Archive for 2016

Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO

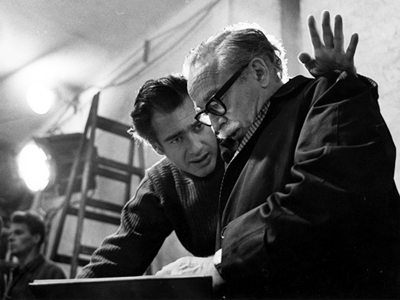

Bryan Cranston as Dalton Trumbo; John Frankenheimer and Dalton Trumbo.

DB here:

Who better to comment on the historical implications of Jay Roach’s Trumbo than our friend and collaborator on Film Art, Jeff Smith? He’s not only an expert on film sound, as he showed in his guest post on Brave, but he has written a book on the Hollywood blacklist. Jeff offers these observations on the film.

Last week, I was delighted to see that Bryan Cranston received an Oscar nomination as the star of Trumbo. Throughout the month of November, I was “johnny-on-the-spot” for local media interested in covering the new biopic about Dalton Trumbo. The story had a local angle. In 1962, Trumbo donated a large collection of scripts, notes, contracts, photos, and business correspondence to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Since then, scholars interested in the Hollywood blacklist have been making pilgrimages to Madison to probe Trumbo’s collection as well as the papers of five other members of the Hollywood Ten (Albert Maltz, Ring Lardner Jr., Herbert Biberman, Samuel Ornitz, and Alvah Bessie.)

I had done a lot of work with the collection, so I could do interviews with WMTV, WISC, The Wisconsin State Journal, and University Publications. Unfortunately I had not yet seen Trumbo, the Jay Roach film based upon Bruce Cook’s 1977 biography. I could talk about Trumbo’s life and career and the buzz I’d heard about the movie, but until it played Madison, I had to stay mum about the movie itself.

After a couple of weeks in distribution in limited release, Trumbo went wide just before Thanksgiving. Now that I’ve seen it, I am delighted to report that Trumbo merits every bit of the hype that surrounded it. To my mind, it is the best fictional film about the blacklist that Hollywood has yet produced.

Buoyed by a standout performance by Cranston, Trumbo is fast-paced and funny, and rather nimbly summarizes many of the political and industrial issues that led to the institution of the blacklist in 1947. It also showcases the effect that “unemployable” writers working on the black market had in undermining the rhetoric of the blacklist throughout the Cold War period. It became hard to say with a straight face that you were protecting American screens from the taint of Red propaganda when films secretly written by Communists were winning awards and topping the box office.

I was struck by some of the choices made by Roach and screenwriter John McNamara in bringing Trumbo’s story to the big screen. Although Trumbo’s career has been well documented by film scholars, Roach and McNamara faced the same challenges in adapting Cook’s biography that any filmmaker does in transforming a literary property into a classical narrative structure. How do you make Trumbo an active, goal-oriented protagonist despite the fact that he was the victim of historical circumstance? How do you deal with the welter of historical actors and subplots that populate Cook’s biography? How do you boil down a complex historical situation into a clear, transmissible narrative?

Witnesses, friendly and otherwise

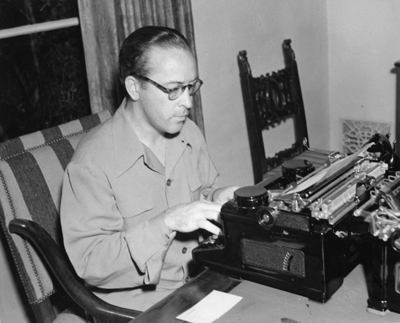

Dalton Trumbo at work.

Like many contemporary Hollywood biopics, Trumbo doesn’t try to convey the full sweep of its subject’s quite colorful life. It omits reference to young Dalton’s Christian Scientist upbringing, his early toils in the Davis Perfection Bakery, or even the publication of his first story in 1933. Indeed, the film also makes only offhand references to Trumbo’s early achievements as a novelist and screenwriter. These are briefly acknowledged near the film’s start through a series of shots in Trumbo’s office at the Lazy-T Ranch that reveal his award for Johnny Got His Gun and his Oscar nomination for Kitty Foyle.

Instead the film focuses on the period of Trumbo’s career during which the screenwriter became one of Hollywood’s sacrificial lambs at the altar of HUAC’s anti-Communism. When the film begins in the mid-forties, Trumbo was the most highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood, earning $75,000 per script. In today’s currency, that amounts to about $800,000 per picture, a remarkable sum for someone under studio contract.

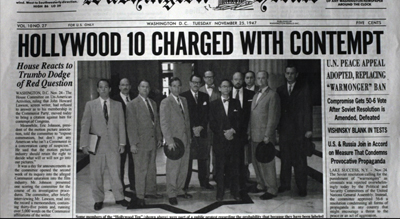

Just a few years later, Trumbo would appear as an “unfriendly witness” during hearings conducted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in October of 1947. As a result, he’d eventually be convicted of Contempt of Congress charges and sent to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky.

Although HUAC was concerned about the potential subversion of American screen content, it was not, in fact, illegal to be a member of the Communist Party. It was, however, a criminal offense to advocate for the overthrow of the American government according to the provisions of the Alien Registration Act (aka the Smith Act) passed in 1940.

About six months after HUAC concluded their hearings on Hollywood, a dozen Communist Party leaders were indicted for Smith Act violations. Defendants insisted that political change in America could be accomplished through democratic process and constitutional principle. But prosecutors claimed these statements couldn’t be trusted since Communists employed “Aesopian language” and therefore did not really mean what they said. The attack proved successful and effectively criminalized membership in the Communist Party as a result. Since any individual’s denial of revolutionary rhetoric would be viewed with suspicion, you were likely seen as guilty of the Smith Act if you simply owned a copy of Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto.

Even before the Foley Square trials, as they came to be known, many of the Communist Party’s rank and file, including the Hollywood Ten, also feared that they would be prosecuted on similar grounds if they admitted their membership. This proved to be one factor that favored the Ten’s failed “first amendment” defense. True, they risked getting cited for Contempt of Congress. But that had the prospect of looking more dignified than simply being hauled off in cuffs on Smith Act charges.

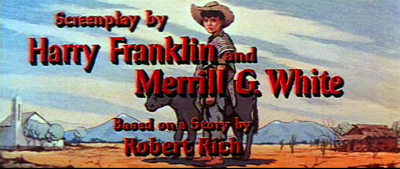

When he returned from prison, Trumbo encountered an industry that wanted him, but not his name on the credits. Producers recognized his talent, and he continued to write through the circuitous network of fronts and pseudonyms. Trumbo would win two Oscars for his work as a black market screenwriter: one for the Gregory Peck/Audrey Hepburn classic, Roman Holiday (below) and another for a Disneyesque “boy and bull” story, The Brave One.

By the end of 1960, Trumbo’s name would once again grace movie screens as the credited screenwriter on Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus and on Otto Preminger’s Exodus. This moment essentially ended what remained of the Hollywood blacklist. In moving from the limelight to the shadows and back again, Trumbo’s life had the kind of plot arc that Hollywood loves. It’s a story of redemption in which the hero overcomes overwhelming odds to regain the professional respect and recognition he’d been denied.

Although all of this suggests that Trumbo is a pretty conventional biopic, it’s quite unconventional in its treatment of the blacklist. As the late Jeanne Hall noted years ago, Hollywood’s representation of this dark chapter of its past was surprisingly evasive, getting on the right side of history but for all the wrong reasons.

Bad Faith in Appleton

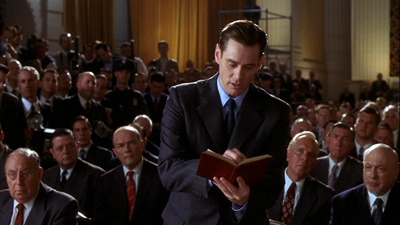

The Majestic (1999).

In titles like The Way We Were, The Front, and Guilty by Suspicion, filmmakers pulled a “bait and switch.” They substituted obvious cases of injustice for the much messier questions posed about HUAC’s abrogation of basic civil rights protections. The Hollywood Ten tried to defend themselves on First Amendment grounds, questioning whether HUAC itself had the right to invade their privacy or to limit their freedom of assembly. But in most of these earlier films about the blacklist, HUAC’s inquiry eventually entangles someone who was never a member of the Communist Party. In The Way We Were, the WASP-y Hubbell comes under suspicion for his relationship with the Jewish radical, Katie. In The Front, Howard comes under suspicion after selling black market scripts by Communist writers under his own name. Both of these instances present obvious cases of individuals wrongfully accused. They recruit our sympathies for characters that suffer as a result of HUAC’s tactics, but gloss over more fundamental questions about whether someone should be denied employment on the basis of their political beliefs.

