In the mood for WKW

Sunday | March 6, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

In the Mood for Love (2000).

DB here:

For quite a while, many of us have been looking forward to a book called Wong Kar-wai on Wong Kar-wai, a collection of interviews conducted by Tony Rayns. Alas, that is evidently never to be, for reasons that Tony hints at in his new BFI monograph on In the Mood for Love. Bits of those interviews make their way into the book anyhow, along with information and ideas reflecting Tony’s unique access to Hong Kong’s illustrious filmmaker. All lovers of WKW will want this energetic, accessible study.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

The thankless task of providing a detailed synopsis is carried off briskly, sustained by many explanations of culturally specific references. We learn of the daibaitong, the open-air restaurant where both Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan stop for a night’s noodles. We’re led to notice the inside joke about wuxia novels’ outlandish plots, as well as the changing of seasons as reflected in costumes. The synopsis is also sprinkled with critical-analytical points about parallels between the characters, relationships merely hinted at, and cross-references among the kindred films.

The talk around the Jet Tone office during the production of In the Mood for Love was of Chow Mo-wan setting out to seduce Mrs. Chan as a prelude to abandoning her: an act of wilful emotional cruelty intended as a revenge for being cuckolded himself. This inference is nowhere evident in the film as released, so Wong perhaps recycled the idea into Chow’s smiling rejection of a romance with “taxi-dancer” Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi) in 2046–although that rejection is itself a gentler replay of the playboy’s treatment of Carina Lau’s needy hooker Lulu, also known as Mimi, in Days of Being Wild.

There’s also quite a lot about the soundtrack, with close attention to the recurring melodies in the score and to the shifts between Cantonese and Shanghai in the dialogue.

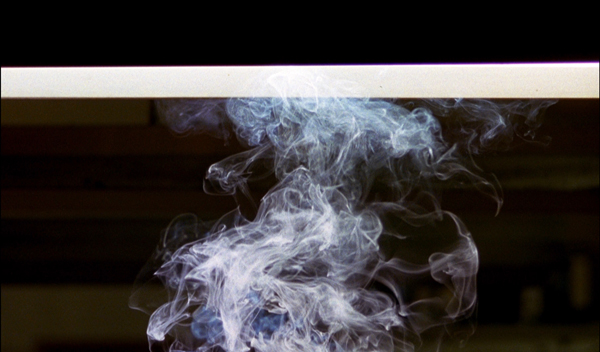

After the synopsis comes an analysis/interpretation. When the central couple reenacts their spouses’ affair, Tony suggests they’re testing the limits of their own inhibitions. He stresses the distinctiveness of Wong’s style, from its cinematic punctuation (the synopsis has emphasized the patterns of fades and straight cuts) to its handling of time–especially the strategically opaque narration, its “ostentatiously selective presentation of the action.” Of course the guilty spouses are never fully shown, but Tony also traces how time is skipped around via flashforwards and ellipses, sometimes barely noticeable ones. He points out how one cut relies on false continuity. Smoking alone in room 2046, Chow hears a knock on the door. Cut to a long shot of Mrs. Chan at the door–but she’s leaving.

We’ll never know what transpired during her visit. This exemplifies Wong’s “discontinuity in continuity”; flowing music, gentle tracking shots, and slight slow motion create a smooth surface that can conceal crucial information.

Tony has more to tell than the BFI format can squeeze in. I’d like more on the way quite disjunctive techniques fit into the film’s stylistic sheen. Wong deploys off-center framings, judicious use of depth in apparently real apartments, and variations in lighting among Hong Kong, Singapore, and Kuala Lampur. Tony’s hunch about continuity covering discontinuity might be extended to these aspects, and of course insider information on these matters would be welcome. I also wonder: Could there have been a hotel at the period boasting twenty stories? My Hong Kong friends say not. Tony argues that Wong’s films aren’t deeply political, but he was willing to violate plausibility to invoke the fateful year when HK becomes integrated into China.

Calm and ingratiating, the monograph is disarmingly personal as well. (How many books on a director start by noticing that the author has been dropped from a Christmas-card list?) It’s agreeably contrarian too. Tony teases academics, claiming at one point that the clock shots are “self-parodies” and “sucker bait” for critics who believe that Wong is the great cineaste of time. The book ends with a miscellany of observations about actors in bit parts, filmic offshoots of the project, and a little gossip. In all, reading In the Mood for Love gets you in the mood for In the Mood for Love.

Tony Rayns tells more in interviews on the Blu-ray disc of In the Mood for Love available from Criterion. That version of the film’s color seems far superior to other DVD versions I’ve seen, some of which have a dim, brownish cast. This is a hard film to replicate, though, as I found in taking 35mm frames: the tonal range is extraordinary, and your choice is often between exaggerating and lowering contrast.

Tony makes reference to the famous epilogue of Days of Being Wild that shows Tony Leung Chiu-wai, an apparently brand-new character cryptically introduced in this scene. The shot implies that there’ll be a sequel, and Wong has occasionally suggested the possibility. But there is a version of the film that includes a prologue showing the same character dressing to go out. Along with that scene is a sensuous passage in an underground gambling parlor. The sequence looks forward to imagery in In the Mood, including a sinuous shot of a woman ascending a staircase. If Wong chopped off the prologue to create the version of Days we have, he perversely left the dangling epilogue to tantalize us. For more about this “lost” version see my entry “Years of Being Obscure.”

I analyze Wong’s career, along with In the Mood for Love, in Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and I talk about The Grandmaster (which Tony considers a weak entry) here. I offer thoughts as well on Ashes of Time Redux. This project was the casus belli for Tony’s departure from Planet WKW. “The sometimes hair-raising tales of my experiences with Jet Tone will have to wait for another time.” What if we can’t wait?

In the Mood for Love.