Archive for April 2016

Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist

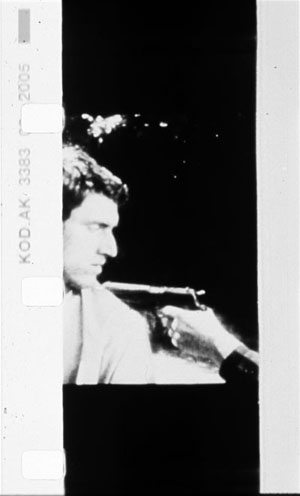

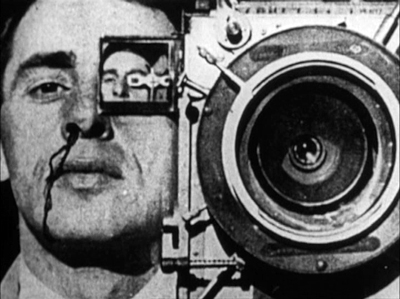

Anonymatograph (1972).

DB here:

Since the late 1960s, the Italian filmmaker Paolo Gioli has been employing procedures that are almost frighteningly stripped down. He has made films without cameras. He has devised his own cameras, often without lenses or shutters or motor drives. When he needs a shutter, his fingers, or perhaps some leaves from trees, will suffice. He has embedded images within images without benefit of optical printers, and he has brought photos to frenetic life without animation stands. When he needs a camera, a modest old Bolex or Bell & Howell will do fine. Impresario of clamps and masking tape, he creates extraordinary films with equipment that looks distinctly knocked-together.

The overused term DIY doesn’t capture the eccentric craftsmanship of a filmmaker who starts from the most basic features of cinematic material: film stock, perforations, light. Everything else, even the frame, can be treated as an add-on. These films are hand-made with a vengeance.

Sparse as the equipment and approach are, the results are overwhelming. Gioli’s films can be quietly lyrical or explosively aggressive. Most are fairly compact—fifteen minutes or less—but all are dauntingly dense. Each one’s fusillade of images would be enough for a feature. Skittering and jumpy, emitting a spray of single frames, the most fast-moving ones benefit from being black-and-white and silent: nothing distracts from the swarming images’ direct hit on your eye and brain.

Last weekend, the Harvard Film Archive hosted an event honoring Gioli, his long-time producer Paolo Vampa, and my Wisconsin colleague Patrick Rumble, a tireless advocate for Gioli’s cinema. Head archivist Haden Guest, another long-time supporter of Gioli’s work, timed the gathering with the release of Gioli’s collected works in a three-DVD set from Raro. That collection is a must for anyone interested in experimental cinema. Along with the films it includes Patrick’s seminal essay, “Free Films Made Freely,” and his superb documentary on Gioli’s life and working methods.

I was lucky enough to be present too, thanks to the accident of my having written a little on Gioli way back when. I think it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all—not least because seeing a rich sampling of the work on the Archive’s magnificent big screen made these films, at once rough-edged and precise, even more powerful than when they’re seen on a monitor.

Back to basics–real basics

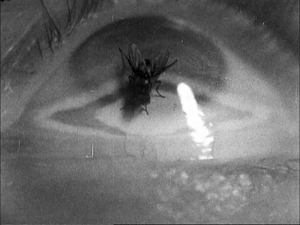

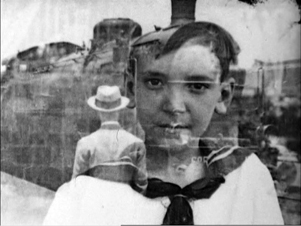

When the Eye Quakes (1991).

There’s no easy way to sum up the great variety of these films, but I owe you a sense of what they’re like. Start with the ones based on the physical stuff of the medium.

Gioli began as a painter and became both a photographer and filmmaker. He came to cinema as a result of his youthful stay in New York, where he encountered the New American Cinema. It’s not hard to see an overlap with filmmakers like George Landow (Owen Land), Ken Jacobs, and others whose films were based on displaying grain, scratches, perforations, and other physical properties of the medium. But instead of the Cagean repetition of Landow’s Film in Which There Appear Edge Lettering, Sprocket Holes, Dirt Particles, Etc. (1966), Gioli’s Commutations with Mutation (1969) bombards us with weaving, sliding, rolling strips of film (Super-8, 16, 35), all yoked violently together.

