Archive for 2016

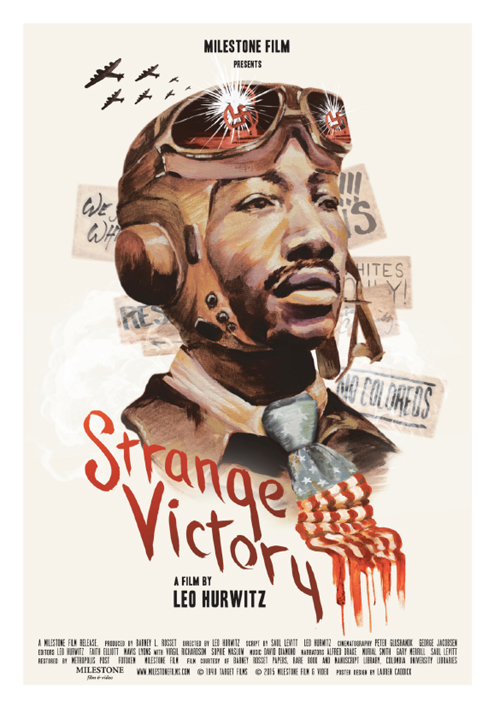

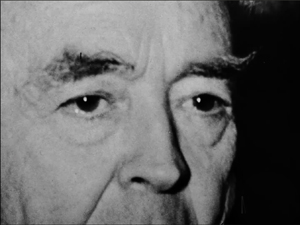

Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948)

DB here:

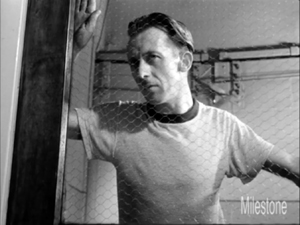

Leo Hurwitz is perhaps best known for Native Land (1942), the documentary codirected with Paul Strand and narrated by Paul Robeson. Strange Victory (1948) has been less easy to see. It was scarcely distributed and, though some reviews praised it, it was accused of Communistic sympathies. Now, restored and recirculated by the enterprising Milestone Films, Strange Victory has lost none of its compassion and righteous anger. Thanks to the energy of the Milestone team, led by A my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

In a period of postwar optimism, Hurwitz and his colleagues dared to point out that the prejudices exploited by the Nazis remained powerfully present in the United States. The winners, it seemed, hadn’t repudiated the bigotry of the losers. American racism persisted and even intensified. The Nazis lost, but a form of Nazism won.

Dec. 14, 2015, in Las Vegas. Individuals at a Trump rally yelled “Sieg Heil” and “Light the motherfucker on fire” toward a black protester who was being physically removed by security staffers.

News of the world

Like The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), on which Hurwitz was cameraman, and the Why We Fight series, Strange Victory is largely a compilation documentary. Guided by voice-over narration, it ranges across newsreels of Hitler’s rise, chilling combat shots, and footage from the liberated death camps.

But Hurwitz and his team shot a lot of new material as well, with an eye to bringing out the postwar significance of their theme. Newborn babies eye the camera, and kids play on sidewalks and in backlots (some shots recall Helen Levitt’s evocative street photos). Meanwhile, anxious adults approach a newsstand. “If we won, why are we unhappy?” the narrator asks at the beginning. The question is answered at the end: “There was not enough victory to go around.”

Thanks to a hidden camera, that newsstand becomes a sort of gathering spot, a place where people might encounter uncomfortable truths. Intercut with people buying newspapers are images of battles, as if the hunger for news aroused by the war didn’t dissipate. But what is that news? Hurwitz introduces it quickly: the rise of nativist bigotry. In an eye-blink, racist decals are slapped on fences, synagogues are smashed, and vicious pamphlets swarm through the frame. Race-baiting politicians, radio hate-mongers, and fascist sympathizers–the 1940s equivalents of our celebrity demagogues–are pictured and named. This is just one of many passages that guaranteed that Strange Victory could never be circulated on mainstream theatre circuits.

Hurwitz mixes found footage, stills, posed images, and fully staged scenes, such as the episode in which a Tuskegee Airman tries to find a job with an airline. In this mixed strategy he follows not only the precedent of the March of Time series but also, and more self-consciously, the Soviet documentarist Dziga Vertov.

In a 1934 article, Hurwitz called The Man with a Movie Camera “the textbook of technical possibilities,” and he isn’t shy about mimicking the master. Early in the film, portraying the Allies’ victory, a shot shows a swastika-emblazoned building blown to bits in slow motion. Later, to convey the return of Hitlerism, the same shot is run backward, reinstating the swastika on the building’s roof. A graphically matched dissolve equates a Klan wizard with Southern senator John Elliott Rankin.

Later, via constructive editing à la Kuleshov, parental pride is made color-blind, as both a white mother and a black one return a father’s glance.

The film hasn’t aged a bit. The print is gorgeously subtle black and white, and the score by the underrated David Diamond is warm in a chamber-music way. The film’s vigorous voice-over and its ricocheting images (some returning as refrains, bearing new implications) look forward to the hallucinatory, expanding associations created by our most biting contemporary documentarist, Adam Curtis.

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

One of the individuals involved in the confrontation with Nwanguma was Joseph Pryor, a native of Corydon, Indiana, who graduated from high school last year. After the rally, Corydon posted a photo on his Facebook page that showed him shouting at Nwanguma. The post went viral and eventually attracted the attention of the Marine Corps, which Pryor had just joined.

