Archive for October 2015

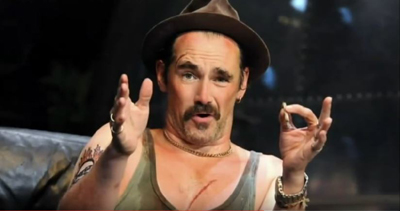

Mark Rylance, man of mystery

Kristin here:

I asked Rylance, a most certain Best Supporting Actor nominee, if success would spoil him now. He had a good retort: “I thought I was successful already!” Indeed, he sure is. But Hollywood will embrace him.

Will it? Well, it can try. It should try.

SPOILERS for Bridge of Spies ahead.

Another great veteran actor who came out of “nowhere”

Upon reading the reviews of Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies published over the past few weeks, many American moviegoers may have been puzzled by the fact that one of the most highly praised elements of the film was the supporting performance of Mark Rylance. Indeed, the praise was often unusually enthusiastic, with Rylance already considered a favorite for a supporting actor Oscar nomination or even win. I suspect that the vast majority of Americans have never heard of Mark Rylance, three-time Tony winner, two-time Olivier-award winner, Emmy nominee, etc. He fits the cliché of the “overnight success” who has been around for a long time and was, as he says, “successful already.”

In Bridge of Spies, Tom Hanks plays the lead, real-life lawyer James Donovan. In the late 1950s, Donovan accepted the unpopular job of defending a Russian spy, Rudolph Abel (played by Rylance), when he came to trial. Later he agreed to negotiate with the Soviet government to swap Abel for downed American pilot and spy Francis Gary Powers. Bridge of Spies is not one of Spielberg’s most exciting or endearing films, but it’s very well made and as classical in its traits as a film can be. It sits nicely beside his other historical dramas, Lincoln and the excellent Munich. On the whole the film has been well-reviewed, with a 92% favorable rating from all critics on Rotten Tomatoes, increasing to 98% among top critics. Rylance is clearly a major reason for the excitement.

It’s Rylance who keeps Bridge of Spies standing. He gives a teeny, witty, fabulously non-emotive performance, every line musical and slightly ironic — the irony being his forthright refusal to deceive in a world founded on lies. (David Edelstein)

Because this is Hanks we’re dealing with, audiences know what to expect, though the revelation here is Rylance (an actor Spielberg also cast as his forthcoming BFG), who appears utterly transformed — to the few who recognize his typically charismatic screen presence — into a balding, Eeyore-like gray moth of a man. (Peter Debruge; the reference is to Spielberg’s The BFG, with Rylance in the lead as the Big Friendly Giant, based on the Roald Dahl children’s novel and now in post-production)

Rylance, one of the greatest of contemporary stage actors, has to date had only an intermittent screen career, but Bridge of Spies suggests that could be about to change. He brings fascination and very, very subtle comic touches to a man who has made every effort to appear as bland, even invisible, as possible. (Todd McCarthy)

Brilliantly played by British theater legend Mark Rylance — who nearly steals the show. (Lou Lumenick)

Meanwhile, Rylance, who’s still probably best known for his brilliant work on stage, is the film’s real breakout discovery. With his musical Northern English accent and bemused, ironic demeanor, he turns a story that could feel as musty as a yellowed stack of old newspapers snap to exuberant life. (Chris Nashawaty)

Mark Rylance, the great English actor, director, and playwright who for a decade was the artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe theater, performs some mysterious act of alchemy in his role as the ineffable and unflappable Soviet spy. Almost without speaking a word, he communicates this character’s rich inner life, in which a near-Buddhist resignation to the whims of fate alternates with a feisty instinct for self-preservation. (Dana Stevens)

Part of the reason why the Germany sequences sag is that they don’t feature Abel, who is played by British actor Mark Rylance in what, with luck, will be a career-making performance. Many viewers may not have heard of Rylance, who recently played Thomas Cromwell in “Wolf Hall” on PBS. But his work in “Bridge of Spies” deserves to be widely recognized as an example of screen acting at its most subtle, poignant and exquisitely calibrated. (Ann Hornaday, who, like Friedman, does not acknowledge that Rylance already had made quite a career for himself)

I could go on, but for more see the reviews by Manohla Dargis, Richard Roeper, Kenneth Turan, and Michael Phillips.

I don’t, in fact, think that the German sequences sag. Basically the first half of the film covers the trial and sentencing of Abel, with brief scenes of Powers’ training for his spying missions flying over Soviet territory. Once Powers is shot down, Donovan goes to East Berlin for the negotiations, leaving Abel behind in prison.

The German sequences involve a marvelously authentic post-war East Berlin, designed by Adam Stockhausen, who won an Oscar for the production design of The Grand Budapest Hotel. (I wasn’t there in the early 1960s, of course, but I did visit East Berlin in 1992, when part of the wall was still up and the place had a very Soviet look, complete with giant busts of Marx and Engels.)

No, these scenes don’t sag, but there is definitely a niggling question in the back of one’s mind: When are we going to see Abel again? Rylance somehow makes this very ordinary-looking, quiet man the heart of some of the film’s best scenes.

Treading the boards

As Rylance pointed out in the quotation at the top of this entry, he already had an illustrious career going long before Wolf Hall and Bridge of Spies hit American screens. (The Wikipedia entry on Rylance  gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

Rylance also won awards playing a variety of very different characters. In 1993 he won his first Olivier award (the top British acting honor) for playing Benedick in Much Ado about Nothing, and followed that up with a British Academy Television award for the TV film The Government Inspector (directed by Peter Kominsky, who later directed him in Wolf Hall, for which he was nominated for an Emmy). He did a comic star turn in a 2007 staging of Boeing-Boeing and was nominated for another Olivier; he won his first Tony when the production moved to Broadway. His second Olivier and second Tony came for his performance as Johnny Byron in Jerusalem, first in London and then on Broadway.

Perhaps Rylance’s greatest success, however, came with a pair of Shakespeare plays done in repertory, Twelfth Night, in which he played Olivia, and Richard III, with him in the title role. Rylance had played Olivia at the Globe in 2002, but from November, 2012 to February, 2013, both plays ran in alternation in the West End. Later they transferred to Broadway, where Rylance was nominated for a Tony as best actor as Richard III and won for best featured actor as Olivia. The plays were done as authentically as possible, with men playing all the roles and wearing costumes true to Shakespeare’s era.

Ben Brantley conveys some of the excitement of these productions and Rylance’s performances in his New York Times review:

In this imported production from Shakespeare’s Globe of London, deception is a source of radiant illumination for the audience, while the bewilderment of the characters onstage floods us with pure, tickling joy. I can’t remember being so ridiculously happy for the entirety of a Shakespeare performance since — let me think — August 2002.

That was the last time I saw the Globe’s “Twelfth Night” (in London), directed by Tim Carroll and starring the astonishing Mark Rylance, in a bar-raising performance as the Countess Olivia. And how thrilled I am that our wandering paths have crossed once more, rather like those of the separated twins at the play’s center.

This “Twelfth Night” — which opened on Sunday in repertory with a vibrant and shivery “Richard III” that allows Mr. Rylance to show he’s as brilliant in trousers as he is in a dress — makes you think, “This is how Shakespeare was meant to be done.”

