Archive for 2016

Is there a blog in this class? 2016

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991).

KT here–

Another year has passed, and Observations on Film Art is approaching its tenth anniversary. The blog was never intended as a formal companion to our textbook Film Art: An Introduction. Basically we write about what interests us. Still, many of our entries use concepts from the book, and we hope that teachers and students might find them useful supplements to it.

As each summer approaches its end and teachers compose or revise their syllabi, we offer a rundown, chapter by chapter, of which posts from the past year might be relevant. (For previous entries, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015.) For readers new to the blog, these entries offer a way of navigating through the site.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Film projection made the national news in late 2015 when Quentin Tarantino released his new film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film. Only 100 theaters in the USA, most of them specially equipped with old, refurbished projectors, could show it that way. We went behind the scenes to see how the theaters coped in THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth and THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing.

This year the studios took tentative steps toward instituting The Screening Room, a system of streaming brand-new theatrical films to people’s homes for $50. Whether or not this service succeeds, it represents one new distribution model that Hollywood is exploring to cope with the increasing delivery of movies via the internet. See Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop.

Popular film franchises can go on generating new products and influencing other films for years. We examine the lingering impact of The Lord of the Rings thirteen years after the third part was released in Frodo lives! And so do his franchises.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In this chapter we put considerable stress on the concept of narration, the methods by which a film conveys story information to the viewer. There is no end to the ways in which narration can be structured. Often one of the characters in a film can to tell us what happened. . . even if that character is dead. This, as we show in Dead Men Talking, is not as rare as one might expect.

The Walk combines narrative and genre in an unusual way. The first part is a romantic comedy, the second a suspense film, and the third a lyrical piece. We suggest why in Talking THE WALK.

The way a film tells its story can vary considerably depending on whether it has a single protagonist, a dual protagonist, or a multiple protagonist (as in The Big Short, bottom). We examine some of the differences in Pick your protagonist(s).

Looking back over our blog as we passed 700 entries early this year, it occurred to us that several entries discussing principles of storytelling could be arranged to create a pretty good class in classical narrative strategy. We made up an imaginary syllabus in Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101. No tuition charged.

With the very end of the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise–the release of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third Hobbit film–we discuss the strengths of the film and the plot gaps left unfilled in A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

To celebrate Orson Welles’s 101st birthday, we examined some of the sources for some of the techniques used in Citizen Kane, a film we analyze in detail in Chapters 3 and 8. See Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts.

In Hollywood it is a common assumption that the protagonist(s) of a film must have a “character arc.” Filmmaker Rory Kelly, who teaches in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, wrote a guest entry for our site. Rory analyzes the character arc in The Apartment, with examples from Casablanca, Jaws, and About a Boy as supplements. See Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly.

James Schamus’ Indignation, an adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, draws on novelistic narrative devices not in the original. In INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film, we suggest that those devices first became standard in cinema during the 1940s.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

Teachers and students always want to us add more about acting to our book. It’s a hard subject to pin down. We introduce the great stage actor Mark Rylance, who was largely unknown outside the United Kingdom before he won an Oscar for Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, and discuss how he achieves his expressively reserved performances in that film and the series Wolf Hall. See Mark Rylance, man of mystery. (Above at left, on set with Tom Hanks and Spielberg.)

In an era when most staging of actors in movies follows a few simple conventions, we examine the more imaginative ways of playing a scene on display in Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950) in Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers young and old.

Continuing with the theme of acting and staging, our friends and colleagues, Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have put a revised version of their in-depth study of silent-cinema acting online for free. Learn about it and the enhancements that internet publishing has allowed in Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

We look at the visual style of Anthony Mann’s Side Street (1949) and show how a simple, seemingly minor technique like a reframing can create a strong reaction in the spectator. See Sometimes a reframing …

Framing a composition is one of the most basic aspects of cinematography. We discuss centered framing, decentered framing, balanced framing, framing in widescreen movies, and particularly framing in Mad Max: Fury Road (above) in Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom.

In a follow-up entry, we discuss framing in the classic Academy ratio, 4:3, with emphasis on action at the edges of the frame: Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket.

Chapter 7 Sound in Cinema

For the new edition of Film Art, we had to eliminate our main example of sound technique, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige. But we put that section of the earlier editions online. THE PRESTIGE, one way or another takes you to it.

For those who have been looking for examples of internal diegetic sound, we take a close look (listen) at a sneaky one in Nightmare Alley: Do we hear what he hears?

The fact that the protagonist narrates The Walk in an impossible situation, standing on the torch of the Statue of Liberty and talking to the camera, bothered a lot of critics. We suggest some justifications for this decision in Talking THE WALK.

We offer brief analyses of the Oscar-nominated music from 2015 films in Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Many different filmic techniques can serve similar functions. Filmmakers of the 1940s had a broad range to choose from when they portrayed dead people, or Afterlifers, on the screen. We look at how their choices affected the impact of the scenes (as in Curse of the Cat People, above) in They see dead people.

Style and form in three films of Terence Davies: Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes; and especially his most recent work, Sunset Song. See Terence Davies: Sunset Songs.

Style and form in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, on the occasion of its magnificent release by The Criterion Collection, in A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY: Yang and his gangs.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated

Leo Hurwitz’s little-known documentary, Strange Victory (1948) has recently come out on Milestone’s DVD/Blu-ray. Released shortly after the end of World War II, it suggests that the Nazi atrocities were only an extreme instance of the cruelty of racism. We discuss the film and its relevance to the current political situation in Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948).

Experimental filmmaker Paolo Gioli makes films without cameras, or at least, he cobbles together pinhole cameras of his own from simple materials. The results are remarkable. We describe his work and link to a recent release of his work on DVD in Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

The eleventh edition of Film Art contains a new sample analysis of Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom. We discuss some additional aspects of the film in Wesworld.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

At the end of each year we avoid doing a standard ten-best list by choosing the ten best films of ninety years ago. For 2015, we dealt with The ten best films of … 1925 (including Frank Borzage’s Lazybones, above). It was a very good year.

A rare French Impressionist film, Marcel L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine, has been released on DVD/Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. We discuss the film and its background in L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema.

Film Adaptations

Our eleventh edition offers an optional chapter on film adaptations from a wide variety of art forms and even objects.

For thoughts on popular female novelists whose books were adapted into films during the 1940s and 1940s (and who sometimes became screenwriters), see Deadlier than the male (novelist).

Adaptations can be made from nonfiction as well fictional books. We look at how Dalton Trumbo’s life was made into a biopic in Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO.

In a series of entries, we have commented on the adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit into a three-part film. For an analysis of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third part, see A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump? (Links in that entry lead to earlier posts on this subject.)

As always, we have blogged about some recent books and DVDs/Blu-rays. See here (Vertov, sound technology, 3D), here, (Kelley Conway’s new book on Agnès Varda), here (experimental films, the first Sherlock Holmes, the Little Tramp), here (Tony Rayns on In the Mood for Love), and here (on some older foreign classics that have finally made it to home video in the USA, primarily those of Hou Hsioa-hsien). The publication of the eleventh edition of Film Art led us to look back on how it was written and some of the ideas that went into it. We took the occasion to introduce our new co-author, Jeff Smith. See FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

We were also profiled in Madison’s local free paper, Isthmus, by Laura Jones, reporter and filmmaker. She read Film Art as a student.

The Big Short (2015).

INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film

Indignation (2016).

DB here:

As I finish my book on 1940s Hollywood storytelling, I see that period’s influence all over the place. (Actually, that’s part of the book’s point.) One thing that filmmakers did back then, I think, is make cinema more “novelistic.” It’s not just that they took stories from novels, though they certainly did. They also made much greater use of storytelling devices that had become common in literature both high and low.

Many of these techniques I’ve talked about in other entries. There were, of course, flashbacks—not new to the Forties, but now much more frequent than in the Thirties. There was also the rise of voice-over commentary, like the narrating voice of fiction. It might be the voice of an objective narrator, as in Naked City (1947). Or it might be the voice of a character, either telling the tale to another character, or recalling events purely in his or her mind.

