Archive for October 2016

Eep, omigosh, urk, smerp, and other Archie epithets

DB here:

Not all cinephiles are comics fans, but quite a few are. I guess it’s partly a matter of the Adolescent Window, and partly an intuition that both are forms of what Will Eisner calls “sequential art.”

For my part, a Boomer childhood spent with Nancy and Little Lulu and Scrooge McDuck was followed by a boyhood fastened on Superman and Batman. Then came the cutoff. I went to college as the Marvel Universe was populating, and I never got into Underground Comix. Only Krazy Kat stayed with me through my college years.

In the 80s Kristin and I followed young talents like Matt Groening, Berke Breathed, and Lynda Barry, while becoming fans of McCay. When I encountered Eurocomics, particularly the Clear Line style and its heirs, I perked up. Joost Swarte (and here) was a special favorite of ours. At about the same time I revisited the old stuff, like Cliff Sterritt. During the 90s and 00s, I tracked the emergence of Ware, Clowes, and other independents.

In the 80s Kristin and I followed young talents like Matt Groening, Berke Breathed, and Lynda Barry, while becoming fans of McCay. When I encountered Eurocomics, particularly the Clear Line style and its heirs, I perked up. Joost Swarte (and here) was a special favorite of ours. At about the same time I revisited the old stuff, like Cliff Sterritt. During the 90s and 00s, I tracked the emergence of Ware, Clowes, and other independents.

Somewhere in all this, Archie abides. I can’t remember when I started reading him, or when I stopped, but he was for me, as for many others, simply and permanently there. Only when I accidentally learned in 2009 that he was to marry Veronica did I go back to him. Finding an interesting variant of the three-roads motif of folklore, I whipped up a blog entry. I added some thoughts about the skillful graphic design of Bob Montana’s 40s work, but in the process I was too dismissive of the later decades chronicling life at Riverdale High.

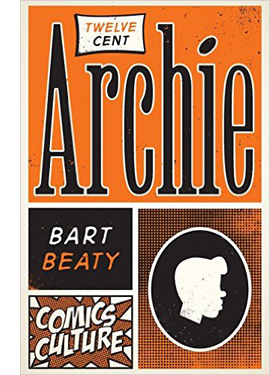

I realize my error now thanks to Bart Beaty’s wonderful Twelve Cent Archie. It’s a critical and historical study of Archie’s world from December 1961 to July 1969, a period when the comics sold for a princely $.12. That’s also the period, Beaty maintains, when the books’ most skilful writers and artists were at work: Stan Lucey (the Archie titles), Dan DeCarlo (Betty and Veronica), and Samm Schwartz (Jughead). Beaty read every book in the nineteen series, over 900 volumes in all. This admirable undertaking yields funny and enlightening results. It’s one of the best books of comics criticism I’ve ever read.

The Archie Machine

For many of us, Archie is surpassed only by Nancy in the Bland Storytelling Sweepstakes. Archie is a freckle-faced guy on the make, rich girl Veronica alternately two-times him and flies into jealous rages, and Betty pines for Arch from afar. Archie’s rival Reggie tries to gum everything up, while Jughead watches with a mix of scorn and indifference. The plots are filled with deception, misunderstandings, horrible coincidences, and slapstick. Needless to say, the adults—teacher Miss Grundy, principal Mr. Weatherbee, Coach Kleats, Archie’s parents, Veronica’s dad Mr. Lodge—don’t have a clue.

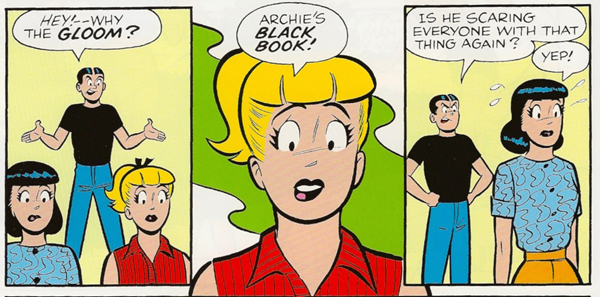

The saga is so cut-and-dried that the makers could publish a story called “How to Write Comics” (1965), in which the moves are laid out with daunting clarity.

These tips remain good advice for plot-making. Had Beaty done no more than unearth this tale, we’d owe him a lot. As ever in popular culture, though, things aren’t so simple. Beaty shows us why.