Already one sees a major motif of Gioli’s work, the frame-within-the-frame. The sprocket holes become miniature versions of the frame that can’t contain the agitation of the film stuff spilling across it.

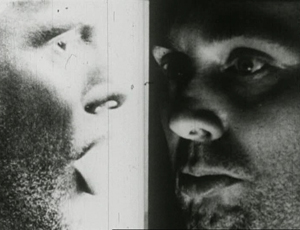

When the film gets more representational, as in According to My Glass Eye (1971), the split screen still suggests two or more films crammed into the same frame. Human faces and figures are wrenched into obsessive symmetries, mirrorings, and embeddings.

The pounding oscillation of this film, made of hundreds of different frames, is unremitting. It’s a sort of anti-Muybridge experiment: instead of decomposing action into bits, the fragments are whipped into a frenzy. The motion is insanely fast, with bodies surging in convulsions as eyes roll and pop terrifyingly. Most Gioli films are silent, but here the aggression is accentuated by driving drum rhythms.

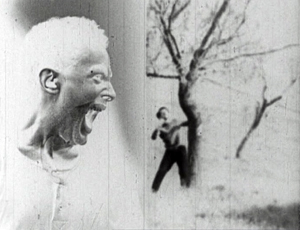

The same primal thrust comes from When the Eye Quakes (1991), one of Gioli’s found-footage efforts. Starting from the woman’s slit eye at the beginning of Buñuel’s Andalusian Dog (1929), we get a sort of pictorial cadenza. Bunuel’s original metaphorically linked eye to moon, cloud to a razor slicing it. In Gioli’s remake, a fly crawls on the eye, the eye is peeled open to reveal a flurry of abstract patterns inside, the gash is stitched shut, and the whole array triggers REMs in another pair of eyes.

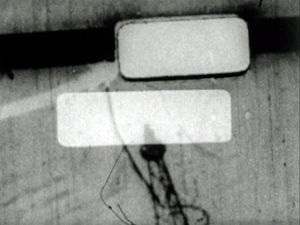

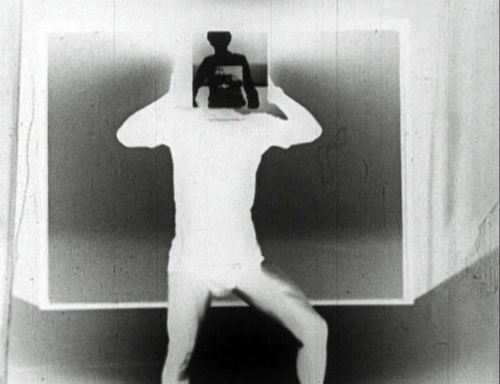

The agreeably assaultive side of Gioli’s work finds an emblem in his painting Superficie vasta della sorgente (1970). Here a rectangle serves as the screen, and two trapezoidal paintings mimic the projector beam.

The whole ensemble suggests not only a projector sending images to a support but a torrent of images pumped out to punch the viewer.

A more leisurely found-footage film is The Perforated Cameraman (1979), which stops and restarts shots from a silent comedy. Those images are haunted by yet another variant of the frame: wide-angle rectangles drifting in and out.

One such shape turns out to be a ghostly version of the center perforation of the 9.5mm format. That’s the format of the source movie itself, which is, in another reflexive twist, about the making of a movie.

Optics, mechanics

Paolo Gioli demonstrates one of his pinhole cameras as Paolo Vampa looks on.

Gioli has said that he wants to free himself from cinema’s reliance on “optics and mechanics.” Accordingly, he has reverse-engineered, or rather de-engineered, the apparatus of image-making. Take his various experiments with pinhole imagery. He has pushed the idea of the pinhole photograph (of which he has made many) to another level with pinhole movies.

He started with buttons, using their holes as light-gathering apertures. But since a shirt’s buttons are arranged top to bottom, why not do the same with pinholes? Accordingly, he devised a tube punctured at regular intervals, like a flute. The tube has a chamber for a film strip, with one pinhole per frame. The “shutter” is a hinged strip of metal that opens and shuts to expose the film.

To make the shot the “camera” is held upright. What’s hard to get your mind around is that the frames aren’t exposed sequentially, but all at once. They present varying angles on the subject at one instant.