Other types of subjectivity came forward too, such as dreams, daydreams, and hallucinations. Filmmakers of the 1930s were inclined to tell their stories objectively, through concrete behavior. But thanks to imported and revised literary strategies, many Forties films gain a greater density and interiority. Compare, for example, the 1931 Waterloo Bridge with the 1940 one.

One thesis of my book is that filmmakers of the Forties consolidated these strategies in a way that became central to modern movie storytelling. That seemed to me to be confirmed when I saw James Schamus’s directorial debut, Indignation, now or soon playing at a theatre near you. Because of his skill as a screenwriter, I expected an intelligent adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, but I also hoped to learn more about the expressive resources of contemporary cinema. I wasn’t disappointed.

Indignation’s core story involves Marcus Messner, studious son of a New Jersey butcher who goes off to a Midwestern college. Stuffed with ideas and ambitions, Marcus is intellectually worldly but socially and sexually naïve. If he weren’t in college, he’d be drafted to fight in the Korean War. Instead of fitting smoothly into academic life, he finds himself confused by Olivia Hutton’s calculated sexuality. In addition he struggles with an overprotective father and the puritanical, hamfistedly Christian, regimen of 1951 campus life.

To talk about what I find exciting and instructive in the film, I have to presume you’ve seen it. So what follows is filled with spoilers.

Sticking to one causal line

Like the book, the film is an exercise in restricted point of view. That involves not simply the voice-over commentary that weaves in and out. (In a film, that technique doesn’t guarantee restriction the way first-person narration would in a novel. Movies can be more promiscuous in breaking with what one character thinks and knows.) And the restriction isn’t wholly a matter of a subjective plunge either, though we do get Marcus’s dreams and fantasies and some fragmentary flashbacks.

No, what makes Indignation intriguingly “novelistic” is a matter of attachment. We’re simply with Marcus through almost the entirety of the movie. We know only as much as he knows. This means that we learn about certain things when he does. His father’s breakdown back home is conveyed through phone calls. At the climax, his mother’s visit to him in the hospital reveals that she’s considering divorce. An alternative narrative strategy would be to shift from scenes with Marcus to scenes elsewhere, say back home in New Jersey or in Olivia’s dorm. This “omniscient” option is more common throughout American film history; we see it in the crosscutting between CIA malefactors and poor David Webb in Jason Bourne.

Restricted narration isn’t the only way to generate mystery, but it’s a reliable one. By attaching us to Marcus’ range of knowledge, Indignation creates mysteries, chiefly around Olivia. What has made her behave as she does? She never offers a full explanation, but in some scenes she tells more about her parents and in a crucial confession she confesses her alcoholism, a suicide attempt, and a period in treatment.

During this confession, Schamus finesses the showing/ telling problem in an intriguing way. There are good reasons, I’ve suggested before, to let such monologues play out in the space and time of the scene. Telling is sometimes more vivid than showing. But Schamus has chosen to show as well as tell, by providing quick flashback illustrations of what Olivia recounts to Marcus.

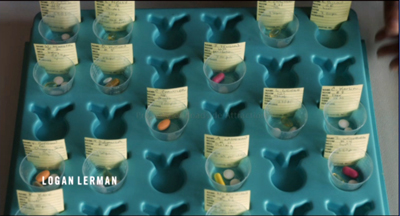

What interests me is that these images from the past have an in-between status. They’re neither straightforward and neutral, nor Olivia’s own viewpoint, nor exactly Marcus’s imagined version of what she’s telling him. For instance, the straight-down, somewhat diagrammatic and clinical framing of some of them calls to mind the film’s first shot, also associated with Olivia’s health: the pill case in the care facility.

Likewise, the shot of Olivia in a straitjacket, framed off-center in a way few other isolated long shots in the film are, has an abstract quality that suggests an image lying somewhere between her memory and Marcus’s imagining of her situation—without making it wholly subjective. (In the early 1950s, it’s plausible she was indeed treated this way.)

At the climax, we get even less information about Olivia’s situation. Before Marcus can break off with her, she simply vanishes. Marcus will never find out what became of her. For him, if not for us, the mystery is permanent.

Not that he doesn’t try to communicate. This is one role of the voice-over in which he muses on his past and, more ambitiously, on the role of cause and effect in life. As a follower of Bertrand Russell, he’s evidently pondering Russell’s idea of “causal lines.” Ironically, though, Russell’s inferential model of causality doesn’t help Marcus figure out what happened to Olivia.

But from where is Marcus speaking? Quite likely, from the Afterlife.

Dead narrators drift through 1940s cinema. Philip Roth was ten when The Human Comedy (1943) featured a deceased father returning to his small-town family, and eleven when The Seventh Cross (1944) gave us an executed prison-camp escapee who shadows one of his mates. So Indignation, set in the year after Sunset Boulevard (1950), seems perfectly in keeping with this trend. But these other films announce the voice-over’s posthumous status right away. Schamus does something a bit different.

In the source novel, Roth lets Marcus suggest that he’s dead about a quarter of the way through. Schamus’s screenplay drops hints that are, I think, fully noticeable only in retrospect. He creates a surprise that in turn motivates one of the two frames that surround the 1951 story action.

The front end of the inner frame is a brief combat skirmish in South Korea. A GI is pursued into a dark, nondescript building by a North Korean soldier. The action is difficult to discern, but we can see that the Korean is shot. Did the GI escape? The combat scene will be partially replayed near the film’s end, closing the frame the first one opened. The GI will be revealed as Marcus, who is dying from a bayonet thrust.

This isn’t merely a trick. In the 1940s filmmakers realized that some stories, if told chronologically, begin in rather slow and uninvolving fashion. But starting at a crisis late in the story’s causal chain, and then flashing back to what led up to it, can arrest our attention. Think of what The Big Clock (1948) would be like if we started not with the hero dodging around corridors trying to elude the police, but with his mundane office routine earlier that morning. So instead of starting with Greenberg’s funeral, Indignation grabs us with a brief and enigmatic piece of life-or-death action.

1940s frames are more explicit about the framing situation than the combat incident in Indignation. Yet Schamus evidently didn’t want to show Marcus lying there dying and reflecting on his life and leading into the film as a whole: too on-the-nose, and perhaps too obviously fatalistic. The shift to the Jonah Greenberg funeral frees the story action from what Henry James once called “weak specificity.”

There’s also the possibility that Marcus survives; we don’t see him die, even in the finale of the skirmish. The fact that the film can equivocate about whether our narrator is alive or dead emerges as a fresh treatment of the Afterlifer convention.

By raising the possibility of a dead narrator early on, Roth may make us view Marcus’s actions with more detachment, sub specie aeternitatis. The film version, I think, gets us more emotionally invested in Marcus, and this makes the eventual possibility (for me, the likelihood) that he has died more wrenching.

More than Marcus

Even in the enframed 1951 story action, our attachment to Marcus’s range of knowledge isn’t complete. For one thing, there are ellipses—most notably, the crucial scene in which he asks Olivia on their first date. There are also moments in which we run ahead of his awareness. When his mother meets Olivia, Schamus has controlled his actors’ eyelines so that even in a two-shot we’re not looking at the hero but rather at Mrs. Messner, who spots the girl’s wrist scar.

This is sharp visual storytelling. Marcus is unaware of his mother’s observation, but we’re prepared for her later admonition that he’s getting involved with a woman who will bring him misery. (Marcus: “She slit one wrist.” Mrs. M.: “One is enough. We have only two, and one is too much.”)

We’re also a beat ahead of Marcus in one neat shot that shows him stepping onto the quad as he’s facing expulsion. We see his future before he does; the marching ROTC students in the background catch our notice before a rack-focus brings him up to speed.

