Archive for 2016

THE RHAPSODES goes to the movies

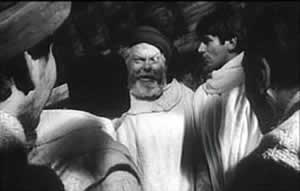

Counter-Attack (Zoltan Korda, 1945).

My little book on 1940s film critics has been lucky. It’s gotten more reviews, and gotten them more quickly, than anything else I’ve written in recent years. The online ones are by David Hudson at Fandor, Michael Curtis Nelson at PopMatters, and Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune. Not yet online, or available only through subscription services, are reviews by Geoffrey O’Brien (Artforum), Nick Pinkerton (Sight & Sound), and Dana Polan (Film Quarterly; the first page is available for free). All are generous and encouraging. I take the reviewers’ support to reflect the continuing appeal of four extraordinary writers who opened up fresh ways to think and talk about American cinema.

My little book on 1940s film critics has been lucky. It’s gotten more reviews, and gotten them more quickly, than anything else I’ve written in recent years. The online ones are by David Hudson at Fandor, Michael Curtis Nelson at PopMatters, and Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune. Not yet online, or available only through subscription services, are reviews by Geoffrey O’Brien (Artforum), Nick Pinkerton (Sight & Sound), and Dana Polan (Film Quarterly; the first page is available for free). All are generous and encouraging. I take the reviewers’ support to reflect the continuing appeal of four extraordinary writers who opened up fresh ways to think and talk about American cinema.

Coming up are two film series based on the book. At Astoria’s Museum of the Moving Image, David Schwartz has arranged a program of four films to play this weekend. Each is paired with a critic: Citizen Kane for Otis Ferguson, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre for James Agee, the little-seen Counter-Attack for Manny Farber, and The Picture of Dorian Gray for Parker Tyler. I’ll introduce Kane on Saturday and will hang around to talk with visitors, and copies of the book will be on sale.

After Kristin and I get back to Wisconsin, our Cinematheque will be running a comparable series across four weeks. Our programmer Jim Healy has put Sierra Madre, Counter-Attack, and Dorian on that bill as well, while our Ferguson pick is The Little Foxes. On 7 July I’ll introduce the series with a presentation. The full schedule is here.

If you’re in Astoria or in Madison, I’d be happy to see you!

On this site, of course there’s lots about Kane, most recently here. On The Little Foxes, try here and here.

P. S. 23 June 2016: James Wolcott, another remarkable critic-essayist (his work resides on my four-foot shelf), has kindly Tweeted about The Rhapsodes.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). “The Huston trademark consists of two unorthodox practices—the statically designed image (objects and figures locked into various pyramid designs) and the mobile handling of close three-figured shots” (Manny Farber).

A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY: Yang and his gangs

A Brighter Summer Day (1991).

If you care at all about the art of cinema, your task is simple.

1. Purchase, from whatever vendor you prefer, the new Criterion edition of Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day. Don’t rent or borrow or stream it. Forego a couple days of designer coffee and obtain the physical item. (Disclosure: I bought our copy, gladly.) If you can, go for the Blu-ray. This is a stupendously fine transfer. (Disclosure: I’ve seen the film several times on 35mm.)

1. Purchase, from whatever vendor you prefer, the new Criterion edition of Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day. Don’t rent or borrow or stream it. Forego a couple days of designer coffee and obtain the physical item. (Disclosure: I bought our copy, gladly.) If you can, go for the Blu-ray. This is a stupendously fine transfer. (Disclosure: I’ve seen the film several times on 35mm.)

2. Find the biggest screen you can. Ideally, use a public-access auditorium, a classroom, or an obliging arthouse venue. Don’t even think of watching it on a computer monitor.

3. Read Godfrey Cheshire’s helpful liner notes.

4. Watch the film (on the big screen, remember). It will take four hours.

5. After a decent interval, watch it again on a convenient screen, this time listening to Tony Rayns’ audio commentary. This is the most illuminating, subtle, and far-ranging audio commentary I’ve ever heard.

6. Explore the supplements: The touching documentary on Yang’s work with the young actors (An Actor’s Destiny: Chang Chen); Our Time, Our Story (a two-hour 2002 doc on New Taiwanese Cinema); and the 1992 Yang play Likely Consequence.

7. After a decent interval, watch the film again.

8. Entertain the prospect that you have seen one of the very great films of the 1990s, made available to us on one of the finest DVD editions ever mounted.

I could stop there, but you know I won’t.

Are you lonesome tonight? Who isn’t?

In my lead-in entry, I complained that film culture had been lamentably poky in making the films of Taiwanese directors Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang Dechang available on video. A Brighter Summer Day is a flagrant example. It arrives on commercial DVD twenty-five years after its initial release. Fortunately, it looks fresh and crisp as paint. As a movie experience, it’s more gorgeous and engrossing than any new release I’ve seen this year.

A Brighter Summer Day began as an independent production. Eventually, as Yang’s world expanded, outside funding was necessary to keep the production going. Over half the cast and crew had never worked on a film before, and the project took three years to complete. At a period when the Taiwanese film industry was virtually dead, Yang managed to mount a film of stunning ambition.

Although it was shot as a theatrical feature, it fits surprisingly well into today’s taste for long-form TV narratives. With over eighty speaking parts, it’s a very thick slice of life from 1960 Taipei. Indeed, Tony Rayns’ commentary reports that Yang said he had developed enough story material for three hundred TV episodes. If you like soaking in a richly realized world, here’s a movie made for you.

At the center stands Xiao Si’r, a fourteen-year-old boy having trouble in school. He tries to keep his distance from street-gang culture, but he becomes involved with turf wars while hanging out with his buddies. Si’r also attaches himself to the enigmatic schoolgirl Ming, who is pledged to a gang leader in hiding. A couple of his friends want to sing covers of rock-and-roll hits (most memorably Elvis’ “Are you lonesome tonight?,” the source of the English title). Yang has said that Americans don’t realize the subversive force of pop music in Taiwanese culture. “These songs made us think of freedom.”

