Archive for February 2016

Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations

The Hateful Eight (2015).

DB here: Jeff Smith, our collaborator on the new edition of Film Art, is an expert on film sound. He has written earlier entries on Atmos and Trumbo.

The Academy Awards ceremony is upon us. Once again this year, I offer an overview of the two music categories: Best Original Song and Best Original Score. For the songs and some score cues I’ve provided links, so you can listen as you read.

This year’s nominees showcase music written in an array of musical styles for a wide range of narrative contexts. The composers and songwriters recognized for their work include some newcomers, some savvy veterans, and a pair of legends who have helped to define the modern film score.

As always, this preview is offered for non-sporting purposes. Anyone seeking insights for wagers or even the office Oscar pool is duly cautioned that they assume their own financial risks for any information they use. And since I was only half-right with last year’s prognostications, you might seek predictions from insiders at Variety and Entertainment Weekly.

Diversity in numbers: Best Original Song

Fifty Shades of Grey (2015).

When the Oscars were announced a few weeks ago, they made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Noting the lack of racial diversity among the acting nominees, social media exploded, creating #OscarsSoWhite as a popular Twitter handle to draw attention to the situation. After a cacophony of tweets and retweets, several celebrities weighed in. Will Smith and others suggested that they planned to boycott the ceremonies.

The nominees for Best Original Song, though, are a pretty significant exception to the OscarsSoWhite meme. Both the performers of these five songs and the topics they address reveal that Oscar voters haven’t entirely ignored the fact that films can be a force for social change.

The Weeknd’s breakout year on the pop charts has continued with an Oscar nomination for “Earned It” from Universal’s hit of last spring, Fifty Shades of Grey. The Weeknd’s “Can’t Feel My Face” has enlivened playlists all year long, but “Earned It” is a slow-burn soul ballad that accompanies Christian and Anastasia’s ride home after his mother interrupts their morning tryst. The song was co-written by the Weeknd, Belly, Jason “Daheala” Quenneville, and Stephan Moccio, and features a simple two-chord pattern on the piano that eventually builds toward a more harmonically adventurous string passage. According to Moccio, the song was intended to reflect a male perspective, hinting at the darkness lurking underneath Christian’s sexual peccadillos.

The Weeknd, Quenneville, and Belly are all Canadian. But considering that the Weeknd and Quenneville are of African descent and that Belly is of Palestinian heritage, their nomination offers a modest riposte to the criticism leveled at the Oscars for their lack of racial diversity. However, since their song appears in one of the more critically reviled films to receive a nomination, it seems unlikely that “Earned It” will take home the prize next Sunday.

Tuning up nonfiction films: Nominated songs from docs

Racing Extinction (2015).

Two other nominations come from recent documentary films, continuing a trend begun with last year’s nod to Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me. The first is for J. Ralph and Antony Hegarty’s “Manta Ray” from Racing Extinction, which examines the threat man poses to the survival of several bird species, amphibians, and marine animals.

Hegarty is only the second openly transgender person to receive a nomination, a quite pleasant surprise for fans of her work as a singer and songwriter. Hegarty initially made a splash in 2000 with the release of her band’s debut album, Antony and the Johnsons. Her breakthrough, though, came with the 2005 release I Am a Bird Now, which topped several critics’ year-end lists and won Britain’s prestigious Mercury Prize.

“Manta Ray” is a delicate waltz based upon a central theme from J. Ralph’s score for Racing Extinction. Although the song itself appears only over the closing credits, Ralph’s theme threads through the film, introduced during a key scene when a member of the filmmaking team removes a hook and fishing line from a manta ray’s dorsal fin. After the SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, commercial fishermen increasingly targeted manta rays since their gills were thought to have curative powers among practitioners of Chinese folk medicine.

Anchored by her soft, tremulous voice, Hegarty’s music has always exuded sensitivity and melancholy in almost equal measure. With Hegarty’s ethereal tones floating over Ralph’s simple piano accompaniment, “Manta Ray” not only captures the animal’s grace and beauty, but also hints at the tragedy of their steady decline.

Racing Extinction is not Hegarty’s first brush with Hollywood. Previously, her music was featured in James McTeigue’s V for Vendetta and in Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There. But given all the media attention to the Oscars, Sunday night will offer Hegarty a much bigger stage and a chance for the world to see her extraordinary gifts.

The other nominated song from a documentary is “Til It Happens to You,” which was written for Kirby Dick’s searing documentary on campus rape, The Hunting Ground. The film not only exposes college administrators’ efforts to cover up incidents of sexual assault, but also shows how two University of North Carolina rape survivors used Title IX legislation to draw attention to the problem.

“Til It Happens to You” brought Lady Gaga her first nomination and Diane Warren her eighth. Beyond the sheer star power brought by the pair, Gaga and Warren both have discussed their own experience as rape victims.

According to Variety, Gaga worried that the gravity of the film’s subject matter might not square with her outlandish diva persona: “I was very concerned that people would not take me seriously or that I would somehow add a stigma to it.” But her concerns appear to be unfounded. Warren reports that other survivors have reached out to her saying that the song and film is “making people feel less alone.”

Some of this reaction undoubtedly derives from the emotional gut punch delivered by the song’s lyrics. They not only describe the feelings of devastation felt by rape victims. They also express the difficulty of dealing with unfeeling bureaucrats and callous peers. The refrain of “Til It Happens to You” conveys the sense of isolation created by others’ inability to fully know what it’s like to walk in the victim’s shoes.

Licensed to Trill: The Spectre of Youth

Spectre (2015).

Jimmy Napes and Sam Smith’s “Writing’s On the Wall” from Spectre adds another notch to James Bond’s gunbelt. Four previous Bond films have received nominations for Best Original Song. And in 2013, British chanteuse Adele took home a golden statuette for the title track of Skyfall.

For me, the piece is well crafted, but falls somewhere in the middle of the Bond music pantheon. Not quite the peaks of Shirley Bassey’s “Goldfinger” or Paul McCartney’s “Live and Let Die.” But also not the dregs of Rita Coolidge’s “All-Time High” or A-ha’s “The Living Daylights.” “Writing’s On the Wall” is vaguely Bond-ish in much the same way that Smith’s smash hit, “Stay With Me,” contained strong echoes of Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down.”

The last nominee is “Simple Song #3” from Youth. Of all the nominees, David Lang’s piece is the one most firmly integrated into the film’s narrative. “Simple Song #3” is featured at the end of Youth, performed onscreen by singer Sumi Jo, violinist Viktoria Mullova, and the BBC Concert Orchestra.

The song is a classic “Adagio” structured around a repeated descending string figure. Gradually, other instruments are added, creating patterns of shifting harmony that surge beneath Jo’s vocal line.

Although “Simple Song #3” doesn’t appear till the end, the song is mentioned at several earlier moments as the work of the film’s protagonist, Fred Ballinger (Michael Caine). Ballinger is a retired composer and conductor lured back to the stage by an invitation from the Queen to perform for Prince Philip’s birthday. According to Lang, the piece offers a window into Ballinger’s psychology. It balances both the aspirations of his youth with the melancholy of a life lived apart from the woman he loved.

Placed in the film’s climax, Ballinger’s work provides an emotional capstone that operates at several levels. Given the complexity of its narrative function, “Simple Song #3” is not so simple.

