Archive for November 2015

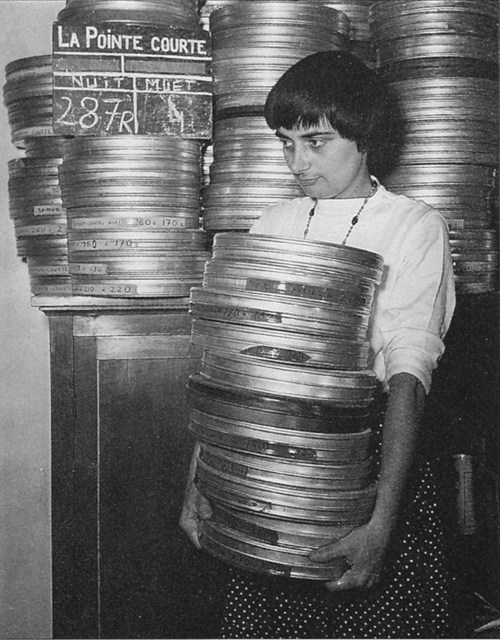

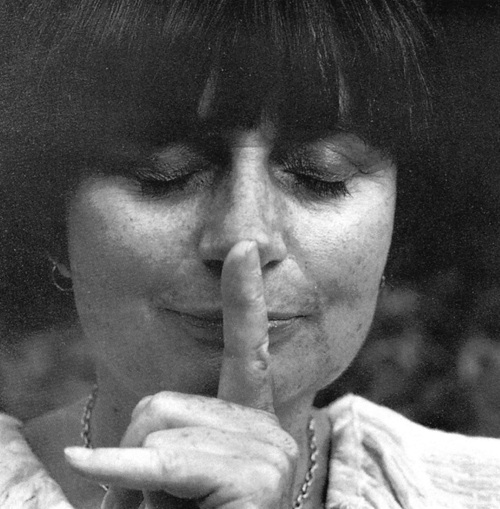

Still Agnès

Self-portrait by Agnès Varda.

DB here:

Sixty years ago, a twentysomething photographer released a film shot in an out-of-the-way French fishing village. Coming right after Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy and Fellini’s La Strada (both 1954), the result announced something new in cinema. Like those other works, it looked forward to the French Nouvelle Vague and the cinematic modernism of Antonioni, Bergman, and a host of other filmmakers.

But the status of Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1955) became apparent only with the most distant hindsight. It didn’t win big attention on the festival circuit, in the international market, or in the pages of highbrow film magazines. Denied a commercial release, La Pointe Courte circulated mostly in French ciné-clubs. In the early 1980s, when I saw it at the Brussels Cinematek, it was still a rarity.

Thirty years after La Pointe Courte, Varda’s career reached a new level. Vagabond (Sans toi ni loi, 1985), widely recognized as her masterpiece, remains one of the great achievements of that modern cinema she helped create. And she hasn’t exactly been idle since. There have been many films both long and short, including a biopic of her husband Jacques Demy in Jacquot de Nantes (1991) and the picaresque The Gleaners and I (2000); the fascinating autobiography Varda par Agnès (1994); and over the last decade a series of installations in museums around the world. She started as a photographer, became a cinéaste, and is now a plasticienne, a maker of painting and sculpture.

She is eighty-seven years old.

Agnès V., not B.

Our colleague Kelley Conway has just published an authoritative consideration of the work of this shrewd, unpredictable survivor. Reading Kelley’s book reminded me of that encounter with La Pointe Courte.

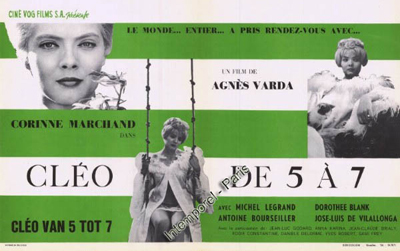

I had known Varda’s more famous works: Cléo from 5 to 7 (1961), screened at my college film society as the project of a New-Wave fellow-traveler; Le Bonheur (1965), which might be called Jules et Jim revisé et corrigé; One Sings the Other Doesn’t (1977), which got circulation among other feminist films of the period. These didn’t prepare me for La Pointe Courte’s daring mix of realism and minimalism. Varda wanted, she said, to make a film that was the equivalent of a difficult book, and for me she succeeded.

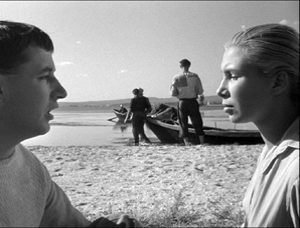

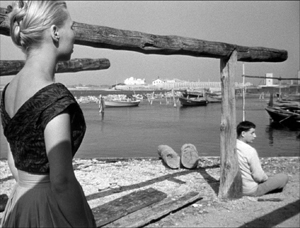

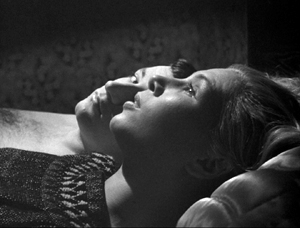

The film alternates sunny images of local life—fishing, net-mending, washing-up, a festival—with episodes in which a Parisian couple drift through the village, oddly detached from the life around them. The everyday scenes are shot in documentary style, but with a casual rigor suggesting Cartier-Bresson. Meanwhile, the couple talk in stylized compositions that could only remind me of L’Avventura.

No wonder Picasso was Varda’s favorite painter: she splits up the couple’s faces with cubistic zeal.

The disjunction between the actuality of a location and the abstraction of the couple’s anomie-riddled duet, often heard only as voice-over commentary, looks forward to Hiroshima mon amour. (No wonder: Resnais edited the film.) I barely understood the French, but the film gripped me. It was of great historical interest, and it had its own stubborn vivacity. When Kristin and I planned the first edition of Film History: An Introduction (1994) I made sure it got in. In that year, forty years after it was made, La Pointe Courte was released on VHS.

Things change. Varda is now regarded as a living treasure of world cinema, preserved in excellent Criterion DVD editions, available for streaming on Hulu, and wrapped up in a vast cube, Tout(e) Varda (20 features, 16 shorts). Whatever she does in the future, we can at least take a long-distance measure of her accomplishments.

The dream of many writers on a single director is to cover it all: appreciative study of the films, background on how the films came to be, assessment of their immediate impact and long-range influence. But this breadth of understanding is very hard to achieve. Where are the documents? How do you get the filmmaker to talk?

Kelley has done it. Her book combines film analysis, historical research, and information drawn from Varda’s archives. Kelley can tell us how the films came to be, what Varda wanted to accomplish, and how they were received. To top it off, there’s a new interview with Agnès herself.

Crossing landscapes

Les Demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993): Varda and Deneuve.

With a brisk practicality echoing that of her subject, Kelley has focused her lens tightly. You can’t quarrel with her choices: La Pointe Courte, the early short documentaries, Cléo, Vagabond, The Gleaners, two installations, and The Beaches of Agnès (2008). Her plan of attack is straightforward: scrutinize the film, then work backward to the conditions of production and forward to the film’s reception.The analyses are models of attention to story and style, images and sounds. Kelley pins down what intrigued me about the acting in La Pointe Courte, showing its debt to Brechtian distancing (a big influence on Varda). She goes on to connect the performances to the experiments in “flat” performance we find in Tati and Bresson at the same period. Kelley shows how many of Varda’s artistic strategies, such as whimsical puns and a love of digression, go back to her early documentaries.

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

Another legacy of documentary: Kelley points up how even the fiction films spring from an attention to the specifics of a locale. “Part of Varda’s journey is regularly exploring a chosen region at length, waiting for ideas, emotions, and images to emerge.” That region might be a single Parisian street (L’Opéra-Mouffe, 1958; Daguerréotypes, 1975) or the fourteenth arrondissement (Cleo from 5 to 7). Like La Pointe Courte, Cleo is the story of a walk, this time purportedly played out in actual duration as a beautiful pop singer awaits the results of a test for cancer. Mona, in Vagabond, is another wanderer, and the wintry bleakness of southern France is as central to the action as whatever psychology we can find in her or the people she meets. The Gleaners and I searches out people who stalk the landscape and live off what they can scavenge. With modern cinema from Bicycle Thieves onward, Dwight Macdonald once noted, “The talkies have become the walkies,” but Varda has always embedded her footloose protagonists in the particulars of place.