To an extent, A Brighter Summer Day can be seen as an alienated-youth, juvenile-delinquent movie, complete with rumbles, tests of loyalty, and confrontations in pool halls and pop concerts. But Yang spreads his canvas in all directions. In the film’s second half, Si’r’s father, a nondescript bureaucrat, falls under suspicion as a political undesirable. That enables Yang to develop parallels between father and son, both stubbornly resisting authority. Meanwhile, the Zhang mother and older sister try to keep the family going in the face of overwhelming problems of school, home life, and political repression.

Widening the lens still further, Yang shows their neighborhood torn by tensions of class, job status, and ethnic identity. Jammed side by side are native Taiwanese families, mainland Chinese of long standing, and recent mainland arrivals who have fled the Civil War of 1946-49. Some families are quite poor, others lower middle-class, and others, such as those of military lineage, fairly well-to-do. The gang rivalries and the adult cliques replicate in miniature these splits and resentments. And the neighborhood plays host to a film studio, which the high-school boys invade in their off hours.

Across the months that the action consumes, the film depicts dozens of character vignettes and social encounters. As the scenes accumulate and the tension rises (the pacing is maniacally steady without being monotonous), gang warfare and political persecution culminate in a heedless, pointless knifing. I spoil you no spoiler, as the film’s Chinese title translates as “The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street.” In the course of the action, the film becomes an elegy to the ideals and errors of adolescence, a probing of the vanities of the male ego, a reflection on the pain of emigration, and a critique of social repression.

Starting from an actual incident doubtless recalled by some of the 1991 audience, A Brighter Summer Day builds out into what Yang called “a picture of an age.” The whole film, a magnificent piece of plot architecture, balances concrete individuality, as each character comes to vivid life, with a sense of how all fit into larger socio-political dynamics of one historical moment. Yet the characters aren’t mere place-holders or mouthpieces; they can surprise us by not behaving according to type. The well-off son of a general protects other boys from bullying, while the gang leader Honey, on the run for murder, turns from violence after reading War and Peace.

With this film Yang asserted himself as the equal to Hou Hsiao-hsien. Together, they lifted their nation’s filmmaking to world stature. You need only watch Criterion’s bonus documentary on Taiwanese New Cinema to see how, in about ten years, a sincere but somewhat patchwork local trend gained force, polish, and precision. In Hou’s films of the 1980s, from The Boys from Fengkuei (1983) and Summer at Grandfather’s (1984) to the masterpiece City of Sadness (1989), a modest regional realism grew into a monumental effort at historical understanding and cinematic innovation. Yang was doing the same in his own way, and A Brighter Summer Day became his response to Hou’s lyrical epic.

Two ways, at least, to be modern

Edward Yang Dechang.

The new generation of Taiwanese directors faced a local cinema divided between commercial genres (action, melodrama, romantic comedy) and government-sponsored “healthy realism” promoting a bucolic, idealized rural life. Like the Italian Neorealists, the New Taiwanese Cinema sought a more humanistic realism. The new films told humdrum but heartfelt stories using non-actors and deglamorized locations.

In this context, the ambitions of Edward Yang stood out sharply. While in America to work as a computer engineer, he dropped in and out of film schools. Returning to Taiwan to make a successful TV film, he began to explore contemporary life in his country through the forms made famous by Resnais, Antonioni, and their successors. He became Taiwan’s most Europeanized modernist.

The intricacies of That Day, on the Beach (1983) make other New Taiwanese Cinema films look rough-hewn. A concert pianist on tour meets her old school friend, and they talk over their lives. The pianist turns out to be a secondary character in a three-hour exploration of growing up and finding a career in contemporary society. There’s a mystery—the friend’s husband has vanished, perhaps by suicide—but, as in L’Avventura, the disappearance sends out ripples that reveal social pressures and psychological states. There are flashbacks, both fragmentary and extended; there are flashbacks within flashbacks; there are multiple narrators, replays of key events, and floating voice-overs—all in the service of probing the ways in which patriarchal authority stunts young people’s lives.

That Day, on the Beach is an essential film of its period and place, but unavailable in good video copies, as far as I know. Its revival is another task for Film Culture, Inc. to take up.

Taipei Story (1985) is more focused, but it reiterates Yang’s interest in parallel lives and parental control. The milieu would become Yang’s distinctive territory: modern corporate culture and its wearing away of local traditions and family ties. A couple are torn apart by the man’s loyalty to the woman’s profligate father, while she falls into a perfunctory round of flirtations. The couple talk of marrying and starting over in America, but the man, an inarticulate loser steeped in old-school business practices, can’t cope with the new world of clever executives, discos, and hooking up.

Yang came to festival attention with The Terrorizers (1986), one of the most experimental films of the New Cinema. It’s a network narrative, in which jerky coincidences connect a Eurasian girl, a doctor, a photographer, a policeman, and a novelist starting her new project. The nearly opaque opening presents a police raid in a jagged montage capped by a voice-over: “It was the first day of spring.” Thereafter it’s up to us to sort out the tangled connections, provoked by the Eurasian girl randomly phoning strangers to stir up trouble.

Once more Yang takes on male inadequacy, as the novelist’s husband becomes estranged from her and she launches an affair with a coworker. And once more Yang shows the individual succumbing to demands of the business world—not only the novelist’s office work but also the husband’s scramble to win a higher post in his hospital. Two final bloodbaths, one imaginary, counterbalance the opening.

Across these three features, Yang’s technique grew ever more polished. In filming company offices, he adroitly used windows and partitions to emphasize mistrust (Taipei Story, below left) and bureaucratic ennui (The Terrorizers, below right).

