Archive for July 2016

Frodo lives! and so do his franchises

Given the saturation of fantasy, sci-fi and superhero films we experience today, not to mention how frequently we quote from Lord Of The Rings, it bears reminding now and again (not too obsessively, mind) just what a game changer Lord Of The Rings was.

Jordan Adcock

Kristin here:

A little over ten years ago, in April 0f 2006, I finished the manuscript of The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007). Given that I had previously written books and essays on films by such auteurs as Sergei Eisenstein, Jacques Tati, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Renoir, and Robert Bresson, those who knew my work were perhaps bemused by this change of direction.

I had decided to tackle this project, which proved to be an enormous but richly rewarding one, in 2002, after the release of the first part of The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring (December, 2001). Already it was apparent to me that Peter Jackson’s adaptation would be an enormously influential film, to the point where, whether or not one likes the movie itself, it would be among the most historically important films ever made. New Line used the internet to promote it at a time when it was still not common for a film to have its own studio-created website. The cooperation between the filmmakers and the video-game designers was unprecedented. The extended-version DVD releases, arriving only five years after the introduction of the format, had unique depth and breadth. The impact of its technical innovations, particularly in digital special effects and color grading, was enormous. The film’s success boosted the many independent producers around the world who had largely financed it. Not to mention the ways in which the movie transformed New Zealand through tourism, a small but sophisticated and thriving film industry, and a surge of national pride. The film and the franchise impacted the Hollywood industry in almost any way one could imagine.

In 2002, to believe all of this was going to happen and to commit to spending time, money, and effort in researching all these topics required something of a leap of faith. It was one I was confident in making. Uncharacteristically for a historian, I made some predictions about the lasting power of LOTR and its franchise. This risk was inevitable, given that I was writing about a lengthy ongoing event, one which clearly would last far into the future. The book begins: “The Lord of the Rings film franchise is not over, not will it be for years.” [p. XIII] Later I specified:

The franchise is not nearly over. Middle-earth-themed video games continue to appear. Additional licensed toys and collectible items are still being brought out. Fan activity remains lively in cyberspace and the real world. The phenomenon has reached into international culture in ways that go far beyond the commercial confines of the franchise. Politics, education sports, and religion all reflect the influences of the film. An extinct race of tiny people discovered on a Pacific island was instantly dubbed “hobbits” by headline writers and even the scientists who discovered them. [pp. 9-10]

I was reminded of these claims by two recent events. First, last week’s Comic-Con included, as usual, a Weta Workshop booth, and, as usual, several of its popular limited-edition collectible figures from LOTR were debuted there. Second, on June 23, Jordan Adcock posted an intriguing article, “Can fantasy films escape Lord of The Rings’ shadow?” on Den of Geek. Yes, thirteen years after the release of The Return of the King (December, 2003) and ten after I ended the coverage in my book, the franchise goes on, as does the influence of Peter Jackson’s film. The number of products and tie-ins is far smaller than at the height of the films’ releases, but it seems to have settled down to a steady flow.

This combination suggested that it is an opportune time to point out that this film is still influencing the fantasy genre–perhaps too greatly–and that its franchise, though reduced, rolls on. I don’t think I was being terribly prescient in predicting all this, but it’s a bit of a relief to find out that I was right.

Collectibles, video-games, and more

Fans and collectors continue to purchase LOTR studio-licensed and fan-generated items of all sorts. Some of these are from the era of the film’s release, and some are new. A search on “Lord of the Rings” in the collectibles category on eBay generates 13,476 items, only a small percentage of which are related to products relating to the novel’s franchise or that of the 1978 Ralph Bakshi film. Some of the upscale and/or rare items sell for hundreds of dollars. There is still a demand.

In my book I made no effort to catalog all the products made to that point. In fact, I don’t think it would have been possible, unless I had had access to New Line’s records of its licensing contracts. Besides, that wasn’t part of the purpose of the book. In discussing licensed products, I was more interested in digital technology had affected what sorts of items were made. There was the motion-capture for the video games, for example. There were the DVDs–a format introduced as recently as 1997, the year when Miramax signed a contract with Saul Zaentz, thus obtaining the rights for Peter Jackson to make LOTR. (In Chapter 7 I give a little history of the introduction of DVDs and the part LOTR played in the studios efforts to move from rentals to purchases of home video.) There was the facial scanning of the actors for the action figures. There was, however, a dizzying array of hundreds, or more likely thousands of other, more conventional products licensed around the world. I once bought a lottery ticket in London not because I hoped to win a prize but because it was LOTR-themed and had a picture of Elijah Wood as Frodo on it.

Here I just want to give a few examples to show that New Line-licensed products are continuing to appear. I won’t include any Hobbit-based licensed products except in passing. Obviously the second trio of films extended the original franchise, but here I am only concerned with the longevity of the LOTR’s ability to generate more products and to influence the fantasy genre.

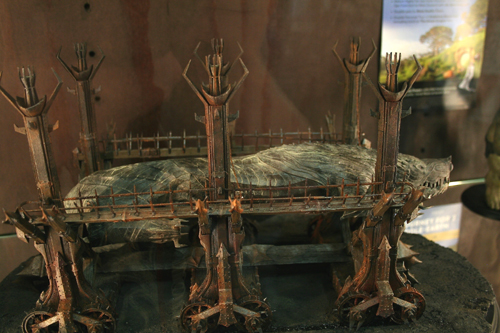

I mentioned the Weta Workshop collectible figures, which continue to be among the most popular products among devoted fans. The main fan-site, TheOneRing.net (Disclosure: I am a member of the staff) annually posts a video tour of the Weta booth at Comic-Con. This year’s video, Collecting the Precious-Weta Workshop Comic-Con 2016 Booth Tour (by TORn staffer Josh Long, about 18 minutes), lovingly moves over the glass cases containing the new items, including statues of Lurtz and Boromir enacting the latter’s death scene late in Fellowship. There’s also a big piece with the battering-ram, Grond. (I have a sentimental attachment to Grond, since it was the only one of the large miniatures made by Weta Workshop that I saw during my 2003 tour of facilities at Stone Street Studios. See above for the miniature version of the minature.) In watching the video, I didn’t keep count, but although over half of the figures are from The Hobbit, there are quite a few LOTR ones as well.

I have lost track of all the Middle-earth-based video games that have appeared since the last one the book covered: “The Battle for Middle-earth” (released on December 6, 2004, and, as far as I can tell, still in print). It was the fourth, and the first to concentrate on battles and strategies rather than on the plot of the movies themselves. By now here have been 22 of them, according to the “Middle-earth in video games” entry on Wikipedia, the most recent being “Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor” (2014). Its action takes place between that of The Hobbit and of LOTR. The total given above includes “Lego The Lord of the Rings.”

Lest one think that the only products are expensive ones aimed at the most enthusiastic core fans and dedicated gamers, I should mention that there are less pricey items. Inevitably, given the recent fad for adult coloring-books, there is one based on LOTR, list price $15.99, released May 31 of this year. (See top.) I expect a Hobbit one will follow. Warner Bros. has continued to bring out a film-based LOTR wall calendar each year. You can already pre-order the 2017 one, due out on September 15.

The posthumous career of J. R. R. Tolkien

As I pointed out in The Frodo Franchise, there has long been a franchise based around Tolkien’s original novels, which I discussed briefly. Lest we think that the film franchise must inevitably fade, it is worth noting that HarperCollins, Tolkien’s publisher, has kept the novel-based one going for decades after the author’s 1973 death.

There are, for example, numerous games like “The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game” (judging from the comments on Amazon, this must have appeared in 2013). HarperCollins publishes its own calendar, based on Tolkien’s work as a whole rather than just LOTR. Many do center on LOTR, often featuring the work of a major Tolkien illustrator. With The Hobbit having been published in 1937, however, its 80th Anniversary is being featured for 2017, also available for pre-order.

The Tolkien-based franchise items tend to be somewhat more dignified than many of the film-derived ones. This is especially true given that many of the products consist of new or reissued works by Tolkien.