Prediction: As a longtime Antony and the Johnsons fan, I would be delighted to see Hegarty and Ralph making their acceptance speech on Sunday night. But it seems to be Lady Gaga’s year so far. After winning a Golden Globe for her work on American Horror Story: Hotel, singing the national anthem at the Super Bowl, and performing a tribute to David Bowie at the Grammys, Gaga will cap off a stellar start to the new year by walking home with Oscar on her arm. It will also provide career recognition to Diane Warren, whose music has graced more than 200 different films and television shows. After last year’s disappointment, Warren finally will get the opportunity to be forever “Grateful.”

Old White Men and Even Older White Men: Best Original Score

Sicario (2015).

The nominees for Best Original Score are a group of seasoned craftsmen who collectively have received more than seventy Oscar nominations and have written music for more than seven hundred feature films. At age 46, Jóhann Jóhannsson is the youngster of the group. Carter Burwell and Thomas Newman both turned sixty late last year. And John Williams and Ennio Morricone are both octogenarians.

Jóhannsson is nominated for his score for Denis Villeneuve’s drug war thriller Sicario. The Icelandic composer received a nod last year for The Theory of Everying, but lost out to Alexandre Desplat’s charming Euro-pudding score for The Grand Budapest Hotel.

The score for Sicario, though, couldn’t be more different than that for The Theory of Everything. Where Everything’s music was lilting and lyrical, Sicario’s is tense and ominous, emphasizing rhythm, timbre, and texture over more conventional structures of melody and harmony. Several cues are organized around pounding drum patterns punctuated by sustained, dissonant blasts of strings and low brass. In an interview, Jóhannsson recalled, “I think the the percussion came first, and then I started to weave the orchestra into it. Very early on I decided to focus on the low end of the spectrum—focus on basses, contrabasses, low woodwinds, contrabassoon, contrabass clarinets and contrabass saxophone.”

Other cues also emphasize percussive textures, but with the instrument sounds processed so that they sound driven to the point of distortion. Even a more restrained cue like “Melancholia” still maintains a quiet intensity, structured around a cyclic harmonic pattern played on acoustic guitar in a vaguely flamenco style. The score is brutally effective in capturing the mood of Sicario’s taut action scenes. In fact, for me, Jóhannsson’s score was, without question, the best thing in the film.

The Old Hands: Carter Burwell and Thomas Newman

Carol (2015).

Carter Burwell received his first Oscar nomination this January for his score for Todd Haynes’ Carol. Burwell got his start on the Coen brothers’ debut, Blood Simple (1984), and has been a regular collaborator ever since. He has also worked regularly with a number of other filmmakers, such as Charlie Kaufman, Spike Jonze, and Bill Condon. Given the rather quirky and absurdist tone found in many of their projects, Burwell’s great gift is to provide music that emotionally grounds the characters, finding notes of lyricism, melancholy, and pathos in the strange stories of lovelorn puppeteers, sex researchers, and bumbling kidnappers.

For Carol, Burwell tried to capture the peculiar mixture of passion and distance that characterizes Therèse’s initial attraction to Carol. Because Carol comes across as both elegant and a bit aloof, Burwell not only utilized ambiguous harmonies, but also “cool” instruments, such as piano, clarinet, and vibes.

On his website, Burwell identifies three main musical themes in his score for Carol. The first is a love theme introduced in the film’s opening city scene. It presages the relationship even before we’ve been introduced to the characters. The second theme underscores Therèse’s fascination with Carol. Says Burwell, “This is basically a cloud of piano notes, not unlike the clouded glass through which Todd Haynes and Ed Lachman occasionally shoot the characters.” The third theme captures the characters’ sense of loss when they are separated. Knowing that Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara would convey the characters’ pain in their performances, Burwell opted instead to use open harmonies (fourths, fifths, and ninths) to communicate their sense of emptiness.

Burwell orchestrated the music for chamber-size ensembles to maintain the sense of intimacy between the characters. Some cues feature as few as four instruments while others were performed by as many as 17 musicians.

Burwell’s spare, modest score is a departure from the style Haynes explored in his previous foray into this territory: his Douglas Sirk homage, Far From Heaven (2002). Elmer Bernstein’s score for that film was lush and emotionally expansive, aping Frank Skinner’s musical stylings in films like Magnificent Obsession (1954) and All That Heaven Allows (1955). Burwell wrote only 38 minutes of music. Yet it all is beautifully attuned to the film’s mood of quiet desperation.

Thomas Newman earned his thirteenth nomination for Bridge of Spies. (Insert Susan Lucci joke here.) Newman, of course, descends from film composing royalty as the son of the renowned classical Hollywood tuner, Alfred Newman. Yet, despite Newman the Younger’s distinguished career in Tinseltown, Newman the Younger has a long way to go to catch his pops. Alfred won nine Oscars and accrued more than forty nominations.

Newman’s music has graced some of the most beloved American films of the past three decades, such as The Shawshank Redemption, American Beauty, Finding Nemo, and Wall-E. Although he is known for his versatility, an NPR story on his score for Bridge of Spies notes that Newman has become known for passages that incorporate “quirky, layered piano writing and jagged string motifs.”

Newman and Spielberg save the score’s biggest moments for the film’s climax and epilogue. Indeed, more than half of the film’s score is backloaded into its last three cues, which together account for about 25 minutes of music. Displaying Newman’s full emotional range, “Glienicke Bridge” anxiously underscores the tense prisoner exchange that delivers Rudolf Abel back into Soviet hands. “Homecoming” features solo trumpet and oboe to convey James B. Donovan’s sense of validation now that his fellow commuters’ scowls of disapproval have turned to smiles of patriotic pride.

Newman’s score for Bridge of Spies is a very solid piece of work evincing the craft and refinement displayed by earlier masters like Jerry Goldsmith and John Barry. Yet the music’s modesty and conventionality make it the kind of score all too easy to overlook.

The Legends: John Williams and Ennio Morricone

Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015).

Oddsmakers have tabbed our final two nominees, John Williams and Ennio Morricone, as the most likely to take home the big prize. The former is nominated for Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the seventh film in George Lucas’s series and the seventh scored by Williams. Coming 48 years after the composer’s Oscar win for the first Star Wars film, Williams’s music updates the neo-Romantic style he helped to revive in the 1970s. It also adds new themes for key new characters, such as Rey and Kylo Ren.

Williams wrote a massive amount of music for The Force Awakens. (Indeed, the 102-minute score is more than double that of Newman’s score for Bridge of Spies.) But very little of it simply replicates materials from the previous films. By Williams’s own count, only seven minutes of the score function as “obligatory” references to his own immediately recognizable themes.

As in his previous work, Williams shows enormous skill in juggling the various leitmotifs that are attached to the film’s dramatic personae, often moving a motif through different instrument combinations in order to vary the color and timbre of each cue. And Williams’s sure touch with this material undoubtedly enhances J.J. Abrams’ everything-old-is-new-again approach to The Force Awakens, a strategy that seems to have satisfied long-time fans, many of whom probably have dusty old compact discs of the composer’s earlier Star Wars scores.

The score for The Force Awakens earned Williams’s his fiftieth nomination and it is a fine addition to his already considerable oeuvre. Still, considering that Williams has won Oscars on five previous occasions and the been-there- done-that aspect of the enterprise, it is hard to believe that this score will bring the composer his sixth statuette. Thankfully for him, Williams’s reputation as one of the greatest composers to work in the film medium is already firmly secured.

That leaves just Ennio Morricone, the equally legendary Italian composer whose collaborations with Sergio Leone redefined the sound of the Western. Nearly fifty years after Morricone’s theme from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly topped U.S. record charts, Morricone garnered his sixth Best Original Score nomination for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight.