Walter Kaiser makes similar remarks in The New York Review of Books (available to subscribers only; in print in the February 6, 2014 issue):

The production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night by the English theatrical company Shakespeare’s Globe, currently at the Belasco Theatre, brings this play to life in a way I have only very rarely seen equaled in a Shakespearean production. The performances are so uniformly skillful, the interpretation of the play so intelligent and imaginative, and the costumes and stage set so accurate and evocative that the entire experience is exhilarating. Audiences at the performances I’ve attended have been overcome with delight, clearly somewhat surprised by the affecting immediacy of the theatrical experience they have undergone, unaccustomed to a Shakespeare so readily comprehensible and so vividly alive. You may, if you’re lucky, see another Shakespearean production that’s as good as this one, but it’s unlikely you will ever see one that’s better. […]

Mark Rylance, who over the past decade or so has made the part his own, is undoubtedly one of the greatest Olivias of all time. Frequently, this part is played with a grave, graceful maturity that tends to mask, or at least minimize, the intensity of the emotional quandary Olivia finds herself in when, not wishing to receive any further expressions of love from Orsino, she discovers that she has fallen in love with the messenger who delivers them. Rylance, instead, beautifully exposes her perfervid confusion: overcome with emotion, he stammers (in confirmation of Viola’s observation that “she did speak in starts”), acts with impetuosity, and manifests, at times, an engaging exasperation with his inability to control his passion. His hands alone, in the informative subtlety of their gestures, betray the emotions Olivia wishes to conceal.

I was lucky enough to encounter this Twelfth Night, as well as Richard III, in late 2012 when I was in London for a few days. I’m partial to authentic performance styles in theatre and music, so the chance to see two Shakespeare productions with all-male casts was appealing. Little did I realize that I would be seeing two brilliant turns by an actor I had never seen before–or so I thought. In fact, he plays Ferdinand in Prospero’s Books, but nobody, especially in such a small, bland role, can get much attention when playing alongside John Gielgud as Prospero.

Spielberg discovered Rylance in the same way that I did. In a very informative article based on interviews with Rylance and Spielberg, Jack Cole reveals:

Spielberg was urged to see Rylance in “Twelfth Night” by Daniel Day-Lewis. He calls him “a shape-shifter, a man of a thousand faces and voices who can play any part.”

“Seldom has an actor been around for so many distinguished years on the stage and yet had not been fully discovered for the screen,” said Spielberg by email. “Mark understands that the camera records stillness better than in any other media. His transition from the stage to ‘Bridge of Spies’ was graceful and invisible.”

Cromwell and Abel and beyond

Those members of the American public who did know Rylance before Bridge of Spies had probably encountered him as Thomas Cromwell in the BBC series Wolf Hall, a Tudor-era costume drama which aired in six parts on PBS starting April 6, 2015. (David and I streamed it more recently, mainly to see Rylance.) It seems unfortunate that the two breakout roles that have brought the actor to such prominence this year both involve notably restrained performances.

Anthony Lane compared these performances in his New Yorker review of Bridge of Spies:

So what’s it all about? It’s not about the U-2 missions, and certainly not about Powers, who comes across as a lunk. Nor, despite the set pieces in court, is it about the majesty of the law. No, the core of this movie is a standoff every bit as keyed up, and as gripping, as anything on the muffled streets of Berlin. What we thrill to is Rylance versus Hanks: the British actor, lauded for his stage appearances, but barely known to cinema audiences, up against the consummate Hollywood pro. You can see them prowling, probing, and wondering what the next move will be—or, in Hanks’s case, wondering whether Rylance will move at all. Admirers of “Wolf Hall,” on PBS, will have noted him as Thomas Cromwell, standing like a statue in the shadows, and realized, to their discomfort, that they could not look away. He does the same thing here, as Abel; we watch him watching everybody else, as if life were an infinity of spies. “You don’t seem alarmed,” Donovan says when they first meet, and Abel replies with a gentle question: “Would it help?” The Coens turn that into a refrain that beats through the movie, growing wryer and funnier each time—right up to the fidgety finale, where Abel is the calmest man in sight.

Of course, Cromwell does move in Wolf Hall. He moves a lot. Few television series can have shown their protagonists walking from place to place so often and at such length. Rylance modeled his gait on that of a Hollywood star, according to the Cole piece cited above: “He’s explaining how Mitchum, whom he adores, inspired his steady, rigid gait in the international hit series ‘Wolf Hall.'”

More Rylance on Mitchum, from another interview:

I’ve watched lots of films preparing for this, and I was particularly struck by one of my favourite actors, Robert Mitchum, how his performances haven’t dated in the way that even perhaps more versatile actors, Brando and Dean and people of that era, have. I noticed how well he listens, how still he is, how present he seems. You’re drawn towards the screen – wondering what’s he thinking, what’s he going to do next. That’s always the best way to tell a story.

Kominsky describes adjusting his filming style for Wolf Hall to catch Rylance’s subtleties:

The one thing you might not be expecting is that he’s the most minute of film performers. Nothing is overblown. Nothing is writ too large. It’s very, very simple, very understated, his performance, and then you look into his eyes, and it’s all happening. Everything is going on in there, and of course, you’re drawn into closer and closer shots, just to try and capture the emotion that’s going on very slight below the surface, and that’s what I loved to film. (From George Pollen documentary, Sky’s Arts program, 19:00-19:47)

As David has pointed out, however, the eyes as such are not always particularly expressive. It’s the area of the face that contains the eyes that does the job. The eyebrows and forehead usually give the context that tells us what the eyes are expressing.

If we concentrate on the upper half of Rylance’s face, the considerable differences between his Cromwell and his Abel become apparent.

As Abel, he consistently does something rather remarkable: he raises his eyebrows, creating furrows in his forehead, without widening his eyes. That’s not an easy thing to do. The result is a perpetually curious or surprised expression, a sort of mask that Abel wears to suggest that he is naive, innocent, a little slow. In fact, as we discover whenever he speaks with Donovan, he’s well aware of everything going on around him and has considerable insight into it. But it’s the naivete that allows him to dupe the agents who search his hotel room into letting him clean the paint off his palette, thus allowing him to conceal a key bit of evidence.

The key moment during which Rylance drops this tactic happens during his “standing man” anecdote, about a man he knew who survived a severe beating by Soviet agents by simply getting up again each time he was struck to the ground; Donovan reminds him of that man, he says.

As Cromwell, Rylance’s main tactic using his face is to glance away at nothing in the course of a scene where he is conversing with someone or observing interactions among other characters. So much classical editing depends on our understanding of whom or what a character is looking at, but not here. In one scene, Ann Boleyn shows him a drawing she has found hidden in her bed, depicting her decapitated. She asks him to find out who put it there.

Apart from his eyes, Rylance remains uttlerly motionless through the shot in which she holds the drawing out to him. Initially he is looking at her face (that’s the side of her head out of focus in the foreground) and then glances down at the drawing as she holds it up from below the frame.

He then glances down briefly to a point just outside frame right–clearly not at Boleyn’s face or anything else relevant to the action.

He looks at her face again and finally at the drawing.

Nothing here betrays Cromwell’s emotions, since he is a man who has to keep his thoughts hidden from most of the people at court. But that extra shifting of the eyes momentarily to an inconsequential space shows us that he’s thinking. Maybe he has an idea as to who would have left the letter. Maybe he’s thinking of Ann’s sister’s warning to him in an earlier scene, telling him not to help Ann. We don’t know here, as we don’t in many other scenes where Rylance uses this same sort of eye movement.