Non-fans of the books may not be aware that the Tolkien publishing juggernaut goes on as well. These are not all cobbled-together variants of existing Tolkien works. Actual new texts by him appear at intervals as his son Christopher Tolkien slowly releases editions of unfinished manuscripts by his father. By now Tolkien has far more literary works published posthumously than during his lifetime, even if one does not count Christopher’s epic assemblage of the drafts for LOTR in the twelve thick volumes of “The History of Middle-earth.” (Tolkien was a notorious non-finisher and left behind many incomplete academic manuscripts as well.)

Earlier this year there appeared The Story of Kullervo, retold by Tolkien from the Finnish epic The Kalevala. Amazingly, a second is due this year: The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun (out November 3). These poems, both with historical and formal analysis by notable Tolkien scholar Verlyn Fleiger, are not for the broad audience of Tolkien fans, but they obviously generate enough interest among core devotees and scholars to be worth publishing.

Tolkien was a talented amateur artist who occasionally illustrated his own work, most notably The Hobbit, and drew many sketches and maps to help him visualize Middle-earth. The ones for LOTR were published last October as The Art of The Lord of the Rings.

There are also, of course, as many different new editions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as the publishers can possibly justify in some fashion. Every now and then a “gift edition” with new illustrations appears. The one tied to the 80th anniversary of The Hobbit is a version illustrated by Jemima Catlin, announced for early next year. On September 22, the long-delayed facsimile of the first edition of The Hobbit is due to appear. (As I recall, it was originally supposed to be part of the 75th anniversary celebration.) This facsimile is of considerable interest to fans and scholars alike, since Tolkien revised portions of the original tale. Most notably, it contains a very different version of the famous riddles scene between Bilbo and Gollum, in which the Ring is introduced in a way completely incompatible with the premises concerning it established later by Tolkien in LOTR.

Even bits of film and audio recordings of Tolkien occasionally resurface. On August 6 at 8 pm London time, BBC Radio 4 will broadcast of “Tolkien: The Lost Recordings.” This program is based around some newly rediscovered audiotapes of outtakes from the BBC’s 1968 documentary, Tolkien in Oxford.

Fantastic stories and where to find them

Jordan Adcock’s “Can fantasy films escape Lord of the Rings‘ shadow?” was inspired by the release and failure of Warcraft: The Beginning. He uses the occasion both to explain why the Jackson’s LOTR trilogy so dominates conceptions of filmic fantasy and to suggest how Hollywood might make films that won’t be compared to it and inevitably found wanting.

Alcock largely credits the film’s lingering impact to the depth and plausibility of its visual rendering of Tolkien’s invented world, Middle-earth. He spends some time describing how Tolkien, with his brilliant command of history and ancient languages, managed across his lifetime to develop a consistent, appealing continent with different races, languages, countries, and landscapes, as well as its own history. Jackson’s film manages to create “a fantasy world with both digitally-aided grandeur and a practical, lived-in feel […] Jackson recreates Tolkien’s precision of time and setting.”

Certainly the film’s production design, its New Zealand locations, and its cinematography creates a Middle-earth that impressed even the film’s harshest critics. Its treatment of the plot and characters, though less successful overall, stuck far closer to the novel than did the more recent Hobbit trilogy. (See here, here, here, and here for my comments on the strengths and failures of the three parts of the latter.) Long-time fans like me forgave LOTR a lot, including added schoolboy humor and Arwen supposedly dying, for the visuals and the music and the near-perfect casting. And, as David, who has never read Tolkien, remarked to me when we walked out of theater after his first viewing of Fellowship, “Well, it’s better than Star Wars!” Within the fantasy genre, LOTR probably is the finest achievement in modern American moviemaking. It is no wonder that subsequent films, even twelve years later, are seen by critics either as pale imitations of it or as failed attempts to create a different but equally dense and coherent fantastical world.

Alcock’s hints at how filmmakers might avoid such problems, but in the process he also admits that his solutions are nearly impossible to achieve. First, he points out that the fantasy world need not be created across several decades–and yet if it isn’t, it will not measure up.

Authors and screenwriters don’t have to go away and devote the rest of their lives [to] creating a universe as large and self-sustaining as Tolkien’s, but against such a brilliant creation done such justice, all other attempts feel a little short-termist.

I assume “done such justice” refers to Jackson’s film, the implication being that the screenwriters need not necessarily invent an entire world but might find it ready-made in a literary work. The fact that the Harry Potter serial achieved such fierce fan devotion and high BO seems to confirm that. Though not an impressive stylist, J. K. Rowling shares with Tolkien a remarkable imagination when it comes to making the Wizarding World vivid to readers. She also anchors it just enough in the real world to make it appealing and easy to relate to. Her novels bear almost no resemblance to LOTR, apart from the fact that the Dementors seem derived from the Black Riders. To a considerable extent, the strongest aspects of the film adaptation’s version of Rowling’s world parallels that of LOTR, superb design and excellent casting being perhaps foremost among them.

Creating an original screenplay with a similarly original world, however, seems an extremely tall order. To be sure, it is not impossible. George Miller’s first Mad Max film was not a fantasy but an action-revenge film shot on the cheap with an unknown star-to-be. Its success, probably based on skillful direction and an appealing actor, allowed Miller to transform Max’s ordinary Australian Outback into a distinctive fantasy world, a post-apocalyptic Wasteland. This, too, was fairly low-budget, requiring little more than a desert, a bunch of eccentric, souped-up vehicles, and a team of daredevil stunt performers. Even greater success allowed the third film a big Thunderdome set, some modest special effects, and a second star. Most recently Miller gained a blockbuster-size budget for special-effects, an Oscar-winning co-star, and a multiplication of the weird vehicles. This is not to say that Miller’s created world is as complex as Middle-earth, but it has a visceral sense of reality and a distinctive look that set it apart from any other films, fantasy or not. But how often can you generate a Mad Mad-style franchise from almost nothing?

Alcock doesn’t mention it, but fairy tales have become a fallback option for Hollywood fantasy. Such films, adapting the originals into versions aimed at adults, have largely failed to catch on. (Given the recent failure of The Huntsman: Winter’s War, we might suspect that the success of Snow White and the Huntsman was due largely to the star power of Kristen Stewart, fresh off the Twilight series.) Fairy tales are sketchy stories with fantastical events and minimal characterization. They usually either take place more-or-less in our world or else spend little time describing the look of Faerie.The designers are left to their own imaginations to create settings, most of which tend to be pretty conventional.

Following in the footsteps of the LOTR and Harry Potter filmmakers, finding a novel or other literary property with the built-in popularity to carry a big-budget special-effects film seems the way to go. Despite the plethora of fantasy novels since LOTR appeared in the 1950s, choosing just the right one has proven a considerable challenge.

New Line’s adaptation of The Golden Compass, the first book in Philip Pullman’s brilliant His Dark Materials trilogy, was creditable but not exciting enough to create a successful film, let alone a franchise justifying the expense. Perhaps the novel was too little known in the US. The same could be true for The BFG, another British children’s classic, which is doing even worse at the box-office. (The studio could at least have had the sense to rename it The Big Friendly Giant, though that probably would not counteract what I suspect was the public’s mistaken impression that the film was aimed strictly at children, and very young ones at that.)

Alcock carries on his speculations.

So how does a different fantasy film emerge from the shade that Middle-earth put over all the competition? Frankly, it’d have to be another masterpiece to do it. The problem is the cohesion of vision or sincerity of intent from these other would-be franchises.

“Make a masterpiece” is excellent advice but rather difficult to follow. It doesn’t always work, either. Probably the two best mainstream American films I saw last year were Mad Max: Fury Road and Pixar’s Inside Out. Both were fantasies. Neither, as far as I know, drew any comparisons to LOTR from critics or fans, so they did escape its shadow. Both were highly praised by critics and won Oscars. They may or may not be considered masterpieces in the long run, but they certainly could count as such in the context of contemporary Hollywood. One made lots of money and may eventually spawn a sequel, given Pixar’s growing penchant for such things. The other, given its hefty budget, probably did not make a profit, or at any rate not one that Warner Bros. would consider large enough to justify taking the franchise to a fifth film–unless, perhaps, Miller went for a lower-budget project. So making a masterpiece may help distance a film from LOTR, but it does not guarantee a more practical sort of success.

On the issue of vision or sincerity mentioned above, Alcock touches on one subject that I think helps explain why it’s extremely hard to produce successful fantasies that have not the slightest whiff of Middle-earth about them. His point also explains why we seem to be stuck in a dismal summer where every week the same set of interchangeable films come out. He discusses Hollywood’s failure to follow up the LOTR with a fantasy franchise that would avoid the inevitable comparisons to LOTR.

