Terence Davies: Sunset songs

Wednesday | May 11, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

Sunset Song (2015).

DB here:

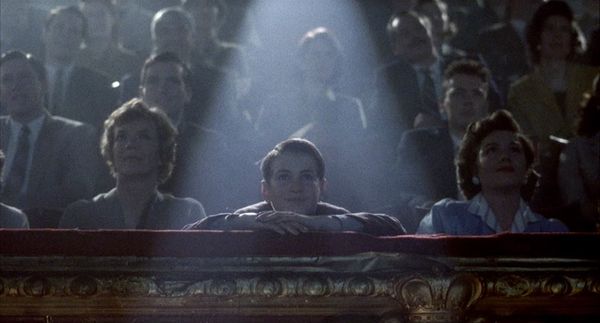

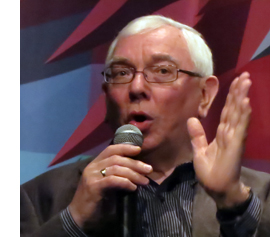

A career retrospective brought director Terence Davies to Astoria’s always enterprising Museum of the Moving Image. On Sunday MoMI ran a handsome 35mm copy of The Long Day Closes (1992), introduced by Sony Pictures Classics Co-President Michael Barker (who originally distributed the movie). The film was followed by Davies’ informative discussion with Michael Koresky, author of a fine critical study of Davies. On Tuesday, there was an avant-premiere of Sunset Song (2015) with Agyness Deyn, the principal player, joining Davies and Koresky. The first screening featured one of the greatest films of the 1990s, while the second showcased the literary adaptation that Davies had sought to make for several years.

The two evenings left me with renewed respect for the power of this audiovisual art we call cinema. They also set me thinking about Davies’ unique contributions to that art, particularly in his first two features.

MGM in Liverpool

The Long Day Closes.

If you needed proof of the unpredictable, zigzag influence of Hollywood cinema, look no farther than the films of Terence Davies. When he saw his first film, Singin’ in the Rain (1952), he knew utter rapture, and his early years were illuminated by visits to the local movie house. But unlike other cinephile directors, he didn’t turn retro. His first two masterpieces, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992), decant the splendors of American musicals into vessels more severe and melancholy. The brooding lyricism of these films, presented in a stringently geometrical pictorial style, makes them almost unrecognizable cousins of the 1950s films that nourished him.

Davies understood, as so many postwar critics of mass culture didn’t, that Hollywood, for all its formulas and conventions, captured genuine feeling; indeed, those very formulas and conventions released that feeling. In Davies’ hands, however, the feelings gain a rougher texture. In tales of patriarchal power and everyday betrayals, echoes of the yearning of Judy Garland and the vibrato of Doris Day seem distant and distorted. Davies finds the evanescence hidden in Yankee exuberance, and he takes it very personally.

That’s partly because popular song is filtered through a sensibility deeply committed to classical musical expression. Nobody but Davies would accompany an image of urban squalor with the arching final melody of Vaughan Williams’ Pastoral symphony, or the soft run of George Butterworth’s “Shropshire Lad” tune over the tan rug in The Long Day Closes. The soaring Barber violin concerto accompanies, for an astonishing eleven minutes, the opening images of The Deep Blue Sea (2011); it’s practically a cinematic tone poem. One of those directors who’s unthinkable outside the sound cinema, Davies dissolves any barrier between popular song and art music. The American Song Book, he says, is the country’s greatest gift to the world, and Stephen Sondheim is our Schubert.

Music is tied, in intricate ways, to family. These films are openly autobiographical. The first part of Distant Voices is a terrifying portrait of domestic life with a madman; the second part treats the radiant moments without him. The father is absent in The Long Day Closes, and so life in the household, with Mum and brothers and sister and visiting chums, is blissful. (Surely Davies is the great filmmaker of sibling devotion.) Now the threat lies beyond the threshold; school bullies, sadistic teachers, and a Church that seems indifferent to the suffering of a boy vaguely sensing his homosexuality.

Yet by a kind of benevolent contagion, the joy of American cinema transfigures the grubby side of daily life–through communal singsongs in parlor or pub, through impromptu performances at parties, through hit-parade tunes hummed during daily routines. There are line-readings too; in The Long Day Closes the Boccherini minuet from the ball in The Magnificent Ambersons is matched by quick borrowings from Welles’ voice-over narrator. In one of the great sequences of modern cinema, a survey of the boy Bud’s world is shot from straight-down framings that roll by like scenes in a picture scroll. Birds’-eye views of street, cinema, church, and school are wrapped in the throbbing voice of Debbie Reynolds singing “Tammy.”

