Archive for May 2016

The people have spoken

Terence Davies: Sunset songs

Sunset Song (2015).

DB here:

A career retrospective brought director Terence Davies to Astoria’s always enterprising Museum of the Moving Image. On Sunday MoMI ran a handsome 35mm copy of The Long Day Closes (1992), introduced by Sony Pictures Classics Co-President Michael Barker (who originally distributed the movie). The film was followed by Davies’ informative discussion with Michael Koresky, author of a fine critical study of Davies. On Tuesday, there was an avant-premiere of Sunset Song (2015) with Agyness Deyn, the principal player, joining Davies and Koresky. The first screening featured one of the greatest films of the 1990s, while the second showcased the literary adaptation that Davies had sought to make for several years.

The two evenings left me with renewed respect for the power of this audiovisual art we call cinema. They also set me thinking about Davies’ unique contributions to that art, particularly in his first two features.

MGM in Liverpool

The Long Day Closes.

If you needed proof of the unpredictable, zigzag influence of Hollywood cinema, look no farther than the films of Terence Davies. When he saw his first film, Singin’ in the Rain (1952), he knew utter rapture, and his early years were illuminated by visits to the local movie house. But unlike other cinephile directors, he didn’t turn retro. His first two masterpieces, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992), decant the splendors of American musicals into vessels more severe and melancholy. The brooding lyricism of these films, presented in a stringently geometrical pictorial style, makes them almost unrecognizable cousins of the 1950s films that nourished him.

Davies understood, as so many postwar critics of mass culture didn’t, that Hollywood, for all its formulas and conventions, captured genuine feeling; indeed, those very formulas and conventions released that feeling. In Davies’ hands, however, the feelings gain a rougher texture. In tales of patriarchal power and everyday betrayals, echoes of the yearning of Judy Garland and the vibrato of Doris Day seem distant and distorted. Davies finds the evanescence hidden in Yankee exuberance, and he takes it very personally.

That’s partly because popular song is filtered through a sensibility deeply committed to classical musical expression. Nobody but Davies would accompany an image of urban squalor with the arching final melody of Vaughan Williams’ Pastoral symphony, or the soft run of George Butterworth’s “Shropshire Lad” tune over the tan rug in The Long Day Closes. The soaring Barber violin concerto accompanies, for an astonishing eleven minutes, the opening images of The Deep Blue Sea (2011); it’s practically a cinematic tone poem. One of those directors who’s unthinkable outside the sound cinema, Davies dissolves any barrier between popular song and art music. The American Song Book, he says, is the country’s greatest gift to the world, and Stephen Sondheim is our Schubert.

Music is tied, in intricate ways, to family. These films are openly autobiographical. The first part of Distant Voices is a terrifying portrait of domestic life with a madman; the second part treats the radiant moments without him. The father is absent in The Long Day Closes, and so life in the household, with Mum and brothers and sister and visiting chums, is blissful. (Surely Davies is the great filmmaker of sibling devotion.) Now the threat lies beyond the threshold; school bullies, sadistic teachers, and a Church that seems indifferent to the suffering of a boy vaguely sensing his homosexuality.

