Archive for August 2016

In pursuit of THE CHASE

The Chase (1946).

DB here:

While writing my book on Forties Hollywood, I often felt that every movie I talked about was based on a bestseller, a Broadway play, or something by Cornell Woolrich. Many of the best, or at least strangest, films of the era come from his haunted imagination.

T he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

Kino Lorber has recently released The Chase in a nicely cleaned-up DVD/Blu-ray edition. So all hail UCLA’s efforts restoring this neglected item, as well as its rescue of other worthy titles: Renoir’s The Southerner (1945, also from Kino Lorber), Too Late for Tears (1949), and Woman on the Run (1950), the last two from the estimable Flicker Alley. Kino Lorber has decorated the Chase release with commentary by Guy Maddin and recordings of two radio shows based on the Woolrich novel. (A pity we don’t have the Hedda Hopper radio show promoting the film, but maybe that’s lost.)

My book features The Chase because it poses with extreme prejudice the question of how far narrative innovation could go in the 1940s. Sometimes, as I’ve argued with The Great Moment and All about Eve, filmmakers go too far and get pulled back. But then readjustments necessary in postproduction may create twitches of novelty too. The Chase is another example of innovation by accident.

In the book, I mostly analyze the film. But I’ve also done a little digging into its production and promotion, as a way of explaining some of its captivating oddities. I came up with some information I haven’t seen discussed anywhere, so I thought I’d pass it along in a blog entry.

I haven’t located any scripts, alas, but our archive at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research holds other intriguing documents, including correspondence, a typescript synopsis, and a gorgeous presskit. Elsewhere I came across a document that gives clues about what the script and, at one stage, the film were like. There are reasons to think that an early version of the film was even stranger than the finished movie.

There must be spoilers, for both The Chase and The Woman in the Window (1944). Oddly enough, as we’ll see, contemporary reviewers of these movies didn’t worry about spoilers, so maybe I shouldn’t either.

Die in Havana, wake up in Miami

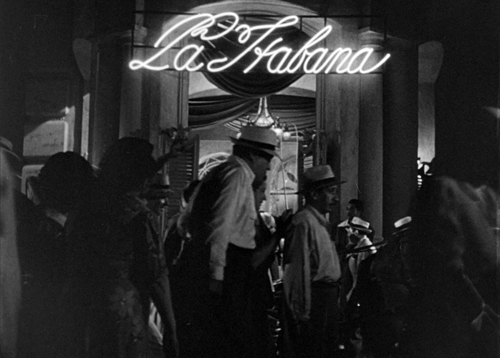

The Black Path of Fear begins in a fraught situation. Bill Scott enters a Havana club with an American woman. As they kiss, she is suddenly stabbed to death, and he’s the prime suspect. He escapes from police questioning and takes refuge in the tenement apartment of another woman, nicknamed Midnight. Scott recounts his backstory in a brief flashback, and then he sets out to find the people who have killed his woman and framed him. His effort takes him into the opium racket run by Eddie Roman from Miami. The bulk of the action takes place in Havana, with the flashback and a penultimate episode set in Miami.

The Chase shifts the book’s flashback material to its chronological place. The film begins with navy veteran Chuck Scott down on his luck. He finds a wallet belonging to crooked businessman Eddie Roman, returns it, and for his honesty is rewarded with the job of a chauffeur. He meets Eddie’s wife Lorna, and soon they are plotting to run away to Havana.

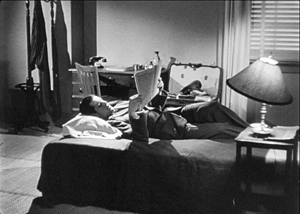

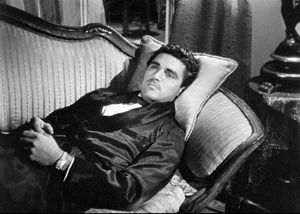

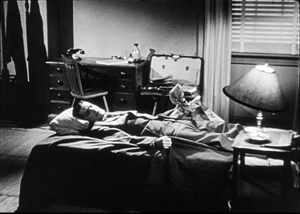

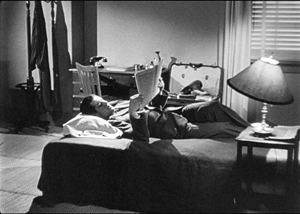

That’s when things get strange. On the night of the couple’s planned escape, Scott stretches out to read a newspaper. Fade out and up to Eddie, also stretched out, listening to a phonograph record–first in extreme long shot, then in mid-shot.

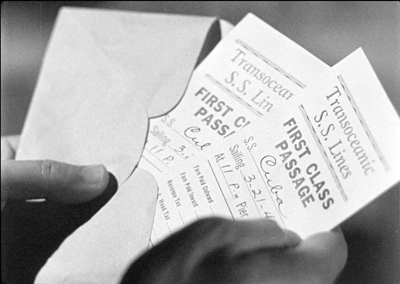

Eddie’s assistant Gino comes to Scott’s room and finds him gone. He reports to Eddie, showing the telltale travel folder.

As the recorded music continues, we are taken to a ship, where in a stateroom Scott is playing the same tune on a piano. Lorna is with him and they are evidently on their way to freedom.

Once the lovers are in Havana, The Chase follows the original novel, up to a point. Lorna is stabbed to death in the bar, Scott becomes the main suspect, and he flees the police by hiding in Midnight’s apartment. Soon Scott discovers that Gino is in Havana. He has arranged Lorna’s murder and the frame-up of Scott.

But now comes an astonishing twist, not in the novel. Gino finds Chuck hiding behind a curtain, shoots him, and dumps his body down a trap door. The body lies lifeless on the stair.

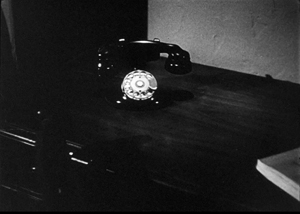

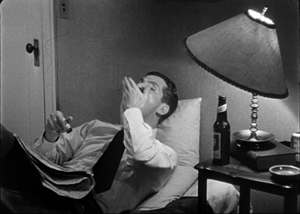

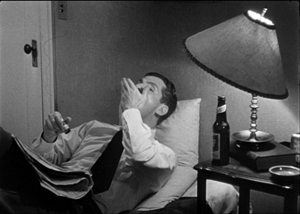

This is plotting in extremis. An hour into the film, both heroine and hero have evidently been killed and the unsavory characters have won. How to get out of this impasse? A telephone in the cellar rings. Cut to a ringing telephone on a desk, and track back. Chuck Scott is waking up, still on his bed with his newspaper.

He has dreamed the entire thirty-minute escape to Cuba, and we weren’t told he had fallen asleep.

This is the sort of twist modern filmmakers don’t advertise in advance, and indeed online accounts of the Kino Lorber disc, such as the shrewd review by Glenn Erickson, have been admirably discreet about it. Yet contemporary reviews openly revealed the device. Six out of seven trade-paper reviews I’ve found announce the dream twist. Daily Variety claimed that this “wild and disordered narrative” consumes “more than half the picture” (no) and “throws audience for a loss” (yes). Motion Picture Herald was less condemnatory—“the whole tangle untangles in a satisfactory manner”—but somehow found that Scott “has been dreaming a dream inside of a dream.”