When developed and run through a projector, however, they gain a temporal dimension. The footage presents an object that seems to slide vertically into view, framed by serrated edges and illuminated by irregular flares of light. Because the first images we see in a shot are those at the bottom of the tube, we may get the effect of a rising camera movement, when in fact there was none. A bowl of fruit in the foreground sinks out of sight as we seem to withdraw from a window.

Each tubular camera yields “takes” of more or less constant length; one tube is two meters long, another is only about 50 frames. Assembled (usually in camera rather than in postproduction), the shots arrive in a regular rhythm. Sometimes the footage displays another in-camera montage: Gioli has cut the hinged strip into two parts, so that he’s able to expose the top part of the film in taking one “shot,” then, separately, another strip of frames at the bottom. And sometimes the upper edge of the motif is cropped and it creeps in from the bottom.

The rigid verticality of Film Stenopeico (aka The Man without a Movie Camera, 1973/1981/1989) and Natura Obscura (2013) seems to me another version of the way in which Commutations with Mutation created one long image on the film strip and then chopped it into bits in projection. What has no framelines acquires them during the screening.

In an essay posted on this site, I noted that these efforts toward a “vertical” cinema recalled Eisenstein’s call to repudiate the horizontality of the classic 4:3 frame. It’s also worth remarking that once you know how the pinhole films are made, you’re obliged to think of each film as having two modes of existence: the physical object threaded through the perforated cylinder, and the film as we see it, an upward scan of an object in our surroundings.

Seeing red

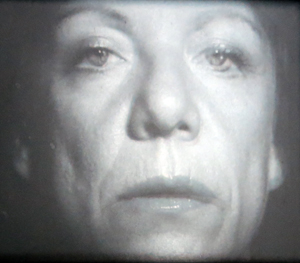

Patrick Rumble and Paolo Gioli explain the experiment Land’s Red (2014).

This “double film,” the duality of the physical and the perceptual in our experience of the movies, is there at the start of his career. On the screen, Traces of Traces (1969) vibrates with abstract patterns of contours, edges, and whorls; it takes on a different sense when you learn that Gioli made it by pressing fingers, sandpaper, rubber stamps, and body surfaces against the film stock. As ever with avant-garde cinema, the question What am I seeing? often comes down to How were these images made?

Gioli’s “new optics” makes him interested in perceptual phenomena like visual saccades (exaggerated to a terrifying degree by his frenetic fast motion) and color vision. Fascinated by the oddities of our visual system, he has “operationalized” Edwin Land’s early experiments in color perception. In an important 1959 article, Land considered the sources of color constancy—the fact that an orange looks about as orange in bright sunlight as it does in deep shade. Yet the lighting conditions are drastically different and should yield a different color sensation. Somehow our visual system “knows” to adjust for fluctuating illumination and yields a stable color world.

Land’s experiment filmed black-and-white still photographs through color filters, then displayed them as slides and tinted the projection beams. He discovered that under certain conditions, we can recover a wide range of colors from a combination of pure white light and a red filter. It’s as if our visual system, which is sensitive to three overlapping wavelengths of light, was endowed by evolution with a bit of redundancy. Moreover, color constancy suggests that perception of color is independent of degrees of illumination.

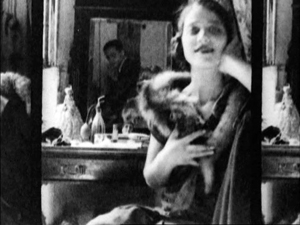

Gioli replicated Land’s experiment with motion pictures by creating black-and-white film loops (Land’s Red, 2014). During his Harvard Film Archive stay, he demonstrated the result, including a close-up shot of a woman with blue eyes and bluish-silver eye shadow. The left image is the double-projection without a filter, the right is the image with a red filter. We’d expect that putting the filter on tints the entire image red. Instead, the filter generates a range of color, from the vibrant lips to the pale blue of the eyes and eye shadow.

Land’s theory involves psychophysical matters I can’t claim to understand. I gather that his account of three wavelengths in our cones’ pigments is now seen as a partial explanation of color vision. His “retinex” theory—the idea that the retina isn’t the only source of color, that there must be coding of the wavelengths in the cerebral cortex too—pointed other researchers toward a computational account of perception. The eye is a part of the mind.