No film, however, displays the equivocation evident in previous representations of the blacklist as vividly as Frank Darabont’s The Majestic. The protagonist, Peter Appleton, is a Hollywood screenwriter who has just been named by the committee. Distraught, he takes a drive out of Hollywood, but has an accident en route. Suffering from amnesia, Appleton finds himself in the small town of Lawson, California where is mistaken for Luke Trimble, a soldier killed in action some nine years earlier. Appleton becomes immersed in the Lawson community, helping his “father,” Harry, restore the small town theater that gives the film its title. Prompted by a combat film shown in the Majestic, Appleton regains his memory, and confides the truth of his situation to his new girlfriend. After his car is discovered, federal agents give Appleton a summons to testify about his Communist affiliations.

During the climax, Appleton appears before HUAC with the aim of clearing himself. Congressman Elvin Clyde confronts Appleton with evidence that he attended a meeting of the “Bread Instead of Bullets” club. Appleton pleads innocence, saying he only went because he was a “horny, young man” seeking to impress his date, Lucille Angstrom. Just as he is about to deliver his prepared statement purging himself of Communist associations, Appleton changes his mind. Instead he gives an impassioned speech that cites his First Amendment rights and denounces the investigation as a betrayal of America’s real ideals. Appleton saunters out of the hearing to the loud applause of onlookers. Yet Appleton’s lawyer later tells him that Angstrom is currently a CBS producer on Studio One, and his reference to her as a member of the Communist front organization is viewed as cooperation with the Committee.

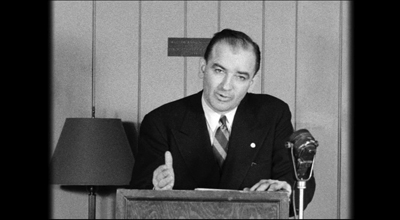

In The Majestic’s civic fantasy, the committee hearing revives the “wrongly accused” trope seen in earlier blacklist films. Worse, it shows its hero successfully using the First Amendment legal defense that had spectacularly failed when the Hollywood Ten used it during the 1947 hearings. Moreover, because Appleton is a political naïf, his inadvertent naming of names redounds to his benefit. Given the film’s hopelessly confused politics, perhaps there is unintentional irony in the fact that Appleton is also the name of the Wisconsin hometown of Senator Joseph McCarthy (below), the man synonymous with the Cold War’s anti-Communist campaign.

Trumbo, in contrast, doesn’t pull any punches. The film condemns HUAC’s activities not because it was prone to wild, unproven accusations like those of McCarthy, but rather because the very nature and essence of its inquiry was itself an abuse of power. The movie does nothing to deny Trumbo’s guilt. Indeed, the real-life Trumbo freely admitted it. In the 1976 documentary Hollywood on Trial, Trumbo described his reaction to his trial thusly: “As far as I was concerned, it was a completely just verdict. I had contempt for that Congress and have had contempt for several since.”

Yet, while not excusing Trumbo’s actions, the film dramatizes the debilitating effects of being blacklisted, both in his professional and personal life. The burden of Trumbo’s black market work put a strain on his marriage and his family, all of whom were enlisted to perform services he himself could not do publicly.

The blacklist: More than Red-baiting

Besides providing a more accurate picture of Red-baiting and its effects, Trumbo also proves remarkable in making passing reference to some of the important secondary causes that eventually led to the blacklist. An early scene, for example, shows Trumbo (above) on a picket line during the vituperative Congress of Studio Union strikes that took place in 1945. Film historian Jon Lewis argues that one reason for the studio’s cooperation with HUAC’s investigation was that it served their interests in their long-term relationship with Hollywood’s craft guilds. Once Communists within the film industry’s labor unions became targets of government scrutiny, only the more moderate factions remained. Whether or not HUAC’s investigation was a direct cause, Hollywood did not experience another strike until more than four decades later.

Trumbo refers to another cause of the blacklist: anti-Semitism. Although it was something of a stereotype, Communists were popularly associated with European Jews. In fact, when Warner Bros. released I Was a Communist for the FBI in 1951, several moviegoers wrote studio head Jack Warner complaining that the film repeated the lie that all Jews were Communists. Said one Julius Newman of Roxbury, Massachusetts: “I demand that this dangerous, rotten, and libelous bit of propaganda be withdrawn immediately before some Jewish mother somewhere, gets her son’s skull cracked for Mother’s Day.”

The perception that anti-Semitism was an underlying cause of the blacklist was aided by the fact that three of the Committee were members of the Ku Klux Klan at the time of the 1947 hearings, including the Chair, J. Parnell Thomas. Moreover, in a speech before the House of Representatives, another HUAC member, Mississippi Democrat John Rankin, attacked members of the Committee for the First Amendment, who had lobbied on behalf of the Hollywood Ten. Rankin claimed that certain performers were suspect because their Anglicized names hid their actual Jewish origins:

One of the names is June Havoc. We found that her real name is June Hovick… Another one is Eddie Cantor, whose real name is Edward Iskowitz. There is one who calls himself Edward Robinson. His real name is Emanuel Goldenberg. There is another here who calls himself Melvyn Douglas, whose real name is Melvyn Hesselberg.

Screenwriter John McNamara wrote a similar speech for Trumbo, but placed it in the mouth of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. When MGM boss Louis B. Mayer reminds Hopper that the legal situation was complicated by the fact that several of the Hollywood Ten had contracts, she responds:

Then how about I make crystal clear to my thirty-five million readers who runs Hollywood and won’t fire these traitors? How about I name names, real names? Like yours, Lazar Meir; or Jack Warner, Jacob Varner; Sam Goldwyn, Schmuel Gelbfisz.

The presence of Hedda Hopper in Trumbo hints at a third underlying cause of the blacklist: the role of the trade press and gossip columnists, who prosecuted and enforced it. Hopper was not alone in this endeavor. Publishers like Billy Wilkerson of The Hollywood Reporter and columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan “cheered” HUAC’s efforts from the sidelines. They also helped the enforcement of the blacklist once it was instituted, calling public attention to the surreptitious presence of banned writers on the black market.

All of these elements in Trumbo’s script make it a richer, more sophisticated depiction of the Hollywood blacklist than that offered by its predecessors. They also remind us that its operations were about more than just politics. Once the blacklist was established, studio bosses gained the upper hand in their dealings with labor, gossipmongers used rumor and accusation to fill column inches and sell papers, and anti-Semites exploited the common association of Communism and Jewish intellectuals to thwart activism among progressives, including those in the Civil Rights movement.

In sum, Trumbo offers a more nuanced sense of the various factors at play at the time of the blacklist than virtually all of its cinematic predecessors. This makes it all the more surprising then that the film nonetheless rewrites history in other ways. In an effort to both streamline and personalize its protagonist’s story, Trumbo invents new characters, revises the order of historical events, and shorts the achievements of other black market screenwriters who also contributed to the blacklist’s ultimate demise.

The eleventh member of the Hollywood ten

Although most film audiences expect that movies will generally portray historical events with some degree of accuracy, Hollywood cinema rewrites history all the time. Despite the fact that this is common practice, some films that take such liberties are hurt by negative publicity, especially around awards time. Recall the controversy surrounding Selma’s depiction of President Lyndon Johnson as an opponent of Martin Luther King’s famous march rather than as a “behind the scenes” ally. Some believe that the loud complaints coming from the LBJ camp cost director Ava DuVernay an Oscar nod.

Trumbo is no exception to this principle, even though it has been unusually forthright about the changes made to the historical record. My spidey senses were alerted to this during the movie when they introduced Louis CK’s character as “Arlen Hird.” I’d never heard of Arlen Hird.

Both in interviews and in an article in the New York Times, screenwriter John McNamara has acknowledged that Hird is a composite character, whose traits and experiences are based on five other members of the Hollywood Ten. Louis CK, for example, physically resembles the real-life Alvah Bessie, who, like the character, was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish civil war.

Moreover, when Hird is in prison, he hears a radio broadcast of Edward G. Robinson’s “friendly” testimony. Robinson calls him “the top fellow who they say is the, uh, commissar out there,” a swipe that blacklist historians would immediately associate with John Howard Lawson. And sadly, like Samuel Ornitz, Hird dies after battling cancer, having never seen the blacklist come to its ignoble end.