Critics in the general press were likewise unafraid of spoilers. Life was a bit coy: “Its highly improbable plot has the eerie sensation of a bad dream.” The New York Times was more explicit: “All the foregoing horrors, however, are only a nightmare of Cummings’ ailing brain.” Of the violence, the Los Angeles Times noted, “Most. . . occurs in a dream sequence, which proves puzzling at first….” So perhaps some audiences, primed by reviews, were actually waiting for the twist. The film’s presskit does include suggestions for dream stunts exhibitors might try.

In any case, the dream has taken its toll on Chuck. Now he has amnesia, which spread among 40s movie heroes like a plague. Forgetting his promise to help Lorna escape, forgetting even how he got the chauffeur job with Eddie, he returns to his navy doctor for help. “It’s happened again,” Scott tells him. Dr. Davidson says he has “anxiety neurosis,” dismisses the Havana material as “dream-stuff,” and reassures him that he’s getting better. But from the spectator’s standpoint, the entire plot is put on hold.

The climax carries coincidence to new heights. Dr. Davidson takes Scott to a restaurant for a drink. Pieces of Chuck’s memory return, chiefly the name Lorna. At that moment Eddie and Gino stroll into the restaurant, having locked up Lorna at home. As Davidson chats with Eddie, Chuck finds the tickets to Havana in his pocket and remembers more. Rushing to Eddie’s mansion, he frees Lorna and takes her to the ship. Eddie learns of their plan and races to get to the pier, but en route his car is struck by a train.

Unlike Woolrich’s novel, The Chase takes place almost wholly in Miami, with the Havana dream as an interlude. The epilogue returns to the Havana nightclub and Chuck and Lorna in a carriage at the curb. As they embrace, Chuck says, “We’ll be together forever.”

There doesn’t seem to be any beginning

The Chase, released 22 November 1946, followed a series of and-then-I-woke-up pictures: The Woman in the Window (1944), The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945), and Strange Impersonation (March 1946). All of these thrillers depend on a double bluff. They seamlessly move from waking life to a dream scenario without tipping us off. They return to real life in a symmetrical fashion, while letting us observe how we were misled.

Hooks are very helpful here. For example, in The Woman in the Window, Professor Wanley asks a club servant to remind him when it’s 10:30. He settles down to read. Dissolve to the clock chiming 10:30.

Wanley is still reading when the servant’s voice from offscreen tells him the time. The camera pulls back as the servant enters the frame.

The transition is imperceptible. At the climax of the dream, when Wanley has sought to commit suicide with an overdose of sleeping powder, we get a parallel situation: He’s seated in a chair at home, and the camera tracks in. He seems to die, as the lighting changes.

But the servant’s hand comes in to shake him, he awakes, and we hear the club clock chiming 10:30. The camera tracks back, and the glass in Wanley’s hand in the dream has become the sherry glass he held in the framing scene.

Like its predecessors, The Chase doesn’t signal its dream transition. No whirling superimpositions lead into it, no outlandish compositions announce that we’re in the middle of it. (For comparison, see Stranger on the Third Floor, 1940.) As in The Woman in the Window, the shift is cunningly concealed. Here offscreen music on Eddie Roman’s phonograph is continued as an auditory hook into the start of the dream.

In retrospect, we might argue that the Havana episode hints at its subjective status. Chuck yawns slightly as he’s reading his newspaper, though I don’t think most viewers take that as a dream cue. The concerto music, issuing from a phonograph in Eddie’s living room, is, implausibly, picked up by Scott, who plays the tune on board the ship. The light falling on Lorna and Scott in their cabin is markedly unrealistic, with a shadow dropping and rising on the porthole.

Scott tells Lorna to “Forget time,” and the song to which the couple dance in the club contains the line, “Like the stars in a dream song.” And when Dr. Davidson asks how it all began, Scott replies: “There doesn’t seem to be any beginning”—as if acknowledging the surreptitious segue into his imaginings. The Chase wouldn’t be the first 1940s film to flaunt its own artifice.

The Chase revises the dream schema in a couple of intriguing ways. For one thing, The Woman in the Window and Strange Impersonation make the dream the bulk of the film; the lead-in and lead-out are fairly perfunctory. Many other films make the dream a brief one, enclosed within long stretches of real-life action. The Chase gives us something midway between, a thirty-minute dream that functions as a block almost exactly equal to the chunk of real-world action that precedes it. We have to trace our steps backward to an earlier point of departure and then reckon how new action connects to it. Something similar happens with Uncle Harry, but there the dream comes so late as to supply the film’s climax.

Moreover, in the other films, the dream doesn’t actually alter the real-world situation that gave birth to it. Here, though, the dream has a causal function: It triggers the recurrence of Chuck’s amnesia.

The Chase goes a little farther than its predecessors in another way, The other films in the cycle keep the visual narration attached to the dreamer before and after the transition; that is, the dream’s first scene shows us the dreamer continuing to act. Both Woman in the Window transitions keep us fastened on Wanley. But the first scenes in Scott’s dream feature not Scott but Eddie and Gino. We accept this shift of attachment partly because from the start the film’s narration has been fairly unrestricted, crosscutting between Scott and Eddie. Early in the dream, this departure from Scott’s range of knowledge seems to confirm the objectivity of what follows.

Scott, it turns out, can dream what the bad guys are doing, and because of this we can get a moment of even sneakier duplicity. Within the dream, Gino finds Chuck gone. The beer bottle and discarded newspaper help reaffirm the reality of the scene because an earlier scene of Scott rising included the same props: the beer bottle on the nightstand, and a newspaper in Chuck’s lap.

With the turn to the amnesia device, things become no less dislocated. After Scott visits Dr. Davidson, he becomes surprisingly telepathic. When Eddie learns that Lorna wants to leave, he beats her and locks her in. Dissolve from her sobbing on the floor to Chuck at the bar, staring into space and remembering her name.

Immediately after we’ve seen Eddie’s car smashed by the train, Scott is waiting with Lorna in a stateroom that recalls the dream flight. He’s seized by a calm confidence, as if he intuited their salvation. “It doesn’t matter now.” From that we segue to the two kissing in the carriage outside the Havana club.

For all its attractiveness, Scott’s Cuban adventure doesn’t resolve the main plot. It postpones the Miami action by motivating his new bout of amnesia. Once Chuck loses his memory and flees Eddie’s house, the couple’s planned escape is scotched and the film has to start over by introducing a new character, the therapist Dr. Davidson, and relying on massive coincidence to bring Eddie and Gino back into the action. Perhaps this is why trade critics complained that the last stretch of the film was clumsy.

The case of the missing flashback

So far, so weird. But I think that an earlier state of The Chase was even weirder.

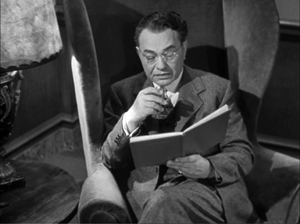

First, some background. Judging by the press coverage, it seems that the figure of authority on the film was the producer Seymour Nebenzal (below). He was a venerable figure, having produced many German classics—M (1931), The Threepenny Opera (1931), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933)—before fleeing the Nazis. He spent some years in France, producing among other films Mayerling (1936) and Ophuls’ Roman de Werther (1938). Emigrating to the US, he continued to work as an independent producer, with such films as We Who Are Young (1942), Prisoner of Japan (1942), and the Sirk films Hitler’s Madman (1943) and Summer Storm (1944).

