Long as they are, these lists tilt heavily toward contemporary examples, where posthumous narration seems very common. One reason I posted this entry was to acknowledge older instances of this convention.

Ray Collins was a well-known radio voice as well as a Welles Mercury player. As both Matthew Macauley and Wallau, he seems to have been the go-to man for reliable supernatural voice-over. He had a long Hollywood career, but most baby boomers remember him best as Lieutenant Tragg in the Perry Mason TV show.

I’m indebted to Neil Verma for information about the posthumous narrator in radio plays. Neil also mentions “The Hitch-Hiker” (1942), and these episodes of Quiet, Please: “Inquest” (1947), “In Memory of Bernadine” (1947), “Anonymous” (1948), and “I Always Marry Juliet” (1948). (Listen to any of these here.) Filmgoers probably encountered more dead narrators on radio than on film. Neil’s book, Theater of the Mind, is an excellent account of 1930s and 1940s radio narrative.

The shooting script of Laura is available here. The revised ending is included as well. See also the detailed comparison of the two endings by Despina Veneti at Preminger Noir. The first analysis of the different versions was, I believe, carried out by Jacques Lourcelles in “Laura: Scénario d’un scenario,” L’Avant-scène du cinéma no 211/212 (July-September 1978), 5-11. This publication includes a French-language transcript of the film as we have it, along with cut portions. A detailed account of Laura’s production is provided by Chris Fujiwara in The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger (Faber and Faber, 2008), pp. 36-48. I’m grateful to Jeff Smith for his advice about the sonic texture of Waldo’s voice-over.

The narrational issues raised by Laura go beyond the deceased Waldo’s voice. In the film’s most famous scene, McPherson is becoming obsessed with the dead Laura and, after drinking heavily, he falls asleep in her apartment. The camera tracks slowly in on him as he drops off. There’s the noise of a door from offscreen, and Laura walks in. McPherson is astonished. Laura, released the same week as The Woman in the Window, might seem to be hinting that Laura has been revived in McPherson’s dream.

Kristin has traced the numerous dialogue motifs that reinforce this possibility. Yet most films of the 1940s mark a dream sequence very explicitly (e.g., wavy superimposed lines, dissonant music) or at the least with a dissolve and a close-up or track-in reinforcing the shift to subjectivity. Laura provides only two cues, the sleeping character and the track-in. But as Kristin indicates, these and other factors keep the dream option a possibility for a first-time viewer. See “Closure within a Dream? Point of View in Laura,” Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988), 162-194. Kristin’s essay also offers a comprehensive discussion of the shifts in Waldo’s narration.

The presence of dead narrators would seem to pose a problem for those scholars who believe that in a movie every narrator must have a narratee on the same logical level. For these theorists, film narrators are part of a symmetrical system of communication among personified entities. Those entities are either embodied in the text (McPherson is Waldo’s narratee in the restaurant) or implicit in the very logic of narrative itself. No narrator without a narratee! According to this line of argument, there must be a narratee as dead as Waldo listening to his opening voice-over, but being very, very quiet.

In contrast, I’ve argued that films, and possibly all narratives, are freewheeling and illogical in their use of markers of communication. Films may mimic only parts of a communicative circuit in order to achieve specific effects. In provoking experiences in readers, films seem to me to rely on psychology, not ontology. I float this argument in this chapter of Poetics of Cinema. See also this blog entry.

Earlier entries have touches on the schema-and-revision dynamic of style and story in Hollywood. See for examples my discussion of 1913 films, a consideration of 1940s style, some remarks on walk and talk, a piece on high-school lipdubs, a discussion of replays, and the entry on Gone Girl. Searching “schema” will bring up more. A roundup of entries on peculiar 1940s narratives is here. I analyze narration in All about Eve here. For more on the debt of modern film to 1940s innovations, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Casino.

How he (mostly) got away with it: Matthew H. Bernstein on Preston Sturges

DB here:

Matthew H. Bernstein is a long-time friend and a superb scholar. His biography of Walter Wanger has become a classic of Hollywood business history, and his many books and articles have refined our sense of American cinema. When we learned of his research into Sturges (a favorite of this blog), we were happy to propose that he do a guest entry. Here’s the lively, trailblazing result.

How should films portray sex and marriage? Hollywood’s Production Code, established in 1930, set forth some definite ideas.

Sex

The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing. . . .

Scenes of Passion

They should not be introduced when not essential to the plot.

Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown . . .

Seduction or Rape

They should never be more than suggested, and only when essential for the plot, and even then never shown by explicit method.

They are never the proper subject for comedy.

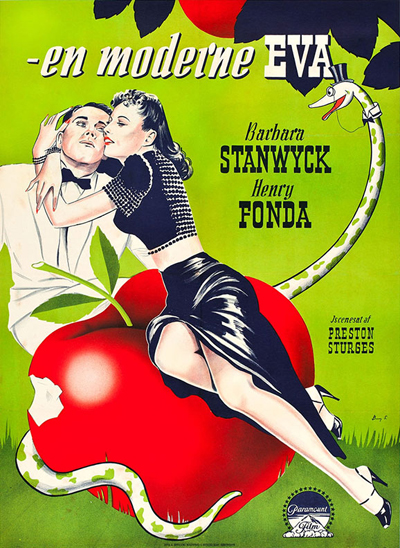

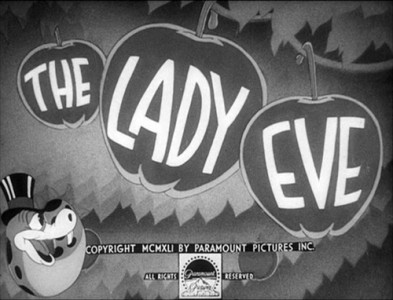

Those of us who savor Preston Sturges’s great romantic comedies of the 1940s—The Lady Eve (1940), The Palm Beach Story (1942) and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944)—admire them in part for their violation of just about all these tenets. They are full of “suggestive postures” like the lengthy chaise longue scene in The Lady Eve. Their central topic is often the seduction of men by women (The Lady Eve, The Palm Beach Story and arguably Miracle). References to extra-marital sex, contemplated or accomplished, abound. And all three films ridicule “the sanctity of the institution of marriage” into the ground. Film critic Elliot Rubinstein once observed, “If Sturges’s scenarios don’t quite invade the province of the flatly censorable, they surely assault the border outposts, and some of the lines escalate the assault into bombardment.”