At one level he embraces the sheer repetitiveness of it all—what he calls the Archie Machine. Oddly, as he points out, Arch is, narratively speaking, null. He can be a good student or a poor one, a clever manipulator or a klutz. Only a few traits, such as his need for money and his innocent lust for vertiginous kisses, persist. Reacting to situations rather than creating them, neither hero nor antihero, he’s more of an unhero, “a blank space on which stories are written.” As a result, there’s little continuity in the stories. If the plot demands Archie to be good in French, he will be, even if previous stories have shown him to be linguistically inept. Besides, as Beaty asks, “Does Riverdale High even have a French teacher?”

The same goes for Riverdale, which despite its name, seems serenely indifferent to its river, which hardly ever appears. There are four seasons, but the topography is fluid, provided with mountains, beaches, forests, and farm fields as needed. This Borgesian landscape reminds you of the Simpsons’ Springfield, but that municipality has landmarks for ready reckoning. Homer always lives next door to Ned, Moe’s bar is always beside King Toot’s Music Store. Beaty points out that in Riverdale, we can’t say whether Veronica’s house is on Archie’s way to school: sometimes it is, sometimes not. “It depends on the needs of the story.” And unlike Springfield, Riverdale is forbiddingly WASP: “a wish-dream of white privilege and normative sexualities.”

Given this mixture of relentless monotony and casual vagueness, the challenge for the writers and artists was to make something interesting. Here’s where Beaty’s book pulls me in: Artists need to solve problems. He shows that his three main artisans created fun and cleverness out of nearly nothing.

I dimly remember thinking, as a kid, that there was more going on in those books than I could understand, but finally, sixty years later, I get a glimpse of it.

Take Betty. Betty isn’t just the lovelorn also-ran. She plots against “best friend” Veronica, pulls pranks to fool the hapless Arch, and generally acts, as Beaty notes, like a stalker. As for Veronica, she can be quite the schemer too. Pictorially, though, they might be twin sisters. “Betty = Veronica,” one of Beaty’s 100 (!) chapters, asks: “Why does Archie struggle to choose between Betty and Veronica when, for all intents and purposes, they are exactly the same person?” Okay, Betty has a ponytail (to which Beaty devotes another chapter), but you take his point. Even when the girls decide to change hairstyles, they wind up looking cloned.

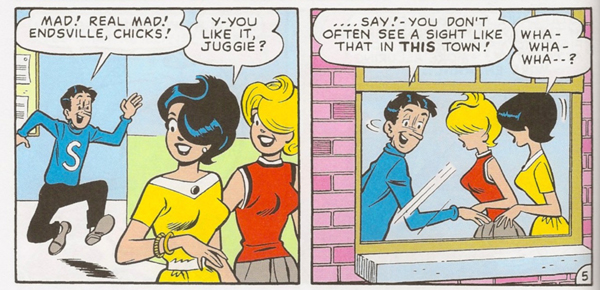

In scenes like this, you have to believe that the creators were having fun with the standard-issue look of our two heroines. Their cookie-cutter similarity allows for ingenious changes in posture, costume, and expression (see below), and can be a source of gags, as here–when their peekaboo hair styles keep them from seeing a pop star’s passing below them.

Silly dialogue that made me snicker still does. Reggie strolls along singing, “I love me, I think I’m grand. When I’m with me I hold my hand.” In the summer I graduated from high school, I don’t think I read the following exchange, but I would have mostly understood it.

Archie, at Betty’s door: “Howdy! I’m a mild mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper!”

Betty: “Come in, mild-mannered reporter! Do something super!”

Archie: “I’ll try!” (Kisses Betty off her feet)

Betty (staggered): “Whew! That’s what I call SUPER, man!”

Betty (recovered, ushering Archie to the door): “Let’s go! I’m not a good first violinist, but I can play second fiddle with the best!”

Archie (serious): “You wound me!”

You wound me?! Denying he’s grabbing Betty on the rebound is an act of supreme callousness. No Superman, Arch. Beaty credits some of the best lines to writer Frank Doyle, source of “I never snapped a whipper in my life.” I wonder if Doyle wrote the oft-reprinted Tiger (1961) with its memorable “A boiling, bubbling volcano flames behind this mild-mannered facade.”