The Marine Corps recruiting station in Louisville told military publication Stars and Stripes that Pryor had recently enlisted and was about to head off for boot camp. Captain Oliver David, a spokesman for the Marine Corps command, said Pryor had not yet undergone Marine Corps ethics training. . . . He added: “Hatred toward any group of individuals is not tolerated in the Marine Corps and he is being discharged from our delayed entry program effective [Wednesday].”

The tyranny of facts

As ever, the ordering of parts matters greatly. How best to convey the idea that after a struggle to cleanse Europe of violent prejudice, the same attitude is flourishing in America? You might think of couching your argument as a narrative. In chronological order, that would be: The rise of Hitler; the war defeating Hitler; the celebration of victory; the return of American bigotry in the postwar period. Clear and straightforward.

Hurwitz is more canny. Many films embracing rhetorical form, like the problem/solution structure of Pare Lorentz’s The River (1938), will embed brief narratives into their overarching argument. This is Hurwitz’s approach, but his stories aren’t chronologically sequenced. Instead, we start with the America of today before flashing back to the high price of defeating the Axis. “Everybody paid,” says the male narrator. “Everybody.” With a pause to register Roosevelt’s death, jubilation surges up as the Nazis fall. “For a day or two, the plain people owned the world.” But then we’re back to the newsstand and a montage of race-baiters and graffiti scrawlers.

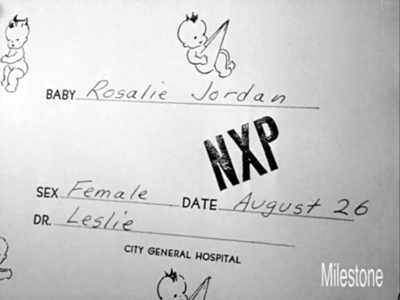

Then, as we see a pregnant woman on a bench, we hear a woman’s voice. Her poetic musings reassure the newborn babies that they have a place here; she welcomes them to earthly love. Following the montage of haters with images of innocence casts a melancholy pall over these fresh-begun lives. They know nothing of the American brownshirts, but we know that they must learn our world.

This foreboding is confirmed by a chorus of name-calling over shots of newborns, the woman’s song of innocence is undercut by a song of bitter experience. A new male narrator (Gary Merrill) raps out the facts of “our daily barbarisms.” Get ready, he warns the babies: You will be tagged and vilified by how you look and where you live. “Separation of people is a living fact,” and they are future “casualties of war.” Throughout the rest of the film, the shots of children carry a terrible aura; they have no idea of what they’re facing.

Now, after a long delay, we flash back to Hitler’s rise. The Führer’s strategy, funded by the rich, is seen as a deliberate mobilization of just these tribal “facts” for the sole end of acquiring power. And where that process ends is the death camp. In a chilling visual refrain, the happy American toddlers are compared to troops of children marched along barbed wire.

The narrative spirals back to the beginning. Again we see Hitler defeated, again ecstatic celebrations–but not, as before, among civilians in cities. Instead, we see Russian and American soldiers fraternizing, and included in this mix is the black pilot, smiling serenely in his cockpit. His presence was foreshadowed by swooping aerial shots of the beginning. Now we’re back to the present, and he’s looking for work. No luck; maybe he can be a porter? A new montage generalizes his plight: American society refuses to assimilate African Americans. A savage cut takes us from a room full of white secretaries to a cotton field–the only work available for people who participated as fully in the war effort as anyone.

Now the early montage of Jim Crow images is recalled in a poetic string of associations on the word word, from Hitler’s control of The Word to signs barring blacks from entry, ending with inscriptions etched on forearms.

The final images of passersby, filmed unawares, replace the newsstand of the opening with shop windows as they peer inside. The sequence uncannily predicts the explosive consumer society that would follow in the war’s wake. Again, though, a shadow falls over the postwar world. Hurwitz daringly intercuts the intent window-shoppers with the plunder of the camps–hair, jewelry–and the numbers on inmate uniforms, as if these were commodities on display.

The war against inhumanity is far from over. Americans will need to be more than curious consumers if they are to face the struggle that lies ahead.

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

Strange Victory is, it seems to me, the essential documentary of our moment. A nearly seventy-year-old film can remind us that, as the narration puts it, “hopelessness is next door to hysteria.” The frustrations, despair, and hatreds that surfaced during Obama’s tenure have crystallized in an American fascist movement of unprecedented breadth. The film reminds us that scapegoating is eternal, sometimes summoned quietly (they’re not like us, she’s a traitor, he knows exactly what he’s doing), sometimes conjured up in full fury. At a moment when America is one IS attack away from a Trump or Cruz presidency, it’s good to be reminded how the well-funded Hitler exploited Us vs. Them. Temporizing pundits give every sufficiently funded lunatic the benefit of straight-faced interviews, or even tongue-baths. Right-wing politicians and agitators, keen on power and uncommitted to principle, are ready to fall in line behind a leader if he might win. Forget Godwin’s Law. Facing today’s assault on peace and justice, Strange Victory can rekindle our energies, without a moment to lose.

