Archive for 2016

Hail, again, to the King

A Touch of Zen (1970).

DB here:

Criterion has just put out its DVD/Blu-ray of King Hu’s A Touch of Zen. I wrote liner notes for it, which are available on the Criterion site. I haven’t gotten my copy of the edition yet, but the reviews I’ve seen are praising Tony Rayns’ interview (no surprise) and the other features.

For more on one of my favorite cuts in A Touch of Zen, you can visit this blog entry (complete with splice marks). There’s also a discussion of the goldenrod combat here. In Poetics of Cinema, there’s a longer essay called “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” and a chapter of Planet Hong Kong is devoted to comparing his work to Chang Cheh’s and Lau Kar-leung’s.

With A Brighter Summer Day, this is another Criterion triumph and a must for every cinephile. And why am I never around when a swordswoman flies by?

Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly

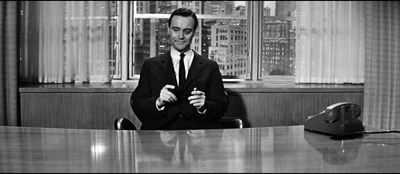

The Apartment (1960).

DB here:

Rory Kelly, whom I met some years ago at a conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, has been a pioneer in linking the practices of film production to larger issues of narrative, performance, and artistic form. What follows is a version of a superb paper he gave at the Society’s annual meeting in Ithaca in June. Since Kristin and I are always eager to know how practitioners think of their craft, we jumped at the chance to pass along his thoughts in one of our guest blog entries.

Rory comes fully prepared to the task. Currently an Assistant Professor in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, he has been a bright light in filmmaking for many years. His first feature, Sleep with Me (1994) premiered as an Official Selection at Cannes and was released by MGM/UA. His second feature, Some Girl (1998), garnered him the DGA-sponsored Best Director Award at the Los Angeles Film Festival, and his 2006 short, The Women, premiered at the Long Island Film Festival. He was also co-executive producer of mtvU’s Sucks Less with Kevin Smith. Rory has been a Film Independent Screenwriting Fellow and is currently working on several research projects, including studies of discourse analysis and emotional expression in film. At the same time, thanks to a 2016-2017 Heillman Fellowship, he is preparing a feature documentary about racism in America, To Someday Understand.

Here’s Rory on a perennial problem of the screenwriter: the character arc.

Since the 1960s, the character arc has become all but obligatory in Hollywood movies. Genres like sci-fi and horror, once largely unconcerned with character change, now often include it. Compare, for example, the 1953 version of War of the Worlds with Steven Spielberg’s 2005 remake. In the latter the alien invaders are not only defeated, but in the process Tom Cruise’s character, Ray Ferrier, becomes a better father.

Why has character change become so prominent? In The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006), David offered some suggestions. The psychological probing in plays by Arthur Miller, Paddy Chayefsky, and Tennessee Williams became popular models of serious drama. Teachers and writers were persuaded by Lajos Egri’s book, The Art of Dramatic Writing (1946), in which the author advises that characters should grow over the course of a play. There was also the impact of self-actualization movements of the 1960s and 1970s that held out the promise of personal growth and transformation.

It’s also likely that star power has had considerable influence. When trying to raise financing for a low-budget indie script a few years back, my collaborator and I were advised by three different seasoned producers to give our protagonist a more pronounced arc or we would never be able to attract a name actress to the role. Whether they were right or not, I do not know, but their shared assumption about attracting talent is telling.

Given how common the character arc has become, we need to better understand how it is typically handled. I think we can identify and analyze six narrative strategies that create a particular character type: the protagonist who is flawed but is capable of positive psychological change. My primary example will be The Apartment (1960).

I’ll also consider aspects of character change in Casablanca (1942), Jaws (1975), and About a Boy (2002). This list will allow me to consider the character arc over six decades, from the studio era to contemporary Hollywood, and across several genres. Limited as it is, this set of films suggests that certain techniques of character change recur again and again. In tracing them, I’ll occasionally make reference to the four-part plot pattern Kristin has set out in Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) and several entries on this site: the Setup, the Complicating Action, the Development, and the Climax.

A six-step program

Casablanca (1942).

First, a filmmaker seeking to construct a character arc will almost inevitably begin by establishing that his or her protagonist is of (1) Two Minds. I mean by this that the character has competing impulses. Think of Rick in Casablanca. On the one hand he is inclined towards communal action; on the other hand he sticks his neck out for no one. This latter behavior is solidified during the Setup portion when he assists in Ugarte’s arrest.

It can be termed Rick’s (2) Negative Behavior Pattern. It is a pattern because it is a type of behavior Rick enacts again and again, as when he repeatedly refuses to give the letters of transit to Victor and Ilsa. The film even turns Rick’s selfishness into a motif.