The novelist’s office break-room in The Terrorizers is a sleek pod, while the photographer’s studio is rendered as a wraparound photomontage. In an echo of Blow-Up, his obsession with the Eurasian girl is presented in an outsize mosaic of stills.

Along with his compositional skill, Yang showed himself an editing-oriented director. When the Eurasian girl limps out of the gun battle, she collapses on the sidewalk in three planimetric shots. The staccato images could almost be comic-book panels; Yang was an adept cartoonist.

A later pair of shots recalls the sequence. Yang often relies on stylistic repetitions to bind up an elliptical, degrees-of-separation plot.

In all these respects, Yang became something of a counterweight to Hou. Both were social realists, but they worked in competing domains. Hou tended to concentrate on life in the countryside, or on rural characters transplanted, bewilderingly, to the city. His tranquil style favored a reflective mood and muted emotion. His reliance on long takes, telephoto framings, static camera, and simple editing patterns (the axial cut-in being a favorite) made him appear in harmony with other New Cinema directors. By contrast, Yang probed yuppie life in cinematic terms that seemed more sophisticated and up-to-date.

Actually, Hou was forging an innovative style that owed little to 60s modernism. He relied on minute changes in lighting and staging within the distant, packed, fixed long take. We find this style emerging in his early commercial features, becoming refined in his New Cinema projects, and, in Dust in the Wind (1986) and Daughter of the Nile (1987), constituting a rich continuation of cinema’s tableau tradition. Hou’s work became a prime example of what came to be considered “contemplative cinema” and “Asian minimalism.” City of Sadness (1989) made this “neoprimitivism” (the phrase is Tony Rayns’) starkly apparent, as it blended with network-narrative plotting and an exceptionally oblique approach to exposition. Filmmaking has not been the same since.

Hou and Yang were exact contemporaries, both born (like me) in 1947. They had been friends and collaborators; Hou played the protagonist of Taipei Story, while Yang helped Hou with the score of The Boys from Fengkuei and took a role in Summer at Grandfather’s. They separated, as Yang did from nearly all his New Cinema comrades.

Given the importance of competition in artistic milieus, it’s not too much to suggest, as Tony Rayns does in the Criterion commentary, that the commercial and critical success of City of Sadness prodded Yang to boost his game. He too would launch a critical probing of his roots and of Taiwan’s past; he too would create a vast ensemble film. He would shift from office politics to real politics. And he would absorb and rework aspects of Hou’s style.

Backing off, stepping aside

A while back I distinguished between “stubborn stylists” like Bresson and Tati, who cling to their preferred techniques through thick and thin, and adaptable ones who modify their approach as broader norms change. The early films of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni were indebted to a deep-focus style, but late in their careers they began to rely on the pan-and-zoom techniques that became widespread in the 1960s and 1970s.

There’s another possibility, though. You the filmmaker can try out your rival’s methods, but then push them in directions that extend your own inclinations. The result can refresh your films and become part of your creative toolkit for future projects. This is what I think Yang did in A Brighter Summer Day.

Begin at the beginning. The opening moments introduce the rules, the intrinsic norms, of Yang’s film. During the credits, a hanging lightbulb is switched on.

Pulsating light becomes a multivalent motif throughout the film, carried via a flashlight, abrupt power cuts, and in a climax some hours later, a lightbulb smashed by a baseball bat.

As the credits continue, a flagrantly uninformative extreme long shot shows a man pleading with an unseen educator. He’s complaining about his son’s grades and asking about the boy’s transfer to a night school. Who is he? In probably the most unemphatic introduction of a protagonist in Taiwanese cinema, we get another extreme long shot of the boy we’ll come to call Si’r, waiting outside.

It’s Kuleshov constructive editing at work. There’s no long shot establishing the two spaces, nor can we assume that the first shot is, retrospectively, Si’r’s optical POV. But Kuleshov, who cared about punchy clarity, could hardly have approved of the far-off, information-stingy framings. Throughout the film we’ll see doorways block off parts of the action, extremely distant views frame a few scrubby figures, and shots dwelling on empty zones. This opening teaches us how to watch the movie.

Another rule: what Emilie Yueh-Yuh Yeh and Darrell William Davis call the tunnel-vision composition. This template is introduced in a perspective shot that waits ninety seconds for father and son to come to the foreground.

This first pair of scenes sets the task: We must suspend our craving for backstory and let the filmic narration slowly parcel out what we need to know—while still leaving a good deal to inference and imagination. Even more than Yang’s elliptical 1980s films, this is observational cinema, but with characters set at more than arm’s length.

Immediately, again with no establishing shot, we finally get a look at Mr. Zhang and Si’r seated at a food stall. Characterization is starting already, as we see the fretful father snuff out his cigarette and carefully save the butt. Much later he’ll quit smoking to save money.

Throughout, Yang will occasionally embed medium shots and closer views like these into his wide framings, anchoring his characters enough for recognition and revelation but not enough for the heated-up empathy encouraged by mainstream filmmaking. At various points, he will resort to shot/reverse shot as an accent within a more opaquely filmed scene.

These first few moments show how Yang has modified Hou’s signature devices. The shots seem poised between Yang’s earlier work and Hou’s tableau frames. Here the long shots tend to be either more distant or closer than Hou’s; Hou seldom uses the steep central-perspective imagery we see throughout Yang’s film; nor does Hou rely on the simple, straightforward medium shots we see in the food stall. Yang is, I think, blending his own inclinations with some tendencies revealed to him by City of Sadness and other films.

As if to push Hou’s preferences further, Yang stages many scenes with the camera set very far off. And instead of using a long lens to supply a frieze effect, with packed-in bodies shifting slightly this way and that, Yang’s frames are open and porous, though pocked with holes and streaked with shadow regions.

He will hold on frames devoid of human presence; as with Antonioni, a scene begins a bit before it begins and ends a bit after it ends.