The crematorium is no longer in use. The devices of the Nazis are out of date. Nine million dead haunt this landscape. Who is on the lookout from this strange tower to warn us of the coming of new executioners? Are their faces really different from our own? Somewhere among us, there are lucky Kapos, reinstated officers, and unknown informers. There are those who refused to believe this, or believed it only from time to time. And there are those of us who sincerely look upon the ruins today, as if the old concentration camp monster were dead and buried beneath them. Those who pretend to take hope again as the image fades, as though there were a cure for the plague of these camps. Those of us who pretend to believe that all this happened only once, at a certain time and in a certain place, and those who refuse to see, who do not hear the cry to the end of time.

Milestone, who gave us the restored Portrait of Jason, has provided a very full presskit for Strange Victory here. My final quotation comes from Jean Cayrol’s text for Night and Fog (1955).

Strange Victory (1948).

Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop

Ant-Man 2: This time it’s personal. Not that it wasn’t before. But now it’s personal and expensive.

DB here:

Sean Parker, the Napster founder who taught everybody that digital piracy means never having to say you’re sorry, has come up with a new killer app. Called The Screening Room, the pitch is catching the eye of an industry that thrives on finding new niches for its product.

Stuff you probably already know

Recall, as background, that Hollywood’s economic model depends on two conditions.

(1) Strong Intellectual Property measures, both technological and legal. (Intellectual is to be taken in a broad sense here. It includes Paul Blart movies.) Encryption is designed to protect DVDs, streaming, and the Digital Cinema Package that plays in your local multiplex. Law enforcement, under the auspices of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, backs up anti-piracy with fines and jail time.

(2) Price discrimination. The premise of the classic vertically-integrated studio system was that people will pay more to see a movie sooner than other people. Why this is true still mystifies me, but facts are facts. Hence the old system of “runs.” First-run movies demanded top dollar, then second runs were at lower prices, and subsequent runs were still cheaper. When the studios surrendered their theatre ownership, the runs system remained roughly in place, chiefly because most films were platform released, playing the big cities before gradually expanding to the provinces. And network TV was basically the only ancillary market. But wide releases–hundreds or even thousands of copies playing everywhere–became the industry norm as cable, home video, and other technologies came along. The run system was reborn, and price discrimination became much more fine-grained.

Known, confusingly, as “windows,” phases of the film’s life are assigned to various platforms. After the theatrical window, typically 90 days after release, there are windows for airline/hotel access, disc (DVD, Blu-ray), Pay-per-View, streaming, cable, and on down the line. The order of these windows for any one title can vary somewhat, depending on negotiations. Most of them are designed to define price points scaled along a curve: how much it’s worth to somebody to see the movie at intervals after the initial theatrical release. By the time a movie comes to free cable, you’ve pretty much squeezed everything out of it, though the industry relies very extensively on worldwide cable purchases.

The studios depend on the theatrical release, but not because it’s the biggest source of revenue. (For the top films it can yield a lot, of course, but most films don’t recoup their costs in that window.) The theatrical release builds awareness, making it stand out downstream in the ancillaries. Without theatrical release, a film needs a lot of publicity to draw notice. Witness all those films on your Netflix or Hulu menu, all those John Cusack movies you didn’t know existed.

Independent films are increasingly relying on day-and-date release between a mild theatrical run and some form of Video on Demand. Other indie titles, along with foreign ones, are going wholly VOD, and the big players–Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon–are vigorously buying titles and backing new projects against the looming day when the studios will license fewer blockbusters to them.

The studios need the theatre chains as a shop window for their top-tier product. The theatre chains obviously need the studios to keep crowds flowing in. But some parties have flirted with day-and-date theatrical/VOD. Most famously Ted Sarandos of Netflix argued for it in 2013, then had to backtrack a few days later. On the studio end, Universal in 2011 proposed softening the theatrical window by offering Tower Heist on “premium VOD.” The plan was to drastically cut into the theatrical window by making the film available after three weeks of release, for the hefty price of $59.95. Theatre owners threatened to boycott the film, and filmmakers howled in protest. Many feared that it was the thin edge of a wedge that would eventually, through price wars, shorten windows and lower prices–not to mention wreck theatre attendance. The idea was quickly dropped.

No bad idea ever goes away, as we learn from claims that tax cuts create jobs and that we’re just one intervention away from creating peace in the world. Thanks to Parker, we now have Premium VOD in a new guise. That means a new window, with corresponding price discrimination.

Premium VOD, steroidal

Last week, The Screening Room project, sponsored by Parker and entrepreneur Prem Akkaraju, was made public. Brent Lang of Variety outlined the plan circulating among the major players.

Individuals briefed on the plan said Screening Room would charge about $150 for access to the set-top box that transmits the movies and charge $50 per view. Consumers have a 48-hour window to view the film.

To get exhibitors on board, the company proposes cutting them in on a significant percentage of the revenue, as much as $20 of the fee. As an added incentive to theater owners, Screening Room is also offering customers who pay the $50 two free tickets to see the movie at a cinema of their choice. That way, exhibitors would get the added benefit of profiting from concession sales to those moviegoers.

Participating distributors would also get a cut of the $50-per-view proceeds, also believed to be 20%, before Screening Room took its own fee of 10%.

Parker assures all stakeholders that the magic box would assure maximum antipiracy controls.