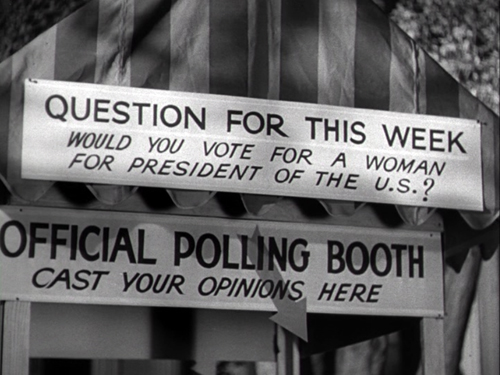

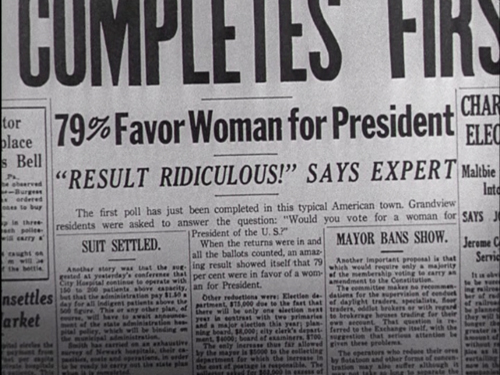

Yet by a kind of benevolent contagion, the joy of American cinema transfigures the grubby side of daily life–through communal singsongs in parlor or pub, through impromptu performances at parties, through hit-parade tunes hummed during daily routines. There are line-readings too; in The Long Day Closes the Boccherini minuet from the ball in The Magnificent Ambersons is matched by quick borrowings from Welles’ voice-over narrator. In one of the great sequences of modern cinema, a survey of the boy Bud’s world is shot from straight-down framings that roll by like scenes in a picture scroll. Birds’-eye views of street, cinema, church, and school are wrapped in the throbbing voice of Debbie Reynolds singing “Tammy.”

Cinema wins on the soundtrack. Take away the music and the snippet from Kind Hearts and Coronets and you have a grim topography. With movies, life’s miseries become bearable.

Chamber pieces

Distant Voices, Still Lives.

Distant Voices and The Long Day Closes balance social realism with a first-person quality shot through with feeling. Davies remembers everything about his childhood, and he can present unsentimentally the gray-brown wallpaper and the bulky furnishings. (He remarked that period films always forget that people didn’t have the most up-to-date things; nobody in 1950 Liverpool owned 1950 furniture.) Even realistic detail is saturated with memory and expression. Similarly, Davies’ reliance on planimetric shooting, dominant in Distant Voices and still strong in The Long Day Closes, creates at once rigid formality and a curious intimacy, as if we were looking at family portraits.

When capturing moments of serenity, the perpendicular shots evoke utter honesty; characters face us frankly, hiding nothing. But confronted with a schoolyard beating or a psychopath thrashing his wife, this curiously impassive camera–no wild handheld bursts or jagged cutting–only accentuates the pain. The camera’s unearthly calm takes on a kind of ruthlessness, as if nothing awful that happens in this world can make it flinch, just as nothing rapturous can make it go giddy. Davies seems fairly Wordsworthian: his poetry is “a spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling,” but the overflow is “recollected in tranquility.” The scene’s situation and the music, we might say, supply the feeling, while the framing supplies the tranquility and suggests the distance of memory.

These tableaus remind us that Davies is one of the few masters of cinematic chamber art. The exteriors, very few in these two features, are treated in the same rectilinear framings as the rooms are, as if one could never escape the carpentered contours of a house. More often, we’re indoors, and the human figures in are caught, nearly frozen, in a parlor or kitchen or hallway or schoolroom. No wonder his favorite painter is Vermeer.

Like Dreyer, Davies finds drama in the nearly closed room, the space slashed by light and opening onto somewhere else: in Davies’ case the doorway and the stoop and the street. These are the little theatres of human relaxation, of sharing, good times, and of course song. All the more jolting, then, when the father in Distant Voices turns up at the door, released from the hospital, or when Bud in The Long Day Closes sees his pal Albie go off to the pictures without him. As Michael Koresky notes in his book, the face at the windowpane looking out at the world is a recurring image for Davies: the edge between two arenas of experience, both harboring pain and exaltation.

Davies is famous for laying out each film with a draftsman’s precision: shot by shot, line by line, musical extract by musical extract. These films are absolutely through-composed. Their strict rhymes channel the feelings of the characters–or rather, the feeling of a scene as a whole–into determinate shapes that we can grasp. The sound is as important as the images; Hollywood musicals taught him the tight coordination of image and phrasing that pattern his song sequences and pictorial cadenzas.

Davies is famous for laying out each film with a draftsman’s precision: shot by shot, line by line, musical extract by musical extract. These films are absolutely through-composed. Their strict rhymes channel the feelings of the characters–or rather, the feeling of a scene as a whole–into determinate shapes that we can grasp. The sound is as important as the images; Hollywood musicals taught him the tight coordination of image and phrasing that pattern his song sequences and pictorial cadenzas.