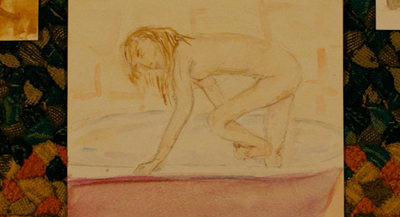

Varda’s personal archive has given Kelley the opportunity to document the director’s creative process. The scripts are sometimes scrapbooks, with texts and images jostling one another. (Kelley offers an example in a 2011 blog entry.) The arrival of digital tools reinforced and expanded Varda’s method of free assembly. Out of a database of images, Varda erected the scaffolding of The Beaches of Agnès before starting her screenplay. She wrote, shot, and edited the whole thing in a nonlinear fashion. During the final stages, two editors worked busily in separate rooms. “I went from one to the other. On one side was Sète and Los Angeles, in the other room was Belgium and Paris.”

As for exhibition, crucial to Varda’s early films was a distinctive French institution. Varda had created her company to make shorts, but when La Pointe Courte grew to 80 minutes, it could not be distributed under those auspices without new investment. As a result, it found its main audience in the network of ciné-clubs that had grown up after World War II. That network became activated to the maximum during the release of Cleo from 5 to 7. One of the side benefits of Kelley’s book is its explanation of the power that the ciné-club scene had achieved by the early 1960s.

Brandishing the slogan “Develop Film Taste, Introduce Masterpieces, Educate the Public,” an astonishing five hundred clubs with over two hundred thousand members showed thousands of films in the year that Cleo was released. Varda took advantage of this situation to promote her film, but Kelley goes beyond the simple marketing issue to point out that the clubs bolstered spectators’ appreciation of New Wave films. She draws on audience comments to show that the organizers guided audiences to talk about form, style, theme, and historical context. The clubs helped create the “demanding viewer” described by Alain Resnais: a viewer eager for challenging films that could bear comparison to advanced works in traditional arts.

Varda’s later films were absorbed into the mainstream commercial distribution/exhibition infrastructure, and Kelley is painstaking in plotting critical response to them. Near the book’s close, she traces how another institution shaped Varda’s work: the museum. Kelley shows how the emerging importance of installation art encouraged filmmakers like Varda and Chris Marker to create multimedia exhibits that were natural continuations of their poetic-essayistic documentaries. The installations seem to have encouraged Varda to take up the autobiographical compilation mode that yielded The Beaches of Agnès.

There is much more in Agnès Varda than I can summarize, but I hope I’ve piqued your interest. For any lover of Varda, Kelley’s book is a must, and even casual viewers will learn things that will drive them to the films. Reading it led me to think about how Varda’s lack of cinephile culture (she emphasizes that she knew nothing of film when she started) allowed her to respond to stories more directly than did the Bad Boys of the Cahiers, who saw everything through a mesh of hundreds of other movies. I was also prodded to think of her as quite an innovator in narrative. She has given us the parallel structure of La Pointe Courte, the fantastic science-fiction plot of Les Créatures, the isoceles love triangle of Le Bonheur, the dual-protagonist structure of One Sings, and the network narrative of Vagabond, with Mona as a circulating object a bit like Bresson’s Balthazar.

From the delightful interview with Lady Potato herself, I allow myself just one spoiler:

KC: You seem to start your projects with considerable preparation but you also have a flair for improvisation. Do you see it that way also?

AV: Yes and no. Or no and yes, depending.

An earlier entry discusses a Kelley talk on La Point Courte. I discuss some ambiguous narrative cues in Vagabond in my updated “Art Cinema” essay in Poetics of Cinema, 166-169.

This has been a good publishing year for our colleagues at Wisconsin–Madison. Lea Jacobs’ book on filmic rhythm came out last winter; go here for our observations.

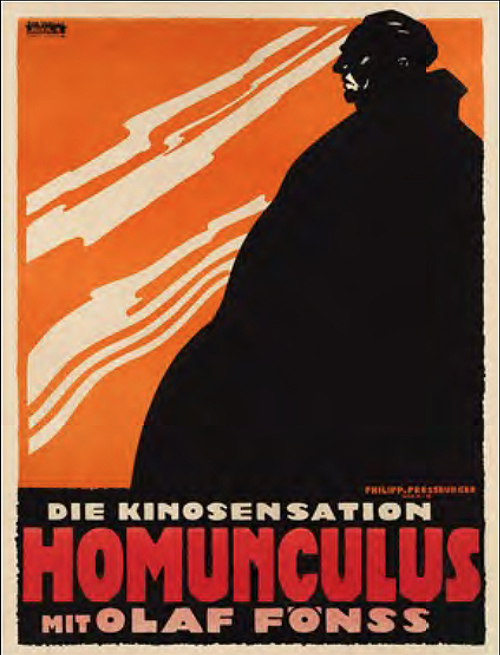

The return of Homunculus

On 21 November, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will be screening a version of Otto Rippert’s long-lost German serial Homunculus (1916). It was reconstructed by Stefan Drössler and his colleagues at the Munich Film Museum on the basis of material from the Moscow Film Archives and other collections. Here’s the background offered by the opening titles on this version.

Homunculus was shown as a six-part series in movie theaters in Germany and its occupied territories in 1916, in the midst of World War I. Each episode was about an hour long. In 1920 the opus was reissued as a three-part version. Scenes were shifted around and new intertitles added.

The following reconstruction adapts the structure of the reissue edition, but it also contains some scenes that had been shortened for the later version and often only survived as photographs.

Fewer than 20% of the original German intertitles have been preserved or are known in their exact wording. Newly worded texts for this reconstruction were based, when possible, on information from contemporary program notes and reviews; also, some were translated back from foreign-language versions of the film and others were created from keywords scratched into the film as montage cues.

For the first time, the current work print makes it possible to recognize the original concept of the entire series.

Today, as a preparation for this very important event, each of us offers you something. First Kristin sketches the trend of fantasy filmmaking in German cinema of the 1910s. After providing this context for the film, David offers some thoughts on this new version of Homunculus and its value for us today.

Kristin here:

The seeds of Expressionism

Many viewers who come to Homunculus for the first time may be expecting traits of the most famous German silent film trend, Expressionism. And indeed historians have mentioned Rippert’s serial, along with Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague, 1913), Hoffmanns Erzählungen (Tales of Hoffman, Richard Oswald, 1916), and others, as forerunners of the Expressionist movement.

But we don’t have a very concrete account of how these earlier films led up to the more famous trend that began with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’s release in early 1920. Moreover, at first glance there aren’t many visual qualities in these earlier films that remind you of Expressionism. They display few or none of those Expressionist distortions of mise-en-scene influenced by contemporary trends in painting and theatre. Similarly, the acting, while exaggerated in a fashion common during the 1910s, seldom reaches the extreme stylization of the performances in Expressionist films.

Yet there are clearly some other similarities between the two groups of films. Most obviously, the early films brought to prominence two related genres to which many of the Expressionist films would belong: the phantastischen film and the Märchenfilm, or fairy-tale film.The main examples of the latter all starred Paul Wegener: Rattenfänger von Hameln (The Pied Piper of Hameln, 1918), Hans Trutz im Schlaraffenland (Hans Trutz in the Land of Cockaigne, 1917), and Rübezahls Hochzeit (Rübezahl’s Wedding, 1916).

For Expressionist filmmakers, elements of the supernatural or the legendary could motivate highly stylized mise-en-scene. In contrast, these 1910s films often used relatively realistic mise-en-scene. Location shooting, straightforward period costumes, and skillfully executed trick photography introduced the fantastic elements into the milieu of a concrete, seemingly everyday world.

A changing view of cinema

Despite such differences, the two genres provide a specific link between some of the most prominent German films of the 1910s and those of the Expressionist movement. Moreover, fantasy films seem to have provided a basis for at least a tentative exploration of theoretical issues surrounding the relationship of cinema to the other arts. In Germany, cinema had previously been compared primarily to literary and theatrical arts, but Wegener’s Der Student von Prag and other films led to a wider consideration of cinema in relation to visual arts such as painting.

In a 1916 lecture, Wegener expressed dissatisfaction with most of what had previously been done with the cinema. He sought to establish the cinema as an independent visual art, separated from theatre and literature:

When a new technology is developed, it is initially cultivated in relation to existing ones, and a new idea does not immediately find its own unique form. The first steamboats looked like big sailing schooners, except that instead of masts they had high funnels. The first railway cars copied mail coaches, the first automobiles kept the large bodies of landaus, and the cinema was like pantomime, drama, or the illustrated novel.

A more broadly based view of the cinema as combining theatrical and graphic arts created a newtradition which carried over from the 1910s to the Expressionist movement of the 1920s. These early films may have become models for the development of an “art cinema” movement in the next decade.