The Production Code Administration, on paper and in practice, was particularly obsessed with regulating the depiction of female sexuality on screen. Yet Sturges’ attacks on conventional morality are launched by heroines: con artist/card sharp Jean/Eve (Barbara Stanwyck) in The Lady Eve, the hard-headed Gerry Jeffers (Claudette Colbert) in The Palm Beach Story and the naïve man-bait Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. They are all variants of what Kathleen Rowe has called the “unruly woman,” characters who create “disorder by dominating, or trying to dominate, men,” and being “unable or unwilling” to stay in a woman’s traditional place. Mary Astor’s much-married Princess Centimilia/Maude in The Palm Beach Story deserves an honorable mention here too.

True, by each film’s conclusion, the Sturges heroine agrees to get or stay married. She fulfills the conventions of romantic comedy and the stipulations of the PCA. Yet in each film the path to a proper end looks so much like a roller-coaster ride that the significance and sanctity of marriage come to seem ridiculous.

How did Sturges get away with so much? A look behind the scenes at the negotiations around The Lady Eve can help us understand his strategies. It also shows that the Code was more flexible and fallible than we often realize.

Convolutions in the Code

Sturges had one advantage at the outset. He worked in a genre that was already testing the limits of the Code. Granted, the PCA in 1934 aimed to regulate film content in every genre. None, however, flaunted, even parodied, the strictures of the Code more thoroughly than screwball comedy did. Rubinstein puts it well: “The very style of screwball, the complexity and inventiveness and wit of its detours around certain facts of certain lives, the force of its attack on the very pieties it is pledged to sustain, cannot be explained without recognition of the censors. Screwball comedy is censored comedy.“

By the end of the 1930s, filmmakers were pushing hard against censorship. Romantic comedies were growing more risqué by the month, as shown by 1940 releases like My Little Chickadee, The Philadelphia Story, The Road to Singapore, Too Many Husbands, The Primrose Path, Strange Cargo, and most especially, This Thing Called Love. A sort of arms race took place, and Sturges, emerging as a writer-director in 1940, benefited from this escalation.

Just as important is a fact that many fans of Hollywood still don’t realize. We like to think that daring filmmakers were charging boldly against an iron wall, with chief censor Joseph Breen and his associates setting forth implacable demands. But the administration of the Code was not a mechanical, totalitarian affair. It was most often a matter of negotiation.

Releasing Hollywood’s product, even risqué films, benefited all parties involved. If the Code were enforced with absolute rigidity, the industry would suffer. Some films would have to be abandoned. Then urban audiences would have found the safely released product pallid, and critics would have complained about bland output. Then as now, edginess sold, and at least some audiences were eager for it.

Accordingly, Breen and co. recognized that the Code could not be applied ruthlessly. Indeed, historians Lea Jacobs, Richard Maltby and Ruth Vasey have shown that the PCA, like its forerunner the Studio Relations Committee, often helped filmmakers find ways around the most stringent policy demands. Through a give-and-take, censors and filmmakers could settle on scenes and lines of dialogue that could avoid public outcry. No one flaunted and taunted the PCA as well as Sturges, yet Breen and co. often helped him find ways of rendering suggestive situations without baldly transgressing the Code.

One typical filmmaker/PCA tactic that favored Sturges was an appeal to ambiguity. Far from being inflexible, the staff recognized that not every viewer picked up on a lewd line or suggestive situation. Some viewers would find no innuendo in a sexually-charged scene. (The 1940s critic Parker Tyler referred to this as “the Morality of the Single Instance.”) For example, in The Lady Eve, there’s a fade-out from Charles’s and Jean’s passionate embrace in the bow of the ship at night to the fade in of the ship’s prow slicing through the ocean the next morning.

That passage would suggest to the naïve viewer that they kissed for a while and went to their cabins separately. After all, in the morning we find Jean getting dressed in her stateroom and talking with her father. Then we see Charles on deck alone, waiting for Jean.

But the sophisticated viewer would understand that the earlier fade-out indicated what Joseph Breen routinely called “a sex affair.” (The ocean spray on the fade-in could be seen as a very subtle extra touch.) Crucially, Jean’s later statement to Hopsy after she is unmasked as a cardsharp sustains both readings. “I’m glad you got the picture this morning instead of last night, if that means anything to you . . . it should.” When self-regulation was well-calibrated—and this was a moment-to- moment, scene-by-sceene, film-by-film achievement—there was wiggle-room that would let innocent viewers remain innocent while letting sophisticated viewers feel sophisticated.

Apart from the increasing eroticism in screwball comedy and the willingness of the PCA to work with filmmakers to allow double layers of meaning, Sturges benefited from good timing. During this period, Breen grew more permissive in his application of the Code. He never explained why, but the late-1930s bombardment of questionable material was probably one cause. Breen was pretty exhausted after seven years of trying to accommodate the filmmakers’ increasingly outré ideas. He was so tired that he temporarily resigned in Spring 1941.