As Nicolas Rapold observes in the Times, Hird is meant to stand in for other Communist screenwriters whose attitudes were more doctrinaire than Trumbo’s. Yet I believe the real purpose of using a composite character is to simplify the historical record to make it more digestible for the viewer. Rather than tracing out Trumbo’s relation to all of the eighteen other “unfriendly witnesses” subpoenaed by HUAC, McNamara opts to consolidate them into a single character. Such a decision makes some intuitive sense, since viewers would be hard pressed to keep tabs on a parade of many characters. By creating Hird as a composite, Trumbo’s interactions with him gain vividness and salience.

Still, McNamara’s narrative technique is merely one approach among a larger menu of options, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses. He could have treated the Hollywood Ten as a group protagonist, who all share the same goal in legally challenging HUAC’s authority. Such a gambit, though, would have displaced Trumbo from the center of the story early on. That decision would have weakened the causal motivation behind his later emergence as a black market crusader.

Alternatively, McNamara could have dramatized Trumbo’s individual interactions with Bessie, Lawson, and Ornitz, et.al., using a superimposed title to identify each one. The gain in accuracy, though, would likely mean a loss of dramatic clarity and a mildly more self-conscious style of narration. More important perhaps, it also would make for a less emotionally engaging story. The film shows Hird confiding in Trumbo at the Lazy-T ranch, participating in the Ten’s legal strategy, serving his prison term, and undergoing surgery for lung cancer. The accumulation of these details provide for a more fully fleshed out character. There’s also the opportunity to feel empathy for Hird’s children at his funeral, an effect that couldn’t have been as focused if Hird’s problems were scattered among separate individuals.

None of this is meant to suggest that McNamara absolutely made the right choice in deciding to treat so many members of the Ten as a composite. Rather, it is simply the recognition that such a technique is the result of a deliberate choice and further that one creative decision can lead to a cascade of others. Had McNamara stayed doggedly faithful to the historical record, Trumbo would have been a different film, but perhaps not a better one.

Perhaps we should recognize that screenwriters often must adapt historical narratives in the same way that they adapt literature. And the same sorts of questions about fidelity will bedevil us as when films change details of our favorite novels and stories. Rather than being dogmatic in expecting that historical films stick close to the facts, maybe we simply should ask whether the film is faithful to the spirit of the historical record, especially when its creators are so open and honest about the changes they made. Such a stance would at least recognize the difficulties faced by screenwriters in balancing the weight of classical narrative conventions against the strict measure of historical accuracy. If, as many screenwriters argue, films differ from literature in their emphasis on conflict and action, then the decision in Selma to treat LBJ as an obstacle to Martin Luther King’s goal makes a certain dramatic sense. Here again, one can debate the merits of that creative choice. But at least we do so with a fuller understanding of why such choices are made in the first place.

Get me rewrite!

Besides creating composite characters, McNamara rewrites history in other ways. Perhaps the most obvious is when he creates a scene in prison between Trumbo and HUAC chair, J. Parnell Thomas, which never actually happened. True, Thomas was convicted on corruption charges and was sent to federal prison. But he served his term in Danbury, Connecticut rather than Ashland, Kentucky where Trumbo was incarcerated.

In this case, the real-life story proves more entertaining than what appears in the film. While at Danbury, Thomas encountered two other members of the Hollywood Ten – Lester Cole and Ring Lardner, Jr. — serving their time on Contempt of Congress charges. Upon seeing Thomas working in the prison yard, Cole made a wisecrack that led the former HUAC chair to respond, “I see that you are still spouting radical nonsense.” Cole’s sharp retort: “And I see you are still shoveling chicken shit.”

In other cases, McNamara revises the chronology of events. In the film, Trumbo first meets with the King Brothers, Frank and Hymie, just after he is released from prison. In reality, Trumbo started working for the King Brothers just weeks after his HUAC testimony. Almost immediately after being suspended by MGM, Trumbo did black market work on the screenplay for the King Brothers’ cult classic, Gun Crazy, using fellow writer Millard Kaufman as a front. With Kaufman serving as intermediary, the Kings likely did not know of Trumbo’s involvement. But the brothers began working directly with Trumbo shortly thereafter. In fact, Frank King personally visited the Lazy-T ranch just prior to the Trumbo’s departure for prison, offering to pay him $8,000 to write the script for Carnival Story.

Trumbo coyly acknowledges the screenwriter’s contribution to Gun Crazy by featuring posters of the film in several shots. But by revising the historical circumstances of Trumbo’s first involvement with the Kings, the film more or less denies him actual credit attribution, ironically engaging in the same sort of opportunism displayed by the producers who surreptitiously hired him.

McNamara’s most significant changes to blacklist history, though, involve omissions. Trumbo’s Oscar victory for The Brave One is well documented and the episode – both in the film and in real-life – neatly captures his role as industry gadfly. But the same year that the mysterious “Robert Rich” won the Academy Award for Best Original Story, Michael Wilson also was nominated for a project for which he was publicly denied screen credit.

Wilson had completed a first draft of Friendly Persuasion for director Frank Capra in 1946, but no film was made from the script until producer/director William Wyler took over the project in 1955. When it came time to determine the screenwriter credit, Wyler suggested that it go to Robert Wyler and Jessamyn West for their extensive revisions, including many rewrites completed on set during shooting. When Wilson became aware of this, he immediately protested Wyler’s decision and forced arbitration by the Screen Writers Guild. The Guild ruled in Wilson’s favor, but also reminded the film’s distributor, Allied Artists, that they could legally deny credit to any screenwriter who had failed to clear himself before HUAC. When Friendly Persuasion was released in 1956, its only writing credits read “From the Book by Jessamyn West.”

Despite a good deal of press coverage of the dispute, the incident might have been a mere blip on the cultural radar if not for the 1957 Oscar nominations. When they were announced, a film with no credited screenwriter unexpectedly received a nomination for a screenwriting award. And with public acknowledgement of Wilson’s contribution to Friendly Persuasion more or less verboten, the text of the nomination simply said the writer was ineligible under Academy rules.

Worried that a public victory by a blacklisted writer would give the industry a big ol’ black eye, the Academy reportedly instructed Price Waterhouse to excise the nomination from the Oscar ballots that were sent to voters. Yet, even though the Academy essentially rigged the vote against Wilson, Groucho Marx offered an incisive quip about Wilson’s situation at the Writer’s Guild Awards banquet held about two weeks before the Oscars. Said Groucho, “The Ten Commandments. Original story by Moses. The producers were forced to keep Moses’s name off the credits because they found out he had once crossed the Red Sea.” Given all the effort that went into preventing Wilson from receiving the award, Trumbo’s Oscar win as “Robert Rich” must have tasted even sweeter. The award was given in absentia by Deborah Kerr, and Jesse Lasky, Jr. accepted it.

Moreover, the Rich incident was hardly the last humiliation that the Academy would suffer. The very next year novelist Pierre Boulle received a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination for The Bridge on the River Kwai, which was based on his book. But Boulle had been a front for Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, who had taken the assignment as black market work for producer Sam Spiegel. When Boulle’s name was announced as the winner, the novelist was nowhere to be found. Instead, Kim Novak accepted the award on his behalf. But insiders knew exactly why Boulle was absent. As someone who wrote and spoke in French rather than English, his stumbling acceptance speech would have exposed the hypocrisy by which Foreman and Wilson were denied an award that they merited. (Sadly, neither Foreman nor Wilson would live to see their work duly recognized. In 1984, the Academy posthumously recognized them as the true authors of Kwai’s screenplay.)

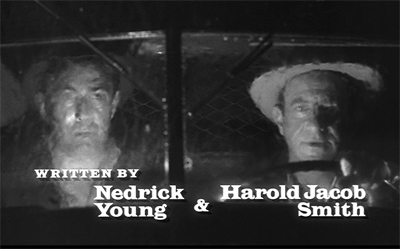

Nathan E. Douglas = ?

The original credits sequence of The Defiant Ones (1958) listed Nedrick Young as a coauthor under his pseudonym Nathan E. Douglas. He appeared in a bit part coinciding with his credit listing, along with coauthor Smith, in the cab of the truck. Video versions such as this have restored his name.

Things didn’t end there. The Oscar nominations in 1959 saw yet another brewing controversy regarding eligibility of a black market scribe. The writing team of Harold Jacob Smith and Nathan E. Douglas earned a nod for Best Original Screenplay for The Defiant Ones, even though the latter was a pseudonym for blacklisted writer Nedrick Young. If anything, Young’s participation in the making of The Defiant Ones was signaled by producer-director Stanley Kramer’s giving him a notable cameo in the film. During the opening credits, Young and Smith are both seen as prison guards riding in the front seat of a truck used to transport convicts. In a rather coy gesture, when the film’s writing credits are shown, Young’s pseudonym “Nathan E. Douglas” is superimposed over the man himself. Even though the general public didn’t know Young from Adam, his cameo made his participation an open secret in Hollywood.