Just think of The Golden Compass, New Line’s attempt to create a new fantasy franchise out of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, much more lukewarmly received and whose box office led to New Line’s end as an independent company. Now there’s food for thought–would Warner Brothers [sic], who own New Line as all but a label today, have really greenlit Lord of the Rings in its ultimate form?

I think we know that the answer to that question is almost certainly no.

In fact, LOTR actually did fail to get greenlit in its final form, though at a different major studio. As I describe in The Frodo Franchise, in 1998 Harvey Weinstein was planning to produce LOTR as a two-feature film directed by Jackson and with a budget of $140 million. When the project was a year and a half into the scripting and design process, Weinstein was called into Michael Eisner’s office at Disney, parent company of Miramax. Eisner demanded that he cut the film to one feature, made for $75 million. Jackson balked and persuaded Weinstein to put the project into turnaround for two weeks. Famously Jackson pitched it to Bob Shaye, founder and co-president of New Line, a man who knew the value of a franchise with a built-in fan base and proposed to make LOTR as three features.

Today’s New Line, a mere production unit of Warner Bros., could not undertake such a project on its own accord, and today’s Warner Bros. surely would not. With studios opting for the most established formulas, a film comparable in originality to LOTR being made, especially with all three parts shot simultaneously, would be little short of a miracle.

The only circumstance in which such things can happen would be an adaptation of a book so successful that it virtually guarantees box-office success. Warner Bros. undertook the Harry Potter series under such circumstances, given the overwhelming popularity of the book. That the resulting series of films pleased established fans and new audiences probably owes much to the fact that Rowling took an active role in consulting on the scripting and other aspects.

Today’s largely unappealing lineup of summer films (and I am writing here of mainstream Hollywood films, not including such original independent fare as James Schamus’ excellent Indignation) has been punctuated so far by two entertaining and satisfying items: The BFG and Pixar’s Finding Dorie. Both fantasies, one an undeserved box-office failure, the other a record-breaker. Which goes to show, I suppose, that good, non-LOTR-influenced fantasy (whatever its box-office record) rests with auteurs and Disney/Pixar.

Is television the answer?

Like numerous other writers, Alcock offers Game of Thrones as a model for what fantasy films with richly realized worlds might be.

If Middle-earth has a “successor,” it’s Game of Thrones. Based on George R. R. Martin’s books, the TV series has come far closer to Lord of the Rings‘ immersive world-building and cultural impact than any other fantasy, and perhaps suggests how Lord of the Rings might be adapted today.

He is far from the only writer to offer Martin’s books and the TV series based on them as an example of successful world-building. Many would say, to be sure, that the shadow of Tolkien’s and Jackson’s influence hovers over it, but perhaps that does not matter. It has brought respected long-form fantasy to TV, just as LOTR brought it to the big screen. It has gradually achieved critical acceptance, garnered a healthy number of awards, and contributed familiar tropes to modern culture, even for those unfamiliar with the books or series. I myself gave up on the novel after reading the first volume and have seen no episodes of the series. Already by the end of the first book it seemed to me that Martin was starting repeat his own devices, and if he was doing that within one book, what would later volumes be like? I certainly can’t see it as literature on a level even remotely approaching that of LOTR or even Harry Potter. I have not seen any episodes of the HBO series and hence cannot judge it. From what I can tell, it does not escape the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR, but that’s probably a matter of opinion.

Many fans who long to see an adaptation of Tolkien’s The Silmarillion have suggested that long-form television would be a more plausible medium than theatrical film. I consider The Silmarillion utterly unfilmable, except possibly in the hands of a brilliant animator, but that’s another issue. The point is that television, and especially powerful cable channels like HBO, are seen as the venue for long films that would be unlikely to be greenlit as high-budget theatrical features.

Despite appearances, I am not a keen fan of fantasy literature and films. The only fantasy novels (apart from children’s books) I have enjoyed enough to reread are LOTR, the Harry Potter series, and Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. The seven-part TV series based on the latter ended its American run on BBC 2 just over a year ago. I believe it is somewhat parallel to the LOTR film in being a reasonably successful–artistically at least–adaptation of a major work of literature It also bears no trace of Tolkien’s influence.

How does it escape? If you asked someone who had read both Martin’s books and Clarke’s whether they had read Tolkien, he or she would probably guess that Martin had and would have no idea whether or not Clarke had.

Martin admits his debt to Tolkien freely. “I revere Lord of the Rings, I reread it every few years, it had an enormous effect on me as a kid. In some sense, when I started this saga I was replying to Tolkien, but even more to his modern imitators.”

Clarke also was a Tolkien fan, but I have never seen anyone compare JS&MN to LOTR, either the original novel or the TV series. For one thing, she had other, quite different influences well, as described in a reader’s guide on her publisher’s website.

During an illness that required her to rest a great deal, Clarke re-read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and when she finished she decided to try writing a novel of magic and fantasy. She had long admired the fantasy writing of Ursula Le Guin and Alan Garner, but also loved the historical fiction of Rosemary Sutcliff and novels of Jane Austen. These various influences were to come together in a novel which is part magical fantasy, part scrupulously researched historical novel, with teasing faux-academic footnotes referencing a bibliography of magical books entirely of her own invention.

Clarke also has a literary skill that elevates her above most writers in the genre. Her approach was not to invent an imaginary world à la Middle-earth, but to begin by setting her story in the actual English history of the Regency era. Into that she inserted two magicians seeking to revive the tradition of Faerie-derived English magic and use it to aid their country during the wars with Napoleonic France. Her seamless blend of real historical figures and events with her own inventions can leave many nonspecialist readers wondering which is which.

I have already written about the TV adaptation of Clarke’s book, pointing out both what I consider some problems with the adaptation of the narrative and some real strengths of the series. As with LOTR, the adaptation’s strengths have much to do with the design, the special effects, and the acting. Indeed,the series won two BAFTA TV Craft awards, for production design (above, designer David Roger accepts his award) and special effects. In some ways, it could have been to TV what LOTR was to film, though it was far less successful with audiences and thus will no doubt have concomitantly less influence.

The elusive “masterpieces” of fantasy that Adcock suspects might escape from the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR could be either films or TV series. But unless the studios greenlight more imaginative fare, that shadow will persist for a long time.

On the point about whether Warner Bros. would greenlight a LOTR trio of films today. I discuss studio executives’ decisions about which fantasy films to make, specifically in relation to Warner Bros. and Jack the Giant Slayer, in “Jack and the Bean-counters.” In my 1999 book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood, I suggested that Hollywood’s originality and risk-taking had declined so much, even by then, that many classic and successful films could not be greenlit; I suggested Witness, Chinatown, The Fugitive, and Alien as fairly recent examples. By now the system has become even more exclusionary.

The idea that series TV offers the advantage of more time to play out the narrative of a long book is not true in all cases. Including credits, JS&MN runs a total of 406 minutes, while LOTR runs 558 minutes in its theatrical edition and an extra two hours in the extended home-video release. (In the 50th Anniversary edition, Tolkien’s novel runs 1029 pages without the appendices. The first edition of JS&MN is 782 pages.) Ironically, in the wake of LOT’s success, New Line optioned JS&MN as a possible successor to Jackson’s film. The Golden Compass took precedence, and eventually JS&MN became available for the BBC to adapt. Made as a trilogy, with a higher budget, it would have looked great on the big screen.

Wildstyle, Gandalf, and Batman in The Lego Movie (2014)

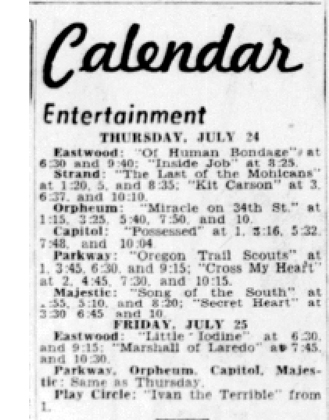

Born on the 23rd of July

The Wisconsin State Journal, Wednesday 23 July 1947.

DB here:

Today I turn 69. (Please keep the cheers discreet.) I was born in western New York State, but I’ve spent over forty years in Madison, Wisconsin. So for fun I thought I’d take a look at what you could have seen on 23 July 1947 in my current home town.