Sturges’ circumvention of the Code also depended on his personal qualities. Clearly he was a persuasive negotiator. The PCA correspondence shows Breen and his successor, Geoffrey Shurlock, rescinding countless directives they initially gave him to eliminate dialogue lines or bits of action. It’s likely that the PCA admired Sturges’ comic gifts and thus gave him greater room to maneuver than other directors enjoyed. (Much the same thing happened when the Studio Relations Committee had given leeway to Ernst Lubitsch prior to 1934.) Sturges also employed a tactic of overkill. In his scripts and in the scenes as finally staged and shot, he created so many potential infractions of the Code that to challenge each one would reduce the film to rubble, or reduce Breen and co. to stress-induced madness.

Still, Sturges played the PCA game. His convoluted plots stuck to the letter of the Code, always finally coming down on the side of pure romance and happy marriage. But they wreaked havoc with its spirit—often with the PCA’s sanction. By the premiere of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Sturges was relentlessly mocking the PCA’s regulations. It’s likely, I think, that the PCA was for the most part in on the joke.

After negotiations, which grew more elaborate with each title, each Sturges romantic comedy received a seal. The films made it through partly because of the PCA’s quixotic mandate, partly because the Code’s requirements had been loosened, and partly because of Sturges’ extraordinary skill in exploiting the Code. These are the crucial reasons Sturges got away with it. Along with his prolific comedic imagination, he was often aided by the very body that was supposed to be censoring him.

Once the Sturges film was released, the PCA staffers could wearily pat themselves on the back for a job well done. Yet critics’ reviews, complaints from state censor boards, and letters of protest from ordinary viewers indicate that the agency often badly misjudged how the films’ moral tone would be received. The PCA’s dual mandate—to try to give filmmakers the maximum freedom to create risqué situations but at the same time to uphold the Code–was a tightrope walk. With Sturges and other filmmakers, the agency lost its balance. Sometimes the PCA didn’t diminish the sexual dimensions enough, and sometimes the agency did not even notice elements that could give offense.

There were signs already, in the reaction to the 1940 burst of sexier films like The Primrose Path and This Thing Called Love. Local informants had asked MPPDA attorney Charles C. Pettijohn, “Doesn’t Mr. Hays have any influence with the producers any more, and has that fellow Breen out there killed himself or has he just been compelled to walk the gangplank?” Unlike the PCA staff, who had worked day by day to tone down an audacious script and had faced the charms of a persuasive filmmaker, local censorship boards reacted solely to a finished Sturges film. They merely saw what was on the screen. Many did not like what they saw.

Up the Amazon for a year

The PCA correspondence concerning The Lady Eve is surprisingly brief. Before the film was completed and a seal was granted, Breen sent only two letters to Luigi Luraschi, Paramount’s liaison on censorship. They strikingly illustrate how cooperative Breen could be when it came to scenes regarding illicit sex.

When he read Sturges’s first complete script of 7 October 1940, Breen had objections to many “questionable lines of dialogue.” Breen warned Sturges and Luraschi against anything “suggestive” in the scene between Muggsy and Lulu as they say their farewells before departing the expedition. In this brief exchange, Mugsy stiffly tells her “So long, Lulu…I’ll send you a post card” as she demurely (looking down) places a lei over his neck. This brief exchange directly undercuts Hopsy’s just-spoken, high-minded farewell to the Professor: “This is the way I’d like to spend all my time…in the company of men like yourselves…in the pursuit of knowledge.”

While it’s difficult to imagine Muggsy as a sexual partner to anyone, the woman’s downcast face and her gift of a lei could be seen to suggest her heartbreak.

Jean’s later, rapid-fire description of Hopsy’s many female admirers in the Main Dining Room of the S.S. Southern Queen originally contained comments about women who were “a little flat in the front” or “a little flat behind. ” These were cut because they were too physiologically specific about the female form. We hardly miss them, as Jean was permitted to deliver plenty of color commentary, as she detailed the women’s futile attempts to attract Hopsy’s attention.

However, Breen wrote the word “in” alongside certain demands he had made for eliminations in his 9 October letter, indicating that Sturges and Luraschi had persuaded him to relent. For example, Breen eventually accepted this exchange from Jean and Charles’s first evening together. Charles has suggested they go dancing:

Jean: Don’t you think we ought to go to bed?

Charles (after a pause): You’re certainly a funny girl for anyone to meet who’s just been up the Amazon for a year.

Jean: (after a pause): Good thing you weren’t up there two years.

Breen’s next letter (21 October) on Sturges’s revised script expressed satisfaction with all the changes made, noting that Jean’s line about heading to bed “will be delivered without any suggestive inference, or reaction.”

In the finished film, there is nothing arch about Stanwyck’s thoughtful, almost parental delivery of the first line, spoken as she looks straight ahead and then looks down to stub out her cigarette before she turns to face Charles. Likewise, her delivery of the second line is wry and mildly mocking yet almost compassionate. Still, the connotation remains that Jean is suggesting they sleep together. Instead, the couple proceeds to Charles’s cabin to meet his snake Emma.

Breen was particularly concerned about other allusive dialogue. At the Pikes’ party, Sir Alfred (Eric Blore) explains to Charles a fictionalized version of Jean’s family history which resulted in the existence of two sisters, one a lady, one a cardsharp. (Sir Alfred will later describe this as “Cecilia or the Coachman’s daughter, a gaslight melodrama.”) Breen insisted that Sir Alfred’s tale include a line indicating that Jean’s mother divorced her elderly earl before taking up with the groom “Handsome Harry” and giving birth to Jean. That way Jean’s birth would not seem illegitimate. Sturges obliged. Yet he somehow persuaded Breen to retain this later portion of the Alfred-Charles exchange, also alluding to an adulterous affair.

Charles: They [Jean and Eve] look exactly alike!

Sir Alfred: We must close our minds to that fact…as it brings up the dreadful and thoroughly unfounded suspicion that we must carry to our tombs, you understand…as it is absolutely untenable…that the coachman, in both instances…need I say more?