No surprise, then, that Davies loves music and poetry, to which he constantly compares cinema. And no wonder he admires T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, that poem that takes its title from chamber music. In both music and verse, powerful feelings flow through rigorous forms. The chock-a-block construction of Distant Voices sets up poetic parallels and contrasts between the two parts. More boldly, The Long Day Closes offers a narrative that’s barely there: a suite of situations, a flow of anecdotes that gathers symphonic force. It recalls Pather Panchali and other films about a child coming to understand that whatever happens, painful or exhilarating, is transitory when seen against the backdrop of eternity.

Davies is after, he said in conversation, “the intensity of the moment,” and what happens before or after may seem of little account. Sound, light, color, movement: all become focused on the poignancy of the felt instant. Yet in another echo of Romanticism, that instant isn’t trivial when it’s seen in a cosmic context. Left alone by his brothers and sister, Bud thrusts his flashlight to the sky, creating a movie-projector’s beam as a demonstration that light goes on forever.

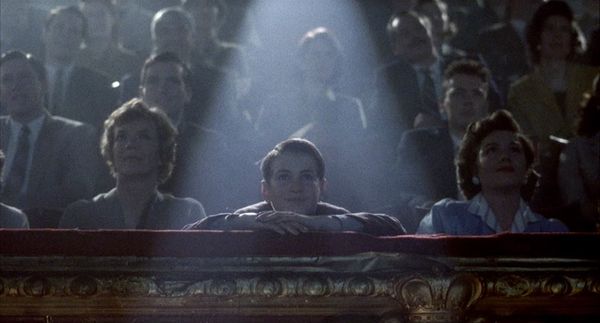

In an echo of this moment, Bud’s long days close with a merger of the momentary and the infinite. Two boys sit (in the balcony?) poised against the sky. Their movie becomes a majestic sunset, wrapped in the plangent song that gives the film its title. The light from the stars dates from Jesus’ day, Bud tells Albie, as the sacred chambers of his world open onto the universe.

Daughter of the earth

Terence Davies and Agyness Deyn.

A sadistic, baleful father; a mother bearing the brunt of his demands; a brother and sister as tender with one another as sweethearts; gentle friends who sustain the household with music–with Sunset Song we seem to be back in the world of Davies’ early films. But instead of the grubby city streets we’re in a glorious green-gold landscape of rolling fields, and instead of postwar London we’re in Scotland on the eve of World War I.

Sunset Song, drawn from the 1932 novel by Lewis Grassic Gibbon, exemplifies Davies’ later interest in adapting literary works (The Neon Bible, 1995; The House of Mirth, 2000; The Deep Blue Sea). In all of these, Davies tries to respect the spirit of the original while finding affinities with his own sensibility.

Sunset Song centers on Chris Guthrie, the dutiful daughter of a farm household. For the early stretches of the film she’s a cautious observer, but her voice-over, presented in the third person and past tense, prepares for her to take over the action. At first she’s inclined to run away with her brother, but duty keeps her home. When she comes into ownership of the farm, she realizes that she is rooted in the place. The earth, more eternally solid than sea or sky, gives her strength. If she cannot forgive what her father has done, she can learn to understand and forgive another man’s betrayal.

At first glance, we might seem to be snugly settled in British Cinema of Quality. But Davies has always made “costume pictures,” and his take isn’t in tune with Masterpiece-Theatre fashion shows. The clothes, as Davies always demands, look lived in, worked in, slept in. Agyness Deyn explained that for wardrobe they gladly took the worn leftovers of tonier productions.

Despite the eye-filling landscapes shot in 65mm, Davies hasn’t played false to his intimate aesthetic; this remains a chamber drama, with few primary characters. Like Bud in The Long Day Closes, Chris is our focal consciousness; apart from a substantial flashback to war-torn France, we’re confined chiefly to what happens around her. A few years of history unfold in a rhythm tuned to her growing awareness of her options and decisions, good and bad.

The style is far more mainstream than in the first two features. We get continuity editing (often in its constructive vein), smooth reframings as actors move around sets, and not many images recalling the tableau-vivant look of the earlier work. Chris is introduced in one of those twirling camera movements that are de rigueur nowadays, though Davies refreshes the convention by the visual metaphor of her rising up from the wheat, as if from sprung from the soil, and tipping her face to the sun, like a flower.