During awards season, Young as “Nathan Douglas” collected a lot of hardware, including awards from the New York Film Critics Circle and the Writer’s Guild of America. With the nominations imminent, leadership within the Academy recognized that a third straight public relations disaster was in the offing. Just before Christmas in 1958, former Academy president George Seaton approached Young and Smith seeking assistance in overturning the Academy bylaw prohibiting blacklisted personnel from eligibility for awards. For his part, Trumbo himself stayed abreast of the situation and even rescheduled a media interview order to avoid fanning any flames of opposition from within the Academy.

On January 15, 1959, Seaton, Young, and Trumbo all got their wish as the hated bylaw was officially rescinded, passed by the Academy’s Board of Governors with near unanimous support. Two days later, Trumbo confirmed to newsman Bill Stout that he was, indeed, Robert Rich. On Oscar night a few months later, Young enjoyed the spotlight in a way that had been denied his predecessors. And when The Defiant Ones won the Oscar for the Best Story and Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen, Young strode to the podium along with Smith and offered a humble thank you. Ward Bond, one of John Wayne’s allies in the Motion Picture Alliance for American Ideals, observed: “They’re all working now, all these Fifth-Amendment Communists. We’ve just lost the fight. It’s as simple as that.”

Where does all of this backstory fit into the story told in Trumbo? As it turns out, nowhere. In choosing to concentrate on Trumbo’s story, the movie keeps all of this rich contextual material offscreen. As is often the case, the historical realities surrounding the end of the Hollywood blacklist were much denser, messier, and more complex than what can easily fit into a standard two-hour film. Classical Hollywood narrative, with its emphasis on goal-orientation and clearly motivated, causally linked events, tends to nudge screenwriters away from the sprawl more often found in novels or television miniseries. In the case of Trumbo, screenwriter John McNamara likely opted for the virtues of clarity and concision. He concentrated only on those incidents that directly involved the titular character, eliminating or minimizing anything that would detract from that narrative focus.

That being said, the creative choices of McNamara and director Jay Roach are, above all, choices. The screenplay for Bridge of Spies, for example, manages to convey something of the complex bilateral negotiations that linked the downing of U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers with the seemingly unrelated espionage case of KGB officer Rudolf Abel. One could imagine Roach and McNamara devising very brief scenes of Wilson, Foreman, and Young in their Academy imbroglios. Or alternatively, the film might have included Trumbo’s voiceover reading the text of his actual letters to Wilson, many of which commented on the perpetually changing conditions of the black market. As before, the inclusion of such material wouldn’t necessarily make Trumbo a better film. But it would make it a different one.

Although Dalton Trumbo led the fight against the blacklist, often using the industry’s greed, hypocrisy, and mendacity against itself in the process, my brief synopses of these other screenwriters’ Academy Award travails show that he was not alone. Many individuals taking small incremental actions led to the blacklist’s end. It wasn’t smashed; it crumbled through erosion. The fact that one of Hollywood’s “untouchables” was able to openly accept a major industry award made open screen credit a logical next step. Dalton Trumbo happened to be the lucky individual to regain his name without having to bow and scrape before HUAC. But even he knew it could just as easily have been Nedrick Young. Or Michael Wilson. Or Albert Maltz.

Come Oscar night on February 28th, if Bryan Cranston is lucky enough to hoist the Best Actor prize above his head, it will be a fitting tribute to a man whose struggles with this same institution helped to define him and his era. Yet an Oscar victory would also pay tribute to all those whose stories have not reached the screen, but whose grit and determination made Trumbo’s triumph possible. And Mr. Cranston, if you get to deliver that acceptance speech, be sure to remember all those unsung heroes that joined Trumbo in the fight.

Trumbo is based on Bruce Cook’s biography, which was first published in 1977. Readers should also check out Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo’s massive, exhaustively researched new biography, Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical. Ceplair is also the co-author, with Steven Englund, of the standard work on the Hollywood blacklist itself, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics and the Film Community, 1930-1960. My book, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds, also considers Trumbo’s contribution to Spartacus.

Trumbo’s collection of correspondence, speeches, business papers, scripts, and photographs is held at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. A rich sampling of material from it is available here. Several of the photos in this entry come from the WCFTR collection. Go here to listen to excerpts from his HUAC testimony.

Excerpts from John Rankin’s infamous speech about Jewish actors in Hollywood can be found in Gordon Kahn’s Hollywood on Trial: The Story of the Ten Who Were Indicted. Trumbo himself commented on the role of anti-Semitism in HUAC’S investigations in The Time of the Toad: A Study in Inquisition in America.

Franklin Leonard interviewed John McNamara last November about his work on Trumbo for his Black List Table Reads podcast. Nicolas Rapold offers a useful guide to the individuals profiled in Trumbo, including its composite characters. If you’re interested, you can see actual footage of the announcements of various screenwriting awards at the Oscar ceremonies of 1957, 1958, and 1959.

For more on how adaptation works, see the thirteenth chapter of the new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming next week. That chapter is available for courses as an add-on to both the printed edition and the McGraw-Hill electronic edition.

Trumbo.

They see dead people

DB here:

Continuity editing was one of the great collective inventions of filmmakers. In the ten years after it crystallized in Hollywood around 1917, it was adopted around the world. The technique has hung on a surprisingly long time, rather like geometrical perspective in pictorial art. It’s so powerful that it’s hard to escape.

It’s powerful partly because it’s adaptable to a lot of narrative situations. It provides filmmakers what we can call a set of stylistic schemas, or routine patterns, that can be adjusted in various ways. Analytical cuts that take us into or back from the action, shot/reverse shots and eyeline matches, over-the-shoulder framings (OTS), and slight camera movements that set up reestablishing shots: these straightforward schemas can be used in an indefinitely large number of ways.

I‘ve been noticing this flexibility while writing (still!) my book on narrative strategies in 1940s Hollywood. In particular, I was looking at fantasy tales and the peculiar problems they pose for filmmakers. First, how do we represent ghosts, angels, and other visitors from the Afterlife? And how do we make sure that audiences understand that what we see isn’t necessarily what some of the characters onscreen are seeing?

Angels unawares

Our Town (1940).

On the first problem: Today we have CGI resources that allow Afterlifers to move freely among the living characters. These effects were much harder to achieve back then. The supernatural-fantasy genre developed its own conventions (yep, schemas). Most films resorted to presenting the Afterlifer in double exposure.

But superimposed characters can’t move easily among the clutter of furniture in a set. A supered ghost can’t go behind a sofa; the sofa will always be visible through it. You might resort to a traveling matte shot, as William Cameron Menzies did in Our Town (1940), when Emily revisits her family after her death. The shot (just above) is particularly flashy because the younger Emily is also in it.

Or you could pull off the remarkable trick in Earthbound (1940). Here a ghostly Warner Baxter settles comfortably into the middle ground and strides around behind furniture and other actors.

He can even give up his seat to an old lady and shift to another.

These effects were achieved by a technical feat that I don’t fully understand. (See the codicil.) But the trick wasn’t widely adopted, and most filmmakers opted for a simple expedient. Typically the Afterlifer shows up as a superimposition, but he or she gradually materializes and becomes a solid presence like all the other actors. This is from The Canterville Ghost (1945).

Then comes the second problem. Sometimes the living can see the spectre, but sometimes not. In Here Comes Mr. Jordan, the angel Jordan and Joe the prizefighter arrive from the Beyond and watch the murderous couple from behind. They aren’t visible to the living, but they’re just as tangible.

If a living character seems oblivious to the otherworldly guest, we’re to assume that the guest is invisible. Each film has to inform us of who can see what, and most films do—redundantly. The spook or divine messenger will explain that the living can’t see them, or that only certain characters can. (Sometimes children and animals can see them while grownup humans can’t.)

These conventions can get tweaked. Once we know the Afterlifers aren’t visible to the living, they can comment on the action from the sidelines, as when the dead pilot in A Guy Named Joe (1944) slips in wisecracks while his girlfriend is wooed by a young aviator. In the comic The Man in the Trunk (1942), an all-too-tangible ghost can’t follow a character leaving a room. He explains, “I failed my examination on how to walk through walls.” In The Remarkable Andrew (1941), the ghosts of US founding fathers can ransack offices for evidence in an utterly unconstitutional search and seizure. Most ghosts can pick up objects, but the ones in The Cockeyed Miracle (1946) can’t, a fact redundantly explained to us. This generates suspense when they try to grab a fallen bank check. (Incidentally, this is a long, skillfully directed scene, and it does have recourse to a matte shot when one ghost tries. unsuccessfully, to hide the check by standing on it.)