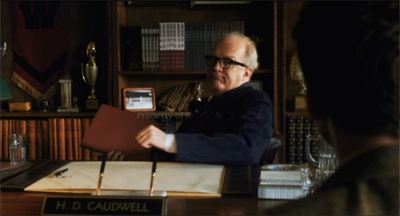

We’re also invited to see parallels that pry us a bit away from Marcus’s immediate experience. At two crucial moments, the adults trying to intimidate him—Dean Caudwell and his mother—come around behind him to keep wheedling.

The know-it-all debater has a chance when fighting face to face, but he crumbles when authority steers from behind.

Above all, our attachment to Marcus is qualified by a second frame, the one that wraps the whole fiction. This is wholly Schamus’s invention—a nested structure of the sort characteristic of 1940s films. At the very beginning and end of Indignation, we see an elderly Olivia in a care facility staring at the wallpaper dotted with a pattern of flowers in a water carafe. The image (also on a skirt she wears in the college portion) harks back to her impromptu bouquet for Marcus in the hospital.

But of course we’re inclined to ask: How likely is it that such a pattern would be used on wallpaper, and would it so neatly coincide with an item in Olivia’s past? We could then ask whether the pattern is in her imagination. (There is a sort of blurring and refocusing on the pattern, suggesting her optical viewpoint.) And since her scenes in the facility bookend the entire film—the Korean War frame, which in turn encloses the Winesburg College days—we might ask whether everything we’ve seen isn’t a product of her fantasy.

I’m not inclined to say that she has made up the whole movie. Indeed, if the wallpaper pattern is her projection, it would have to be so not just in her optical POV but also in the wider shot of her, the first image we get of her as an old woman.

Maybe this room, Caligari-like, is a total projection of her memory? More likely, it’s objectively there but triggers her recollection of Marcus. I’m still uncertain, but it does seem that giving Olivia the ultimate framing for the tale via their shared moment with the flowers suggests that Marcus, who at the end of his last monologue is calling out to her, has somehow finally made contact.

In any event, a purely formal cadence, completing the ABCBA structure and revisiting an ambivalent motif in the film, can balance, in aesthetic terms, the absence of answers to questions posed in the story world. This appeal to geometrical architecture and symmetrical construction is, since Henry James, another novelistic convention: art’s order can frame, if not completely account for, the disorder of life as it’s lived.

Goliath wins

The sequence that has everybody talking is the sixteen-minute two-hander between Marcus and Dean Caudwell. It’s in the book, but Schamus and his players have brought to life the clash between idealism and suave, well-practiced bullying.

Straddling the film’s midpoint, this scene enacts the old proverb. “Old age and treachery trumps youth and skill.” It starts with a simple bureaucratic issue: Marcus’s transfer out of the dorm to a shabby, solitary room. This incident leads Dean Caudwell to charge him with stubbornness, lack of compromise, secrecy about his Jewish identity, friction with his family, intellectual arrogance, and cowardice. The whole cascade is punctuated by the Dean’s intermittent requests to stop calling him “sir.” It’s a verbal boxing match with Marcus gamely fighting on after quite a few low blows. Nobody who read Why I Am Not a Christian in their youth (as I did) can fail to be roused to self-righteous fury by Caudwell’s calm, close-minded innuendo.

Still, in such duels dialogue and performance need to be orchestrated with framing and cutting. Steve McQueen’s solution in Hunger (2008) is the use of a sixteen-minute profile long-shot, followed by a cut in to Bobby Sands’ hand picking up his cigarettes, and then a very tight close-up of his face as he continues speaking.

The interruption of the long take gives special prominence to a shift in the conversation, when Sands recalls his childhood. Later shots revert to shorter shot/ reverse-shot exchanges.

So framing and cutting can articulate phases of the drama. This Schamus does very carefully in the Indignation scene. To abbreviate:

Phase 1: More or less businesslike and polite: Why couldn’t Marcus compromise with his roommate? 180-degree cuts, with framing favoring Dean Caudwell–centered and dominating Marcus.

Phase 2: Caudwell gets personal. Why didn’t Marcus identify his father as a kosher butcher? Eventually he’ll accuse Marcus of intolerance. Here a fairly lengthy profile shot reminiscent of Hunger gives way to shot/ reverse-shot.

Phase 3: More personal probing: How does Marcus get along with his family? What about his sex life? And religion? After more shot/reverse shot, Marcus, sweating and feeling sick, rises to defend himself in close-up. That calls forth the closest shot yet of Caudwell.

Phase 5: Caudwell says Marcus’ sophistry will make him a fine lawyer. He comes to stand behind Marcus, putting his hands on his shoulders. Then he sits beside him, to drill in still more. Marcus, shaky, asks to leave.

Phase 6: At the door: Marcus is feeling sick. The dean asks if he’d like to play baseball. Finally Markus collapses and starts vomiting.

Schamus has saved shot/ reverse shot for when the scene heats up, and saved his close-ups for when things reach a pitch. This reminds us, as the Hunger scene does, that if you’re going to use a standard technique, hold off until it will do the most good. Ditto for the low angle on Marcus throwing up; that comes with more force if we haven’t already had low angles before. Schamus has let his cutting and shot scales amp up the drama without the crushing emphasis supplied by so many directors. Yes, I’m thinking of the barrage of close-ups in every dialogue scene of Jason Bourne. (Thanks to Paul Greengrass, Tommy Lee Jones’s facial contours qualify for Federal Drought Relief funds.)

I think that Indignation will be studied for years as an intelligent adaptation of Roth’s novel, but it ought also to be admired as a well-crafted work in its own right. It finds fresh ways of molding fiction techniques to the demands of cinema in general and Hollywood tradition in particular. And the film reminds us—or me, at least—how much contemporary filmmaking owes to the consolidation of “novelistic cinema” seventy years ago.

Thanks to James Schamus, Gustavo Rosa, and Lauren Hynnek for information and assistance, . For more on James’s career, see our entry.

Students of literature might find another novelistic analogy in Olivia’s explanation of her suicide attempt. It somewhat resembles the technique of free indirect discourse, when the third-person authorial voice adopts the language and syntax of the character’s thought. Roth employs this in the third-person tailpiece of his novel. Instead of “If only I hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for me at chapel!” we get “If only he hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for him at chapel!” Is it possible to have a cinematic equivalent: an objective vision that is pervaded by the character’s state of mind? Pasolini thought so, and suggested Red Desert, Before the Revolution, and Godard’s films as examples of it. Perhaps this flashback sequence counts as a case of Pasolini’s “free indirect subjective.”

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I briefly discuss the resurgence of 1940s storytelling strategies in recent studio cinema (pp. 72, 83). A general discussion of my interest in 1940s narrative is here. Elsewhere I make the case for Tarantino reviving 40s formats; for the importance of Afterlifers in the Forties; for nested narratives like that of Indignation; for replays that provide new information; and for the blurring of subjective and objective in Nightmare Alley.

For more on novelistic strategies in film, see “Watching a movie, page by page” and Kristin’s entries on the Hobbit films, all linked here.

Indignation.

Frodo lives! and so do his franchises

Given the saturation of fantasy, sci-fi and superhero films we experience today, not to mention how frequently we quote from Lord Of The Rings, it bears reminding now and again (not too obsessively, mind) just what a game changer Lord Of The Rings was.

Jordan Adcock

Kristin here:

A little over ten years ago, in April 0f 2006, I finished the manuscript of The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007). Given that I had previously written books and essays on films by such auteurs as Sergei Eisenstein, Jacques Tati, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Renoir, and Robert Bresson, those who knew my work were perhaps bemused by this change of direction.

I had decided to tackle this project, which proved to be an enormous but richly rewarding one, in 2002, after the release of the first part of The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring (December, 2001). Already it was apparent to me that Peter Jackson’s adaptation would be an enormously influential film, to the point where, whether or not one likes the movie itself, it would be among the most historically important films ever made. New Line used the internet to promote it at a time when it was still not common for a film to have its own studio-created website. The cooperation between the filmmakers and the video-game designers was unprecedented. The extended-version DVD releases, arriving only five years after the introduction of the format, had unique depth and breadth. The impact of its technical innovations, particularly in digital special effects and color grading, was enormous. The film’s success boosted the many independent producers around the world who had largely financed it. Not to mention the ways in which the movie transformed New Zealand through tourism, a small but sophisticated and thriving film industry, and a surge of national pride. The film and the franchise impacted the Hollywood industry in almost any way one could imagine.