Screenwriter Philip Yordan had bought the rights to Maritta Wolff’s 1941 novel Whistle Stop, prepared a screen adaptation, and sold the whole package to Nebenzal. Nebenzal had just reconstituted his Weimar company Nero Film, and Whistle Stop (January 1946) was its first release. Yordan applied the same packaging strategy to The Black Path of Fear. He bought the rights to Woolrich’s novel, then sold them and his adaptation to Nero. Director Arthur Ripley became involved after halting work on his adaptation of Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel.

Yordan was said to have had a financial interest in the film, and apparently Nebenzal promised him the credit “Philip Yordan’s The Chase,” which didn’t come to pass. Most of the publicity spotlighted Nebenzal, who was credited with many of the creative decisions.

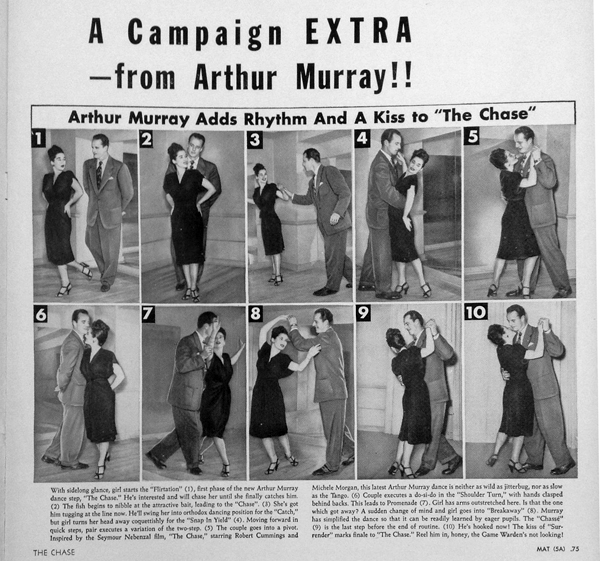

The Chase was not a low-budget project. It was promoted and distributed as an A picture. Boxoffice, the exhibitors’ trade paper, called it a “grade-A gripper, aimed at class houses.” The presskit reveals a tie-in with the Arthur Murray dance studios, which would teach patrons a new step, “The Chase.” (See at very bottom.) At worst the picture might function as a “nervous A” because of the relatively second-tier status of its stars (though Robert Cummings had profit participation in the project).

The production budget, according to an October 1947 financial statement in the WCFTR Collection, was $898,300.60. That doesn’t include debt service of about $40,000. In public statements, Nebenzal claimed that he boosted the film’s budget to $1.2 million. In all, these figures are in line with a mid-range A picture for the period; the average negative cost for all feature films in 1946 was $665,863 (in an era with a lot of B’s at $300,000 or less).

As befits its budget, The Chase contains solid miniature work and big sets, like Eddie Roman’s mansion and the Habana Club. Reviews praised its high production values, achieved by shooting at the Goldwyn studio. There are a couple of impressive crane shots, and Daily Variety reported that three camera booms were used on some scenes. There was time for finicky reshoots during and after principal photography.

In the course of production, Nebenzal issued a stream of press releases. The most important for our purposes appeared in Daily Variety of 16 September 1946.

Producer Seymour Nebenzel, believing market is glutted with flashback pictures, has ordered film editor Edward Marin to eliminate flashback sequence in Robert Cummings starrer, “The Chase.” Script was written so action could start from scratch, instead of starting with chase and then flashing back to start of action, as is done in the Cornell Woolrich novel.

Huh? What flashback?

When I found this item some years ago, I thought: Of course. The novel has a flashback to Miami, and the film moved it up to be part of the opening Setup. But then I realized: The flashback to Miami would have made sense only if the bulk of the film’s action were in Havana. But the film as we have it curtails the novel’s Havana action—most drastically, by killing off the protagonist. Was it possible there was a whole alternative film in which Scott survived and tracked down Roman’s opium-smuggling ring, as in the book? Was all that footage shot but jettisoned?

More likely, the bulk of the action was always going to take place in Miami. (The chase is a relatively small part of The Chase.) For one thing, Jack Holt was signed to play Davidson in early July. Davidson is the catalyst for the action leading to the climax, so once Holt was aboard, the final stretch of the film seems locked to Miami.

So maybe Nebenzal’s remark about taking the “flashback” out was just loose talk. He did display a general pattern of shilly-shallying. He publicly pondered, for instance, whether Lorna should live or die. He claimed to have requested two versions of the script: one in which Lorna remains dead at the end (as in the novel) and one in which she isn’t really dead (to be managed somehow). He said he’d leave it to preview audiences to decide.

This seemed to me a big tease. Nebenzal originally wanted Joan Leslie for the part and pursued her intently before discovering that she was unobtainable. Michèle Morgan, though a minor figure in the States, was a star in France; she won an acting prize at Cannes shortly before The Chase was released. By the fall Nebenzal sought to sign her to a longer-term contract. Keeping Lorna alive for more screen time, as happens in the film’s final Miami section, would be a good buildup for Morgan. In an April press release, Nebenzal had already seemed inclined toward letting Lorna live.

“After all,” he reasoned, “people want to be relieved of their daily troubles when they go to the movies. They don’t want to see their favorite actor or actress killed off.”

By September, Lorna definitely survived. Another press release:

Seymour Nebenzal shot 3 endings for “The Chase,” showing Robert Cummings and Michèle Morgan fleeing by land and sea. One ending had them scramming aboard ship, another on a train, the third on a bus. So far the bus flight is favored.

The shipboard option was chosen, obviously, but the mention of alternative escape vehicles entails that by early September, Lorna was intended to survive one way or another.

All this on-again, off-again made me disregard the item about “eliminating the flashback” as guff or misreporting. That was a mistake.

The film beneath the film

Then as now, one way to promote a new Hollywood release was to publish a novelization: not the original book that the film was based on, but a new literary text derived from the film. As I write this, Alexander Freed’s novelization of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story is available for preorder. Then as now, the novelization would be timed to arrive when the film was released.

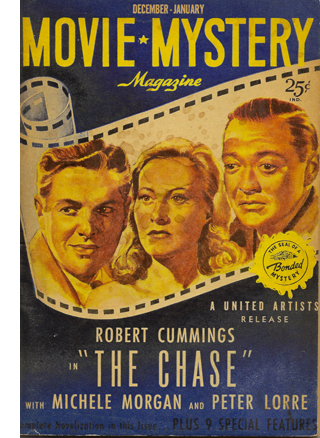

In late June Nebenzal told United Artists officials that he had arranged for a “fictionization” of The Chase, to be published in Movie Mystery Magazine. That periodical’s inaugural issue, dated December-January 1946, did appear on newsstands in November, during the film’s release.

In late June Nebenzal told United Artists officials that he had arranged for a “fictionization” of The Chase, to be published in Movie Mystery Magazine. That periodical’s inaugural issue, dated December-January 1946, did appear on newsstands in November, during the film’s release.

Novelizations, then as now, were typically prepared not from the finished film but from a script or treatment. And indeed Nebenzal indicated in his letter that he would be sending the magazine a copy of the script. It seems likely, then, that the version of the film “fictionized” in MMM reflects the state of the script in the summer of 1946. If we read the MMM version, what do we find?

We find a narrative structure that’s far more peculiar than the finished film. Here’s how it goes.