Still, Rick retains an impulse towards virtuous behavior, his (3) Positive Behavior Pattern. During the Setup, for example, he does not allow a notorious Nazi to gamble in his café. Later he helps a destitute young couple earn passage to America by allowing them to win at roulette.

The film as well makes a motif of Rick’s virtuous side.

The ongoing interaction of these two behavior patterns allows the filmmakers to maintain audience sympathy for Rick, to motivate his final change of heart—if Rick were not of two minds, his final transformation would come out of nowhere—and to delay that change of heart long enough to create expectations and suspense.

What often postpones a protagonist’s change of heart is a (4) False Belief. In many films a misunderstanding is introduced that motivates the protagonist’s negative behavior pattern. Because of this the character need only discover the truth in order to be reborn. Think again of Rick. It is because he falsely believes that Ilsa once jilted him, leaving him alone in the rain at a train station in Paris, that he has become a sullen saloonkeeper who sticks his neck out for no one.

But once Rick learns the truth—that Ilsa left him because she discovered her husband was alive—Rick forgives her. He then devises a scheme to help her and Victor escape, and he makes plans to join the Resistance. The truth, in short, sets Rick free and quickly and efficiently allows for his change of heart.

Another way to look at Rick’s transformation is that his false belief about Ilsa has made him essentially a nihilist who believes that there is nothing worth living for. When Victor says, “If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die,” Rick replies, “What of it? Then it’ll be out of its misery.” Seen from this angle, when Ilsa finally convinces Rick of the truth, we are meant to infer that his change of heart is the result of a realization that love and loyalty still exist in the world.

The final two strategies I want to discuss concern the story world. In the case of flawed protagonists the rules and values of the fictional world may be established as conflicted in a way that matches the protagonist’s competing impulses. On the one hand there is what I term the (5) Normal World. This constitutes the dominant rules and values in play as the movie begins. Against this there is what I term the (6) Possible World. This constitutes what the normal world should be.

Think once more of Casablanca. That city is established as a place where a great many people have abandoned their better impulses and are out only for themselves. The primary representative of this worldview is the charming but corrupt Captain Renault. However, the story world also includes Victor and other members of the Resistance, and they are believers in a new world; one based upon a common cause. So the story world is, like Rick, flawed but of two minds.

Rick occupies a psychological space between Renault and Victor. In the end, by siding with Victor, Rick not only abandons his negative behavior pattern, he also begins the process of overturning the rules of the normal world. The change is suggested by Renault’s becoming, as it were, Rick’s first convert. They leave together to join up with a mysterious free French garrison at Brazzaville.

Rick’s character arc is not an isolated device but a central organizing principle of the plot. The same process is at work in The Apartment.

The Apartment: A normal world?

The Apartment tells the story of an ordinary accountant, C. C. Baxter, played by Jack Lemmon. In a calculated attempt to gain a promotion, Baxter allows his bosses to use his apartment for their extramarital affairs. Baxter is also smitten with an “elevator girl,” Fran Kubelik, played by Shirley MacLaine. But unbeknownst to Baxter, at least during the first half of the film, Fran is having an affair with the big boss, Mr. Sheldrake, played by Fred McMurray. Sheldrake is only stringing Fran along, though, and because of his treatment of her she eventually attempts suicide. Baxter finds her just in time and with the help of his neighbor, Dr. Dreyfuss, saves Fran’s life.

Baxter becomes Fran’s caregiver, but also Mr. Sheldrake’s protector, ensuring that news of Fran’s suicide attempt does not leak out. In the end, however, Baxter learns the error of his ways and finally follows the advice he is given by Dr. Dreyfuss.

When Baxter does become a mensch, he succeeds in winning Fran’s heart.

The six-step strategy displayed in Casablanca is launched in the opening few minutes of The Apartment.

We learn a great deal from this opening sequence. We learn that Baxter has a problem with his apartment and we learn that Mr. Kirkeby, the boss using his apartment, doesn’t respect him. The boss’s disdain helps garner sympathy for Baxter. Yes, Baxter is ill-advisedly allowing his bosses to use his apartment, but his bosses take advantage of the situation and mistreat him.

So why does Baxter let his bosses push him around? He wants a promotion, but why must he be so obsequious to get it? Is he unworthy? No. As we see right away, he is a hard worker.

In the opening voiceover we learn that Baxter is smart, or at least good with numbers, that he is enthusiastic about his work as an accountant, and that he respects and is impressed with the company he works for. He is a diligent company man, both capable and earnest. So why is he such a pushover?

To answer that question we need to look at the normal world. The film almost immediately introduces us to Consolidated Life, the insurance company Baxter works for. It is a beehive, an impersonal and monotonous corporate colony. And Baxter is depicted as an anonymous drone: he works on the 19th floor, Section W, at desk #861.

Baxter is not just a cog in a machine; he also behaves like a machine when we see his head bob up and down in unison with his calculator. If at the end of the film Baxter becomes a mensch, a human being, then at the beginning of the film he is an automaton. He does what he is told. That is part of being a company man.