This isn’t (just) an exercise in baby-boomer self-regard. Looking at the movie ads in the Wisconsin State Journal for that fateful day can remind us of interesting stuff about American cinema of the postwar years. Or so I think, fueled by work on Hollywood in the 40s for a book I’m nearly done with.

Classics, just passing through

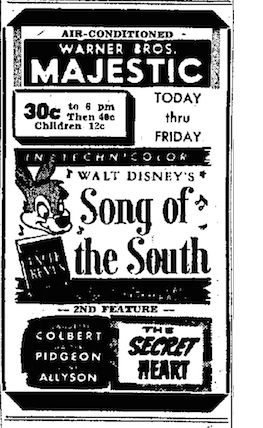

Song of the South (1946).

The first thing that strikes me the quality that’s on offer. On that Wednesday you could have seen four superb films (Rebecca, Stairway to Heaven, Song of the South, Possessed) and two worthwhile pictures (Of Human Bondage and Miracle on 34th Street). These movies are still remembered and admired.

Can this morning’s list of multiplex showtimes promise anything so enduring? Maybe Finding Dory and The BFG will be watched sixty-nine years from now, but our other current releases seem bound for oblivion. And of course the 1947 bill of fare was, with the important exception of Song of the South, designed for grownups.

Those who want to use this 1947 data-point as an example of the death of American cinema are welcome to do so.

Admittedly, today we don’t expect summer to generate the highest-quality films. (Though it often does; think of the last Mad Max installment. And James Schamus’s Indignation is coming up next week.) In 1947 the summer market was rather different from that today. Studios planned their major releases from late August onward, with big pictures playing through fall, winter, and early spring. June, July, and much of August were a slack stretch, when, Hollywood charmingly assumed, people wanted to be outside. So summer releases tended to be minor titles, and exhibitors turned to foreign fare, B pictures, and reissues.

Still, Possessed and Miracle were brand-new releases. At the end of the 40s, it seems clear, studios began releasing more of their important pictures in the summer. And as you can see, air conditioning–rare then, even in public buildings–lured some folks in.

In any case, for moviegoing purposes, I’d rather have been in Madison in July of 1947. In the two weeks sandwiching my birthday (16 July-30 July), I could have seen Brief Encounter, Her Sister’s Secret, Tomorrow Is Forever, Tender Comrade, The Sea Hawk, The Sea Wolf, Dead Reckoning, The Hucksters, The Unfaithful, The Lady in the Lake, Bohemian Girl, Boom Town, The Razor’s Edge, Love Laughs at Andy Hardy, Mr. District Attorney, Calcutta, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, Angel and the Badman, The Dark Mirror, Till the Clouds Roll By, Pursued, and Sister Kenny—along with a couple Lone Wolf and Falcon movies. Not a bad lineup. And I’m not counting La Grande Illusion and Ivan the Terrible on the UW campus.

Safety in numbers

Possessed (1947).

Then there’s quantity. Madison, Wisconsin had a population of about 65,000 in the year of my birth. It was dwarfed by Milwaukee, which had nearly ten times that. Yet by my count, over the two weeks around my birthday, a Madison moviegoer had 73 films to choose from. For the same 15-day stretch in town today, I come up with no more than 20. (For both time frames, I’m not counting campus or library screenings.)

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

My biggest choice today involves where, when, and how to watch. The Secret Life of Pets is playing on nine screens, and I can see it in 3D or flat versions. I can see it at 8 AM or 8:20 or 8:35, and so on to 11:30 PM. The showtimes are user-friendly. By contrast, Madison movies in 1947 were appointment viewing, and most titles played only two or three times a day. While you could just drop in at any point, the newspaper did publish show times, so you could plan to watch the movie straight through if you wanted.

Of course my 69-year-old self has a much bigger choice of movies than what’s in theatres. I can choose among thousands of titles on cable TV, disc, or streaming. TV wasn’t a significant part of the American landscape in 1947. Cinema existed in an economy of scarcity rather than overabundance.

This circumstance led people to go immediately to see the newest picture, as they couldn’t be sure it would return in second-run or a reissue. Today many of us skip a new release in theatres because we know we can catch it in a later video window. Does this all-you-can-eat plenitude make cinema seem less urgent and immediate—more a matter of “content” filling libraries and bookshelves and hard drives and Netflix queues? I think so. We’re all collectors now, in a way a 1947 moviegoer couldn’t be, but that means we lack the impulsion to see most films immediately. It takes effort to go out to see a film, but maybe that effort makes the experience more valuable (when the movie is satisfying, of course).

Dueling duals

Oregon Trail Scouts (1947).

The ads reveal more about quantity. You’ll have noticed that a great many of the films are playing on double bills (“duals”). From the 1930s on there was a perpetual debate about whether duals helped or hurt the industry. Most studio chiefs deplored them and confidently announced that a majority of audiences didn’t like them. The trade papers regularly ran stories predicting that the dual’s days were numbered.

They were wrong. Duals persisted into my college years; to see Help! (1965) twice in first release without buying another ticket, I had to sit through The Glory Guys (1965). Most exhibitors were independent of the studios, and they liked duals. So, obviously, did many viewers, who enjoyed getting two movies for the price of one.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

Several industrial factors are connected here. The two Madison theatres running single features were the main picture palaces. The Capitol and the Orpheum each had about 2200 seats. They were the prime first-run houses, affiliated with two studios: the Warners chain controlled the Capitol, and Twentieth Century-Fox controlled the Orpheum. No surprise then that the former ran Possessed (a Warners picture) and the Orpheum ran Miracle on 34th Street (a Fox release). So these houses could run the premiere engagement of each film, counting on the freshness of the release to attract customers. These venues screened their first-run single features for a full week.

The other theatres in the ad are running duals. Some of them ran recent releases, but late in the run. For instance, the Parkway (despite its name, another downtown theatre) was a big venue, with a 1200-seat capacity. On my birthday it screened Cross My Heart (a January ’47 release) and Oregon Trail Scouts (a May release). These were first-run, but with less must-see appeal than Miracle and Possessed. Also, Oregon Trail Scouts is a prototypical B picture, running 58 minutes. So the Parkway, another Fox-controlled screen, mated a mildly attractive Paramount programmer or “nervous A” with a Republic B. A third Fox venue, the Strand, a 1300-seater on the square, drew on second-run titles and reissues for its duals.

The town’s smaller theatres relied on duals. The Majestic, an old vaudeville house with some of the most skewed sightlines in Christendom, was at that point another Warners house. Yet it had no qualms about showing subsequent-run titles from Disney/RKO (Song of the South, in its third Madison run) and MGM (The Secret Heart, back for a second).

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

The Madison was yet another Fox house; on my birthday it was showing two Universal releases: Stairway to Heaven (the US title of A Matter of Life and Death), paired with the unlikely partner The Vigilante Returns, a B. Both were first-run in Madison.

As a result, in my one-day snapshot every major Hollywood studio is represented; even RKO gets in with its “Passport to Nowhere” short. How can this be, in a town with four Fox screens, two Warners screens, and only one independent exhibitor? Research by our colleague Andrea Comiskey has shown a remarkable flexibility in studio screening policies. Often a subsequent-run house owned by a studio played few or none of the studio’s own releases. This way everybody could make money off everybody else’s movies. Such are the ways of oligopolies.

Why so many B’s, particularly Westerns? Given double bills, they were what the trade papers openly called fodder, and they saved money. B’s were rented on a flat-fee basis, while A’s were rented on a percentage basis. Some exhibitors ran the B more frequently than the A each day, so as to keep more of the box-office take. Such wasn’t the case with the Madison, though: Both Stairway and Vigilante played an equal number of times each day.

Was the B the chaser, clearing the house after the A? Maybe, but maybe someone coming to see a prestigious Powell and Pressburger would stick around for Jon Hall and Andy Devine. In any case, since the Big Five studios were making fewer pictures in the 1940s and were concentrating on A items (the big-ticket income), the ongoing demand for duals helped less important studios, which were heavy suppliers of B’s.

There was only one independent house in Madison proper. The Eastwood (still standing, now a live venue and called the Barrymore) was playing second-runs in its 950-seat auditorium.