The painterly approach to film promulgated by Wegener lingered in German cinema for about a decade. Starting around 1924, a new approach, based on the moving camera and a more realistic three-dimensional space, would largely replace the older one.

Frames and books

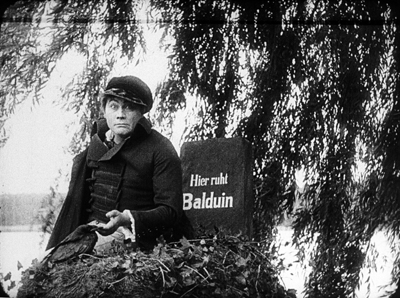

Der Student von Prag.

Aside from this specific link created by Wegener’s emphasis on the pictorial powers of the camera, several conventions of the fantasy films of the 1910s look forward to Expressionism. Perhaps most notable among these devices is the use of the frame story.

Expressionist films frequently employ this device: Francis’ tale to the fellow asylum inmate in Caligari, the record of the Bremen town historian in Nosferatu (as well as the imbedded narratives of the Book of the Vampyres and the ship’s log), the young poet hired to write publicity anecdotes for a sideshow in Wachsfigurenkabinett, and so on.

Yet this pattern was already well established during the 1910s. Der Student von Prag begins and ends with a poetic scroll (“Ich bin kein Gott/bin kein Dämon …”), with the final return leading to a shot of Balduin’s gravestone—upon which sit the Doppelgänger and a crow. (The 1926 remake, which has some distinct Expressionist touches, begins and ends with a gravestone that summarizes Balduin’s life.) Wegener’s other major surviving film from the mid-1910s, Rübezahls Hochzeit, begins with a scene of Wegener, as himself rather than in character as the titular hero, reading to a group of children from a book entitled Rübezahls Hochzeit.

In some cases the frame story introduces multiple embedded narratives. Richard Oswald’s two main fantasy films of the pre-1920 era, Hoffmanns Erzählungen (1916) and Unheimliche Geschichten (Uncanny Stories, 1919), both use this technique. The first begins with a prologue showing Hoffmann surrounded by strange characters like Count Dapertutto and Coppelius. Three dream sequences show him incorporating these figures into bizarre stories; the transition from the prologue to the the main portion of the story begins with Hoffmann in bed as the three sinister figures stand over him.

Unheimlische Geschichten begins, as an intertitle announces, with “A fantastic Prologue at an antiquarian book dealer’s.” On the wall are three large pictures depicting a whore, death, and the devil. After the proprietor chases away his customers and departs, the three images come to life and amuse each other by reading tales out of a book. The series of embedded tales, adapted from Poe, Hoffmann, and other authors of the uncanny, form the bulk of the film.

Not all fantasy films of the 1910s contain frame stories or embedded narratives. Characters do, however, often read or write books that contribute major premises or motifs. In Homunculus, Richard Ortmann keeps a large diary, which records his shifting and somewhat contradictory thoughts, feelings and goals—and thus conveys them to us. Joe May’s Hilde Warren und der Tod (Hilde Warren and Death, 1917) also has no frame story. Its opening, however, involves the heroine reading in a book that death is an escape from sadness. This notion becomes a motif, as the figure of Death appears to her at intervals, foreshadowing her eventual surrender. Books would become an important motivating device in Expressionist films, introducing embedded narratives or crucial motifs.

Hilde Warren und der Tod also carries through the pictorial tradition of Der Student von Prag. Here the special effects are not used to allow one actor to play two roles through split exposure. Rather, superimpositions introduce the figure of Death into the everyday scenes of Hilde’s life.

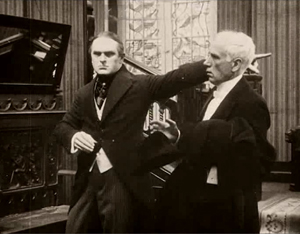

Some early hints of Expressionism

Although the fantasy films of the 1910s don’t contain strongly Expressionist elements, a few stylistic touches foreshadow the distortions of the later movement. Some of these relate to performances by actors who were to become central to the Expressionist movement. In Hoffmanns Erzählungen, for example, Werner Krauss’s stylized acting in the role of Count Dapertutto suggests why he was later cast as Dr. Caligari. Conrad Veidt’s acting and especially his makeup as Death in Unheimliche Geschichten mark him as the ideal candidate to show up in Caligari’s cabinet.

The stylized hand gestures in these two shots are particularly striking, and the same device is carried through in a séance sequence in Unheimliche Geschichten. The lighting of the séance looks forward to more famous scenes in Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), and The Ministry of Fear (1944)—yet here Oswald introduces a twist by including one more hand than there should be for the number of bodies present.

There are other major films made in 1919 which contain stylistic and generic elements soon to become far more prominent. Lang’s Die Spinnen (The Spiders, 1919-1920) draws upon conventions of the thriller serial which would soon by transmogrified in his Expressionist film, Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler. Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (The Puppet) and Die Austernprinzessin (The Oyster Princess), both 1919, could be counted as comic Expressionist films that introduced the style into the cinema months before the appearance of Caligari. The exact cut-off date between pre-Expressionism and Expressionism proper is not vitally important. Some 1910s developments in genre and style prepared the way for Expressionism. Caligari, however great its stylistic challenges were, did not appear in a vacuum.

DB here:

Wanted: Love. #Homunculus

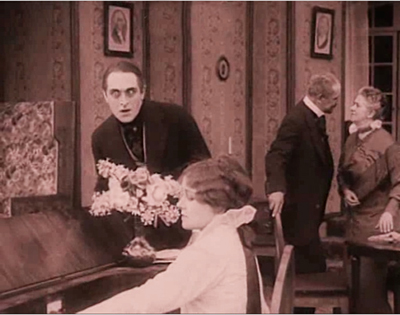

The 1920 reissue of the Homunculus serial compresses its original story considerably, but the outlines are clear. Some omissions in the Munich reconstruction may reflect gaps in the 1920 version. Still, the basic outline of the tale is clear.

Very likely the first test-tube baby, the Homunculus arrives on the scene as the result of a pseudoscientific effort to create life. Out of a bubble, properly zapped, comes an infant.

The baby is brought up in an ordinary human family, thanks to the classic switched-in-the-cradle device. Known as Richard Ortmann, the creature grows up into something of a superman, with extraordinary strength and explosive energy. But his core is hollow. Richard discovers that he lacks fellow-feeling and finds himself alienated from his carousing peers.

When Richard discovers his technological origin, he sets himself a drastic choice: either discover human love or destroy this worthless world.

Each episode replays the same dynamic. Somewhere Richard discovers a possibility of uncorrupted love. But that prospect shatters, either because of prejudice (would you want your daughter to marry a homunculus?) or his sadistic urge to plunge the world into chaos. Only his friendship with Edgar Rodin, one of the scientists who attended his birth, forms an enduring bond across the episodes.

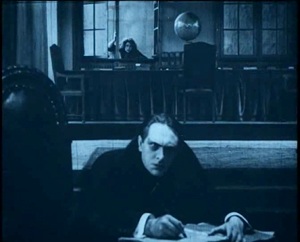

Richard Ortmann plays many roles in his saga. He’s a scientific tinkerer who invents an explosive, a wanderer who ventures into Africa, and a capitalist who enjoys masquerading as a rabble-rouser bent on fomenting rebellion. No sooner has he provoked a war than he tries his own social experiment, that of isolating a young couple in hope of breeding a new society. All these exploits he records in a mighty book

This tome becomes a handy narrative device when the plot demands that other characters learn of his inhuman origins.

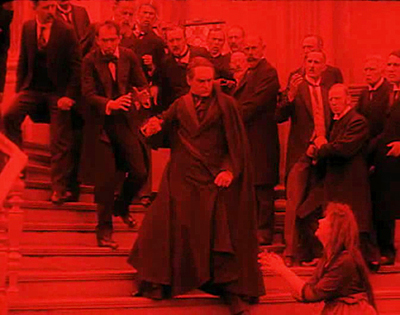

Like those films that clone a Stallone or a Van Damme, the series realizes that one monster can be defeated only by another one. The long tale comes to a climax when Rodin creates a second Homunculus and raises him up to conquer Ortmann–already somewhat weakened from age and fear of death. The titanic confrontation is played out on mountain craigs.

Who will win? Or will both perish?

Annihilation, courtesy Homunculus

The rocking-horse rhythm of the episodes, with hope for Ortmann’s redemption rising and inevitably falling, takes some getting used to. To the filmmakers’ credit, they vary the prospects for love: an array of women, a dog, and in the fourth episode a woman who wholeheartedly embraces Ortmann’s wicked side.