One result is that “dedramatization” so prominent in postwar European art cinema. Even gang fights and deadly chases are observed with a dryness and detachment that allows us to appraise the action coolly. Yang’s shadowy, distant shots are the main reason you need to see this film on the biggest screen you can wangle. The first gang rumble and our initial sight of the family at dinner need scale to be legible. (Sorry I must post them so small.)

A major benefit of Hou’s dense staging is an emphasis on what I call his “just-noticeable differences.” Tiny shifts in character position reveal a detail to us, or pry open a view of something further back. Yang’s more open frames don’t exploit this as much. The frame at the top of today’s entry is a good example, with the heads spotted in the frame as a good cartoonist would.

In Hou’s City of Sadness, a scene of a gang confrontation is handled through tight timing and JND head-shifting that teasingly reveals facial expressions.

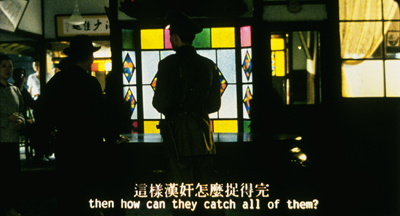

In A Brighter Summer Day, the wonderful scene of Honey’s return and Sly’s attempt to take over the gang is staged in a free lateral flow, with Cat scrambling into the frame again and again to break up the fight. Yang orchestrates bodies and faces for maximum clarity, moment by moment.

That horizontal staging is nicely broken by crucial movements along the lens axis, as first Ming and finally her boyfriend Honey come out from the area behind the camera and plunge into depth. The camera tracks gravely forward following him as he asserts his command.

There’s almost none of the blocking-and-revealing tactic that Hou relies upon. Yang’s framings are grave and spacious. More pragmatic than Hou, he’s willing to build the drama in a clear-cut fashion–as befits a director who sought to train a new generation of actors and who staged plays between his film projects. In this movie, I think, Yang found a middle way between his more disjunctive early style and Hou’s dense, blocklike tableaus.

Further evidence of this middle way is Yang’s revised attitude toward editing. Each of his 1980s films, while not subscribing to Hollywood’s frantic intensified-continuity principles, is built out of a great many shots. By contrast, the four hours of A Brighter Summer Day consist of only about 520 shots, averaging about 28 seconds each. The film contains several long takes and many single-shot scenes, so here we find him trying out the Hou approach. But as in the opening school sequence and the stall meal, editing does come into play during some tense conversations, notably when Si’r’s father is undergoing police interrogation.

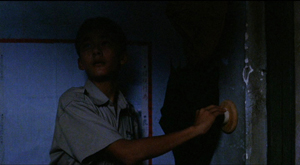

As at the start of Terrorizers, editing can occlude one crucial bit of action. What happened in that schoolroom during the gang raid? Yang’s choppy cuts respect the mere glimpse that Si’r gets of the boy and the girl who fled the room when he switched on the light.

In such passages, Yang’s abrupt cutting creates accents that break the attenuated, adagio rhythm of long, usually static shots. Here it adds to a central mystery of the film as well.

The elusive implications of the compositions and cuts are writ large in the film’s narrative rhythm. Here Tony Rayns’ magnificent commentary illuminates Yang’s artistry. Much of the story relies on local knowledge of Taiwanese culture, and Yang does not provide it in any direct way. Tony shows that every scene carries a historical and social subtext.

Just as important, story premises aren’t always spelled out; we’re expected to connect many dots. For example, nobody explains that Si’r’s eyesight is failing, and that he swipes the film studio’s flashlight so he can read more easily in his cramped bedroom. But because of his imperfect vision, he is getting injections of medicine, which take him to the school clinic and then to encounters with Ming and the doctor treating her. And Si’r’s father eventually toys with the possibility of buying him glasses on the installment plan (though then he’d have to economize by giving up cigarettes). Another film would have made a dramatic issue of Si’r’s vision problem; here, these story elements enter on the fringe of other dramatic action, mingle with other elements, and must be linked together by the alert viewer.

The result is that story motifs—the light bulb, the flashlight, the mother’s watch, a samurai sword, a vagrant snapshot, rock-and-roll tunes, baseball bats—don’t simply repeat across the film but rather mingle and overlap. Tony speaks of “resonances”; we could as easily talk of “ramifications.” Each prop or incident radiates in several directions, becoming a node in several plot lines. The dots we connect fuse in a multidimensional space. The strategy has affinities to Yang’s earlier films, but in none of them do we have this spacious dramatic density.

The film needs its four hours to develop all these motifs and to render events and milieus as gradually changing. The strongest example of this stepped development is Si’r’s “character arc,” which is rendered in a host of small moments, often treated indirectly or elliptically. Characteristically for Yang, as the climax approaches, our protagonist slips away from us—seen from the rear, kept offscreen, and ultimately as alone in a vast long shot as he had been at the beginning, but now turned steadfastly from us, as if defying us to understand and sympathize.

A Brighter Summer Day enabled Yang to absorb some stylistic extremes that were initially alien to him. He could find his versions of the distant, hard-to-read shot, without abandoning his commitment to more direct access to character reaction. Over-neat as it sounds, I’d argue that after trying out the Hou-ish options, he arrived at a new synthesis in his last three features. Two more social satires, A Confucian Confusion (1994) and Mahjong (1996), return to the cosmopolitan terrain of the early features. Now, however, there’s nothing so off-puttingly remote as many scenes in A Brighter Summer Day.

Chaplin said that comedy demands long-shot while tragedy lives in close-up. Yang begs to differ somewhat. A Brighter Summer Day gives us pathos in extreme long shot, but A Confucian Confusion yields comedy in mid-shot. Admittedly, however, those oblique doorways do their bit in mocking yuppie pretensions.

A Confucian Confusion closes with a nifty elevator shot displaying an easy command of classical staging.

