The return of Homunculus

Sunday | November 15, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

On 21 November, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will be screening a version of Otto Rippert’s long-lost German serial Homunculus (1916). It was reconstructed by Stefan Drössler and his colleagues at the Munich Film Museum on the basis of material from the Moscow Film Archives and other collections. Here’s the background offered by the opening titles on this version.

Homunculus was shown as a six-part series in movie theaters in Germany and its occupied territories in 1916, in the midst of World War I. Each episode was about an hour long. In 1920 the opus was reissued as a three-part version. Scenes were shifted around and new intertitles added.

The following reconstruction adapts the structure of the reissue edition, but it also contains some scenes that had been shortened for the later version and often only survived as photographs.

Fewer than 20% of the original German intertitles have been preserved or are known in their exact wording. Newly worded texts for this reconstruction were based, when possible, on information from contemporary program notes and reviews; also, some were translated back from foreign-language versions of the film and others were created from keywords scratched into the film as montage cues.

For the first time, the current work print makes it possible to recognize the original concept of the entire series.

Today, as a preparation for this very important event, each of us offers you something. First Kristin sketches the trend of fantasy filmmaking in German cinema of the 1910s. After providing this context for the film, David offers some thoughts on this new version of Homunculus and its value for us today.

Kristin here:

The seeds of Expressionism

Many viewers who come to Homunculus for the first time may be expecting traits of the most famous German silent film trend, Expressionism. And indeed historians have mentioned Rippert’s serial, along with Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague, 1913), Hoffmanns Erzählungen (Tales of Hoffman, Richard Oswald, 1916), and others, as forerunners of the Expressionist movement.

But we don’t have a very concrete account of how these earlier films led up to the more famous trend that began with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’s release in early 1920. Moreover, at first glance there aren’t many visual qualities in these earlier films that remind you of Expressionism. They display few or none of those Expressionist distortions of mise-en-scene influenced by contemporary trends in painting and theatre. Similarly, the acting, while exaggerated in a fashion common during the 1910s, seldom reaches the extreme stylization of the performances in Expressionist films.

Yet there are clearly some other similarities between the two groups of films. Most obviously, the early films brought to prominence two related genres to which many of the Expressionist films would belong: the phantastischen film and the Märchenfilm, or fairy-tale film.The main examples of the latter all starred Paul Wegener: Rattenfänger von Hameln (The Pied Piper of Hameln, 1918), Hans Trutz im Schlaraffenland (Hans Trutz in the Land of Cockaigne, 1917), and Rübezahls Hochzeit (Rübezahl’s Wedding, 1916).

For Expressionist filmmakers, elements of the supernatural or the legendary could motivate highly stylized mise-en-scene. In contrast, these 1910s films often used relatively realistic mise-en-scene. Location shooting, straightforward period costumes, and skillfully executed trick photography introduced the fantastic elements into the milieu of a concrete, seemingly everyday world.

A changing view of cinema

Despite such differences, the two genres provide a specific link between some of the most prominent German films of the 1910s and those of the Expressionist movement. Moreover, fantasy films seem to have provided a basis for at least a tentative exploration of theoretical issues surrounding the relationship of cinema to the other arts. In Germany, cinema had previously been compared primarily to literary and theatrical arts, but Wegener’s Der Student von Prag and other films led to a wider consideration of cinema in relation to visual arts such as painting.

In a 1916 lecture, Wegener expressed dissatisfaction with most of what had previously been done with the cinema. He sought to establish the cinema as an independent visual art, separated from theatre and literature:

When a new technology is developed, it is initially cultivated in relation to existing ones, and a new idea does not immediately find its own unique form. The first steamboats looked like big sailing schooners, except that instead of masts they had high funnels. The first railway cars copied mail coaches, the first automobiles kept the large bodies of landaus, and the cinema was like pantomime, drama, or the illustrated novel.

A more broadly based view of the cinema as combining theatrical and graphic arts created a newtradition which carried over from the 1910s to the Expressionist movement of the 1920s. These early films may have become models for the development of an “art cinema” movement in the next decade.

The painterly approach to film promulgated by Wegener lingered in German cinema for about a decade. Starting around 1924, a new approach, based on the moving camera and a more realistic three-dimensional space, would largely replace the older one.

Frames and books

Der Student von Prag.

Aside from this specific link created by Wegener’s emphasis on the pictorial powers of the camera, several conventions of the fantasy films of the 1910s look forward to Expressionism. Perhaps most notable among these devices is the use of the frame story.

