Oof! Out!

Tuesday | September 6, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

I Remember Mama (1948).

DB here:

Jim Naremore calls 1940s American studio cinema “the beating heart of Hollywood.” I think he’s right. For about five years I’ve been working on a book taking EKGs of that beating heart. The book tries to understand some factors that made Forties Hollywood so dynamic and continually captivating.

Doing this called my attention to so many things: the fresh subject matter, the variations in genres, the stylistic experiments, the superb performances, the quality of line-by-line writing. But I focused on something that’s still pretty big: new, or newly revived, storytelling methods. Those methods made that period exciting–not just in film noir, where we tend to think that narrative got pretty wild, but also in melodramas, rom-coms, musicals, and the rest.

It’s the only study I know of how narrative techniques emerged and developed in a single era. No wonder it took five years. I watched over 600 films. I trawled through books and trade papers for hints about what the producers, directors, and writers thought they were doing. And because a lot of techniques weren’t unique to film (e.g., flashbacks, first-person voice-over, etc.), I wound up reading forgotten plays and neglected novels, while listening to hours of old-time radio.

The project started when I was asked to do a series of lectures, “Dark Passages,” for Belgium’s Summer Film College in 2011. Just before that, I tried out some ideas in some spring blog entries. Things crystallized in 2013, when I firmed the project up. In this entry, I promised, falsely, that the book would be short.

Since then, I’ve been immersed in fun, except for the Red Skelton movies. I loved having Mercury Theatre playing in my car during drive-time, and digging out 1930s and 1940s books from the oldest section of our university library.

I think the book says some new things about films of the period, and about the development of American popular entertainment more generally. For one thing, I think I have a better understanding of how High Modernist techniques (out of Joyce, Woolf, etc.) made their way into mass art. (Not directly, I’m convinced.) For another, I have a new respect for those filmmakers who tried something daring, even if–see my last post on The Chase (1946)–they somewhat botched it. And it develops some ideas I floated in The Way Hollywood Tells It: ideas about how modern filmmakers like Tarantino and Nolan are continuing a Forties tradition of somewhat experimental narrative.

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling went off to the publisher this afternoon. Said publisher is the University of Chicago Press, who did a fine job with our Minding Movies and my recent little book The Rhapsodes, to which this is sort of a bigger, thuggier brother.