Since then, developments have been swift. Peter Jackson, Ron Howard, and J.J. Abrams are supporting the plan, while James Cameron is opposing it. The Cinemark and Regal chains, at this point the biggest theatre chains in the country, are against it, but there are hints that AMC, soon to be the biggest chain in the world if it’s allowed to purchase Carmike, might be interested. As for studios, Universal, Sony, and Fox are rumored to be considering the prospect. Once the give-and-take of dealmaking gets under way, there’s no telling what a final arrangement might look like.

What’s transparently clear is the opposition of the art-house sector. Tim League of Alamo Drafthouse issued the first warning on Monday, calling The Screening Room a “half-baked” idea. Today the Art House Convergence, an association of 600 theatres, issued a severe criticism of Parker’s plan. The open letter has been summarized in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. Indiewire has published it in its entirety, and I do the same, as follows.

The Art House Convergence, a specialty cinema organization representing 600 theaters and allied cinema exhibition businesses, strongly opposes Screening Room, the start-up backed by Napster co-founder Sean Parker and Prem Akkaraju. The proposed model is incongruous with the movie exhibition sector by devaluing the in-theater experience and enabling increased piracy. Furthermore, we seriously question the economics of the proposed revenue-sharing model.

We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model, nor are we arguing for the decrease in home entertainment availability for customers – most independent theaters already play alongside VOD and Premium VOD, and as exhibitors, we are acutely aware of patrons who stay home to watch films instead of coming out to our theaters.

Rather, we are focused on the impact this particular model will have on the cinema market as a whole. We strongly believe if the studios, distributors, and major chains adopt this model, we will see a wildfire spread of pirated content, and consequently, a decline in overall film profitability through the cannibalization of theatrical revenue. The theatrical experience is unique and beneficial to maximizing profit for films. A theatrical release contributes to healthy ancillary revenue generation and thus cinema grosses must be protected from the potential erosion effect of piracy.

The exhibition community was required to subscribe to DCI-compliance in a very material way – either by financing through VPF integrators (and those contracts have not yet expired) or by turning to other models which necessitated substantial time and commitment. Those exhibitors who were unable to make the transition were punished by a loss of product. The digital conversion had a substantial cost per theater, upwards of $100,000 per screen, all in the name of piracy eradication and lowering print, storage and delivery costs to benefit the distributors. How will Screening Room prevent piracy? If studios are concerned enough with projectionists and patrons videotaping a film in theaters that they provide security with night-vision goggles for premieres and opening weekends, how do they reason that an at-home viewer won’t set up a $40 HD camera and capture a near-pristine version of the film for immediate upload to torrent sites?

This proposed model would negate DCI-compliance by making first-run titles available to anyone with the set-top device for an incredibly low fee – how will Screening Room prevent the sale of these devices to an apartment complex, a bar owner, or any other individual or company interested in creating their own pop-up exhibition space? We must consider how the existing structures for exhibition will be affected or enforced, including rights fees, VPFs and box office percentages.

A model like this will also have a local economic impact by encouraging traditional moviegoers to stay home, reducing in-theater revenue and making high-quality pirated content readily available. This loss of revenue through box office decline and piracy will result in a loss of jobs, both entry level and long-term, from part time concessions and ticket-takers to full time projectionists and programmers, and will negatively impact local establishments in the restaurant industry and other nearby businesses. How many of today’s filmmakers started their careers at their local moviehouse?

There are many unanswered questions as to how this business model will actually work. The proposed model, as we have read in countless articles, suggests exhibitors will receive $20 for each film purchased. At first glance, an exhibitor may think it represents a small, but potentially steady, additional revenue stream. But how will this actually be divided among the number of theaters playing the purchased title; will exhibitors who open the title receive more than an exhibitor who does not get the title until several weeks later (based on a distributor’s decision); who will audit the revenue to ensure exhibitors are being paid fairly; does this revenue come from Screening Room or from the distributor… these are just a few of the issues yet to be explained.

Similarly, Screening Room promises to give each subscriber two free cinema tickets with each film purchase. Yet to be disclosed is how an exhibitor will recoup the value of those tickets from Screening Room so they can then pay the percentage of box office revenue owed to the distributor of the film. Yet to be explained is who will manage the ticket program details such as location choice, method of purchase, and so on. Will all exhibitors be expected to honor Screening Room free tickets, or will some exhibitors receive preferential treatment over others?

We strongly urge the studios, filmmakers, and exhibitors to truly consider the impact this model could have on the exhibition industry. We as the Art House and independent community have serious concerns regarding the security of an at-home set-top box system as well as the transparency and effectiveness of the revenue-sharing model. Our exhibition sector has always welcomed innovation, disruption and forward-thinking ideas, most especially onscreen through independent film; however, we do not see Screening Room as innovative or forward-thinking in our favor, rather we see it as inviting piracy and significantly decreasing the overall profitability of film releases.

At this time and with the information available to us we strongly encourage all studios to deny all content to this service.

One point of clarification. Some reports have interpreted the paragraph beginning “We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model…” as meaning that art-house programmers, managers, and owners are okay with day-and-date VOD. But many Art Housers wish that day-and-date VOD had been strangled in its cradle. For those people, “not debating” doesn’t mean “accepting” or “not disputing.” It means that this is not the occasion for taking issue with that feature of the concept, as the Parker proposal introduces serious problems of its own.

The churn around this proposal is turbulent; stories kept popping up as I was writing the entry. A useful update is here. To keep up to speed, you may want to visit these two summative links, one for Variety and the other for The Hollywood Reporter.