Fun lovin’

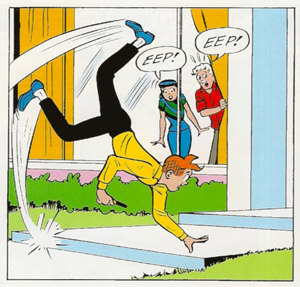

Beaty offers so many ideas and observations that I can pause only on the major thing he convinced me of: the fine comic draftsmanship of Harry Lucey. Beaty waxes eloquent on Mr. Lodge’s anatomical twists and turns across a single page. That called my attention to the fact that Lucey drew funny, especially in scenes of manic action. It’s all in the legs and toes, kids.

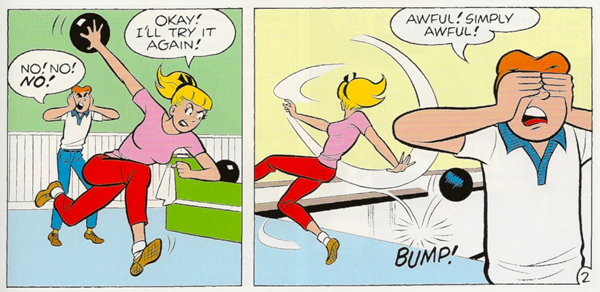

Who expects contrapposto in an Archie comic? But we get it when Betty goes bowling.

At times we get the classic comic multiple-image stuff that not only cartoonists but animators like Disney and Bob Clampett used in movies. Archie has been spotted carrying his mother’s purse.

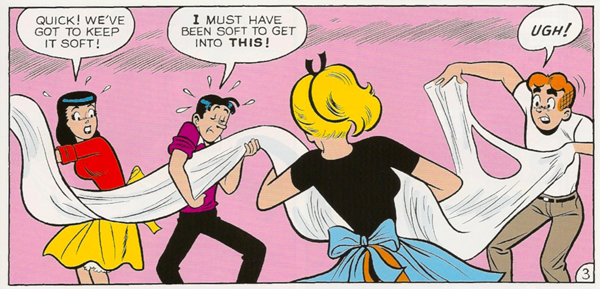

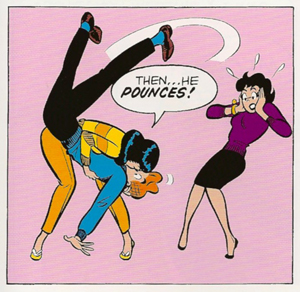

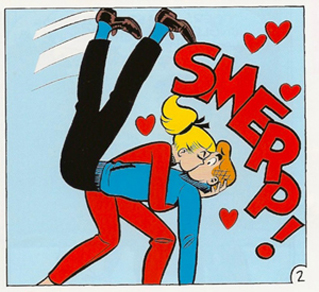

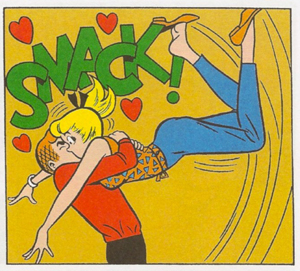

As Beaty shows, Lucey excelled at calisthenic clinches and tornado-intensity smooches. When a character, even a dog, kisses another character, he/she/it sweeps the kissee off his/her feet, literally.