Fran, who functions as co-protagonist, works inside a machine. Her gray uniform blends into her surroundings.

Fran and Baxter are insignificant, powerless and anonymous people lost among the 8,042,783 New Yorkers. In The Apartment status, power, money and the freedom to do what you want, other people be damned, are the highest values people can aspire to. And those without status, power and money are nobodies. That is how the normal world works in The Apartment.

The only way to escape anonymity and insignificance is to climb the ladder of corporate and/or social success, and presumably become one of the exploiters. This is exactly what Baxter and Fran try to do. Baxter, after all, wants to be a big boss like the men he lets use his apartment. His gamesmanship eventually allows him to jump the promotion line. His co-worker has been at Consolidated Life twice as long as Baxter, but because he does not play the game, he is not promoted.

Fran wants a promotion too: from mistress to wife of a very powerful man. She becomes to some degree complicit with Sheldrake in disregarding the needs of his wife.

Both Baxter and Fran, then, are willing to climb over other people to get what they want. Still, they aren’t vicious. In most ways, Fran is a kind and encouraging person. When Baxter comes up for his first promotion she tells him, “It couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.” And Fran actually loves Sheldrake. Fran is not Sylvia, a woman we meet in the opening sequence, who seems mostly interested in having a good time.

Just as Fran is not like Sylvia, Baxter is not like his bosses. For one thing, he apologizes to his neighbors for all the noise his bosses make during their trysts. He even tries to correct the situation. And unlike Sheldrake and Kirkeby, Baxter does not want to simply seduce Fran.

Baxter is naïve, a romantic, a rank sentimentalist. And his chances for success in this world, like Fran’s, are limited.

In sum, Baxter and Fran are of two minds. They exhibit both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern. This is very important. Because they both basically have good intentions—or aren’t cynical enough for the world they inhabit—they can grow as characters.

But given their good intentions, why do Fran and Baxter have negative behavior patterns? The answer is that each harbors a false belief (related to the normal world) that motivates their negative behavior pattern. Fran’s false belief is that Sheldrake loves her. And because of this she continually trusts him. Here she is going off in a cab to sleep with him, even though we know that Sheldrake hardly cares about her.

In parallel fashion, Baxter believes that corporate success will bring him happiness, but in the end it doesn’t. He gets his big fat promotion with his own office, and he’s miserable.

Still, as long as Baxter harbors the illusion that climbing the corporate ladder will make him happy, he is willing to kiss up to his bosses and allow them to push him around as a way to get ahead. That is Baxter’s negative behavior pattern: he is a toady.

The Apartment: Delay and the darkest moment

Sustaining a character’s positive and negative behavior patterns often becomes of central importance in a film’s second half, when what Kristin calls the Development is launched. In some films the protagonist actually has enough information by this point to reconsider the false belief, but that doesn’t happen. The protagonist clings to error.

The midpoint of The Apartment is the moment roughly an hour into the film when Baxter discovers Fran comatose in his bed. As Kristin points out, a midpoint typically recasts character goals, and Baxter gains a new purpose: saving Fran.

Baxter is worried that Fran will try again to kill herself, so a lot of the Development focuses on his attempts to keep her safe. But Baxter is also protecting Sheldrake during this section of the film. He induces the doctor not to report Fran’s suicide attempt to the police, and he hides Fran in his apartment until she’s better. Baxter’s competing motives, in other words, remain in play. Helping to save Fran’s life, and learning that there is a terrible cost to Sheldrake’s callous behavior should be enough to motivate Baxter to turn against Sheldrake. But he remains on the job.

We see something similar happen about twenty minutes into the Development, when Baxter phones Sheldrake to tell him about the suicide attempt. Sheldrake won’t even come to visit Fran. Baxter is confused and disappointed by this response, but he nonetheless promises his continued support.

This is a common strategy during a Development section. The flawed protagonist is one or more times brought to the brink of character change, but he or she pulls back, clinging to the negative behavior pattern. We see exactly this withdrawal in Casablanca. At the midpoint in that film Ilsa visits Rick and tries to tell him about her relationship with Victor. Rick has an opportunity here to accept the truth, which would set him free, but he rejects it. He clings to his false belief that Ilsa betrayed him and Paris.

Rick is given a second chance roughly halfway through the development when he allows the young couple to win at roulette. Rick’s employee, Karl, is watching from the sidelines, and he is thrilled. He believes that Rick is turning over a new leaf, and so do we. But immediately following this event Victor directly asks Rick for the letters of transit, and Rick bitterly says no.

These are of course delaying tactics, and ones we should expect. Kristin points out that the Development section usually contains numerous delays that create rising tension and suspense, while forestalling resolution.

In The Apartment‘s Development section, certainly Fran’s change of heart is delayed. Despite being driven to attempt suicide by Sheldrake’s treatment of her, she nonetheless announces the next day that she’s still in love with him. She even reaffirms her false belief.