The film marked Morricone’s return to the genre after several decades of avoiding it. According to the composer, most directors who approached him simply wanted him to replicate the sound of his great Spaghetti Western scores. Morricone preferred to pursue projects that let him stretch in other directions.

Tarantino gave the Maestro a free hand in developing the score of The Hateful Eight, and Morricone responded with one of his best scores in decades. Aside from his characteristic use of vocal chants as rhythmic accents, the score for The Hateful Eight largely avoids the sort of psychedelic touches and extravagant tone colors found in his Spaghetti Western scores. Gone are the electric guitar, ocarina, whistles, and coyote yelps that established Morricone as a kind of musical meme. Substituted instead are much more conventional orchestral colors with the strings and wind sections taking prominent roles in The Hateful Eight.

Perhaps one reason for this move back to classical Hollywood convention is due to the hybrid qualities of Tarantino’s story. As Peter Debruge noted in his Variety review, The Hateful Eight is “a salty hothouse whodunit that owes as much to Agatha Christie as it does to Anthony Mann.” Morricone himself seems to concur. In an interview with Rolling Stone, the composer added, “Quentin Tarantino considers this film a Western; for me, this is not a Western. I wanted to do something that was totally different from any Western music I had composed in the past.”

Morricone’s score has a “theme and variations” structure that shows him adeptly changing his tempo, texture, and instrumentation to adapt his main theme to new dramatic contexts. His Overture provides the basic template for the score. The low strings and winds play a sustained minor chord that sneaks into the soundtrack. After a few seconds, the upper voices enter playing chords on the first and third beats of each measure to outline the basic harmonic progression of the main theme. Eventually an oboe will enter playing a repeated interval as a counterrhythm over the top of this pattern.

This gives way to the strings, which intone a serpentine diatonic melody that provides the spine for the rest of the cue. Gradually, Morricone introduces more instruments, such as vibes and brass, to vary the tone color and even adds a simple bridge section that consists of a series of soft, chromatically descending chords. After a brief restatement of the main melody, the cue finishes with a series of long sustained chords marked by shifting harmonies in the inner voices. The clarinet plays a fragment of the main theme before it eventually fades out. The cue never comes to the kind of climax that a traditional cadential structure would provide. Instead it simply unwinds itself.

The central theme is probably given its most elaborate treatment in the main title, “L’Ultima Diligenza di Red Rock – Version Integrale.” A steady timpani pulse and a sustained pitch in the strings provide a pedal tone against which a new melody is introduced in the contrabassoon’s low register. This musical figure has a serpentine quality like the other, and it has been written to function as counterpoint to its predecessor at later moments when the two will be interleaved. Morricone gradually introduces more instruments to thicken the texture and even adds brass and pizzicato accents as embroidery atop the main theme. A hi-hat cymbal adds some rhythmic variety to the basic pulse of the timpani.

After a brief detour into some transitional material, the main melody returns, but now played by strings, xylophone, and muted brass instruments. The main musical figure continues to be restated with new ideas simply piled on top. As the music grows in both volume and intensity, Morricone adds trills and furious agitato string runs to create a cacophonous, but organized musical chaos. The cue climaxes with the melody played fortissimo in octaves by the violin section, soaring toward a sudden and abrupt stop. After a short pause, the contrabassoon quietly returns to play a brief musical coda that eventually fades to silence.

Morricone has long been a master of this type of musical structure. He’ll start with a simple musical idea, but then adds different countermelodies or obbligatos to vary its mood and tone. The ongoing accretion of elements creates the effect of a long crescendo that eventually finds release in silence. (For an earlier example of this kind of technique, see his cue for “The Desert” on The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly soundtrack.)

Beyond its purely musical effectiveness, though, “L’Ultima Diligenza di Red Rock” exudes a roiling tumult that fittingly captures the sense of deception and distrust that will pervade Minnie’s Haberdashery. The musical mood remains mostly dark and ominous throughout, leavened only by the bright solo trumpet fanfare that underscores Sheriff Chris Mannix’s reading of Major Warren’s Lincoln letter.

Tarantino’s trust in the Maestro was amply rewarded. This is a score that no one but Morricone could produce. As was the case with Jóhann Jóhannsson’s score for Sicario, it seems to be the best thing about The Hateful Eight. Tarantino wanted a soundtrack album for one of his own films that he could proudly place alongside other Morricone albums in his collection. He got it and then some.

Prediction: The Maestro finally gets his due! Although Morricone received an honorary Oscar in 2007 for his “magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the art of film music,” none of his individual scores have received awards from the Academy. I expect that to change next Sunday night. In fact, betting odds put Morricone’s chances of winning an Oscar for Best Original Score at 1 to 5. That means that a five dollar bet will net you one dollar profit if you win. That is about as close to a sure thing as you are likely to find in the gambling world. And even I’m not dumb enough to buck that trend.

In truth, I would be happy to see any of these composers take home the Oscar. I’ve enjoyed their contributions to the art of film music for much of my adult life. But, for me, the only real question is this: How long will the standing ovation be as Ennio Morricone prepares to give his acceptance speech? I put the over/under at 65 seconds.

Variety offers overviews of the nominees for Best Original Song here and Best Original Score here. Both pieces include comments from the composers and songwriters competing for this year’s awards.

You can find interviews with nearly all of the nominees for Best Original Score: Morricone, Williams (here and here), Newman, and Johannsson. Carter Burwell’s notes on Carol can be found on his website.

Emilio Audissino’s book on John Williams offers a terrific overview of the composer’s career. For a study of Morricone’s compositional techniques and style, see Charles Leinberger’s monograph on The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly in Scarecrow Press’s series of Film Score Guides. My book The Sounds of Commerce includes a chapter on Morricone’s spaghetti western scores.

More on Morricone: The Maestro weighs in on the film scoring process in Composing for the Cinema: Theory and Practice of Music in Film, which is coauthored with Sergio Miceli. You can listen to the opening cue of the score for The Hateful Eight here.

P.S. 25 February 2016: Thanks to Peter Brandon for a correction concerning the Canadian identity of The Weeknd, Quenneville, and Belly.

LONDON, ENGLAND – DECEMBER 08: Composer Ennio Morricone is seen during a Live Recording for the H8ful Eight Soundtrack at Abbey Road Studios on December 8, 2015 in London, England. (Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Universal Music)

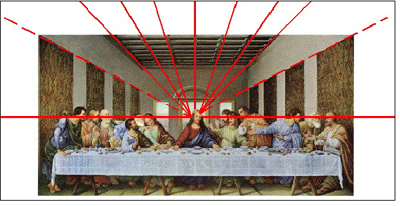

Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom

From Mad Max: Center Framed, by Vashi Nedomansky.

DB here:

If you’re a filmmaker, how do you frame the action you’re shooting? Put aside documentary shooting, which doesn’t allow you as many options as staged filming does. A lot of your compositional decisions depend on the aspect ratio of the image.

After the mid-1910s, filmmakers relied heavily on close views—framing typically two or three people, or even just one. These “portrait” framings were well-suited to the 4:3 format that was standardized in the silent era. But what happens when filmmakers must compose in wider frames, especially the 2.35:1 format that became common with CinemaScope?

Too much scope in ‘Scope?

In classic Western painting and other traditions as well, a horizontal format is associated with fairly distant views of groups or landscapes.

Early ‘Scope filmmakers did sometimes favor distant, spread-out ensemble staging, with greater or less depth. (Below: Island in the Sun; Bad Day at Black Rock.)

I try to track some of those early options in this online lecture.