Cinema wins on the soundtrack. Take away the music and the snippet from Kind Hearts and Coronets and you have a grim topography. With movies, life’s miseries become bearable.

Chamber pieces

Distant Voices, Still Lives.

Distant Voices and The Long Day Closes balance social realism with a first-person quality shot through with feeling. Davies remembers everything about his childhood, and he can present unsentimentally the gray-brown wallpaper and the bulky furnishings. (He remarked that period films always forget that people didn’t have the most up-to-date things; nobody in 1950 Liverpool owned 1950 furniture.) Even realistic detail is saturated with memory and expression. Similarly, Davies’ reliance on planimetric shooting, dominant in Distant Voices and still strong in The Long Day Closes, creates at once rigid formality and a curious intimacy, as if we were looking at family portraits.

When capturing moments of serenity, the perpendicular shots evoke utter honesty; characters face us frankly, hiding nothing. But confronted with a schoolyard beating or a psychopath thrashing his wife, this curiously impassive camera–no wild handheld bursts or jagged cutting–only accentuates the pain. The camera’s unearthly calm takes on a kind of ruthlessness, as if nothing awful that happens in this world can make it flinch, just as nothing rapturous can make it go giddy. Davies seems fairly Wordsworthian: his poetry is “a spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling,” but the overflow is “recollected in tranquility.” The scene’s situation and the music, we might say, supply the feeling, while the framing supplies the tranquility and suggests the distance of memory.

These tableaus remind us that Davies is one of the few masters of cinematic chamber art. The exteriors, very few in these two features, are treated in the same rectilinear framings as the rooms are, as if one could never escape the carpentered contours of a house. More often, we’re indoors, and the human figures in are caught, nearly frozen, in a parlor or kitchen or hallway or schoolroom. No wonder his favorite painter is Vermeer.

Like Dreyer, Davies finds drama in the nearly closed room, the space slashed by light and opening onto somewhere else: in Davies’ case the doorway and the stoop and the street. These are the little theatres of human relaxation, of sharing, good times, and of course song. All the more jolting, then, when the father in Distant Voices turns up at the door, released from the hospital, or when Bud in The Long Day Closes sees his pal Albie go off to the pictures without him. As Michael Koresky notes in his book, the face at the windowpane looking out at the world is a recurring image for Davies: the edge between two arenas of experience, both harboring pain and exaltation.

Davies is famous for laying out each film with a draftsman’s precision: shot by shot, line by line, musical extract by musical extract. These films are absolutely through-composed. Their strict rhymes channel the feelings of the characters–or rather, the feeling of a scene as a whole–into determinate shapes that we can grasp. The sound is as important as the images; Hollywood musicals taught him the tight coordination of image and phrasing that pattern his song sequences and pictorial cadenzas.

Davies is famous for laying out each film with a draftsman’s precision: shot by shot, line by line, musical extract by musical extract. These films are absolutely through-composed. Their strict rhymes channel the feelings of the characters–or rather, the feeling of a scene as a whole–into determinate shapes that we can grasp. The sound is as important as the images; Hollywood musicals taught him the tight coordination of image and phrasing that pattern his song sequences and pictorial cadenzas.

No surprise, then, that Davies loves music and poetry, to which he constantly compares cinema. And no wonder he admires T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, that poem that takes its title from chamber music. In both music and verse, powerful feelings flow through rigorous forms. The chock-a-block construction of Distant Voices sets up poetic parallels and contrasts between the two parts. More boldly, The Long Day Closes offers a narrative that’s barely there: a suite of situations, a flow of anecdotes that gathers symphonic force. It recalls Pather Panchali and other films about a child coming to understand that whatever happens, painful or exhilarating, is transitory when seen against the backdrop of eternity.

Davies is after, he said in conversation, “the intensity of the moment,” and what happens before or after may seem of little account. Sound, light, color, movement: all become focused on the poignancy of the felt instant. Yet in another echo of Romanticism, that instant isn’t trivial when it’s seen in a cosmic context. Left alone by his brothers and sister, Bud thrusts his flashlight to the sky, creating a movie-projector’s beam as a demonstration that light goes on forever.

In an echo of this moment, Bud’s long days close with a merger of the momentary and the infinite. Two boys sit (in the balcony?) poised against the sky. Their movie becomes a majestic sunset, wrapped in the plangent song that gives the film its title. The light from the stars dates from Jesus’ day, Bud tells Albie, as the sacred chambers of his world open onto the universe.