Both Abel and Cromwell need to conceal their thoughts, but Abel does so through deception and Cromwell through concealment, both conveyed by subtle acting.

In the Pollen documentary, Rylance describes how he avoids putting too much into a performance (in this case referring to lecturing on stage acting to students):

If I was only allowed three words, I could distill all my complicated notes, and you can see how wordy I get if I get talking, to three words, which would be “You are enough.” What’s happening to you is you don’t feel you’re enough, and you’re putting more effort into it than you should. You’ll be in the center of yourself, your voice will be centered, your movements will be centered, and the audience will also believe you more, because they’ll also believe that you’re enough. (8:35-9:08)

In Bridge of Spies, the little gestures and bits of business that Rylance uses to draw our attention to Abel are minimal. He wipes his nose occasionally, apparently the victim of a persistent cold or allergy.

As Michael Phillips points out in his review, this cold creates a parallel to Donovan, who has his overcoat stolen in East Berlin and soon develops a cold of his own:

It’s brilliant, really. What’s the quickest way to establish the humanity of two leading characters in a Cold War drama? Give them both the sniffles. […]

Because he’s relatively new to multiplex audiences, Mark Rylance will likely walk off with the acting honors for “Bridge of Spies.” He looks nothing like the real Abel, but in a largely nonverbal, supremely poker-faced performance — even his stuffy nose is subtle — Rylance suggests a forlorn practitioner of deception who recognizes a lucky break when he sees it.

(Agent Hoffman has also caught a cold by the epilogue; an occupational hazard, apparently, and a subtle comic motif.)

There are other gestures: lengthy tapping of a cigarette on an ashtray and little sucking movements of the lips, suggesting ill-fitting dentures. (A bit more subtle scene-stealing than that practiced by Steve McQueen in The Magnificent Seven, as described by David.)

Yet Rylance is perfectly capable of comic, broad performances as well. His Olivier-and-Tony-winning turn in Jerusalem was as a raucous, drunken rascal.

He made Richard III a grotesquely deceitful clown.

His Olivia, though more restrained, can do a broad comic take, as when she first notices Malvolio sporting the detested cross-gartered yellow stockings (see bottom).

We can assume that his acting as the BFG will be miles away from his performance in Bridge of Spies.

Will Hollywood be able to embrace him?

Roger Friedman claims that Hollywood wants Rylance. Possibly, but Rylance is ambivalent about filmmaking and generally prefers the stage. Indeed, I wish I had a reason to be in London right now, since he is back in the theater, receiving more rave reviews as the depressed King Philippe in a limited run of Farinelli and the King, the much-praised first play by Rylance’s wife, Claire van Kampen.

The Cole piece sums up Rylance’s on-and-off relationship to film acting, which involves Rylance being willing to embrace it rather than it embracing him:

For Rylance, embracing movie acting has been a circuitous journey. As a young actor, he watched as his theater contemporaries — Daniel Day-Lewis, Gary Oldman, Kenneth Branagh — became famous on the big screen. Agents urged Rylance into TV and film so that he would be “a complete actor.”

“I just, time and again, was attracted by the theater where I was offered better opportunities,” says Rylance. “I auditioned for films and didn’t get them. I think I had some stuff to learn about film acting. I don’t think I was personally really ready for it. But I did come to resent it. I did eventually think: Why, why? You wouldn’t tell the great Tamasaburo or Ganjiro-san it’s not enough to be a Kabuki actor, you need to be a film actor.”

He rattles off some film experiences he’s enjoyed: the Quay brothers’ “Institute Benjamenta,” a A.S. Bryatt adaptation “Angels and Insects” and a handful of British TV films, like “The Government Inspector.”

“But I’ve made some bad films, too, that have not been enjoyable,” Rylance said on a recent New York afternoon on a day off from starring in van Kampen’s “Farinelli and the King” in London. “At a certain point after one of them I did a few years back, I said, ‘That’s it. I’m not interested in this anymore.’

“I thought: I need to be happy with who I am, where I am. That can be the kind of miners’ dust of being an actor,” he says. “For an actor, being dissatisfied with who you are can be the reason for becoming an actor, but it can become an illness.”

But once Rylance let go of being a movie star, film directors started calling.

“As I did that, wonderful film things started being offered to me,” he says. “Maybe that was partly the problem — that I was giving it too much forced value. Because I grew up in America, so I grew up with some theater. But mostly I saw three films a weekend in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.”

Yes, Rylance was a Wisconsin boy, in a sense. He was born in Kent in 1960, and his parents, both English teachers, moved to Connecticut in 1962 and then to Milwaukee in 1969. There his father taught at the University School of Milwaukee, where Rylance first studied acting. “He starred in most of the school’s plays,” as the Wikipedia entry cited above puts it. Returning to England, he studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts from 1978 to 1980. His time in the States suggests why his accent is not quite the normal English one that we expect from the great British actors. It is nice to think that Rylance was avidly attending films in Milwaukee during the same period when David and I were doing the same here in Madison.

Clips of some of Rylance’s stage roles are included in the George Pollen documentary linked above; others can be found by searching on YouTube. Fortunately the wondrous Twelfth Night was recorded and is available on DVD (here in the US and here in the UK). The rest of the cast is excellent, particularly Steven Fry as Malvolio and Paul Chahidi as Maria. The many cameras used in the filming capture the most salient action at every point and alternate details and long shots to give a sense of where the action is occurring. As the image below shows, it was filmed in the Globe, with the audience right up against the stage and quite obvious (in a good way) in many of the camera setups. In the scene below, a spectator gives a wolf-whistle as Malvolio struts about his his yellow stockings, which strikes me as a very groundling sort of thing to do. Having seen the performance from the front-row center of the balcony, I am glad to have a closer perspective.

[December 2: Rylance has won the New York Film Critics Circle award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[January 3, 2016: Rylance has won the National Society of Film Critics award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 15, 2016: Rylance has won the British Academy Film Award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 28, 2016: Rylance has won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The story linked to here considered this an upset, as Sylvester Stallone had been widely predicted to win. But as I’ve shown here, a lot of us back in October knew better.]

[February 29, 2016: Rylance has been nominated for an Olivier Award for Farinelli and the King.]

[March 6, 2016: Pete Hammond of Deadline Hollywood has pointed out that Rylance won his Oscar without ever having participated in a single campaign event in the awards season. (He was given a day off from his current stage show in Brooklyn, Nice Fish, to go to Los Angeles to attend the Oscars ceremony.)]

[December 31, 2016: The Queen’s New Year’s Honours for 2017 include a knighthood for Rylance.]

Silent frame rates and DCP: A guest essay by Nicola Mazzanti

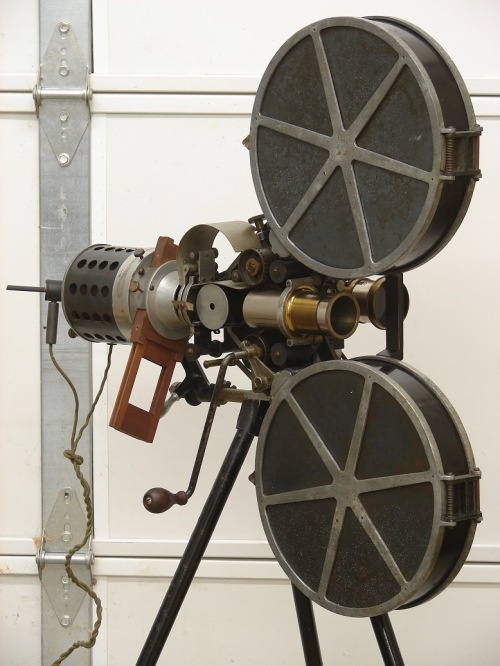

1914 Kinetoscope Victor Model I Silent Film Projector by the Victor Animatograph Co. From Pinterest, identified by Robert Van Dusen.

