Archive for 2016

TONI ERDMANN, GRADUATION: Mediums, well-done

Graduation (Cristian Mungiu, 2016).

DB here:

More from this year’s Vancouver Film Fest, abundant as ever (over 200 features, over 300 films in all).

Comedy, Chaplin supposedly said, is life in long-shot, while tragedy is life in close-up. This is questionable on its face, but put that aside. What about medium shots? Maybe they’re either comic or tragic? Or maybe just neutral? Any shot framing the body from, say, the waist up to the head is the workhorse of most film traditions, and it’s ready to be recruited for almost any purpose.

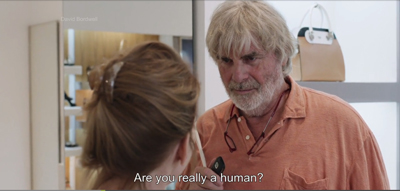

I was led to think about this handy tool when watching two strong and enjoyable films, Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation and Maren Ade’s Tony Erdmann. Both directors made some similar artistic choices, such as that slightly swaying handheld framing that seems de rigueur in many films nowadays–the “free camera,” as the Danes call it. But the two films show different ways of exploiting the medium-shot of people talking. The differences, I think, depend on both genre factors and one crucially diverging choice.

Screwball comedy with a German accent

Toni Erdmann updates screwball comedy: a mischievous madcap disrupts the staid life of an uptight character s/he loves. In classic Hollywood the madcap might be a wild woman (Bringing Up Baby) or a free-spirited man (Holiday), with romantic union the result. The variation here is that the madcap is a father. Winfried tries through pranks and impersonation to loosen up his rigid daughter Ines, who’s striving to be a cool corporate barracuda.

The plot is a series of encounters in Ines’ high-stress professional life. Her rounds of meetings and cocktail parties are constantly invaded by the bulky Winfried. Sometimes he’s his unkempt self (often adorned with splayed monster teeth), sometimes he’s a fake businessman/diplomat named Toni Erdmann. When father shows up, she’s mortified. She resorts to the classic strategies of the screwball target: flight, pretending not to know him, and desperately going along with the masquerade in hope that it will pass. Finally Winfried breaks down her defenses, and we get the obligatory scenes when the by-the-book character finally lets loose (here, through a heartfelt song and later by a creative effort at party hostessing).

The premise of screwball is a bit of a Jonsonian power trip. We’re asked to sympathize with people who have enough leisure and money to punk everyone around them. The cruelty of the put-on, with trusting characters gulled by free spirits, is built into the genre. In Toni Erdmann we have to be ready to accept not only the deflation of a CEO, which is always fun, but also the terrorization of working stiffs like delivery men and mechanics. To the film’s credit, there is a moment when Winfried learns the price that others must pay for a retiree’s cute mischief. Along the way is some sharp satire on corporate predation and its fashions in “coaching” and “team-building.”

All this is played out in good old medium shots. And those in turn are embedded in good old shot/ reverse-shot.

Toni Erdmann relies on shot/reverse-shot technique primarily, I think, because of the need to show reaction shots. A good part of comedy is reaction, and camera ubiquity allows us to watch the gag and the payoff in a tick-tock editing rhythm. Ade can time people’s responses to Winfried’s sinister leer in ways that maximize the laugh.

Shot/ reverse-shot has of course long been a mainstay of classical Hollywood continuity style, partly because it mimics the flow of turn-taking in conversation. Like side-participants in a real-life situation, we shift our attention from speaker to speaker, thanks to the cuts.

Over-the-shoulder framings help anchor us in the space of the scene, so we always know where we are.

Assisting that sense of stability is the so-called 180-degree system of staging, shooting, and cutting. This keeps all the eyelines, postures, and backgrounds fairly consistent. At several points, though, Ade’s reverse angles “break the line,” shifting us across the axis of action. This creates what’s been called “200-degree-plus” staging and shooting.

Fortunately, our pragmatic sense of who’s talking to (or looking at) whom overrides the slight jump. The shift can be smoothed if there’s a strong cue–as here, when Winfried turns his head from the courier on his doorstep.

When you have several characters present, and you’re willing to break the 180-degree line in your reverse shots, you can cheat positions from shot to shot in remarkable ways. A cut can magically delete a character for the sake of emphasizing another one’s reaction.

For example, at a fancy party, Winfried-as-Toni approaches a woman and claims he works at the German embassy. The first shot favors the woman, her friend, and a nervous Ines, who tries to pull Toni away.

But when we cut to a reverse of Toni, Ines is no longer beside the blonde woman.

She has been shifted to the left–in fact, moved completely offscreen–in order to supply a clear view of Toni. His sharp glance to the left confirms her position.

Cheating shot/ reverse-shot positions is a common tactic of classic continuity filmmaking, and Ade uses it freely. The more characters who crowd in, the more chance to cheat them. In some shots during the big party, Ines is close beside her boyfriend as her boss greets Toni. But in the 180-degree reverse angles the couple gets spread out, with the man pushed offscreen entirely, before a new setup brings them back–and deletes the boss.

It’s remarkable how little we notice these shot-to-shot disparities as long as positions are grossly consistent, and as long as we’re given other things to pay attention to. (Dan Levin has studied filmic “change blindness” experimentally.)

Throughout, Ade’s cutting and camera placement help us enjoy, moment by moment, the shocked, bewildered, and bemused responses to Winfried/Toni’s campaign to humanize Ines.

The case of the missing reverse shot

Change the genre from comedy to drama, though, and minimize editing, and you get something else. You get, for instance, Graduation (Bacalaureat).