Gioli’s startling demonstration reminds us that experimental science and “experimental” cinema aren’t always so far apart. A lot of avant-garde films, such as those of Ken Jacobs (discussed a bit herabouts) constitute rich, poetic probes into the quirks of our vision.

A past remade

Gioli has quickened photographs through pixillation, creating movement out of stills with an almost childish simplicity. He just snaps frames from illustrated books. Filmarilyn (1992) uses images from a Bert Stern collection to evoke Marilyn Monroe’s flirtation with death. Perhaps Gioli’s most accessible film, Children (2008) is a succinct, somewhat mordant reflection that carries us from Avedon shots of John and Jackie Kennedy, romping with Caroline and John, Jr., to images from Jacob Riis’ investigation of poverty in New York, and then to the imagery of the My Lai massacre.

Gioli has also done a kind of archeology of early film, as in his homage to chronophotography Little Decomposed Film (1986). My own favorite of his works is the lyrical and melancholy Anonymatograph (1972). In some ways it’s parallel to the work of “Structural” filmmakers like Malcolm Le Grice (e.g., Little Dog for Roger, 1966). The principal source is 35mm material of 1910-1930s from an unknown cameraman. The anonymous photographer recorded families and street scenes, both posed figures and spontaneous laughs and yawns. The footage was shot on an unusual Zeiss camera that could take both still images and motion pictures (a machine ideally made for Gioli).

Gioli’s reworking is typically high-strung, with nearly single-frame imagery at various points. Yet it doesn’t seem jittery. Despite the pace, the film proceeds majestically. It’s at once celebratory, showing gorgeous people, grave or gay, turning to or from the camera, and mournful, as the progression of shots takes us toward war and fascism. There are glimpses of “folk porn,” and hallucinatory superimpositions recalling juxtapositions out of Magritte or Paul Delvaux.

Gioli endows these long-dead divas and sturdy gentlemen with graceful, almost tragic unawareness of their place in history. Anonymatograph goes beyond his pure experiments with light, shape, and the skin of the film. It’s a testimony to the subtle power of old pictures and to an artist’s ability to reimagine, without abandoning any of his nervous intensity, the world they captured. No wonder Patrick Rumble calls Gioli “the last of the first filmmakers.”

I haven’t dealt with the full range of Gioli’s work. I’ve neglected the paintings and photographs, and I’ve had to neglect his powerful “photofinish” films (e.g., Slit-scan Figures, 2009). I just hope I’ve intrigued you enough to induce you to explore this unique and unpredictable filmmaker.

Thanks to Haden Guest for inviting me to participate in the HFA event, to Jeremy Rossen for help during my visit, to Patrick Rumble for many discussions of the films, to John Powers of Madison for information about optical printing, and of course to Paolo Vampa and Paolo Gioli for sharing ideas and information.

The Gioli collection is distributed in the US by the far-sighted company Kino Lorber. There’s also a book of essays, Paolo Gioli: The Man without a Movie Camera, ed. Alessandro Bordina and Antonio Somaini (Mimesis, 2014). The official Paolo Gioli website is here.

The Edwin Land articles are “Experiments in Color Vision,” Scientific American (May 1959), 84-99. and “The Retinex Theory of Color Vision,” Scientific American (December 1977), 108-128. A good biography of this remarkable man is Victor K. McElheny, Insisting on the Impossible: The Life of Edwin Land (New York: Basic, 1999).

L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema

Kristin here:

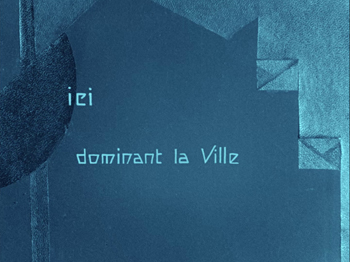

Flicker Alley continues its relationship with Lobster Films of Paris, bringing out beautifully restored versions of French silent films, and in particular the work of the French Impressionist filmmakers. The recent release of Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1924) is stunning visually. L’Herbier produced the film himself with his new Cinégraphic company, and hence he preserved the negative. With the original art-deco intertitles (below) and the colors as chosen by L’Herbier, this is as close as one can get to a version that is identical to the original release prints.

We’ve described earlier Flicker Alley releases of classic French silents in restorations: the extraordinary output of the Russian emigré firm Albatros, the long-lost serial La Maison de mystère, and Abel Gance’s La roue. L’Herbier’s Feu Mathias Pascal (1926), made directly after L’Inhumaine, was in the Albatros set but also released separately.