Finally, runs were tied to ticket price. I haven’t got good information on ticket costs in these theatres, but the fact that the Majestic boasts of charging $.30 until 6 PM, and then bumps the cost to $.40, is typical of a second-run house of the time. First-run tickets, depending on time of day, could be $.50 or more.

Those costs, by the way, translate to ticket prices between $3.30 and $5.50 in today’s currency. Another data point favoring the good old days.

Heavy rotation

The Middleton Theatre, Middleton Wisconsin, in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

Duals multiplied the number of pictures on offer. So did the length, or rather the brevity, of runs.

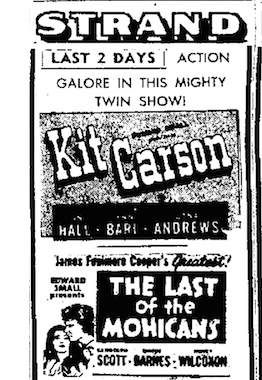

The first-run A’s, Possessed and Miracle on 34th Street, ran a week; Miracle, in fact, was moved over to the Madison at the end of July for a longer stay. But most duals changed more frequently. The Madison’s dual of Tomorrow Is Forever and Tender Comrade ran five days, as did the Strand’s Last of the Mohicans and Kit Carson. But the Parkway typically changed bills every three days, while other theatres split up the week even more. Some programs ran only two days.

We’re so used to pictures hanging on for weeks or months that these rapid playoffs are surprising. But here my birthday snapshot is a bit misleading. Many of the films brought in for two or three days were second-run titles, and a surprising number were reissues.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

Eric Hoyt, another Madison colleague, points out in his splendid book Hollywood Vault that the Forties was a great era of reissues. Re-releasing 1930s classics like King Kong and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved that an older picture might make as much or more than a new one. In any case, reissues could be cheaper for theatres to rent, especially in the slower summer months, and they could be turned over quickly.

The number of reissues increased powerfully just before my birthday. In late May, the Hollywood Reporter claimed that of 224 pictures playing in metropolitan New York, 105 were “oldies.” Just after said birthday, HR reported that “the highly satisfactory boxoffice results from reissues in recent months, plus the necessity of averaging down the cost of new productions which continue to call for multi-million dollar budgets, will result in nearly twice as many reissues in 1947-48 as in the past year.” That number was said to be 75 from the Majors, along with another 100 or so titles already sold or leased by non-Majors.

The oldest reissue on offer in Mad City on my birthday was The Last of the Mohicans (1936), paired with Kit Carson (1940). This package had already had great success in New York and had helped sustain the reissue boom. So strong was this Mighty Twin Show that producer Edward S. Small could demand not the usual flat-rate terms but rather a 35% of the box office. In Madison during the weeks around 23 July, you could have seen a great many other films from the 1930s and 1940s, on brief-stay duals.

Speaking of reissues, the Middleton, the venue announcing Rebecca in the ad, is interesting in its own right. Middleton is a pretty bedroom community west of Madison, then with about 2000 souls. Now, thanks to infill, it’s more or less a continuation of our town. Its theatre, an independent house built in 1946 and with a capacity of 500, ran both second-run and reissues, including, during the DB magic weeks, Sun Valley Serenade (1941), The Westerner (1940), and, for one day, Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942).

Maybe more interesting is that the Middleton was a Quonset hut, with a wraparound roof.

More about the Middleton here. Kristin and I saw E. T. there, and I wish we’d gone more often. It was demolished in 1992.

Foreign accents

A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven, 1946).

The presence of Stairway to Heaven (in first run) points up another trend. During the 1940s, foreign films gained a new prominence on American screens. While reissues were flooding New York City screens as noted, the number of imports among them was sharply up: fourteen British titles, five French, four Spanish, three Italian, two Russian, and one Swedish.

Those proportions reflect the growing popularity of British cinema. At year’s end, Variety noted that the number of British releases in 1947 doubled from the previous year, from ten to twenty. In the two weeks surrounding my birthday, Madisonians could have seen Brief Encounter, also at the Madison. The Madison seems to have sometimes operated as an art house. It screened Open City a month earlier, promoted in a memorable ad that somehow plays up sexytime without showing Anna Magnani.

Note what’s playing with it. The Madison stayed classy.

1946 was the high-water mark of American movie attendance and Hollywood studio profits. 4.7 billion US tickets were sold, and profits came to nearly $120 million. Attendance remained strong in 1947, but profits started to fall steeply, to about $87 million. The soaring costs of production, including millions spent on rights to projects that were never filmed, came due. And soon enough attendance dropped calamitously as well. Ticket sales in 1952 were only a bit more than half of 1946’s total. A great many Americans stopped going to the movies.

There were rumblings, though, before I showed up. “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” announced the headline of Hollywood Reporter for 20 May 1947. Was this just a “spring slump,” such as those before World War II, when good weather drove people outside? “If there is no general rise in grosses by the middle of July,” said one executive, “then our fears will have been realized, as it will reflect an economic crisis.” Studio employment was off 20%; the Majors’ building plans were put on hold; and reissues from non-Major sources were gaining a bigger share of the receipts. Ultimately, 1947 fell off only a little, but film folk were nervous. The big dip would come soon.

Another crisis: In less than a year after my birthday the Supreme Court would declare that the studios’ ownership of theatres was monopolistic, and the companies would begin gradually splitting off their theatre chains.

I was born, then, on a sort of cusp. By the time I was 5, people were declaring the studio system dead. Knowing nothing of this, I continued watching new releases (Peter Pan, Francis the Talking Mule movies) and old films that were starting to show up on TV. I didn’t suspect that, decades along, I would spend my more-or-less adult life studying those movies that played the Capitol, the Parkway, and the Middleton. Just looking at this page from the State Journal has me hoping that Kristin gets me a time machine for my next birthday.

For help in preparing this entry, thanks to Lea Jacobs, Jeff Smith, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Lisa Marine, and Rob Thomas.

Some sources: “Double-Bill Reissue Packages Prove Surprising B.O. on B’way,” Variety (9 April 1947), 7, 18; “Re-Issues Flood New York Screens,” Hollywood Reporter (22 May 1947), 1, 3; “Reissues Doubled for 1947-48,” HR (26 August 1947), 1, 11;”Industry Schedules 130 Re-Releases for This Year,” HR (5 February 1948), 1, 13; “Boxoffice of Nation on Skids,” HR (20 May 1947), 1, 12; “Industry in Crucial Period before Upturn, Say Toppers,” HR (26 May 1947), 1, 12; “July Will Disclose Actual Extent of Boxoffice Downturn,” HR (9 June 1947), 10; “8 Majors and 4 Lesser Distribs Released 428 in ’47 vs. 405 in ’46,” Variety (31 December 1947), 6. Chapter 6 of Susan Ohmer’s book George Gallup in Hollywood (Columbia University Press, 2006) provides an excellent overview of the disputes about double bills.

There was another crisis in my late prenatal phase. In response to shopkeepers, the ever-watchful Wisconsin state legislature had drafted a bill banning candy, food, and drink from being sold in movie houses. Exhibitors mobilized and lobbied for tasty snack treats. “With boxoffice grosses rapidly slipping from their wartime peaks to pre-war levels, the candy, popcorn, sandwich and soft drink sales now are especially essential to keep the houses on the profit side of the ledger.” “Wisconsin Candy Sale Ban Doomed,” HR (7 May 1947), 5. Fortunately for all Cheeseheads, this bill was defeated.

Browsing the wonderful site Cinema Treasures can make you aware of all those lost movie houses. The Wisconsin Historical Society presents many photos of Madison’s old theatres. My photo of the Middleton in the 70s comes from this collection, Reference no. 5572.

The saga of Madison’s Orpheum is told in part here, though an update on all the intrigue is probably in order. At least the magnificent sign has been redone and has gone up. The Capital Times covers the process here and here. The refurbished sign got lit up last night. For more on local theatres, including the ones I actually frequented back East, go here and here. Also relevant is this visit to Rochester’s Cinema Theatre, with information from Andrea Comiskey. Also a cat.

On the importing of movies from overseas at this period, the definitive source is Tino Balio’s book The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2010).

P.S. 30 July 2016: The Middleton Theatre stirs fond memories. See Nadine Goff’s Facebook page on historic Wisconsin photographs for reminiscences of sticky floors and rain on the roof.