But Davies insisted on both evenings that for him, form springs from content. I take that to mean that the brick-by-brick shot assemblage of the first films suits the episodic, memory-driven nature of those tales. Here we have a novelistic saga (the original book is part of a trilogy), and so we must stay engaged with a chronologically unfolding plot. Davies has opted for less stylization, the better to rivet us to the powerful story of his protagonist’s blossoming to maturity.

Again, music yields a model. He urges young filmmakers to study symphonic cycles, like those of Bruckner and Sibelius, in order to appreciate scale and balance and variety in a large-scale structure. The relaxed flow of Sunset Song–and what power the title must have had for him–is like that of a full-scale orchestral essay. If Distant Voices, with its shifting, decentered viewpoint, is a chamber piece and The Long Day Closes is something like a song cycle for voice and quartet, this latest work is perhaps a concerto, with Chris’s sturdy presence an instrument of commanding range set against the massive landscape and a choir of family, friends, and neighbors.

Normally we must wait years between Davies’ films, but A Quiet Passion, his biography of Emily Dickinson, is beginning its career in worldwide distribution now. One feature in 2015, another in 2016. “I’m in danger of becoming prolific.”

Back in 2001, Kristin and I met Terence and his assistant John Taylor (loyal Packers fan) at Belgium’s summer film college. They were good company then, and still are. The MoMI screenings provided a wonderful occasion to see them and the films once more. If you’re in the vicinity, start queueing now for the follow-up items in the series. And Sunset Song opens this Friday at Film Forum, with Terence present. From there it will make its way across the US. You couldn’t spend your time more fruitfully. These movies will last a very long time.

Thanks to David Schwartz and his colleagues at MoMI. The Long Day Closes is available on DVD and Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection; thanks to Kim Hendrickson for her assistance. And thanks to George Nicholis of Magnolia Pictures, which is releasing Sunset Song.

For more on the stylistic tradition that early Davies films work within, you can consult Chapter Six of On the History of Film Style and these entries.

The Long Day Closes (1992).

Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts

DB here:

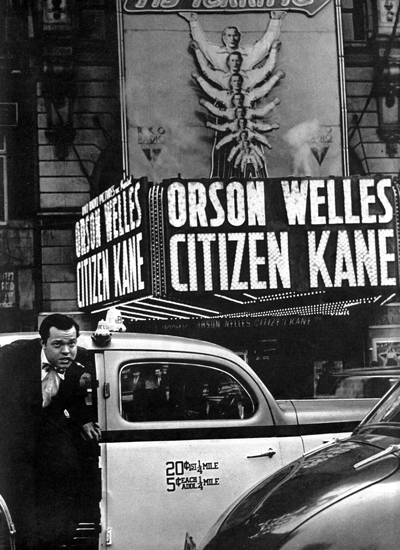

Kristin and I are one-third through our New York stay, and blogging has suffered. There have been talks to give, old friends to visit, new friends to meet, and movies and exhibitions to see. And there’ll be more activities of these sorts to come. But I can’t let 6 May pass without some acknowledgment of Orson Welles.

That’s partly because I just finished a draft of the Welles section of my 40s Hollywood manuscript. (Yeah, that beast was another distraction from blogging. All 158,000 rough-hewn words of it are now dispatched to some unwary readers.) So Welles was on my mind already when the anniversary of the “official” Citizen Kane release came up on 1 May.

Actually, by the time Kane had that roadshow release, it had been widely seen by the Hollywood community. In the face of the Hearst press’s attacks, RKO head George Schaefer held invitational screenings in early 1941 to build up support for the film. Variety estimated that by late March 1,200 producers, directors, writers, actors, and agents had seen the picture. The number was so big that RKO dispensed with a splashy Hollywood opening. (The article title is pure Varietyese: “So Many Cuffo Gloms at ‘Kane’ It Kayoes Idea of a $5.50 Preem,” Variety, 2 April 1941, 2, 20.) As a result, I think, Kane‘s influence began to be registered some months before its New York premiere, as the look of The Maltese Falcon (shot June and July of 1941) might suggest.