Mungiu traces a few tense days in the life of Romeo, a provincial doctor living in a bleak housing flat. His daughter is promised a scholarship if she does brilliant exams, but before she can take the first test she’s assaulted and the trauma threatens to wreck her performance. To protect her, Romeo uses his network of friends to arrange for favorable grades. The scheme precipitates crises with the daughter, her boyfriend, Romeo’s wife, his mistress, and a mysterious attacker.

The film is essentially a set of two-handed dialogues, tracing how the pressure on Romeo builds from day to day and hour to hour. These encounters are filmed mostly in medium shots, as in Toni Erdmann, but with one essential difference. The shots are long takes, and they’re kept fairly stationary—that is, no circling or panning of the camera. Handling some scenes in just a single shot, Mungiu often avoids the shot/reverse-shot cutting we see in Ade’s film.

This choice might seem akin to the virtuoso long takes of Iñárritu in Birdman. But as I tried to show back when, Iñárritu’s long takes actually mimic the patterns and effects of shot/reverse-shot editing. In Birdman, we’re denied nothing because the moving camera always picks up the reaction that would normally be captured in a reverse-angle cut. By contrast, Mungiu doesn’t give us the long-take equivalent of continuity editing; he denies us reaction shots quite stringently.

In The Graduation, characters tend to interact in in lengthy profiled two-shots, not 3/4 reverse angles.

This framing gives us some access to the characters’ emotions. It’s worth mentioning, though, that profile shots aren’t strongly informative about a person’s facial expression. A frown or a smile is more “readable” in the 3/4 framing favored by reverse-angle cuts.

More remarkable, though, are those passages in which Mungiu simply denies us access to Romeo’s facial expressions by pivoting him away from us and denying a reverse shot.

Actors have turned their backs to the audience for a long time in both theatre and film, usually to enhance a gesture, to call attention to another actor, or to delay the revelation of the face. But since the reverse-angle cut is such an ingrained convention, we count on camera ubiquity; we expect to see everything. When characters have their backs to the camera, and the director doesn’t cut to an angle that reveals their reactions, this choice can have powerful narrative effects. It can make the character’s psychology more opaque and mysterious. It can also build suspense as we wait for some clues (in words or gestures) to the character’s response.

The withheld reverse angle, within longish takes, was a prominent tactic in Antonioni’s 1960s style, as in L’Avventura.

Mungiu isn’t quite so flagrant, favoring 3/4 rear view like the over-the-shoulder view of orthodox shot/reverse shots. This will do duty for orthodox POV cutting: We see what Romeo sees but not exactly through his eyes.

The result is to attach us to the protagonist but not in a deeply subjective way, as Hitchcock might with intense optical POV shots. These shots might suggest a perceptual subjectivity–we see what Romeo sees, more or less–we don’t know how he’s reacting. Sometimes, as when he and a colleague inspect an X-ray, we get almost no sense of the reaction, or what they’re reacting to.

In addition, Romeo is a fairly phlegmatic man anyhow; he’s hard to read even facing front.

His failed ambitions and troubled relation to his wife, as well as the mess he’s making of the exam scheme, seem to have given him a fixed, furrowed anxiety. I doubt that even Toni Erdmann could make him smile.

Still, most directors would probably have filmed Romeo driving his daughter to school, from an angle in front of the car, shooting through the windshield. And most directors would have revealed something of his response when, as his scheme unravels, the school principal orders him not to contact him again or come near his house.

Even more striking, at a climactic moment, he’s questioned by two policemen. I don’t have an illustration for you, but we’re perched over his shoulder and watch the two cops–not unsympathetic–explain to him at length the punishment likely headed toward him. We get no chance to see whether his facade cracks even a little. But observing him so often as a solid lump in the foreground or on the edge of the shot gives him, I think, a sort of obdurate resistance that suggests he will resist what’s coming. In these grim circumstances, stubborn stolidity gains a heroic quality.

Other characters, notably his wife and daughter, get framed in ways that allow us to track their emotions. It seems somewhat ironic that the sunniest, most straightforward and untroubled faces we see are those of the class lined up for the graduation picture.

No surprises here. The head-and-shoulders shot gets a lot of its impact from its coordination with other stylistic choices: the decision to cut (or not to cut), the selection of the angle (frontal, or from behind), and the overall tone of the film (grim or light-hearted). There are no general rules. Contra Chaplin, the close-up can be comic, as in Harold Lloyd. The long-shot can be tragic, as in Hou Hsiao-hsien or Edward Yang or Theo Angelopoulos. As with these shot scales, the workhorse medium shot is coordinated with other techniques to achieve its results in different contexts.

Thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Entertainment for their generous help in preparing this entry. Toni Erdmann is scheduled for U. S. release by Sony for 25 December. Graduation is distributed by IFC in the Sundance Selects collection; no U. S. release date yet announced.

I discuss the blend of cinematic convention and social intelligence elicited by shot/reverse-shot techniques in the essay “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” in Poetics of Cinema, 57-82. On the quick information pickup involved in certain facial views, see Vicki Bruce, Tim Valentine, and Alan Baddeley, “The Basis of the 3/4 View Advantage in Face Recognition,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 109–10; and Robert H. Logie, Alan D. Baddeley, and Muriel M. Woodhead, “Face Recognition, Pose, and Ecological Validity,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 53–69.

On the 200-degree-plus style in modern film and television, see The Way Hollywood Tells It, 177-179. On change blindness, an earlier blog entry is here. Another entry bearing on the matter, also VIFF-inspired, is “Where did the two-shot go? Here.”

The laconic rear-view shot became a common tactic of modernist cinema. For other examples, you can see this entry on Béla Tarr. But Mizoguchi got there quite a bit earlier.

Toni Erdmann (Maren Ade, 2016).