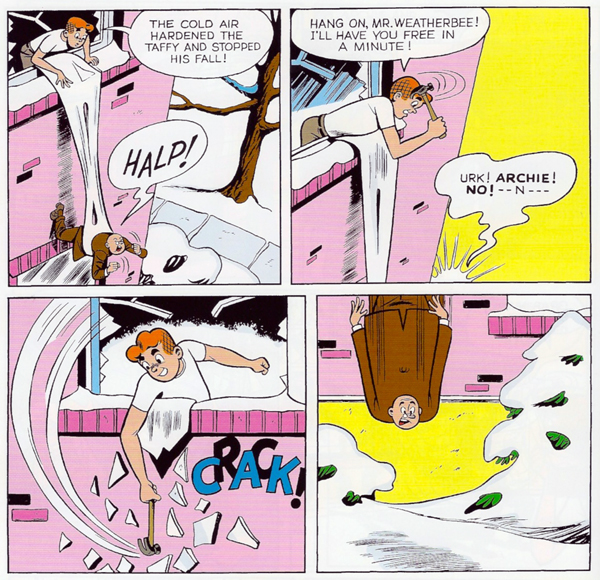

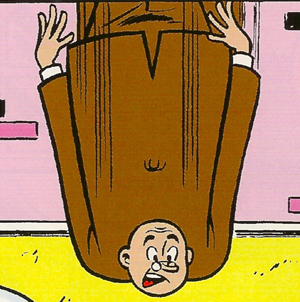

Perhaps because the action is often so violent, Lucey can spare a panel that’s a virtual freeze-frame. Any other artist would have wrapped Mr. Weatherbee, plummeting out of his taffy shroud, in a flurry of speed lines, as above. The near-absence of those lines makes the poor man seem suspended forever before his fall.

Actually there are speed lines, but they’re so slight and striated they might be creases in the brown suit. Only the sharpest eye will catch the ones around Mr. Weatherbee’s left wrist.

Thanks to Lucey’s technique, in the same panel the hapless Riverdale principal both falls and hangs suspended.

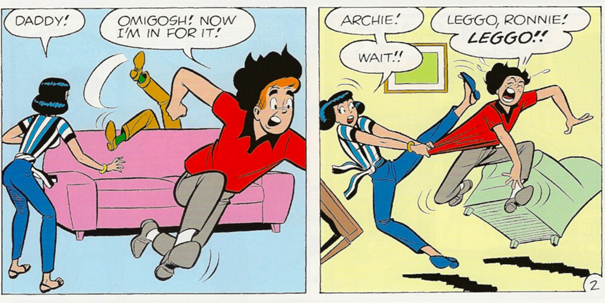

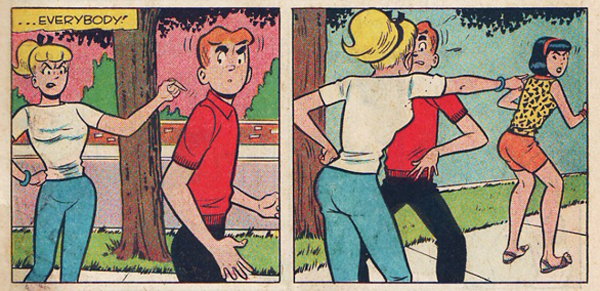

Hergé likeds to keep his scene’s space clear and consistent, modifying it slightly with “cut-ins” and “pans.” Lucey, like other American comics artists, freely changes angle and even character arrangement to create variety and to point up dialogue. In one pair of panels, the change of angle is bold, slicing off half of Archie’s face to give greater emphasis to Betty’s angry arm-thrust and Ronnie’s reaction on the far right.

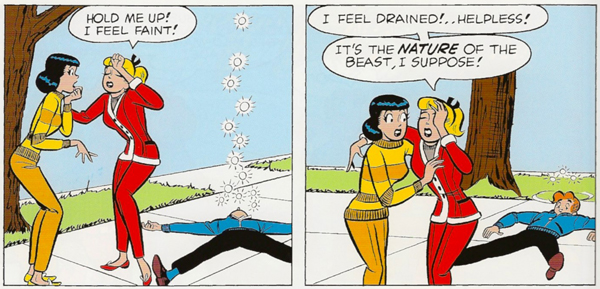

A slight change of angle can accentuate background action–below, a flattened Archie raising his head. But Ronnie and Betty have already slid toward the foreground as well.

Characters are freely shifted around the frame, usually in obedience to a left-to-right reading of the balloons. But across a page these spatial reorientations can create a vivacious pattern. Against the mild purple chair, for example, Betty’s scandalous polka-dot dress pops out in each panel while dominating the layout as a whole.

Lucey could do detail too. In any given panel or set of panels, there are little touches that distinguish Betty from Veronica—typically, the lips. Here Betty’s mouth in the second panel seems to catch Veronica’s sideways twist in the first. By the third, Veronica’s mouth has straightened out a little.

Like Archie comics or despise them, but don’t talk about Cathy or Dilbert in the same breath. If you’re a cartoonist, you should be able to draw. If you can infuse your drawing with vivacity, so much the better.