What I offer today, on the Boy Wonder’s birthday, is a consideration of that movie from an unusual angle looking not just at its originality but also at its shrewd consolidation of a variety of techniques.

Wellesapoppin’

We’re so used to considering Kane powerfully original that it’s worth remembering that it synthesizes a lot of traditions. I’m not thinking of Pauline Kael’s claim that it’s a culmination of the 1930s newspaper genre; as so often, she fails to persuade me. I’m thinking instead of the look and sound of the movie, as well as its storytelling strategies.

Depth staging and deep-focus cinematography are two techniques not always kept distinct in critical discussion. 1930s Jean Renoir films have plenty of depth staging but usually not so much deep focus. Citizen Kane won attention partly because it has plenty of both, and in exaggerated form. The figures often stretch very far back, someone or something is often rather close to the camera, and often all of them are sharply focused.

Without taking anything away from the boldness of Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland, we should recognize that they reworked visual patterns—what I’ll call schemas—that were already circulating in filmmaking. Framings with big foregrounds, distant planes, and low angles weren’t unknown in silent films (Opium, 1919; Greed, 1925; A Woman of Affairs, 1928) and some early talkies (No Other Woman, 1933).

There was a sort of fad for such deep staging, especially with wide-angle lenses, during the late 1930s, though all the planes weren’t usually kept in focus. Some directors, such as John Ford (here and here) and William Wyler, favored deep images, while art director William Cameron Menzies (see here and here) made them part of his artistic signature. Below: Ford’s Long Voyage Home (1940), shot by Toland, and Menzies’ Our Town (1940), directed by Sam Wood.

It’s now acknowledged that many of Kane’s deepest shots weren’t actually made in the camera, but by means of special effects, particularly matte shots. Interestingly, this too wasn’t utterly original; compare the composite shot from Kane with the one from Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935), which has an even more aggressive foreground.

Welles and Toland called attention to these techniques by a radical gesture: many of these deep shots are long takes from a fixed camera position. Most filmmakers who used these depth schemas inserted them into passages of orthodox scene dissection. The depth shots might establish a locale, or they might be inserted into a series of analytical cuts, or they might be part of a shot/ reverse shot pattern. But in Kane you’re forced to notice the Baroque plunge of space because the lengthy take rubs your nose in the flashy composition.

It’s clear that Kane crystallized a certain look that was picked up by John Huston, Anthony Mann with or without his DP John Alton, and many other directors. The Welles/Toland version of depth consolidated a visual style that dominated American black-and-white filmmaking into the 1960s. Typically, though, filmmakers didn’t rely on the fixed long take as much as Welles did in Kane. Even Welles gave up that option in favor of dynamic editing of deep-focus shots, as in The Lady from Shanghai (1948) and Othello (1952/1955).

Not everything is long takes and depth. The pictorial variety of the film is, I think, unprecedented. The “News on the March” sequence becomes a virtuoso exercise in all the techniques that the rest of the film won’t be using. For perhaps the first time in history, Welles artificially distresses his staged scenes to make them match archival footage. He adds scratches and light flares.

This newsreel is so film-savvy that it can build in jump cuts and fast-motion as guarantors of fake authenticity. One passage mimics two-camera reportage, allowing us to imagine paparazzi crouched and perched at a fence to grab clandestine shots of an elderly Kane.

Here the schemas that are borrowed come from archival and documentary traditions, repurposed to add realism to this fictional biography. Welles, as we’ve seen in the Great Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here), was a smart-alec cinephile: your disobedient servant.

What about sound? Back in 1994, Rick Altman wrote a pioneering article showing how Kane manipulates our sense of auditory space, and he connected that to Welles’ use of radio conventions. Contrary to what we might expect, Welles’s soundtrack doesn’t create much “deep-focus sound”; Altman shows that our impression of that is created chiefly by an overall reverberation rather than precise placement of sonic events. Altman also stresses Welles’ use of sudden, loud sound events to start or end a scene–another radio technique.