DB here:

The first thing you learn about silent movies is that they weren’t shown silent. The second thing is that they weren’t shown as fast as we often see them. Screened at 24 frames per second (“sound speed”), many films look rushed and silly. Those were shot at slower frame rates, like 16 fps or 18 fps. By the end of the 1920s, though, some were shot faster than sound, up to 30 fps.

Most archives and some cinémathèques and repertory theatres owned adjustable-rate film projectors, so they could provide a smooth flow of motion for most silent films. But what happened when film projectors were junked and replaced by digital projectors? How could the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), that set of files containing the movie and a host of encryption devices, offer the various “silent speeds”?

I wrote a little about this problem in Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies, but afterwards I continued to wonder how archives were coping with the matter once digital conversion was universal. The main problem is that digital projectors don’t currently provide options slower than 24 fps. Both the Hollywood studios that established the digital standard and the manufacturers that implement it simply ignored the history of cinema. Where does that leave archives, which restore, circulate, and show silent films on digital equipment?

So I asked our friend Nicola Mazzanti, Curator of the Cinematek in Brussels, about this problem. Nicola is one of the founders of the Bologna Cinema Ritrovato festival and a major consultant about digital cinema and the preservation of films in the new age. Here’s his typical provocative, pro-active answer.

Why can’t we ever make it simple?

Nicola Mazzanti, Brussels summer 2011. The plaque reads: “Mr. Bill Clinton, President of the United States of America sat at this table on 9 January 1994. He drank coffee and chatted an hour with all present.”

When they try to sell you some new product there is always the sweet thrill that now, finally, all the unpleasantness and the drawbacks, the little things that bothered you in the past, will be gone forever. Then, you realize that the car you bought was a Volkswagen diesel.

With Digital Cinema we were all told that life would be happier once we jumped onto the bandwagon. Distribution of independent films would be easier. All sorts of catalogue titles would flow joyously from the archives to the multiplex. “Alternative content,” including slightly unsharp TV programs and opera with awful close-ups and great sound, would make theatre owners rich.

Many believed the PR. Some of this became true—the usual 10% of it.

Granted, it is easier and cheaper to produce and manage a DCP than a 35mm print. And some classics did find their way to independent or repertoire theatres (the few who survived the digital switch, that is). Several archives, ours included, are enjoying these benefits of the digital switchover. And advertising an 8K or 20K or whatever-K restoration can bring in audiences. But many of us also have tons of perfectly fine 35mm of classics, and they cannot be shown any more. Why not?

*35mm projectors are basically gone.

*Some catalogue owners permit screening only their “restored DCP” (and strictly with English or French subtitles – so much for cultural diversity!).

At the end of the day the number of available classic titles went down, not up.

We could talk about this situation a long time, but let’s home in on one effect of the digital transition. The story I want to tell today is one about those “technical details” that we seem never able to get right. Only the Gods of Cinema know why.

We could talk about screen ratios in this connection, but not today. Today we talk about frame rates.

Toward a standard

Unlike video files but like a strip of film, a DCP consists of a bunch of individual frames that play nicely one after the other. The number of frames that are played back per second is defined by a simple line of code in an XML file. From the point of view of the technology in the server and the DCP format, there is no reason why we cannot play a film at any rate we like, say, 17fps. (Granted, we can’t really run it at 100fps, because of bandwidth, but you see my point.)

This is not the whole story. First of all, there is a need for a highly standardized system, or we would have the problem of a DCP playing well in one theater and at the wrong speed in the next. Then there are other issues, like the frequency of the projector or the link between the server and the projector. I will not bore you with the details. In sum, technical problems make it impossible to build what I had proposed in the first place: a hand-cranked digital projector. (I was serious.)

Yet all these technical problems could be solved, if we took a rather pragmatic approach. (Here, “pragmatic” is the PC term for “compromise.”) That’s what we archivists did, a few years ago.

At the time of publication, the Digital Cinema Initiative specs described something that did not really exist yet. The technology was only almost there. In the hurry to produce a standard that could work, it was perfectly sensible to start with only two frame rates: 24 and 48 (for 3D).

Some time later though, the issue of expanding the frame rates options came back with a vengeance. The strongest push was coming from European broadcasters who wanted to sneak their boring stuff to the cinema screens and thus called loudly for a 25fps frame rate. Then some filmmakers like Peter Jackson and James Cameron fell in love with the idea of higher rates, like 30fps and 60 for 3D (regardless of how this would balloon production budgets).

Soon the issue became geopolitical, with the Europeans pushing hard for 25fps, mostly because they considered it a victory to impose another standard on the Americans—even though they had lost the digital war as a whole. At the end, the Pandora’s box of frame rates had to be reopened, enthusiastically by some, reluctantly by others.

The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE) set up a workgroup where all strong views in favor or against were represented. For the historians among you, it was first called “DC28-10 Ad-hoc Group on Additional Frame Rates” and later “21DC.10 AHG Additional Frame Rates.” We archivists, following our typical model of guerrilla resistance, sneaked onto the panel.

Technically, the archival force was the Technical Commission of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). Actually, it was Torkell Sætervadet and I who were volunteered for this “mission impossible.” Torkell is the world’s greatest expert on projection. He wrote the indispensable handbook for film projection, The Advanced Projection Manual (2006). His FIAF Digital Projection Guide, another must-read, was published in December 2012, the year film projection disappeared.

Torkell and I worked on the frame-rate problem for a couple of years. We mostly revised documents and conducted conference calls late at night (thanks to European time zones). We received some support from the more corporate members of the Workgroup. Many had never heard of lower frame rates, and the concept actually fascinated them. We also benefited from the support of Kommer Kleijn from IMAGO (the European version of the ASC), Paul Collard (then Ascent Media, now Deluxe, a profoundly competent person in the business), and Peter Wilson of High Definition and Digital Cinema Ltd.

The result: We succeeded to a great extent. We convinced the workgroup that silent rates had to be part of digital projection. True, the new standard allows only four other rates: 16, 18, 20, or 22. (To be extra-precise, due to technical issues, 18fps is in fact 18.18181818 and 22 is really 21.8181818.) But four options are quite a lot, and we decided that four were better than none.

So what we called the Archive Frame Rates standard (technically ST 428-21:2011) became part of the SMPTE standards for Digital Cinema. It can be found here. More or less in parallel, other frame rates were allowed: 25, 30, and 60fps. An announcement of this development, with commentary, can be found here.

Hurray! But don’t celebrate yet.

The Archival Frame Rates standard is not a mandatory one. The manufacturers of Digital Cinema projectors never implemented this particular standard in their machines. And archives all over the world never requested it before purchasing a projector. That, today, is the roadblock to proper screening of silent films on adjustable digital projection.

Home-made silent speed

Well, what are the alternatives?