Yang’s most widely-seen film Yi Yi (A One and a Two, 2000) shows the same synthesis at work for dramatic rather than comic purposes. Again, recurring locales and threaded motifs sustain a network tale anchored in family, neighborhood, and workplace. The familiar Yang clash of personal impulse and corporate corruption plays out in the cozy spaces of a household and the gridded confines of business hotels, company headquarters, and hospitals.

If Yi Yi seems to me a less daring film than A Brighter Summer Day, perhaps it’s because Yang has decided to work in a more traditional arthouse vein. For the first time in a Yang film, a child enters the mix. In the wake of Neorealism, many filmmakers realized that kids in movies can not only “defamiliarize” petty adult concerns; they can also attract audiences. But the presence of an unforgettable little boy shouldn’t be taken as a concession to international tastes. Little Yang’s camera-hound alertness adds a perspective that evokes the forbidding, oblique setups of A Brighter Summer Day: people with heads turned from us.

Edward brings his namesake into the plot comparatively late, to serve as a kind of observer and spokesman. “I want to tell people things they don’t know,” Yang Yang says at his grandmother’s funeral. “Show them things they haven’t seen.” It could be an epigraph for A Brighter Summer Day.

Thanks to Tony Rayns, as well as Curtis Tsui, Kim Hendrickson, and Peter Becker of Criterion. The best sustained discussion of Yang’s films I know is in the third chapter of Emilie Yueh-Yuh Yeh and Darrell William Davis’ Taiwan Film Directors: A Treasure Island (Columbia University Press, 2005).

Since its second edition of 2003, our textbook Film History: An Introduction has included extensive discussions of Hou, Yang, and New Taiwanese Cinema. I’m proud that we gave attention to these filmmakers when other world cinema surveys ignored them. I discuss Hou’s style at length in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging and in these web entries. There’s a sidebar on A Brighter Summer Day in the book as well.

I met Edward a couple of times in the 1990s, most memorably at the Kyoto Film Festival. I’ll always remember him pedaling his rented bike around town but always ready to have a meal and talk about the films he loved.

I wrote a valedictory on Edward’s death here. Today’s entry picks up a couple of points made there.

P. S. 28 June 2016: Thanks to Carman Tse for correction of my spelling of the family’s name. Carman points out that the protagonist’s proper name is Chang Chen, the same as the actor’s own name. (“Chang” is a common Westernization for “Zhang,” the family’s name.) Carman adds, as I should have, that Xiao Si’r means “Little Fourth Son,” a point also made in Tony Rayns’ commentary and Godfrey Cheshire’s liner essay. Because the subtitles, Tony’s commentary, Godfrey’s essay, and much critical writing on the film refer to the boy as Xiao Si’r, for the sake of consistency that’s the one I’ve retained in the piece.

A Brighter Summer Day.

THE RHAPSODES comes to Videology

Tonight at 7 I’ll be at Videology, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Thanks to Erik Luers and Austin Kim for inviting me. We’ll talk about film critics of the 40s (Agee, Farber, Ferguson, Tyler) and–I hope, film reviewing today. (I have things to get off my chest.) If you’re in the mood and in the neighborhood, why not come by? There’ll be copies of the book around, and order forms for discount copies as well.

Lest this look too monastic, recall that there’s also this.

Videology info here: http://videologybarandcinema.com/.

Hou Hsiao-hsien: Film culture finally comes through

The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982).

For today, let’s call “film culture” that loose agglomeration of institutions around non-mainstream cinema. Film culture includes art house screening venues, festivals, magazines like Film Comment, Cinema Scope, and Cineaste, distribution companies (Janus/Criterion, Milestone, Kino Lorber et al.), critical websites, and not least the new channels of distribution and exhibition like Fandor, Mubi, and the impending FilmStruck.

Although the system is decentralized, there’s usually a fairly predictable flow of films through it. A film is shown at festivals, written up by critics, and picked up by distributors. Then it gains some exposure in theatres or more festivals, and it eventually becomes available on DVD, cable, and streaming services. And now we expect the process to move fairly quickly. Mustang played Cannes and many festivals through summer of 2015; it moved to theatres in the US and elsewhere in the fall. Only a year after its premiere, you can buy it on disc.

We’ve also been aided by the emergence of multi-standard video players and the willingness of some disc-publishing companies to release versions with subtitles in several languages. All too often, though, “film culture” displays gaps and delays. It took six years for Asgar Farhadi’s wonderful About Elly (2009) to make its way to minimal visibility in the US. Fans of Godard have been prepared to wait years to see his many films that didn’t get even video release in English-speaking territories. (Soigne ta droite! played Toronto in 1987, never got a theatrical release in America, and showed up on US DVD in 2002; the Blu-ray came out eleven years after that.) Two of the most egregious examples of this time lag involve the works of the outstanding Taiwanese filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s: Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang.

Most of Hou’s films had no proper US release. When they were available for booking, as from Wendy Lidell’s heroic International Film Circuit, they circulated for one-off screenings. Some of his major films, such as City of Sadness (1989), still remain difficult to see. Edward Yang’s work was similarly obscure. When we ran a retrospective at our UW Cinematheque in 1998, we had to borrow prints from his family.

Most of Hou’s films had no proper US release. When they were available for booking, as from Wendy Lidell’s heroic International Film Circuit, they circulated for one-off screenings. Some of his major films, such as City of Sadness (1989), still remain difficult to see. Edward Yang’s work was similarly obscure. When we ran a retrospective at our UW Cinematheque in 1998, we had to borrow prints from his family.

Both of these extraordinary filmmakers had to wait many years for the exposure that is standard for European arthouse releases. After six features in seventeen years, Yang found a Western audience with Yi Yi (2000). Hou took even longer; twenty-seven years after his first feature, he gained some recognition with The Flight of the Red Balloon (2007) and last year, The Assassin. Meanwhile, many of these directors’ early films remain largely unknown, prey to ancient distribution contracts and the belief that the films would cost too much to revive and market.