Fran’s near-death experience should be enough to convince her that she needs to end her relationship with Sheldrake, but she too clings to her false belief and negative behavior pattern. Still, in spite of all this, it would be a mistake to say that no progress is being made. Baxter after all is horrified by what Fran has done to herself and Fran is beginning to entertain doubts. She says that “maybe” Sheldrake loves her. And all of this culminates in a moment of self-knowledge:

They are, in short, changing. Also, the possibility of a romantic relationship is finally introduced when Baxter and Fran prepare to sit down to a candlelit dinner together.

With these new story premises in place, the stage is set for Baxter and Fran’s final changes of heart in the climax. But not before a few more delaying tactics are deployed.

First, Fran’s brother-in-law Karl arrives and breaks up Fran and Baxter’s dinner plans. Then Baxter visits Sheldrake to tell him that he is in love with Fran and intends to marry her. But Sheldrake beats him to the punch. His wife has found out about his philandering and kicked him out of the house. Now Sheldrake plans to marry Fran. But to thank Baxter for taking care of business, Sheldrake gives him his big promotion.

As we’ve seen, corporate success is no longer what Baxter wants. In current screenwriter parlance, this is his darkest moment. It’s immediately followed by this exchange:

Fran is clearly ambivalent about her impending marriage to Sheldrake, and Baxter is clearly acting out, trying to hurt Fran. Also, Fran is deeply disturbed to see the cynical side of Baxter out in full force. And this brings me finally to the possible world. As we also saw in Casablanca, the story world in The Apartment is divided, and again the question is who will the protagonist become. Will Baxter grow up to be Dr. Dreyfuss, who represents a communal worldview, or will he grow up to be Mr. Sheldrake, who represents a selfish worldview?

Now it seems that Baxter has become Sheldrake–except we don’t, or aren’t supposed to, believe him. The real point of the exchange between Baxter and Fran is that Baxter no longer holds his false belief. He is using it now only as a defense mechanism, as a cudgel to punish the woman he sees as having betrayed him. He is, in short, pretending. And since he is no longer committed to his false belief he can change.

As has become typical in Hollywood films, the protagonist’s darkest moment leads to enlightenment. In the very next scene Sheldrake asks Baxter for the key to his apartment so that he can bring Fran there for New Year’s Eve, and Baxter says no. When Sheldrake threatens to fire him, Baxter angrily throws a key onto Sheldrake’s desk, and the quiet confrontation ensues.

Baxter thought that the way the stand out was to play along, but in the end he discovers that the way to stand out is to stand alone and cease to be a collaborator. Also, Baxter’s transformation, like Rick’s in Casablanca, inspires a conversion in another character, Fran, and in this way it suggests an overturning of the rules of the normal world. As we’ve already seen, Fran is ambivalent about her new relationship with Sheldrake. And when Sheldrake at a New Year’s Eve party tells Fran that Baxter quit and wouldn’t give him the key, she smiles mysteriously as if finally seeing the light.

She realizes it is Baxter who loves her and not Sheldrake. So she abandons her false belief and the negative behavior pattern it engenders. She leaves Sheldrake and rushes to meet Baxter. And that’s the end of the story.

Two men of two minds

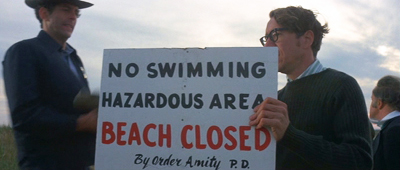

Finally, how enduring are these character-arc patterns? Consider, briefly, Jaws and About a Boy.

Chief Brody is a former New York City police office who has become sheriff of a small island community, Amity. Why did he leave the city? Because, as he explains, crime in New York is out of control and he couldn’t do anything to change that. So he has come to Amity, a world in which, he thinks, one person can make a difference.

Yet for this cop, living in Amity is a cop-out. There hasn’t been a murder there for thirty years. It is a town where one person doesn’t have to make a difference. Yet when the shark arrives, Brody discovers that Amity is the same as New York City. He wants to close the beaches, but the city officials won’t let him. He crumbles under their pressure. Brody is as powerless to make a difference in Amity as he was in New York.

That is how the normal world works in Jaws, and Brody, like Baxter, initially conforms to it. At the beginning of his story he’s defeatist. He always backs down in the face of conflict. He is not confident. Later, on Quint’s boat he wants to turn back. He’s always feeling overwhelmed, a state expressed in his fear of drowning. So Brody goes along to get along.

Accepting his powerlessness is Brody’s negative behavior pattern. But like Baxter and Rick, he can’t help caring. He works to close the beaches, if only for a day, and after a young boy gets killed, he accepts the blame.