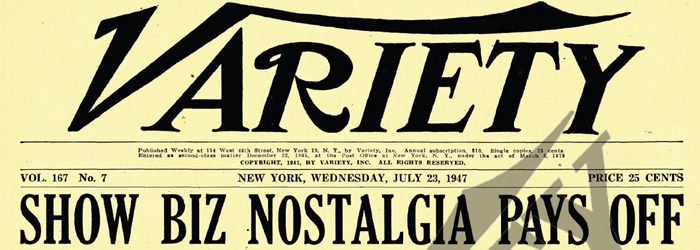

Another fateful birthday headline.

Hail, again, to the King

A Touch of Zen (1970).

DB here:

Criterion has just put out its DVD/Blu-ray of King Hu’s A Touch of Zen. I wrote liner notes for it, which are available on the Criterion site. I haven’t gotten my copy of the edition yet, but the reviews I’ve seen are praising Tony Rayns’ interview (no surprise) and the other features.

For more on one of my favorite cuts in A Touch of Zen, you can visit this blog entry (complete with splice marks). There’s also a discussion of the goldenrod combat here. In Poetics of Cinema, there’s a longer essay called “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” and a chapter of Planet Hong Kong is devoted to comparing his work to Chang Cheh’s and Lau Kar-leung’s.

With A Brighter Summer Day, this is another Criterion triumph and a must for every cinephile. And why am I never around when a swordswoman flies by?

Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly

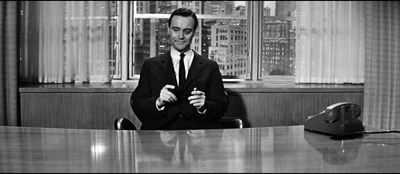

The Apartment (1960).

DB here:

Rory Kelly, whom I met some years ago at a conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, has been a pioneer in linking the practices of film production to larger issues of narrative, performance, and artistic form. What follows is a version of a superb paper he gave at the Society’s annual meeting in Ithaca in June. Since Kristin and I are always eager to know how practitioners think of their craft, we jumped at the chance to pass along his thoughts in one of our guest blog entries.

Rory comes fully prepared to the task. Currently an Assistant Professor in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, he has been a bright light in filmmaking for many years. His first feature, Sleep with Me (1994) premiered as an Official Selection at Cannes and was released by MGM/UA. His second feature, Some Girl (1998), garnered him the DGA-sponsored Best Director Award at the Los Angeles Film Festival, and his 2006 short, The Women, premiered at the Long Island Film Festival. He was also co-executive producer of mtvU’s Sucks Less with Kevin Smith. Rory has been a Film Independent Screenwriting Fellow and is currently working on several research projects, including studies of discourse analysis and emotional expression in film. At the same time, thanks to a 2016-2017 Heillman Fellowship, he is preparing a feature documentary about racism in America, To Someday Understand.

Here’s Rory on a perennial problem of the screenwriter: the character arc.

Since the 1960s, the character arc has become all but obligatory in Hollywood movies. Genres like sci-fi and horror, once largely unconcerned with character change, now often include it. Compare, for example, the 1953 version of War of the Worlds with Steven Spielberg’s 2005 remake. In the latter the alien invaders are not only defeated, but in the process Tom Cruise’s character, Ray Ferrier, becomes a better father.

Why has character change become so prominent? In The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006), David offered some suggestions. The psychological probing in plays by Arthur Miller, Paddy Chayefsky, and Tennessee Williams became popular models of serious drama. Teachers and writers were persuaded by Lajos Egri’s book, The Art of Dramatic Writing (1946), in which the author advises that characters should grow over the course of a play. There was also the impact of self-actualization movements of the 1960s and 1970s that held out the promise of personal growth and transformation.

It’s also likely that star power has had considerable influence. When trying to raise financing for a low-budget indie script a few years back, my collaborator and I were advised by three different seasoned producers to give our protagonist a more pronounced arc or we would never be able to attract a name actress to the role. Whether they were right or not, I do not know, but their shared assumption about attracting talent is telling.

Given how common the character arc has become, we need to better understand how it is typically handled. I think we can identify and analyze six narrative strategies that create a particular character type: the protagonist who is flawed but is capable of positive psychological change. My primary example will be The Apartment (1960).

I’ll also consider aspects of character change in Casablanca (1942), Jaws (1975), and About a Boy (2002). This list will allow me to consider the character arc over six decades, from the studio era to contemporary Hollywood, and across several genres. Limited as it is, this set of films suggests that certain techniques of character change recur again and again. In tracing them, I’ll occasionally make reference to the four-part plot pattern Kristin has set out in Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) and several entries on this site: the Setup, the Complicating Action, the Development, and the Climax.

A six-step program

Casablanca (1942).

First, a filmmaker seeking to construct a character arc will almost inevitably begin by establishing that his or her protagonist is of (1) Two Minds. I mean by this that the character has competing impulses. Think of Rick in Casablanca. On the one hand he is inclined towards communal action; on the other hand he sticks his neck out for no one. This latter behavior is solidified during the Setup portion when he assists in Ugarte’s arrest.

It can be termed Rick’s (2) Negative Behavior Pattern. It is a pattern because it is a type of behavior Rick enacts again and again, as when he repeatedly refuses to give the letters of transit to Victor and Ilsa. The film even turns Rick’s selfishness into a motif.

Still, Rick retains an impulse towards virtuous behavior, his (3) Positive Behavior Pattern. During the Setup, for example, he does not allow a notorious Nazi to gamble in his café. Later he helps a destitute young couple earn passage to America by allowing them to win at roulette.

The film as well makes a motif of Rick’s virtuous side.

The ongoing interaction of these two behavior patterns allows the filmmakers to maintain audience sympathy for Rick, to motivate his final change of heart—if Rick were not of two minds, his final transformation would come out of nowhere—and to delay that change of heart long enough to create expectations and suspense.

What often postpones a protagonist’s change of heart is a (4) False Belief. In many films a misunderstanding is introduced that motivates the protagonist’s negative behavior pattern. Because of this the character need only discover the truth in order to be reborn. Think again of Rick. It is because he falsely believes that Ilsa once jilted him, leaving him alone in the rain at a train station in Paris, that he has become a sullen saloonkeeper who sticks his neck out for no one.

But once Rick learns the truth—that Ilsa left him because she discovered her husband was alive—Rick forgives her. He then devises a scheme to help her and Victor escape, and he makes plans to join the Resistance. The truth, in short, sets Rick free and quickly and efficiently allows for his change of heart.

Another way to look at Rick’s transformation is that his false belief about Ilsa has made him essentially a nihilist who believes that there is nothing worth living for. When Victor says, “If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die,” Rick replies, “What of it? Then it’ll be out of its misery.” Seen from this angle, when Ilsa finally convinces Rick of the truth, we are meant to infer that his change of heart is the result of a realization that love and loyalty still exist in the world.

The final two strategies I want to discuss concern the story world. In the case of flawed protagonists the rules and values of the fictional world may be established as conflicted in a way that matches the protagonist’s competing impulses. On the one hand there is what I term the (5) Normal World. This constitutes the dominant rules and values in play as the movie begins. Against this there is what I term the (6) Possible World. This constitutes what the normal world should be.

Think once more of Casablanca. That city is established as a place where a great many people have abandoned their better impulses and are out only for themselves. The primary representative of this worldview is the charming but corrupt Captain Renault. However, the story world also includes Victor and other members of the Resistance, and they are believers in a new world; one based upon a common cause. So the story world is, like Rick, flawed but of two minds.

Rick occupies a psychological space between Renault and Victor. In the end, by siding with Victor, Rick not only abandons his negative behavior pattern, he also begins the process of overturning the rules of the normal world. The change is suggested by Renault’s becoming, as it were, Rick’s first convert. They leave together to join up with a mysterious free French garrison at Brazzaville.

Rick’s character arc is not an isolated device but a central organizing principle of the plot. The same process is at work in The Apartment.

The Apartment: A normal world?