A decade at the Vancouver International Film Festival

The Red Turtle (2016).

Kristin here:

Recently this blog passed its tenth anniversary. Our first modest entry, on Christine Vachon’s book A Killer Life, was posted on September 26, 2006. The second was “A film festival for all seasons,” the first of David’s five reports on that year’s Vancouver International Film Festival, where he was a judge in the Dragons and Tigers competition for young Asian directors. Since then we both have come to VIFF nearly every year. Its organizers and staff are always welcoming and we can see lots of films in a relatively relaxed atmosphere free from the red carpets, the markets, and the celebrities that make some of the bigger festivals difficult to navigate. We’re delighted to be back in Vancouver now, reporting on its rich array of offerings for a tenth time.

The Rehearsal

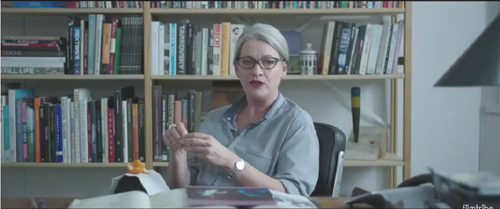

Canadian-born, New Zealand-bred, New York-dwelling director Alison Maclean gives us The Rehearsal (2016), her first feature since her best-known film, Jesus’ Son (1998). In between she has been primarily working in television, including episodes of Sex and the City and The Tudors.

The film begins with an image of an Asian woman in a blonde wig and ultra-high-heel shoes facing directly into the camera and miming a tennis game (see bottom). Such an arresting opening is a wise move, since the film’s early portions are mostly expository. The opening introduces Stanley, a young Maori man who gains acceptance to a high-pressure, prestigious drama school, despite his apparent lack of the necessary talent and drive. Overcoming his initial listlessness, Stanley gradually bonds with his classmates. He also blossoms somewhat under the tough-love approach, sometimes verging on cruelty, that is the policy of Hannah, the demanding head of the school (Kerry Fox, above, best known for playing Janet Frame in An Angel at My Table).

The opening image turns out to be a flashforward to a rehearsal of an original playlet that Stanley and a group of teammates must put on at the end of the school year. For their story they seize upon a current local scandal in which a tennis coach has had an affair with an underage pupil. Stanley has begun dating the girl’s sister Isolde, which gives him knowledge about the situation that the group incorporate into their play. The main suspense arises from Stanley’s failure to tell Isolde what his team is up to, despite the fact that inevitably she will find out. More drama arises from the effects of Hannah’s harsh methods on the students, particularly Stanley’s vulnerable roommate.

The Rehearsal currently has no American distributor but will play on October 5 at the New York Film Festival.

The Confessions (Le Confessioni)

Early in The Confessions a spectacular drone shot follows a moving car from above the treetops. Eventually the car arrives at a driveway crowded with news photographers, and the camera leaves it to reveal a huge modern hotel and then move beyond it over ta body of water. Though not as flashy, the rest of the film has the sort of lush cinematography (above) and rich musical score that are familiar from such other recent prestigious Italian productions as The Great Beauty.

The plot involves a sort of bitter parody of a G8 meeting, with eight representatives of major countries meeting under the guidance of the head of the International Monetary Fund. They are preparing to execute some sinister plan, under the guise of “creative destruction,” that will solve a current international financial crisis in a way that will benefit rich countries at the expense of the poorest ones. Daniel Roché, the head of the IMF, has also invited an Italian monk, Roberto Salus (played by Tony Servillo, so memorable in The Great Beauty and especially Il Divo), to attend.

The reason for Salus’ presence is not clear, though Roché requests him to hear his first confession in twenty years. Roché is soon found dead. It’s apparently a suicide, but some of the finance ministers attending the meeting seemingly try to eliminate Salus by casting him under suspicion of murder. The film turns into a cat-and-mouse game, with each seeking out Salus for devious conversations, punctuated with tantalizing flashbacks that gradually reveal what Roché had revealed during the confession scene.

Although on the surface the film seems to be developing into a thriller, it is too playful to be taken entirely seriously, and the wise, reserved Salus always delivers the final sardonic comic topper in his exchanges with each of the villains. There is even a suggestion of a sort of magical realism at a few points. Ultimately The Confessions is a somewhat uneasy mixture of genres but a highly entertaining one.

The Red Turtle

In the early days of the blog (December 10, 2006), I wrote an entry claiming that in contemporary cinema, animated films are on average more likely to be stylistically superior to live-action ones. Animated films have to be intensively pre-planned, including recording soundtracks in advance. Such careful preparation, which eliminates the easy reliance on “coverage” and limits changes in post-production, imparts a rigor and care that are too often missing in live-action features. Two experiences with animated films here at Vancouver reinforce my point.

David and I agree that The Red Turtle is a standout among the films we’ve seen so far. It’s an animated feature by Michael Dudok de Wit, the Dutch animator who won the animated-short-film Oscar in 2000 for Father and Daughter. The Red Turtle won a Special Jury Prize at Cannes this year. It also has Studio Ghibli’s name attached, which might lead to some raised eyebrows.

Studio Ghibli’s three legendary animators all retired in recent years: Hayao Miyazaki, after The Wind Rises (2013); Isao Takahata, after The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013); and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, after When Marnie Was There (2014). Rumors that the studio would shut down fortunately proved false, despite the fact that its crew of animators was disbanded. The Red Turtle is the first film to bear the Studio Ghibli name since Marnie. The studio, not Dudok de Wit, initiated the project, and perhaps it will henceforth support occasional hand-picked productions like this one.