In 2002, to believe all of this was going to happen and to commit to spending time, money, and effort in researching all these topics required something of a leap of faith. It was one I was confident in making. Uncharacteristically for a historian, I made some predictions about the lasting power of LOTR and its franchise. This risk was inevitable, given that I was writing about a lengthy ongoing event, one which clearly would last far into the future. The book begins: “The Lord of the Rings film franchise is not over, not will it be for years.” [p. XIII] Later I specified:

The franchise is not nearly over. Middle-earth-themed video games continue to appear. Additional licensed toys and collectible items are still being brought out. Fan activity remains lively in cyberspace and the real world. The phenomenon has reached into international culture in ways that go far beyond the commercial confines of the franchise. Politics, education sports, and religion all reflect the influences of the film. An extinct race of tiny people discovered on a Pacific island was instantly dubbed “hobbits” by headline writers and even the scientists who discovered them. [pp. 9-10]

I was reminded of these claims by two recent events. First, last week’s Comic-Con included, as usual, a Weta Workshop booth, and, as usual, several of its popular limited-edition collectible figures from LOTR were debuted there. Second, on June 23, Jordan Adcock posted an intriguing article, “Can fantasy films escape Lord of The Rings’ shadow?” on Den of Geek. Yes, thirteen years after the release of The Return of the King (December, 2003) and ten after I ended the coverage in my book, the franchise goes on, as does the influence of Peter Jackson’s film. The number of products and tie-ins is far smaller than at the height of the films’ releases, but it seems to have settled down to a steady flow.

This combination suggested that it is an opportune time to point out that this film is still influencing the fantasy genre–perhaps too greatly–and that its franchise, though reduced, rolls on. I don’t think I was being terribly prescient in predicting all this, but it’s a bit of a relief to find out that I was right.

Collectibles, video-games, and more

Fans and collectors continue to purchase LOTR studio-licensed and fan-generated items of all sorts. Some of these are from the era of the film’s release, and some are new. A search on “Lord of the Rings” in the collectibles category on eBay generates 13,476 items, only a small percentage of which are related to products relating to the novel’s franchise or that of the 1978 Ralph Bakshi film. Some of the upscale and/or rare items sell for hundreds of dollars. There is still a demand.

In my book I made no effort to catalog all the products made to that point. In fact, I don’t think it would have been possible, unless I had had access to New Line’s records of its licensing contracts. Besides, that wasn’t part of the purpose of the book. In discussing licensed products, I was more interested in digital technology had affected what sorts of items were made. There was the motion-capture for the video games, for example. There were the DVDs–a format introduced as recently as 1997, the year when Miramax signed a contract with Saul Zaentz, thus obtaining the rights for Peter Jackson to make LOTR. (In Chapter 7 I give a little history of the introduction of DVDs and the part LOTR played in the studios efforts to move from rentals to purchases of home video.) There was the facial scanning of the actors for the action figures. There was, however, a dizzying array of hundreds, or more likely thousands of other, more conventional products licensed around the world. I once bought a lottery ticket in London not because I hoped to win a prize but because it was LOTR-themed and had a picture of Elijah Wood as Frodo on it.

Here I just want to give a few examples to show that New Line-licensed products are continuing to appear. I won’t include any Hobbit-based licensed products except in passing. Obviously the second trio of films extended the original franchise, but here I am only concerned with the longevity of the LOTR’s ability to generate more products and to influence the fantasy genre.

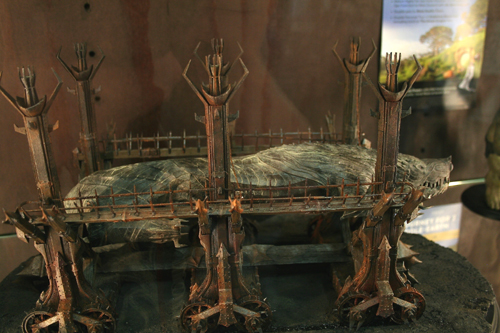

I mentioned the Weta Workshop collectible figures, which continue to be among the most popular products among devoted fans. The main fan-site, TheOneRing.net (Disclosure: I am a member of the staff) annually posts a video tour of the Weta booth at Comic-Con. This year’s video, Collecting the Precious-Weta Workshop Comic-Con 2016 Booth Tour (by TORn staffer Josh Long, about 18 minutes), lovingly moves over the glass cases containing the new items, including statues of Lurtz and Boromir enacting the latter’s death scene late in Fellowship. There’s also a big piece with the battering-ram, Grond. (I have a sentimental attachment to Grond, since it was the only one of the large miniatures made by Weta Workshop that I saw during my 2003 tour of facilities at Stone Street Studios. See above for the miniature version of the minature.) In watching the video, I didn’t keep count, but although over half of the figures are from The Hobbit, there are quite a few LOTR ones as well.

I have lost track of all the Middle-earth-based video games that have appeared since the last one the book covered: “The Battle for Middle-earth” (released on December 6, 2004, and, as far as I can tell, still in print). It was the fourth, and the first to concentrate on battles and strategies rather than on the plot of the movies themselves. By now here have been 22 of them, according to the “Middle-earth in video games” entry on Wikipedia, the most recent being “Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor” (2014). Its action takes place between that of The Hobbit and of LOTR. The total given above includes “Lego The Lord of the Rings.”

Lest one think that the only products are expensive ones aimed at the most enthusiastic core fans and dedicated gamers, I should mention that there are less pricey items. Inevitably, given the recent fad for adult coloring-books, there is one based on LOTR, list price $15.99, released May 31 of this year. (See top.) I expect a Hobbit one will follow. Warner Bros. has continued to bring out a film-based LOTR wall calendar each year. You can already pre-order the 2017 one, due out on September 15.

The posthumous career of J. R. R. Tolkien

As I pointed out in The Frodo Franchise, there has long been a franchise based around Tolkien’s original novels, which I discussed briefly. Lest we think that the film franchise must inevitably fade, it is worth noting that HarperCollins, Tolkien’s publisher, has kept the novel-based one going for decades after the author’s 1973 death.

There are, for example, numerous games like “The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game” (judging from the comments on Amazon, this must have appeared in 2013). HarperCollins publishes its own calendar, based on Tolkien’s work as a whole rather than just LOTR. Many do center on LOTR, often featuring the work of a major Tolkien illustrator. With The Hobbit having been published in 1937, however, its 80th Anniversary is being featured for 2017, also available for pre-order.

The Tolkien-based franchise items tend to be somewhat more dignified than many of the film-derived ones. This is especially true given that many of the products consist of new or reissued works by Tolkien.

Non-fans of the books may not be aware that the Tolkien publishing juggernaut goes on as well. These are not all cobbled-together variants of existing Tolkien works. Actual new texts by him appear at intervals as his son Christopher Tolkien slowly releases editions of unfinished manuscripts by his father. By now Tolkien has far more literary works published posthumously than during his lifetime, even if one does not count Christopher’s epic assemblage of the drafts for LOTR in the twelve thick volumes of “The History of Middle-earth.” (Tolkien was a notorious non-finisher and left behind many incomplete academic manuscripts as well.)

Earlier this year there appeared The Story of Kullervo, retold by Tolkien from the Finnish epic The Kalevala. Amazingly, a second is due this year: The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun (out November 3). These poems, both with historical and formal analysis by notable Tolkien scholar Verlyn Fleiger, are not for the broad audience of Tolkien fans, but they obviously generate enough interest among core devotees and scholars to be worth publishing.