One can produce, for example, a normal DCP at 24fps, and then use a simple piece of software (such as EasyDCP) that allows for different speeds if the DCP is played back from a computer. That feeds directly into the projector, bypassing the projector’s server. It works fine, although you have to try out several frame rates until you find the one that does sit well with the refresh rate of your projector. Otherwise, you might have some artifacts onscreen.

Alternatively, if your film’s chosen silent speed is 16fps you can easily triplicate each frame and create a 48fps DCP which would play in most theatres. 20fps would fit into 60fps, when available. For 18 and 22, however, this is no solution; they are tough frame rates anyway.

The problem with these as hoc solutions is that they are not universal. If an archive ships a DCP to another archive, someone acquainted with that file must be in the booth with a computer. Or you can just send the DCP and hope it works. Either of the two digital solutions can be used safely only in your own theatre, basically.

Hence my interest in pushing for a standardized solution. This is, I’m convinced, the best one for bringing silent films to broader public.

So I haven’t given up hope that one of the manufacturers might realize that the Archival Frame Rates standard would be a nice addition to their option package. Particularly if archives and other potential buyers start asking for it.

Does one speed fit all?

The silent frame rates are more complicated than what I’ve just outlined. Let’s go a little deeper, because it’s interesting.

When we refer to frame rates, we tend to use discrete numbers (16, 18…). But like all things analog, frame rates lay along a continuum. That ranged from 16 (sometimes lower) to 24 (sometimes higher). Anybody who worked as a projectionist knows that even with a modern projector equipped with speed variators, the actual speed can change according to the day of the week and the time of the day, depending on fluctuations on the grid.

The same variations occurred, naturally, with hand-cranked projectors and cameras. And early motor-driven machines used in the silent era also suffered unpredictable variations from moment to moment.

As a result, silent films were shot and screened at different speeds. Even the same film would have fluctuations in frame rates from scene to scene or shot to shot.

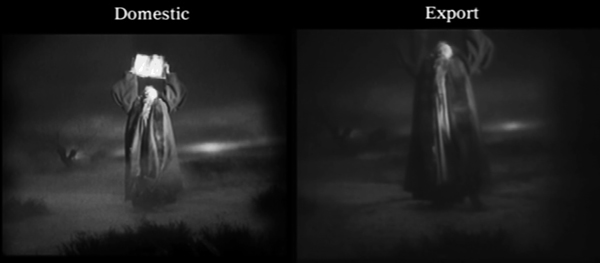

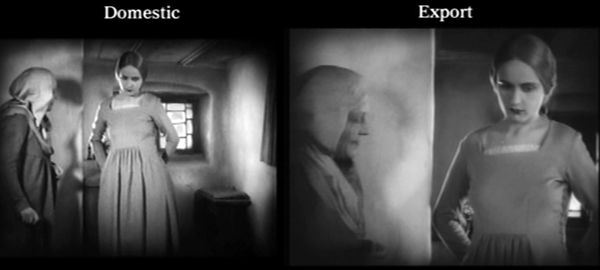

The best example I know personally is Murnau’s Faust (1926). When Luciano Berriatua and I were analyzing the existing negatives of the film, we were puzzled when we compared the two negatives from the original production. Each negative was shot with a different camera. As was common in silent film, the filmmakers provided one negative for domestic circulation and one for international distribution. In production the cameras yielded different angles on the scene–sometimes quite similar, sometimes different.

Nevertheless, the action each one captured was identical. The problem is that the two negatives were different in length!

Why? The cameras were operated by two different cameramen, each hand-cranking at a different speed. The assistant cameraman, undoubtedly younger and more enthusiastic, was cranking faster!

Such a disparity was not uncommon. On the contrary, any archivist confronted with the decision about “suggested frame rate” for a given film is confronted with a choice among many different frame rates. What one writes on the cans is always a speed that fits better on average, not necessarily on each individual shot or scene.

And the reality in archives, cinemathques and everywhere else, is this. Most silent film screenings, if not virtually all, are today executed at one speed throughout the whole picture,

There is strong, albeit anecdotal, evidence that projectionists in the silent era were encouraged to crank different sections of a movie at different speeds. Cues in some musical scores suggest that sequences may have been slowed or speeded up. Projectionists may also have chosen to accelerate chases and battles or slow down love scenes. But there’s no way to know to what extent this manipulation was a common practice.

Personally, I think that we are inevitably looking at a silent film with modern eyes. For one thing, we have a completely different approach to continuity. We ask that a restored silent film be perfectly graded, that its tinting and toning be consistent from shot to shot and scene to scene. But when we examine an original print, particularly from the ‘teens, we realize that our modern concept of pictorial continuity did not apply. It seems to have come into play in the late Twenties or later. Our assumptions about continuity make us consider narrative or visual discontinuity a technical error, or at least a trace of a more cavalier attitude towards continuity. I think that discontinuity of technique was often voluntary and sometimes deliberate.

Fun with frame rates

This point applies to frame rates as well. I am convinced that audiences in the silent era were much more relaxed towards something that we now consider so important. Otherwise, it’s difficult to understand why there so many variations in speed within one picture, and between different versions of the same film.

We should remember as well that we cannot really discuss anything “silent” without taking into consideration that it was a long and complex period of fast evolution and change. A film from the early ‘teens and one made ten years later are two different beasts, and different considerations should apply.

So, to return to our main theme: Are frame rates impossible to vary with a DCP? No—in theory.

If you decide to create your DCP at 24 fps, you can easily slow down each scene at a different rate, if you so choose. Alternatively, if the Archive Frame Rates standard were in use, you could apply your four fixed speeds (16. 18. 20. 22) to different sections of the DCP by simply creating separate “reels” and a correct playlist. This would be a bit like a DCP in which certain parts, such as the restoration credits, are actually a separate file to be played before or after the main body of the film.

Have I tried this? No. Could it work? Yes. Is it worth trying? I am not sure. Again, I am afraid we are looking for a precision that was not really part of a film screening in the silent era.

I remain strongly convinced that “old stuff,” including silent film, has an appeal for the public, and not just for few cinephiles. I also strongly believe that an archive like ours in Brussels should offer a wide range of films on DCP for screenings around the world.

In order to show a silent film in the present environment I have to do some nasty things to the images. I have to slow them down by means of software, even if some solutions work well enough to fool some archivists and historians.

If the alternative is never to show Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910) to anybody, I’d rather use some tricks to make the screening possible in a modern DCP environment. That’s better than making the film invisible. I am also old enough to remember how horrible it was in the 35mm days when there was really no way to show silent films outside a cinematheque. While we wait for archives and manufacturers to implement the fuller range of options, we must keep our films alive.

So when today a nice audience shows up to see Maudite with a pianist in a multiplex in the middle of Flanders (or Ohio or Nebraska), I admit that I’d be unhappy that I had to trick the speed to 18 fps. Yet I still consider it a victory.

For discussion of silent-film frame rates the standard point of departure is Kevin Brownlow’s 1980 article, “Silent Films: What Was the Right Speed?” Brownlow suggests that many American silent films were intended to be screened at a higher rate than the cameraman had used during filming. See also James Card, Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film (Knopf, 1994), 52-56, and Jon Marquis, “The Speed of Silence” (2011). On the revival of interest in high frame rates, see this 2011 article and Pandora’s Digital Box.