Though The Red Turtle uses traditional cell animation, it does not particularly imitate the studio’s familiar style Nevertheless, the film is far from being a radical departure from its previous output. For one thing, The Red Turtle is vitally concerned with the depiction of nature. It opens with a storm that drives a single survivor from a shipwreck onto the beach of a small island, uninhabited by humans. His first contact with living things there comes when a curious sand-crab crawls up his pant-leg, and a group of these crabs provides touches of comic relief throughout.

Three times the unnamed man tries to escape aboard bamboo rafts (above), but each time a large red sea turtle destroys his craft (see top) and forces him back to the island. In the story’s first fantastical event, the turtle transforms into a woman, and the two soon fall in love, Adam and Eve in a sparse Garden of Eden. They gain a son, a tsunami introduces a note of threat into the idyllic depiction of nature, and ultimately they face mortality. The simplicity and fantastical elements of the story would be perfectly convincing as a rendition of an existing myth, but the story is completely Dudok de Wit’s invention.

The three human figures are drawn very simply and look like they were rotoscoped, though I can find no confirmation of that online. The depiction of the natural landscape and the creatures that inhabit it are, however, stunningly beautiful. Without attempting a photorealistic look, Dudok de Wit’s team have captured the look and movement of sunlit seawater, the rhythmic rustling of leaves, and even the differences in color between the exposed and the submerged surfaces of woolsack blocks of granite at the ocean’s edge. It is almost as if they have managed to rotoscope all of nature.

The classic films by the main directors at Studio Ghibli are more elaborate and complex than The Red Turtle, but the new film suggests that the studio will maintain its high standards in its future productions.

The Red Turtle was bought by Sony Pictures Classics and is scheduled for a mid-December American release.

Window Horses (The Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming)

While The Red Turtle is a high-profile animated film, Window Horses originated as an Indiegogo project. Its success in that campaign led Sandra Oh to back the film, signing signed on as a producer and providing the voice of the film’s heroine. The project gained additional support, including by the National Film Board of Canada. Still, it is likely to remain largely a festival item (it premiered at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival), with only a limited theatrical release in Canada early next year. (Information on that release is not yet available online, but news will presumably be posted on the film’s website.) It exhibits a lively imagination and stylistic sophistication that deserve a wider audience, which with luck it will achieve via streaming.

The story centers on Rosie Ming. With her Chinese mother dead and her father having apparently abandoned his family to return to Iran, she lives in Vancouver with her maternal grandparents. A self-published book of her verses leads to an invitation to a poetry festival in Shiraz. Donning a full chador in the hopes of fitting in, she finds herself surrounded by women wearing simple scarves and vibrant clothing.

The animation itself is colorful, with stylized faces that are vaguely reminiscent of Picasso (as in the tour-bus scene, above). Rosie stands out in her utter simplicity, rendered as a black-clothed stick figure with a round, white face sketched in only by eyes and, when she speaks, a mouth. Recitations of poems are accompanied by scenes of animation is a variety of styles, contributed by such animators as Kevin Langdale, Janet Perlman, Bahram Javaheri, and Jody Kramer.

Overall, it is an engaging and entertaining film, showing how much an independent filmmaker can do with limited means. In that it reminds me of Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues.

Films that have particularly impressed us so far include Pablo Larrain’s Neruda (playing again on October 9), Cristian Mungui’s Graduation (playing again October 5 and 11), and above all Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion (playing again on October 9). We’ll be blogging about these and others over the next several days.

The Rehearsal (2016).

Replay it again, Clint: Sully and the simulations

Sully (2016).

What happens in the Forties doesn’t stay in the Forties. That’s one motto of the book I’ve just finished on Hollywood storytelling in the period 1939-1952. The argument is that several narrative conventions that crystallized in that era became part of the Hollywood tradition and continue to shape the films of today.

I say “crystallized,” not “suddenly appeared,” because in general terms every significant technique I pick out has precedents in earlier years of American filmmaking. Forties filmmakers didn’t invent flashbacks, voice-over narration, dream sequences, and the like. What Forties writers and directors did was consolidate those techniques into major norms. They went on to explore, sometimes with startling delicacy, the techniques’ range and power.

This pattern of scattered invention, followed by consolidation and refinement, isn’t uncommon in the history of technology. The computer mouse was devised by several companies and individuals, but it became ubiquitous in the 1980s thanks to Microsoft and Apple. What historians call the diffusion phase of change created a foundation for future development.

The same sort of diffusion sometimes takes place in cinematic form and style. For example, flashbacks in the 1930s were fairly rare and, except for The Power and the Glory (1933) and a few other films, fairly perfunctory. They simply filled in information that had been suppressed earlier, usually providing the solution of a mystery. During the 1940s, when flashbacks became more widely used, filmmakers were obliged by the pressures of competition to explore the technique’s finer-grained possibilities, as in Kitty Foyle (1940), Citizen Kane (1941), Lydia (1941), and many other films.

Once a technique becomes common, and refined in its usage, later filmmakers can treat it as a taken-for-granted option. It seems likely that the development of flashbacks in the 1940s, in both American and other cinemas, laid the groundwork for efforts like Hiroshima mon amour (1959). American filmmakers reworked flashbacks in creative ways in Petulia (1968), They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), and other films influenced not only by 1940s Hollywood but also by 1950s and 1960s European cinema.

Call me biased, but now nearly every mainstream movie I see seems indebted to storytelling strategies consolidated in the 1940s. Take Sully. In less than ninety minutes, it runs through a wide range of narrative techniques. The fact that we take them so completely for granted, and understand them so swiftly, indicates the stability of what we call a Hollywood movie. It’s kind of miraculous that filmmakers continue to find ingenious ways to fulfill norms that were locked into place seventy years ago.

Clint the classicist

American Sniper (2014).

