The first Sherlock and other video releases for the holidays

Tuesday | December 1, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

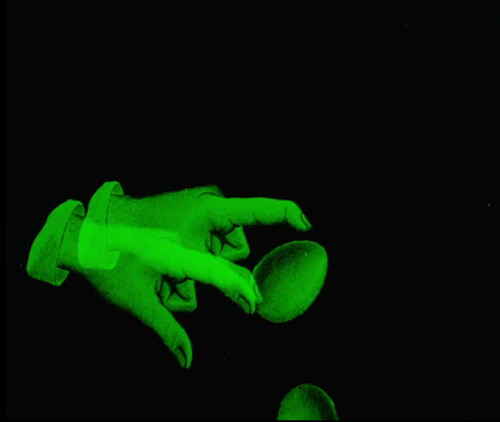

Our Lady of the Sphere (Lawrence Jordan, 1969)

Kristin here–

Our friends at Flicker Alley have offered three major releases since early October: Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 (October 6), Sherlock Holmes (November 10), and Chaplin’s Essanay Films 1915 (November 17). This may seem ridiculously fast-paced, but it is partly explained by a delay in the release of Sherlock Holmes. All three editions package Blu-ray and DVD versions together.

In the move from 16mm to digital, avant-garde cinema was initially left behind. Eventually big boxes and series of DVD releases made a huge number of experimental short films available to audiences who may  have had little access to such fare before. In quick succession, Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1894-1941 (2005), Kino’s three-volume series Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema 1920s and ’30s (2005), Experimental Cinema 1928-1954 (2007), and Experimental Cinema 1922-1954 (2009), and the forth volume of the “American Treasures” series, Avant-Garde Film 1947-1986 (2009) were released.

have had little access to such fare before. In quick succession, Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1894-1941 (2005), Kino’s three-volume series Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema 1920s and ’30s (2005), Experimental Cinema 1928-1954 (2007), and Experimental Cinema 1922-1954 (2009), and the forth volume of the “American Treasures” series, Avant-Garde Film 1947-1986 (2009) were released.

Now we have another ambitious set, Masterworks of American Avant-Garde Experimental Film 1920-1907. Fans of experimental cinema who have purchased all of the earlier sets might wonder if there is room for yet another extensive collection of American films. Won’t there be a lot of overlap? The answer is a definite no. The body of work by important avant-garde filmmakers is extensive enough to support many boxed-sets.

I can find not a single film in the seven DVDs in Unseen Cinema (which takes a rather broad view of what counts as avant-garde) that is duplicated here. The same is true of the Avant-Garde Film 1947-1986 set. The Kino boxed sets (two discs each) are heavily slanted toward international films, and there is a slight overlap. Flicker Alley’s website has a list of all 37 titles included in Masterworks.

It’s impossible to deal with all the films included in the set here. (The film illustrated at the top is one of them.) I’ll just say that I was happy to see Hilary Harris’ 9 Variations on a Dance Theme (1966/67, right). We used to show it in the introductory film course we taught back in the mid-1970s, when Film Art had not yet been dreamt of. It’s a lovely film in itself, but it also might possibly be the clearest way to get across the ideas of form and style that one could find. Starting with a long shot of the dancer in a segment that simply records her movements, documentary style, the film repeats the same music and choreography eight times, with the cinematography and editing rendering a progressively abstract set of images.

Flicker Alley has put together an essential collection of films that will be new and exciting to many fans. The extras include, generously, three other experimental films. A a helpful booklet contains an introduction by Bruce Posner and brief program notes and filmmaker bios.

The Return of Sherlock Holmes

Until recently the 1916 version of Sherlock Holmes, based on the play by William Gillette, was lost. That seemed exceptionally unfortunate, not only for legions of Holmes fans but for anyone interested in late Victorian stage practices. Gillette’s performance as Holmes was considered the defining one, influencing subsequent portrayals. The play, which was produced in the US in 1899, had the cooperation of Arthur Conan Doyle, whom Gillette consulted during the period when he was writing it. The film version was a precious record from the time when the Holmes series was still being written.

In fact, Conan Doyle had killed Holmes off in 1893 in “The Final Problem,” and at the time when he authorized the play, he still had not resurrected his popular character. Gillette’s play influenced the later stories with such additions the character of the young servant Billy, a character invented by Gillette and later used by Conan Doyle.

In one of those happy endings that occasionally happen with lost films, a copy was discovered in the Cinémathèque française. Not just any old copy but the original nitrate negative of the French release version, which was shown as a serial in four parts in 1919. Apparently no footage was lost, and the main difference between the restored version that we have now and the original American feature film is that the new intertitles have been translated from those of the French release.

The original play has four acts, and the film has compromised between maintaining the interior setting of each act for a long stretch of the film and opening it out with brief exterior scenes and cutaways to other locales. One very lengthy section of the film takes place in the isolated house used by the villains to imprison the heroine, Alice. The sets are somewhat reminiscent of the stage, and yet they have been extended forward, and at times we see at least three walls and perhaps part of a fourth. In many cases, the stage-style set is made more cinematic through the simple device of adding some furniture in the foreground (left). In others, the characters are strung out in a line across the playing space, as in the final “act,” which takes place in Dr. Watson’s office (right).