Why did Breen let Sturges keep in this suggestion that Handsome Harry was the biological father of both sisters, perhaps as the result of adulterous affairs? It is hard to say. True, the offending line concerns a “suspicion” voiced by Sir Alfred, rather than a fact. But Charles immediately affirms its likelihood: “But he did, I mean, he was, I mean…” before being shushed for the nth time by Sir Alfred. Here again, Breen consented to Sturges’s use of questionable material.

Breen’s greatest objection in his initial letter concerned pp. 70-74 of the first submitted script, which suggested “a sex affair.” “Inasmuch as this is treated without the proper compensating moral values, it is in violation of the Production Code, and will have to be eliminated entirely from your finished picture.”

The offending pages outlined a scene between Charles and Jean set on the deck of Jean’s cabin at the end of their first evening together. Just previously, Jean has caught Charles and her father the Colonel (Charles Coburn) playing double or nothing. Charles would then be called away to receive from the ship’s purser the incriminating photo of Jean, the Colonel and Gerald. Charles would then return to the gaming room table and the dialogue exchange with Jean about all women being adventuresses. Then Charles would ask Jean if they can go down to her cabin. There, Charles lights Jean’s cigarette; he “struggles to say something” but Jean tells him, “Kiss me,” and he obeys. (“He crushes her in his arms” as she “sinks back against the chaise longue.”) The film would then cut to a shot of the rail of Jean’s deck and of “the moonlit water beyond. A lighted cigarette arcs over the rail and down into the water. FADE OUT.”

This version presents Charles sleeping with Jean even though he knows from the purser’s photograph that she’s a cardsharp. As Brian Henderson notes, this arrangement of events would make Charles a cad, far worse than the hypocritical prig that he is in the finished film. Sturges eventually solved the problem by having Charles learn of Jean’s duplicity on the morning of their third day together at sea. But before Sturges made this change, Breen’s October 9 letter directed that Charles could not speak the line about going down to her cabin; that the scene could not play out on Jean’s private deck; and that “it would be better to have the embrace with the couple standing up.” The shot of the cigarette thrown over the railing also “should be omitted, on account of its connotations.”

In response, Sturges watered down the offending scene of passion and relocated it to the bow of the ship, where (in a reworking of a scene he had always envisioned) Charles recites his “I’ve always loved you” speech and they eventually embrace as the scene fades out. This created the PCA-approved ambiguity about what transpired sexually between them.

Here, Sturges’s solution to a problem of plot and characterization went hand in hand with the double-meaning practices of the Production Code. Sturges must have written the passionate private deck scene knowing full well that Breen would demand its elimination or transposition. His immediate agreement to revise it was likely a bargaining ploy to earn Breen’s goodwill to bank against other PCA objections.

When Sturges cut the cabin deck setting and the prone postures of pp. 70-74 from the first submitted script, he also saved a crucial part of Jean and Charles’s penultimate exchange as they enter Jean’s cabin.

Charles: Will you forgive me?

Jean: For what? Oh, you mean…on the boat…the question is, will you forgive me?

Although Breen accurately predicted that this bit of dialogue would “probably be acceptable” if the earlier scene “is cleaned up,” for now, Breen stated that their exchange had to be cut “by reason of its reference to the aforementioned sex affair.” In other words, Breen, not unreasonably, read Jean and Charles’s dialogue as referring only to their sleeping together, rather than to everything that transpired between them on the S.S. Southern Queen, including Jean’s duplicity and Charles’s narrow-mindedness. Forgiveness is of course a key issue in the drama of The Lady Eve.

Hix Nix Sexy Pix

The MPPDA issued its seal on 26 December 1940. Released in mid-March 1941, The Lady Eve passed the censors without cuts in Chicago and the states of Massachusetts, New York and Virginia. However, Kansas, Maryland, Ohio and Pennsylvania were a completely different story.

Some local censors demanded deletions of elements Breen had highlighted. Ohio and other localities objected to Sir Alfred’s dialogue about the fantasy fatherhood of Jean and Eve (“as it is utterly untenable that the coachman in both instances. . . .”). But most of the eliminations concerned elements Breen and his team had not commented upon. Among these were (again for Ohio, initially) Sir Alfred’s summary recap of the tale to Jean the next morning: “So I filled him full of handsome coachmen, elderly Earls, — young wives, and the two little girls who looked exactly alike.”

Other targets were Jean’s wisecracks. When Jean and Charles return from her stateroom after changing her shoes, the Colonel archly comments, “Well, you certainly took long enough to come back in the same outfit.” Jean’s reply–“I’m lucky to have this on. Mr. Pike has been up a river for a year”—offended Pennsylvania. Ohio objected to Jean’s comment, “That’s a new one, isn’t it?”, when Charles invites her into his cabin to see Emma.

Yet another instance concerned Charles’s exchange with Eve during their wedding night train ride. He is asking about her previous marriage to Angus.

Charles: When they brought you back, it was before nightfall, I trust.

Jean: Oh, no.

Charles: You were out all night?

Jean: Oh, my dear, it took them weeks to find us. You see, we’d make up different names at the different inns we stayed at.

Though Jean and Angus were married, the implication of using false names at a hotel (which Sturges would recycle for Trudy and her unknown husband in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek) was the deal-breaker for Ohio. Of course, one possible connotation of Eve’s many pre-Charles couplings is that not all of them were marriages. (If they were, this imaginary Eve is an early version of the Princess in The Palm Beach Story, another figure who satirizes conventional marriage.) Yet Breen’s only comments on this scene concerned Eve’s nightgown and particularly the scene’s blocking—that Eve’s revelations of her previous marriages occur away from the bed and that the bed be deemphasized throughout the scene.

Sturges must have made the case that there was no room to have the actors sit elsewhere. Meanwhile, Breen was distracted from what Jean was saying by where she was when she said it.