There were, and are, still second-run movie houses. To my joy, Ant-Man, released last summer, has been playing for at least seven months at our second-run house here in Madison. And in 35! Is this a record in modern times? Also, too: My Ant-Man image up top comes from the first film, not the sequel, which doesn’t yet exist. I was just fooling and pretending.

What’s the Art House Convergence? Visit their site here. My visit to their annual confab is recorded here. An updated version is available in Pandora’s Digital Box.

A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

Kristin here:

Some readers have been kind enough to ask if I would be writing a wrap-up entry on The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies now that the entire set of Peter Jackson’s films have appeared, including the extended edition of the last part. I was somewhat hesitant to do so. Five Armies is my least favorite among the six parts, and I have many fond associations with researching and writing about the Lord of the Rings films for The Frodo Franchise book and blog. Still, it makes sense to follow up on my previous comments on the strengths and weaknesses of the two earlier parts of the HOB trilogy and suggest how they continued on into this concluding chapter.

I have previously blogged three times about The Hobbit at intervals since just before the release of the first part. In September of 2012, I posted “A Hobbit is chubby, but is he padded?” In it I discussed the July 30 announcement that the film would be released in three parts rather than the originally announced two. I expressed cautious optimism, suggesting that there was enough material in the original novel plus the appendices of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings to create a film reasonably faithful to the original.

In mid-January of 2013, I posted a follow-up entry, “A Hobbit chubby, but is he off-balance?” The first part of the film, An Unexpected Journey, had been out for about a month, and I felt the additions mostly worked well, or at least were acceptable. I still think the first part is the best.

Almost exactly a year later, I added a third entry, based on the release of The Desolation of Smaug: “Is Tauriel more powerful than Eowyn? and other questions we shouldn’t have to ask.” By this point I felt that the project had considerably strayed in directions that betrayed Tolkien’s source material. As the title implies, I felt that the modest “prequel” film had also begun to swell inordinately and threatened to overshadow the fine trilogy that the filmmakers had made earlier.

These problems are even more evident in the final installment.

Marvelous moments

To be sure, there are some impressive shots and scenes in the final film. In the opening sequence of Five Armies, Smaug’s flights over the town and his confrontation with Bard are the most impressive parts of the scene, and the dragon’s death is appropriately enough its high point, both literally and figuratively. The overhead shot of his lifeless body drifting downward, seen against the inferno that he has created, is one of the best of the film (see top). It recalls the marvelous shot of him at the end of Desolation, emerging from Erebor covered in the coating of molten gold that the Dwarves had hoped would kill him and rising into the sky as he effortlessly shakes it off.

Some of the later shots in Erebor are wonderful as well. (See the image at the bottom.)

The climactic confrontation between Thorin and Azog on the frozen lake has been widely praised. It’s a complete invention of the filmmakers; there is nothing like it in the novel. It contains many lovely shots which, I must say, provide a welcome change from the crowded battle scenes. The lake is introduced as Kili and Fili creep along its edge, hoping to reach the summit of Ravenhill, where Azog had been located as he commands the battle. (See top of this section.)

The confrontation itself contains many impressive compositions, both as the two competitors circle each other and later as Thorin, mortally wounded, watches the Eagles swooping as Azog’s corpse lies in the foreground.

Surely one of the film’s best scenes is the one where Thorin, driven nearly mad by his obsession with the treasure, wanders on the solid-gold floor left behind by the failed attempt to kill Smaug by flooding him with molten gold. We see him wander over the floor as a hallucinatory vision of Smaug slithers through the gold below him (left). Finally Thorin imagines himself sinking into the gold 9Right), an overhead shot that echoes the one of Smaug’s death at the top of this entry.

Another very different high point is Bilbo’s arrival back at Bag End only to find himself presumed dead and an auction of his effects going on. No doubt fans were looking forward to seeing this scene from the book, and it delivers considerable humor as well as poignancy once Bilbo gets inside his nearly empty house and replaces the portraits of his parents on their hooks.

Gaps and missed opportunities

Some things that one would expect to see in the film are simply not there. In the opening framing scene in Unexpected Journey, the elderly Bilbo remarks that the little trunk in which he has stored the treasured objects from his adventure still “smells of troll.” In Unexpected Journey we see the Dwarves bury treasure in trunks, so that it may be collected later. In Five Armies, we see Bilbo carrying his trunk on his journey as he nears home. Yet we never see him and Gandalf return to the scene of the encounter with the trolls and dig up the treasure. In the book, they do so and agree to divide the loot. Why bother to place such emphasis on the trunk and show Bilbo taking it home with him if the story does not include him retrieving it on the way back to Bag End? We last saw the trolls’ trunks two films ago, and surely at least a mention of their retrieval would remind those unfamiliar with the book where Bilbo got this rather large piece of luggage. Surely at least in the extended version a minute or so could have been spared from the overextended battle scene.

As to gaps, the big battle at Dol Guldur ends with Saruman telling Elrond to take the weakened Galadriel back to Lothlorien and “Leave Sauron to me!”

This is one the largest dangling causes in the film, and yet it never comes to anything. In between the Hobbit and LOTR films, Saruman seems to have come under Sauron’s sway, but there is no indication as to how that might have happened. Causes that dangle need to be taken up and explained.