The novelization starts with Chuck and Lorna in Havana, en route to their ship. Their carriage stops at the La Habana club, they go in for a drink, and Lorna is stabbed. Arrested, Chuck escapes from the police and takes refuge with Midnight in the tenement. She asks him what brought him to this pass, and in a flashback he tells her. This takes us back to Miami, where he finds Roman’s wallet, meets Lorna, falls in love, and flees with her. The flashback ends with the couple in their cabin aboard ship.

All this conforms to Woolrich’s book, and it strongly suggests that Nebenzal wasn’t blowing smoke when he said in September that he was making the editor “eliminate the flashback.” Evidently Chuck’s flashback existed in both a shooting script and an early version of the film. Its position must have been fairly firm for some time, if as late as September Nebenzal could move it to the front of the film.

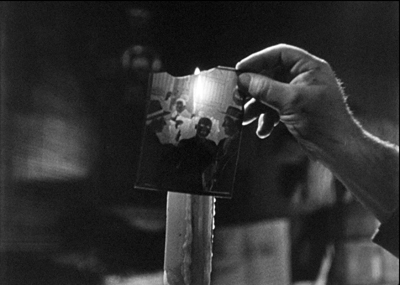

Does the novelization follow the Woolrich original after the flashback closes? It does up to a point. From the scene of Chuck and Lorna in their cabin aboard the ship, we return to the present, in Midnight’s apartment. There she advises Chuck on how to investigate Lorna’s death. He finds the photographer dead. Then comes the deviation. Chuck discovers Gino at Mrs. Chin’s shop, burning the incriminating photograph. In the novelization, Gino beats Chuck unconscious and dumps his body down to a cellar.

Now for the big twist. Chuck wakes up in his room in Roman’s mansion. Scott is now back in Miami, completely befuddled. All he can do is stumble to the phone, take some pills, and call Dr. Davidson. The novelization goes on to adhere pretty closely to the rest of the film as we have it.

In the novelization, in other words, the entire action up to this point, in both Havana and Miami, has been Chuck’s dream. Here’s the outline, just to be clear. What’s in green is veridical, what’s in red is not.

{Chuck’s dream begins: No front framing situation.}

Havana (dream): Lorna murdered at the Habana club, Chuck flees, and he meets Midnight. This contains:

Miami flashback (accurate up to the couple’s flight): Chuck hired by Eddie, meets Lorna, escapes with her on ship.

Havana (dream): Chuck investigates, is killed by Gino.

Dream ends: Chuck wakes up in Miami with amnesia.

Chuck goes to Dr. Davidson, who takes him to bar. Chuck rescues Lorna, and Gino and Eddie die in crash.

Epilogue: Couple freed, en route to Havana on ship.

Two things make this pattern striking—one minor, one pretty scandalous.

First, there’s no “front frame”: no situation that puts Chuck in a pre-dream reality. By convention, we don’t have to see him actually fall asleep, but it’s usual to provide circumstances that we can understand retrospectively as preparation for sleep. This is what we get in The Woman in the Window and other then-I-woke-up films. But this movie starts inside the dream.

Nowadays, of course, we’re used to sequences in which a dream is signaled only after the fact. In Out of Sight (1998) we see Karen Sisco sneak up on Jack Foley and then fall to kissing him in his bathtub; then the scene is revealed as a dream. But in the Forties, and even today, it wasn’t usual to have a dream launch the film and go on for over fifty minutes before revealing itself as a dream.

Second, the scandalous aspect. In the novelization’s version of the plot, and presumably the script and an early draft of the film, the dream includes the flashback to Miami. The framing dream material is fantasy, but the flashback is for the most part veridical. Eddie, Gino, Lorna et al. really did most of what we see them doing, even if the encounter with Midnight, the Habana murder, and Chuck’s fight with Gino aren’t real. The only stretch of the Miami flashback that isn’t real is the couple’s flight (which hasn’t happened yet in the waking world).

Here’s why, I suggest, we get those two lines when Chuck visits Davidson. “There doesn’t seem to be any beginning,” Chuck says. Right: because we never saw a beginning, an opening frame for the long dream stretch. And Davidson is at pains to reiterate that the Havana adventure is “dream-stuff” while Roman and Lorna are definitely real. Davidson’s remarks would have served as redundant confirmation for the audience that most of the Miami flashback could be trusted.

During the 1940s, filmmakers competed to find outlandish variants on subjective viewpoints, dreams, and flashbacks. Embedding real scenes as a flashback within a larger, definitely unreal but unmarked dream constitutes a genuine, if screwy innovation for the era.

Fixing it, sort of, in post

On all this circumstantial evidence, I surmise that the novelization’s weird structure was in the script as planned and in the film as initially shot during the summer of 1946. At some point, however—perhaps after previews—Nebenzal thought the better of it. He instructed the editor to move the Miami flashback to the front of the film, where it serves as a conventional chronological introduction to the action. But now what do you do with the Havana stuff? Are you going to kill off Lorna?

No. Clearly Nebenzal and his team had decided to keep the dream idea, but confine it wholly to the Havana episode. That allows Lorna to live at the film’s close. But now they would need to set up the dream within the Miami stretch. So they provided a frame that’s not in the novelization: the scene of Chuck stretching out on his bed as an equivocal prelude to the dream. In other words, a reshoot was called for.

Correspondence between Nebenzal and Paul Lazarus, Jr., head of advertising for United Artists, suggests considerable last-minute reworking. Nebenzal, invited to show some reels at a 19 August New York City trade event, declined, saying that nothing was in final shape. Having agreed to come to the event, he then demurred, saying he needed to start retakes on Monday 12 August. He promised to deliver the film “beginning of September,” but midway through that month he was shooting three endings, announcing a budget increase, and claiming he was eliminating the flashback. Not until 7 October did Lazarus finally get to see the film (which he praised). The trade press viewed The Chase on 11 October: a tight squeeze.

These events suggest that having decided to eliminate the flashback, Nebenzal arranged reshoots and postproduction adjustments to set up the dream with framing scenes in Chuck’s bedroom. Interestingly, those framing scenes show the bedroom as slightly different than we’ve seen it earlier. The lead-in to the dream shows the room as it looks in the later waking-up scene.

These show consistent placement of the phone on the desk, along with a chair and Chuck’s suitcase open on it. But earlier views of the room include different furnishings–no second chair by the desk, a floor lamp, a wastebasket by the bed, the phone in a different spot, a book supporting Chuck’s bedside lamp.

No big deal, of course; these shots are from earlier in the story than the night of Chuck’s departure. The hitch is that when Gino comes in after Chuck has left (that is, following Chuck’s lying on the bed in the first shot above), the room is as it was in the earlier scene. In the shot before Gino enters, we can see there’s no extra chair, all the stuff on the night table is as earlier in the film, and the Schlitz bottle is there–as it isn’t when Chuck stretched out before his departure, or when he wakes up thereafter.

The dream presentation of the room is identical with the earlier purportedly non-dream room. (As you’d expect if both setups were once part of the “real” flashback.) But those views are not identical with the look of the room when the dream began.

I’m not suggesting that the audience would notice these continuity lapses. I’m suggesting that they’re evidence of an imperfect reshoot. Here it appears that both the entry into the dream and the movement out from it weren’t filmed as they would normally be: in conjunction with the other scenes in the same set. It seems that some time after doing the first round of bedroom scenes, Nebenzal rebuilt or redressed the set and shot the first frame situation, that of Chuck going to sleep, and at the same time shot the closing situation, of him waking up. Nebenzal may have had one version of the wakeup scene already, since it was required by the earlier screenplay version. But perhaps he hadn’t completed it yet, or perhaps he just reshot it in the redressed set to be on the safe side. As far as I can tell, all the shots during Chuck’s return to consciousness are filmed in the redressed set, the one with the open suitcase.