Today’s viewers will also need to accustom themselves to the seething extremes of Olaf Fønss’s performance. Fønss was a major Danish actor who became famous in Atlantis (1913) and who migrated to Germany to star in this series. Fønss conceives his performance as a matter of ferocious glares, raised fists, and heroically villainous postures. It looks overdone to us today.

His box cape, reminiscent of bat wings, helps the brooding effect.

But this isn’t merely a matter of old-fashioned hamming. Fønss’s performance is calibrated to be ragingly different from the other portrayals. Most of the actors exaggerate less, and the pacifist preacher actually underplays. Fønss goes over the top because Homunculus does.

What makes the series compelling? For one thing, it offers a fairly original reworking of the Frankenstein premise. For another, its central conceit of a mad, misunderstood supervillain in search of love can evoke some empathy. There’s also the effort to convey a world in flames, to suggest a cosmic catastrophe with minimal means. While the Great War devastates Europe offscreen, one can hardly avoid thinking of trenches and bombardment in blasted shots like these–which also look forward to the jagged decor of Expressionism.

The student of film technique will, I think, be struck by the filmmakers’ pictorial ambitions. It’s now clear that by focusing just on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) we have limited our sense of the wide-ranging visual discoveries of German cinema. Homunculus belongs with the splendid string of films that includes Der Tunnel (1915), Algol (1920), I.N.R.I. (1920), and the outstanding pair of 1919 films by Robert Reinert, Opium and Nerven. Reinert, unsurprisingly, wrote the screenplay for Homunculus.

The fourth episode, which I commented on back in the summer (based on a much inferior copy), remains a treat for your eyes, with unexpected camera angles and daring use of depth. In the one on the left, we see touches of Expressionist performance in the orchestration of hands.

Elsewhere Kristin has remarked that during the 1910s filmmakers began to go beyond basic storytelling and explore the expressive dimensions of cinema—not only in acting but also in composition, lighting, and set design. The Jugendstil curves of the incubator gleam inside a cavernous chamber you might not expect to find in a lab.

Other episodes provide both grand images—landscapes, sumptuous sets, crowd scenes—and an arresting, small-scale play of light and shade. A purely expository shot of Ortmann approaching Steffens’ study becomes a little suite of shadow patterns, stressed when Ortmann pauses and swivels to the camera and creates a pictorial climax.

Seeing the three-dimensional lighting effects of German cinema of the mid-1910s onward, I wonder whether Caligari‘s jutting, broken-up planes and painted shadows are not only a borrowing from Expressionist painting but also a reaction against the rich volumes created by directors like Rippert.

In all, Stefan Drössler and all the archives and individuals working with him have done world film culture a great service. As with Gance’s Napoleon and Lang’s Metropolis, more footage may appear and need to be integrated into this version. Perhaps some day we’ll have something approaching the full scope of the original series. For now, we should be thankful that another silent classic steps out of the shadows and forces us to rethink what we thought we knew about the history of cinema.

Many thanks to Stefan Drössler for his assistance in preparing this entry.

At Nitrateville Arndt has posted helpful synopses of all six parts of the restoration. Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel (Amsterdam University Press, 1996), pp. 160-167. Excerpts can be found here.

Kristin’s discussion of fantasy films is excerpted from her essay “Im Anfang War…: Some Links between German Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” in Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Bibliotexa dell’Immagine, 1990), 138-161. The Wegener quotation is from Paul Wegener, “Die künsterlischen Möglichkeiten des Films,” in Kai Möller, ed., Paul Wegener: Sein Leben und seine Rollen (Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag, 1954), p. 102. Translation by KT.

Elsewhere on this site we discuss other neglected German films of the period: Der Stoltz der Firma (The Pride of the Firm, 1914); Der Tunnel (1915); Asta Nielsen features of the teens; Doktor Satansohn (1916); Hilde Warren und der Tod (1917); Die Pest in Florenz (The Plague in Florence, 1919, directed by Rippert after Homunculus); late-1910s Lubitsch; Algol and I. N.R.I. (both 1920); and Der Golem (1920). I have an essay on Robert Reinert’s remarkable films in Poetics of Cinema. Some day I hope to write more about Paul Leni’s war drama Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, 1917) and Joe May’s energetic and entertaining serial Die Herrin der Welt (Mistress of the World, 1919).

Deadlier than the male (novelist)

DB here:

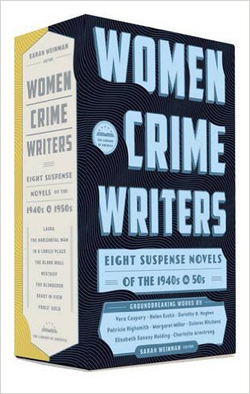

It’s about time! Sarah Weinman, editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives (already praised in these precincts) has brought out a two-volume set devoted to women crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s.

It’s not that these authors are utterly unknown. Popular in their day, some retained a following for a few decades, and Patricia Highsmith has become an enduring figure. Yet the never-ending frenzy for male-oriented noir in books and movies has led us to neglect what these writers and their peers accomplished. In the online essay “Murder Culture” I argued that we’ve probably overemphasized the hardboiled detectives and brutalized losers, and we’ve not paid enough attention to the accomplishments of other writers. The rise of the psychological thriller was central to 1940s popular culture.

Granted, it wasn’t only gynocentric. The thriller assumed exciting shapes in the hands of talented men like Patrick Hamilton, Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin. But the 1940s saw the emergence of a powerful cadre of women writers, many of whom started writing “pure” stories of detection but decided that suspense would be their forte. Surely they were encouraged by the success of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, the best-selling mystery novel before Mickey Spillane came on the scene. But these suspense-mongers avoided mimicking Mignon Eberhart and other predecessors in the innocent-girl-in-a-spooky-house tradition. These new talents saw menace crouching behind the windows of drab houses and apartment blocks. Out of several tendencies I tried to sketch in that essay, they forged a tradition of what Weinman calls “domestic suspense.”

The Library of America volumes give us a fine occasion for appreciating what they accomplished.

Artisans of suspense

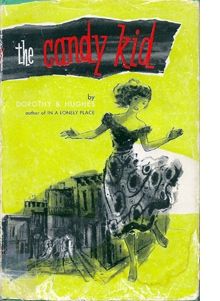

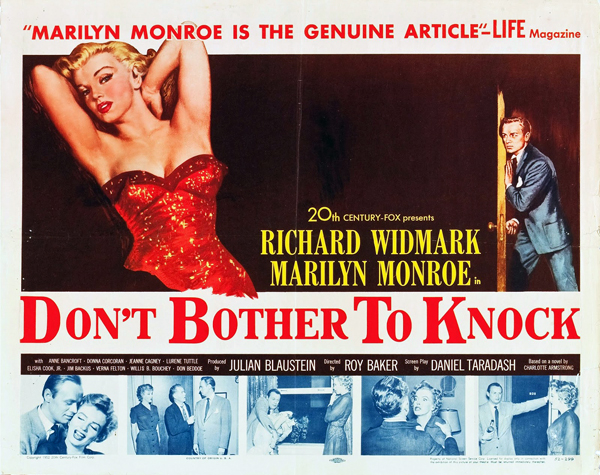

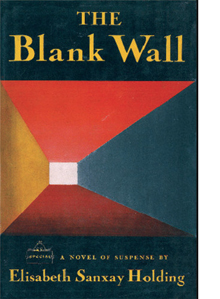

You might say that Double Indemnity and Out of the Past are quintessentially 1940s-1950s films, and I’d agree. But other important films were derived from works by women writers. The list of Highsmith adaptations, starting with Strangers on a Train (1951), is too long to recite here, but let’s remember that Charlotte Armstrong provided source novels for The Unsuspected (1947) and Don’t Bother to Knock (1952, from Mischief), as well as for Chabrol’s La Rupture (1970) and Merci pour le Chocolat (2000). Filmmakers produced now-classic versions of the Dorothy B. Hughes novels The Fallen Sparrow (1942), Ride the Pink Horse (1946), and In a Lonely Place (1950). The prolific but less famous Elizabeth Sanxay Holding gave us The Blank Wall (1947), adapted twice (The Reckless Moment, 1949, and The Deep End, 2001). Dolores Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold (1958) yielded the implausible basis for Godard’s Band à part (1964). Helen Eustis’s The Fool Killer (1954) became a 1965 film. And of course Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) became a monument of studio moviemaking.