Expressionist films frequently employ this device: Francis’ tale to the fellow asylum inmate in Caligari, the record of the Bremen town historian in Nosferatu (as well as the imbedded narratives of the Book of the Vampyres and the ship’s log), the young poet hired to write publicity anecdotes for a sideshow in Wachsfigurenkabinett, and so on.

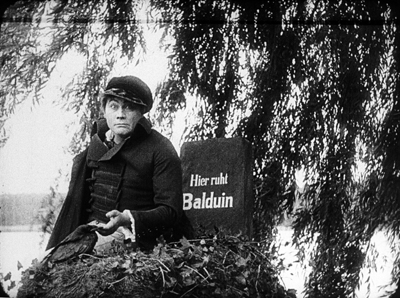

Yet this pattern was already well established during the 1910s. Der Student von Prag begins and ends with a poetic scroll (“Ich bin kein Gott/bin kein Dämon …”), with the final return leading to a shot of Balduin’s gravestone—upon which sit the Doppelgänger and a crow. (The 1926 remake, which has some distinct Expressionist touches, begins and ends with a gravestone that summarizes Balduin’s life.) Wegener’s other major surviving film from the mid-1910s, Rübezahls Hochzeit, begins with a scene of Wegener, as himself rather than in character as the titular hero, reading to a group of children from a book entitled Rübezahls Hochzeit.

In some cases the frame story introduces multiple embedded narratives. Richard Oswald’s two main fantasy films of the pre-1920 era, Hoffmanns Erzählungen (1916) and Unheimliche Geschichten (Uncanny Stories, 1919), both use this technique. The first begins with a prologue showing Hoffmann surrounded by strange characters like Count Dapertutto and Coppelius. Three dream sequences show him incorporating these figures into bizarre stories; the transition from the prologue to the the main portion of the story begins with Hoffmann in bed as the three sinister figures stand over him.

Unheimlische Geschichten begins, as an intertitle announces, with “A fantastic Prologue at an antiquarian book dealer’s.” On the wall are three large pictures depicting a whore, death, and the devil. After the proprietor chases away his customers and departs, the three images come to life and amuse each other by reading tales out of a book. The series of embedded tales, adapted from Poe, Hoffmann, and other authors of the uncanny, form the bulk of the film.

Not all fantasy films of the 1910s contain frame stories or embedded narratives. Characters do, however, often read or write books that contribute major premises or motifs. In Homunculus, Richard Ortmann keeps a large diary, which records his shifting and somewhat contradictory thoughts, feelings and goals—and thus conveys them to us. Joe May’s Hilde Warren und der Tod (Hilde Warren and Death, 1917) also has no frame story. Its opening, however, involves the heroine reading in a book that death is an escape from sadness. This notion becomes a motif, as the figure of Death appears to her at intervals, foreshadowing her eventual surrender. Books would become an important motivating device in Expressionist films, introducing embedded narratives or crucial motifs.

Hilde Warren und der Tod also carries through the pictorial tradition of Der Student von Prag. Here the special effects are not used to allow one actor to play two roles through split exposure. Rather, superimpositions introduce the figure of Death into the everyday scenes of Hilde’s life.

Some early hints of Expressionism

Although the fantasy films of the 1910s don’t contain strongly Expressionist elements, a few stylistic touches foreshadow the distortions of the later movement. Some of these relate to performances by actors who were to become central to the Expressionist movement. In Hoffmanns Erzählungen, for example, Werner Krauss’s stylized acting in the role of Count Dapertutto suggests why he was later cast as Dr. Caligari. Conrad Veidt’s acting and especially his makeup as Death in Unheimliche Geschichten mark him as the ideal candidate to show up in Caligari’s cabinet.

The stylized hand gestures in these two shots are particularly striking, and the same device is carried through in a séance sequence in Unheimliche Geschichten. The lighting of the séance looks forward to more famous scenes in Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), and The Ministry of Fear (1944)—yet here Oswald introduces a twist by including one more hand than there should be for the number of bodies present.

There are other major films made in 1919 which contain stylistic and generic elements soon to become far more prominent. Lang’s Die Spinnen (The Spiders, 1919-1920) draws upon conventions of the thriller serial which would soon by transmogrified in his Expressionist film, Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler. Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (The Puppet) and Die Austernprinzessin (The Oyster Princess), both 1919, could be counted as comic Expressionist films that introduced the style into the cinema months before the appearance of Caligari. The exact cut-off date between pre-Expressionism and Expressionism proper is not vitally important. Some 1910s developments in genre and style prepared the way for Expressionism. Caligari, however great its stylistic challenges were, did not appear in a vacuum.