Nicola has written about other aspects of film preservation in the digital age. See his recent contribution to“The Last Picture Show,” a symposium in Artforum (October 2015), 288-291.Tacita Dean and Amy Taubin contribute to this as well.

The magnificent Masters of Cinema DVD set of Faust includes both the domestic German version and the export version, along with a lengthy comparison of them, from which I’ve drawn my illustrations.

Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910).

THE PRESTIGE, one way or another

DB here:

Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel we have now posted an analysis of sound in Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige on our site. It sits along with others under the rubric Books>Film Art. Or you can go directly to it.

It was originally included in the last couple of editions of Film Art: An Introduction. Why is it here now?

One of the most original aspects of Film Art from the beginning (1979) was our belief that for each technique we surveyed (cinematography, editing, etc.) we provide one example of how the technique functioned either in an entire sequence or across a whole film, or both. This, we thought, would get beyond one-off technique-spotting (“The low angle makes him look powerful”) that was common in other texts.

For several editions our sound chapter examined a sequence from Bresson’s A Man Escaped, while tracing how its use of sound fitted into the film as a whole. But we were told that the example was becoming problematic for teaching, because students had trouble concentrating on the sound while reading subtitles. So we put the Bresson analysis up on this site and I wrote something new on The Prestige (still my favorite Nolan film).

It turned out very lengthy and somewhat more intricate than our other analyses, partly because of the plot’s boxes-in-boxes structure. (One guy reads another guy’s journal, in which he’s reading the first guy’s journal….) So, because we had to keep within space limitations, we replaced the Prestige analysis with a briefer one of sound in The Conversation, co-written with Jeff Smith. That film, to be fair, is probably more frequently taught than the Nolan.

On the bright side, I’m happy that the Prestige analysis is likely to find new readers by being openly available on the Net. Had things gone differently, we’d probably have adapted it into a chapter of Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. But then you’d have to pay to read it, and now you have it for free.

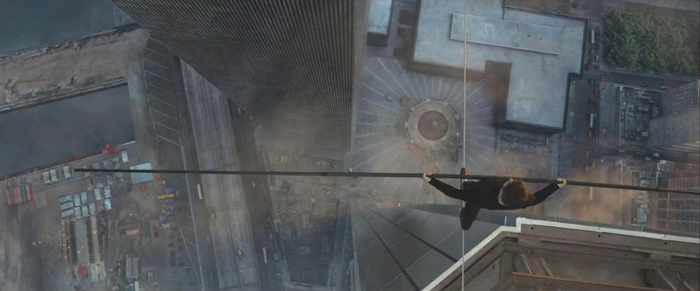

Our new edition, number 11, of Film Art will be appearing early in 2016. Kristin, Jeff, and I have added some new things to it and its online progeny. We’ll be previewing more of it in the weeks to come. In the meantime, let’s just say FA 11 includes a new analysis of another film. Look at the cover below and guess which one.

Apart from our Nolan book and the entries it’s based on, I study another aspect of The Prestige here.

Talking THE WALK

Kristin here–

David and I saw Robert Zemeckis’ The Walk the day after it opened. The screening was 3-D Imax, since the film originally opened only in Imax theaters and went wider on October 9, already with the odor of box-office failure wafting over it. We enjoyed it. It’s not an undying masterpiece, but it’s certainly better than many of the reviewers seem to think. In particular, they largely ignore the first portions of the film and imply (or outright state) that you should sit through them because the climactic sequence, protagonist Philippe Petit’s very high-wire walk between the Twin Towers in New York is worth it. David Rooney’s review for The Hollywood Reporter boils down the dismissive attitude toward the early portions: “The film’s payoff more than compensates for a lumbering setup, laden with cloying voiceover narration and strained whimsy.” Peter Debruge’s Variety review is an exception, dealing with the earlier scenes insightfully.

The view from Lady Liberty

I was surprised to see that Matt Zoller Seitz, one of our best reviewers, gave The Walk a mere two and a half stars. Starting to read his review, I was expecting that he might dismiss the early part of the film as too lightweight and comic to balance the spectacular set-piece of Petit’s performance or something of that sort. Instead, his primary objection to the film is the voiceover and sometimes to-camera narration delivered by Petit, who is shown as standing atop the torch of the Statue of Liberty. More specifically, the film opens with a tight close-up of Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Petit staring directly into the camera against a pale-blue background and saying “Why?” What follows, he says, is to explain why he made his famous walk. The camera then pans to an extreme-long shot of the World Trade Center, pulls abruptly back to reveal the Statue of Liberty (above), and cranes up to Petit standing on the torch.

The rest of the film consists of a series of flashbacks told from this imaginary space, for surely we are not to imagine that Petit ever really climbed the torch. Like it or not, a certain whimsical tone is set up concerning the process of his telling his tale. The film returns to this narrating situation at intervals, usually only for a single shot and usually for a transition into a new scene, with what Petit says in the fantastical present bleeding over into that scene to set it up.

Seitz’s objections to the narration are two. First, he sees it as an attempt to, in a sense, “sell” us The Walk through the enthusiastic tone of the narration. Second, he considers the narration to be redundant, adding almost nothing to the visuals. His prime example of the latter is the scene in which a seagull briefly hovers over Petit and his voiceover comments on its sudden appearance.

The idea that the narration was annoying or redundant never occurred to me when I watched the film for the first time. After reading Seitz’s review, I considered writing this entry and went back to see the film again. I still didn’t find the narration problematic. I think that it contributes to The Walk in a variety of ways. Possibly some of it could be cut, but most of it functions in ways that go beyond what is conveyed through images and dialogue.

Take the seagull scene. Without narration, it could create suspense. Just before it appears, Petit has lain down on the wire, and the voiceover speaks of the serenity of the sky and clouds. Suddenly the bird is hovering right above our hero. The logical reaction would be to worry that it’s going to strike him, break his concentration, somehow threaten him. The voice continues: “Then, something appears. An apparition! A bird. This bird is looking at me! I feel this silent threat.” (The bright-red rims of the bird’s eyes may be a subjective rendition of Petit’s reaction.) The threat he feels, however, is not that the bird will harm him. Instead, he is “invaded by doubt” and decides that it is time for him to end his walk. His narration is not telling us simply that a bird has appeared, but that he takes it to be some sort of symbol of threat. It marks a turning point in the Walk, one which we can only grasp because he tells us that it does. If he had not spoken, what would we have? Presumably Petit seeing the bird, getting up, and continuing his walk. Perhaps he would have a look of doubt on his face, and the music might go into a minor key. Still, we would not know specifically that the bird has caused him to decided to end his walk, because he does not do so for some time after that point. The narration is not simply redundant.

More generally, I think the narrating situation and the treatment of the story as a series of flashbacks with occasional voiceover have two major functions. First, the narration clearly establishes that Petit survives the Walk. Sure, a lot of people walking into the theater know that the historical Petit did survive it and is still alive. Some of us are old enough to have seen or heard news coverage at the time, while others may have read his memoir To Reach the Clouds, upon which the film is based, or seen James Marsh’s 2008 documentary, Man on Wire. Younger moviegoers may have read infotainment coverage of Zemeckis’ film. But there are undoubtedly also people entering the theater knowing nothing about Petit. For them, the film needs to establish his survival if they are not to watch the Walk sequence in constant suspense over whether the protagonist will survive it. The very first word he speaks, “Why?” deflects us from anticipation of the Walk as a spectacular stunt to a curiosity about its significance.