Tolkien was a talented amateur artist who occasionally illustrated his own work, most notably The Hobbit, and drew many sketches and maps to help him visualize Middle-earth. The ones for LOTR were published last October as The Art of The Lord of the Rings.

There are also, of course, as many different new editions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as the publishers can possibly justify in some fashion. Every now and then a “gift edition” with new illustrations appears. The one tied to the 80th anniversary of The Hobbit is a version illustrated by Jemima Catlin, announced for early next year. On September 22, the long-delayed facsimile of the first edition of The Hobbit is due to appear. (As I recall, it was originally supposed to be part of the 75th anniversary celebration.) This facsimile is of considerable interest to fans and scholars alike, since Tolkien revised portions of the original tale. Most notably, it contains a very different version of the famous riddles scene between Bilbo and Gollum, in which the Ring is introduced in a way completely incompatible with the premises concerning it established later by Tolkien in LOTR.

Even bits of film and audio recordings of Tolkien occasionally resurface. On August 6 at 8 pm London time, BBC Radio 4 will broadcast of “Tolkien: The Lost Recordings.” This program is based around some newly rediscovered audiotapes of outtakes from the BBC’s 1968 documentary, Tolkien in Oxford.

Fantastic stories and where to find them

Jordan Adcock’s “Can fantasy films escape Lord of the Rings‘ shadow?” was inspired by the release and failure of Warcraft: The Beginning. He uses the occasion both to explain why the Jackson’s LOTR trilogy so dominates conceptions of filmic fantasy and to suggest how Hollywood might make films that won’t be compared to it and inevitably found wanting.

Alcock largely credits the film’s lingering impact to the depth and plausibility of its visual rendering of Tolkien’s invented world, Middle-earth. He spends some time describing how Tolkien, with his brilliant command of history and ancient languages, managed across his lifetime to develop a consistent, appealing continent with different races, languages, countries, and landscapes, as well as its own history. Jackson’s film manages to create “a fantasy world with both digitally-aided grandeur and a practical, lived-in feel […] Jackson recreates Tolkien’s precision of time and setting.”

Certainly the film’s production design, its New Zealand locations, and its cinematography creates a Middle-earth that impressed even the film’s harshest critics. Its treatment of the plot and characters, though less successful overall, stuck far closer to the novel than did the more recent Hobbit trilogy. (See here, here, here, and here for my comments on the strengths and failures of the three parts of the latter.) Long-time fans like me forgave LOTR a lot, including added schoolboy humor and Arwen supposedly dying, for the visuals and the music and the near-perfect casting. And, as David, who has never read Tolkien, remarked to me when we walked out of theater after his first viewing of Fellowship, “Well, it’s better than Star Wars!” Within the fantasy genre, LOTR probably is the finest achievement in modern American moviemaking. It is no wonder that subsequent films, even twelve years later, are seen by critics either as pale imitations of it or as failed attempts to create a different but equally dense and coherent fantastical world.

Alcock’s hints at how filmmakers might avoid such problems, but in the process he also admits that his solutions are nearly impossible to achieve. First, he points out that the fantasy world need not be created across several decades–and yet if it isn’t, it will not measure up.

Authors and screenwriters don’t have to go away and devote the rest of their lives [to] creating a universe as large and self-sustaining as Tolkien’s, but against such a brilliant creation done such justice, all other attempts feel a little short-termist.

I assume “done such justice” refers to Jackson’s film, the implication being that the screenwriters need not necessarily invent an entire world but might find it ready-made in a literary work. The fact that the Harry Potter serial achieved such fierce fan devotion and high BO seems to confirm that. Though not an impressive stylist, J. K. Rowling shares with Tolkien a remarkable imagination when it comes to making the Wizarding World vivid to readers. She also anchors it just enough in the real world to make it appealing and easy to relate to. Her novels bear almost no resemblance to LOTR, apart from the fact that the Dementors seem derived from the Black Riders. To a considerable extent, the strongest aspects of the film adaptation’s version of Rowling’s world parallels that of LOTR, superb design and excellent casting being perhaps foremost among them.

Creating an original screenplay with a similarly original world, however, seems an extremely tall order. To be sure, it is not impossible. George Miller’s first Mad Max film was not a fantasy but an action-revenge film shot on the cheap with an unknown star-to-be. Its success, probably based on skillful direction and an appealing actor, allowed Miller to transform Max’s ordinary Australian Outback into a distinctive fantasy world, a post-apocalyptic Wasteland. This, too, was fairly low-budget, requiring little more than a desert, a bunch of eccentric, souped-up vehicles, and a team of daredevil stunt performers. Even greater success allowed the third film a big Thunderdome set, some modest special effects, and a second star. Most recently Miller gained a blockbuster-size budget for special-effects, an Oscar-winning co-star, and a multiplication of the weird vehicles. This is not to say that Miller’s created world is as complex as Middle-earth, but it has a visceral sense of reality and a distinctive look that set it apart from any other films, fantasy or not. But how often can you generate a Mad Mad-style franchise from almost nothing?

Alcock doesn’t mention it, but fairy tales have become a fallback option for Hollywood fantasy. Such films, adapting the originals into versions aimed at adults, have largely failed to catch on. (Given the recent failure of The Huntsman: Winter’s War, we might suspect that the success of Snow White and the Huntsman was due largely to the star power of Kristen Stewart, fresh off the Twilight series.) Fairy tales are sketchy stories with fantastical events and minimal characterization. They usually either take place more-or-less in our world or else spend little time describing the look of Faerie.The designers are left to their own imaginations to create settings, most of which tend to be pretty conventional.

Following in the footsteps of the LOTR and Harry Potter filmmakers, finding a novel or other literary property with the built-in popularity to carry a big-budget special-effects film seems the way to go. Despite the plethora of fantasy novels since LOTR appeared in the 1950s, choosing just the right one has proven a considerable challenge.

New Line’s adaptation of The Golden Compass, the first book in Philip Pullman’s brilliant His Dark Materials trilogy, was creditable but not exciting enough to create a successful film, let alone a franchise justifying the expense. Perhaps the novel was too little known in the US. The same could be true for The BFG, another British children’s classic, which is doing even worse at the box-office. (The studio could at least have had the sense to rename it The Big Friendly Giant, though that probably would not counteract what I suspect was the public’s mistaken impression that the film was aimed strictly at children, and very young ones at that.)

Alcock carries on his speculations.

So how does a different fantasy film emerge from the shade that Middle-earth put over all the competition? Frankly, it’d have to be another masterpiece to do it. The problem is the cohesion of vision or sincerity of intent from these other would-be franchises.

“Make a masterpiece” is excellent advice but rather difficult to follow. It doesn’t always work, either. Probably the two best mainstream American films I saw last year were Mad Max: Fury Road and Pixar’s Inside Out. Both were fantasies. Neither, as far as I know, drew any comparisons to LOTR from critics or fans, so they did escape its shadow. Both were highly praised by critics and won Oscars. They may or may not be considered masterpieces in the long run, but they certainly could count as such in the context of contemporary Hollywood. One made lots of money and may eventually spawn a sequel, given Pixar’s growing penchant for such things. The other, given its hefty budget, probably did not make a profit, or at any rate not one that Warner Bros. would consider large enough to justify taking the franchise to a fifth film–unless, perhaps, Miller went for a lower-budget project. So making a masterpiece may help distance a film from LOTR, but it does not guarantee a more practical sort of success.

On the issue of vision or sincerity mentioned above, Alcock touches on one subject that I think helps explain why it’s extremely hard to produce successful fantasies that have not the slightest whiff of Middle-earth about them. His point also explains why we seem to be stuck in a dismal summer where every week the same set of interchangeable films come out. He discusses Hollywood’s failure to follow up the LOTR with a fantasy franchise that would avoid the inevitable comparisons to LOTR.

Just think of The Golden Compass, New Line’s attempt to create a new fantasy franchise out of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, much more lukewarmly received and whose box office led to New Line’s end as an independent company. Now there’s food for thought–would Warner Brothers [sic], who own New Line as all but a label today, have really greenlit Lord of the Rings in its ultimate form?