Brody exhibits the typical split between positive and negative behavior. Yet because he’s of two minds, he can change. In a crucial turning point, he vows to join Quint and Hooper in hunting the shark. At the climax, he doesn’t back down. He is fearless and he does make a difference. He helps save the town, and in the process he gets over his fear of drowning.

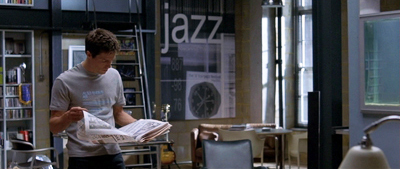

About a Boy, a British-American-French coproduction, released domestically by Universal Pictures, suggests that the techniques I’ve been considering have some cross-border appeal. A 38-year old man-boy, Will Freeman, played by Hugh Grant, lives in luxurious isolation off the royalties from a popular Christmas song his father composed decades before.

Neatly reversing John Donne’s dictum, Will asserts in the opening moments that “all men are islands.” In accordance with this philosophy he has built for himself “a little island paradise,” a swanky apartment filled with cool consumer goods like a chrome-plated espresso maker, a sleek TV, and a vast CD collection. But then Will meets and ultimately befriends Marcus (Nicholas Hoult), a 12-year old misfit with a suicidal mother, who lives his own willed exile because of not being accepted at school.

The story deals with how Will and Marcus and Marcus’s mother Fiona (Toni Collette) become integrated into the world.

Will and Marcus are co-protagonists, but Will’s character arc is more pronounced. Will’s false belief, of course, is that he can make it alone. The problem, though, is that solitude leaves his life devoid of meaning. He has no job and he sleeps with many women but doesn’t date any of them, at least not for very long. As he several times states, “I don’t do anything,” or more to the point, “I do nothing.” Will, however, sees this lack of meaning as a positive: “Me? I didn’t mean anything, about anything, to anyone, and I knew that that guaranteed me a long, depression-free life.”

Will’s false belief is not simply that he thinks he can make it on his own; he believes he can avoid misery by avoiding commitments. This is most apparent when Marcus’s mother attempts suicide.

While Will helps out by driving Marcus to the hospital, the sequence ends with a grim bit of voiceover as we see Will drive off alone into the night.

The thing is, a person’s life is like a TV show. I was the star of the Will show, and the Will show wasn’t an ensemble drama. Guests came and went, but I was the regular. It came down to me and me alone. If Marcus’s mom couldn’t manage her own show, if her ratings were falling, it was sad, but that was her problem.

Will, however, is of two minds, a state the film expresses in a number ways. First, despite being a committed loner, he very early in the plot begins dating a single mother. As we see him gleefully playing with this woman’s young son, he says in voiceover: “And for the next few weeks I was suddenly Will the good guy.”

When Will decides to break up with this woman, in part because she made him late to an IMAX movie, he adds, “I was going to have to end it, but having been Will the good guy I did not relish going back to my usual role of Will the unreliable, emotionally stunted asshole.” He is, apparently, self-aware, and his use of the word “role” seems intentional, suggesting as it does that Will the Asshole is a persona he adopts to avoid complications. We also learn that in the past Will volunteered at a soup kitchen, though he admits he never made it there to help out. And we discover that for a time he worked the phones at Amnesty International, but seems to have mostly used this as an opportunity to pick up women on his call lists.

The point the filmmakers are comically making is that Will has good impulses, but is unable to sustain them in the long term. He has both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern, the latter very clearly motivated by his false belief.

The normal world is established as one in which people are abandoned. The film is full of single moms, including Marcus’s mother, and Will tries to abandon everyone he meets. In the opening scene he throws away the phone number of a woman he has slept with, even as she is leaving an inviting message on his answering machine.

Most significantly, Fiona almost abandons Marcus when she attempts suicide. In the wake of this, Marcus is worried that his mother will try again, and that she may succeed when he’s not there. He gets an idea: “Suddenly I realized that two weren’t enough. You needed backup.” With this realization Marcus defines the possible world for us. It is one that is comprised of teamwork and mutual support. In search of this new world, Marcus attempts to fix up Will with his mother. His goal is to get Will to marry her so that they can both look after her.

The dreamed-of marriage never occurs, but Marcus and Will slowly become friends, spending most afternoons together watching TV and sometimes talking. Will helps Marcus become more cool, which allows him to begin making friends at school.

Because of his growing friendship with Marcus, Will comes to realize that misery stems from loneliness, not commitment. He abandons his false belief and the negative behavior pattern it motivates. Not only does he fall in love, but for Marcus’s sake he also offers his friendship and emotional support to Fiona to help prevent her from attempting suicide again. In this way he demonstrates that he has learned the necessity of real, meaningful relationships. The film ends with all the main characters together in Will’s apartment–once his desert island paradise–sharing Christmas lunch. There is even a hint that Fiona too will find love. This ending marks a clear overturning of the rules of the normal world.