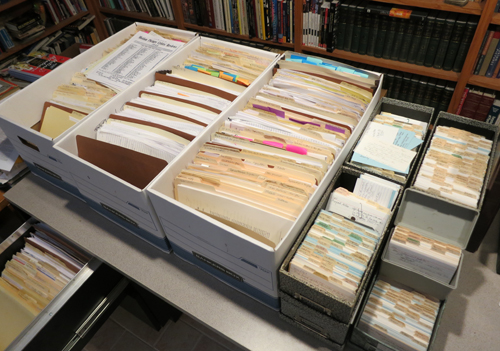

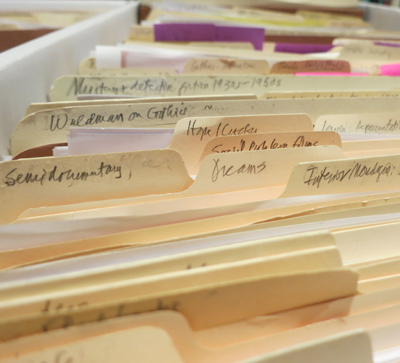

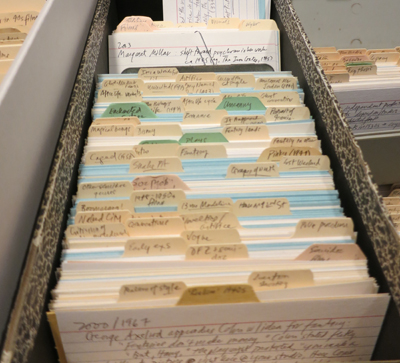

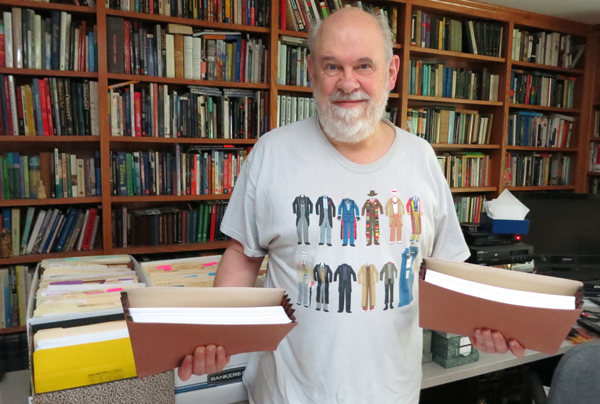

In the meantime, just to give you an idea of how one writer makes a book, I append some images from the workbench, before I pack up the paperwork. Here are the file folders and note cards I worked from. Hard to get those long note-card boxes nowadays; I needed 8 1/2 for this project.

Yes, I’m still a pen-and-paper nerd. All that’s changed since my 60s student years is the worsening of my handwriting.

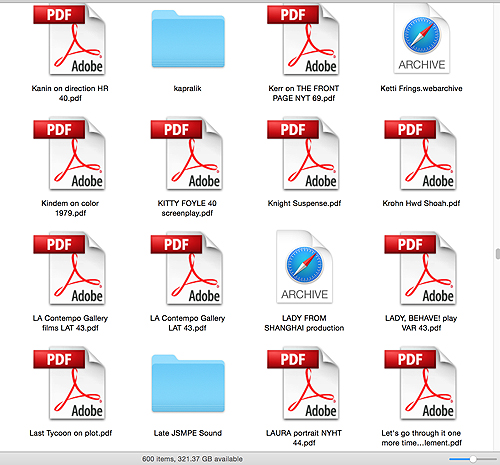

Like you, I have hundreds of digital files too.

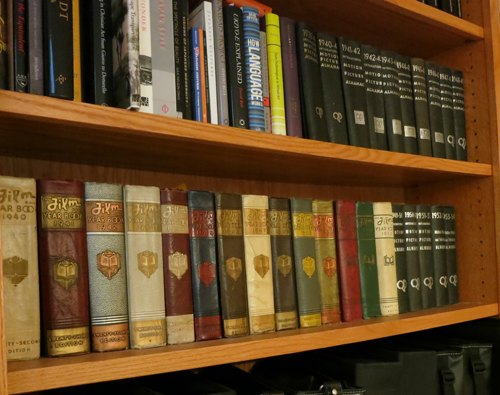

I was reliant on my old friends, The Motion Picture Almanac and The Film Daily Yearbook.

I amassed many albums of DVDs, as you’d expect–thanks chiefly to Turner Classic Movies.

Of course there are scores of books about films and figures of the period. I depended a lot on two key surveys: Douglas Gomery’s Hollywood Studio System (both editions) and Tom Schatz’s Boom and Bust: American Cinema of the 1940s. I didn’t rely much on all those books of a reflectionist, Zeitgeisty flavor–for reasons I’ve indicated here as well as in the book.

Reinventing Hollywood should be out this time next year. It should run to around 550 pages, with 180 illustrations. In addition, I’ll be putting up a dozen or so clips online to supplement some of my analyses. Hereabouts, from time to time I’ll preview arguments in the book.

I want to thank my editor, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues at the University of Chicago for supporting the book. I also owe a debt to Jim Naremore, Jeff Smith, and Malcolm Turvey for their close reading of the thing in draft form, and of course to Kristin for help in matters big and small. The couple dozen of friends and colleagues who helped me, too many to list here, are gratefully acknowledged in the text.

To give you a sense of what the book is up to, I’ve gathered most of my Forties blog entries into a separate category. Some of these are grist for the book, and some, like the ones on The Magnificent Ambersons and on The Chase, expand the book’s analysis.

In all it reminds me of what the Duke of Gloucester said to Gibbon: ““Another damn’d thick, square book! Always, scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh! Mr. Gibbon?” I’ve used this before, but after writing or rewriting seven books since I retired in 2004, it seems even more grimly appropriate. The reader is warned.

Photo by Kristin Thompson.