Today we’re lucky to have a great many of Welles’ radio programs available on the Web, and we can appreciate how his rich soundscapes mingle noises, dialogue, and voice-over narration. These shows remain very gripping. Listening to Kane in the same spirit, I’ve been impressed with how talky it is, how sounds crash in on you, and how even bursts of silence can be startling. Welles told one biographer that he aimed to create spiky transitions, both visual and sonic, because he thought most films of the period were dull.

He had already made his stage reputation on “shock effects,” those stunning high points in particular productions: the death of Macbeth in the Harlem production (1936), an actor’s headfirst tumble into the orchestra pit in Horse Eats Hat (1936), the mob’s murder of Cinna the Poet in Caesar (1937), the guillotine scenes in Danton’s Death (1938), and police agents firing from the audience in Native Son (1941). He became known as a director of thrilling moments, ever willing to sacrifice steady buildup to anything that would astonish. Forties theatre critics had a name for it: “Wellesapoppin’.” That quality dominates Kane’s images and sounds.

Remembering, recounting, replays

Otto Hullet, Barbara O’Neill, and Orson Welles in Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936).

Just as Kane amplifies visual and auditory schemas already in circulation, the film does somewhat the same thing to narrative strategies. The key innovation here involves flashbacks and point of view.

Flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but the early 1940s began a flashback craze that continued throughout the decade. Between August 1940 and December 1941, every top studio tried out flashbacks in a major release: The Great McGinty (Paramount), Kitty Foyle (RKO), I Wake Up Screaming (Fox), H. M. Pulham, Esq. (MGM), and Strawberry Blonde (Warners). A reviewer claimed that the “retrospective viewpoint” technique in A Woman’s Face, released the same month as Kane, “had of late become commonplace.” By September 1941 the Los Angeles Times critic considered the technique overused.

Even though the trend was already launched, Kane probably strengthened Hollywood’s inclination toward time-shifting. Again, it crystallizes in an influential way possibilities opened up in film, radio, theatre, and other media.

Kane’s central premise—a dead man recalled by one or more survivors—had been rehearsed in earlier films. The Power and the Glory (1933), scripted by Preston Sturges, was probably the most noted experiment in that vein. (For more, see this long-ago entry.) Another example was The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), which begins with a funeral procession and flashes back to the start of a backstreet love affair. (See this entry.) The Escape (1939) centers on a doctor who tells a crime reporter about a recently deceased neighborhood gangster, and flashbacks enact his tale.

These earlier examples stick to a single teller, while Kane offers reports on its dead man from five characters. Here again, however, there are precedents. In fiction and drama, trials have long served as motivation for flashbacks from multiple viewpoints. A major example, perhaps the first, is Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). Multiple tellers recounting events in flashback were staples of Hollywood courtroom dramas too. Beyond the trial-based format, Welles’ radio programs had welcomed multiple storytellers, sometimes embedding them within one another’s tales, sometimes letting them banter with each other.

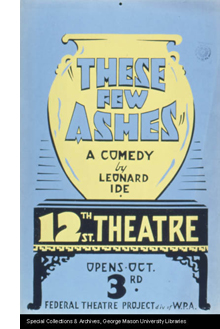

Kane assembles views on a person rather than evidence of a crime, but even this is not completely unknown. Some playwrights had tried out what Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz had called the “prismatic” approach to an absent central character. Sophie Treadwell’s play Eye of the Beholder (1919) portrays an offstage woman as seen through the eyes of her former husband, her lover, her lover’s mother, and her own mother. The play These Few Ashes (1928) presents the life of a (supposedly) dead roué through the recollections of three women, each of whom sees him quite differently.

Then there’s reporter Thompson’s investigation. The Power and the Glory’s exhumation of the tycoon’s past is presented simply as his old friend’s recounting; it’s not the investigation of a mystery. Kane innovated in the biographical film genre by creating curiosity based on the dying man’s last word, “Rosebud.” That device shifts us to the terrain of the detective story. The dying message had become a mystery-tale convention from Conan Doyle onward, and Welles and Mankiewicz shrewdly recruited it for their purposes (although it’s not clear exactly who hears Kane say the crucial word).