Physically, Gillette makes a convincing Holmes in terms of the way Conan Doyle describes him, and his performance is restrained and usually lacking in expressivity–which works for a character noted for not exhibiting emotion. Unfortunately Gillette added a love interest for Holmes. Doyle, who apparently didn’t care what others did with Holmes now that he was rid of him, gave his permission. This would be bad enough in itself, but Alice is quite young looking, and Holmes is much older than she. Gillette had originated the role seventeen years earlier, when he was 46. By the time the film was made, he was 63, and though he doesn’t look that old in the film, the age difference between Holmes and Alice is obvious.

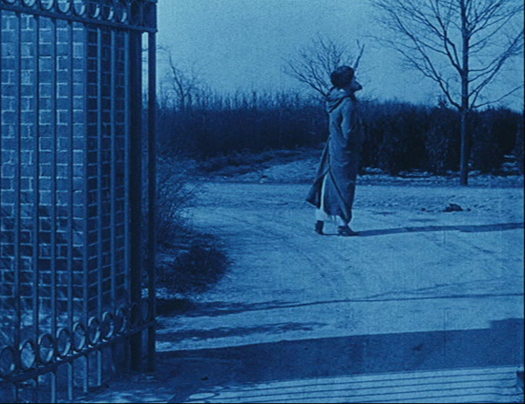

Given the survival of the negative, the Blu-ray/DVD transfer is impressive. Serpia toning is used in most scenes, while dark blue tinting represents night exteriors, many of which are nicely filmed (see bottom). The music is by Neil Brand, one of the best accompanists in the business.

There are generous bonuses, including some earlier comic shorts based around the character, Conan Doyle’s Fox Movietone interview, and a typescript of Gillette’s play. The set comes with a booklet with short essays on Gillette and his play, the film adaptation, the restoration, and the music.

The Little Tramp takes shape

Jeffrey Vance begins his essay on Chaplin in the booklet accompanying Chaplin’s Essanay Comedies 1915 with this observation:

If the early slapstick comedy of the Keystone Film Company represents Charles Chaplin’s cinematic infancy, the films he made for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company are his adolescence. The Essanays find Chaplin in transition, taking greater time and care with each film, experimenting with new ideas, and adding textue to the Little Tramp character that would become his legacy. Chaplin’s Essanay Comedies would become his legacy. Chaplin’s Essanay comedies reveal an artist experimenting with his palette and finding his craft.

The unstated conclusion to the series of companies where Chaplin worked during the 1910s is that the Mutual period saw Chaplin’s maturity as an artist. Flicker Alley has now completed its epic survey of all three periods, with copies restored by the Cineteca Bologna and Lobster Films in cooperation with Blackhawk Films and the Chaplin Mutual and Essanay Project. Many archives provided material. For those who first saw Chaplin in worn 8mm and 16mm copies, these prints are a revelation.

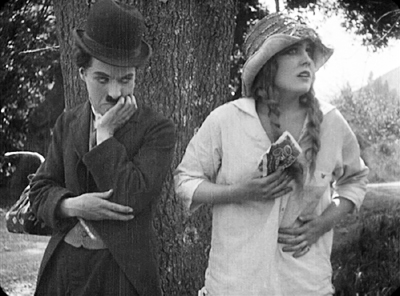

Chaplin’s tinkering with his Tramp character is evident in the most famous short in the set, The Tramp. It begins and ends with the character on the road, going nowhere in particular. In between are sandwiched broad slapstick scenes, quieter comic moments, and a big of the pathos that would become increasingly central to the Tramp.

Early in the film he is capable of saving an innocent farm girl with a wad of money from a trio of thieving hobos, then stealing the money himself (above), and then relenting and giving it back. His comic pacing is sometimes off–way off in an overlong scene of the Tramp, who gets a job at the heroine’s farm, repeatedly poking a fellow farmhand with a pitchfork (a pretty cliched gag to begin with). The Tramp’s clueless attempts at milking a cow work distinctly better, as he tries everything, including turning the cow’s tail into a pump handle. That’s the sort of visual punning that would become one of Chaplin’s comic strengths. There are some funnier scenes, as when the Tramp is forced to bunk in with the farmhand and suffers agonies from his roommate’s smelly socks.

Some quietly funny moments are better, though, as when the Tramp, having been wounded in the leg while trying to foil a burglary attempt, sits complacently enjoying his leisure and assuming that the heroine is in love with him. The absent boyfriend, well-dressed and handsome, soon shows up and, recognizing the inevitable, the Tramp removes himself from the triangle and takes to the road once more. Perhaps more than any other image, this one summarizes how Chaplin’s Tramp was thought of for many years and by millions of people.

Bonuses include some films using discarded footage or cutting together scenes from already-released shorts, as Essanay tried to capitalize as much as possible on Chaplin’s extraordinary international popularity. There is also a booklet with Vance’s essay and a set of program notes. Each of these has a brief description of the restoration process, which is a nice thing to see in a supplement.

Sherlock Holmes (1916)