I think we know that the answer to that question is almost certainly no.

In fact, LOTR actually did fail to get greenlit in its final form, though at a different major studio. As I describe in The Frodo Franchise, in 1998 Harvey Weinstein was planning to produce LOTR as a two-feature film directed by Jackson and with a budget of $140 million. When the project was a year and a half into the scripting and design process, Weinstein was called into Michael Eisner’s office at Disney, parent company of Miramax. Eisner demanded that he cut the film to one feature, made for $75 million. Jackson balked and persuaded Weinstein to put the project into turnaround for two weeks. Famously Jackson pitched it to Bob Shaye, founder and co-president of New Line, a man who knew the value of a franchise with a built-in fan base and proposed to make LOTR as three features.

Today’s New Line, a mere production unit of Warner Bros., could not undertake such a project on its own accord, and today’s Warner Bros. surely would not. With studios opting for the most established formulas, a film comparable in originality to LOTR being made, especially with all three parts shot simultaneously, would be little short of a miracle.

The only circumstance in which such things can happen would be an adaptation of a book so successful that it virtually guarantees box-office success. Warner Bros. undertook the Harry Potter series under such circumstances, given the overwhelming popularity of the book. That the resulting series of films pleased established fans and new audiences probably owes much to the fact that Rowling took an active role in consulting on the scripting and other aspects.

Today’s largely unappealing lineup of summer films (and I am writing here of mainstream Hollywood films, not including such original independent fare as James Schamus’ excellent Indignation) has been punctuated so far by two entertaining and satisfying items: The BFG and Pixar’s Finding Dorie. Both fantasies, one an undeserved box-office failure, the other a record-breaker. Which goes to show, I suppose, that good, non-LOTR-influenced fantasy (whatever its box-office record) rests with auteurs and Disney/Pixar.

Is television the answer?

Like numerous other writers, Alcock offers Game of Thrones as a model for what fantasy films with richly realized worlds might be.

If Middle-earth has a “successor,” it’s Game of Thrones. Based on George R. R. Martin’s books, the TV series has come far closer to Lord of the Rings‘ immersive world-building and cultural impact than any other fantasy, and perhaps suggests how Lord of the Rings might be adapted today.

He is far from the only writer to offer Martin’s books and the TV series based on them as an example of successful world-building. Many would say, to be sure, that the shadow of Tolkien’s and Jackson’s influence hovers over it, but perhaps that does not matter. It has brought respected long-form fantasy to TV, just as LOTR brought it to the big screen. It has gradually achieved critical acceptance, garnered a healthy number of awards, and contributed familiar tropes to modern culture, even for those unfamiliar with the books or series. I myself gave up on the novel after reading the first volume and have seen no episodes of the series. Already by the end of the first book it seemed to me that Martin was starting repeat his own devices, and if he was doing that within one book, what would later volumes be like? I certainly can’t see it as literature on a level even remotely approaching that of LOTR or even Harry Potter. I have not seen any episodes of the HBO series and hence cannot judge it. From what I can tell, it does not escape the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR, but that’s probably a matter of opinion.

Many fans who long to see an adaptation of Tolkien’s The Silmarillion have suggested that long-form television would be a more plausible medium than theatrical film. I consider The Silmarillion utterly unfilmable, except possibly in the hands of a brilliant animator, but that’s another issue. The point is that television, and especially powerful cable channels like HBO, are seen as the venue for long films that would be unlikely to be greenlit as high-budget theatrical features.

Despite appearances, I am not a keen fan of fantasy literature and films. The only fantasy novels (apart from children’s books) I have enjoyed enough to reread are LOTR, the Harry Potter series, and Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. The seven-part TV series based on the latter ended its American run on BBC 2 just over a year ago. I believe it is somewhat parallel to the LOTR film in being a reasonably successful–artistically at least–adaptation of a major work of literature It also bears no trace of Tolkien’s influence.

How does it escape? If you asked someone who had read both Martin’s books and Clarke’s whether they had read Tolkien, he or she would probably guess that Martin had and would have no idea whether or not Clarke had.

Martin admits his debt to Tolkien freely. “I revere Lord of the Rings, I reread it every few years, it had an enormous effect on me as a kid. In some sense, when I started this saga I was replying to Tolkien, but even more to his modern imitators.”

Clarke also was a Tolkien fan, but I have never seen anyone compare JS&MN to LOTR, either the original novel or the TV series. For one thing, she had other, quite different influences well, as described in a reader’s guide on her publisher’s website.

During an illness that required her to rest a great deal, Clarke re-read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and when she finished she decided to try writing a novel of magic and fantasy. She had long admired the fantasy writing of Ursula Le Guin and Alan Garner, but also loved the historical fiction of Rosemary Sutcliff and novels of Jane Austen. These various influences were to come together in a novel which is part magical fantasy, part scrupulously researched historical novel, with teasing faux-academic footnotes referencing a bibliography of magical books entirely of her own invention.

Clarke also has a literary skill that elevates her above most writers in the genre. Her approach was not to invent an imaginary world à la Middle-earth, but to begin by setting her story in the actual English history of the Regency era. Into that she inserted two magicians seeking to revive the tradition of Faerie-derived English magic and use it to aid their country during the wars with Napoleonic France. Her seamless blend of real historical figures and events with her own inventions can leave many nonspecialist readers wondering which is which.

I have already written about the TV adaptation of Clarke’s book, pointing out both what I consider some problems with the adaptation of the narrative and some real strengths of the series. As with LOTR, the adaptation’s strengths have much to do with the design, the special effects, and the acting. Indeed,the series won two BAFTA TV Craft awards, for production design (above, designer David Roger accepts his award) and special effects. In some ways, it could have been to TV what LOTR was to film, though it was far less successful with audiences and thus will no doubt have concomitantly less influence.

The elusive “masterpieces” of fantasy that Adcock suspects might escape from the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR could be either films or TV series. But unless the studios greenlight more imaginative fare, that shadow will persist for a long time.

On the point about whether Warner Bros. would greenlight a LOTR trio of films today. I discuss studio executives’ decisions about which fantasy films to make, specifically in relation to Warner Bros. and Jack the Giant Slayer, in “Jack and the Bean-counters.” In my 1999 book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood, I suggested that Hollywood’s originality and risk-taking had declined so much, even by then, that many classic and successful films could not be greenlit; I suggested Witness, Chinatown, The Fugitive, and Alien as fairly recent examples. By now the system has become even more exclusionary.

The idea that series TV offers the advantage of more time to play out the narrative of a long book is not true in all cases. Including credits, JS&MN runs a total of 406 minutes, while LOTR runs 558 minutes in its theatrical edition and an extra two hours in the extended home-video release. (In the 50th Anniversary edition, Tolkien’s novel runs 1029 pages without the appendices. The first edition of JS&MN is 782 pages.) Ironically, in the wake of LOT’s success, New Line optioned JS&MN as a possible successor to Jackson’s film. The Golden Compass took precedence, and eventually JS&MN became available for the BBC to adapt. Made as a trilogy, with a higher budget, it would have looked great on the big screen.

Wildstyle, Gandalf, and Batman in The Lego Movie (2014)

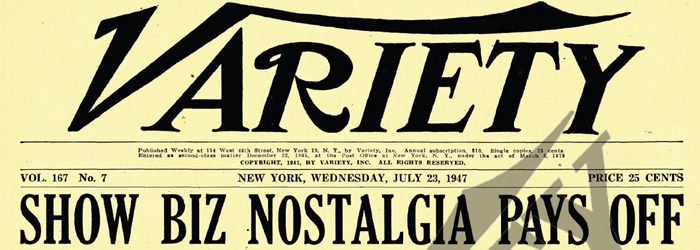

Born on the 23rd of July

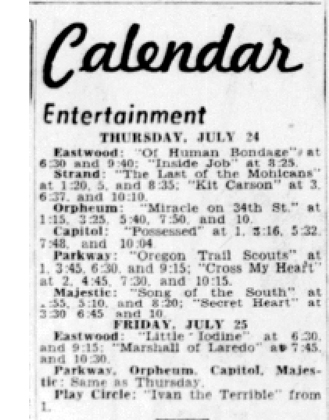

The Wisconsin State Journal, Wednesday 23 July 1947.