But as technology improved, filmmakers managed to shoot medium- and close shots in the wide format. They “tamed” ‘Scope to a more traditional continuity. And as there were pressures toward “intensified continuity,” filmmakers adapted those tenets to ‘Scope. They gave us close-ups, fast cutting, and roaming camera movements within the widescreen array.

Like all solutions, this involved trade-offs. The 4:3 format was well-suited to the human body, and even a tight facial close-up could fill it fairly well. But a single or even a two-shot, in anamorphic widescreen, can leave a lot of the frame vacant or relatively unimportant.

Cinematographer Boris Kaufman objected to the extra real estate. In traditional arts, the design should fit snugly into the format, with all areas contributing to the image’s effect:

The space within the frame should be entirely used up in composition.

But close views in widescreen typically leave a lot of dead space. If you put the figure in the center, that dead space can be on the sides.

The bilateral symmetry of Wes Anderson’s frames is achieved on the premise that the figure is facing straight out at the viewer, so Anderson has the problem of filling up the flanking areas.

Or the dead space can be bigger on one side of the frame than the other. In that case, the figure, even a close one, is placed off-center in the 2.35/2.40 frame. This can suggest that the object of attention is somewhere beyond the empty zone.

To avoid sheer dead space, you can try to settle something in the background. If it’s dramatically important, you can generate some nice compositional tension, in the manner of the wide-angle, deep-focus look of the 1940s.

So as with most creative options, making a choice involves (a) tradeoffs and (b) further choices, some of them fairly forced. Go with widescreen, and you have to fill the frame somehow. Make one choice, and you have some dead areas, but you can control the viewer’s attention. If you fill the areas with significant action, you need to find some dynamic compositions. But you divide the viewer’s attention. You now have to make people look where you want and when you want.

Cuts for composition

Now add in cutting. How do you cut widescreen shots together, say in a conversation scene?

Go back to painting. Sometimes the most important item sits in the geometrical center of the picture format. Rudolf Arnheim points out that often the exact center is vacant and items are grouped around it. The result is a pictorial tension, with elements balanced, either symmetrically or in more complex patterns. In Bruegel’s Fall of Icarus, the major action is split–a dramatic splashdown, a world that doesn’t notice. The fall takes place somewhat off right of center, in a bright but far-offf area. It’s still almost indiscernible. The indifference of the peasants is given in the very composition of the image.

So too with cinema. In a single image, when the main point of interest isn’t dead center, there can be either symmetry, or important items grouped around the center.

Going beyond the single image, we find that editing can create a fairly gentle seesawing around the central area. A common tactic is shot/ reverse-shot, with over-the-shoulder framings. In widescreen, that option tends to make the center fairly empty.

Or you can try “compensatory” shot/ reverse-shot cutting, so that the empty area of the first shot is filled by the corresponding figure or action in the next shot.

This second isn’t a bad solution, since the two shots together satisfy Kaufman’s dictum in a roundabout way. They become a “cinematic” way of filling the horizontal format, but in time rather than purely in space. And in this instance the main characters’ angled eye levels fit together snugly, in the upper center.

There can be a certain suspense added, as the second frame slowly fills up to reveal the item. When Furiosa looks off right, we cut to a shot of what’s caught her attention–an attack vehicle drawing into the frame on the right.

Assume, as most people do, that our attention fastens on certain aspects of the frame—typically those that attract us perceptually (brightness, movement, color, sound source, etc.) and that provide ongoing story information. So now you have to consider: How closely do you want your second shot to pick up on the crucial area of the first shot? That is, is the smoothest cut the one that starts the next shot with the viewer’s eye in the same part of the frame?

Some editors argue for this sort of continuity. “If the eye is led to one side of the screen,” notes one primer, “the action of character in the next shot might be located on that side also. Again, the purpose of the cut is to allow the eye to follow the movement.”

We’re back with our old friend the guided saccades, the fast, jerky eye movements that sample our environment. We’ve seen saccades at work in a single shot, thanks to staging that guides our attention. (Go here for a first-pass analysis, here for the eye-tracking evidence.) What about the cuts? The research of psychologist Tim Smith suggests that many editors intuitively try to match the point of interest across cuts. This is especially evident in the default zone, the geometrical center.

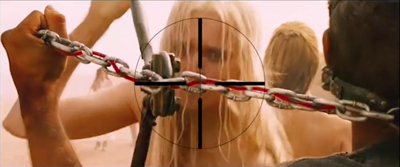

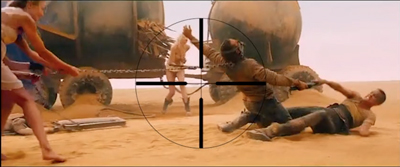

Keeping the viewer’s attention fastened on one area of the screen across the cut could be of great value in fast-cut action scenes. That way the viewer couldn’t miss the most important thing—a face, a gesture, a prop. This was the aim of George Miller in certain scenes of Mad Max: Fury Road. According to cinematographer John Seale, the centered compositions make it easier for the viewer to follow the action.

Your eye won’t have to shift…to find the next subject when you’ve only got 1.8 seconds of time to do that.

Vashi Nedomansky has created a striking video, complete with centered crosshairs, that shows the strictness of framing and composition during one action scene. Both long shots and fairly close ones are center-framed.

Vashi notes that Michael Bay and other directors seem to rely on fast cutting without due concern for where the viewer’s eye lands at the end of each shot. Combined with very short shots, compositional confusion can flummox us. We don’t know where we should be looking.

Miller uses a greater variety of compositions in other stretches of the film, as my illustrations above indicate. At times he applies his “matching zone system” to more off-center layouts. Furiosa is shown waiting for the biker gang to complete the deal, and she’s center framed.

We cut to one biker surveying the scene. He (she?) is positioned off-center, so that we get a certain foreground/background dynamic between him (her?) and the truck far in the background. Now cut to Furiosa, who’s now in the same area of her frame; the empty space on the left seems to confirm what her eyeline suggested about the biker’s position above the canyon. (Interestingly, Miller slightly breaks the axis of action to get this smooth graphic cut.)

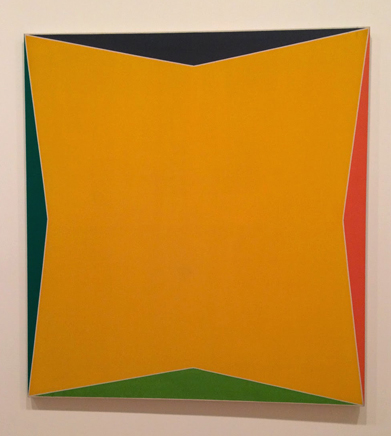

Still, you can argue that for fast-cut scenes it’s better to adopt a brute-force simplicity of composition, favoring the center. (While of course assuming that ordinary continuity principles, such as matching of movement, screen direction, eyelines, and so on, are obeyed.) Tim Smith’s experiments have shown that all other things being equal, our eyes drift to the center of the format from shot to shot–a point that Arnheim also makes about “the power of the center” in all images. This visual habit is challenged by so-called empty-center painting of the 1960s and 1970s, as seen in Kenneth Noland’s Shadow on the Earth and Larry Zox’s Decorah.

Mad Max: Fury Road seems to me a superbly directed film in its chosen style, but we can find alternatives. What about fast cutting that tries, as a part of an action scene’s kinetic drive, to shuttle or bounce the viewer’s attention more widely across the frame? This option wouldn’t be helter-skelter in the Bay manner; it’s calculated, and engenders its own pictorial excitement.