I suspect that there was a change in the Havana sequence too. The novelization doesn’t have Chuck murdered, only struck unconscious. The film as we have it revises that to a kill. But the manner of presentation of his death—behind a curtain, with offscreen gunshots and an odd axial cut to the curtain—suggests some adjustment in production or postproduction. If the reshoot did have Chuck killed rather than clobbered, the change drives home the irreal nature of the dream. Nothing proves itself a fantasy more vividly than killing someone off in it and then revealing they’re still alive.

Endless love

If I’m right, the most ambitious storytelling innovation of the project, the veridical flashback swaddled inside an irreal dream sequence, was scotched. There are other incompatibilities between the finished film and production documents.

For example, The Black Path of Fear includes a moment when, after Lorna and Scott have escaped to the boat, they receive a telegram with a single message: LUCK. –ED It’s meant to suggest that Roman is aware of where they are and where they’re going, thus amping up the suspense. This moment is replicated in the MMM novelization, the typescript synopsis, and the synopsis in the presskit.

In the novelization, Scott burns the telegram. The moment is missing from the film, but something like this scene seems to have been planned for Chuck’s encounter with Midnight. Daily Variety reported:

Toughest camera job of the week, according to Franz Planer, lens chief for Seymour Nebenzal’s “The Chase,” is keeping the camera in focus during a 90-degree angle pan from a cablegram burning on top of a stove to a scene between Robert Cummings and Yolanda Lacca in a Havana tenement flat. It took 20 takes to get a perfect shot. The shot got added complication from the intense heat and the fact that the cameraman had to keep his eye glued to the eyepiece while moving from standing to sitting position.

This suggests that the film showed Chuck burning Roman’s message not with Lorna on shipboard but with Midnight in her apartment. The burning telegram might even have been a transition out of Chuck’s flashback explanation of what happened in Miami. That’s pretty speculative on my part, but here’s something more plausible—a fairly clear byproduct of all the last-minute reshuffling of scenes.

Once Eddie and Gino have been killed on the highway, we could end the film by showing Scott and Lorna embracing in their cabin, this time headed for Havana. That’s in fact the way the novelization and the synopses end. The film adds an extra epilogue of Eddie and Lorna embracing in the carriage outside the club. These shots are plainly recycled from early footage. Perhaps there was no suitably romantic footage of the couple’s reunion on shipboard. The shots we have don’t seem especially intimate, certainly not typical of a finale.

Or perhaps Cummings and Morgan were unavailable for retakes.

In any case, by providing the scavenged tag we have, the film raises the question: How can the real nightclub we see in the epilogue’s happy ending be, in a sort of Buñuelian recursion, the same one that Scott dreams in advance? How did Chuck know the very same bored driver would be there? The question becomes more pressing because the situation at the end seems to replay an exact moment in the dream, when the couple embrace in a carriage before going into the club. The carriage shots in the dream and in “reality” are uncannily similar. All that’s varied from the earlier scene is the order of the shots.

The last scene continues the romantic dialogue of the first Habana visit, as if nothing had happened in between. And the epilogue even uses a line that was in the opening of the novelization, and perhaps the screenplay: Chuck says he will love Lorna forever.

Maybe the filmmakers thought that audiences wouldn’t notice the near-identity with the earlier scene, and would just take it as Hollywood’s familiar here-we-go-again gimmick. But the effects are disconcerting. This nearly identical replay gives Chuck’s dream the power of prophecy. Or perhaps this last scene just starts the dream over again—and leads to the same fate for Lorna. The dream may have taken away Scott’s immediate memory of his affair with Lorna, but it has given him, through the film’s recycling of motifs, an uncanny power over the final bit of the narrative. He can intuit Eddie’s death and revisit in reality the scene of passion and murder he imagined. Were these associations fully intended by the filmmakers? Say rather that by shuffling together, somewhat desperately, characteristic 1940s devices, The Chase takes us into a winding labyrinth of alternative stories.

A later entry on the film offers some more evidence for the production changes that resulted in its peculiar structure.

First, many thanks to Mary Huelsbeck, Assistant Director of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, for helping me find valuable documents in the United Artists Corporation Records. It would be too lengthy to cite all the specific items I used, but the principal ones are in Series 3A: Producers Legal File, 1933-1936; Series 4D: The Paul Lazarus, Jr. Files, 1943-1949; and Series 5.3: United Artists Dialogues, 1928-1956.

The most important press releases are the one about the three endings, in “”Just for Variety,” Daily Variety (3 September 1946), 4, and the one about the elimination of the flashback, in “Hollywood Inside,” Daily Variety (16 September 1946), 2. The film reviews I’ve quoted are “The Chase,” Daily Variety (14 October 1946), 3; “The Chase,” Motion Picture Herald (19 October 1946), 3262; “Movie of the Week: The Chase,” Life (11 November 1946), 137; Archer Winsten, “Chase through a Maze,” New York Times (18 November 1946), 39; John L. Scott, “‘The Chase’ Suspenseful,” Los Angeles Times (25 January 1947), A5.

The Movie Mystery Magazine version includes some passages not in the final film, including internal monologues, flashbacks, and a delirious montage when Chuck is on his way to see Dr. Davidson. These are all pretty common techniques of the period, so it’s possible that the script, or an earlier version of the film, contained them.

Philip Yordan doesn’t have anything to say about these matters in the published interview with Pat McGilligan in Pat’s Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s (University of California Press, 1991), 330-381. Yordan’s screenplay collection at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences apparently doesn’t include The Chase. Of course, if anyone knows where a script of the film may be found, I’d be grateful to learn of it.

I haven’t mentioned one of the strangest items in the film. Eddie Roman is the ultimate backseat driver, and he has installed an accelerator and clutch back there that allows him to override the driver’s control and speed up at will. He uses the gadget to test Chuck’s nerves during an outing, and it becomes the means by which he inflicts death on himself and Gino during their race to the dock. Me, I think it would have been a better payoff to let Chuck and Lorna, trussed up in the back seat while Eddie is driving, use the same mechanism to force the car to crash. But The Chase is the sort of movie that makes you spin off alternative scenarios as you please.

For in-depth information on Cornell Woolrich, the definitive source is Francis M Nevins, Jr.’s Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (New York: Mysterious Press, 1988). Not a bad title for The Chase, actually. For more on flashback construction in the 1930s and 1940s, see “Grandmaster Flashback” and “Chinese boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies.”

The Chase (1946) United Artists pressbook.

Is there a blog in this class? 2016

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991).

KT here–

Another year has passed, and Observations on Film Art is approaching its tenth anniversary. The blog was never intended as a formal companion to our textbook Film Art: An Introduction. Basically we write about what interests us. Still, many of our entries use concepts from the book, and we hope that teachers and students might find them useful supplements to it.

As each summer approaches its end and teachers compose or revise their syllabi, we offer a rundown, chapter by chapter, of which posts from the past year might be relevant. (For previous entries, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015.) For readers new to the blog, these entries offer a way of navigating through the site.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Film projection made the national news in late 2015 when Quentin Tarantino released his new film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film. Only 100 theaters in the USA, most of them specially equipped with old, refurbished projectors, could show it that way. We went behind the scenes to see how the theaters coped in THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth and THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing.