Two Minds, Positive and Negative Behaviors, False Belief, Normal vs. Possible Worlds: Maybe all character arcs don’t follow these principles. We’ll have to test them against many more movies. At least, though, they seem to offer widespread, enduring strategies for constructing character change.

In every case I’ve considered, the protagonist discovers his or her “true” self, the good or well-adjusted person that has been lurking within all along. Which suggests that radical, 180-degreee character change is rare–most likely because it is difficult to motivate. Arguably, though, Breaking Bad pulled off a version of it. And speaking of Walter White, it remains to be studied how character change is typically handled in long-form television, which is becoming an ever more significant mode of Hollywood storytelling.

For more on principles of Hollywood plotting, see the entry “Open Secrets of Classical Storytelling,” “Understanding Film Narrative: The Trailer,” and “Time Goes by Turns.” Some ideas about character change are set out in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” There’s a bit on The Apartment as a 1960 film here.

About a Boy (2002).

Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net

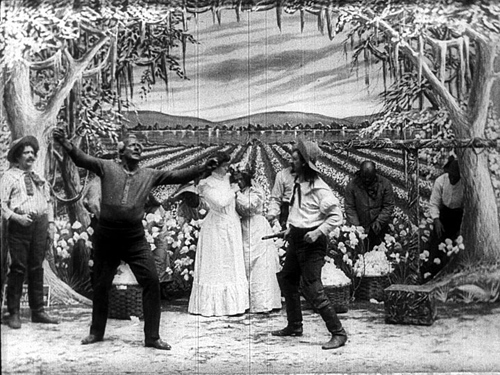

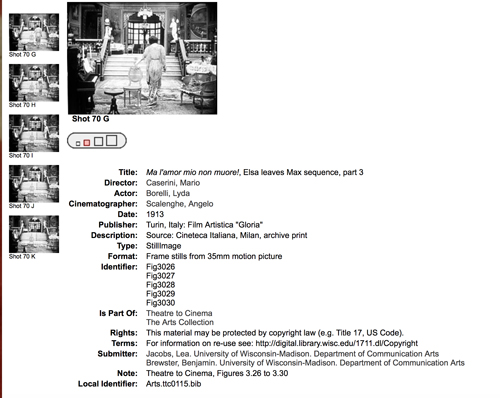

Ma l’amor mio non muore! (aka Love Everlasting, 1913). Lyda Borelli.

DB here:

The core of cinematic expression is editing. Since the 1920s, that view has been part of the lore of film aesthetics. Editing, people said, is what distinguishes film from other media. After all, the single shot is both a picture (like a painting) and a dramatization (like a scene in a stage play). But put one shot with another and you’ve got a technique impossible to parallel in other media.

But if we look closely, we find that the film image is as “uniquely cinematic” as editing. After all, a film is an image, but it’s a moving image, which is sharply different from a painting. And although a shot is a dramatization, it’s two-dimensional (unlike a stage scene) and the space it captures is quite different from that of the theatre. Anyhow, maybe editing isn’t uniquely cinematic. Comic strips juxtapose discrete images, and some forms of theatre (such as pageants, or turntable stages) can shift rapidly between scenes. Once we start to compare adjacent media, we find many overlaps in their expressive resources.

Why did early film theorists make editing so important? They were often defending the view that film was a new art, in the teeth of opponents who claimed that it was simply photographed theatre. Accordingly, film’s defenders looked for features of films that seemed to have no counterpart in theatre, such as the close-up and, more pervasively, editing.

Since then, we’ve come a long way in our understanding of film’s artistic capabilities. Filmmakers, particularly those in the early sound era (Renoir, Ophuls, Dreyer, Mizoguchi), showed the expressive power of the single shot. This tendency was amplified in the 1950s and 1960s with Antonioni, Jancso, Andy Warhol, and many other directors. Now nobody blinks if a filmmaker like Hou or Yang presents a lengthy, unedited sequence.

Informed by what’s possible in the single shot, we ought to find the earliest filmmakers using the resources of staging, composition, and performance in felicitous ways. So we do. Once we foreswear the cult of the cut, we can see that early cinema made extensive use of cinematography and mise-en-scene for powerful artistic effects. And conceding that, we suddenly find ourselves back in the lap of the other arts–painting and theatre.

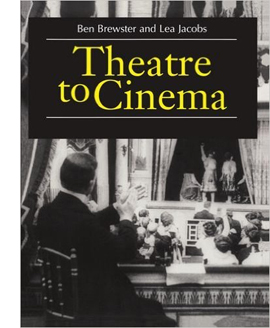

Living pictures

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

Here’s the authors’ statement of the book’s argument:

While previous accounts of the relationship between cinema and theatre have tended to assume that early filmmakers had to break away from the stage in order to establish a specific aesthetic for the new medium, Theatre to Cinema argues that the cinema turned to the pictorial, spectacular tradition of the theatre in the 1910s to establish a model for feature filmmaking. The book traces this influence in the adaptation and transformation of the theatrical tableau, acting styles, and staging techniques, examining such films as Caserini’s Ma ľamor mio non muore!, Tourneur’s Alias Jimmy Valentine and The Whip, Sjöström’s Ingmarssönerna, and various adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