Local censors were most keenly opposed to two other scenes that Breen had ignored. Both take place in Jean’s stateroom.

In the first, Charles replaces Jean’s broken shoe. In one twenty-second two-shot, he kneels down to slip the shoe on her foot; looks over her foot and slowly looks up her leg all the way to her face; expresses his hope that he didn’t hurt her when she tripped him in the dining room; and then on his way to looking down at her leg and foot again, pauses momentarily but very definitely, on her décolletage. Then he looks back up at her again. There is no dialogue to distract the viewer from what Charles is looking at.

Oddly, no censors objected to this very suggestive shot; instead they focused on what ensued. Ohio, Kansas, and Maryland joined Pennsylvania in demanding the elimination of what the last described as the “semi close-up view where [Charles] allows his eyes to pass up and down over her.” This was a quick POV series of shots in which (1) Charles struggles to look at Jean; (2) Jean appears blurry and asks Charles if he’s all right; and (3) Charles, after swallowing, struggles to reply in the affirmative.

Charles is so “cockeyed” from Jean’s perfume that when they eventually stand up, he can make only the weakest attempt to kiss her, which Jean easily repulses. To the censors, however, the combination of close shot scale, physical intimacy, and intoxication (even from perfume) was intolerable–too expressive of Charles’ rising desire. I suspect they actually conflated the lengthy take and the medium close-ups (no “looking over” occurs in the point of view sequence). In any case, censors had seldom seen such “looking over” shots since the early 1930s.

In addition, all four offended states were roused by the famous chaise longue scene. As Charles tries to apologize for scaring Jean with his snake Emma, she holds him close, runs her hands through his hair, tickles his ear, and breathes heavily in his face. Taking the key elements of the shoe-replacement business to another level, the erotic hilarity of this scene arises from the complete power of Jean’s spell over Charles and their sheer proximity, in two long takes (one lasting 36 seconds, and then a closer, three-minute and fourteen-second shot). During all this time, Jean won’t let Charles kiss her, but their faces are close together and their lips are never far apart. For some censors, the most provocative elements of the scene resided in the dialogue that begins with Charles’s fall to the ground ands run through his “accompanying indecent action” (Pennsylvania again) of pulling down Jean’s skirt.

Pennsylvania also cut Jean’s sigh of anticipatory orgasmic release after describing her first encounter with her future husband: “And the night will be heavy with perfume and I’ll hear a step behind me and somebody breathing heavily and then – Ohhhhh!”

Ohio originally wanted the entire scene deleted, starting with Jean’s command “Oh, come over here and sit down beside me” through their final exchange:

Jean: Oh, you’d better go to bed, Hopsy. I think I can sleep peacefully now.

Charles (adjusting his bow tie): Well, I wish I could say the same.

Jean: Why, Hopsy!

Industry representatives negotiated with the Ohio and Pennsylvania boards to try to reduce their demands; Pennsylvania was unmoved, but Ohio was persuaded to let all but their final exchange remain in the film. An outraged San Antonio Amusement Inspector articulated the boards’ thinking when she cut what she called the film’s two “prolonged scenes of passion” in Jean’s stateroom. These, she pointed out to Breen, violated Section 2 of the Code, about “suggestive postures and gestures” and seduction being used for comedy. So in San Antonio, as in Pennsylvania and Kansas, viewers missed the bulk of two of the most celebrated comic scenes in American film history.

With The Lady Eve, Breen’s instincts were generally astute. He had advised against Sir Alfred’s sketch of the Handsome Harry plot. He had eliminated the overt sex affair scene in Jean’s cabin. Yet he missed many elements as well. Besides those stateroom scenes cut by state and city censors, there were ostensibly innocent lines. As Charles searched for a new pair of shoes, Jean says, “See anything you like?” and leans back with a bare midriff.

The constantly repeated phrase “been up the Amazon for a year” references Charles’s extended sexual privation and naivete, which make him susceptible to Jean’s wiles. But the phrase can also be taken as evoking female anatomy itself. The neglect of these details resulted from Breen’s increasing tolerance and his equally increasing tiredness. We’re lucky he left them in.

Upping the ante

The negotiations over The Palm Beach Story and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek followed the pattern set by The Lady Eve. The writer-director proposed increasingly outlandish scenarios; Geoffrey Shurlock and Breen again demanded an increasinglyu longer list of changes across a longer series of letters. Sturges alternately made cuts or assured them he could handle the material.

Once more, certain moments wound up offending local censors. For The Palm Beach Story, released in late 1942, only New York and Kansas passed the film without eliminations. Elsewhere, many of the suggestive elements that Shurlock had criticized were cut. One was Gerry’s line—describing how Tom sees her after many years of marriage–as “just something to snuggle up to and keep you warm at night, like a blanket” (Pennsylvania). Another was the first vertebrae-kissing scene in which a very drunk Tom breaks down a very drunk Gerry’s resistance to having sex.

Other deletions concerned details that had escaped Shurlock’s notice: Pennsylvania removed the underlined portion of Gerry’s explanation to Tom, after the Wienie King’s visit and munificence, of “the look” women get from men: “From the time you’re about so big, and wondering why your girl friends’ fathers are getting so arch all of a sudden – nothing wrong – just an overture to the opera that’s coming.” Even after many changes to her dialogue, scenes with Princess Centimilia could have provoked bans or major cuts. After all, she is followed around by her gigolo Toto (Sig Arno) and (in an ironic adherence to the Code’s demands) marries purely to legitimize her sexual impulses. Yet in part because of Mary Astor’s frantic line delivery, her scenes were retained. Overall, relative to its many potential offenses, The Palm Beach Story faced surprisingly minimal objections.

The entire premise of Miracle and the ensuing action mock the notion of marriage’s sanctity from multiple angles. Breen, the American military, and the Legion of Decency examined the film minutely before it was issued a seal, and many changes were made. For this reason, only one state board (Kansas) cut one line of dialogue: Trudy’s comment that “Some sort of fun lasts longer than others.”