Daughter of the earth

Terence Davies and Agyness Deyn.

A sadistic, baleful father; a mother bearing the brunt of his demands; a brother and sister as tender with one another as sweethearts; gentle friends who sustain the household with music–with Sunset Song we seem to be back in the world of Davies’ early films. But instead of the grubby city streets we’re in a glorious green-gold landscape of rolling fields, and instead of postwar London we’re in Scotland on the eve of World War I.

Sunset Song, drawn from the 1932 novel by Lewis Grassic Gibbon, exemplifies Davies’ later interest in adapting literary works (The Neon Bible, 1995; The House of Mirth, 2000; The Deep Blue Sea). In all of these, Davies tries to respect the spirit of the original while finding affinities with his own sensibility.

Sunset Song centers on Chris Guthrie, the dutiful daughter of a farm household. For the early stretches of the film she’s a cautious observer, but her voice-over, presented in the third person and past tense, prepares for her to take over the action. At first she’s inclined to run away with her brother, but duty keeps her home. When she comes into ownership of the farm, she realizes that she is rooted in the place. The earth, more eternally solid than sea or sky, gives her strength. If she cannot forgive what her father has done, she can learn to understand and forgive another man’s betrayal.

At first glance, we might seem to be snugly settled in British Cinema of Quality. But Davies has always made “costume pictures,” and his take isn’t in tune with Masterpiece-Theatre fashion shows. The clothes, as Davies always demands, look lived in, worked in, slept in. Agyness Deyn explained that for wardrobe they gladly took the worn leftovers of tonier productions.

Despite the eye-filling landscapes shot in 65mm, Davies hasn’t played false to his intimate aesthetic; this remains a chamber drama, with few primary characters. Like Bud in The Long Day Closes, Chris is our focal consciousness; apart from a substantial flashback to war-torn France, we’re confined chiefly to what happens around her. A few years of history unfold in a rhythm tuned to her growing awareness of her options and decisions, good and bad.

The style is far more mainstream than in the first two features. We get continuity editing (often in its constructive vein), smooth reframings as actors move around sets, and not many images recalling the tableau-vivant look of the earlier work. Chris is introduced in one of those twirling camera movements that are de rigueur nowadays, though Davies refreshes the convention by the visual metaphor of her rising up from the wheat, as if from sprung from the soil, and tipping her face to the sun, like a flower.

But Davies insisted on both evenings that for him, form springs from content. I take that to mean that the brick-by-brick shot assemblage of the first films suits the episodic, memory-driven nature of those tales. Here we have a novelistic saga (the original book is part of a trilogy), and so we must stay engaged with a chronologically unfolding plot. Davies has opted for less stylization, the better to rivet us to the powerful story of his protagonist’s blossoming to maturity.

Again, music yields a model. He urges young filmmakers to study symphonic cycles, like those of Bruckner and Sibelius, in order to appreciate scale and balance and variety in a large-scale structure. The relaxed flow of Sunset Song–and what power the title must have had for him–is like that of a full-scale orchestral essay. If Distant Voices, with its shifting, decentered viewpoint, is a chamber piece and The Long Day Closes is something like a song cycle for voice and quartet, this latest work is perhaps a concerto, with Chris’s sturdy presence an instrument of commanding range set against the massive landscape and a choir of family, friends, and neighbors.

Normally we must wait years between Davies’ films, but A Quiet Passion, his biography of Emily Dickinson, is beginning its career in worldwide distribution now. One feature in 2015, another in 2016. “I’m in danger of becoming prolific.”

Back in 2001, Kristin and I met Terence and his assistant John Taylor (loyal Packers fan) at Belgium’s summer film college. They were good company then, and still are. The MoMI screenings provided a wonderful occasion to see them and the films once more. If you’re in the vicinity, start queueing now for the follow-up items in the series. And Sunset Song opens this Friday at Film Forum, with Terence present. From there it will make its way across the US. You couldn’t spend your time more fruitfully. These movies will last a very long time.

Thanks to David Schwartz and his colleagues at MoMI. The Long Day Closes is available on DVD and Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection; thanks to Kim Hendrickson for her assistance. And thanks to George Nicholis of Magnolia Pictures, which is releasing Sunset Song.

For more on the stylistic tradition that early Davies films work within, you can consult Chapter Six of On the History of Film Style and these entries.

The Long Day Closes (1992).