More generally, fans have complained that Bilbo often seems to be missing from his own story.

The original novel is told almost entirely from Bilbo’s point of view. There are only a few scenes where he is not present, and his personality gives the book considerable unity of narrative tone. In Martin Freeman, the filmmakers found the perfect actor to portray him. It is a pity that Bilbo has to cede so much of his screen time to Azog and Bolg and Alfrid and even Tauriel, pleasant though she is in some ways.

The expanded edition

As with all five other parts of this serial, Five Armies was released in an extended version. This added 20 minutes, as compared with 13 minutes for An Unexpected Journey and 25 for The Desolation of Smaug. (For a list of which scenes were extended or added to all three parts, see here.) In the two previous parts, the additions were mainly more conversations and characterization. In Desolation, for example, the brief scene of Gandalf, Bilbo, and the Dwarves visiting Beorn were significantly expanded. In Five Armies, however, much of the extra footage expanded the already lengthy battle scene. There are some pluses and minuses in this new material.

Fans of the book were particularly annoyed by the elimination of the funeral of Thorin, Kili, and Fili, and a short but touching scene of the Dwarves and Bilbo grieving over their bodies was restored. This scene establishes that the Arkenstone, the cause of so much strife, has been returned to Thorin and will rest on his body, thus wrapping up the question of what ultimately happened to it.

A few additions provided explanations for plot points, as when Gandalf visits Radagast’s home after being rescued from Dol Guldur and receives Radagast’s staff to replace his own–thus confirming fans’ speculations about where he got the new one. (See above.)

Whence came the giant rams on which Thorin, Kili, Fili, and Dwalin ride up Ravenhill? Now we learn that they were the mounts of part of Dain’s Dwarf army.

By the way, I’m puzzled by the Hobbit film’s the obsession with using odd animals for transportation: Thranduil’s elk, Dain’s hog, other Dwarves’ rams, and Radagast’s bunny sled. The only one that comes from the book is the habit of orcs riding wolves and wargs, though we do know from LOTR that Dwarves don’t like riding horses–but Elves certainly do.

The one quiet conversation that was added has Bilbo talking with Bofur (in a track entitled “The Night Watch”). Bofur strongly hints that Bilbo would be justified if he simply slipped out and returned home before the battle starts, but Bilbo assures him he’s not leaving.

I suppose it’s a nice little reversal in the scene in Unexpected Journey when Bilbo does try to slip out of the cave in which the group are sleeping and go home. There Bofur spots him and kindly wishes him well. He is one of the few Dwarves that Bilbo seems especially to befriend, but it doesn’t really add much. In fact, about half of the Dwarves have been relegated to barely speaking. Some seem to have no audible lines, and some are barely glimpsed. It’s a considerable change from the earlier parts, where the writers took care to give each of them bits of business or dialogue.

One Dwarf’s role is considerably filled out from his relatively brief role in the theatrical edition. Dain Ironfoot, Thorin’s hog-riding cousin, now has considerable dialogue and swings a mighty war-hammer in battle. He is a much more comic character than in the book, which is unfortunate in that it makes him seem an inappropriate figure to replace the serious, majestic Thorin as King under the Mountain.

His salty language, though relatively mild as profanity (calling his foes bastards and buggers), is out of keeping with the language in the rest of the series. There is also some unintended humor as Dain and Thorin are able to pause in the midst of a crowded and chaotic battle to greet each other, exchange pleasantries, and discuss strategy, with the melee conveniently receding to provide them a little safety zone. Their discussion does help us a bit in understanding what is now an even more scattered, confusing battle scene.

Finally, we find out in this longer version how the comic villain Alfrid met his well-deserved end. Attempting to flee with some gold coins he has discovered, he hides on a catapult and inadvertently sends himself hurtling into the mouth of a large troll.

Alfrid, who does not exist in the novel, was a tolerable figure while the characters were still in Laketown and he could interact with the Master. Bringing him safely ashore and making him part of the actions of the citizens as they take refuge in the ruins of Dale, however, was in my opinion a big mistake. Without any justification, he becomes a sort of assistant to Bard. Fans widely expressed mystification as to why Bard and even Gandalf would give him important duties to perform when both should know that he is completely unreliable, foolish, dishonest, and selfish. In general he injects a humor that undercuts the serious nature of many of the scenes. He, like the Master, should have been left to go down with the ship back in Laketown.

Increased violence

Throughout the LOTR and Hobbit series, the filmmakers have pushed the limits of the rating system, always achieving a hard PG-13 label for both the theatrical and extended versions. With Five Armies, they have for the first time crossed the limit and been given an R rating, though only for the extended edition.

I see this as something of a betrayal of the fans, especially families, who have fallen in love with this franchise, sharing the films over many years. The reason for the R rating is probably entirely due to some extreme violence and cruelty. Certainly there is no sexual basis for such a rating, and the mild profanity mentioned above, introduced with the character of Thorin’s cousin Dain seems unlikely to have been a significant cause of the stricter rating.

One particularly disturbing figure is a troll who figures prominently in the battle. He has apparently had all four limbs systematically amputated and replaced with prostheses in the form of giant metal weapons. Moreover, he is controlled by a rider who guides him with reins made of large chains attached to his blinded eye sockets with hooks. While most of the trolls who serve the enemy’s troops seem to do so more-or-less willingly, this one does so through sheer torture. This is all the more disturbing because at one point Bofur manages to gain control of this troll and delightedly uses him as a weapon in the same fashion, directing him with the reins and hooks.