DB here:

Wanted: Love. #Homunculus

The 1920 reissue of the Homunculus serial compresses its original story considerably, but the outlines are clear. Some omissions in the Munich reconstruction may reflect gaps in the 1920 version. Still, the basic outline of the tale is clear.

Very likely the first test-tube baby, the Homunculus arrives on the scene as the result of a pseudoscientific effort to create life. Out of a bubble, properly zapped, comes an infant.

The baby is brought up in an ordinary human family, thanks to the classic switched-in-the-cradle device. Known as Richard Ortmann, the creature grows up into something of a superman, with extraordinary strength and explosive energy. But his core is hollow. Richard discovers that he lacks fellow-feeling and finds himself alienated from his carousing peers.

When Richard discovers his technological origin, he sets himself a drastic choice: either discover human love or destroy this worthless world.

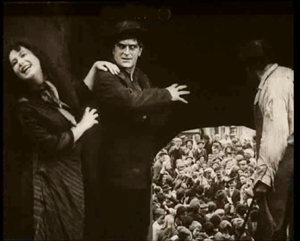

Each episode replays the same dynamic. Somewhere Richard discovers a possibility of uncorrupted love. But that prospect shatters, either because of prejudice (would you want your daughter to marry a homunculus?) or his sadistic urge to plunge the world into chaos. Only his friendship with Edgar Rodin, one of the scientists who attended his birth, forms an enduring bond across the episodes.

Richard Ortmann plays many roles in his saga. He’s a scientific tinkerer who invents an explosive, a wanderer who ventures into Africa, and a capitalist who enjoys masquerading as a rabble-rouser bent on fomenting rebellion. No sooner has he provoked a war than he tries his own social experiment, that of isolating a young couple in hope of breeding a new society. All these exploits he records in a mighty book

This tome becomes a handy narrative device when the plot demands that other characters learn of his inhuman origins.

Like those films that clone a Stallone or a Van Damme, the series realizes that one monster can be defeated only by another one. The long tale comes to a climax when Rodin creates a second Homunculus and raises him up to conquer Ortmann–already somewhat weakened from age and fear of death. The titanic confrontation is played out on mountain craigs.

Who will win? Or will both perish?

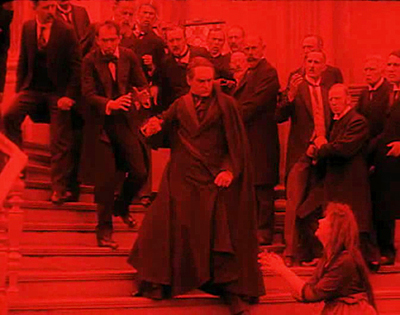

Annihilation, courtesy Homunculus

The rocking-horse rhythm of the episodes, with hope for Ortmann’s redemption rising and inevitably falling, takes some getting used to. To the filmmakers’ credit, they vary the prospects for love: an array of women, a dog, and in the fourth episode a woman who wholeheartedly embraces Ortmann’s wicked side.

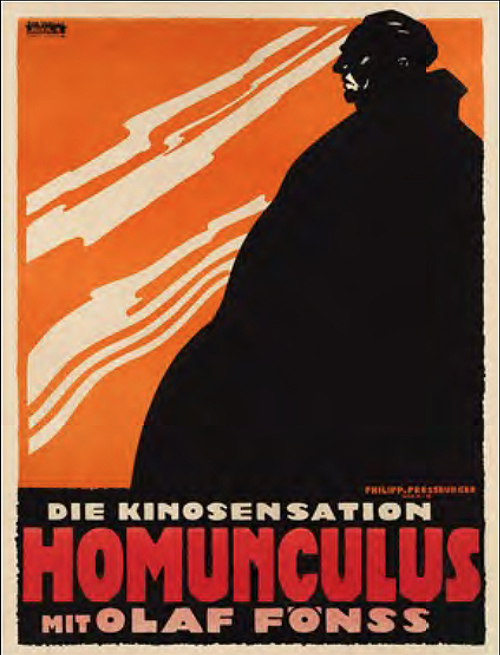

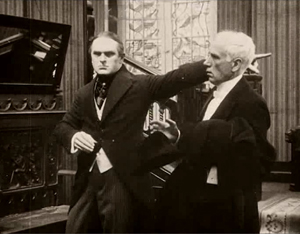

Today’s viewers will also need to accustom themselves to the seething extremes of Olaf Fønss’s performance. Fønss was a major Danish actor who became famous in Atlantis (1913) and who migrated to Germany to star in this series. Fønss conceives his performance as a matter of ferocious glares, raised fists, and heroically villainous postures. It looks overdone to us today.

His box cape, reminiscent of bat wings, helps the brooding effect.