Not exactly a picture scroll, but kind of

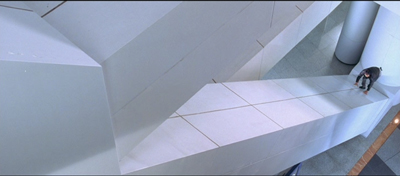

We can find many examples in the Asian action tradition. Take for example one of the extended pursuits in Benny Chan’s New Police Story, a 2004 Jackie Chan vehicle. Jackie is clambering up along an angled beam of the Hong Kong Convention Center, and the framing puts him far to the right, emphasizing the distance and steepness of the climb.

As he scrambles up, he seems not to notice that his pistol falls out of his pocket. But we do, because it stands out against the pale cladding as it slides down to the bottom of the slope. Miller would have given us a separate, centered shot of this crucial action, but here it becomes an instance of that “gradation of emphasis” that widescreen encourages.

Before Jackie can hit frame center, there’s a cut that reverses the design of the first shot. A low angle puts him at the far left corner of the frame as he reaches the top. We never really see Jackie in the center of the frame in either shot.

The two shots are cut fast (about 3 seconds each), but there’s no problem grasping the action. Hong Kong filmmakers realized that you could cut long shots quickly if the composition and lines of movement were very clear. There is, it turns out, enough time for the eye to catch up to the main point of the composition, but it does ask us to exercise.

A more percussive cut comes when Frank, also unarmed, searches out Joe, the gang leader, in a toy department. A snap-movement of the kind HK filmmakers love shows an off-center empty slot; Frank pops in from screen right.

Cut to Joe stalking Frank, seen in another slot. It’s an optical POV shot, but it’s also off-center, balancing the composition of the first shot. A cut back to Frank closes the POV pattern. Perhaps the oscillation around the frame center can prime us for the next shot.

To get a sense of this “all-over” frame composition, have a look at this sequence from Yuen Kwai’s Ninja in the Dragon’s Den (1982). The combat swiftly passes from the center to the sides or to a corner. Thanks partly to the architecture of the cabin and the mill wheel, and partly to the judicious framing, there’s a sense that Kaufman might be satisfied that the space in the frame is “entirely used up”–not in a single shot, but in the totality of shots. (I’ve left in the English dubbing so subtitles don’t distract your eye.)

Hong Kong filmmakers mastered dynamic compositions during fights, but they were seldom as eccentric as their Japanese colleagues. Once anamorphic widescreen became common in Japan, directors pushed points of interest to frame edges and exploited unusual framing.

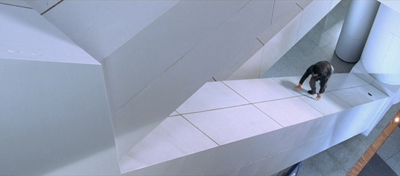

Consider the shootout at the climax of Suzuki Seijin’s Underworld Beauty (1958). A gang has trapped the protagonist Miyamoto and a young woman in a boiler room and is subjecting them to some heavy ordnance. In one series of shots, we see a gunman fire to the right, and as a result of his strafing, one boiler starts to blow.

The progression of boiler shots shifts us more or less rightward across the basement, and the empty area on the far left of shot 3 suggests that the gunman remains offscreen in the upper left. Now we get a sort of establishing shot showing the two boilers of shot 2 more fully.

I think we’re inclined to place the offscreen gunman still in the upper left. The spraying boiler we’ve seen is now on frame left. What’s surprising is that Miyamoto and the woman are crouching way down in the lower right corner. As you watch the shot, you might not notice them at first, but Suzuki has them change position after a moment so their movement attracts our eye. In addition, the shot is fairly prolonged as the boss calls out to his prey, so viewers have time to discover them. This is, I think you’ll agree, a pretty bold use of the anamorphic frame.

Once we’ve noticed them, how does Suzuki cut closer to the couple? Unpredictably.

I feel a bump here every time I see it, because it’s hard to read the facial expressions from this angle. Instead, we get an almost abstract composition spread in a diagonal across the frame. Again, the geometrical center is less important than the shapes, edges, and tones that cross it.

At last we get something like an orthodox framing of the couple, eased by a match on action as the woman tips her head.

So the passage ends with a center-framed image. As often happens, decentering registers as an accent, a transitory departure from the baseline, the centered image. Not only will most action pass through the center, but we can be yanked to other regions in confidence that we’ll eventually return to it.

The shots in Underworld Beauty aren’t especially fast-cut, but I’ll close with another extract that is. This is the opening of Baby Cart at the River Styx (in the Lone Wolf and Cub series; dir. Misumi Kenji, 1972). Again, I’ve disabled the subtitles. (NB: Probably not best for children to see this.)

In a burst of shots, we get centered images, off-center ones, and radically off-center ones.

Continuity rules are respected and the camera is angled properly; but the compositions bounce from perfectly readable to perversely indiscernible. Some shots keep us in suspense about what’s about to happen, yet at no point is the action unclear. Again, the impact comes partly from simply composed, but highly varied, images.

George Miller’s strict target-framing is very powerful, but there are other options, even in fast-cut sequences. The idea of leading our attention across areas of the screen goes back to Eisenstein, the theorist-director who enjoyed zigzag graphic designs and the pictorial clatter created by a cut. One lesson: Every bit of the frame can be used, if only to jolt the viewer’s eye. All the action on the screen isn’t just in the story.

My quotation from Boris Kaufman is taken from Edward L. de Laurot and Jonas Mekas, “An Interview With Boris Kaufman,” Film Culture 1, no. 4 (Summer 1955): 5. The quotation about matching screen zones comes from Steven E. Browne, Video Editing: A Postproduction Primer, 3d ed. (Focal Press, 1997), 147. Bruce Block discusses “affinity continuums” from shot to shot in Chapter 7 of The Visual Story: Seeing the Structure of Film, TV and New Media, 2d ed. (Focal Press, 2013).

The Rudolf Arnheim book I’ve mentioned is The Power of the Center: A Study of Composition in the Visual Arts: The New Version (University of California Press, 1988). “Empty-center” painting is discussed by Thomas B. Hess in the essay of that title in New York (2 April 1973), 64-65 and in “Olitsky without Flattery,” New York (1 October 1973), 76-77. Hess describes paintings in which “the picture plane is stretched like a trampoline, with lots of spring action at its quivering edges.”

Tim Smith’s eye-tracking research is relevant to the framing principles I’ve been considering. Although he has yet to consider the more complicated cases of dispersed points of attention, he has found strong evidence that the default area remains the geometrical center of the screen. See his “Watching You Watch Movies: Using Eye Tracking to Inform Cognitive Film Theory,” in Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies, ed. Arthur P. Shimamura (Oxford, 22013), 170-171; the relevant video, with a heatmap of viewers’ attention, is here. Tim’s website is full of other examples from his research. Thanks to Tim for correspondence on this point.

Thanks also to Patrick Keating for email discussion of some of these matters.

I discuss principles of early widescreen shooting and staging in the online chapter “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses.” See also the video lecture of the same name. For another example of radical decentering during a fast-cut combat, though put to different uses than in the Japanese examples here, see my entry on a King Hu jump cut.

Incidentally, we might wonder whether the centered compositions in Mad Max: Fury Road aren’t also acknowledging that on some displays (cable, streaming, airlines) these images will be cropped. To put important material too close to the frame edge risks losing it on downstream platforms. See “Filling the Box: The Never-Ending Pan-and-Scan Story.”

Ninja in the Dragon’s Den.

P.S. 1 March 2016: There’s a sequel to this entry here.