Second, Petit-as-narrator sets the tone for the film, a tone which would perhaps be sufficiently conveyed by the visuals, the action, and the music in some scenes, but not, I think, in others. The tone is light and comic and enthusiastic in the first half of the film, though it shifts later, for reasons I’ll get to in a minute.

Third, the narration helps to break the parts of the film into three separate genres: a romantic comedy (the first half hour), a suspense film (from roughly 30 minutes to 86 minutes), and a lyrical, psychological character study thereafter. The narrational tone changes with each, from ebullience to simple reportage to reflective inner monologue.

David and others have suggested that overall The Walk is structured somewhat like a heist film. In heist films there is emphasis on planning and preparing, with everything explained ahead of time and in intricate detail. The long process of the lead-up is as much the point, or more so, than the actual moment of the theft. (In the review linked above, Debruge points out that “Much of what made ‘Man on Wire’ so thrilling was the fact that Marsh had approached Petit’s story like a caper film.”)

Even though Petit’s goal is not to steal some fabulous treasure from a seemingly impregnable location, his Walk is technically a crime. Still, it is a crime that he cannot conceal, and unlike the masterminds in heist films, he presumably is resigned to the fact that he will certainly be arrested. And unlike in the heist film, there is no planning for an escape and no escape scene. Petit will triumph as long as he completes the Walk before the arrest.

Yet some critics, whether or not they like the film, have ignored or dismissed the rest of the film and focused on the climactic walk as if it is (or should be) the whole film. Some of them, at least, want to treat The Walk as a suspense-filled action film. Yet this is not simply an action film with a boffo climax. Why, though, separate a film into acts in three genres? I think it is because the film wants to clear away the more obvious conventions of a Hollywood films of this type during the early portions of the film. These then drop away in order to allow the Walk sequence to be pared down, without romance and with muted suspense, to a lyrical focus on the peace and beauty of Petit’s perambulations back and forth above the city.

The rom-com

During the first half of the film Petit courts Annie, charms Rudy into helping him, and finds two other “accomplices” to help him fulfill his dream. It’s all a bit like Amélie in tone, with a hint of Jules and Jim in the music. We have to be won over by Petit to some extent if we are to take an interest in anything about the Walk except the facts that the man made it from one Tower to the other and back a few times and that it sure looks great in 3-D Imax.

Some critics clearly weren’t won over. Others were. Debruge points out, “Say what you will about the accent, but Zemeckis and co-writer Christopher Browne have captured Petit’s voice — the real, honest-to-God way he expresses himself — and by channeling that, the actor successfully wins us over from the outset, hanging out in the Statue of Liberty’s torch.” If my own reaction is any indication, one can find Petit a bit hard to take at times and still consider his narration, Lady Liberty’s torch and all, an asset to the tale.

In describing classical Hollywood cinema, David and I have repeatedly pointed out that films in this tradition usually have two plotlines, one a romance and the other to do with work or danger or some sort of project. These two plotlines tend to be connected, with the romance somehow linked to whatever else is happening in the protagonist’s life.

In The Walk, the romance is there, but it is minimized. The development of the attraction between Petit and Annie is squeezed largely into the first quarter of the film. It moves very quickly once we get past the meet-cute antagonism between them over Petit’s stealing the audience listening to Annie’s street singing. Almost immediately they are in a cafe, sipping wine and discussing his dream over a little improvised model (above left), and then in his apartment, with more wine by candlelight and discussion of the dream over a photo of the Twin Towers. The two seem already to be a couple. It’s as if the romance progresses offscreen, in scenes that we don’t witness–the first kiss, the moving in together.

Annie raises no objections to Petit’s crazy goal, as one might expect her to. There is little sense of how much time has passed. All we know is that Annie urges Petit to fulfill his dream, and she becomes his first accomplice. For the rest of the film, she will be little more than first among the accomplices and an onlooker to the preparations and the Walk. Apart from a quick kiss and her loyal overnight vigil outside the Towers as Petit and the other accomplices invade the buildings and set up for the Walk, Annie has almost nothing to do during the preparations for the Walk and the Walk itself. She does, however, get to characterize the lyrical part of Petit’s achievement. Later, when Barry remarks now New Yorkers love the Trade Towers, Annie adds that Petit has brought them to life for people and given them a soul. The romantic plotline is further undercut almost immediately, however, when Annie unexpectedly leaves Petit to return to France and find her own dream.

During the first half of the film, Petit’s narration is humorous, bumptious, perhaps a little too ingratiating, depending on your taste. He might seem a bit annoying and capricious, as young men often are in rom-coms. The implication may be that the quirks of his personality are part and parcel of the genius and drive that allow him to perform the feats he does, as his cocky little smile upon being arrested for walking between the towers of Notre Dame suggests. (Note that Barry, who eventually becomes the “insider” accomplice once the team arrives in New York, says he had witnessed Petit’s Notre Dame walk, and sure enough, there he is in the back of this shot and visible in another view of the crowd watching.)

If Petit is selling anything, it’s not the film but himself, and we do not need to like him to admire him.

The suspense film

Petit and his accomplices to go New York at roughly the midway point of the film, and The Walk segues temporarily into a suspense film. Where one might expect the Walk itself to be the section designed to ramp up suspense in the audience (as many critics did), the more conventional suspense-generating actions are more prominent in the preparation for it, which constitutes the third quarter of the film. This takes place from 55 to 86 minutes. It begins at the airport, with a comic scene of a customs official reeling off the contents of Petit’s equipment containers (above). When he asks what the equipment is for, Petit cheekily replies that he’s planning to use it to walk between the Twin Towers. The official unconcernedly allows him through.

Soon the tone becomes more serious, as Petit visits the Towers and is overawed and intimidated to the point of feeling that his plan must be abandoned. Standing in the lobby of the South Tower, he speaks of feeling that there is no way to get to the top. Immediately a service door behind him swings open, a worker appears and greets them, and the man departs, leaving Petit to investigate the room beyond, discovering a stairway to the top.

Soon he emerges on the top of the building, tries teetering over the void on a projecting metal girder, and is clearly ready to take up his dream again.

Eventually the tone of the Development turns more tense, as Petit obsessively goes over the plan with his accomplices and the day of the “Coup” approaches. Late on the night before the group invades the Towers, Petit awakens and nails shut the “coffin,” a crate containing the equipment, and expresses his doubts to Annie. Ebullience has become dead seriousness, though Petit determinedly avoids referring to death.

Once the actual invasion of the Towers begins, the tone ratchets up the tension and the delays typical of a Development portion occur. Although the team’s fake delivery truck is admitted to the loading docks, a lack of access to the elevators nearly scuttles the plan. Once Jeff and Petit are on the unfinished upper stories of the South Tower, a guard interrupts them as they unload their equipment in the unfinished upper stories of the South Tower. They end up hiding for fours astride a metal girder above an unfinished elevator shaft extending down so far that we can’t see the bottom. Jeff, who suffers from a terror of heights, becomes our identification figure briefly, as he suffers through this ordeal. Later, once they are on the roof in the dark of night, a guard comes up with a flashlight and nearly bumps into Jeff before being lured away to a lower floor by a colleague offering to share a pizza.