Still, there was much to offend audiences and censors in the completed film. For example, the MPPDA and Sturges received numerous letters of complaint linking the film to the growing problem of juvenile delinquency. One viewer in Minneapolis wrote that the film showed it to be “a subject for slapstick and high comedy, especially if the delinquent is unusually fruitful. . . . My boy thought she must have passed the night with 6 soldiers or sailors. . . . In Hollywood I understand you can get away with despoiling young girls and morals don’t exist except for yokels. Do you have to spread that poison?” Given the growing panic over what was seen as a national JD epidemic, Paramount’s delay in distributing Miracle—it was completed in Spring 1943 but released in January 1944—exacerbated the controversy.

Upon reviewing The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, James Agee famously stated that “the Hays office has been either hypnotized …or raped in its sleep.” The same might seem to be true of The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story, but this was manifestly not the case. There were elements that the PCA didn’t catch–suggestive postures and dialogue, scenes of seduction–because Sturges created so many and whisked them by so swiftly. But he got away with it for other reasons as well. The PCA helped steer Sturges to finding ways of modifying the most brazenly unacceptable material. The standards of acceptability were expanding, controversially, and they would continue to do so. Meanwhile, the response of local censor boards and individual audience members provides crucial evidence of how at times the PCA succeeded and at other times it failed to suppress material that might offend. Knowing this history can only deepen our appreciation of what the Sturges comedies achieved.

This entry is a revised version of a portion of an article that appears as “The edge of unacceptability: Preston Sturges and the PCA” in Refocus: The Films of Preston Sturges, editors Jeff Jaeckle and Sarah Kozloff, forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. Primary sources include Sturges’ correspondence and the PCA files housed at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills. The Lady Eve and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek files are available on microfilm in MLA, History of Cinema: Selected Files from the Motion Picture Association of America Production Code Administration Collection (Woodbridge, CT: Primary Source Microfilm, 2006).

I’ve also drawn on these published sources: David Bordwell, “Parker Tyler: A suave and wary guest”; Brian Henderson, Five Screenplays by Preston Sturges (1986); Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Work of Preston Sturges (1994); Lea Jacobs, The Wages of Sin: Censorship and the Fallen Woman Film (1997); Kathleen Rowe, The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genres of Laughter (1995); and Elliot Rubenstein, “The End of Screwball Comedy: The Lady Eve and The Palm Beach Story,” Post Script 1, no. 3 (Spring-Summer 1982), 33-47.

So these two English magicians walk into a library …

Kristin here:

Two magicians shall appear in England.

The first shall fear me; the second shall long to behold me;

The first shall be governed by thieves and murderers; the second shall conspire at his own destruction;

The first shall bury his heart in a dark wood beneath the snow, yet still feel its ache;

The second shall see his dearest possession in his enemy’s hand;

The first shall pass his life alone; he shall be his own gaoler;

The second shall tread lonely roads, the storm above his head, seeking a dark tower upon a high hill . . . (John Uskglass, The Raven King, via Vinculus)

A word of explanation about why I am writing about a television series is in order. I write almost entirely about films (and occasionally literature), but in 2001 I succumbed to the temptation of an invitation from Oxford University. I was to become a visiting professor and deliver a lecture series on “broadcast media.” The closest I could come to talking about broadcast media was a series comparing film and television narrative structure. The lectures were subsequently published as Storytelling in Film and Television (Harvard University Press, 2003).

This book has given me a lingering reputation for knowing something about television, even though I had not researched or published on television since. Within the past year I have declined two invitations of speak at television conferences, one of them a keynote address. But until now my small dip in the television-studies pool has remained an aberration.

I happen to be a devoted fan of Susanna Clarke’s 2004 bestselling tale of two magicians in Regency England, Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell. I also, despite some reservations, much enjoyed the recent BBC/BBC America seven-episode adaptation of it. The DVD/Blu-ray is being released in the USA today, and I herewith offer some comments on the series.

My main objections to the adaptation relate to changes in the relationship between the two main characters. I think the reasons for this particular problem can shed a little light on how mainstream film and television narratives are conceived and sold to the public. I’ll deal with that subject first before pointing to some of the things I admire about the series.

Many SPOILERS for both book and series from this point on.

Hanging it on the Amadeus hook

The opening of Robert Altman’s The Player is famous for its pitch phrases heard through studio office windows, with variants of the familiar, it’s X Title meets Y Title (“It’s Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman.” “Not unlike Ghost meets Manchurian Candidate.”) The scene is funny, but it’s not far from the sort of thing that happens in reality.

According to series director Toby Haynes, speaking of the BBC, “I pitched it in my first meeting as Amadeus meets Lord of the Rings. They really responded to that.”

Clearly The Lord of the Rings has nothing in common with JS&MN apart from being a long fantasy tale, and I assume it was included to evoke the idea of a big, really successful example of that genre.

As for Amadeus, at first glance one might consider the book’s Norrell-Strange dynamic as being similar to that of Salieri and Mozart, but upon closer inspection there is virtually no resemblance. Salieri’s prime motivation is intense, heartrending jealousy of Mozart’s seemingly effortless genius. Norrell comes into conflict with Strange, but he’s not jealous of the other magician. The barrier between them is a profound theoretical disagreement over the type of magic they should be doing, and it tears the pair apart after their initial delight in discovering each other. There’s no easy comparison for that sort of conflict, no X meets Y. But anyone can grasp the idea of jealousy.

Once the Amadeus idea was in place, it seems to have guided the filmmakers, at least Haynes and presumably screenwriter Peter Harness, to turn Norrell into Salieri and Strange into Mozart. The effort was not entirely successful, partly because thoroughly changing them would gut the premises of the novel’s plot. Staying at all faithful to the book, as many of the scenes do to a remarkable extent, meant that the motivations for the two main characters’ actions, particularly Norrell’s, became inconsistent.