DB here:

Today I turn 69. (Please keep the cheers discreet.) I was born in western New York State, but I’ve spent over forty years in Madison, Wisconsin. So for fun I thought I’d take a look at what you could have seen on 23 July 1947 in my current home town.

This isn’t (just) an exercise in baby-boomer self-regard. Looking at the movie ads in the Wisconsin State Journal for that fateful day can remind us of interesting stuff about American cinema of the postwar years. Or so I think, fueled by work on Hollywood in the 40s for a book I’m nearly done with.

Classics, just passing through

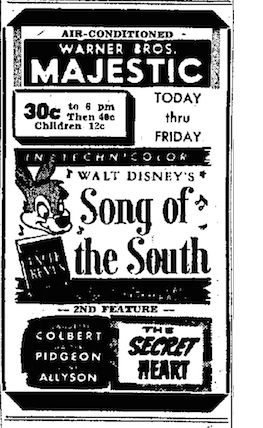

Song of the South (1946).

The first thing that strikes me the quality that’s on offer. On that Wednesday you could have seen four superb films (Rebecca, Stairway to Heaven, Song of the South, Possessed) and two worthwhile pictures (Of Human Bondage and Miracle on 34th Street). These movies are still remembered and admired.

Can this morning’s list of multiplex showtimes promise anything so enduring? Maybe Finding Dory and The BFG will be watched sixty-nine years from now, but our other current releases seem bound for oblivion. And of course the 1947 bill of fare was, with the important exception of Song of the South, designed for grownups.

Those who want to use this 1947 data-point as an example of the death of American cinema are welcome to do so.

Admittedly, today we don’t expect summer to generate the highest-quality films. (Though it often does; think of the last Mad Max installment. And James Schamus’s Indignation is coming up next week.) In 1947 the summer market was rather different from that today. Studios planned their major releases from late August onward, with big pictures playing through fall, winter, and early spring. June, July, and much of August were a slack stretch, when, Hollywood charmingly assumed, people wanted to be outside. So summer releases tended to be minor titles, and exhibitors turned to foreign fare, B pictures, and reissues.

Still, Possessed and Miracle were brand-new releases. At the end of the 40s, it seems clear, studios began releasing more of their important pictures in the summer. And as you can see, air conditioning–rare then, even in public buildings–lured some folks in.

In any case, for moviegoing purposes, I’d rather have been in Madison in July of 1947. In the two weeks sandwiching my birthday (16 July-30 July), I could have seen Brief Encounter, Her Sister’s Secret, Tomorrow Is Forever, Tender Comrade, The Sea Hawk, The Sea Wolf, Dead Reckoning, The Hucksters, The Unfaithful, The Lady in the Lake, Bohemian Girl, Boom Town, The Razor’s Edge, Love Laughs at Andy Hardy, Mr. District Attorney, Calcutta, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, Angel and the Badman, The Dark Mirror, Till the Clouds Roll By, Pursued, and Sister Kenny—along with a couple Lone Wolf and Falcon movies. Not a bad lineup. And I’m not counting La Grande Illusion and Ivan the Terrible on the UW campus.

Safety in numbers

Possessed (1947).

Then there’s quantity. Madison, Wisconsin had a population of about 65,000 in the year of my birth. It was dwarfed by Milwaukee, which had nearly ten times that. Yet by my count, over the two weeks around my birthday, a Madison moviegoer had 73 films to choose from. For the same 15-day stretch in town today, I come up with no more than 20. (For both time frames, I’m not counting campus or library screenings.)

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

Of course my 69-year-old self has a much bigger choice of movies than what’s in theatres. I can choose among thousands of titles on cable TV, disc, or streaming. TV wasn’t a significant part of the American landscape in 1947. Cinema existed in an economy of scarcity rather than overabundance.

This circumstance led people to go immediately to see the newest picture, as they couldn’t be sure it would return in second-run or a reissue. Today many of us skip a new release in theatres because we know we can catch it in a later video window. Does this all-you-can-eat plenitude make cinema seem less urgent and immediate—more a matter of “content” filling libraries and bookshelves and hard drives and Netflix queues? I think so. We’re all collectors now, in a way a 1947 moviegoer couldn’t be, but that means we lack the impulsion to see most films immediately. It takes effort to go out to see a film, but maybe that effort makes the experience more valuable (when the movie is satisfying, of course).

Dueling duals

Oregon Trail Scouts (1947).

The ads reveal more about quantity. You’ll have noticed that a great many of the films are playing on double bills (“duals”). From the 1930s on there was a perpetual debate about whether duals helped or hurt the industry. Most studio chiefs deplored them and confidently announced that a majority of audiences didn’t like them. The trade papers regularly ran stories predicting that the dual’s days were numbered.

They were wrong. Duals persisted into my college years; to see Help! (1965) twice in first release without buying another ticket, I had to sit through The Glory Guys (1965). Most exhibitors were independent of the studios, and they liked duals. So, obviously, did many viewers, who enjoyed getting two movies for the price of one.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

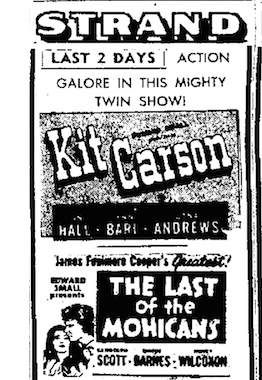

The other theatres in the ad are running duals. Some of them ran recent releases, but late in the run. For instance, the Parkway (despite its name, another downtown theatre) was a big venue, with a 1200-seat capacity. On my birthday it screened Cross My Heart (a January ’47 release) and Oregon Trail Scouts (a May release). These were first-run, but with less must-see appeal than Miracle and Possessed. Also, Oregon Trail Scouts is a prototypical B picture, running 58 minutes. So the Parkway, another Fox-controlled screen, mated a mildly attractive Paramount programmer or “nervous A” with a Republic B. A third Fox venue, the Strand, a 1300-seater on the square, drew on second-run titles and reissues for its duals.

The town’s smaller theatres relied on duals. The Majestic, an old vaudeville house with some of the most skewed sightlines in Christendom, was at that point another Warners house. Yet it had no qualms about showing subsequent-run titles from Disney/RKO (Song of the South, in its third Madison run) and MGM (The Secret Heart, back for a second).

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

As a result, in my one-day snapshot every major Hollywood studio is represented; even RKO gets in with its “Passport to Nowhere” short. How can this be, in a town with four Fox screens, two Warners screens, and only one independent exhibitor? Research by our colleague Andrea Comiskey has shown a remarkable flexibility in studio screening policies. Often a subsequent-run house owned by a studio played few or none of the studio’s own releases. This way everybody could make money off everybody else’s movies. Such are the ways of oligopolies.

Why so many B’s, particularly Westerns? Given double bills, they were what the trade papers openly called fodder, and they saved money. B’s were rented on a flat-fee basis, while A’s were rented on a percentage basis. Some exhibitors ran the B more frequently than the A each day, so as to keep more of the box-office take. Such wasn’t the case with the Madison, though: Both Stairway and Vigilante played an equal number of times each day.

Was the B the chaser, clearing the house after the A? Maybe, but maybe someone coming to see a prestigious Powell and Pressburger would stick around for Jon Hall and Andy Devine. In any case, since the Big Five studios were making fewer pictures in the 1940s and were concentrating on A items (the big-ticket income), the ongoing demand for duals helped less important studios, which were heavy suppliers of B’s.