Although I’ll be mentioning most of the major plot points of L’Inhumaine, I’m not posting a spoiler alert. The action does involve some nominally suspenseful situations, but L’Herbier signals what’s going to happen so far in advance that I suspect few people watching the film would be surprised by the “twists” in the story.

The film’s plot is, to put it bluntly, weak. The “inhuman one” of the title is Claire Lescot, an opera singer who delights in frustrating the powerful suitors and would-be seducers who gather at banquets that she stages in the spectacularly designed rooms of her lavish home. In the opening dinner scene, she is particularly cool to Einar Norsen, a brilliant but naive young inventor who is in love with her. When he seemingly threatens suicide, she laughingly remarks that his life cannot mean much if he can throw it away.

Shortly after, word comes that Norsen’s car has plunged over a cliff into a river. The news makes Lescot realize that she loves him. Grieving, she nevertheless performs at a scheduled concert, after which she is visited by a mysterious man who requests that she act as a witness in identifying Norsen’s newly discovered and mutilated body.

Shortly after, word comes that Norsen’s car has plunged over a cliff into a river. The news makes Lescot realize that she loves him. Grieving, she nevertheless performs at a scheduled concert, after which she is visited by a mysterious man who requests that she act as a witness in identifying Norsen’s newly discovered and mutilated body.

The mysterious man, as is obvious from the start, is Norsen in disguise, preparing an ordeal that will lead Lescot to renounce her cruelty and embrace humanity. (The plot of a man who takes the opportunity afforded by a false report of his death to adopt a new identity apparently fascinated L’Herbier. It would become the core of Feu Mathias Pascal, an adaptation of Luigi Pirandello’s 1904 novel.)

Once Norsen reveals himself to Lescot, he shows her his remarkable laboratory, including a machine that may be able to restore the dead to life.

Lescot’s interest in Norsen has enraged one of her suitors, Djohar de Nopur, and he kills her using a poisonous snake in a bouquet. Norsent rushes her to his laboratory and uses his new invention to revive her.

We learn very little about these characters. They are basically stock figures enacting a familiar melodrama. Georgette Leblance, who plays Lescot, was an opera singer who contributed half of the financing in exchange for playing the role. She employs the florid style associated with the great divas of the 1910s, emoting intensely and striking dramatic poses.

If one embarks upon watching L’Inhumaine as a compelling story, one is likely to be disappointed. Its fascination lies rather in the fact that this simple narrative is considerably embellished with flashy design and the novel depiction of scientific experiment.

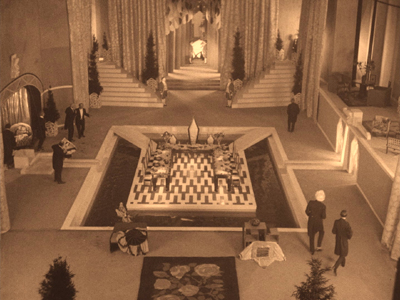

A leisurely stroll through some remarkable sets

“Flashy design” here means a great deal. L’Herbier had many prominent friends and contacts within the world of arts and crafts in 1920s Paris. The assemblage of collaborators who worked on the look of L’Inhumaine is quite overwhelming. The heroine’s clothes were by one of the leading fashion designers of the day, Paul Poiret, whose interior design department contributed some of the furniture in her apartment (below). The sculptures in her home are by Joseph Csaky, a Hungarian-born Cubist.

There were four main set designers, with contributions by others. Modernist architect Robert Mallet Stevens created the exteriors of Lescot’s house (left) and Norsen’s (right).

By the way, one can still almost walk into a 1920s film today by visiting the Rue Mallet Stevens in Paris, here seen at the time of its inauguration in 1927.

Other designers included Alberto Cavalcanti, who designed the interiors of Lescot’s mansion, notably the huge dining and entertainment hall at the top of this section and a Caligaresque conservatory.