Rotterdam supports Busan International Film Festival

DB here:

An entry earlier this week noted Tony Rayns’ open letter criticized the attack on Busan’s Lee Yongkwan. Now staff and industry professionals at the Rotterdam Film Festival have gone on the record with their support. Full details at the BIFF site.

FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

DB here:

Forty years ago, Kristin and I signed a contract with Addison-Wesley publishers to write Film Art: An Introduction. The first edition, a squarish item with a butterscotch-brown cover, was published in 1979. Like most textbook authors, we had to assign all rights to the publisher. Addison-Wesley sold our book to Knopf, which produced a second edition in 1985. Then the book was acquired by McGraw-Hill. McGraw-Hill published the subsequent nine editions, from 1990 onward.

Last week, Kristin and I and our new collaborator Jeff Smith received our copies of the eleventh edition. It looks very good and we think it’s our best effort yet. By chance, we learned at the same time that Film Art, in all its editions, currently ranks as 153 in books assigned in American college courses (based on a sample of nearly a million syllabi). No other film textbook appears in the top 400 titles. Back in the 1970s we never imagined such success.

FA 11e contains many new features, which I’ll talk about shortly. But I’d also like to say some things about the book’s perspective on cinema. I’ve discussed the conceptual side of our approach in an entry devoted to the previous edition.

But since concepts don’t arise from nothing, I thought I’d wax a little personal and talk about how Film Art has reflected my developing ideas about movies. Readers wanting the meat-and-potato information about the new edition can skip down to the section, “Humblebragging, minus the humble part.”

A bookish movie wonk

I came to movies through books. I must have been fourteen or fifteen when I read Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957). It was the first grown-up book that I thought I completely understood. Soon after I read Rudolf Arnheim’s Film As Art (1957), which I knew I did not completely understand. But those two books became my guides to what films to see and what ideas to think about.

I came to movies through books. I must have been fourteen or fifteen when I read Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957). It was the first grown-up book that I thought I completely understood. Soon after I read Rudolf Arnheim’s Film As Art (1957), which I knew I did not completely understand. But those two books became my guides to what films to see and what ideas to think about.

Living on a farm, I was somewhat isolated, but I did see Hollywood classics on television, and I could occasionally catch current releases at theatres in nearby towns, notably Rochester, NY. With the aid of Andrew Sarris’s “American Directors” issue of Film Culture and some issues of Movie (UK), my high-school years became devoted, in part, to film.

During the 1960s, interest in film exploded. Europe’s “young cinemas” like the French New Wave came to prominence. Hollywood films became edgier. High-tone magazines began to pay attention. This was the era in which James Agee, Parker Tyler, and Manny Farber gained somewhat delayed fame as critics. (I talk about this development in my Rhapsodes book.) Cahiers du cinema became known outside France, and American critics like Sarris and Pauline Kael became artworld celebrities.

In the same era there came a burst of film-appreciation books. They weren’t textbooks per se, but they were often used in the film courses that were springing up across the country. Among those books were Ernest Lindgren’s The Art of the Film (rev. ed., 1963), Ivor Montagu’s Film World (1964), and Ralph Stephenson and J. R. Debrix’s The Cinema as Art (1965). I was drawn to the idea of a general account of the possibilities of film as an art form, so these books, followed by V. F. Perkins’ contrarian Film as Film (1972), appealed to me. I later realized that they belonged to a genre that stretched back to the 1920s and included extraordinary contributions like Renato May’s Linguaggio del Film (1947). Still further back, they, like all texts, owe a debt to Aristotle’s Poetics and Renaissance treatises on the visual arts.

Throughout my college years, I thought that the core activity of film culture was criticism: the effort to know a movie as intimately as possible. That’s still a widely-held view. In graduate school at the University of Iowa, my horizons expanded, as I was exposed to film history, though not through much primary research, and film theory, which was just starting to be a major wing of academic cinema studies. My dissertation was on French Impressionist silent cinema, what’s come to be called the “commercial avant-garde.” I wrote it because I wanted, ultimately, to understand the context around Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, but for the project I concentrated on directors like Gance, L’Herbier, Epstein, Dulac, and Delluc. The thesis had three parts: one on the historical context, one on Impressionist theory, and one analyzing the films. This mixed approach has become a common one for me. I still think that a movie will sit at the center of my interest, but I’m attracted to questions that cut across criticism/history/theory boundaries.

Throughout my college years, I thought that the core activity of film culture was criticism: the effort to know a movie as intimately as possible. That’s still a widely-held view. In graduate school at the University of Iowa, my horizons expanded, as I was exposed to film history, though not through much primary research, and film theory, which was just starting to be a major wing of academic cinema studies. My dissertation was on French Impressionist silent cinema, what’s come to be called the “commercial avant-garde.” I wrote it because I wanted, ultimately, to understand the context around Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, but for the project I concentrated on directors like Gance, L’Herbier, Epstein, Dulac, and Delluc. The thesis had three parts: one on the historical context, one on Impressionist theory, and one analyzing the films. This mixed approach has become a common one for me. I still think that a movie will sit at the center of my interest, but I’m attracted to questions that cut across criticism/history/theory boundaries.

Before the 1970s, most college film courses were organized historically, running from Lumière/Méliès/Porter to Neorealism. (Arthur Knight again.) But there was emerging a different sort of course, one that surveyed “the language of film” conceptually. Just as an introduction to music would lay out basic categories like melody, harmony, rhythm, and form, so film courses—in the manner of the aesthetics surveys I mentioned—would try to isolate the basic elements of cinema. This new orientation was probably also inflected by semiotics, then becoming a hot topic in grad-school circles.

When I came to UW—Madison in 1973, ABD and eager to work, I was given the basic survey course, Introduction to Film. It enrolled about 400 students a semester and was held in a gigantic classroom; from the stage I could barely see the students in the back. (There were a lot of them back there, for reasons we now understand.) I had four stalwart teaching assistants: James Benning, Douglas Gomery, Brian Rose, and Frank Scheide, all of whom have gone on to fame. Learning as much from them as they did from me, I organized the course as a survey of film form and style. That overall structure was the first rough cast of Film Art.

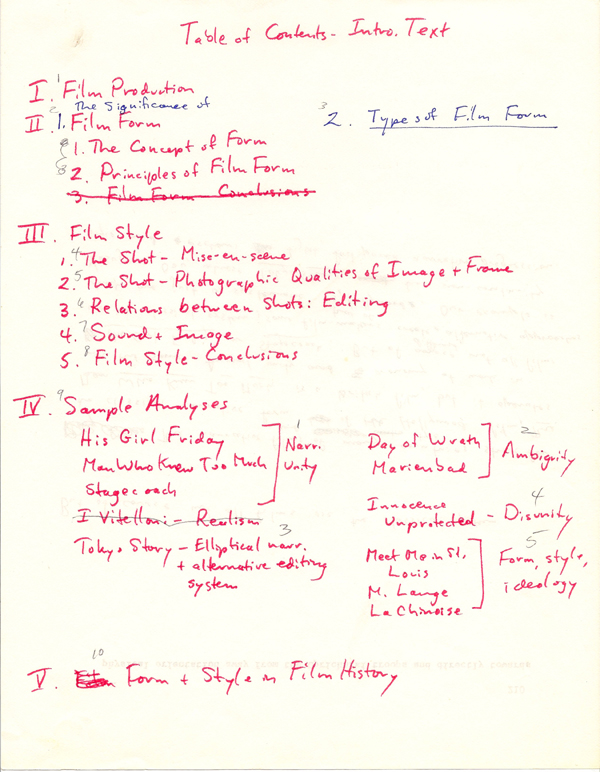

By this time there were several books designed as textbooks for such an appreciation course. After reading a few I decided not to use any. I relied on Perkins’ Film as Film, Noël Burch’s Theory of Film Practice, Jim Naremore’s excellent monograph on Psycho, and photocopies of essays by Bazin and others. After teaching the course for three years, I decided, at the suggestion of the Addison-Wesley editor Pokey Gardner, to propose it as a textbook. Kristin had by then taught the Intro course with me, had published some articles, and was working on stylistic analysis for her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible. She became my coauthor, beginning what some have called America’s longest study date.