Before I get to Sully, let’s pause on other recent films directed by Clint Eastwood. (Yes, spoilers will be involved.) They illustrate just how fully narrative techniques associated with the 1990s-2000s have become mainstream resources. Although those techniques are largely revisions of possibilities crystallized in the 1940s, most people know them in their modern guise. Today’s audiences are more familiar with the intricately out-of-order flashbacks of The Prestige (2006) than those found in The Killers (1946) or Backfire (1950).

Hereafter (2010), written by Peter Morgan, lays out three story lines. A French TV journalist, after nearly drowning during a tsunami, is convinced she has had a vision of the afterlife. A London boy yearns to contact his dead twin. An American construction worker, as a result of perilous childhood surgery, has acquired the gift—or, as he says, the curse—of being able to communicate with the dead. Each protagonist’s experiences are treated as separate blocks, crosscut ever more swiftly, until the three converge at a London book fair. The American helps the boy contact his brother, and by meeting the journalist, who has written a book about her research into the hereafter, begins to feel he can rejoin the world.

Hereafter is what I’ve called a network narrative: a plot centered on several more or less equally weighted characters with independent goals. Their fates intertwine by chance (or fate). In the 1930s and 1940s, network plotting tended to be confined to a locale or vehicle, typically in a Grand Hotel situation. More dispersed and numerous story lines emerged with Altman’s Nashville (1975), though even that has a circumscribed time limit. During the 1990s and 2000s, both spatially confined versions and more free-ranging ones became quite common in filmmaking across the world. Hereafter revives the strategy, tying the parallel plotlines to a conception of a realm after death.

Hereafter’s second primary expressive option involves flash-cut visions of the afterlife—blurry, distorted images that give only a glimpse of what Marie the journalist and George the medium “see.” These aren’t sustained, so that, for instance, when George relays to someone what the departed is saying, the film stays objective, simply presenting George’s report on what he’s being told.

This reticence about showing us the Beyond allows us to reflect that at one crucial moment, perhaps George is improvising the advice that he claims to be passing along to the dead boy’s twin.

In a final twist, George’s curse changes to something more like a gift. When he manages to arrange a rendezvous with Marie, his vision of the afterlife is replaced by precognition in this world. Now his vision, clear and sustained, shows him kissing her. Or maybe he’s gained access to normal wish fulfillment.

In either case, the Hollywood clinch gets re-motivated.

Jersey Boys (2014) presents the rise of the Four Seasons, with emphasis on the lead singer, high-pitched and high-strung Frankie Valli. Although the bulk of the film takes place in the 1950s and 1960s, it climaxes with the group’s reunion at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990.

A common option would be to start at the reunion and then flash back to trace the group’s rise. Instead, the film roughly follows the layout of Marshall Brickman’s and Rick Elice’s book for the Broadway show. That presents the ups and downs of the group’s career chronologically, with each member narrating a block of scenes. In the stage version each block is labeled, cutely enough, with a season, from ebullient spring to doleful winter, with an extra-seasonal epilogue at the Hall of Fame.

The film version, also scripted by Brickman and Elice, doesn’t flag the seasons but does incorporate round-robin narrators. In the film’s opening Tony DeVito introduces us to the neighborhood and the formation of the group.

Later, singer-composer Bob Gaudio (above) and bass guitarist Nick Massi comment on stretches of the group’s rise and fall. They feel free to criticize each other, as when Nick says the trouble began well before Bob thought. These narrating moments are handled through to-camera address: each Season looks straight at us, explaining what’s happening, or just happened, or is about to happen.

Again, to-camera address can be found throughout film history, but the Forties made it salient by letting it bracket the entire film, often as the present-time frame for a flashback (Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, 1948; Edward, My Son, 1949; Young Man with a Horn, 1950; below). It’s rarer to have the narrator interrupt an ongoing scene, turn toward us, and break the fourth wall, but we do find it in My Life with Caroline (1941, below).

The Caroline device was revived in other films, notably Alfie (1966) and much more recently The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). The tweak that Jersey Boys introduces is the fact that the narrator uses the past tense to describe the scene he’s in–an occasional option in The Big Short (2015) too.

The tag-team narration in Jersey Boys doesn’t create sharply distinct blocks, in the Rashomon manner. Each singer’s segment roams pretty freely among other characters’ doings, so there’s no strong attachment to a single viewpoint. But some variations crop up. Frankie is the most minimal narrator. He never turns to the camera to address us, and we hear his voice-over comments only once in “his” stretch of the film. Perhaps that’s because he’s the character whose personal life is most crucial to the plot, and we see everything he’s up to. (Hollywood group protagonists often adopt a “first among equals” principle.) And at the final reunion, each of the quartet turns from the microphone to address us in quick succession, summing up their view of what’s happened. In Jersey Boys, as in Hereafter, some long-standing conventions are given moderately original handling.

American Sniper (2014) is the most linear and traditional of this batch, except for one tactic that becomes more important in Sully. The opening sequence shows sniper Chris Kyle perched atop a building scanning the Falluja neighborhood for enemy action. He sees a woman and child walking toward the Marine convoy, and she passes the boy what becomes visible as a grenade.

Chris must decide whether to fire. We then flash back to Chris as a boy shooting a deer and being told by his dad: “You got a gift.” There follow scenes tracing his childhood and young manhood, and his response to militant bombings of U. S. embassies: joining the Navy SEALS. At his wedding, he’s called to the invasion of Iraq.

This flashback, which consumes most of the film’s first “act” (ending about 25 minutes in), is followed by a return to the moment of decision on the rooftop. To prolong the suspense, the film replays Chris’s spotting of the woman and child with the grenade. He fires and kills both.