The Apartment tells the story of an ordinary accountant, C. C. Baxter, played by Jack Lemmon. In a calculated attempt to gain a promotion, Baxter allows his bosses to use his apartment for their extramarital affairs. Baxter is also smitten with an “elevator girl,” Fran Kubelik, played by Shirley MacLaine. But unbeknownst to Baxter, at least during the first half of the film, Fran is having an affair with the big boss, Mr. Sheldrake, played by Fred McMurray. Sheldrake is only stringing Fran along, though, and because of his treatment of her she eventually attempts suicide. Baxter finds her just in time and with the help of his neighbor, Dr. Dreyfuss, saves Fran’s life.

Baxter becomes Fran’s caregiver, but also Mr. Sheldrake’s protector, ensuring that news of Fran’s suicide attempt does not leak out. In the end, however, Baxter learns the error of his ways and finally follows the advice he is given by Dr. Dreyfuss.

When Baxter does become a mensch, he succeeds in winning Fran’s heart.

The six-step strategy displayed in Casablanca is launched in the opening few minutes of The Apartment.

We learn a great deal from this opening sequence. We learn that Baxter has a problem with his apartment and we learn that Mr. Kirkeby, the boss using his apartment, doesn’t respect him. The boss’s disdain helps garner sympathy for Baxter. Yes, Baxter is ill-advisedly allowing his bosses to use his apartment, but his bosses take advantage of the situation and mistreat him.

So why does Baxter let his bosses push him around? He wants a promotion, but why must he be so obsequious to get it? Is he unworthy? No. As we see right away, he is a hard worker.

In the opening voiceover we learn that Baxter is smart, or at least good with numbers, that he is enthusiastic about his work as an accountant, and that he respects and is impressed with the company he works for. He is a diligent company man, both capable and earnest. So why is he such a pushover?

To answer that question we need to look at the normal world. The film almost immediately introduces us to Consolidated Life, the insurance company Baxter works for. It is a beehive, an impersonal and monotonous corporate colony. And Baxter is depicted as an anonymous drone: he works on the 19th floor, Section W, at desk #861.

Baxter is not just a cog in a machine; he also behaves like a machine when we see his head bob up and down in unison with his calculator. If at the end of the film Baxter becomes a mensch, a human being, then at the beginning of the film he is an automaton. He does what he is told. That is part of being a company man.

Fran, who functions as co-protagonist, works inside a machine. Her gray uniform blends into her surroundings.

Fran and Baxter are insignificant, powerless and anonymous people lost among the 8,042,783 New Yorkers. In The Apartment status, power, money and the freedom to do what you want, other people be damned, are the highest values people can aspire to. And those without status, power and money are nobodies. That is how the normal world works in The Apartment.

The only way to escape anonymity and insignificance is to climb the ladder of corporate and/or social success, and presumably become one of the exploiters. This is exactly what Baxter and Fran try to do. Baxter, after all, wants to be a big boss like the men he lets use his apartment. His gamesmanship eventually allows him to jump the promotion line. His co-worker has been at Consolidated Life twice as long as Baxter, but because he does not play the game, he is not promoted.

Fran wants a promotion too: from mistress to wife of a very powerful man. She becomes to some degree complicit with Sheldrake in disregarding the needs of his wife.

Both Baxter and Fran, then, are willing to climb over other people to get what they want. Still, they aren’t vicious. In most ways, Fran is a kind and encouraging person. When Baxter comes up for his first promotion she tells him, “It couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.” And Fran actually loves Sheldrake. Fran is not Sylvia, a woman we meet in the opening sequence, who seems mostly interested in having a good time.

Just as Fran is not like Sylvia, Baxter is not like his bosses. For one thing, he apologizes to his neighbors for all the noise his bosses make during their trysts. He even tries to correct the situation. And unlike Sheldrake and Kirkeby, Baxter does not want to simply seduce Fran.

Baxter is naïve, a romantic, a rank sentimentalist. And his chances for success in this world, like Fran’s, are limited.

In sum, Baxter and Fran are of two minds. They exhibit both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern. This is very important. Because they both basically have good intentions—or aren’t cynical enough for the world they inhabit—they can grow as characters.

But given their good intentions, why do Fran and Baxter have negative behavior patterns? The answer is that each harbors a false belief (related to the normal world) that motivates their negative behavior pattern. Fran’s false belief is that Sheldrake loves her. And because of this she continually trusts him. Here she is going off in a cab to sleep with him, even though we know that Sheldrake hardly cares about her.

In parallel fashion, Baxter believes that corporate success will bring him happiness, but in the end it doesn’t. He gets his big fat promotion with his own office, and he’s miserable.

Still, as long as Baxter harbors the illusion that climbing the corporate ladder will make him happy, he is willing to kiss up to his bosses and allow them to push him around as a way to get ahead. That is Baxter’s negative behavior pattern: he is a toady.

The Apartment: Delay and the darkest moment

Sustaining a character’s positive and negative behavior patterns often becomes of central importance in a film’s second half, when what Kristin calls the Development is launched. In some films the protagonist actually has enough information by this point to reconsider the false belief, but that doesn’t happen. The protagonist clings to error.

The midpoint of The Apartment is the moment roughly an hour into the film when Baxter discovers Fran comatose in his bed. As Kristin points out, a midpoint typically recasts character goals, and Baxter gains a new purpose: saving Fran.

Baxter is worried that Fran will try again to kill herself, so a lot of the Development focuses on his attempts to keep her safe. But Baxter is also protecting Sheldrake during this section of the film. He induces the doctor not to report Fran’s suicide attempt to the police, and he hides Fran in his apartment until she’s better. Baxter’s competing motives, in other words, remain in play. Helping to save Fran’s life, and learning that there is a terrible cost to Sheldrake’s callous behavior should be enough to motivate Baxter to turn against Sheldrake. But he remains on the job.

We see something similar happen about twenty minutes into the Development, when Baxter phones Sheldrake to tell him about the suicide attempt. Sheldrake won’t even come to visit Fran. Baxter is confused and disappointed by this response, but he nonetheless promises his continued support.

This is a common strategy during a Development section. The flawed protagonist is one or more times brought to the brink of character change, but he or she pulls back, clinging to the negative behavior pattern. We see exactly this withdrawal in Casablanca. At the midpoint in that film Ilsa visits Rick and tries to tell him about her relationship with Victor. Rick has an opportunity here to accept the truth, which would set him free, but he rejects it. He clings to his false belief that Ilsa betrayed him and Paris.

Rick is given a second chance roughly halfway through the development when he allows the young couple to win at roulette. Rick’s employee, Karl, is watching from the sidelines, and he is thrilled. He believes that Rick is turning over a new leaf, and so do we. But immediately following this event Victor directly asks Rick for the letters of transit, and Rick bitterly says no.

These are of course delaying tactics, and ones we should expect. Kristin points out that the Development section usually contains numerous delays that create rising tension and suspense, while forestalling resolution.

In The Apartment‘s Development section, certainly Fran’s change of heart is delayed. Despite being driven to attempt suicide by Sheldrake’s treatment of her, she nonetheless announces the next day that she’s still in love with him. She even reaffirms her false belief.

Fran’s near-death experience should be enough to convince her that she needs to end her relationship with Sheldrake, but she too clings to her false belief and negative behavior pattern. Still, in spite of all this, it would be a mistake to say that no progress is being made. Baxter after all is horrified by what Fran has done to herself and Fran is beginning to entertain doubts. She says that “maybe” Sheldrake loves her. And all of this culminates in a moment of self-knowledge:

They are, in short, changing. Also, the possibility of a romantic relationship is finally introduced when Baxter and Fran prepare to sit down to a candlelit dinner together.

With these new story premises in place, the stage is set for Baxter and Fran’s final changes of heart in the climax. But not before a few more delaying tactics are deployed.

First, Fran’s brother-in-law Karl arrives and breaks up Fran and Baxter’s dinner plans. Then Baxter visits Sheldrake to tell him that he is in love with Fran and intends to marry her. But Sheldrake beats him to the punch. His wife has found out about his philandering and kicked him out of the house. Now Sheldrake plans to marry Fran. But to thank Baxter for taking care of business, Sheldrake gives him his big promotion.

As we’ve seen, corporate success is no longer what Baxter wants. In current screenwriter parlance, this is his darkest moment. It’s immediately followed by this exchange:

Fran is clearly ambivalent about her impending marriage to Sheldrake, and Baxter is clearly acting out, trying to hurt Fran. Also, Fran is deeply disturbed to see the cynical side of Baxter out in full force. And this brings me finally to the possible world. As we also saw in Casablanca, the story world in The Apartment is divided, and again the question is who will the protagonist become. Will Baxter grow up to be Dr. Dreyfuss, who represents a communal worldview, or will he grow up to be Mr. Sheldrake, who represents a selfish worldview?