In blending conventions of several genres, Kane motivates the flashbacks on diverse grounds. The film’s detective-story side is anticipated by The Phantom of Crestwood and Affairs of a Gentleman (1934); in both, flashbacks represent the suspects’ answers under questioning. Like The Escape, Kane uses a reporter’s search for a story to justify its flashbacks, and the reporter isn’t the protagonist (as he’d be in a typical newsman movie). And being something of a biopic, Welles’s film can trace the rise of a great man from the vantage point of old age, as in Edison, the Man (1940). By the way, that’s another film of the era using a journalist’s questioning to launch flashbacks to a person’s life.

Another wrinkle: Kane’s flashback organization skips around in the past. Episodes of Kane’s life are not presented in 1-2-3 order. Plays set in courtrooms, such as Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), had rendered flashbacks out of sequential order, and so had radio dramas. Welles’ 1938 radio adaptation of Dracula shuffles episodes in the manner of the source novel. Non-chronological strings of flashbacks weren’t common in film, but The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932) and The Power and the Glory used them significantly.

Even rarer is the replayed flashback, the scene from earlier in the film that is repeated, usually to reveal something we hadn’t caught on the first pass. Kane has occasion to present a brief replay from differing character viewpoints. Susan’s opera premiere is first treated curtly, as the object of the stagehands’ scorn. Later, in her flashback, the same scene registers the central characters’ reactions: a severe Kane, a bored Leland, the harried singing master, and above all the panicked Susan.

Replay flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but The Witness Chair (1936) provides one example. After Kane, they would become more common, with Mildred Pierce (1945) offering one of the period’s most complex examples. (I discuss it here and here, with a video here.)

Even the coup de théâtre of following Kane’s death with a newsreel can be seen as revising a schema. “News on the March” isn’t exactly a flashback, but it provides exposition by shuttling among time periods in a manner characteristic of the film to come. Projected headlines and documentary footage, faked or actual, had found their way into 1930s theatre practice, notably in the WPA Living Newspaper productions. Many 1930s films opened with montage sequences using headlines, stock footage, and voice-overs like those in newsreels; The Roaring Twenties (1939) is a bold example. Gabriel over the White House (1933), with its mix of library footage and staged shots, anticipates Kane somewhat, as does Welles’ script for an uncompleted 1939 RKO project, The Smiler with a Knife, which includes a newsreel surveying the career of the fascist villain.

Another, less proximate source may be Sidney Kingsley’s 1936 Broadway play Ten Million Ghosts. This strident antiwar tract lasted only eleven performances and was never published; I took a look at a copy of the script last week. In the original production Welles played the naïve young poet André in love with the daughter of a munitions magnate during World War I.

Ten Million Ghosts includes a scene in which arms makers spend an evening watching a battlefront newsreel in their parlor. Kingsley’s purpose is to show the capitalists as utterly indifferent to the slaughter that the camera records.

They watch in silence for a while. Then there are technical comments on the explosives, shells, etc. as we see them hurl geysers of earth and men into the sky.

Was this embedded newsreel an early source for News on the March? Scholars have wondered. And there’s more.

As the film unwinds, André, who has learned that his family has been killed in the war, cries out in protest. Madeleine is torn between him and her father. To win her over her father angrily defends his double-dealing between both sides in the war. It’s all just business, he insists. Then we get this piece of action:

De Kruif rises, intercepting the beam of the projecting machine, his face highly lighted, his shadow, black and ominously magnified, thrown on the screen superimposed over the pictures of men writhing in bloody destruction.

Was De Kruif’s moment in the play a visual idea that inspired Kane’s projection-room scene? If so, Welles and Toland revised the premise of the play. Instead of the rather obvious looming shadow cast on the screen, the story editor is a silhouette against the blank white rectangle, and then, in a reversed setup, he becomes another silhouette, this time splitting the projector beam.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that he never saw the projection scene in Kingsley’s play because he was always back in his dressing room at that point. But as Pat McGilligan points out in his new biography Young Orson, Welles could hardly have been unaware of the film-within-the-play; many critics commented on it. More decisively, in the playscript, André is clearly onstage during the screening. He cries out against the carnage: “Look, look! Those are only pictures. . . Out there it’s real. . .” Peter Noble’s 1956 biography The Fabulous Orson Welles quotes Welles as declaring that this scene left a strong impression on him.