There was only one independent house in Madison proper. The Eastwood (still standing, now a live venue and called the Barrymore) was playing second-runs in its 950-seat auditorium.

Finally, runs were tied to ticket price. I haven’t got good information on ticket costs in these theatres, but the fact that the Majestic boasts of charging $.30 until 6 PM, and then bumps the cost to $.40, is typical of a second-run house of the time. First-run tickets, depending on time of day, could be $.50 or more.

Those costs, by the way, translate to ticket prices between $3.30 and $5.50 in today’s currency. Another data point favoring the good old days.

Heavy rotation

The Middleton Theatre, Middleton Wisconsin, in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

Duals multiplied the number of pictures on offer. So did the length, or rather the brevity, of runs.

The first-run A’s, Possessed and Miracle on 34th Street, ran a week; Miracle, in fact, was moved over to the Madison at the end of July for a longer stay. But most duals changed more frequently. The Madison’s dual of Tomorrow Is Forever and Tender Comrade ran five days, as did the Strand’s Last of the Mohicans and Kit Carson. But the Parkway typically changed bills every three days, while other theatres split up the week even more. Some programs ran only two days.

We’re so used to pictures hanging on for weeks or months that these rapid playoffs are surprising. But here my birthday snapshot is a bit misleading. Many of the films brought in for two or three days were second-run titles, and a surprising number were reissues.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

The number of reissues increased powerfully just before my birthday. In late May, the Hollywood Reporter claimed that of 224 pictures playing in metropolitan New York, 105 were “oldies.” Just after said birthday, HR reported that “the highly satisfactory boxoffice results from reissues in recent months, plus the necessity of averaging down the cost of new productions which continue to call for multi-million dollar budgets, will result in nearly twice as many reissues in 1947-48 as in the past year.” That number was said to be 75 from the Majors, along with another 100 or so titles already sold or leased by non-Majors.

The oldest reissue on offer in Mad City on my birthday was The Last of the Mohicans (1936), paired with Kit Carson (1940). This package had already had great success in New York and had helped sustain the reissue boom. So strong was this Mighty Twin Show that producer Edward S. Small could demand not the usual flat-rate terms but rather a 35% of the box office. In Madison during the weeks around 23 July, you could have seen a great many other films from the 1930s and 1940s, on brief-stay duals.

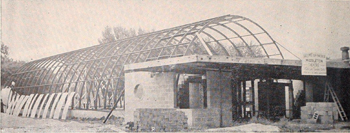

Speaking of reissues, the Middleton, the venue announcing Rebecca in the ad, is interesting in its own right. Middleton is a pretty bedroom community west of Madison, then with about 2000 souls. Now, thanks to infill, it’s more or less a continuation of our town. Its theatre, an independent house built in 1946 and with a capacity of 500, ran both second-run and reissues, including, during the DB magic weeks, Sun Valley Serenade (1941), The Westerner (1940), and, for one day, Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942).

Maybe more interesting is that the Middleton was a Quonset hut, with a wraparound roof.

More about the Middleton here. Kristin and I saw E. T. there, and I wish we’d gone more often. It was demolished in 1992.

Foreign accents

A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven, 1946).

The presence of Stairway to Heaven (in first run) points up another trend. During the 1940s, foreign films gained a new prominence on American screens. While reissues were flooding New York City screens as noted, the number of imports among them was sharply up: fourteen British titles, five French, four Spanish, three Italian, two Russian, and one Swedish.

Those proportions reflect the growing popularity of British cinema. At year’s end, Variety noted that the number of British releases in 1947 doubled from the previous year, from ten to twenty. In the two weeks surrounding my birthday, Madisonians could have seen Brief Encounter, also at the Madison. The Madison seems to have sometimes operated as an art house. It screened Open City a month earlier, promoted in a memorable ad that somehow plays up sexytime without showing Anna Magnani.

Note what’s playing with it. The Madison stayed classy.

1946 was the high-water mark of American movie attendance and Hollywood studio profits. 4.7 billion US tickets were sold, and profits came to nearly $120 million. Attendance remained strong in 1947, but profits started to fall steeply, to about $87 million. The soaring costs of production, including millions spent on rights to projects that were never filmed, came due. And soon enough attendance dropped calamitously as well. Ticket sales in 1952 were only a bit more than half of 1946’s total. A great many Americans stopped going to the movies.

There were rumblings, though, before I showed up. “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” announced the headline of Hollywood Reporter for 20 May 1947. Was this just a “spring slump,” such as those before World War II, when good weather drove people outside? “If there is no general rise in grosses by the middle of July,” said one executive, “then our fears will have been realized, as it will reflect an economic crisis.” Studio employment was off 20%; the Majors’ building plans were put on hold; and reissues from non-Major sources were gaining a bigger share of the receipts. Ultimately, 1947 fell off only a little, but film folk were nervous. The big dip would come soon.

Another crisis: In less than a year after my birthday the Supreme Court would declare that the studios’ ownership of theatres was monopolistic, and the companies would begin gradually splitting off their theatre chains.

I was born, then, on a sort of cusp. By the time I was 5, people were declaring the studio system dead. Knowing nothing of this, I continued watching new releases (Peter Pan, Francis the Talking Mule movies) and old films that were starting to show up on TV. I didn’t suspect that, decades along, I would spend my more-or-less adult life studying those movies that played the Capitol, the Parkway, and the Middleton. Just looking at this page from the State Journal has me hoping that Kristin gets me a time machine for my next birthday.

For help in preparing this entry, thanks to Lea Jacobs, Jeff Smith, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Lisa Marine, and Rob Thomas.

Some sources: “Double-Bill Reissue Packages Prove Surprising B.O. on B’way,” Variety (9 April 1947), 7, 18; “Re-Issues Flood New York Screens,” Hollywood Reporter (22 May 1947), 1, 3; “Reissues Doubled for 1947-48,” HR (26 August 1947), 1, 11;”Industry Schedules 130 Re-Releases for This Year,” HR (5 February 1948), 1, 13; “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” HR (20 May 1947), 1, 12; “Industry in Crucial Period before Upturn, Say Toppers,” HR (26 May 1947), 1, 12; “July Will Disclose Actual Extent of Boxoffice Downturn,” HR (9 June 1947), 10; “8 Majors and 4 Lesser Distribs Released 428 in ’47 vs. 405 in ’46,” Variety (31 December 1947), 6. Chapter 6 of Susan Ohmer’s book George Gallup in Hollywood (Columbia University Press, 2006) provides an excellent overview of the disputes about double bills.

There was another crisis in my late prenatal phase. In response to shopkeepers, the ever-watchful Wisconsin state legislature had drafted a bill banning candy, food, and drink from being sold in movie houses. Exhibitors mobilized and lobbied for tasty snack treats. “With boxoffice grosses rapidly slipping from their wartime peaks to pre-war levels, the candy, popcorn, sandwich and soft drink sales now are especially essential to keep the houses on the profit side of the ledger.” “Wisconsin Candy Sale Ban Doomed,” HR (7 May 1947), 5. Fortunately for all Cheeseheads, this bill was defeated.

Browsing the wonderful site Cinema Treasures can make you aware of all those lost movie houses. The Wisconsin Historical Society presents many photos of Madison’s old theatres. My photo of the Middleton in the 70s comes from this collection, Reference no. 5572.

The saga of Madison’s Orpheum is told in part here, though an update on all the intrigue is probably in order. At least the magnificent sign has been redone and has gone up. The Capital Times covers the process here and here. The refurbished sign got lit up last night. For more on local theatres, including the ones I actually frequented back East, go here and here. Also relevant is this visit to Rochester’s Cinema Theatre, with information from Andrea Comiskey. Also a cat.

On the importing of movies from overseas at this period, the definitive source is Tino Balio’s book The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2010).

P.S. 30 July 2016: The Middleton Theatre stirs fond memories. See Nadine Goff’s Facebook page on historic Wisconsin photographs for reminiscences of sticky floors and rain on the roof.

Another fateful birthday headline.