Apart from such scenes, there are numerous new moments where decapitations and amputations are copiously meted out, often in humorous fashion. In one scene Thranduil’s battle elk scoops up eight or so orcs, and the Elven King beheads them all with a single sweep of his sword.

The chariot drawn by large rams has blades sticking out from the hubs of its wheels, and these provide the opportunity for much carnage, as when one cuts off a large orc’s legs and it staggers about on the stumps of his thighs or when a row of trolls are rapidly decapitated as the the chariot bounces past them.

I watch and write about movies for a living and have been exposed to a great deal of cinematic violence, but such scenes as these seem particularly out of place to me in a series aimed at an audience intended to include young people.

More echoes of LOTR

In the third entry, I discussed what I consider a serious problem with The Hobbit: the tendency to copy so many elements from LOTR.

Most crucially, I think, instead of using these already established characters in Desolation or just sticking more closely to the book, the filmmakers have introduced many new elements that are essentially diminished versions of characters and events in LOTR. That strikes me as a bad idea and perhaps really does betray a lack of inspiration. Already fans of the LOTR films have complained that so many echoes of LOTR appear in Desolation. Worse is to come, though. When people view LOTR as part of a series of six parts beginning with The Hobbit, they will end up seeing things in LOTR as echoes of Desolation. The result will be to rob LOTR of some of its originality and effectiveness.

Take Tauriel. She’s a pleasant, admirable character, with a stubborn, headstrong streak that keeps her from being bland. Evangeline Lilly’s performance strikes me as excellent. A lot of fans worried about her inclusion in the film but came to like her. They seem to see her as blending well into the world of the film. But there’s a reason for that. She does come from the world of LOTR.

Was it really a good idea to add a major character who’s basically a blend of Arwen and Eowyn? Doesn’t she make both of those characters less distinctive?

Similar things happen in Five Armies. Bombur blows a big horn outside Erebor during the Battle, just had Gimli had done to signal the big charge out of Helm’s Deep in The Two Towers (in a more impressive composition).

Yes, one takes place in daytime and is seen in low angle, the other at dawn and from above, but still.

Or take the appearance of the Eagles, which in both films drift out of the bright clouds in the background, their leader carrying a wizard. (Radagast does not appear at all in the book, let alone as part of the battle.)

The berserker troll that butts his head into the protective wall at Dale recalls the similar Uruk Hai with a torch who dived into a drain tunnel at Helm’s Deep, sacrificing himself to set off an explosive and create a similar entryway for the attacking army of orcs.

In addition, there’s the scene of the arming of the men and boys in Dale echoing the one in Helm’s Deep. Or Dale in flames, see from above and looking very like Minas Tirith in a similar situation.

I wish I could give the filmmakers the benefit of the doubt and say that these echoes are attempts to create motifs that would knit the two films into a single, unified tale. That’s not the effect of them, however. Aren’t these just repetitions without any real connections? Why would things so often happen in the same way? Doesn’t it distract from the drama at hand to keep thinking back to when we’ve seen something like this before? Wouldn’t we’d rather be seeing something new and original?

There should instead be more echoes like the one mentioned above, between the death of Smaug above a lake of fire and the scene where Thorin’s hallucinations are staged on a similarly glowing golden floor. That’s the way to create a rich narrative, and that comparison resembles nothing in LOTR–except perhaps the shot of Gollum, also seen from above, falling into the pit of lava. Whether or not the similarity of the two shots in Five Armies were intended to echo the Gollum one, it’s a reasonable comparison to make.

I haven’t yet tried the experiment of watching all six parts straight through, The Hobbit and then LOTR, to see how they work as a complete serial. More than ever I fear that the result will be to diminish LOTR, which is clearly the better of the two by a long way.

Basically I do not think that many of The Hobbit‘s problems result from the splitting of the adaptation into three rather than two parts. Done in service to the original book, it could have worked. Rather, those problems stem from a fundamental mistake made by the filmmakers.

They decided to adapt The Hobbit into an adult story with the same sorts of somber moments and terrors that LOTR contains. I basically agreed with that decision in a previous entry, saying this was now Peter’s Hobbit. But given how far he took all this–with the overextended battles, the urge to interject grotesque humor into serious situations, and the extra characters who turn Bilbo into a supporting player in his own tale–I believe he should have done what Tolkien did: let the two books (or films) be different. Let one be aimed at children—less violent, simpler, more humor—and the other be aimed at adults.

So what if the two aren’t consistent with each other? Generations have read Tolkien’s two novels and noticed that they are essentially in different genres and simply accepted that. The problem has been compounded by the fact that so much that happens in The Hobbit is copied so closely from LOTR. Now that we have every bit of the second trilogy, I’m afraid I must conclude that yes, this Hobbit is chubby but also off-balance and padded.

My “A Hobbit is chubby” phrase refers to the fact that Tolkien’s Hobbits are all to some degree chubby. This is not the case with three of the four main Hobbits in LOTR, nor is it true of Bilbo. Still, given the controversy over the added length of the film adaptation, it was impossible to resist the reference.