This year the studios took tentative steps toward instituting The Screening Room, a system of streaming brand-new theatrical films to people’s homes for $50. Whether or not this service succeeds, it represents one new distribution model that Hollywood is exploring to cope with the increasing delivery of movies via the internet. See Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop.

Popular film franchises can go on generating new products and influencing other films for years. We examine the lingering impact of The Lord of the Rings thirteen years after the third part was released in Frodo lives! And so do his franchises.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In this chapter we put considerable stress on the concept of narration, the methods by which a film conveys story information to the viewer. There is no end to the ways in which narration can be structured. Often one of the characters in a film can to tell us what happened. . . even if that character is dead. This, as we show in Dead Men Talking, is not as rare as one might expect.

The Walk combines narrative and genre in an unusual way. The first part is a romantic comedy, the second a suspense film, and the third a lyrical piece. We suggest why in Talking THE WALK.

The way a film tells its story can vary considerably depending on whether it has a single protagonist, a dual protagonist, or a multiple protagonist (as in The Big Short, bottom). We examine some of the differences in Pick your protagonist(s).

Looking back over our blog as we passed 700 entries early this year, it occurred to us that several entries discussing principles of storytelling could be arranged to create a pretty good class in classical narrative strategy. We made up an imaginary syllabus in Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101. No tuition charged.

With the very end of the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise–the release of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third Hobbit film–we discuss the strengths of the film and the plot gaps left unfilled in A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

To celebrate Orson Welles’s 101st birthday, we examined some of the sources for some of the techniques used in Citizen Kane, a film we analyze in detail in Chapters 3 and 8. See Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts.

In Hollywood it is a common assumption that the protagonist(s) of a film must have a “character arc.” Filmmaker Rory Kelly, who teaches in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, wrote a guest entry for our site. Rory analyzes the character arc in The Apartment, with examples from Casablanca, Jaws, and About a Boy as supplements. See Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly.

James Schamus’ Indignation, an adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, draws on novelistic narrative devices not in the original. In INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film, we suggest that those devices first became standard in cinema during the 1940s.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

Teachers and students always want to us add more about acting to our book. It’s a hard subject to pin down. We introduce the great stage actor Mark Rylance, who was largely unknown outside the United Kingdom before he won an Oscar for Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, and discuss how he achieves his expressively reserved performances in that film and the series Wolf Hall. See Mark Rylance, man of mystery. (Above at left, on set with Tom Hanks and Spielberg.)

In an era when most staging of actors in movies follows a few simple conventions, we examine the more imaginative ways of playing a scene on display in Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950) in Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers young and old.

Continuing with the theme of acting and staging, our friends and colleagues, Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have put a revised version of their in-depth study of silent-cinema acting online for free. Learn about it and the enhancements that internet publishing has allowed in Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

We look at the visual style of Anthony Mann’s Side Street (1949) and show how a simple, seemingly minor technique like a reframing can create a strong reaction in the spectator. See Sometimes a reframing …

Framing a composition is one of the most basic aspects of cinematography. We discuss centered framing, decentered framing, balanced framing, framing in widescreen movies, and particularly framing in Mad Max: Fury Road (above) in Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom.

In a follow-up entry, we discuss framing in the classic Academy ratio, 4:3, with emphasis on action at the edges of the frame: Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket.

Chapter 7 Sound in Cinema

For the new edition of Film Art, we had to eliminate our main example of sound technique, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige. But we put that section of the earlier editions online. THE PRESTIGE, one way or another takes you to it.

For those who have been looking for examples of internal diegetic sound, we take a close look (listen) at a sneaky one in Nightmare Alley: Do we hear what he hears?

The fact that the protagonist narrates The Walk in an impossible situation, standing on the torch of the Statue of Liberty and talking to the camera, bothered a lot of critics. We suggest some justifications for this decision in Talking THE WALK.

We offer brief analyses of the Oscar-nominated music from 2015 films in Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Many different filmic techniques can serve similar functions. Filmmakers of the 1940s had a broad range to choose from when they portrayed dead people, or Afterlifers, on the screen. We look at how their choices affected the impact of the scenes (as in Curse of the Cat People, above) in They see dead people.

Style and form in three films of Terence Davies: Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes; and especially his most recent work, Sunset Song. See Terence Davies: Sunset Songs.

Style and form in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, on the occasion of its magnificent release by The Criterion Collection, in A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY: Yang and his gangs.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated

Leo Hurwitz’s little-known documentary, Strange Victory (1948) has recently come out on Milestone’s DVD/Blu-ray. Released shortly after the end of World War II, it suggests that the Nazi atrocities were only an extreme instance of the cruelty of racism. We discuss the film and its relevance to the current political situation in Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948).

Experimental filmmaker Paolo Gioli makes films without cameras, or at least, he cobbles together pinhole cameras of his own from simple materials. The results are remarkable. We describe his work and link to a recent release of his work on DVD in Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

The eleventh edition of Film Art contains a new sample analysis of Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom. We discuss some additional aspects of the film in Wesworld.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

At the end of each year we avoid doing a standard ten-best list by choosing the ten best films of ninety years ago. For 2015, we dealt with The ten best films of … 1925 (including Frank Borzage’s Lazybones, above). It was a very good year.

A rare French Impressionist film, Marcel L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine, has been released on DVD/Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. We discuss the film and its background in L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema.

Film Adaptations

Our eleventh edition offers an optional chapter on film adaptations from a wide variety of art forms and even objects.

For thoughts on popular female novelists whose books were adapted into films during the 1940s and 1940s (and who sometimes became screenwriters), see Deadlier than the male (novelist).

Adaptations can be made from nonfiction as well fictional books. We look at how Dalton Trumbo’s life was made into a biopic in Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO.

In a series of entries, we have commented on the adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit into a three-part film. For an analysis of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third part, see A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump? (Links in that entry lead to earlier posts on this subject.)

As always, we have blogged about some recent books and DVDs/Blu-rays. See here (Vertov, sound technology, 3D), here, (Kelley Conway’s new book on Agnès Varda), here (experimental films, the first Sherlock Holmes, the Little Tramp), here (Tony Rayns on In the Mood for Love), and here (on some older foreign classics that have finally made it to home video in the USA, primarily those of Hou Hsioa-hsien). The publication of the eleventh edition of Film Art led us to look back on how it was written and some of the ideas that went into it. We took the occasion to introduce our new co-author, Jeff Smith. See FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

We were also profiled in Madison’s local free paper, Isthmus, by Laura Jones, reporter and filmmaker. She read Film Art as a student.

The Big Short (2015).

INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film

Indignation (2016).

DB here:

As I finish my book on 1940s Hollywood storytelling, I see that period’s influence all over the place. (Actually, that’s part of the book’s point.) One thing that filmmakers did back then, I think, is make cinema more “novelistic.” It’s not just that they took stories from novels, though they certainly did. They also made much greater use of storytelling devices that had become common in literature both high and low.

Many of these techniques I’ve talked about in other entries. There were, of course, flashbacks—not new to the Forties, but now much more frequent than in the Thirties. There was also the rise of voice-over commentary, like the narrating voice of fiction. It might be the voice of an objective narrator, as in Naked City (1947). Or it might be the voice of a character, either telling the tale to another character, or recalling events purely in his or her mind.