All of these tweaks rely on continuity editing. But in the course of the 1940s, I’ve noticed, filmmakers played a little more ambitiously with the Afterlife conventions, and continuity style allowed them to do it. The results are sometimes provocative.

Ghosts coming and going

Consider the arrival/departure of the Afterlifer. The default is the special-effects twinkling that lets him or her materialize into the scene and fade out of it. But some filmmakers tried more natural options. In Alias Nick Beale, the title character, aka Satan, strolls in from offscreen, or, thanks to John Cromwell’s staging, is masked by other players before being revealed on the scene. He’s presented to all the characters as a real person, but the staging gives him arrivals of relaxed abruptness.

Joseph Mankiewicz’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) finds other ways to avoid the hugger-mugger of transparency and melting departures. Captain Gregg assures Mrs. Muir that to her he is “like a blasted lantern slide,” but for us he just steps into the frame and stays on as a solid presence. He disappears just as simply: Mrs. Muir turns away, then a new shot shows that Gregg has gone. Good old shot/reverse shot does the trick.

It’s neat that the second reverse shot on Mrs. Muir reaffirms Gregg’s absence by making her seem more isolated than the earlier mid-shot does. This cut-back to show her isolation after his departure is stressed even more in a later scene, when a medium shot shows her turned slightly away from him; in that interval, he disappears again.

Only after the captain has decided to leave her forever does he resort to the standard spook trick of dissolving away. But in this melancholy context, the familiar device takes on a forbidding finality. He leaves her sleeping and has magically made her forget all about their year together.

In the epilogue, when the elderly Mrs. Muir dies, the captain returns, sturdy as ever, and again the film avoids the cliché. The default schema is to let the dead person’s spirit float up in superimposition from the corpse. Instead, Mankiewicz presents Gregg standing over the lady in a tight shot and simply lifting the now eternally young Mrs. Muir into the frame. Again, all we need is shot/reverse shot, this time with the extra intimacy of an OTS.

These uncommon options take us a little by surprise, refreshing the genre conventions, while also suggesting that the films drive a little deeper into the heart than the usual spook story. The simplicity of presentation helps us take their spectral affair more seriously.

In The Bishop’s Wife (1947) the angel Dudley, like Gregg, comes and goes via offscreen space. A pan follows Henry the bishop, who hears a noise outside his study. The shot pays off with a reverse-angle cut to Dudley, now magically present at the fireplace where Henry was.

At other points, as in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, the framing excludes Dudley, and when we cut to the long shot Dudley is gone.

Soon, though, there’s a gag on the device. Henry, furious with Dudley, turns away and prays that Dudley will leave him. As earlier, the camera tracks in.

At first it seems that the prayer has been answered, when the camera tracks back from Henry and we see his slightly surprised expression, implying that Dudley has vanished.

But it’s then revealed to us, before Henry knows, that Dudley has changed position and is still in the room.

This quiet revision of the schema is in keeping with the film’s other jabs at Afterlifer conventions. At another point, Henry demands that Dudley execute a miracle. He locks the study door, evidently expecting Dudley to stalk through it in the usual phantom fashion. Instead, Dudley just twists the knob, magically opens it, and exits, closing it behind him and leaving Henry to bang against the relocked door.

Re-turning the screw

In general, supernatural romances play down the magical side of the Afterlifers’ visits. This is partly because they rely on a certain ambiguity about who can see what.

Henry James’ brilliant tale “The Turn of the Screw” provides an instance that people have argued about for generations. The unnamed governess, sent to take care of little Miles and Flora, starts to see dead people: the servant Peter Quint and the governess Miss Jessel. Most of her encounters with the ghosts take place when she’s alone, or with the children. Since the story is narrated from her viewpoint, and in the first person, we have no other testimony about the apparitions. The children seem to spot the spooks, but we can’t be sure. And we can’t be sure that they aren’t simply figments of the governess’s imagination. In the one scene that brings in another witness, the housekeeper Mrs. Grose declares that she can’t see Quint or Miss Jessup. Is the governess mad, or are the children really haunted by the corrupt couple?

The tension exemplifies what narrative theories Tzvetan Todorov called the “fantastic,” the tale of uncertain explanation. The fantastic hovers between scientific, or at least real-world explanations, and supernatural ones. Either the ghosts exist, as in most ghost stories, or they can be explained psychologically, as the narrator’s hallucinations.

Actually, in film, and I think in “The Turn of the Screw,” there’s a third possibility: that the Afterlifers exist as beings who can be seen only by the select few. In “The Turn of the Screw,” Flora definitely seems to see Miss Jessel on one occasion, so perhaps we can posit that the governess sees the ghosts when Mrs. Grose can’t.

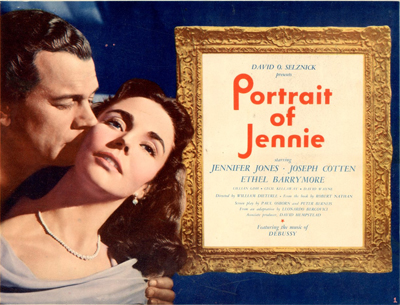

This possibility is of course the premise for The Sixth Sense, and we find it as well in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, in which Gregg is visible only to Mrs. M. The situation is more equivocal in Portrait of Jennie (1949). In this film, David O. Selznick inflated the fantasy-romance genre as he had pumped up the historical drama (Gone with the Wind), the home-front film (Since You Went Away), and the western (Duel in the Sun).

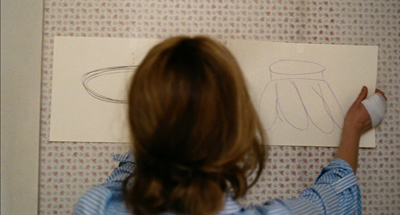

During the winter and spring of a single year, the luckless painter Eben Adams encounters Jennie at different points in her life: as a little girl, a teenager, a college student, and a mature woman. He falls in love with her. Their penultimate encounter takes place when she comes to his apartment and allows him to paint her portrait. Then she disappears.

Is Jennie a time traveler or a ghost or an illusion, or even a supernatural muse? A bit of each. After each brief visit she withdraws, leaving Eben yearning for her. The art dealer Miss Spinney suggests that in order to paint well, Eben must love someone, so perhaps he has conjured up Jennie to inspire his art. It’s true that he sketches, draws, and paints several Jennies. (The final version, the portrait, won’t be shown us until the film’s last image, in blazing Technicolor.) And it’s true that, in a scene much like that featuring Mrs. Grose in James’ tale, we get a hint that Eben is hallucinating Jennie.

He has just spoken with the adolescent Jennie in Central Park when Spinney comes up to him. He watches Jennie go off, in a standard passage of continuity editing.

But then, thanks again to continuity eyeline technique, Spinney doesn’t see her.

Normally this cutting pattern would suggest that Jennie is purely Eben’s vision. (For a modern example, see Johnnie To’s The Mad Detective.) Yet we will soon learn that Jennie did exist. Playing detective, Eben discovers that she was orphaned, taken care of in a convent, and left for college—all things her apparition told him. Worse, he learns how she died: on a rocky seacoast he has already depicted in some paintings.

Selznick was concerned to make Jennie neither a real person nor a pure product of Eben’s imagination. In an early story conference he remarked that Jennie is both in Eben’s mind and in some really existing realm. “We must convince the audience that this story may be strange and odd, but it’s true. All the other characters may say, “Poor Adams, he must be nuts,’ but we know it is true.” The fact that only Eben can see Jennie doesn’t make her a figment of his imagination. Eben may have conjured her up, but she also chose to visit him, predicting that some day he will paint her portrait. The man has, somehow, met a woman from a spiritual world who has been seeking him. Eurydice-like, she will be pulled back into it.

Too few fancies, one powerful friend

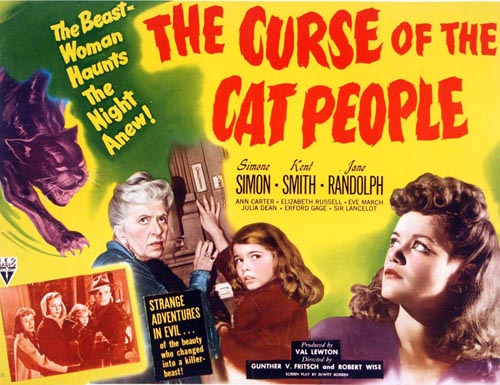

Recognizing that spirits can become selectively visible to the living helps explain the delicate power of another supernatural fantasy of the period. The Curse of the Cat People (1944) uses hyper-judicious framing and editing to create perhaps the most mysterious 1940s Afterlifer.