Today’s entry and the next one celebrate the welcome news that important works by these two filmmakers are at last available on the disc format. Today I’ll concentrate on the three early Hou films from the Cinematek of Belgium: Cute Girl (1980), The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982), and The Boys from Fengkei (1983). Next time, I’ll consider Criterion’s release of Edward Yang’s masterpiece A Brighter Summer Day (1992).

Hou, early and late

Hou’s films are no stranger to this site. Among the first things I posted, back in 2005, was one of a batch of supplemental essays to my book, Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging (2005). That book devoted a chapter to Hou’s staging principles, with background on what I took to be the evolution of his technique. It was, I think, the first sustained view of Hou’s style, and it included discussion of his earliest films. These were scarcely known in the West and not considered in relation to his more famous work.

The online essay expanded my treatment of those titles. Because that essay is more or less buried elsewhere on the site, and it’s somewhat clunkily laid out by today’s standards, I’m reprinting it, with revisions, here, along with some bits from Figures. But first some background on these early works.

Hou began in the commercial, mainstream Taiwanese-language industry. Most local films had a strong genre identity: martial-arts movies, romantic comedies, or melodramas of family crises. Hou’s first directorial effort, Cute Girl, centered on a romance between two city dwellers who re-meet when the man is called to a surveying task in the countryside. Cheerful Wind (1981) reunites the two stars, Kenny Bee and Feng Fei-fe, in a more serious story of how he, a blind man, wins her love. In the pastorale The Green, Green Grass of Home, Kenny plays a schoolteacher brought to a village, where he meets another teacher and a romance blossoms. This film, however, expands to include dramas, big and small, involving several families; it also incorporates an ecological theme by encourage safe fishing policies.

In making these early films Hou discovered techniques that not only suited the stories he had to tell but also suggested more unusual possibilities of staging. He pushed those techniques further in his later films, with powerful results. The charming early films show him developing, in almost casual ways, techniques of staging and shooting that will become his artistic hallmarks. One basis of his approach, I argue, is his adoption of the telephoto lens.

How long is your lens?

Around the world, from the late 1930s through the 1960s, many films relied on wide-angle lenses—those short focal-length lenses that allowed filmmakers to stage action in vivid depth. One figure or object might be quite close to the camera, while another could be placed much further in the recesses of the shot. The wide-angle lens allowed filmmakers to keep several planes in more or less sharp focus throughout, and this led to compact, sharply diagonal compositions, as in Welles’ Chimes at Midnight (1966).

Although Citizen Kane (1941) probably drew the most attention to this technique, it was occasionally used in several 1920s and 1930s films made throughout the world. The great French critic André Bazin was the most eloquent analyst of the wide-angle aesthetic, and his discussion of Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), The Little Foxes (1941), and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) has strongly shaped our understanding of this technique.

The 1960s saw the development of an alternative approach, what we might call the telephoto aesthetic. Improvements in long focal-length lenses, encouraged by the growing use of location shooting, led to a very different sort of imagery. Instead of exaggerating the distances between foreground and background, long lenses tend to reduce them, making figures quite far apart seem close in size.

In shooting a baseball game for television, the telephoto lens positioned behind the catcher presents catcher, batter, and pitcher as oddly close to one another. Planes seem to be stacked or pushed together in a way that seems to make the space “flatter,” the objects and figures more like cardboard cutouts. The style was popularized by films like A Man and a Woman (1966).

The telephoto look quickly spread, employed by directors as diverse as Sam Peckinpah and Robert Altman, whose 1970s films also use the long lens, controlled by zooming, to squeeze a crowd of characters (M*A*S*H, 1972; Nashville, 1975) into the fresco of the anamorphic frame.

Hou Hsiao‑hsien came to filmmaking via the romance films so common in Taiwan in the 1970s, and this genre employed the long lens extensively. Working with low budgets, most filmmakers relied on location shooting. The telephoto allowed the camera to be set far off and to cover characters in conversation for fairly lengthy shots (as in Diary of Didi, 1978, below). In this respect, the directors were not so far from their Hollywood contemporaries; Love Story (1970) employs these techniques on a bigger budget.

Indeed, Love Story (a big hit in Taiwan) may have pushed local filmmakers toward using this technique in their own romantic melodramas; sometime the influence seems quite direct (Love Story and Love Love Love, 1974)

With these norms in place, Hou’s inclination toward location shooting and the use of nonactors, along with his attention to the concrete details of everyday life, allowed him to see the power of a technique that put character and context, action and milieu, on the same plane. His crowded compositions are organized with great finesse in order to highlight, successively, small aspects of behavior or setting, and these enrich the unfolding story, as Figures tries to show in his masterpieces of the 1980s and 1990s. Using a long lens (usually 75mm–150mm) he began to exploit some “just-noticeable differences” that the lens creates as byproducts.

Hou saw unusual pictorial and dramatic possibilities of the telephoto lens, and they became central to his distinctive way of handling scenes. A current norm of production practice yielded artistic prospects which he could explore in nuanced ways. Figures provides the detailed argument, but let me highlight three points here.

Exploiting the flaws

Flowers of Shanghai (1998).

One byproduct of the long lens is a shallow focus, as we can see in the examples above. Because the lens has little depth of field, one step forward or backward can carry a character out of focus. Hou stages in depth–and at a distance–but allows the layers to slip out of focus gradually.

Savoring the effects of gently graded focus is a common feature of Hou’s later work. The masher at the train station in Dust in the Wind (1987) moves eerily in and out of focus in the distance. In Daughter of the Nile (1988), there’s an astonishing shot showing gangsters approaching a victim’s SUV outside a nightclub: at first they’re only barely discernible blobs (seen through the vehicle’s narrow windows) but then they gradually come into ominously sharp focus in the foreground, preparing to attack one of the boys inside. The slight changes of focus train us to watch tiny compositional elements for what they may contribute to the drama. More recent examples abound in Flowers of Shanghai (1998), above, where it’s the foreground planes that dissolve.