Other types of subjectivity came forward too, such as dreams, daydreams, and hallucinations. Filmmakers of the 1930s were inclined to tell their stories objectively, through concrete behavior. But thanks to imported and revised literary strategies, many Forties films gain a greater density and interiority. Compare, for example, the 1931 Waterloo Bridge with the 1940 one.

One thesis of my book is that filmmakers of the Forties consolidated these strategies in a way that became central to modern movie storytelling. That seemed to me to be confirmed when I saw James Schamus’s directorial debut, Indignation, now or soon playing at a theatre near you. Because of his skill as a screenwriter, I expected an intelligent adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, but I also hoped to learn more about the expressive resources of contemporary cinema. I wasn’t disappointed.

Indignation’s core story involves Marcus Messner, studious son of a New Jersey butcher who goes off to a Midwestern college. Stuffed with ideas and ambitions, Marcus is intellectually worldly but socially and sexually naïve. If he weren’t in college, he’d be drafted to fight in the Korean War. Instead of fitting smoothly into academic life, he finds himself confused by Olivia Hutton’s calculated sexuality. In addition he struggles with an overprotective father and the puritanical, hamfistedly Christian, regimen of 1951 campus life.

To talk about what I find exciting and instructive in the film, I have to presume you’ve seen it. So what follows is filled with spoilers.

Sticking to one causal line

Like the book, the film is an exercise in restricted point of view. That involves not simply the voice-over commentary that weaves in and out. (In a film, that technique doesn’t guarantee restriction the way first-person narration would in a novel. Movies can be more promiscuous in breaking with what one character thinks and knows.) And the restriction isn’t wholly a matter of a subjective plunge either, though we do get Marcus’s dreams and fantasies and some fragmentary flashbacks.

No, what makes Indignation intriguingly “novelistic” is a matter of attachment. We’re simply with Marcus through almost the entirety of the movie. We know only as much as he knows. This means that we learn about certain things when he does. His father’s breakdown back home is conveyed through phone calls. At the climax, his mother’s visit to him in the hospital reveals that she’s considering divorce. An alternative narrative strategy would be to shift from scenes with Marcus to scenes elsewhere, say back home in New Jersey or in Olivia’s dorm. This “omniscient” option is more common throughout American film history; we see it in the crosscutting between CIA malefactors and poor David Webb in Jason Bourne.

Restricted narration isn’t the only way to generate mystery, but it’s a reliable one. By attaching us to Marcus’ range of knowledge, Indignation creates mysteries, chiefly around Olivia. What has made her behave as she does? She never offers a full explanation, but in some scenes she tells more about her parents and in a crucial confession she confesses her alcoholism, a suicide attempt, and a period in treatment.

During this confession, Schamus finesses the showing/ telling problem in an intriguing way. There are good reasons, I’ve suggested before, to let such monologues play out in the space and time of the scene. Telling is sometimes more vivid than showing. But Schamus has chosen to show as well as tell, by providing quick flashback illustrations of what Olivia recounts to Marcus.

What interests me is that these images from the past have an in-between status. They’re neither straightforward and neutral, nor Olivia’s own viewpoint, nor exactly Marcus’s imagined version of what she’s telling him. For instance, the straight-down, somewhat diagrammatic and clinical framing of some of them calls to mind the film’s first shot, also associated with Olivia’s health: the pill case in the care facility.

Likewise, the shot of Olivia in a straitjacket, framed off-center in a way few other isolated long shots in the film are, has an abstract quality that suggests an image lying somewhere between her memory and Marcus’s imagining of her situation—without making it wholly subjective. (In the early 1950s, it’s plausible she was indeed treated this way.)

At the climax, we get even less information about Olivia’s situation. Before Marcus can break off with her, she simply vanishes. Marcus will never find out what became of her. For him, if not for us, the mystery is permanent.

Not that he doesn’t try to communicate. This is one role of the voice-over in which he muses on his past and, more ambitiously, on the role of cause and effect in life. As a follower of Bertrand Russell, he’s evidently pondering Russell’s idea of “causal lines.” Ironically, though, Russell’s inferential model of causality doesn’t help Marcus figure out what happened to Olivia.

But from where is Marcus speaking? Quite likely, from the Afterlife.

Dead narrators drift through 1940s cinema. Philip Roth was ten when The Human Comedy (1943) featured a deceased father returning to his small-town family, and eleven when The Seventh Cross (1944) gave us an executed prison-camp escapee who shadows one of his mates. So Indignation, set in the year after Sunset Boulevard (1950), seems perfectly in keeping with this trend. But these other films announce the voice-over’s posthumous status right away. Schamus does something a bit different.

In the source novel, Roth lets Marcus suggest that he’s dead about a quarter of the way through. Schamus’s screenplay drops hints that are, I think, fully noticeable only in retrospect. He creates a surprise that in turn motivates one of the two frames that surround the 1951 story action.

The front end of the inner frame is a brief combat skirmish in South Korea. A GI is pursued into a dark, nondescript building by a North Korean soldier. The action is difficult to discern, but we can see that the Korean is shot. Did the GI escape? The combat scene will be partially replayed near the film’s end, closing the frame the first one opened. The GI will be revealed as Marcus, who is dying from a bayonet thrust.

This isn’t merely a trick. In the 1940s filmmakers realized that some stories, if told chronologically, begin in rather slow and uninvolving fashion. But starting at a crisis late in the story’s causal chain, and then flashing back to what led up to it, can arrest our attention. Think of what The Big Clock (1948) would be like if we started not with the hero dodging around corridors trying to elude the police, but with his mundane office routine earlier that morning. So instead of starting with Greenberg’s funeral, Indignation grabs us with a brief and enigmatic piece of life-or-death action.

1940s frames are more explicit about the framing situation than the combat incident in Indignation. Yet Schamus evidently didn’t want to show Marcus lying there dying and reflecting on his life and leading into the film as a whole: too on-the-nose, and perhaps too obviously fatalistic. The shift to the Jonah Greenberg funeral frees the story action from what Henry James once called “weak specificity.”

There’s also the possibility that Marcus survives; we don’t see him die, even in the finale of the skirmish. The fact that the film can equivocate about whether our narrator is alive or dead emerges as a fresh treatment of the Afterlifer convention.

By raising the possibility of a dead narrator early on, Roth may make us view Marcus’s actions with more detachment, sub specie aeternitatis. The film version, I think, gets us more emotionally invested in Marcus, and this makes the eventual possibility (for me, the likelihood) that he has died more wrenching.

More than Marcus

Even in the enframed 1951 story action, our attachment to Marcus’s range of knowledge isn’t complete. For one thing, there are ellipses—most notably, the crucial scene in which he asks Olivia on their first date. There are also moments in which we run ahead of his awareness. When his mother meets Olivia, Schamus has controlled his actors’ eyelines so that even in a two-shot we’re not looking at the hero but rather at Mrs. Messner, who spots the girl’s wrist scar.

This is sharp visual storytelling. Marcus is unaware of his mother’s observation, but we’re prepared for her later admonition that he’s getting involved with a woman who will bring him misery. (Marcus: “She slit one wrist.” Mrs. M.: “One is enough. We have only two, and one is too much.”)

We’re also a beat ahead of Marcus in one neat shot that shows him stepping onto the quad as he’s facing expulsion. We see his future before he does; the marching ROTC students in the background catch our notice before a rack-focus brings him up to speed.