This tactic, of coming out of a flashback with a repetition of what initiated it, is yet another storytelling choice we find emerging in the Forties. One clear example is the framing of the long central flashback of Body and Soul (1947). The opening scene shows an eerily empty training camp before boxer Charley Davis wakes up from a bad dream and cries, “Ben!”

A fairly lengthy setup in the present follows before we get a long flashback tracing Charley’s career. At the conclusion of the flashback, again we see the shot of the camp, and again we see Charley awakening. A match-on-action cut takes us from that to the point where the frame story stopped: him lying on the table in his dressing room, just before the big bout.

The return to the camp has buckled the flashback shut in a way similar to the return to the Falluja roof in American Sniper.

The device of the reiterated flashback is developed more unusually in Eastwood’s J. Edgar (2011). The film follows a classic norm for the biopic: In old age, the central character recalls his or her life. Those flashbacks could be motivated as private memory, or as episodes recounted to someone. And in the Forties, that someone was often a reporter or transcriber, as in Edison the Man (1940) and The Great Man’s Lady (1942). If you count Citizen Kane (1941) as a fictional biography, then Thompson fulfills the role of listener.

In J. Edgar, the self-important Hoover has assigned FBI agents to take down his memoirs. Flashbacks inevitably follow. As the film goes on, the narration wedges in “unofficial” flashbacks, mostly scenes with Hoover’s life partner Clyde Tolson, and these are justified as purely private musings.

What’s interesting is that some material Hoover dictates proves unreliable. At the climax Tolson, who has read the manuscript, denounces it as a tissue of lies. We then get repetitions of key scenes from the dictation, all of which show that Hoover wasn’t involved in cracking the big cases he took credit for. The film decisively debunks Hoover’s myth that he was not only a superb administrator but also a heroic, hands-on field commander.

The lying flashback is yet one more minor convention of 1940s cinema. For those who haven’t seen the most important example, I’ll refrain from mentioning the title, but let Thru Different Eyes (1942) and Crossfire (1947) stand as examples. (At one phase of production, Laura, 1944, was planned to have a lying flashback too.) The replay emerges as a way to correct the first impressions.

In tracing precedents for these storytelling choices, I don’t mean to criticize them as unoriginal. The screenwriters of Jersey Boys and Hereafter, along with Jason Hall (American Sniper) and Dustin Lance Black (J. Edgar), are drawing upon models that have been circulating in Hollywood filmmaking for decades, and that became particularly salient in the 1990s and 2000s. These scripts are also revising the techniques in ways that seem to me original to some degree.

As for Eastwood, he’s said to “shoot the script,” so perhaps these more or less up-to-date narrative techniques are brought into his work through the screenwriters. But he’s also often called one of the last “classical” directors. Partly, I think, that’s a reference to his style: his fondness for establishing shots of buildings, shots of people arriving in cars or driving away, shot/reverse-shot dialogue exchanges, and unobtrusive Steadicam. In Jersey Boys, the musical numbers seem rather haphazardly put together, but Eastwood is cogent in developing action sequences, as the firefights in American Sniper show.

It’s not just a matter of style, though. To some extent the narrative strategies I’ve mentioned here have become part of today’s “classical Hollywood filmmaking.” Flashbacks, block construction, replays, to-camera address, network narratives, and bursts of subjectivity are so ingrained in contemporary filmmaking that we might want to think of Hollywood storytelling as a constantly expanding menu that discovers new flavors in traditional ingredients. The basic premises of classical narrative permit an indefinitely large range of variation, both large-scale and fine-grained.

Not a crash, a water landing

Most flashbacks present new information, either in a large block, as in Body and Soul, or in bits, as in J. Edgar. Other flashbacks present old information, mostly to remind us of something we’ve already seen or heard that’s relevant to the moment. Occasionally, a flashback is both a reminder, because it shows us something we’ve seen before, and a source of new information. It’s very common for mystery films and TV shows to use a flashback to an earlier scene in order to fill in whodunit, and how it was done.

Let’s call this reminder involving new information a replay. A replay goes beyond a simple repetition by showing the action in a new light—from a different character’s perspective, or including information that was omitted on the first pass. The latter happens in J. Edgar, when we see earlier scenes corrected to give credit to the actual agents involved.

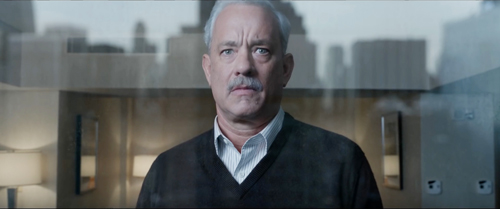

Replays and other techniques of repetition are given a remarkably central role in Todd Komarnicki’s screenplay for Sully. It’s not surprising because the core incident, Chesley Sullenberger’s landing of a damaged airliner on the Hudson River, is said to have consumed only 208 seconds. There would have been many ways to tell this story; a straight linear account, as in United 93 (2006), must have been a tempting option. Instead, Sully concentrates on the heroic pilot, whose action was supported by comradeship with his co-pilot, and the collective spirit of the passengers, crew, and first responders. In order to add conflict, Komarnicki and Eastwood build up the drama of the National Transportation Safety Board’s inquiry into the landing. The members of the board are initially presented as skeptical antagonists, although by the end, they gracefully acknowledge that the plane could not have returned to the nearest airfields.

The emergency landing is presented in flashbacks, framed by the ongoing investigation. But the film opens with the plane crashing into Manhattan skyscrapers.

It’s revealed as Sully’s nightmare, which haunts him after the rescue. The sequence anchors us firmly in his consciousness; we’ll be more attached to him than to any other character. As an anxiety dream, it presents a sort of what-if version that retrospectively justifies his decision to land on the Hudson. But its emotional tenor reveals his consistent worry throughout the plot that the authorities will judge that he put the passengers’ lives at risk unnecessarily.