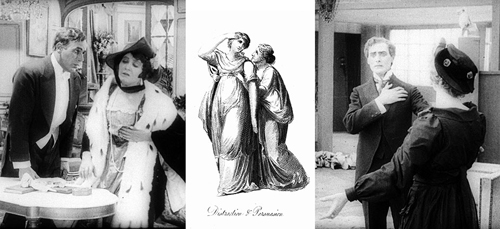

The twist here is that turn-of-the-century artistic culture had already blurred the boundaries between theatre and painting. Painters drew upon the stock gestures and poses of the stage, while plays presented vivid visual effects that were indebted to painting. The term “tableau,” referring at once to a picture and a poised stage image, captures this convergence between the media. That’s why Ben and Lea refer to “stage pictorialism” as the nexus of their inquiry.

Thanks to their research, we can see the unbroken long- or medium-shot of early features as permitting a complex choreography of facial expressions and bodily attitudes, which were in turn indebted to both pictorial and dramatic traditions. Standard gestures were summoned up and reworked to suit dramatic situations–as, for example, clutching.

When we do find editing or camera movements in these films, they’re often at the service of the performance style. Ben and Lea powerfully make the case that the expressive human body was at the center of storytelling in the first years of silent cinema. (If nothing else, the book is an in-depth analysis of diva acting from the likes of Lyda Borelli and Asta Nielsen.) By studying the history of theatre, we can learn to appreciate aspects of acting that might otherwise escape our notice.

Theatre to cinema to pixels

Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Slavery Days (Edison, 1903).

How, you’re asking, can you gain access to the ideas and information and images in this fine book? It’s now criminally easy.

When Theatre to Cinema was published, all the illustrations came from 35mm film prints. Those originals were gorgeous. But in some printings of the book the stills came out badly, and when the book moved to print-on-demand status, the images suffered even more. A couple years ago, Ben and Lea rescued their book and took the opportunity to make a digital version. It’s unrevised, largely because updating a twenty-year-old volume would be a major overhaul, but errors have been corrected and–very important–the stills have been much improved.

Start here, with the introduction to the project. You can download the new edition of the whole book, section by section, here.

Naturally, Kristin and I are sympathetic to this effort. Since we started our website back in 2000, we have explored ways to amplify and extend our ideas by means of the web. In the beginning, and inspired by Philip Steadman’s Net-based supplements to his excellent Vermeer’s Camera, I added material that would enhance arguments I made in Figures Traced in Light. Then we set up our blog, now in its tenth year. Over the same period, we posted web essays, as you can see in serried ranks page left. We also used the site to preserve older material, such as film analyses dropped from editions of Film Art: An Introduction and even entire books, as in Kristin’s 1985 monograph Exporting Entertainment. We’ve mounted video lectures. And we’ve produced a new edition of an older book, Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and original e-books such as Pandora’s Digital Box and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

Ben and Lea have found another way to expand a book’s Web life. They have put Theatre to Cinema at the heart of a digital collection sponsored by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries. Here’s what they offer:

In this collection, we try to supplement the description and illustration that accompanied the book in a way that makes it easier for readers to appropriate our work—both to understand it, and to make use of it in research and teaching. What were illustrations in the pages of the book are also presented here as better-quality downloadable images.

For example, you can pick a still, find its mates in a single display, and blow it up for scrutiny. If you want import it into your own files, you may choose among four different file sizes.

The provenance of each still is provided, so scholars can compare prints from different sources. In addition, there’s a master index of the visual documentation, in sequential groupings across the book.

Finally, Ben and Lea plan to add video extracts from some of the films they discuss. When those go up, we’ll announce it here.

Every admirer of silent film, and everyone who studies the interrelationship of the arts, should read this book. Hard copies are still being sold online, but they’re apt to be versions with weakly reproduced stills. Get one if you want, because a book is a good object to have in hand. In addition, for free, you can own a beautiful, searchable edition with superb stills. I think you need both.

The digital collections set up by UW Libraries are breathtaking. Check them out here.

Some entries on our site intersect with Ben and Lea’s research. See the category Tableau staging.

Weisse Rosen (White Roses, 1915). Asta Nielsen.

Manhattan wrapup: RHAPSODES and more

Aliza Ma and RZA at Metrograph, introducing screenings of Five Element Ninjas and House of Traps.

DB here:

We’re about to leave NYC after three months. I’ll miss all the movies and museums and food and friends, but I won’t miss the noise and congestion. I especially won’t miss the obliviousness of New Yorkers on the pavement–frowning into their cellphones as they nearly collide with you, steering baby assault vehicles as big as WW II half-tracks, and letting their longleashed pooches stray across streams of pedestrian traffic (there but for the grace of dog go I).