From treatise to textbook—and back again?

Although we wrote it for the textbook market, I didn’t think of it as a textbook. With the hubris of a twentysomething, I thought of it as my treatise on film aesthetics. I wanted it to be as comprehensive as I could make it.

As Perkins pointed out, most books on film aesthetics were tied to the idea of the silent film as the pinnacle of film art. Editing was conceived as the supreme film technique, and Griffith and Eisenstein were presented as paragons. Admiring both of them and silent film as a whole, Kristin and I wanted nonetheless to give decent weight to “the Bazinian alternative”: long takes, camera movements, staging, and cinematography in depth were no less significant artistic resources. Color, sound, widescreen, and other resources were often ignored by the older tradition, but they had to be given their due. (At this point Play Time became a touchstone for us. It still is.) Burch’s book was particularly important as a quasi-structuralist revision of Bazinian ideas; I found, and still find, this book inspiring.

Just as important, I thought, was a need to situate techniques of the medium in a holistic context. While I was pursuing DIY film studies down on the farm, I was also reading modern literature and the New Criticism that then dominated literary life. For me, The Context Of The Work was everything. The whole would always nourish whatever technical tactic or local effect we might pick out.

Many textbooks still insist that techniques have localized meanings: a high angle means that the subject is diminished and powerless. Yeah, except when it doesn’t, as we insisted about this shot from North by Northwest in the first edition and since. (“I think that this is a matter best disposed of from a great height.”)

Because I was interested in the whole film, I was attracted to philosophers of art who balanced a recognition of style with a recognition of overall form. Thomas H. Munro’s Form and Style in the Arts (1970) helped me with this, but the major influence was Monroe Beardsley’s Aesthetics (1958), with its distinction between texture and structure. That distinction meant realizing that films displayed large-scale formal principles, like sonata form in music. What were those principles?

Hence a chapter on narrative and non-narrative forms. We developed ideas of narrative out of formalist and structuralist theories. In the first edition, there was a lot more on narrative than on other sorts. In later editions, we tried to flesh out some genuine non-narrative options: abstract form (Ballet Mécanique and many experimental films); categorical form (e.g., Gap-Toothed Women, The Falls); rhetorical form (e.g., The River, Why We Fight); and associational form (e.g., A Movie, Koyaanisqatsi, and many “film lyrics”).

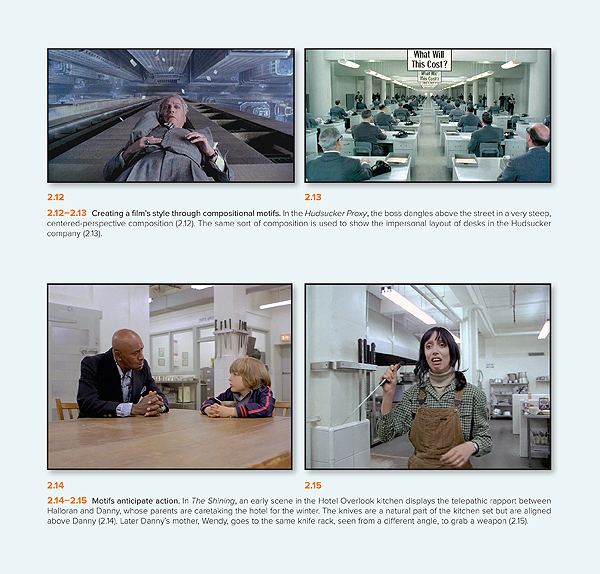

In teaching Introduction to Film, I noticed that many students hadn’t been exposed to basic aesthetic concepts like form, style, theme, subject matter, motifs, parallels, and the like. The old New Critic in me rose up. I thought these ideas and terms, being central to the aesthetics of any medium, needed to be in the book too. Hence a chapter “The Significance of Film Form.” (Above is a page illustrating visual motifs: perspective design, props set up to be used later.) Some have taken this chapter as a manifesto of a “formalist” perspective, but actually the ideas in the chapter are ingredient to any aesthetic position whatsoever. Every analyst will trace patterns of development in a film, or weight the opening strongly, or notice thematic parallels. These are basic tools for thinking and talking about any art.

But I wasn’t a New Critic 100%. I’ve always been interested in going beyond the artwork itself to look at the artistic traditions and institutions behind it. Because a film results from a concrete process of production, I thought it important to include a chapter on how a movie gets made. That topic was the first one in our introductory course; the reading was Truffaut’s “Journal of Fahrenheit 451.” Starting Film Art with a chapter on production served to introduce film techniques in a concrete context, and it showed how what appeared on the screen was the result of choices among alternatives. We thought, and still think, that this chapter might engage students who want to pursue filmmaking themselves. It’s been gratifying to learn that some production courses use the book.

The concern for practice led us to specify, for the first time in an introductory studies text, the 180-degree system of editing, the four basic dimensions of film editing, a layout of what you can do with sound in relation to space and time, and other practice-based concepts. We tried to systematize what filmmakers do, however intuitively. Sometimes we popularized terms that were already specialized (e.g., “diegesis” for the world of a story). Sometimes we had to invent terms for things that didn’t have names (e.g., the graphic match in editing). Sometimes we had to pick one usage of a term that was used in several ways (e.g., jump cut). Sometimes we had to make distinctions that weren’t explicit in the literature, such as the difference between story and plot, or deep-space staging and deep-focus cinematography.

Creating such labels may seem pedantic, but once we have a name for something we can notice it. Kristin and I believed that a study of film aesthetics has to be alive to all creative possibilities we can imagine. For example, in probably the toughest part of the book, we sought to account for all the possible creative choices involved in relating sound to narrative time. Maybe some options are rare, but they do exist as part of cinema, and they may yield powerful effects.

Aesthetics in history

Beetlejuice.

Other features of the book flowed from these central ideas. Because of the emphasis on holism, we added sample analyses as well—studies of single films that showed how the various techniques worked together with overall form. The urge to be comprehensive led us to devote more space to experimental, documentary, and animated film than was common in introductory textbooks. And, since this was a period in which academic film studies was making important discoveries, Kristin and I thought it important to discuss the concept of the “classical Hollywood cinema,” a powerful tradition of story and style that students would have often encountered. By the time Film Art 1e was published, we were planning what would become The Classical Hollywood Cinema, written with Janet Staiger.

So Film Art became a treatise. Was it a textbook? I wasn’t sure. I thought the publisher might turn it down. Even though it incorporated examples that were student-friendly, it had a daunting infrastructure. I thought faculty might find it too complex for most classes. Had it been rejected, I would probably have tried to publish it as a free-standing book like those 1960s treatises.

Surprisingly, all these features of the book were acceptable to the readers to whom Addison-Wesley sent the manuscript. Still, many had a big objection: There was no chapter on film history, and that would kill it for them.