Later another version of this Manhattan crash plays out not as a dream but as a waking fantasy, as Sully looks out of a skyscraper window. The scene suggests that he’ll never be able to see this cityscape without imagining the catastrophic alternative scenario. The same fraught feelings crop up in another fantasy passage, when he imagines a TV commentator asking: “Sully: Hero or fraud?” It isn’t just the accusation from outsiders that worries him. He questions what he’s done too. It’s important that the film give Sully enough self-doubt to build our sympathy and to make his final vindication all the more deserved.

Having given us dream and daydream, the filmic narration also gives us memory, in the form of flashbacks to Sully’s younger days, when he fell in love with flying and graduated to testing aircraft in dangerous situations. These affirm his expertise while also showing the quiet determination that can seem a little dour. (He’s told by his flight instructor to smile more.) This serious older man was also a serious young one.

From the start, the Board’s inquiry sets up the need for simulations to check Sully’s decisions. The first set are computer-based, and Sully requests that pilots also execute simulations. The human simulations will become crucial points of conflict at the climax.

One of Sully’s phone calls to his wife back home triggers the first flashback to the fateful day of 15 January 2009. This is launched about 27 minutes in, marking the shift to what Kristin calls the Complicating Action section of the plot. We’re shown Sullly’s arrival at the airport, the assembling of the passengers, and the takeoff. Soon enough, a flight of birds hits and the plane is damaged. Sully and copilot Jeff Skiles radio the air control center.

At this point, our attachment shifts to the controllers, and we hear the pilots trying alternative options. Other aircraft in the area see the plane go down, and the controller is relieved to learn that the landing was successful.

Crucially, we aren’t in the cockpit throughout this first run-through of the landing. Although the film celebrates Sully, the narration initially shifts our attachment to others trying to help him. This tactic also allows the filmmakers to save the most dramatic version of the landing for later replay.

The second major flashback, triggered by Sully brooding in a pub, shows the rescue operation. There’s a replay of the plane’s descent, again refracted through observers. Some are eyewitnesses, but mostly we see coast guard people who leap into recovery mode.

We alternate those views with vignettes of the passengers evacuating, overseen by Sully’s apprehensive effort to make sure all survive. Even after the passengers have been taken aboard the rescue boats, Sully can’t calm down until he’s told that the tally shows that everyone is safe.

The end of the flashback, which I’d say constitutes the Development section in Kristin’s model, introduces the crucial motif of timing, which will be Sully’s defense at the last hearing.

We’ve registered the water landing from the perspectives of the air-traffic controller, of eyewitnesses on the ground, of the first responders, and of the passengers. But what were the 208 seconds like inside the cockpit? This will be the business of the film’s climax, and several versions of it will be presented.

At the final hearing of the NTSB, a public one, the Board members report on the computer simulations. Those indicate that the plane could have flown back to La Guardia or on to Teterboro for a safe landing. Then the Board, through video contact, shows pilots simulating the alternatives, instant by instant starting from the bird strike. These reenactments are a bit like Sully’s nightmare and daytime fantasy, in that they present grim alternative scenarios—hypothetical replays, we might say. Both confirm the computer’s conclusion that the water landing wasn’t necessary.

A fair amount of suspense has been built up by these reenactments. The audience hasn’t seen everything that happened in the cockpit during the crisis. How can these simulations be challenged?

Sully raises the crucial point that the pilots in the simulation had foreknowledge of what they were to do. (In cognitive-science jargon, they were primed.) In fact, the Board admits, the pilots were permitted to practice the maneuver several times. Sully requests that time be added to the simulation, as a way to reflect the real conditions of unexpected decision-making.

So the pilots run the simulations again with a 35-second lag. Both the La Guardia and Teterboro options now lead to crashes. Sully and Skiles are vindicated. Finally, we get a full-blown replay of the critical action in the cockpit, thanks to the Board’s playing of the flight-box recorder. We hear the pilots’ conversation while the film flashes back to show Sully and Skiles facing the crisis.

Thanks to editing, the 208 seconds from “Birds!” to safe landing gets expanded a little in this replay. (By my count, it runs about 330 seconds.) And we aren’t wholly confined to the cockpit visually, as we can trace the plane’s progress from outside. Basically, though, we’re attached to the two men, sometimes through optical POV shots. Although we saw the early phase of the pilots’ routine safety responses in the first long flashback, now we see the whole process, culminating in Sully’s decision to land on the Hudson.

What might have been a strenuous exercise in padding, replaying the crucial moment just to stretch the action out, becomes a strategic way to balance individual and collective effort. The first two long flashbacks stress the roles of the air-traffic controller, the crew, the passengers, and the first responders. In this respect the heroism is spread out, showing a collective effort to save the situation. Only at the climax does the film confirm what many witnesses have said from the start—that Sully deserves to be called a hero. The NTSB officials pay tribute to him as the x-factor, the crucial figure in the equation. But he demurs: “It was all of us.” The theme of group accomplishment is made tangible by the film’s play with plot structure and narration.

The replay flashback wasn’t unknown in silent film, and sound examples include The Canary Murder Case (1929) and The Witness Chair (1936). Nevertheless the replay becomes quite elaborate in the 1940s, with Mildred Pierce (1945) being a particularly intricate example. It’s clearly an idea circulating through the filmmaking community: Cukor wanted a replay for A Woman’s Face (1941) and Mankiewicz wanted one for All About Eve (1950). (He got one in the self-produced Barefoot Contessa, 1954.) An almost fussy example can be found in the British flashback film, The Woman in Question (1950). Since then, the replay has been a rich secondary resource for Hollywood. Its widespread revival, and repurposing, in modern cinema reminds me of a remark made by André Bazin.