The thriller, you could argue, makes more engaging cinema than the straight detective story. Much as I admire cinematic sleuths like Sherlock Holmes, Nick Charles, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and particularly Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, pure mystery plots need a lot of bells and whistles to keep from being simply a matter of following the detective as he moves from place to place asking questions and dodging blows on the head. The 1940s tales of espionage, women in peril, serial killings, household anxieties, warped husbands and crazy wives and guileless governesses and all the rest have left a stronger legacy today. We live in the Age of the Thriller, as a glance at any bestseller list will indicate. The recent death of Ruth Rendell, arguably Highsmith’s only top-flight competitor, can only remind us of how the genre has flourished for decades.

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

The Library of America collection has rounded up several contemporary purveyors of suspense to write brief online appreciations of the titles in the collection. These are well worth reading. On each page further links take you to fresh material. There’s also a succinct introduction by Weinman. The print editions include her judicious career summaries, as well as notes on allusions and citations in each novel.

For readers interested in how women’s cultural roles are represented in fiction, these books provide a field day. Several of the professional commentaries suggest that the authors injected social criticism into their works. These writers are far more willing to get inside men’s heads than the hard-boiled boys are to think like a woman, so you can see the macho attitude in a new light. Here’s how Dorothy B. Hughes in The Candy Kid (1950, not in this collection) describes her hero:

Just as he was thinking that he’d better go in and buy a pack, wait for Beach in the air-cooled coffee shop, the girl came around the corner. She was tall, almost as tall as he, but he took a quick look at the pavement and saw that she was propped on heels. That made him feel more male.

Very often these writers take certain stereotypes, both male and female, and submit them to pressure through their craft. Others seem to accept those stereotypes and employ them for their own storytelling ends. Those ends are very much worth our attention.

We know that several of these writers were self-conscious artisans. Hughes and Armstrong wrote articles reflecting on mystery and suspense, while Hughes also wrote a sharp biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. Hughes also conducted a course on mystery writing at UCLA in the 1960s; she invited Vera Caspary in for a guest lecture, and Caspary’s advice makes for fascinating reading. Highsmith’s notebooks, preserved at the Archives littéraires in Switzerland, are filled with meditations on story problems, and she wrote as well a book-length manual, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966, 1981). I don’t think that any hard-boiled writers of the era have left such systematic reflections on the nuts and bolts of their work.

Once we pay attention to technique, we can see how these writers rework topics and concerns of the day. For example, we could talk a long time about how social roles induce women to assume a split identity: one face for friends and family, another that resists the masquerade. But these, after all, are mysteries, so that divided identity has to be dramatized—or better yet, played with and teased out for the sake of suspense and surprise. It’s remarkable that two of the books in the collection exploit the syndrome of Multiple Personality Disorder, which becomes part of the final surprise. Another, Laura, makes an enigma of the woman’s inner life by virtue of dispersed viewpoints.

If we want to learn about storytelling, we can usefully look at how writers manage traditional demands of craft. These books “say what they say” in and through technique—narrative form, literary style. The experience that results can be an enduring achievement.

Pronoun trouble

No use asking if the crime writer has anything of the criminal in him. He perpetuates little hoaxes, lies and crimes every time he writes a book.

Patricia Highsmith

Start with style—important in all storytelling, but posing some fascinating issues in the domestic thriller.

One problem faced by all these writers was: How to avoid the sentimental style of romantic suspense writers? Here’s a typical passage from Mignon G. Eberhart’s Another Woman’s House (1946).

She said, blindly choosing trite and inadequate words, “You cannot change your own sense of loyalty, of your own creed and code. It’s bred in your bone; it’s part of your body.”

He understood all the argument below it. He understood too that it was a fundamental argument in his own heart. His eyes deepened, searching her own. He said suddenly, “Myra, you must see this sensibly; you must be realistic and . . .”

“Oh, Richard, Richard!” She cried despairing, and put her head against his shoulder.

There’s some of this novelettishness in Armstrong, as in this bit from Mischief:

When a fresh scream rose up, out there in the other room in another world, Ruth’s fingertips did not leave off stroking into shape the little mouth that the wicked gag had left so queer and crooked.

Hughes and Hitchens, I think, leaned toward the hardboiled laconicism of Hammett and Cain, though without the slanginess. In The Horizontal Man, Eustis tries for a brittle, satiric tenor and some Hollywoodish banter between a reporter and a college woman. Highsmith was adamant in refusing what she called a “pulp” style. Hence her flat, spare simplicity. (Funny, though, since she started out writing comic books for the company that would become Marvel.)

Stylistic options can lie very far down. For years I’ve been curious about what fiction writers call their characters on first entrance. It’s a fundamental creative choice, and it’s absolutely forced: you have to call them something. And what you call them matters.

Here’s the beginning of Armstrong’s Mischief:

A Mr. Peter O. Jones, the editor and publisher of the Brennerton Star-Gazette, was standing in a bathroom in a hotel in New York City, scrubbing his nails. Through the open door, his wife, Ruth, saw his naked neck stiffen….

Cozy, our relation to this Mr. and Mrs. Jones: Mischief gives their first and last names. So far, no reason to be apprehensive. But here’s the start of Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold:

The first time they drove by the house Eddie was so scared he ducked his head down. Skip laughed at him.

Here a relationship is defined through laconic action: we’re on a first-name basis with the pair. It’s as if we’re riding in the back seat.  Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

The man in the dark blue slacks and a forest green sportshirt waited impatiently in the line.

The girl in the ticket booth was stupid, he thought, never had been able to make change fast.

Highsmith is more ominous: No names, just a man as if seen from across the sidewalk. Yet we can’t say the presentation is “objective” because we’re given his annoyed thoughts about the ticket girl. So we are forced to ask: If I’m in his head, why don’t I know who he is? And why is he in a hurry?

And finally, the opening lines of Eustis’ The Horizontal Man:

The firelight played over all the decent, familiar objects of his everyday life; he viewed them desperately, looking for some symbol of succor. The firelight played on his rolling eyeballs, the careless tendrils of his black hair. “Oh now,” he said, “Oh now, I say, look here…” trying to summon a tone of commonplace to breast the tide of nightmare that was rising in that room.

Eustis dispenses with everything but he in describing something terrible going on. Not only do we not know who’s suffering, but we won’t know for some time. This, like the Highsmith, might be called “pronominal mystery”: not knowing anything about who’s in danger, we sense the danger as a pure force swallowing up trivialities of identity.

Most manuals of fiction-writing start by reviewing the bigger choices, like first- or third-person narration, but note that even within third-person storytelling, these passages bristle with different implications. Each of these openings puts us in a different relation to the characters picked out.

The storyteller makes a choice about how to name the actors in the scene, and that choice leads to others: the scene is built out the premises of what have launched it. Ruth, who studies her husband Peter at the mirror, will become one conduit of information within Mischief. Skip, who laughs at Eddie as they size up the home they’ll invade, will bully his partner throughout Fools’ Gold. The man in the slacks and sportshirt will drop out of The Blunderer for several chapters. So no need to name him yet; magnify the mystery. And the opening scene of The Horizontal Man will continue with personal but untagged pronouns—a she will be picked out too—as the full awfulness of the action emerges.

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

Fussy as these details are, they’re what I mean by craft. The verbal texture of any piece of fiction depends on dozens of such minute judgments. Just as in film every cut, camera movement, and actor’s glance matters, so does every word in a prose narrative. These writers understood that what we learn, syllable by syllable, can be a potent source of uncertainty and suspense.

Who sees and who knows?

The whole intricate question of method, in the craft of fiction, I take to be governed by the question of the point of view—the question of the relation in which the narrator stands to the story.

Percy Lubbock, The Craft of Fiction

In mystery fiction, management of point of view is critical. Not only will it weave the moment-by-moment verbal tissue, but it provides the large-scale parts that present the overall action. Where the Had-I-But-Known romance tends to be restricted to a single character, often through first-person narration, domestic suspense employs other options. It’s significant that of these eight novels, only one, Laura, employs first-person narration, and that in a distinctive way I’ll consider further along.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

How to complicate this basic situation? Armstrong recruits a device—call it a narrative meme if you want—that emerges at the period: the eyewitness, typically in an urban setting, who glimpses possibly criminal doings and gets involved. This device finds its supreme filmic expression in Rear Window (1954), but it’s established in earlier films like Lady on a Train (1945), Shock (1946), and The Window (1949), and in the radio drama The Thing in the Window (1945), by Lucille Fletcher (another thriller queen, but of the airwaves). In Mischief, people in a building across the street from the hotel intervene in the doings of the babysitter, and the plot “intercuts” all their trajectories in order to create tension.

Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold similarly jumps from character to character, even within a single scene. This tale of a heist that is way above the skill sets of the thieves—a sort of humorless anticipation of an Elmore Leonard or Donald Westlake situation—uses unrestricted narration to build sympathy for the characters who are gulled into participating.

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Skip listened, at first with indifference. He’d heard already from Eddie of Karen’s reaction to the money, her frightened excitement about it. It took a moment to realize that this wasn’t more of the same, the reaction of an inexperienced girl, but that a bad break had really occurred.

Throughout the chapter, this rather nineteenth-century version of omniscience will toggle between Karen and Skip, heightening the disparity between her lack of awareness and his harshness. “He was just having fun though she didn’t know it.” Arguably, a heist plot needs a certain wide-ranging narration (see The Asphalt Jungle), but Hitchens uses it to take us into the minds of all the characters, major and minor, and suggest both vulnerability and menace.

In a classic detective story, the identity of the culprit is concealed until the end. One Golden Age “rule” is that in the course of the action we must never be given the viewpoint of the killer. The rule was broken on occasion, notably in a certain novel by Agatha Christie, but it remained rather firm. In the thriller, by contrast, we can be in the killer’s mind, knowing full well that he or she is indeed the killer. A prototype is Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square (1941). Two books in this collection walk a line between detective story and thriller in this respect.

In Eustis’ The Horizontal Man, a popular professor has been murdered. The effects of his death ripple out across the campus, and the narration shifts among his colleagues, some students, and a reporter investigating the crime. In the midst of a corrosive satire of the academic life, we suspect that someone whose mind we have entered will turn out to be the culprit. So we have to probe the inner lives of the characters we encounter for psychological clues, not physical ones. The author must conceal the killer’s identity and “play fair,” in that what we learn at the end unexpectedly fits the characters’ stream-of-consciousness musings.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

It is a pity that this edition didn’t include Millar’s 1983 Introduction and Afterward. The latter explains the origin of the book’s device, while the Introduction reports the effects the book had:

I was threatened with a libel suit, informed by a patient in a mental institution that at last she had found someone who really understood her, invited to join a coven of witches, asked to address a meeting of psychiatric social workers, and presented with the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allan Poe award for best mystery of the year.

At the other extreme, two of these novels focus on extremely restricted viewpoints. Hughes’ In a Lonely Place is wholly locked within the mind of a hypermasculine ex-Air Force pilot who trails and murders women. Hughes gives us the pronominal tease: it’s he for the first five pages until, when he places a phone call, we learn he’s called Dix Steele. In a cat-and-mouse game reminiscent of films like Woman in the Window and Where the Sidewalk Ends, the killer gets close to the murder investigation. Dix’s army buddy is the chief cop on the case, so Dix can monitor things and even drop in on crime scenes. Strikingly, Hughes puts the killings “off-page.” This admirably eliminates any Spillane-ish sensationalism while keeping the focus wholly on the way Dix loses control of his masquerade. He’s worn away in a series of confrontations with two women who see, as no man can, something deeply wrong in him.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

As you’d expect, Highsmith tries something more intricate in The Blunderer. Here we have two protagonists, each man given his own viewpoint. But after an opening introducing us to one man’s crime (in a scene that spares no violent detail), he drops out of the action for a hundred pages. We concentrate instead on the polished professional lawyer whose life unravels when his domestic skirmishes—nearly all petty and drab—come to a head. As with most Highsmith men, he is tempted to do something very trivial and very stupid, almost out of intellectual curiosity. Highsmith policemen take a dim view of such enacted thought experiments.

As the two protagonists’ worlds converge, we get the characteristic Highsmith themes of self-possessed men losing their nerve, the traps of respectable life, the risk of impulsive action, the ways in which friends turn away from you when they suspect you of lying. The lawyer is called by his first name, Walter, while his counterpart is known to us by his last name, Kimmel. In such subtle ways does an author align us a little more closely with one character than another. Both, though, are blunderers.

I should add that all the markers of 1940s fiction and film—dreams, hallucinations, false fronts, unstable families, untrustworthy lovers, socially adroit psychopaths—are woven into these novels with great skill. What more could you ask?

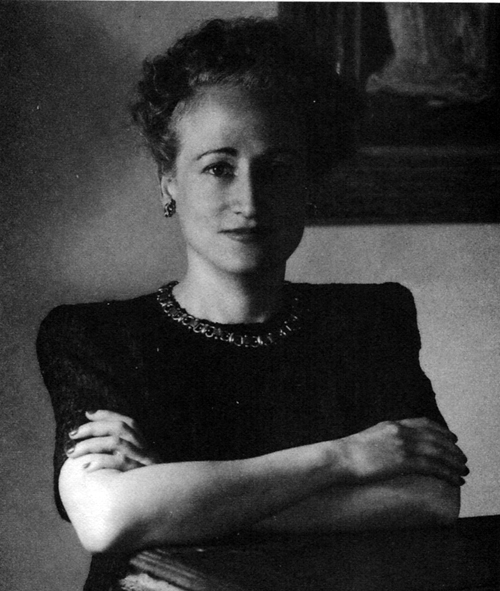

A frenzy of recapitulation

Vera Caspary, 1946.

The earliest novel in Weinman’s collection is also one of the most remarkable of the period. Vera Caspary was a woman to be reckoned with—Greenwich Village free-love practitioner, Communist party member, occasional screenwriter, boundlessly energetic purveyor of suspense fiction, passionate paramour of a married man, and advocate for women in prison. Our State Historical Society holds her personal collection, which includes fascinating notes on projects both realized and unrealized. Turning the pages of her files, you meet a crisp, professional artisan.

So let’s look at Laura the novel. If you know the film, as you probably do, nothing I say will spoil the book for you.

In 1942 Collier’s (“The National Weekly”) offered Caspary $10,000 for the serial rights to Ring Twice for Laura. That sum, equal to $150,000 today, didn’t include book publishing rights, movie rights, and any other ancillaries. The price tag tells us quite a bit about the robust slick-magazine market of the period and about Vera Caspary’s standing. After writing novels, plays, short stories, and screenplays, she was no novice, but her new manuscript set her on a path toward fame. Published as Laura in 1943, it found acclaim as “something quite different from the run-of-the-mill detective story.” The publisher called it a “psychothriller.”

Laura is both a mystery story and a romance. A woman is found murdered in her apartment. Although a shotgun blast has disfigured her face, she’s initially identified as ad executive Laura Hunt. After the funeral, while detective Lieutenant Mark McPherson is poking around her apartment, Laura returns from a trip and it’s revealed that the victim was actually Diane Redfern, a model to whom Laura had loaned the apartment.

The misidentified-victim convention triggers an investigation into the usual sort of suppressed backstory: How did Diane wind up in Laura’s place? Was she alone? Was she the target all along, or was she mistaken by the killer for Laura? Along the way, the cop—already half in love with Laura dead—begins to both woo and browbeat her.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

What was striking about the book was its point-of-view structure. “Four persons tell this story and play the leading parts in it,” noted the New York Times reviewer. “McPherson questions all three, and all three tell him lies.” In presentation Caspary revived what has been called the casebook method of composition: a series of testimonies, written or transcribed from speech, that recount the mystery. Sometimes those are accompanied by police reports, newspaper coverage, and other documents.

The method is identified with Wilkie Collins’ two great novels The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868), and was taken up occasionally by others, particularly within a trial situation (e.g., The Bellamy Trial, 1929). Before Laura, probably the most famous instance of a mystery collation is Dorothy Sayers and Robert Eustace’s Documents in the Case (1930). The technique also has affinities with multiple-viewpoint assembly in “straight” fiction influenced by Dos Passos; Kenneth Fearing had tried it in his experimental novels The Hospital (1939) and Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) as well as in his crime stories Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946).

To take us through the eight days of the investigation, Caspary’s casebook assigns each character a block of narration. Each block, told in first person, has its own distinctive tenor, representing a particular subgenre of mystery fiction.

If you didn’t know the Laura mystique already, you might suspect that the opening chunk, told from Waldo’s perspective, would announce him as the brilliant amateur detective who will solve the case and surpass the plodding McPherson. Waldo is a celebrity columnist, a connoisseur of murder and lethal banter. Like 1920s detective Philo Vance, he collects art and lords it over others through aggressive erudition. Waldo writes in periodic sentences of eloquent self-congratulation:

My grief in her sudden and violent death found consolation in the thought that my friend, had she lived to a ripe old age, would have passed into oblivion, whereas the violence of her passing and the genius of her admirer gave her a fair chance at immortality.