Now it seems that Baxter has become Sheldrake–except we don’t, or aren’t supposed to, believe him. The real point of the exchange between Baxter and Fran is that Baxter no longer holds his false belief. He is using it now only as a defense mechanism, as a cudgel to punish the woman he sees as having betrayed him. He is, in short, pretending. And since he is no longer committed to his false belief he can change.

As has become typical in Hollywood films, the protagonist’s darkest moment leads to enlightenment. In the very next scene Sheldrake asks Baxter for the key to his apartment so that he can bring Fran there for New Year’s Eve, and Baxter says no. When Sheldrake threatens to fire him, Baxter angrily throws a key onto Sheldrake’s desk, and the quiet confrontation ensues.

Baxter thought that the way the stand out was to play along, but in the end he discovers that the way to stand out is to stand alone and cease to be a collaborator. Also, Baxter’s transformation, like Rick’s in Casablanca, inspires a conversion in another character, Fran, and in this way it suggests an overturning of the rules of the normal world. As we’ve already seen, Fran is ambivalent about her new relationship with Sheldrake. And when Sheldrake at a New Year’s Eve party tells Fran that Baxter quit and wouldn’t give him the key, she smiles mysteriously as if finally seeing the light.

She realizes it is Baxter who loves her and not Sheldrake. So she abandons her false belief and the negative behavior pattern it engenders. She leaves Sheldrake and rushes to meet Baxter. And that’s the end of the story.

Two men of two minds

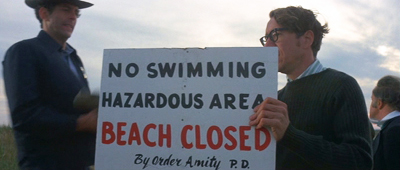

Finally, how enduring are these character-arc patterns? Consider, briefly, Jaws and About a Boy.

Chief Brody is a former New York City police office who has become sheriff of a small island community, Amity. Why did he leave the city? Because, as he explains, crime in New York is out of control and he couldn’t do anything to change that. So he has come to Amity, a world in which, he thinks, one person can make a difference.

Yet for this cop, living in Amity is a cop-out. There hasn’t been a murder there for thirty years. It is a town where one person doesn’t have to make a difference. Yet when the shark arrives, Brody discovers that Amity is the same as New York City. He wants to close the beaches, but the city officials won’t let him. He crumbles under their pressure. Brody is as powerless to make a difference in Amity as he was in New York.

That is how the normal world works in Jaws, and Brody, like Baxter, initially conforms to it. At the beginning of his story he’s defeatist. He always backs down in the face of conflict. He is not confident. Later, on Quint’s boat he wants to turn back. He’s always feeling overwhelmed, a state expressed in his fear of drowning. So Brody goes along to get along.

Accepting his powerlessness is Brody’s negative behavior pattern. But like Baxter and Rick, he can’t help caring. He works to close the beaches, if only for a day, and after a young boy gets killed, he accepts the blame.

Brody exhibits the typical split between positive and negative behavior. Yet because he’s of two minds, he can change. In a crucial turning point, he vows to join Quint and Hooper in hunting the shark. At the climax, he doesn’t back down. He is fearless and he does make a difference. He helps save the town, and in the process he gets over his fear of drowning.

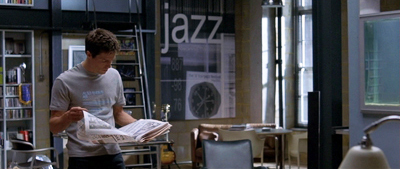

About a Boy, a British-American-French coproduction, released domestically by Universal Pictures, suggests that the techniques I’ve been considering have some cross-border appeal. A 38-year old man-boy, Will Freeman, played by Hugh Grant, lives in luxurious isolation off the royalties from a popular Christmas song his father composed decades before.

Neatly reversing John Donne’s dictum, Will asserts in the opening moments that “all men are islands.” In accordance with this philosophy he has built for himself “a little island paradise,” a swanky apartment filled with cool consumer goods like a chrome-plated espresso maker, a sleek TV, and a vast CD collection. But then Will meets and ultimately befriends Marcus (Nicholas Hoult), a 12-year old misfit with a suicidal mother, who lives his own willed exile because of not being accepted at school.

The story deals with how Will and Marcus and Marcus’s mother Fiona (Toni Collette) become integrated into the world.

Will and Marcus are co-protagonists, but Will’s character arc is more pronounced. Will’s false belief, of course, is that he can make it alone. The problem, though, is that solitude leaves his life devoid of meaning. He has no job and he sleeps with many women but doesn’t date any of them, at least not for very long. As he several times states, “I don’t do anything,” or more to the point, “I do nothing.” Will, however, sees this lack of meaning as a positive: “Me? I didn’t mean anything, about anything, to anyone, and I knew that that guaranteed me a long, depression-free life.”

Will’s false belief is not simply that he thinks he can make it on his own; he believes he can avoid misery by avoiding commitments. This is most apparent when Marcus’s mother attempts suicide.

While Will helps out by driving Marcus to the hospital, the sequence ends with a grim bit of voiceover as we see Will drive off alone into the night.

The thing is, a person’s life is like a TV show. I was the star of the Will show, and the Will show wasn’t an ensemble drama. Guests came and went, but I was the regular. It came down to me and me alone. If Marcus’s mom couldn’t manage her own show, if her ratings were falling, it was sad, but that was her problem.

Will, however, is of two minds, a state the film expresses in a number ways. First, despite being a committed loner, he very early in the plot begins dating a single mother. As we see him gleefully playing with this woman’s young son, he says in voiceover: “And for the next few weeks I was suddenly Will the good guy.”

When Will decides to break up with this woman, in part because she made him late to an IMAX movie, he adds, “I was going to have to end it, but having been Will the good guy I did not relish going back to my usual role of Will the unreliable, emotionally stunted asshole.” He is, apparently, self-aware, and his use of the word “role” seems intentional, suggesting as it does that Will the Asshole is a persona he adopts to avoid complications. We also learn that in the past Will volunteered at a soup kitchen, though he admits he never made it there to help out. And we discover that for a time he worked the phones at Amnesty International, but seems to have mostly used this as an opportunity to pick up women on his call lists.

The point the filmmakers are comically making is that Will has good impulses, but is unable to sustain them in the long term. He has both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern, the latter very clearly motivated by his false belief.

The normal world is established as one in which people are abandoned. The film is full of single moms, including Marcus’s mother, and Will tries to abandon everyone he meets. In the opening scene he throws away the phone number of a woman he has slept with, even as she is leaving an inviting message on his answering machine.

Most significantly, Fiona almost abandons Marcus when she attempts suicide. In the wake of this, Marcus is worried that his mother will try again, and that she may succeed when he’s not there. He gets an idea: “Suddenly I realized that two weren’t enough. You needed backup.” With this realization Marcus defines the possible world for us. It is one that is comprised of teamwork and mutual support. In search of this new world, Marcus attempts to fix up Will with his mother. His goal is to get Will to marry her so that they can both look after her.

The dreamed-of marriage never occurs, but Marcus and Will slowly become friends, spending most afternoons together watching TV and sometimes talking. Will helps Marcus become more cool, which allows him to begin making friends at school.

Because of his growing friendship with Marcus, Will comes to realize that misery stems from loneliness, not commitment. He abandons his false belief and the negative behavior pattern it motivates. Not only does he fall in love, but for Marcus’s sake he also offers his friendship and emotional support to Fiona to help prevent her from attempting suicide again. In this way he demonstrates that he has learned the necessity of real, meaningful relationships. The film ends with all the main characters together in Will’s apartment–once his desert island paradise–sharing Christmas lunch. There is even a hint that Fiona too will find love. This ending marks a clear overturning of the rules of the normal world.

Two Minds, Positive and Negative Behaviors, False Belief, Normal vs. Possible Worlds: Maybe all character arcs don’t follow these principles. We’ll have to test them against many more movies. At least, though, they seem to offer widespread, enduring strategies for constructing character change.