Hou’s three first films don’t use the option quite so daringly; here the degrees of focus concentrate on the principal players but still allow us to register the teeming life around them (Cute Girl; Green, Green Grass).

Hou can put sharply different dramatic situations on different layers. In Green, Green Grass, the departure of the little girl, saying farewell to her host family, plays out slightly closer to the camera than the departure of the eccentric teacher.

This principle operates as well in the creatively distracting street and train-platform scenes of Café Lumière (2004).

Secondly, the long lens yields a flatter-looking space. It has depth, but the cues for depth that it employs are things like focus, placement in the picture format (higher tends to be further away), and what psychologists call “familiar size”—our knowledge that, say, children are smaller than adults, even if the image makes them both of equal size. One favorite Hou image schema is the characters stretched in rows perpendicular to the camera, and the telephoto lens, by compressing space, creates this “clothesline” look more vividly. We can find the clothesline staging schema in the early Hou films (Cute Girl, Cheerful Wind).

Another favorite schema is the “stacking” of several faces lined up along a diagonal (Cute Girl). This can be seen as a refinement of a schema that was in wider use, as an example from Love Story indicates.

But Hou uses this sort of image more subtly. The telephoto lens lets him stack faces in ways that encourage us to catch a cascade of slight differences (Millennium Mambo (2000)). In many scenes of Flowers of Shanghai (1998) this principle is carried to a degree of exquisite refinement without parallel in any other cinema I know. In one shot, the faces are stacked in the distance, behind a lantern, and a slightly shifting camera reveals slivers of them.

In general, because Hou is committed to a great density of information in the shot, the compression yielded by the long lens tends to equalize everything we see. Minor characters, or just passing strangers, become slightly more prominent, while details of environment can get pushed forward as well. The zoo scenes of Cute Girl enjoy showing us our characters in relation to the creatures around them.

In the shot surmounting today’s entry, the tile rooftops of The Green, Green Grass of Home, secured by bricks and pails and tires and baskets, become just as important as the figures below them.

In Green, Green Grass, Hou develops the equalized-environment option in one particular scene. A long-lens distant view catches the teacher coming to the father’s house along a corridor of rooftops.

When the teacher confronts the father, instead of tight framings on each man, Hou cuts to another angle that activates yet another range of environmental elements—principally the train passing in the background, prefiguring the trip that the man’s son and daughter will take in an effort to find their mother.

Because the long lens has a very narrow angle of view (the opposite of a “wide-angle” lens), it affects the image in a third major way. If you use a long lens in a space containing several moving figures, people passing in the foreground will block the main figures: they pass between the camera and the lens. Hou elevates this blocking-and-revealing tendency to a level of high art.

In Figures Traced in Light, I argue that many great directors, from the silent era forward, have staged action in the shot so as to block and reveal key pieces of information, calling items to our attention at just the right moment with unobtrusive changes of figure position. The possibility of blocking and revealing arises from the “optical pyramid” created by any camera lens. (Lots more on that pyramid in Figures and in this video lecture.)

Hou showed himself capable of using the blocking-and-revealing tactic in traditional ways. Take this simple encounter in Green, Green Grass, when the new teacher Da-nian meets Su-yun, the young teacher with whom he’ll fall in love. The scene begins on him, then cuts to a reverse angle as he’s introduced to the principal.

The others are turned toward the principal in the background; the whole composition pushes our eye toward him. Then the teacher steps left to judiciously block the principal. The woman on the far left turns her head and we’re nudged to look at her. Da-nian swivels slightly too.

Then the key introduction: Da-nian shifts aside a little, the teacher continues to block the principal, and the central woman turns toward us.

The climax (quiet, nifty) of this shot comes when Su-yun rises to meet Da-nian. She commands the center of the frame, frontal and radiant. Like any good classical director, Hou then gives us a reaction shot mirroring the first shot of this “simple” sequence: Da-nian is more than happy to meet her.

Imagine how a contemporary Hollywood director would handle this–lots of cuts, everybody in singles and close-ups, transfixing track-in to Su-yun, maybe a boingo music track–and count yourself lucky to have encountered, for once, an unfussy craftsman.

Hide and seek

The Green, Green Grass introduction scene involves a wide-angle lens, but Hou’s skill with slight character movement shows up in long-lens images too. In fact, I suspect that using the telephoto lens on location made him sensitive to the resources of masking and unmasking bits of the shot.

The loveliest example I know in the early films is the Cute Girl shot I analyze in Figures, when Fei‑Fei confronts the surveyors and the man in the red shirt serves as a pivot for our attention; the staging shifts our eye back and forth across the frame, according to small changes of character glance.

A less drastic example occurs when the surveying team starts quarrelling with the locals around a walled gate: The team’s blocking of the gate gives way to movement into depth and a struggle there between them and the townsfolk.

In all, it seems to me that these three resources of the long lens—the shallow focus, the compressed space, and the narrow angle of view—supplied artistic premises for Hou’s shooting and staging in the later films. This is not to ignore his use of the wide-angle lens on occasion, particularly interiors, as in the schoolteachers’ introduction scene. Once the lessons of the long lens had been absorbed, Hou could apply the staging principles that he’d developed to other kinds of shots and story situations. Sometimes he kept his style smooth and limpid, but at other times he offered the viewer some unusual challenges.

Peekaboo pictures

The Boys from Fengkuei (1983).