It’s not enough just to mention some sources. If you practice historically-slanted criticism, you need to ask not only “Where from?” but “What for?” In other words, you have to ask how elements that a filmmaker inherits get repurposed for the particular movie.

So, for instance, Kane’s depth-designed images held in long takes allow a more “theatrical” shift of attention within a visual field (driven largely by following who’s speaking). They also create contrasts of scale and visual weight. And each scene will have its specific demands that the depth technique fulfills. A depth shot can present cause and effect in the same frame, and it can build suspense by letting us await Kane’s interference in a foreground situation.

Similarly, Kane’s narrative strategies, synthesizing so many earlier efforts, blend to create a mystery that isn’t about whodunit but rather “why’d he do it?”

I’m not exactly saying that everything is a mashup. But that slogan does capture the fact that in art nothing comes from nothing. Kane blends several options that had been circulating in popular culture and high culture for some years. Like others before and since, Welles revised schemas tried out earlier; he combined some, exaggerated some, and infused many of them with new force. Because of his film’s prestige, he gave thrusting imagery, bold sonic manipulations, and complicated time shifts a new prominence in Hollywood filmmaking. The Forties had begun.

There are a several essential Welles sources. Apart from the many fine critical studies (see especially Jim Naremore’s Magic World of Orson Welles and Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?), the biographical surveys I habitually turn to are Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles (Da Capo rev. ed., 1998), with a painstaking chronology by Jonathan Rosenbaum; the three-volume Simon Callow biography; Bret Wood’s Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1990); Barbara Leaming’s Orson Welles: A Biography (Viking, 1985; my reference to shock effects is from p. 338); Frank Brady’s Citizen Welles (Scribners, 1990); and most recently Pat McGilligan, Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane (Harper, 2015). Pat’s discussion of Ten Million Ghosts is on pp. 366-367; Welles’ misremembering of the production is on p. 78 of This Is Orson Welles. A typescript of Kingsley’s play is held in the New York Public Library, at the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts.

Rick Altman’s study is “Deep-Focus Sound: Citizen Kane and the Radio Aesthetic,” Quarterly Review of Film & Video 15, 3 (1994): 1-33. If it’s available without cost online, I haven’t found it. The programs “Dracula” (1938), “The Hurricane” (1939), and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” (1940) provide vivid examples of multiple narrators and embedded flashbacks. For a comprehensive account of Welles’ radio work, see Paul Heyer, The Medium and the Magician: Orson Welles, the Radio Years 1935-1952 (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005). As for prismatic flashbacks, in the mid-1930s, Mankiewicz had built the plot of an unfinished play around the memories of people who had known John Dillinger. See Richard Meryman, Mank: The Wit, World, and Life of Herman Mankiewicz (New York: Morrow, 1978), 247, 258.

On Kane‘s visual style and its place in film history, see my accounts in The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1997), as well as on this site (here and here especially). A detailed analysis of Kane‘s narrative strategies is in Chapter Three of Film Art: An Introduction, 11 ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2016). The distinction between depth staging and deep cinematography is explored in Chapters Four and Five.

Rhapsodes on a roll

Key Largo (1948).

In the last week or two, my new book The Rhapsodes has been lucky enough to attract attention. There are now four reviews: one by Geoffrey O’Brien in the print edition of Artforum; another by Nick Pinkerton in the print edition of Sight & Sound; one online by Michael Philips of the Chicago Tribune; and one online by David Hudson, head wrangler at Fandor. All were more generous than they needed to be, although how could I lose by quoting Ferguson, Agee, Farber, and Tyler? These guys carried me. There are some quotes from the reviews at the University of Chicago Press site.

In addition, the Library of America has run a Q & A with me about the relevance of my four critics to movie criticism today. Thanks to Jeff Tompkins for handling this.

Coming up, here in NYC:

*An evening of discussion and book-signing at Videology at 7 PM on 9 June!

*Screenings of four films related to the book at the American Museum of the Moving Image, 25-26 June!

Thanks to Erik Luers of Videology and David Schwartz of MoMI for arranging these events. If you’re in the neighborhood, why not drop by?

P. S. 6 May: Thanks to Fiona Pleasance for updating my S & S link.