The Amadeus idea proved useful in publicizing the series. Haynes, Harness, and actors Eddie Marsan (Mr. Norrell) and Bertie Carvel (Jonathan Strange) were probably instructed to try and mention it during interviews. Haynes referred to the “Amadeus meets Lord of the Rings” idea frequently (e.g., here). It’s a catchy phrase, and reviewers and entertainment reporters dutifully spiced up their writings with it. In the Wall Street Journal, John Anderson commented, “The two are, in fact, like Salieri and Mozart in ‘Amadeus,’ had Salieri been a little more talented and a little less poisonous.” Rolling Stone‘s David Fear refers to Haynes’s formula, and fan blogs picked up on it. Google “Amadeus” and “Norrell” to find many more examples.

Although Marsan frequently invoked the Amadeus idea, when interviewed on the BBC’s The One Show, he mentioned another comparison suggested to him by Clarke when she visited the set: “She said they represent the two sides of the brain. The right side of the brain, Norrell, is the analytical side, he’s like the librarian, but Jonathan Strange is the spontaneous, confident, creative side, and it’s the juxtaposition between the two.”

This seems to me a better image for the title characters’ relationship than the Amadeus one: two halves of the same entity, ideally working together in balance. It’s a pity it wasn’t used, but Clarke didn’t mention it until the series was into principal photography.

Norrell is not Salieri

In Clarke’s book, Norrell is far and away the better magician, at least until fairly late in the plot. He certainly has no reason to be professionally jealous of Strange when he appears on the scene, and he doesn’t seem much to care that Strange is more flamboyant and socially adept.

The series often suggests, however, that Norrell is the inferior magician. The second episode’s opening depicts his ship illusions at the port of Brest during the first Napoleonic war. Seemingly the French are fooled for only the time it takes some officers to row out and investigate them. Norrell’s illusion seems ineffectual, and one might wonder why in the next scene Parliament is so enthusiastically applauding him and promising all sorts of cooperation in exchange for his help. This, I would suggest, is one of several plot holes resulting from the makers’ devotion to the Amadeus model.

In the book, the ship illusion is highly effective. Not only Brest but “Rochefort, Toulon, Marseilles, Genoa, Venice, Flushing, Lorient, Antwerp and a hundred other towns of lesser importance” are blockaded by Norrell’s ships.

Everyone, it seemed, was delighted with what Mr Norrell had done. A large part of the French Navy had been tricked into remaining in its ports for eleven days and during that time the British had been at liberty to sail about the the Bay of Biscay, the English Channel and the German Sea, just as it pleased and a great many things had been accomplished. (p. 108)

This triumph leads to a successful ten-year career. Although Strange is the one who aids Wellington at the front lines using magic, Norrell contributes in other ways. After the victory at Waterloo, “Mr. Norrell had the satisfaction of hearing from everyone that magic–his magic and Mr Strange’s–had been of vital importance in achieving this.” (p. 337) He then goes into the respectable business of dealing with commissions such as flood control for the Admiralty.

The TV series also presents Norrell’s system for protecting England’s southern coast as a failure, never completed and ineffectual where it did exist. Directly after he installs the system, its faults are apparently revealed when a ship goes aground on a shoal near the same beach, a situation solved by Strange with his flashy creation of giant sand horses. In the book, Strange collaborates on the coastal protection project alongside Norrell. It is installed nearly a decade after the “Horse Sands” episode and works very well. Indeed, the Admiralty finds Norrell so useful that he cannot deal with all the projects they propose to him, especially since he refuses to take on students after Strange leaves him.

Thus unlike Salieri, Norrell’s problem is not inferior talent but an inability to excite others about his magic. He is, as Clarke makes clear over and over, boring. An odd trait in a book’s protagonist, or co-protagonist in this case, but one that she manages to make entertaining. The novel describes Norrell’s first visit to Sir Walter Pole and his attempt to explain his feat of having brought the statues of York Minster to life: “Curiously, though Mr Norrell was able to work feats of the most breath-taking wonder, he was only able to describe them in his usual dry manner, so that Sir Walter was left with the impression that the spectacle of half a thousand stone figures in York Cathedral all speaking together had been rather a dull affair and that he had been fortunate in being elsewhere at the time.” (p. 68)

Even at the end of the ten years, Norrell remains clueless about public relations. Late in the book he and Lascelles go to Brighton to check the new coastal protection system:

“It is invisible,” said Lascelles.

“Invisible, yes!” agreed Mr Norrell, eagerly, “But no less efficacious for that! It will protect the cliffs from erosion, people’s houses from storm, livestock from being swept away and it will capsize any enemies of Britain who attempt to land.”

“But could you not have placed beacons at regular intervals to remind people that the magic wall is there? Burning flames hovering mysteriously over the face of the waters? Pillars shaped out of sea-water? Something of that sort?”

“Oh!” said Mr Norrell. “To be sure! I could create the magical illusions you mention. They are not at all difficult to do, but you must understand that they would be purely ornamental. They would not strengthen the magic in any way whatsoever. They would have no practical effect.”

“Their effect,” said Lascelles, severely, “would be to stand as a constant reminder to every onlooker of the works of the great Mr Norrell. They would let the British people know that you are still the Defender of the Nation, eternally vigilant, watching over them while they go about their business. It would be worth ten, twenty articles in the Reviews.”

“Indeed?” said Mr Norrell. He promised that in future he would always bear in mind the necessity of doing magic to excite the public imagination. (p. 688)

The fact that many of Norrell’s commissions are designed to prevent things from happening also means that the public forgets about them. This scene demonstrates well how Clarke manages to generate amusement out of a character who is so intrinsically dull.