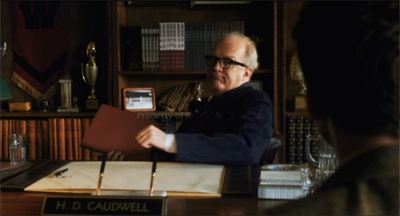

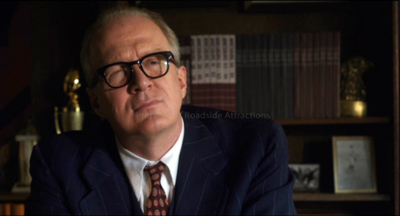

We’re also invited to see parallels that pry us a bit away from Marcus’s immediate experience. At two crucial moments, the adults trying to intimidate him—Dean Caudwell and his mother—come around behind him to keep wheedling.

The know-it-all debater has a chance when fighting face to face, but he crumbles when authority steers from behind.

Above all, our attachment to Marcus is qualified by a second frame, the one that wraps the whole fiction. This is wholly Schamus’s invention—a nested structure of the sort characteristic of 1940s films. At the very beginning and end of Indignation, we see an elderly Olivia in a care facility staring at the wallpaper dotted with a pattern of flowers in a water carafe. The image (also on a skirt she wears in the college portion) harks back to her impromptu bouquet for Marcus in the hospital.

But of course we’re inclined to ask: How likely is it that such a pattern would be used on wallpaper, and would it so neatly coincide with an item in Olivia’s past? We could then ask whether the pattern is in her imagination. (There is a sort of blurring and refocusing on the pattern, suggesting her optical viewpoint.) And since her scenes in the facility bookend the entire film—the Korean War frame, which in turn encloses the Winesburg College days—we might ask whether everything we’ve seen isn’t a product of her fantasy.

I’m not inclined to say that she has made up the whole movie. Indeed, if the wallpaper pattern is her projection, it would have to be so not just in her optical POV but also in the wider shot of her, the first image we get of her as an old woman.

Maybe this room, Caligari-like, is a total projection of her memory? More likely, it’s objectively there but triggers her recollection of Marcus. I’m still uncertain, but it does seem that giving Olivia the ultimate framing for the tale via their shared moment with the flowers suggests that Marcus, who at the end of his last monologue is calling out to her, has somehow finally made contact.

In any event, a purely formal cadence, completing the ABCBA structure and revisiting an ambivalent motif in the film, can balance, in aesthetic terms, the absence of answers to questions posed in the story world. This appeal to geometrical architecture and symmetrical construction is, since Henry James, another novelistic convention: art’s order can frame, if not completely account for, the disorder of life as it’s lived.

Goliath wins

The sequence that has everybody talking is the sixteen-minute two-hander between Marcus and Dean Caudwell. It’s in the book, but Schamus and his players have brought to life the clash between idealism and suave, well-practiced bullying.

Straddling the film’s midpoint, this scene enacts the old proverb. “Old age and treachery trumps youth and skill.” It starts with a simple bureaucratic issue: Marcus’s transfer out of the dorm to a shabby, solitary room. This incident leads Dean Caudwell to charge him with stubbornness, lack of compromise, secrecy about his Jewish identity, friction with his family, intellectual arrogance, and cowardice. The whole cascade is punctuated by the Dean’s intermittent requests to stop calling him “sir.” It’s a verbal boxing match with Marcus gamely fighting on after quite a few low blows. Nobody who read Why I Am Not a Christian in their youth (as I did) can fail to be roused to self-righteous fury by Caudwell’s calm, close-minded innuendo.

Still, in such duels dialogue and performance need to be orchestrated with framing and cutting. Steve McQueen’s solution in Hunger (2008) is the use of a sixteen-minute profile long-shot, followed by a cut in to Bobby Sands’ hand picking up his cigarettes, and then a very tight close-up of his face as he continues speaking.

The interruption of the long take gives special prominence to a shift in the conversation, when Sands recalls his childhood. Later shots revert to shorter shot/ reverse-shot exchanges.

So framing and cutting can articulate phases of the drama. This Schamus does very carefully in the Indignation scene. To abbreviate:

Phase 1: More or less businesslike and polite: Why couldn’t Marcus compromise with his roommate? 180-degree cuts, with framing favoring Dean Caudwell–centered and dominating Marcus.

Phase 2: Caudwell gets personal. Why didn’t Marcus identify his father as a kosher butcher? Eventually he’ll accuse Marcus of intolerance. Here a fairly lengthy profile shot reminiscent of Hunger gives way to shot/ reverse-shot.

Phase 3: More personal probing: How does Marcus get along with his family? What about his sex life? And religion? After more shot/reverse shot, Marcus, sweating and feeling sick, rises to defend himself in close-up. That calls forth the closest shot yet of Caudwell.

Phase 5: Caudwell says Marcus’ sophistry will make him a fine lawyer. He comes to stand behind Marcus, putting his hands on his shoulders. Then he sits beside him, to drill in still more. Marcus, shaky, asks to leave.

Phase 6: At the door: Marcus is feeling sick. The dean asks if he’d like to play baseball. Finally Markus collapses and starts vomiting.

Schamus has saved shot/ reverse shot for when the scene heats up, and saved his close-ups for when things reach a pitch. This reminds us, as the Hunger scene does, that if you’re going to use a standard technique, hold off until it will do the most good. Ditto for the low angle on Marcus throwing up; that comes with more force if we haven’t already had low angles before. Schamus has let his cutting and shot scales amp up the drama without the crushing emphasis supplied by so many directors. Yes, I’m thinking of the barrage of close-ups in every dialogue scene of Jason Bourne. (Thanks to Paul Greengrass, Tommy Lee Jones’s facial contours qualify for Federal Drought Relief funds.)

I think that Indignation will be studied for years as an intelligent adaptation of Roth’s novel, but it ought also to be admired as a well-crafted work in its own right. It finds fresh ways of molding fiction techniques to the demands of cinema in general and Hollywood tradition in particular. And the film reminds us—or me, at least—how much contemporary filmmaking owes to the consolidation of “novelistic cinema” seventy years ago.

Thanks to James Schamus, Gustavo Rosa, and Lauren Hynnek for information and assistance, . For more on James’s career, see our entry.

Students of literature might find another novelistic analogy in Olivia’s explanation of her suicide attempt. It somewhat resembles the technique of free indirect discourse, when the third-person authorial voice adopts the language and syntax of the character’s thought. Roth employs this in the third-person tailpiece of his novel. Instead of “If only I hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for me at chapel!” we get “If only he hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for him at chapel!” Is it possible to have a cinematic equivalent: an objective vision that is pervaded by the character’s state of mind? Pasolini thought so, and suggested Red Desert, Before the Revolution, and Godard’s films as examples of it. Perhaps this flashback sequence counts as a case of Pasolini’s “free indirect subjective.”

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I briefly discuss the resurgence of 1940s storytelling strategies in recent studio cinema (pp. 72, 83). A general discussion of my interest in 1940s narrative is here. Elsewhere I make the case for Tarantino reviving 40s formats; for the importance of Afterlifers in the Forties; for nested narratives like that of Indignation; for replays that provide new information; and for the blurring of subjective and objective in Nightmare Alley.

For more on novelistic strategies in film, see “Watching a movie, page by page” and Kristin’s entries on the Hobbit films, all linked here.

Indignation.