Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948)

Tuesday | March 22, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

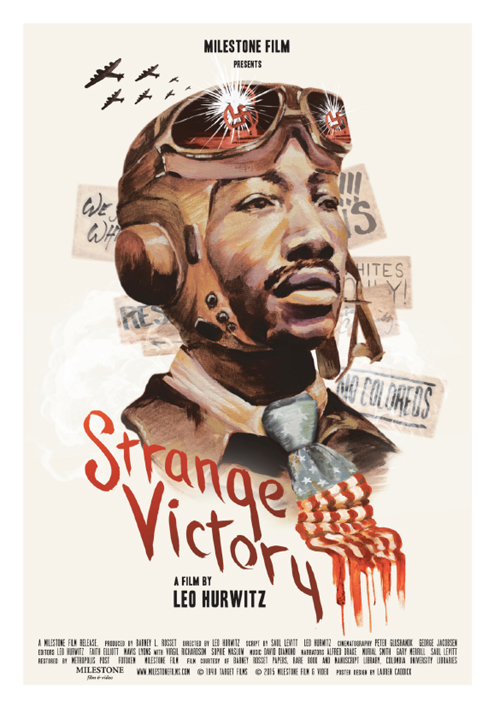

Leo Hurwitz is perhaps best known for Native Land (1942), the documentary codirected with Paul Strand and narrated by Paul Robeson. Strange Victory (1948) has been less easy to see. It was scarcely distributed and, though some reviews praised it, it was accused of Communistic sympathies. Now, restored and recirculated by the enterprising Milestone Films, Strange Victory has lost none of its compassion and righteous anger. Thanks to the energy of the Milestone team, led by A my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

In a period of postwar optimism, Hurwitz and his colleagues dared to point out that the prejudices exploited by the Nazis remained powerfully present in the United States. The winners, it seemed, hadn’t repudiated the bigotry of the losers. American racism persisted and even intensified. The Nazis lost, but a form of Nazism won.

Dec. 14, 2015, in Las Vegas. Individuals at a Trump rally yelled “Sieg Heil” and “Light the motherfucker on fire” toward a black protester who was being physically removed by security staffers.

News of the world

Like The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), on which Hurwitz was cameraman, and the Why We Fight series, Strange Victory is largely a compilation documentary. Guided by voice-over narration, it ranges across newsreels of Hitler’s rise, chilling combat shots, and footage from the liberated death camps.

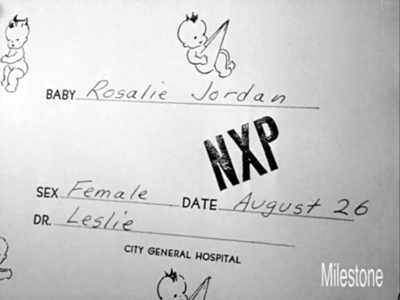

But Hurwitz and his team shot a lot of new material as well, with an eye to bringing out the postwar significance of their theme. Newborn babies eye the camera, and kids play on sidewalks and in backlots (some shots recall Helen Levitt’s evocative street photos). Meanwhile, anxious adults approach a newsstand. “If we won, why are we unhappy?” the narrator asks at the beginning. The question is answered at the end: “There was not enough victory to go around.”

Thanks to a hidden camera, that newsstand becomes a sort of gathering spot, a place where people might encounter uncomfortable truths. Intercut with people buying newspapers are images of battles, as if the hunger for news aroused by the war didn’t dissipate. But what is that news? Hurwitz introduces it quickly: the rise of nativist bigotry. In an eye-blink, racist decals are slapped on fences, synagogues are smashed, and vicious pamphlets swarm through the frame. Race-baiting politicians, radio hate-mongers, and fascist sympathizers–the 1940s equivalents of our celebrity demagogues–are pictured and named. This is just one of many passages that guaranteed that Strange Victory could never be circulated on mainstream theatre circuits.

Hurwitz mixes found footage, stills, posed images, and fully staged scenes, such as the episode in which a Tuskegee Airman tries to find a job with an airline. In this mixed strategy he follows not only the precedent of the March of Time series but also, and more self-consciously, the Soviet documentarist Dziga Vertov.

In a 1934 article, Hurwitz called The Man with a Movie Camera “the textbook of technical possibilities,” and he isn’t shy about mimicking the master. Early in the film, portraying the Allies’ victory, a shot shows a swastika-emblazoned building blown to bits in slow motion. Later, to convey the return of Hitlerism, the same shot is run backward, reinstating the swastika on the building’s roof. A graphically matched dissolve equates a Klan wizard with Southern senator John Elliott Rankin.

Later, via constructive editing à la Kuleshov, parental pride is made color-blind, as both a white mother and a black one return a father’s glance.

The film hasn’t aged a bit. The print is gorgeously subtle black and white, and the score by the underrated David Diamond is warm in a chamber-music way. The film’s vigorous voice-over and its ricocheting images (some returning as refrains, bearing new implications) look forward to the hallucinatory, expanding associations created by our most biting contemporary documentarist, Adam Curtis.

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

One of the individuals involved in the confrontation with Nwanguma was Joseph Pryor, a native of Corydon, Indiana, who graduated from high school last year. After the rally, Corydon posted a photo on his Facebook page that showed him shouting at Nwanguma. The post went viral and eventually attracted the attention of the Marine Corps, which Pryor had just joined.