Although much has been made of the idea that the two trilogies are the same length, in that they are three parts each, it’s worth pointing out that the extended version of The Hobbit (8 hours 52 minutes) totals an hour and a half shorter than that of The Lord of the Rings (11 hours 22 minutes). Over such a span it may not seem like much, but it’s the equivalent of a shortish feature film.

In the mood for WKW

In the Mood for Love (2000).

DB here:

For quite a while, many of us have been looking forward to a book called Wong Kar-wai on Wong Kar-wai, a collection of interviews conducted by Tony Rayns. Alas, that is evidently never to be, for reasons that Tony hints at in his new BFI monograph on In the Mood for Love. Bits of those interviews make their way into the book anyhow, along with information and ideas reflecting Tony’s unique access to Hong Kong’s illustrious filmmaker. All lovers of WKW will want this energetic, accessible study.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

The thankless task of providing a detailed synopsis is carried off briskly, sustained by many explanations of culturally specific references. We learn of the daibaitong, the open-air restaurant where both Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan stop for a night’s noodles. We’re led to notice the inside joke about wuxia novels’ outlandish plots, as well as the changing of seasons as reflected in costumes. The synopsis is also sprinkled with critical-analytical points about parallels between the characters, relationships merely hinted at, and cross-references among the kindred films.

The talk around the Jet Tone office during the production of In the Mood for Love was of Chow Mo-wan setting out to seduce Mrs. Chan as a prelude to abandoning her: an act of wilful emotional cruelty intended as a revenge for being cuckolded himself. This inference is nowhere evident in the film as released, so Wong perhaps recycled the idea into Chow’s smiling rejection of a romance with “taxi-dancer” Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi) in 2046–although that rejection is itself a gentler replay of the playboy’s treatment of Carina Lau’s needy hooker Lulu, also known as Mimi, in Days of Being Wild.

There’s also quite a lot about the soundtrack, with close attention to the recurring melodies in the score and to the shifts between Cantonese and Shanghai in the dialogue.

After the synopsis comes an analysis/interpretation. When the central couple reenacts their spouses’ affair, Tony suggests they’re testing the limits of their own inhibitions. He stresses the distinctiveness of Wong’s style, from its cinematic punctuation (the synopsis has emphasized the patterns of fades and straight cuts) to its handling of time–especially the strategically opaque narration, its “ostentatiously selective presentation of the action.” Of course the guilty spouses are never fully shown, but Tony also traces how time is skipped around via flashforwards and ellipses, sometimes barely noticeable ones. He points out how one cut relies on false continuity. Smoking alone in room 2046, Chow hears a knock on the door. Cut to a long shot of Mrs. Chan at the door–but she’s leaving.

We’ll never know what transpired during her visit. This exemplifies Wong’s “discontinuity in continuity”; flowing music, gentle tracking shots, and slight slow motion create a smooth surface that can conceal crucial information.

Tony has more to tell than the BFI format can squeeze in. I’d like more on the way quite disjunctive techniques fit into the film’s stylistic sheen. Wong deploys off-center framings, judicious use of depth in apparently real apartments, and variations in lighting among Hong Kong, Singapore, and Kuala Lampur. Tony’s hunch about continuity covering discontinuity might be extended to these aspects, and of course insider information on these matters would be welcome. I also wonder: Could there have been a hotel at the period boasting twenty stories? My Hong Kong friends say not. Tony argues that Wong’s films aren’t deeply political, but he was willing to violate plausibility to invoke the fateful year when HK becomes integrated into China.

Calm and ingratiating, the monograph is disarmingly personal as well. (How many books on a director start by noticing that the author has been dropped from a Christmas-card list?) It’s agreeably contrarian too. Tony teases academics, claiming at one point that the clock shots are “self-parodies” and “sucker bait” for critics who believe that Wong is the great cineaste of time. The book ends with a miscellany of observations about actors in bit parts, filmic offshoots of the project, and a little gossip. In all, reading In the Mood for Love gets you in the mood for In the Mood for Love.

Tony Rayns tells more in interviews on the Blu-ray disc of In the Mood for Love available from Criterion. That version of the film’s color seems far superior to other DVD versions I’ve seen, some of which have a dim, brownish cast. This is a hard film to replicate, though, as I found in taking 35mm frames: the tonal range is extraordinary, and your choice is often between exaggerating and lowering contrast.

Tony makes reference to the famous epilogue of Days of Being Wild that shows Tony Leung Chiu-wai, an apparently brand-new character cryptically introduced in this scene. The shot implies that there’ll be a sequel, and Wong has occasionally suggested the possibility. But there is a version of the film that includes a prologue showing the same character dressing to go out. Along with that scene is a sensuous passage in an underground gambling parlor. The sequence looks forward to imagery in In the Mood, including a sinuous shot of a woman ascending a staircase. If Wong chopped off the prologue to create the version of Days we have, he perversely left the dangling epilogue to tantalize us. For more about this “lost” version see my entry “Years of Being Obscure.”

I analyze Wong’s career, along with In the Mood for Love, in Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and I talk about The Grandmaster (which Tony considers a weak entry) here. I offer thoughts as well on Ashes of Time Redux. This project was the casus belli for Tony’s departure from Planet WKW. “The sometimes hair-raising tales of my experiences with Jet Tone will have to wait for another time.” What if we can’t wait?

In the Mood for Love.

![Dain speaks to Elves [extra] p 2 back](https://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/Dain-speaks-to-Elves-extra-p-2-back.jpg)