Okay, no more geezer complaints. Remarkable, the calming influence of an onion bagel with lox and cream cheese.

Our last days here have been really busy. Kristin gave a talk to the Egyptological Seminar of New York, “Beyond Thutmose: The District of Sculptors’ Workshops at Amarna” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Thursday. On Friday, I participated in a Film Comment podcast with critics Violet Lucca and Nick Pinkerton. We had a good time, talking about my book The Rhapsodes and other stuff. Here they are afterward in the Film Center.

Speaking of The Rhapsodes, Saturday I went to the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, where David Schwartz had mounted a four-film series tailored to the book. The first screening, Citizen Kane in a nice 35mm print, brought out a fair number of people.

Several people told me it was their first viewing of the film on the big screen, and indeed scale helps with this movie. It becomes more looming, from that screen-filling title onward, and you can see little details cunningly embedded. I noticed a couple of new items that I may write about later this summer. (Early in our stay, I already did a Welles birthday tribute here.) You always find more filigree in Kane; it looks forward to all our modern movies with in-jokes and Easter Eggs.

After Kane and a book signing (thanks, customers), I rushed off to Metrograph, a new venue with a consummate programming policy. There I met Aliza Ma, Jake Perlin, and their colleagues before catching the Chang Cheh double bill curated by none other than RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan. You see him with Aliza, in Scope of course, at the top of today’s entry.

On Sunday I caught up with Subway Cinema/ NY Asian Film Fest co-founder Goran Topalovic and critic-filmmaker Eddie Mullins (Doomsdays) at a wonderful Serbian restaurant. Much talk of Hong Kong film, of course.

On Sunday I caught up with Subway Cinema/ NY Asian Film Fest co-founder Goran Topalovic and critic-filmmaker Eddie Mullins (Doomsdays) at a wonderful Serbian restaurant. Much talk of Hong Kong film, of course.

Later that day, after seeing Hong Sangsoo’s latest, we had a late dinner with 125% cinephile Michael Barker, Co-President and Co-Founder of Sony Pictures Classics. Amidst talk of great 30s and 40s films, we learned that SPC is gearing up several new releases, notably the Cannes hit Toni Erdmann for December.

During my stay, The Rhapsodes came out and got several reviews already. It just picked up another, a wide-ranging, idea-packed discussion from one of Cinema Scope‘s best writers, Andrew Tracy.

Our last nights have been devoted to catching up with friends we’ve missed in earlier weeks. Above are Jerry Carlson and Deb Navins with Kristin in front of the Royal Tennenbaums house in their neighborhood. Below is a shot of Kristin and me with my college friend, film publicist and director’s representative Lucius Barre.

Our time here has just flown by. I finished a decent-ish draft of my 1940s book, but I haven’t done as much on other projects as I’d wished. I did, though, give talks at the Columbia Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation (thanks, Bill Luhr, Cynthia Lucia, and Krin Gabbard), Sacred Heart University (thanks, Sid Gottlieb and Sally Ross), Tufts University (thanks, Malcolm Turvey), Videology (thanks, Erik Luers and Austin Kim) and the 92nd Street Y (thanks, Alicia Harris-Fernandez). Going Upstate, as we New Yorkers call it, I gave the James Card Memorial Lecture at George Eastman Museum (thanks, Paolo Cherchi Usai and Jared Case), did some film viewing there, and visited the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. No less fun: I met Paolo Gioli at the Harvard Film Archive (thanks, Haden Guest; blogged here) and re-met Terence Davies at MoMI (thanks, David Schwartz; blogged here).

Our time here has just flown by. I finished a decent-ish draft of my 1940s book, but I haven’t done as much on other projects as I’d wished. I did, though, give talks at the Columbia Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation (thanks, Bill Luhr, Cynthia Lucia, and Krin Gabbard), Sacred Heart University (thanks, Sid Gottlieb and Sally Ross), Tufts University (thanks, Malcolm Turvey), Videology (thanks, Erik Luers and Austin Kim) and the 92nd Street Y (thanks, Alicia Harris-Fernandez). Going Upstate, as we New Yorkers call it, I gave the James Card Memorial Lecture at George Eastman Museum (thanks, Paolo Cherchi Usai and Jared Case), did some film viewing there, and visited the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. No less fun: I met Paolo Gioli at the Harvard Film Archive (thanks, Haden Guest; blogged here) and re-met Terence Davies at MoMI (thanks, David Schwartz; blogged here).

And to round things off, my blog entry on Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day is now available in Chinese here. Thanks to Jiahan Xu.

When I get back to Mad City, I must buckle down and revise the 40s book and, I hope, write a blog on types of film criticism today. Also, too: at our Cinematheque, another series dedicated to The Rhapsodes. (Yeah, the PR steamroller is relentless.) I’ll give an introductory talk and introduce the movies.

Is it lunchtime yet?