I’ve followed Beaty’s work since his magisterial series, “Eurocomics for Beginners” ran in The Comics Journal in the 1990s. His many books are major contributions to comics scholarship. For sheer pleasure, though, nothing of his I’ve read surpasses Twelve-Cent Archie. It’s at once personal–he recalls his childhood encounter with a cache of Archie books on summer vacation–and analytical in a sympathetic way. Like a lot of good criticism, it opens your eyes while making you smile.

Bart Beaty provides background on Twelve Cent Archie in this interview. A worthwhile review is in The Atlantic Monthly. Beaty talks with indefatigable media analyst and blogger Henry Jenkins at Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell of 20th Century Books and Bruce Ayers of Capital City Comics for help in finding some Archie stories. Thanks as well to Jim Danky for many long lunches about comics, film, and less important things.

The Archie-marries-Veronica issue I wrote about in 2009 was but the beginning of a long parallel-universe cycle. For a list of the many other revisions in the Archie-verse, see this article. Then there are the Betty and Veronica reboots. The horror cycle, Afterlife with Archie, went in another direction. (And you thought the original kids were zombified.) It’s been a big success. Urk!

In timely fashion, Mad City Movie Guy Gerald Peary has come out with his own contribution, a documentary called Archie’s Betty. He too has reviewed Beaty’s book for The Arts Fuse.

P. S. 23 January 2017: Here’s some fascinating backstory on the “reimagining” or “rebooting” or “reinvention” of the Archie saga. Turns out Forking-Path Archie, which got my attention, was a turning point for the company as well as its protagonist.

Dragons, tigers, and two programmers

Yellowing (Chan Tze Woon, 2016).

DB here:

It was Asian film that brought me to the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2006, when Tony Rayns asked me to serve on the Dragons and Tigers awards jury. Ever since, Kristin and I have been returning; Tony made VIFF North America’s prime venue for cutting-edge Asian film. Name a major director from the region, and you’ll find that Tony scouted his or her early work for Vancouver.

For some years now, Tony’s co-programmer has been Chinese cinema expert Shelly Kraicer, who has been no less energetic in seeking out exciting new films. You can survey their track record by scanning our VIFF blog entries across the years.

Out of the many films in this year’s D & T retrospective, here are five that I especially admire.

Genres redux

Godspeed.

Across his career, Kore-eda Hirokazu has been a genre pluralist, but in recent years he seems to have settled into the shomin-geki, the bittersweet tale of lower-middle-class life. On the heels of Our Little Sister comes another family dramedy, After the Storm.

Once a prize-winning novelist, Ryota (the lanky, lantern-jawed Abe Hiroshi) is now a racetrack addict and a cheap detective not averse to shaking down high-school kids. After his father dies, and under the jaundiced eyes of his mother, he makes feeble efforts to reunite with his divorced wife and his baseball-playing son.

As usual with Kore-eda, everything flows in simple, unforced fashion, with every shot trimly composed and expertly timed. The emphasis falls on the actors, particularly as they’re captured in mundane activities. Ryota’s mother and sister are first seen writing thank-you notes to people who came to the funeral; he swills in fast food and throws away money on lottery tickets.

Ryota is one of Kore-eda’s most objectionable protagonists. He uses his admittedly minimal surveillance skills to spy on his wife, and he tries to swipe a family scroll to pawn. In an American film, this unlikable loser would pass through an arc that makes him caring, sharing, and on the road to rehab. Instead, as in many Japanese films, the unhappy character relapses into childhood—here, curling up with his son inside a playground octopus during a typhoon. It’s his effort to mimic a bonding moment with his father, but does it succeed now? Kore-eda isn’t betting on it.

Altogether less tranquil is Godspeed, from the Taiwanese director Chung Mong-hung. Chung has given us the horror film Soul (2013), the well-received Fourth Portrait (2010), and the lively Parking (2008), which I reviewed at an earlier VIFF session.

Godspeed is a Tarantinoish excursion into the underworld. It alternates violent scenes of betrayal and reprisals with comic interludes involving a drug courier and the taxi driver he’s hired to carry him to meet the bosses. The film is made with great panache, but for me what makes it noteworthy is that the driver is played by the great Michael Hui, dean of sour Hong Kong social satire.