There are even the sort of fake footnotes that we find in S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen novels of the 1930s, attesting to the scholarly bona fides of this dilettante sleuth.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

That is my omniscient role. As narrator and interpreter, I shall describe scenes which I never saw and record dialogues which I did not hear. For this impudence I offer no excuse. I am an artist, and it is my business to re-create movement precisely as I create mood. I know these people, their voices ring in my ears, and I need only close my eyes and see characteristic gestures. My written dialogue will have more clarity, compactness, and essence of character than their spoken lines, for I am able to edit while I write, whereas they carried on their conversation in a loose and pointless fashion with no sense of form or crisis in the building of their scenes.

This is an extraordinary passage. It opens the very-‘40s possibility that what follows may be Waldo’s fantasy. Only near the end of his text does Waldo assert that his knowledge of McPherson’s investigation is derived from what Mark later told him one night at dinner. We will soon learn that Waldo’s opening section was written directly after that dinner, but he actually didn’t know one key fact. His omniscience is an illusion.

McPherson takes up the tale in the second part. He has read Waldo’s account and treats it as a separate piece of evidence. As we follow McPherson’s investigation, we’re in the realm of the police procedural. The register shifts too. If Waldo’s style is showoffish, McPherson’s is laconic. Whereas Waldo celebrates how his prose will immortalize Laura, McPherson admits that his version of things “won’t have the smooth professional touch.”

Actually, though, it does. It reads hard-boiled.

As we stepped out of the restaurant, the heat hit us like a blast from a furnace. The air was dead. Not a shirt-tail moved on the washlines of McDougal Street. The town smelled like rotten eggs. A thunderstorm was rolling in.

Caspary gives us the voice of the tough but vulnerable cop, the voice we would later learn to call noir. There’s an echo of James M. Cain when McPherson signals that in retrospect he was wrong to trust this femme fatale: he sourly describes himself in the third person.

She offered her hand.

The sucker took it and believed her.

McPherson’s eventual victory over Waldo is prefigured in the cop’s reflections on writing up crime. When Waldo learned Laura was still alive, McPherson says, “The prose style was knocked right out of him.” So much for Wimseyish fops set down in a Manhattan murder.

Shelby gets his voice in as well. A brief third section consists of a police transcript of McPherson’s questioning. Aided by his attorney, Shelby withdraws some lies, dodges uncomfortable areas, and generally remains the most obvious suspect—as well as Mark’s rival for Laura. At this point in the book Caspary begins to play an intricate game of knowledge, in which we get, piecemeal, information that tests the string of deceptions and evasions confronting McPherson.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

It’s always when I start on a long journey or meet an exciting man or take a new job that I must sit for hours in a frenzy of recapitulation.

Now the action is that of the woman in peril, the figure familiar from Eberhart and Rinehart and Sanxay Holding. And so the stylistic register is “feminine,” tracking fluctuations of feeling and noting costume details and shades of color. Laura’s narration is also suspenseful and contemplative, dwelling on moments that seem to radiate danger—McPherson’s trick questions, Waldo’s sinister manipulations, and Shelby’s pretense that he’s protecting her rather than himself.

The emphasis is less on external behavior than Laura’s growing realization of why she has clung to two failed men. She will gradually realize that McPherson, despite his coldness, is the best match for her. Waldo is “an old lady” and Shelby is an overgrown baby. Caspary the left-winger gives these portraits the taint of class corruption. Waldo and Shelby are ghoulish creatures of the high life, while Aunt Susie is the faded, self-indulgent beauty Laura might become.

Laura’s recognition of her entrapment is rendered in a choppy, spasmodic fashion. Waldo’s, McPherson’s, and Shelby’s accounts have all been linear. Laura’s is not. It skips around in time, replays scenes we’ve seen from other viewpoints, and incorporates dreams that seem as well to be flashbacks.

This is no way to write the story. I should be simple and coherent, fact after fact, giving order to the chaos of my mind. . . . But tonight writing thickens the dust. Now that Shelby has turned against me and Mark shown the nature of his trickery, I am afraid of facts in orderly sequence.

In a narrative dynamic we find throughout 1940s fiction and film, the strong career woman is thrown off balance and succumbs to confusion. The most notorious example is of course Lady in the Dark, the 1941 play that appeared on film in 1944, the same year as the film version of Laura.

The lady returned from the dead will need a real man to rescue her. That rescue is enacted, again, in prose when McPherson reassumes control of the narrative. The book’s fifth part consists of two sections: the classic summing up and denunciation of the culprit (Waldo) and the rescue of Laura from Waldo’s second attempt to kill her. McPherson’s hard-boiled diction has won out. As Waldo is taken away in the ambulance, however, he earns a degree of purely verbal revenge. McPherson’s narration quotes Waldo’s mumbled phrases as, dying, he fills in plot points. In the process, his style gets inserted, like an alien bacterium, into McPherson’s curt passages.

McPherson, who can afford to be gallant, gives Waldo the last convoluted word. It comes in a quotation from the manuscript found by McPherson at the climax, a passage that confirmed Waldo’s guilt. In Waldo’s unfinished account, Laura is an essence of womanhood, a modern Eve; but one who continually reminded him that he could never be Adam.

During production of the film version of Laura, the makers considered mimicking the novel’s block construction. Citizen Kane had made multiple-viewpoint narration more thinkable in the 1940s. In the end, though, only Waldo’s voice-over was retained, with results that have provoked several critical comments.

The film made many other changes, large and small, but during this reading of the novel two improvements stood out for me. Making Waldo a radio commentator as well as a columnist allows a rich play of sound that comes to a climax at the film’s dénouement. Secondly, Waldo drops out of the book for many stretches, largely because Caspary is concerned to throw suspicion on Shelby and Laura. But the film keeps Waldo onscreen a lot, even permitting him (against all plausibility) to tag along with McPherson on the investigation. His waspish interjections, delivered by a suave Clifton Webb, add a nice tang, while sustaining Caspary’s theme of class snobbery. The film adds several kinks, such as introducing Waldo writing in his bathtub. The situation includes one of those how-did-they-get-away-with-it? moments when, as Waldo climbs out of the water, Mark glances scornfully offscreen at Waldo’s privates.

Caspary would go on to other successes, notably the screenplays for A Letter to Three Wives (1948) and Les Girls (1957) and several other novels that play with block construction and shifting viewpoints. But Laura would remain her prime achievement. It’s a striking novel that became a landmark film and an enduring example of how female crime novelists could stretch and deepen the conventions of popular literature.

A useful and spoiler-free biographical survey of many of these writers is Jeffrey Marks’ Atomic Renaissance: Women Mystery Writers of the 1940s and 1950s (Delphi, 2003). See Mike Grost’s inevitably encyclopedic coverage as well.

Highsmith’s disdain for pulpish style is discussed in Andrew Wilson, Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith (Bloomsbury, 2003), p. 124; my quotation above comes from p. 256. I’m grateful to Ms. Stéphanie Cudré-Mauroux of the Archives littéraires suisses for other information about Highsmith.

Some craft advice from these authors can be found in Dorothy B. Hughes, “The Challenge of Mystery Fiction,” The Writer 60, 5 (May 1947), 177-179; Charlotte Armstrong, “Razzle Dazzle,” The Writer 66, 1 (January 1953), 3-5; and Patricia Highsmith, “Suspense in Fiction,” The Writer 67, 12 (December 1954), 403-406. Millar’s discussion of Beast in View is in the International Polygonics edition of the novel, 1983, pp. 1-2, 249.

Vera Caspary’s autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979), is a captivating read that introduces us to a fascinating personality. (“Under the ready smiles were witches’ grimaces, beneath the padded bra a calcified heart.”) In Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011) A. B. Emrys offers an excellent study of Caspary’s work in relation to mystery traditions. Caspary’s “official” response to Preminger’s film comes in “My Laura and Otto’s,” Saturday Review (26 June 1971), 36-37.

Hammett was no slouch at juggling proper names and pronouns either. I marvel that he could call Ned Beaumont “Ned Beaumont” all the way through The Glass Key. All the other characters are tagged with their first or last name, but this option maintains an unsettling middle distance on his psychologically opaque protagonist.

I discuss Waldo’s narration in the film version of Laura in more detail in this entry.

Wesworld

DB here:

Wes Anderson is back on our blog.