The Norrell we see in the first two episodes of the series is fairly similar to the one in the book–naive, petty, anti-social, and arrogant. His first act in both versions is to twit aspiring magician John Segundus about having read his article on magician Martin Pale’s fairy servants and noticed that he had left one out. He then lets it sink in that he himself owns the only copy of the only book that mentions that servant and thus Segundus could not possibly have read about him.

Despite his faults, however, Norrell is frequently amusing, something the series captures well, especially in the opening episodes. He also arouses our pity when he visits Sir Walter Pole to volunteer his help in the war with Napoleon and is summarily dismissed.

Unfortunately, starting with the third episode the makers abruptly change Norrell’s character, making him more devious and villainous. One reviewer commented on this change:

It’s ridiculously difficult to make you feel a sense of loathing for an actor like Eddie Marsan, but Strange and Norrell went a long way in making you feel like that this week. It’s kind of amazing in such a short space of time how the show has managed to make you feel for Norrell’s plight to restore magic to England, to suddenly very much wondering if that was a good idea.

The reviewer hints that the series has accomplished this change well, but the inconsistency of Norrell’s character continues in later episodes. As he also suggests, it is really Marsan’s splendid performance that manages to make all this hang together.

In the book Norrell does some nasty things, though not nearly so many or so bad as what we see him do in the series. In the novel he neither tries to intimidate Lady Pole into silence nor threatens Drawlight with torture to make him go to Venice to find Strange. He does not accompany Strange to see George III, because he is genuinely convinced from the start that magic cannot cure his madness. When he makes Strange’s book disappear, he offers to pay the publisher’s costs for the entire edition. (He also leaves Strange’s own copy untouched.) He does not berate Childermass for being unconscious for four days after taking a bullet for him. Lady Pole does not create a tapestry in an effort to reveal her situation to Arabella, and hence Norrell doesn’t order it stolen. He never threatens to destroy the other magician, as he is shown doing at the end of episode 4.

His primary mistake, in both versions, is that through shame and fear he hides the fact that he had violated his own principles by summoning the gentleman with the thistle-down hair to resurrect Lady Pole. (The fairy is referred to as the gentleman with the thistle-down hair throughout the book and simply as the Gentleman in the series.) Had he found the courage to tell at least Strange the truth, it might have made him less eager to try contacting a fairy to help him with his own magic.

Norrell does none of these things through jealousy.

Strange is not Mozart

Strange is portrayed as the Mozart to Norrell’s Salieri. He does magic spontaneously rather than learning spells out of books. In the scene where he first demonstrates his magic for Norrell, he says, “One has a sensation like music playing at the back of one’s head–one simply knows what the next note will be,” (p. 233) a line changed slightly for the series. The obvious similarity of this statement to Mozart’s effortless ability to write heavenly music probably sparked the initial link in the makers’ minds between JS&MN and Amadeus. It no doubt influenced Harness to portray Strange simply as a natural genius. Yet the book makes it clear that Strange’s moments of inspiration often either turn out wrong or he simply cannot replicate or reverse them.

For example, the “Horse Sands” episode, so crucial for the series’ creation of the idea of Norrell’s inferiority and jealousy, turns out quite differently in the book. Strange’s sand horses do free the ship from the shoal, but “These did not just disappear when their work was done, as Strange had said they would; instead they swam about Spithead for a day and a half, after which they lay down and became sandbanks in new and entirely unexpected places. The masters and pilots of Portsmouth complained to the port-admiral that Strange had permanently altered the channels and shoals in Spithead so that they Navy would now have all the expense and trouble of taking soundings and surveying the anchorage again.” (p. 278)

The feat impresses the Ministers in London, however, leading them to dispatch Strange to Portugal to help with the war. There Strange’s first successful piece of magic, building a road, is managed through a spell derived from one of Norrell’s books. It’s the same sort of respectable task with which Norrell continues his own success. Later, though, Strange performs ancient, black magic to bring to life some Neapolitan corpses to supply vital intelligence information to Wellington. Norrell refuses to bring rotted bodies to life, but Strange tackles decaying, maggot-ridden ones. The series’ scenes of this episode (above) well convey the horror Strange feels after he succeeds. One of the most effective shots in the series is the long view of the troops, including Strange, moving out of the camp toward victory with the burning windmill in which Wellington has had the zombies locked appearing prominently in the composition (see top).

This parallel to Norrell’s raising of Lady Pole is usually not remarked upon, but it suggests that both have compromised their principles in somewhat similar ways to gain respect and aid the war effort.

Undoubtedly more important, in the book Strange never becomes obsessed with bringing Arabella back to life after the Gentleman tricks him with the moss-oak double of her. Instead he goes immediately to Venice to grieve and to try and summon a fairy to teach him magic and become his servant. He does this solely because he thinks that fairy magic, long gone from England, is an exciting alternative to Norrell’s stodgy, respectable magic. Clearly the plot additions of Strange desperately seeking to revivify his wife and Norrell’s cold refusal to answer his letters or explain how he resurrected Lady Pole were added to heighten the dramatic conflict between the two.

Friendly Enemies

Yet that conflict is for the most part a half-hearted one and fated to end. It is quite different from what happens in Amadeus. Salieri hates Mozart and vows early on to destroy him, while Mozart is largely indifferent to Salieri. In contrast, Norrell and Strange have an immediate affinity that never completely disappears, and they grow more and more like each other in the course of the book. The abrupt change in Norrell’s initial skeptical, fearful attitude toward the second magician comes during their second meeting (their first meeting in the series), when Strange performs magic for him. “Mr. Norrell, who had lived all his life in fear of one day discovering a rival, had finally seen another man’s magic, and far from being crushed by the sight, found himself elated by it.” (p. 233) This elation is wonderfully conveyed by Marsan in one of the series’ best scenes (above).