The Marine Corps recruiting station in Louisville told military publication Stars and Stripes that Pryor had recently enlisted and was about to head off for boot camp. Captain Oliver David, a spokesman for the Marine Corps command, said Pryor had not yet undergone Marine Corps ethics training. . . . He added: “Hatred toward any group of individuals is not tolerated in the Marine Corps and he is being discharged from our delayed entry program effective [Wednesday].”

The tyranny of facts

As ever, the ordering of parts matters greatly. How best to convey the idea that after a struggle to cleanse Europe of violent prejudice, the same attitude is flourishing in America? You might think of couching your argument as a narrative. In chronological order, that would be: The rise of Hitler; the war defeating Hitler; the celebration of victory; the return of American bigotry in the postwar period. Clear and straightforward.

Hurwitz is more canny. Many films embracing rhetorical form, like the problem/solution structure of Pare Lorentz’s The River (1938), will embed brief narratives into their overarching argument. This is Hurwitz’s approach, but his stories aren’t chronologically sequenced. Instead, we start with the America of today before flashing back to the high price of defeating the Axis. “Everybody paid,” says the male narrator. “Everybody.” With a pause to register Roosevelt’s death, jubilation surges up as the Nazis fall. “For a day or two, the plain people owned the world.” But then we’re back to the newsstand and a montage of race-baiters and graffiti scrawlers.

Then, as we see a pregnant woman on a bench, we hear a woman’s voice. Her poetic musings reassure the newborn babies that they have a place here; she welcomes them to earthly love. Following the montage of haters with images of innocence casts a melancholy pall over these fresh-begun lives. They know nothing of the American brownshirts, but we know that they must learn our world.

This foreboding is confirmed by a chorus of name-calling over shots of newborns, the woman’s song of innocence is undercut by a song of bitter experience. A new male narrator (Gary Merrill) raps out the facts of “our daily barbarisms.” Get ready, he warns the babies: You will be tagged and vilified by how you look and where you live. “Separation of people is a living fact,” and they are future “casualties of war.” Throughout the rest of the film, the shots of children carry a terrible aura; they have no idea of what they’re facing.

Now, after a long delay, we flash back to Hitler’s rise. The Führer’s strategy, funded by the rich, is seen as a deliberate mobilization of just these tribal “facts” for the sole end of acquiring power. And where that process ends is the death camp. In a chilling visual refrain, the happy American toddlers are compared to troops of children marched along barbed wire.

The narrative spirals back to the beginning. Again we see Hitler defeated, again ecstatic celebrations–but not, as before, among civilians in cities. Instead, we see Russian and American soldiers fraternizing, and included in this mix is the black pilot, smiling serenely in his cockpit. His presence was foreshadowed by swooping aerial shots of the beginning. Now we’re back to the present, and he’s looking for work. No luck; maybe he can be a porter? A new montage generalizes his plight: American society refuses to assimilate African Americans. A savage cut takes us from a room full of white secretaries to a cotton field–the only work available for people who participated as fully in the war effort as anyone.

Now the early montage of Jim Crow images is recalled in a poetic string of associations on the word word, from Hitler’s control of The Word to signs barring blacks from entry, ending with inscriptions etched on forearms.

The final images of passersby, filmed unawares, replace the newsstand of the opening with shop windows as they peer inside. The sequence uncannily predicts the explosive consumer society that would follow in the war’s wake. Again, though, a shadow falls over the postwar world. Hurwitz daringly intercuts the intent window-shoppers with the plunder of the camps–hair, jewelry–and the numbers on inmate uniforms, as if these were commodities on display.

The war against inhumanity is far from over. Americans will need to be more than curious consumers if they are to face the struggle that lies ahead.

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

Strange Victory is, it seems to me, the essential documentary of our moment. A nearly seventy-year-old film can remind us that, as the narration puts it, “hopelessness is next door to hysteria.” The frustrations, despair, and hatreds that surfaced during Obama’s tenure have crystallized in an American fascist movement of unprecedented breadth. The film reminds us that scapegoating is eternal, sometimes summoned quietly (they’re not like us, she’s a traitor, he knows exactly what he’s doing), sometimes conjured up in full fury. At a moment when America is one IS attack away from a Trump or Cruz presidency, it’s good to be reminded how the well-funded Hitler exploited Us vs. Them. Temporizing pundits give every sufficiently funded lunatic the benefit of straight-faced interviews, or even tongue-baths. Right-wing politicians and agitators, keen on power and uncommitted to principle, are ready to fall in line behind a leader if he might win. Forget Godwin’s Law. Facing today’s assault on peace and justice, Strange Victory can rekindle our energies, without a moment to lose.

The crematorium is no longer in use. The devices of the Nazis are out of date. Nine million dead haunt this landscape. Who is on the lookout from this strange tower to warn us of the coming of new executioners? Are their faces really different from our own? Somewhere among us, there are lucky Kapos, reinstated officers, and unknown informers. There are those who refused to believe this, or believed it only from time to time. And there are those of us who sincerely look upon the ruins today, as if the old concentration camp monster were dead and buried beneath them. Those who pretend to take hope again as the image fades, as though there were a cure for the plague of these camps. Those of us who pretend to believe that all this happened only once, at a certain time and in a certain place, and those who refuse to see, who do not hear the cry to the end of time.

Milestone, who gave us the restored Portrait of Jason, has provided a very full presskit for Strange Victory here. My final quotation comes from Jean Cayrol’s text for Night and Fog (1955).

Strange Victory (1948).