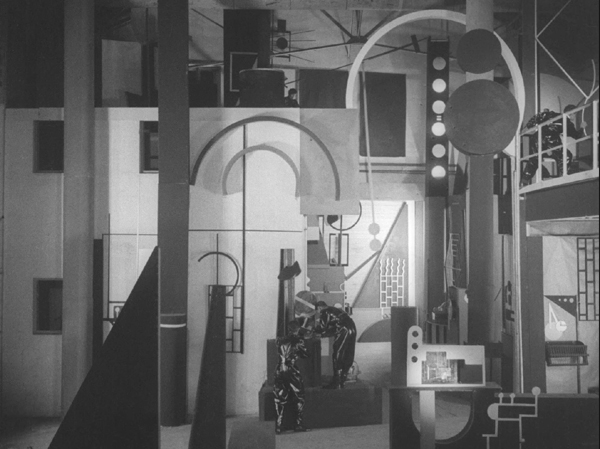

Perhaps most memorably, painter Fernand Léger planned and built the interior of Norsen’s lab (see bottom). More on this below.

The bare bones of the plot are so simple that L’Herbier can proceed at a remarkably leisurely pace through individual decors. In a period when most films consisted of long strings of short scenes, Claire’s opening banquet for her gentlemen guests lasts a remarkable 45 minutes. This includes cutaways to Einar driving rapidly to her house, dithering about whether he should appear late at the party, and finally, after her callous treatment of him, driving away to his apparent suicide. The second sequence, with Claire deciding to perform her song recital despite her grief over Einar’s death, lasts 25 minutes. The primary action here is simply a near-riot in the theatre between her supporters and those indignant about her part in the causing the young scientist’s death.

The lengthy final section of the film visits the laboratory three times, allowing us to get a good look at one of the great sets of the era.

Cinematic touches

L’Herbier did not entirely depend on his designers to carry the visual interest of the film. He was precocious in his use of wide-angle lenses, a technique that would become more prominent in his 1928 masterpiece, L’Argent. Here the lenses used give a less obvious effect, as in the shots of the jazz band that entertains during the opening banquet (above).

He also achieves some impressive compositions using considerable depth of field, most notably a close-up of the hero’s steering wheel as he tears along a road overlooking a deep valley with a city in the distance. It is here where his supposedly suicide takes place. Another striking shot has the jealous villain in the dark foreground, watching as the disguised Norsen enters Lescot’s dressing room.

Très moderne

Although the combined work of such a group of designers is the film’s primary attraction, L’Inhumaine is also notable as an early example of the science-fiction genre. Norsen’s technical genius is represented as going beyond the technology of the age. We see two instances of what he has invented.

The first marvel of Norsen’s laboratory that he demonstrates to Lescot is a television set (so named in the intertitle). Is this the first reference to television in the cinema? Possibly, though the script in quite an illogical way reverses the technology of how actual television would eventually function. Lescot performs a song into a microphone. Instead of a camera beaming her image out to viewers around the world, a screen in Norsen’s lab shows her images of various listeners reacting in delight to her performance–as if somehow cameras could be placed in every spot where someone, whether Arabs, a young black woman in an African field, or a family group in a tropical setting (below) is listening to her over a radio speaker.

The telephone system in Metropolis (1927) that includes screens upon which the speakers view each other reflects more reasonably what actual inventions were later to follow. One can’t help wonder, however, whether that device was inspired by L’Herbier’s film.

More spectacularly, the giant machines that Norsen uses to restore Lescot to life provide the climax of the film. When Norsen tours Lescot around his lab in an earlier scene, he shows her a huge apparatus, including three large, round components that swing through space like a moving Gabo sculpture (see top). He remarks that he believes the machine could restore a dead person to life, but he has not yet had the opportunity to test it.

Rather than trying to suggest how the machine works, the film keeps the set where Lescot lies dead simple and abstract. In perhaps the most famous image from the film, a ziggurat-shaped platform and some simple diagonal lighting tubes shape the composition, with Norsen nervously peering up to gauge the effectiveness of his invention (see top of this section).

The scene of Lescot’s revival consists of rapid, accelerated editing that had become a major trait of the French Impressionist movement by this time in the wake of La roue and Jean Epstein’s Cœur fidèle. There is no way to convey this remarkable sequence with frames from individual shots; the effect is achieved more by the rhythm of the cutting than by the composition of the individual shots.

The Flicker Alley Blu-ray comes with two alternative musical accompaniments, one by the Alloy Orchestra and an adaptation of the original Darius Milhaud score by Aidje Tafial. We listened to the latter, which worked very well with the film. There is also a helpful booklet of notes.