Sometimes Bazin’s reference to “the genius of the system” is taken as praise for the Hollywood studio system as an economic enterprise. I don’t read it that way. I think he was referring to the fecundity of a particular storytelling tradition.

The American cinema is a classical art, but why not then admire in it what is most admirable, i.e. not only the talent of this or that filmmaker, but the genius of the system, the richness of its ever-vigorous tradition, and its fertility when it comes into contact with new elements.

Bazin gives as examples of such “new elements” the commentary on American society to be found in films like Bus Stop and The Seven Year Itch. In such films, “the social truth . . . is not offered as a goal that suffices in itself but is integrated into a style of cinematic narration.” Sully does much the same thing. Seizing on the bare incident of Captain Sullenberger’s landing and its reception by the public, the filmmakers have integrated it into a narrative pattern that is at once traditional and novel.

It’s this interplay of narrative convention and innovation I try to trace across a single period in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The citation of Bazin comes from “On the politique des auteurs,” in Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Harvard University Press, 1985), 258.

I discuss network narratives in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 9-103, and more extensively, drawing examples from world cinema, in “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 189-250. On this site, see this entry on Grand Hotel (1932), this one on Life without Principle (2011), this one on some examples from the 2000s, and another about Babel (2006). One from last winter compares network narratives to films with one or two protagonists. See also Peter Parshall’s book Altman and After (Scarecrow, 2012). Want to see a combination of network narrative and maniacal replays? That would be Vantage Point (2008), which I once intended to write about here before a trip to Asia deflected me. . . .

To-camera address in The Wolf of Wall Street is considered here. In another entry I discuss traces of the would-be replay in All About Eve. “Play It Again, Joan” considers purely auditory replays. To compare a replay with a film’s first iteration, you can check my analysis of Mildred Pierce and the video therein. I discuss a pseudo-replay in The Chase (1946); it’s weird, but that’s the Forties for you.

Other examples of modern assimilations of 1940s techniques are discussed in this entry on fragmentary flashbacks and this entry on Tarantino. And of course there’s the labyrinth of linkages we find in The Prestige. For other relevant entries, check the category 1940s Hollywood.

Jersey Boys.

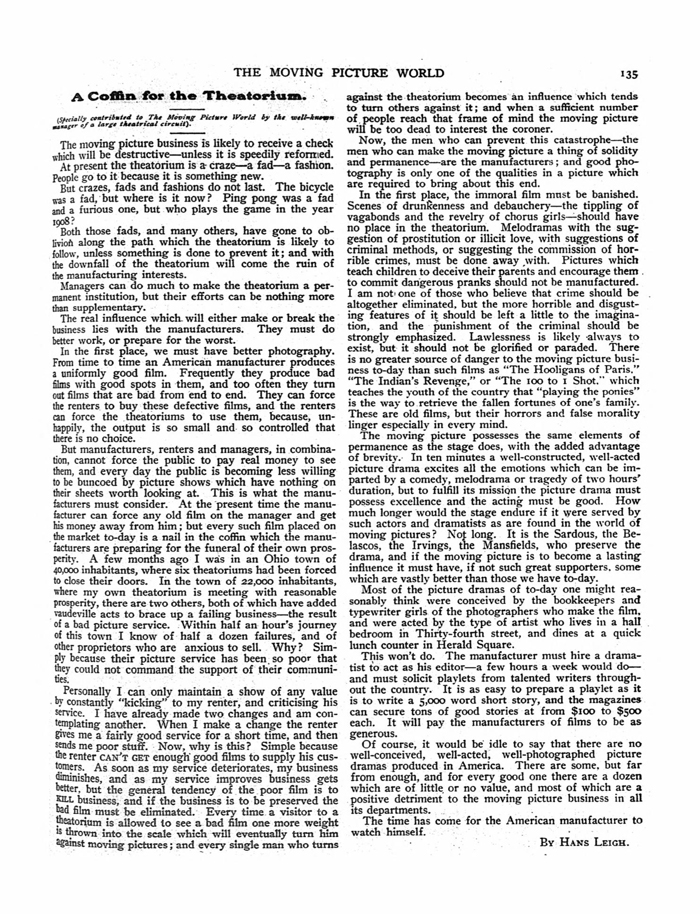

The end of Theatoriums, too

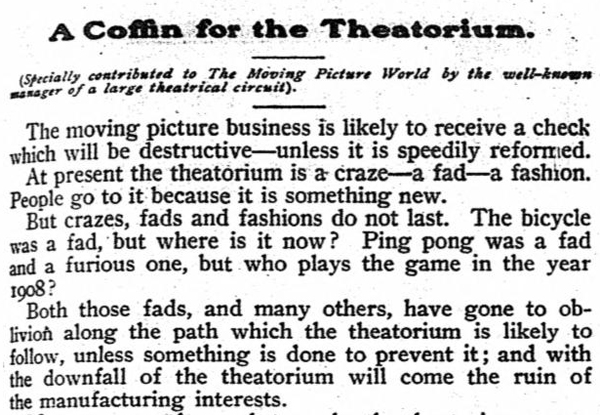

Moving Picture World (February 1908), 135.

DB here:

Vis-à-vis the last post, all of three hours ago, Alert Reader and arthouse impresario Martin McCaffery sends the above.

Actually, it’s much in the spirit of current jeremiads: Movies and their theatoriums better shape up, or they’ll be finished–like bicycles and Ping-Pong.

History is so cool. Full text here and below. There’s also a 1908 rebuttal, in the spirit of movies-are-doing-just-fine-thanks, here. Both courtesy the prodigious Lantern.