Presumably Hou could have kept making good-natured, crowd-pleasing movies for many years, but changes in his professional milieu gave him new opportunities. In the early 1980s Taiwan film attendance declined sharply, and Hong Kong films began to command more attention than the local product. The rash of independent companies had concentrated on speculation, not long-term investment, so only the government’s Central Motion Picture Company could initiate recovery. Ambitious government officials launched a “newcomer” program that offered support for cheap films by fresh talents. Even if the new films could not win back the local audience, they might gain renown at foreign film festivals. At the same period, a local film culture began to emerge, relying upon critics who were sympathetic to the creation of a New Taiwanese Cinema.

Hou was no newcomer, but working within the New Cinema framework he could reconceive his practice. The key question for all directors, he recalls, was: What is it to be Taiwanese? His New Cinema films would focus on political and cultural identity, and they did it through an approach to cinematic storytelling that in many respects ran against the conventions of his earlier films. His first New Cinema feature, The Boys from Fengkuei (1983; included in the Cinematek set) reminds us of how “young cinemas” have often represented a return to Neorealism.

Instead of introducing us to clear-cut protagonists and a dramatic situation, the film immerses us in a milieu, that of the small town of Fengkuei. The first fifteen minutes are episodic, casually showing a gang of teenage boys playing pool, lounging about, playing pranks, and above all getting in fights. Initially, the one who’ll become the main figure is minimally characterized; the emphasis, as the title indicates, is really on the group. The boys drift to the big city, where they try to get by and meet others their age. Throughout, local color and everyday routines drive the action more than character goals and traditional drama do.

This somewhat diffuse approach to narrative, in various countries, has proven well-suited for filmmakers who want to explore psychological development and social-cultural commentary. So it accords with the impulse toward understanding national identities that animated New Taiwanese Cinema. In addition, I think that this looser conception of storytelling allowed Hou to refine some of the stylistic options he had already explored. Now the extended, fixed telephoto shot with varying planes of focus appears as a more indeterminate pictorial field, as in our rather oblique introduction to the boys–partial framed figures drifting in and out of the frame–and their poolroom hangout. Emphasizing incomplete views and vague figures outside the door, Hou gives us a more precise array of balls on the table than he does of his characters in space.

Likewise, even though Hou has surrendered his very wide anamorphic frame, he finds ways to balance human action and tangible surroundings in the ways he did with city landscapes and village rooftops in the earlier films. The bullying of a motorcyclist and a pursuit by a rival gang aren’t rendered with the aggressive cuts and angles we’d expect in violent scenes in the Hong Kong action pictures then ruling Taiwanese screens. It’s as if Hou, along with his colleagues, is rejecting that other Chinese-language tradition.

Which is to say that when conflict comes, Hou turns to “dedramatization,” that tendency (again related to Italian Neorealism and its successors) of tamping down peaks of action. Now his characteristic long lens creates detached shots, sometimes with planimetric flatness, sometimes with tunnel vision. These images play out chases and fights in a way that minimizes their physical impact but reminds us of the design and details of the characters’ world.

Hou’s insistence on the fixed, distant telephoto take is now put in the service of obscured vision. The people who passed through the frame in the earlier films, blocking and revealing the action judiciously, may become more salient than the action itself–which is itself often offscreen, or swathed in shadow, or shielded by aspects of setting. The early films’ fixed long take enabled us to see story action fully, but, now, in its refusal to cut away, the camera can suppress story information.

Early in the film, a street fight passes in and out of a far-off intersection among stalls. The dust-up stirs only slight interest from passersby, before bursting back into the alleyway and coming to the camera.

The masking of the fight by the setting can be seen as an extension of the way the walls in the Cute Girl surveying quarrel intermittently cut off our vision, but here it’s far more drastic and sustained.

I’ve drawn my examples from the early stretches of The Boys from Fengkuei, so as not to preempt your own discoveries as the plot carries the gang to the big city. In these scenes Hou in effect teaches us how to watch his movie. But I think I’ve said enough to suggest how Hou’s fresh conception of narrative, born of a renewed interest in local culture (already present in another register in the first three films), allowed him to carry his stylistic explorations to new levels.

Hou saw certain pictorial possibilities in the long lens, and after developing them to a certain point in popular musicals, he recast them when he took up another kind of storytelling. He realized that leisurely, contemplative narratives permitted him to refine these visual possibilities, and they could become powerful, nuanced stylistic devices. And he didn’t stop, as the films following his New Cinema works vividly show. His visual imagination seems unlimited.

A more general lesson follows from this. Norms of form and style are resources for artists. Some artists follow the schemas that they inherit, while others probe them for fresh possibilities. A few can even make a handful of schemas the basis of a rich, comprehensive style. Ozu did this with the techniques of classical Hollywood editing; Mizoguchi did it with depth staging in the long shot. Like these other Asian masters, Hou reveals how much nuance a few techniques can yield, even when deployed in crowd-pleasing, mass-market movies. And now, thanks to the vagaries of film culture, more viewers can come to appreciate his achievement.

The frames from Diary of Didi and Love, Love, Love are, alas, cropped video versions, but that condition doesn’t keep us from recognizing the telephoto lensing in the originals.

The Cinematek collection also includes sensitive English-language introductions to the films by Tom Paulus and enlightening audiovideo essays by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin.

The indispensable English-language sources on Hou are James Udden’s in-depth career survey, Richard Suchenski’s monumental anthology, Emilie Yeh and Darryl Davis’ study of New Taiwanese Cinema, and two monographs on City of Sadness, one by Bérénice Reynaud, the other by Abe Markus Nornes and Emilie Yeh.

The fullest account I’ve offered of Hou’s style are in Figures Traced in Light and in a video lecture, “Hou Hsiao-hsien: Constraints, traditions, and trends.” See also the several blog entries touching on his work. A broader account of the historical tradition to which he belongs can be found in both Figures and On the History of Film Style, as well as in entries under Tableau staging and in the video lecture mentioned already.

The Boys from Fengkuei.