As dawn approaches, the threats to the success of the Walk continue. An arrow is shot from one Tower to the other to begin the process of hauling the wire across teeters on the corner of the building. The bracing wires are loose, and Petit must drag a terrified Jeff onto the side of the roof to help tighten them. At dawn, a mysterious man in a suit visits the roof, apparently just for the view, and sees them. After a nerve-wracking face-off, he ultimately leaves without challenging them.

Interestingly, during this face-off, Petit picks up a length of pipe. After the man leaves, Petit seems shocked to find that he has been holding it in a potentially threatening fashion. This is the only hint we ever get of the lengths to which he might go to make his dream succeed.

There is also a good deal of exposition in this section of the film, part of it accomplished by the narrating voice, setting up for what will happen during the Walk. As a result, we don’t need to be told about the technical details during the Walk itself. There is, however, a fairly long stretch with no voiceover leading up to the silent confrontation with the mysterious man. After he leaves, Petit’s narration notes, “And that was the moment in my adventure that I call ‘the mysterious visitor.'”

This last incident works in with the many other bits of good luck that have allowed Petit to accomplish his dream, including the fortuitous opening of the stairwell door mentioned above. It adds a touch of suspense, as well as realism. Such things do occur–and in this case, really did occur.

The lyrical walk

Romance and suspense having been presented and set aside, the film defies convention by switching into lyrical mode. In a conventional film, the grandeur of the mise-en-scene would become a terrifying void (especially in 3-D) into which we constantly fear Petit will fall. Instead, to a large extent because of the narrating voice and the music, we instead follow Petit’s exhilarated reaction and his every shift of mood. For instance, when he stands with one foot on the wire and pauses before beginning his Walk, subjective mist gathers (see bottom). It conveys his sense of the rest of the world disappearing and his attention focusing entirely on the wire. His voiceover describes all this. Would we otherwise perhaps take this mist to be an actual passing cloud?

Similarly, when he finishes the first crossing and starts back, would we understand why if we had only the image and music? Or when he kneels during the return trip to the South Tower, would we grasp that he is saluting the wire, the Towers, and so on, if his narrating voiceover did not tell us?

There are details that set up some suspense but are at the same time tied to Petit’s emotional reactions. He remarks that one of the the cavaletti holding the bracing lines onto the wire being upside down. This seems initially to be used as an occasion for Petit to mention his gratitude to Rudy, though it also sets up for the later moment when the plate threatens to buckle under the strain–a moment which ultimately comes to nothing.The detail shot of Petit’s shoe during this scene sets up some suspense, in that a small, wet patch of blood suggests that he may later be endangered by the wound from stepping on a nail. Later we see more blood on the shoe, but the wound in fact never causes him to falter. In this close shot, the shoe also conveys a visceral sense of the moment of the walk and reminds us of the practice that has gone into it, imprinting a channel where the wire has pressed into his foot.

Of course, we are unable entirely to view the scene without suspense, as our bodies naturally react to the strong illusion of height created by the extraordinary CGI imagery and the 3-D. The word “suspense,” after all, derives from the notion of dangling in space. Yet the film constantly backs us away from such jitters in part through the soothing voiceover.

Suspense also returns to some extent just after the salutes, when the police appear, initially on the South Tower end of the wire. An even greater threat, a police helicopter, eventually appears.

These authorities offer or threaten to help Petit off the wire, endangering him in the process. His evasive maneuvers and defiance create humor that somewhat dispels the suspense. Ultimately, by tossing his balance pole at the outstretched hands of the startled police, Petit manages to clear the way for a triumphant exit from his Walk. This conclusion assures that he controls the entirety of his feat, despite the fact that he is immediately arrested. The applause of the workmen on the lower levels as he is escorted out confirms his triumph, as does the praise offered by one of the arresting officers (seen at the left below). The voiceover description of his later minor “punishment” of performing a lower-wire act for children in Central Park confirms that he has successfully defied even the law.

Zemeckis, classical director

While Zemeckis has a reputation as a master of the action set-piece, he can also construct a tight classical narrative. Seeing The Walk a second time for the purpose of writing this entry, I realized that the script is very carefully put together to set up for everything that will happen, both causally and in terms of information.The arrest in Paris makes it clear to us that Petit will face a similar punishment after his Trade Towers Walk. Petit’s fall from the wire in the circus tent and Rudy’s emphatic advice that the last three or four steps are the most dangerous foreshadows the similar moment at the end of the Walk where Petit momentarily looses control and his trembling makes the wire itself shake. In many cases, the voiceover plays a vital role in setting up things to come.

Perhaps it’s not as perfectly put together as Back to the Future, but then, few films of the past decades in Hollywood are.

As David noted during our first viewing, the film also has a good, old-fashioned Hollywood visual motif. Round shapes are contrasted with straight lines, the round ones being associated with Petit’s early ground-based entertainment career and the lines with his high-wire acts. The lines may be obvious to viewers, as when Petit draws a line between the Towers in an image, or less so, as in the scene where an arrow is tested as a means for starting the process of sending the wire from on Tower to the other.

Unfortunately none of the video material currently online shows portions of the street-entertainment scene of the film’s early section, so I can provide no images of the round items. These include the perfect chalk circle that Petiti draws to delineate his performance space, the top hat in which he collects coins, the red-and-white candy mint, his unicycle’s wheel, the ring under the White Devils’ tightrope in the circus tent, the arch in the same ring that frames Petit when he juggles to impress Rudy, and the umbrella he uses to shelter Annie in a sudden rain shower.

Such imagery disappears in the second half, apart from repeated overhead shots of the circular fountain on the ground between the Towers, often with the lines of the wire and the balance bar juxtaposed with it (see top). It recalls Petit’s initial performance space on the ground and subtly reminds us of how far, and high, he has come since then. (During their first meeting, Annie remarked of Petit’s tightrope, “That was the lowest high-wire I’ve ever seen.”)

In the end, the answer to the original question, “Why?” is that “There is no why.” When Petit sees a beautiful place in which to place his wire, he feels compelled to do so. His motive is not to show off his derring-do or to spice up his life with risk-taking. His is an aesthetic compulsion, and the Walk is referred to a number of times as an artwork. The form of the film reflects that compulsion.

The last lines of the film return to the Towers themselves. Petit narrates over a shot of himself returning to visit the top of the Towers, telling us that an official gave him a pass to visit it. We return to the torch atop the Statue of Liberty, where he looks at the card and says, “He wrote on it ‘Forever.'” This could have been told visually, I suppose, but it would have meant close-ups of the card, probably a second person on the roof to whom Petit could explain his card–something, at least, more elaborate and less effective than simply having him tell us this information. A pan moves us toward the Towers, gleaming in the sunshine until the slow fade-out that conveys the fact that for the Towers, forever was cut brutally short. That final salute, at least, seems to have pleased everyone.

As I said at the outset, The Walk is not necessarily a masterpiece, but it is far better than some of the reviews would claim. Seeing the film a second time, I enjoyed it more and found new things to notice, which is always a good sign. I did not find the voiceover narration annoying during either viewing, and it isn’t really dispensable. The film is worth seeing, and its extraordinary climactic scene will suffer greatly from being seen on a video screen.

The Wire provides another example of a phenomenon which David discussed in relation to Paul Greengrass’ United 93: our inability to wholly suppress a feeling of suspense even when we know the outcome of an event. Simply seeing Petit on the wire high above the ground to some extent creates an involuntary state of tension.