Irena, the woman who can change into a panther, has died in The Cat People (1943). Her widowed husband Oliver has married Alice, and their child Amy, dreamy and unpopular, wishes for a friend. Near the start of the film we’re led to think that Irena is that imaginary friend, wholly a product of Amy’s mind. Irena comes to her in the garb of a traditional princess or fairy godmother, a bit like the fairy of Pinocchio (1940), so we might take her as Amy’s imagining. And the teacher Miss Callahan, who might seem to be playing the raisonneur, says that the little girl has “too many fancies, too few friends.” But that doesn’t seem to me quite right. I don’t think that ultimately Irena is Amy’s projection. Nor are we exactly in the realm of Todorov’s fantastic, hesitating between subjective and objective explanations.

Consider the progression in the film’s depiction of Irena. At first, Amy is shown playing in the garden, purportedly with her friend but alone in the frame.

Later she says that her friend taught her a song, but she can’t recall the words. This suggests that that encounter, kept offscreen, is a vague one. That night, as Amy awakes from a nightmare, she is soothed back to sleep by her friend, whom we hear softly singing but see as only a shadow. Her lullaby continues as Amy sleeps.

Still later, Irena appears to Amy in the garden only after Amy sees a picture of her. Irena appears un-magically, entering the shot as casually as Dudley or Captain Gregg and holding the ball that Amy has tossed out of frame.

Amy asks her who she is. “I’m your friend.” The fact that Amy doesn’t recognize her from earlier friend-encounters, suggests that the friend wasn’t yet defined in bodily form. She had magical powers, such as darkening or lightening the garden or teaching Amy a song, but she assumed no particular shape. We, however, saw her female silhouette while Amy slept. Now Irena is fully embodied, and we can see her along with Amy.

Apart from the Irena scenes, we do get into Amy’s mind. But the techniques used in those scenes are ones that are never applied to Irena. When a deranged neighbor lady recites the tale of the Headless Horseman, we get exaggerated optical POV shots from Amy’s perspective and the subjective sound of wind and horses’ hooves.

The sounds are repeated as auditory flashbacks in Amy’s nightmare and while she is hiding in the forest during the climactic snowstorm. Later, Amy will calm the old woman’s homicidal daughter by envisioning her as Irena (in a superimposition) and embracing her as “My friend.”

From a storytelling standpoint, such images and sounds are sharply distinguished from Irena’s scenes with Amy. Those are treated in quite a neutral, objective manner.

There’s more. At the midpoint of the plot, in a crucial scene, Oliver learns that Amy considers the dead Irena as her playmate. He’s convinced she’s imagining it all. Anxious and angry, he takes her out into the garden and demands to know if Irena is there. Amy sees Irena under the tree, but Oliver doesn’t. As in Portrait of Jennie, reverse-angle cutting conveys each character’s vision.

In cinema, we assume objective (fictional) reality to be the default value. So the incompatible viewpoints of Amy and Oliver in the garden might suggest that Irena exists only in Amy’s mind. But in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir and Portrait of Jennie, the protagonist can see the ghost when no one else can. Nothing in this garden encounter denies the possibility that Irena is a ghost visible only to Amy and us.

We get some immediate backing for this. When Amy looks at Irena a second time, at Oliver’s insistence, Irena puts her finger to her lips, as if urging Amy not to acknowledge her.

This, to put it stiffly, is the action of an independent agent. Amy is unlikely to conjure up an imaginary friend who warns her to keep quiet. And by telling Oliver that of course she sees her friend, she disobeys just as briskly as if Irena were of flesh and blood.

We have a clincher at the very end of the scene. Oliver and Amy go in, turning away. Neither sees the garden, but we get two shots of Irena watching them and reacting unhappily.

Again, it’s hard to reconcile this image with Irena being a pure projection. She’s behaving like an ectoplasmic free agent. In addition, Alice and Oliver, despite their skepticism about Amy’s friend, don’t rule out supernatural goings-on completely. At various points both mention they sense Irena’s presence in the house. Irena has become in the course of the action a full-fledged ghost, but one with benefits.

The epilogue confirms Irena’s otherworldly mission. As Oliver takes Amy into the house, he asks if she can see Irena. She looks and sees her, smiling.

Can Oliver see Irena? Now that he’s decided to trust Amy, he says yes—without even looking.

As in the earlier garden scene, once father and daughter have gone inside, we’re treated to an independent shot of Irena under the tree. And now she melts away, in the conventional disappearing act of an Afterlifer. As with Captain Gregg’s withdrawal from Mrs. Muir, by saving this well-worn option for this moment the filmmakers invest it with an air of permanent departure.

The Curse of the Cat People cleverly invokes the possibility that Irena is purely imaginary, then dispels it. For once, nobody redundantly explains to us who can and who can’t see the ghost; we have to figure things out. Instead, the vague role of imaginary playmate gets gradually defined as Irena, the ghost. Continuity editing is recruited to suggest that Irena is coalescing into the friend Amy wishes for. At first only an atmosphere, then a shadow, and finally a properly solid spirit, Irena is a shape-shifter, more elusive than other apparitions of the period. The plot creates a sympathetic spirit seeking to console a lonely child and correct her father’s harsh, plodding common sense. Perhaps making amends for her effort to destroy Oliver’s romance with Alice in the previous film, the dead cat-woman fills out the role of imaginary playmate and saves a family.

There are other ingenious ways that the conventions of 1940s supernatural films are tweaked by the resources of continuity style, and I’ll be considering them in the book. The general point is that even schemas as commonplace as eyeline matching, or conventions as hoary as having a ghost dissolve out of the scene, can take on new force when filmmakers practice their craft with discreet intelligence.

Earthbound‘s ghost effect derives from a prism set in front of the camera. Warner Baxter is located in an adjacent set, and one face of the prism was silvered to reflect him onto the primary set. The best description I’ve found is here, thanks to good old Lantern. But we need more information. How can Baxter move so precisely around “our” set if he’s offscreen? Presumably, he’s in either a black set or one with furnishings laid out like ours. In that case, the furniture would need to be draped in black, so parts of his body will be blocked to the right extent. But in either case, we need to explain how he manages to synchronize his movements so exactly with the actors in front of the camera. If you know more, please correspond!

My quotation from Selznick comes from “Portrait of Jennie Conference notes (1/20/47),” David O. Selznick collection, Box 1123, file 11, Harry Ransom Research Center. Thanks to Emilio Banda and to Steve Wilson, Curator of Film at the Harry Ransom Center.

I’m using the concept of an artistic schema as E. H. Gombrich does in Art and Illusion (2000). For more about it on this site, see these entries.

You probably know that “The Turn of the Screw” was filmed as The Innocents (1961). It’s also the basis of a strong Benjamin Britten opera.

A vast survey of Afterlifers on screen is provided in James Robert Parish, Ghosts and Angels in Hollywood Films (McFarland, 1994).

For more on my still-in-progress book on 1940s Hollywood, go here and here. If you’re keen on the Forties generally, you might be interested in The Rhapsodes, my study of film criticism of the period, to be published in March by the University of Chicago Press.

Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101

Premium Rush (David Koepp, 2012).

DB here:

After nine years, over 700 entries, and many essays and other stuff, this contraption of a website has started to intimidate us.

If we’re intimidated, you might be flabbergasted. Although a set of categories sits on the right to guide your exploration of this tangled databank, those too loom large and discouraging. So we’ve decided to tidy up by–how else?–adding another entry.

We’ll occasionally offer a stripped-down guide to our writing on certain topics. We’ll steer you to entries that we think represent the core of our thinking on a problem, and then add some that probe more deeply, for those who want to go beyond the basics. Since one of our areas is narrative theory and analysis, a good first effort, we thought, would be to produce a sort of DIY syllabus that systematically surveys the topic as we’ve explored it. And since we’ve often written about classical Hollywood storytelling, and since many of our readers are interested in that…well, the syllabus sort of wrote itself.

We call these ideas open secrets of storytelling because by and large they aren’t acknowledged in the screenplay manuals that aspiring writers read. In most cases, we’ve had to devise our own concepts and terms, based on watching hundreds of movies. Yet these observations are wide open, available in our books and on this site.

Now comes our chance to pull them together. The result isn’t an utterly comprehensive theory of classical Hollywood narrative, but it does give a fair sampling of the range of questions we’ve tried to answer about it. The topics, linked to essays and blog entries, are arranged in three layers.