I hadn’t included a historical unit in my introductory course because there wasn’t time. Besides, our department had a parallel course surveying film history. But Kristin and I were happy to accede to the readers’ request. We took as the chapter’s motto a line from art historian Heinrich Wölfflin: “Not everything is possible at all times.” (You see what I mean about complexity; what film textbook quotes Wölfflin?) The sentence simply means that the artist, in this case the filmmaker, inherits a limited set of possibilities of form and style, to which she can respond in a wide but not infinite variety of ways. We (mostly Kristin) used the concepts we’d developed in the book to trace a series of major traditions and schools, from early cinema through to the French New Wave. We’ve since enhanced that account, bringing it up to date with the New Hollywood and Hong Kong film, and accentuating the continuing importance of older trends–signalling, for instance, German Expressionism’s legacy in horror comedies like Beetlejuice, above.

We know that we owe a lot to luck of timing—to being at the start of academic film studies—and to the many, many teachers who have offered us suggestions for improving the book. One advantage of doing a textbook is that you can improve it incrementally, something not possible with a scholarly book that will probably see only one edition.

We’re gratified that the result has continued to be useful. We continue to meet teachers and students who tell us they’ve benefited from it. Filmmakers, too, from Pixar artists to experimentalists. The book has been given a couple of dozen translations. Other textbook writers have found our concepts, organization, terms, and examples persuasive. (When I see how closely some hew to our book, I don’t know whether to feel gratified or depressed.) We take this wide acceptance as a sign that we contributed something fresh and valid to our understanding of cinema. Maybe we did write a general aesthetic treatise after all—not the first, not the last, but one that remains illuminating and in some respects foundational.

Humblebragging, minus the humble part

From edition to edition our basic framework has been retained, but it’s flexible enough to be revised and fleshed out. Changes in film technology (digital cinema, prosthetic makeup, performance capture, 3-D) have prompted us to trace their effects on style. New developments demanded new concepts and names (“network narratives,” “intensified continuity”). Our research for other writing projects gave us deeper awareness of Asian film, early cinema, ensemble staging, and other subjects we’ve incorporated into our general perspective. Tough subjects to talk about, like acting, have challenged us to come up with some new ways of thinking about them. We’ve found old films that we want people to see; we think that we should also be educating taste and getting students acquainted with things beyond recent releases and cult classics. And of course new films have been made that demand attention—not only because students are aware of them but because the art of cinema continues to grow before our eyes.

The eleventh edition has changes small and big. Of course we’ve rewritten stretches to make them clearer or sharper. We’ve added new examples from about fifty films, from Nightcrawler and Brave to Zorns Lemma, Searching for Sugarman, The Act of Killing, and Beasts of the Southern Wild. The biggest changes involve a recast section on 3D, with discussion of House of Wax and The Life of Pi; a new section, “Film Style in the Digital Age,” with concentration on Gravity; a new section on genre devoted to the sports film (with Offside as a key example); and, as the cover tips you off, an extended analysis of Moonrise Kingdom, a favorite on the blog as well (here and here).

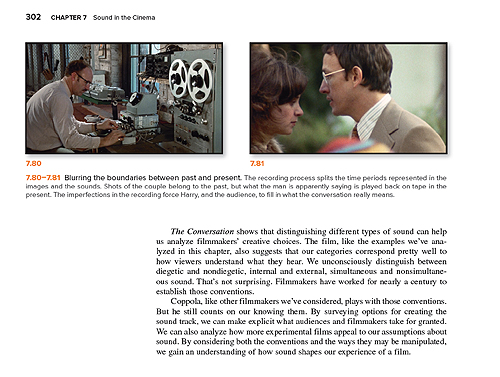

Jeff Smith (right, grinning) is responsible for many of these new attractions, and he has overhauled the entire sound chapter, with examples and analyses of Blow-Out, Norma Rae, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Nutty Professor (Jerry Lewis version), and The Conversation. In addition, Jeff has written a whole new chapter, number 13, on Film Adaptation. It is brilliant. It’s available as an add-on to the print edition for faculty who want to include it, and it comes along free on the electronic edition.

Jeff Smith (right, grinning) is responsible for many of these new attractions, and he has overhauled the entire sound chapter, with examples and analyses of Blow-Out, Norma Rae, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Nutty Professor (Jerry Lewis version), and The Conversation. In addition, Jeff has written a whole new chapter, number 13, on Film Adaptation. It is brilliant. It’s available as an add-on to the print edition for faculty who want to include it, and it comes along free on the electronic edition.

Under Kristin’s direction, with the kind cooperation of Criterion, we have added new video examples to the Connect online platform. Those include sequences from L’Avventura, Ivan the Terrible, I Vitelloni, and other major films, with voice-over commentary by one of us. In addition, our production guru Erik Gunneson has made a marvelous demo explaining sound mixing techniques.

In all, we’re very happy with the way the book has turned out. The pictures are vibrant, the design is crisp, and there are new marginal quotes and links to blog entries. As ever, the blog offers annual suggestions for integrating it with courses. We’ve also put up some video lectures on this site, listed on the left of this page, and of course people are free to use them in classes. A couple weeks ago we gathered some key blog entries around a central topic in Film Art, the nature of classical film narrative. Finally, as we’ve proceeded through many editions, we’ve had to cut several analyses of particular films. But those are still available as pdfs online; most recently,we posted our in-depth study of sound and narrative in The Prestige.

All these supplementary materials are attempts to illustrate and develop the ideas we’re proposing in Film Art–and to do so in a clear, concrete way. As we say in our introduction to the edition:

In surveying film art through such concepts as form, style, and genre, we aren’t trying to wrap movies in abstractions. We’re trying to show that there are principles that can shed light on a variety of films. We’d be happy if our ideas can help you understand the films that you enjoy. And we hope that you’ll seek out films that stimulate your mind, your feelings, and your intelligence in unpredictable ways. For us, this is what education is all about.

We remain grateful to the colleagues, instructors, students, and general readers who have supported what we’ve tried to do.

As part of McGraw-Hill Education’s multimedia publishing program, Film Art 11e is available in many formats, including a print edition and digital editions that meet the needs of entire film courses or independent readers.

*As always, instructors, students, and general readers can get a print copy of the new Film Art. It is available in bound or binder-ready form. Instructors who wish to order a custom print edition may include the bonus chapter on film adaptation.

*If you teach a course using Film Art, you can choose the digital option: Connect. Connect is a course-oranization tool that enables faculty to assign reading, submit writing, take assessments, and more. Connect gives students access to a subscription-based digital version of the book called SmartBook. SmartBook has the Criterion video tutorials embedded, plus the ability to assign all of the pre-built quizzes, practice activities, and other features. SmartBook includes the new chapter on film adaptation, along with additional material including our suggestions on writing a critical analysis of a film, and additional bibliographic and online resources.

Connect can integrate with your school’s learning management system, making it easy to assign and manage grades throughout the semester. Students will get access to SmartBook for 6 months; an instructor account does not expire, so you can reuse your Connect course semester-after-semester. Instructors may contact their local McGraw-Hill Higher Education representative for more information at http://shop.mheducation.com/store/paris/user/findltr.html. (Enter your state and school to find your rep’s name and email address.)

*If you want to read the book independently in digital form, you may choose standalone SmartBook. This version does not contain Connect’s course-administration supplements. The Criterion Collection video examples are embedded in the SmartBook for you to access any time throughout the subscription period. Students can opt for the SmartBook in place of a printed text, even if their instructor is not requiring Connect.

For more information: The buying options are explained here in general and the choices pertaining to Film Art are listed here.

We’re grateful to our editor Sarah Remington, as well as to Susan Messer, Sandy Wille, Dawn Groundwater, and Christina Grimm, for all their help on this edition!

Kristin’s 1977 chapter outline for the first edition of Film Art.