But this isn’t merely a matter of old-fashioned hamming. Fønss’s performance is calibrated to be ragingly different from the other portrayals. Most of the actors exaggerate less, and the pacifist preacher actually underplays. Fønss goes over the top because Homunculus does.

What makes the series compelling? For one thing, it offers a fairly original reworking of the Frankenstein premise. For another, its central conceit of a mad, misunderstood supervillain in search of love can evoke some empathy. There’s also the effort to convey a world in flames, to suggest a cosmic catastrophe with minimal means. While the Great War devastates Europe offscreen, one can hardly avoid thinking of trenches and bombardment in blasted shots like these–which also look forward to the jagged decor of Expressionism.

The student of film technique will, I think, be struck by the filmmakers’ pictorial ambitions. It’s now clear that by focusing just on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) we have limited our sense of the wide-ranging visual discoveries of German cinema. Homunculus belongs with the splendid string of films that includes Der Tunnel (1915), Algol (1920), I.N.R.I. (1920), and the outstanding pair of 1919 films by Robert Reinert, Opium and Nerven. Reinert, unsurprisingly, wrote the screenplay for Homunculus.

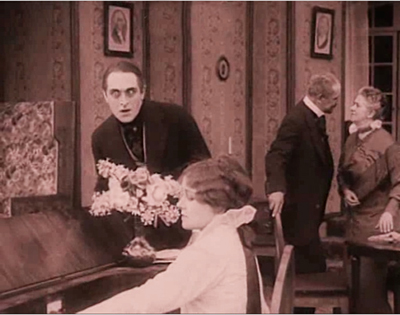

The fourth episode, which I commented on back in the summer (based on a much inferior copy), remains a treat for your eyes, with unexpected camera angles and daring use of depth. In the one on the left, we see touches of Expressionist performance in the orchestration of hands.

Elsewhere Kristin has remarked that during the 1910s filmmakers began to go beyond basic storytelling and explore the expressive dimensions of cinema—not only in acting but also in composition, lighting, and set design. The Jugendstil curves of the incubator gleam inside a cavernous chamber you might not expect to find in a lab.

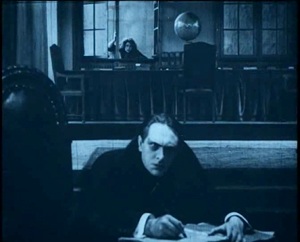

Other episodes provide both grand images—landscapes, sumptuous sets, crowd scenes—and an arresting, small-scale play of light and shade. A purely expository shot of Ortmann approaching Steffens’ study becomes a little suite of shadow patterns, stressed when Ortmann pauses and swivels to the camera and creates a pictorial climax.

Seeing the three-dimensional lighting effects of German cinema of the mid-1910s onward, I wonder whether Caligari‘s jutting, broken-up planes and painted shadows are not only a borrowing from Expressionist painting but also a reaction against the rich volumes created by directors like Rippert.

In all, Stefan Drössler and all the archives and individuals working with him have done world film culture a great service. As with Gance’s Napoleon and Lang’s Metropolis, more footage may appear and need to be integrated into this version. Perhaps some day we’ll have something approaching the full scope of the original series. For now, we should be thankful that another silent classic steps out of the shadows and forces us to rethink what we thought we knew about the history of cinema.

Many thanks to Stefan Drössler for his assistance in preparing this entry.

At Nitrateville Arndt has posted helpful synopses of all six parts of the restoration. Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel (Amsterdam University Press, 1996), pp. 160-167. Excerpts can be found here.

Kristin’s discussion of fantasy films is excerpted from her essay “Im Anfang War…: Some Links between German Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” in Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Bibliotexa dell’Immagine, 1990), 138-161. The Wegener quotation is from Paul Wegener, “Die künsterlischen Möglichkeiten des Films,” in Kai Möller, ed., Paul Wegener: Sein Leben und seine Rollen (Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag, 1954), p. 102. Translation by KT.

Elsewhere on this site we discuss other neglected German films of the period: Der Stoltz der Firma (The Pride of the Firm, 1914); Der Tunnel (1915); Asta Nielsen features of the teens; Doktor Satansohn (1916); Hilde Warren und der Tod (1917); Die Pest in Florenz (The Plague in Florence, 1919, directed by Rippert after Homunculus); late-1910s Lubitsch; Algol and I. N.R.I. (both 1920); and Der Golem (1920). I have an essay on Robert Reinert’s remarkable films in Poetics of Cinema. Some day I hope to write more about Paul Leni’s war drama Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, 1917) and Joe May’s energetic and entertaining serial Die Herrin der Welt (Mistress of the World, 1919).