The most basic layer is an array of key ideas about story worlds, plot structures, and strategies of narration. These ideas are introduced in the first entry, “Understanding film narrative: The trailer.” Discussions of other basic concepts follow. Just reading the entries pegged to those topics, you could get a solid sense of what we’re aiming at. For most of those, we also propose a film you might view to test how the ideas work.

At a second level, for some topics we include some entries that dig deeper. They’re either more complex and advanced, or they provide some historical background.

Finally, after we’ve reviewed the key topics, we add a batch of case studies that use several of the tools we’ve laid out. These are usually very deep dives into particular films. They aim to show how the analytical ideas can bring out distinctive features of particular movies. The case studies are pretty wide-ranging, but they tend to hover around specific problems, such as adaptation or the creation of fantasy worlds.

How could you use this resource? A teacher in high school or college could draw on it as a partial syllabus or just a thumbnail list of supplementary material for a course. Teachers using Film Art: An Introduction could treat it as a supplement to our section of Chapter 3 on classical narrative. Or a student might find an idea for a paper in this vicinity.

Since we’ve always tried to link film studies and filmmaking, we hope that practitioners might be interested too. For example, an aspiring screenwriter could take this as a weekly reading/viewing agenda, treating it as a free course in story analysis. General readers who simply want to know more about the mechanics of cinematic storytelling should find something provocative here too. For everybody: Feel free to use it as Narrative Analysis 101.

We thank our many loyal readers of this blog, as well as the many more who have just dropped by once or twice. Your continued interest has helped us keep going.

Open Secrets of Hollywood Storytelling

The basics

Understanding film narrative: The trailer. Suggested viewing: The Wolf of Wall Street.

Advanced: Three Dimensions of Film Narrative: Narration, plot structure, and story worlds. Suggested viewings: The Godfather, Jezebel.

Advanced: Stories beget stories. Suggested viewing: American Hustle.

Actions and agents

Introduction to classical plot structure. Suggested viewing: Many possibilities listed.

Historical background: Is there a 3-act structure?

Action films: Did spectacle kill classical plotting? Suggested viewing: Mission: Impossible 3.

Advanced: Block construction. Suggested viewing: Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction.

How many protagonists? Suggested viewing: The Big Short.

The importance of coincidence. Suggested viewing: Serendipity.

Narrative parallels among characters and periods. Suggested viewing: Julie and Julia, Enchantment.

Advanced: Fine-grained parallels between scenes. Suggested viewing: The Prestige.

Time shifts: How flashbacks work. Suggested viewing: The Power and the Glory.

Advanced: Time shifts without flashbacks. Suggested viewing: Exodus.

Advanced: Nested flashbacks. Suggested viewing: Passage to Marseille, The Locket.

Historical background: Flashbacks and plot problems. Suggested viewing: The Great Moment, All about Eve.

Replays. Suggested viewing: Mildred Pierce.

Advanced: The auditory replay. Suggested viewing: Sudden Fear.

Network narratives. Suggested viewing: Grand Hotel.

Forking-path plotting. Suggested viewing: Source Code.

Advanced: Film Futures. Suggested viewing: Sliding Doors.

Historical background: What-if narratives. Suggested viewing: Dangerous Corner

Beginnings and endings: Molly Wanted More. Suggested viewing: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, The Silence of the Lambs.

Telling more or less

Visual storytelling. Suggested viewing: Mission: Impossible.

The hook between scenes. Suggested viewing: Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler; National Treasure.

Narration: omniscient versus restricted. Suggested viewing: Cloverfield.

Historical background: Hitchcock, suspense, and surprise.

Alignment and allegiance. Suggested viewing: House by the River.

Character subjectivity, optical and mental. Suggested viewing: The Silence of the Lambs.

Historical background: Subjectivity and sound. Suggested viewing: Nightmare Alley, The Fallen Sparrow.

Voice-over narration. Suggested viewing: All about Eve.

Advanced: Dead narrators. Suggested viewing: Laura, Confidence.

Historical background: Inner monologue. Suggested viewing: Strange Interlude.

Case studies in narrative analysis

These are exercises in film criticism that utilize several of the tools laid out above.

Boyhood and Harry Potter: The actors’ lives as part of the narrative.

Eastern Promises: Thematic echoes in an auteur’s narratives.

Gone Girl: Suspense and thriller conventions in fiction and film.

Gravity: Narrative innovation within mainstream cinema.

Inception: Goals and parallel construction; managing multiple plotlines.

Moonrise Kingdom: How to make a modern fairy tale (with some help from merchandising); furnishing alternative worlds.

Premium Rush: How goals and deadlines create tight construction.

Side Effects and Safe Haven: Fragmentary flashbacks and patterns of suspense.

Slumdog Millionaire: Adapting a novel to classical norms.

The Bourne Ultimatum: Plotting across franchise installments.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer: Classical structure in genre fiction.

The Hobbit: Adaptation and length; adaptation and change.

The Magnificent Ambersons: How to manipulate time without flashbacks.

The Prestige: Using sound to enrich flashback construction.

The Walk: Each act a different genre.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: Elliptical narration: The viewer’s responsibility.

As we write more entries relevant to narrative, we’ll revisit this DIY syllabus.

Needless to say, we consider these matters more closely in several of our books. See The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, by Kristin, Janet Staiger, and me, and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. For my part, there’s Narration in the Fiction Film and The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. I’m at work on a book on narrative innovations in 1940s Hollywood, the central source of much that we encounter in today’s films.

Pick your protagonist(s)

Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015).

DB here:

We’re used to sorting movies by periods, genres, and the individuals associated with them (stars and directors especially). But we can also distinguish films by their styles and narrative forms. So there’s not only a “film noir” style but other group styles, like the tableau approach seen in the silent cinema, or the deep-focus one of Hollywood in the 1940s-1950s. Similarly, we can think about types of storytelling strategies.

Someone might object that at least genre and other categories are in filmmakers’ minds, whereas it’s unlikely that any American in the 1940s set out to make a film noir as we understand it. (That term, and category, came from France, and somewhat after the fact.) Similarly, Ford probably didn’t think he was making a “classically constructed” Western in My Darling Clementine; he was just making a Western.

One reason we might construct these categories is to bring out the principles that filmmakers seem to follow intuitively. Perhaps no screenwriter ever thought explicitly about scene hooks, but the device is common enough to suggest that they believed the device was a useful tool.

Besides bringing out the regularities of filmmakers’ craft in certain times and places, constructing categories allows us to understand the creative choices they face. Maybe you handle a scene in a two-shot or in several reverse-angled singles. Both are permitted, each has certain advantages, and filmmakers spontaneously choose among these alternatives.

In effect, we’re reconstructing the menu of options available to filmmakers in certain times and places. If we do it carefully, we gain understanding of what each option can yield, and what certain filmmakers can achieve if they try something new.

Kristin and I have been in this game for decades, and our work on norms of film form and style has surfaced in our books, lectures, and blog entries. One set of analytical categories we’ve proposed is based on how movies use their protagonists. I was struck by how many films at end of 2015 and the start of 2016 illustrate a range of options currently available.

It turns out that these options are of long standing; they’re another example of how even recent movies owe a lot to the classical Hollywood tradition. That’s not to say, though, that they might not revise or tweak that tradition. Some filmmakers are innovative by temperament, and besides, there are career rewards when innovations come off. (Just ask the maker of Pulp Fiction.)

The categories depend on determining which character(s) can function as protagonist(s). That depends on the goals, the obstacles to the goals, and the relationship between the goal-striving character and other characters and story lines. Traditionally, in a two-hour Hollywood feature, a principal goal is articulated in the first half-hour or so. Kristin has argued that after this “Setup” portion comes others: a “Complicating Action” (also lasting about half an hour) that changes the goal and in effect creates a new setup; a “Development” which consists of delays, backstory, and fresh obstacles to the goal; a climax that resolves the issue; and an epilogue (screenwriters called it a “tag”) that confirms a certain stability in the situation. The major parts roughly divide the film into quarters, contrary to three-act accounts.

So today I look over the protagonist menu, based on some current offerings. Of course there are spoilers.

One, with benefits

Daddy’s Home.

Take as a baseline the movie organized around one protagonist. A clear example from this holiday season is Daddy’s Home. Stepdad Brad (Will Ferrell) has read all the touchy-feely parenting books and applies their lessons to raising the kids he has inherited by marrying Sara. But Dusty (Mark Wahlberg), Sara’s charming and macho ex, returns from his mysterious life in espionage and rapidly takes over the household. In an escalating series of mishaps, Brad proves unable to live up to the hip and edgy things that Dusty dreams up for the kids.