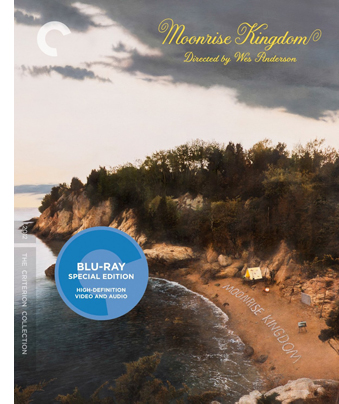

I composed a 2007 entry that tried to trace the stylistic tradition he belongs to (sloganized as “planimetric” staging and “compass-point editing”?). In 2014 the multiple aspect ratios of The Grand Budapest Hotel grabbed my attention. That essay, revised, was included in Matt Zoller Seitz’s anthology on the film, duly teased and announced here. At greatest length, another 2014 entry offered some thoughts on Anderson’s standing as an auteur through an analysis of Moonrise Kingdom (2012).

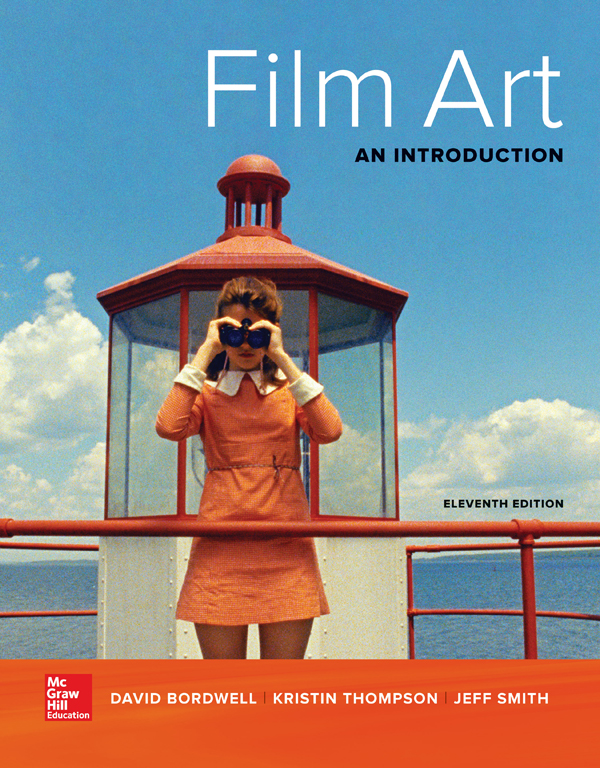

The film has worked its way into the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming in January. In Chapter 11 an analysis of Moonrise Kingdom joins discussions of films by Ozu, Hawks, Hitchcock, Vertov, Scorsese, and other major directors. Moonrise Kingdom, I think, a film that will have lasting interest for young viewers and filmmakers, and it’s a fine vehicle for teaching principles of narrative and style.

Since then I’ve learned more, thought more, and seen more. Specifically, I’ve seen Moonrise Kingdom in the gorgeous new Criterion Blu-ray release.

Since then I’ve learned more, thought more, and seen more. Specifically, I’ve seen Moonrise Kingdom in the gorgeous new Criterion Blu-ray release.

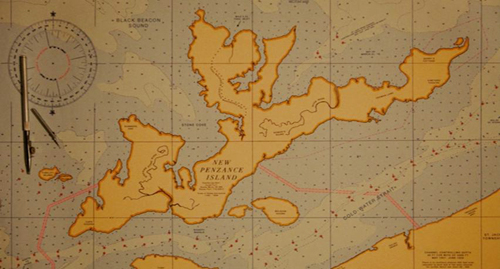

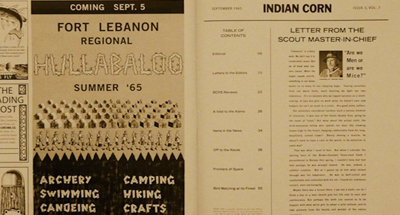

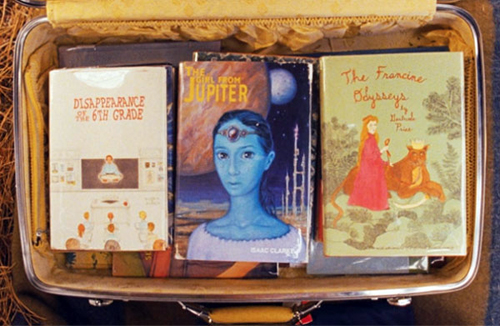

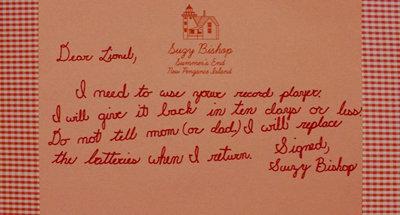

That release bundles in the sort of auteur artifacts my blog entry talked about. The purchaser gets a map of New Penzance, an invitation to the 1964 Noye’s Fludde performance at St. Jack’s, rather unflattering snapshots of the characters, and a postcard of the island ensemble (minus Social Services and the phone operator). On the disc we get Edward Norton home movies (as casual as anybody else’s, but showing some ingratiating behind-the-scenes stuff), some Bill Murray riffs, a brief making-of, and other snippets. The booklet, modeled on the Scouts’ magazine Indian Corn, includes a brief, sympathetic essay by Geoffrey O’Brien and reviews by kids.

A kid also conducts, if that’s the word, the extremely free-form commentary track on the disc. Young actor Jake Ryan, who plays one of Suzy Bishop’s brothers, sort of oversees chat among Anderson, Criterion leader Peter Becker, and participants in the production. Those last are brought in via phone calls. There are bathroom breaks, discussions of San Francisco Chinese restaurants, a Mozart piano performance by Jake, and a moment in which one discussant is accused, doubtless unjustly, of falling asleep. The whole enterprise, cut down from a five-hour marathon, will probably enchant Anderson devotees while giving new ammunition to those who find those admirers nuts, or worse. For my part, I found that Edward Norton and Bill Murray shared some worthwhile bits of acting craft, and Anderson gave some interesting information about the production.

Anderson adepts don’t need me to urge them toward this disc and its accessories. Today I want to think some more about this movie, which after two more viewings hasn’t lost any of its fascination for me. I’ll be concentrating on what it shows about worldmaking on the screen.

Departures, minimal and more

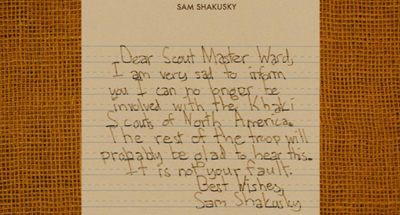

If you stripped off all the enticing elements like the toy lighthouse and the Khaki Scout badges, the gnomelike narrator and the interjected postcards and the implausibly perched treehouse, what do we have? In its bare bones, a pretty simple plot anatomy.

A couple in love, blocked by parental opposition, runs away. After an idyllic day and night, they are captured and separated. Then it all starts again, thanks to the miraculous conversion of some of the boy’s enemies, who decide to help him and the girl escape.

Again the couple flees, this time to be unofficially married. Pursued by parents and the authorities, the couple is trapped in a massive storm and is rescued by the kindly sheriff. They are united to live in a more-or-less tolerated love affair.

Although these are primal patterns of engagement, Moonrise Kingdom wouldn’t claim much interest if this were all it offered, folktale-fashion. As usual in modern narrative, the real interest involves finer-grained plot developments, characterizations, and narrational maneuvers. So the basic anatomy gets flesh, nerves, muscles, and circulating blood. Anderson and co-screenwriter Roman Coppola give us well-defined characters, dramatic situations, and secrets and mysteries and suspense. They play with time and viewpoint, build suspense, trigger surprises, and wrap things up with unexpected neatness. Several of these tactics I tried to chart in the 2014 entry.

Anderson and Coppola could have stopped there, but they didn’t. They went on to invent a world.

You can argue that this world’s main purpose is to distract us from the simple flight/pursuit/capture/rescue dynamic of the basic story action. But I’d argue that the final film benefits from fleshing the core action out in a way that situates it in a unique milieu. There’s also the point that worldmaking is no small achievement. Your task as a storyteller, George Lucas once noted, will change when you have to figure out what your character’s fork looks like.

Take the three dimensions of narrative I sketched out here and here—story world, plot structure, and narration. For some of us (I include myself) genre-based narrative has creative, even experimental possibilities along all those dimensions. Crime fiction, including mystery and suspense tales, can become a laboratory for experiments with plot structure and narration. Connoisseurs of thrillers and detective stories know that they must read warily, for the author is often trying to deceive and mislead. My entries on Side Effects and Gone Girl afford some examples of the process.