The climax comes when Brad, after showering Megan and Dylan with presents, gets drunk at a basketball game and humiliates them all with a public confession of inadequacy and a pair of unguided free throws. Eventually the battle of the two parenting styles—comforting versus edgy—is resolved when at a father/daughter dance Ward’s nonviolent, somewhat goofy, approach to conflict tamps down an explosive confrontation with a father spoiling for a fight.

The classic situation is established: our protagonist has an antagonist. Dusty is an infighter who seizes control of every situation. As you’d expect, Dusty is winning the race for the kids’ affection during most of the film; even Sara seems to be feeling some of her old attraction to him. As the antagonist, Dusty makes his intentions clear about two-thirds through the film: He will not give in. This precipitates Brad’s suicidally expensive efforts to shower his kids with presents. Deeply shamed, he moves out. Dusty seems to have won.

But Dusty has a weakness. He can’t manage the drab daily responsibilities of parenting—making the kids’ lunches, driving them to school—that Brad enjoys shouldering. At the climax, Dusty has gained respect for Brad and soon remarries, becoming the devoted father of a stepchild. In a traditional comic reversal, he must confront the kid’s birth father, who is a bigger thug than he ever was.

Daddy’s Home reinforces our alignment with the protagonist Ward through his voice-over narration, though at the end the integration of the two families is given by letting Dusty and Sara chime in too. The emphasis on Ward, his confrontations with Dusty and his kids, and the hilariously bad advice offered by Ward’s boss (a classic sidekick role) fulfill a common template for one kind of classical plotting. The protagonist comes to the plot with his goal already decided on, and he has to defend it against a tangible threat.

There’s another option: letting the protagonist discover the goal in the setup. And there’s the possibility of presenting not a single powerful antagonist like Dusty but several. These forces in various ways take on the task of blocking the protagonist’s goal.

Some critics have thought David O. Russell’s Joy somewhat messy, but I think that’s partly because the film spreads the antagonist function across many vivid secondary characters. In my view, as Bernie Sanders might say, the plot remains pretty classical.

The Setup establishes Joy’s life as a disaster. Her childhood dreams of creativity have been forgotten after years with her dysfunctional family and the demands of her children and job. Around the half-hour mark, Joy’s wounds from cleaning up a broken wine glass send her into a dream in which she rebukes herself for her passive life. She wakes up and starts designing a miraculous mop. If her initial goal was simply muddling through, her new goal revolves around transforming her life by creating and marketing this product. This new goal sets the key for the Complicating Action.

At the film’s midpoint, Joy convinces the producer overseeing the Quality Value Channel to add her mop to the offerings. The Development section consists of more obstacles and some triumphs, so that eventually sales take off. But her family butts into her business and plunges her into bankruptcy. This, her darkest moment, is overcome when she confronts her Texan partner and threatens to take him to court for the fraud she has discovered. She pays off her debts. In the epilogue, we see her as a successful businesswoman helping other struggling inventors.

This, of course, is just the film’s spine. In the course of this plot, Joy discovers she has reserves of courage, determination, and a sense of her own worth. Weaving through it all is the voice-over narration of her grandmother who not only fills in information for us (even from beyond the grave) but also serves as a prod for Joy to persist in her desire to make things of value. There’s also a clever opening showing a soap-opera performance in the manner of Straub/Huillet; it’s later replayed in normal TV terms.

Joy has allies—her ex-husband and a loyal friend—but she faces many antagonists, an array of family and predatory business people. Where Joy most alters the traditional plot layout, I think, is in its refusal to include a story line involving romance.

Most Hollywood plots are double-stranded: a line of action about romantic love, and another line, usually about work. Joy doesn’t revive her marriage and instead concentrates on her fulfillment of her dream. Having seen Silver Linings Playbook and American Hustle, we might expect Joy (played by Jennifer Lawrence) to hook up with the QVC producer played by Bradley Cooper, but it doesn’t happen. Still, Joy remains a nice example of the plot focused on one protagonist who struggles against a range of antagonists, each contributing particular obstacles. A comparable example from recent releases would be Bridge of Spies.

It takes two

Carol.

Alternatively, there’s the dual-protagonist plot. Two characters share a goal, or have complementary ones, and they work together. They may also come into conflict about it or about other matters. Often they’re a male/female romantic pair, as in the classic His Girl Friday, but they may also be male/male (The Other Guys) or female/female (The Heat). I’m told that Star Wars: The Force Awakens eventually settles into a dual-protagonist plot, but one example I’ve seen is Sisters.

At the start our protagonists are characterized as unhappy and incomplete. Maura (Amy Poehler), a divorcée, is oversolicitous and lonely; Kate (Tina Fey), a single mother, is irresponsible and frequently jobless. Neither sets out deliberately to improve her life, but they are put out on that path after learning that their parents have sold the family home. Screenplay manuals call this the “inciting incident.”

An encounter with the house’s snobbish purchasers convince the sisters to relive their wild high school days by inviting their old classmates to a wide-open party. They switch roles: Maura vows to become the wild girl she always hoped to be, and Kate agrees to become, for that night, the prudent one keeping an eye on things. At first the party is a boring affair, as their Gen-Xer friends have become staid parents, but at the midpoint, with the arrival of some serious drugs and a tattooed side of beef named Pazuzu, things explode.

The Development section is woven out of running gags, including a would-be party animal, a mean-girl rival crashing the event, a hunk attracted to Maura, and Kate’s efforts to keep in cellphone communication with her daughter Haley, who has nothing but disdain for her scatterbrained mom. The climax is precipitated when, having utterly trashed the house, Kate learns that actually she was to get the money from the sale. More seriously, Maura has secretly acted as a surrogate parent for the elusive Haley. The denouement presents a series of resolutions whereby the parents forgive their daughters, the house is rehabbed, and the sisters accept the need to sell the place and grow up. A tag shows the family united at—when else?—Christmas.

In Sisters, the intertwined lines of action yield goals around one the house-based line of action (preserving the house, trashing it, rehabbing it), but other goals emerge around love. Maura gets a boyfriend, Kate wins her daughter’s love, and both reconcile with their parents.

Sisters exemplifies how dual-protagonist films can show characters sharing a goal and still clashing with one another. Here, as in most such films, one of the pair may help the other, work against the other, or keep the other in the dark. Accordingly, so that we can appreciate all the schemes, misunderstandings, and screw-ups, dual-protagonist films tend to supply a wide range of knowledge. In Sisters, for instance, we know, as Maura and Haley and the parents do not, that Kate has lied about getting a new job.

By contrast, a single-protagonist film can restrict our knowledge to the hero or heroine, so that we share the suspense and surprise coming their way. Daddy’s Home restricts us almost completely to what Ward knows; Dusty is constantly surprising him with new subterfuges to win the kids’ love. Similarly, Joy is the center of consciousness in her film. True, we have the Grandmother’s voice-over supplying information, but it doesn’t really break with Joy’s range of knowledge. Grandma could have tipped us off early that about the Texan’s scam, but we learn of it only when Joy does.

In this way, plot structure interacts with what in literature is called point of view, or narration in the broad sense. Carol provides a striking example.

Patricia Highsmith’s original novel presents a single-protagonist plot. Therese, vaguely dissatisfied with the men in her down-at-heel bohemian milieu, falls abruptly in love with a wealthy wife and mother. Highsmith rigorously retains our attachment to Therese, so that we never know more than she does. She gets glimpses of Carol’s unhappy life with her husband Harge, her love for her daughter Riddy, and her struggle to obtain a divorce that will let her share custody of the girl. After Therese and Carol’s compromising road trip to Middle America, Carol returns to New York and the legal proceedings Harge is conducting. He has proof of Carol’s lesbian affair and intends to use it against her. But Therese learns of the progress of the case through letters and phone calls. Several chapters showing Therese simply waiting in Sioux Falls for news furnish some of the dread-filled suspense that Highsmith would generate in her crime novels.

The film displays the traditional four-part structure. The drive west is launched at the midpoint, just when Therese’s boyfriend Richard denounces her as infatuated with Carol. The couple’s trip, trailed by a detective tape-recording their lovemaking, serves as the Development. Interestingly, the book has a similar array of incidents, with the same plot point serving as the pivot to the second half. As I’ve argued before, popular fiction sometimes displays the same plot architecture we find in cinema.

But just following the four-part template doesn’t mean that the film and the novel are congruent. Carol shows how choices about narration can reshape plot structure. Apart from some changes in the original situation (e.g., Therese is now an amateur photographer rather than a set designer for stage productions), screenwriters Phyllis Nagy and Todd Haynes have made a crucial decision. They have expanding our access to Carol’s story line.