Hui made his name as a television star before switching to films like The Private Eyes (1976), Security Unlimited (1981), and our favorite, Chicken and Duck Talk (1988). Godspeed revives Hui’s comic persona, the tight-fisted, corner-cutting bargainer who isn’t as clever as he thinks. As Old Xu, he reminisces about Hong Kong traffic and marital woes while trying to wangle a high fare from the phlegmatic, not overbright drug mule. Their misadventures—stumbling into a funeral, being stuffed into a car boot—serve as a counterpoint to the drug war escalating around them. No masterpiece, Godspeed is a beguiling exercise and a welcome return to a legendary and apparently ageless figure of Chinese cinema.

Mysterious, and fun

Another year, another stroll through Hong Sangsoo’s garden of forking paths.

With compositions that are about as banal as they can be, the films don’t aim to dazzle us pictorially. (Nice lighting, though.) The basics are really basic: Straight-on angles, fixed long take two-shots, simple come-and-go pans, an occasional and inexplicable zoom. These are his tools.

Dialogue and performance drive the action, which consists mostly of chance encounters and conversations in cafés, bars, restaurants, and bedrooms. His characters are students, artists, and film directors (usually fairly pretentious ones). Romantic hookups emerge, only to dissolve or play themselves out in parallel worlds, the whole presented in a “stacked” arrangement of modular scenes.

These scenic blocks display an obsessive, almost never mechanical, recourse to split viewpoints, recursive time schemes, mirror inversions, and whimsically varied replays. I’ve argued earlier that these permutations often test our faulty memory for exactly what transpired in a scene many minutes before, but it should be noted that sometimes, as in the last stretch of Oki’s Movie (2010), he’ll set the variations side by side.

Or maybe just side by side in your head. If the auteur theory didn’t exist, it would have to be invented to account for the effect of Yourself and Yours. In any other movie, when a man recognizes a young woman in a café, and she says he’s mistaken her for her twin, we might be inclined to take it as a brush-off. In a Hong movie, the scene makes us think back through all his other plots that have relied on doubling. So maybe this time he’s found a new variation? Has he got an actual pair of twins who will circulate through the scenes, constantly being taken for one another?

Suffice it to say that the young woman (women?), repeatedly encountering three men who are attracted to her (them?), becomes (become?) the pretext for the usual Hong mockery of male vanity and insecurity. The lackadaisical painter Youngsoo is worried about his girlfriend Minjung, who drinks more than he’d like. Moreover, his friend reports that she’s been seen with other men. Quickly enough, we spot her sharing drinks with an older man and a film director—who discover that they are old classmates. “This is mysterious,” the director remarks, “and fun.” None of the would-be Romeos notice that the lady in question is reading Kafka’s The Metamorphosis.

Hong always has another card up his sleeve, and Yourself and Yours, while not as ingenious as his previous entry Right Now, Wrong Then (2015), is satisfyingly teasing. It also yields one of the most flagrantly self-indulgent trailers I know: faithful to the movie, but frustrating in just the right ways.

Taking it to the streets

When college students en masse join a movement for social change, their positions tend to be vindicated in the long run. In the United States, students were right to support movements against nuclear proliferation, against racial discrimination, against American involvement in Vietnam, for women’s liberation and LGBT rights, against the invasion of Iraq, and, right here in Wisconsin, against Republican union-busting and voter suppression. The same pattern can be observed around the world, in student protests in Europe, South America, and Asia. Elders deride students as naïve, but more often than not, student activists critical of the status quo get principled politics right.

Why? I suspect several causes, including the fact that many (not all) students are reading, thinking, and learning while the general populace trudges through the dull compulsion of everyday labor. College flings together students from many backgrounds and may open eyes about how other people live. (Right-wingers worry too much about liberal professors indoctrinating students. In my experience, students are more influenced by their peers than by the likes of me.) And of course the flexible scheduling of college days allows motivated students the time to engage in political action.

Whatever the causes, it’s no surprise that in Hong Kong, the street protests running from September through December of 2014 were launched by young people. In August the mainland’s Communist Party decreed that instead of direct election of the territory’s Chief Executive, candidates would be chosen by a nominating committee comprised of businessmen and politicians sympathetic to Beijing. In effect, this guaranteed a puppet leader of the type all too familiar in the territory. Students responded by organizing actions similar to the Occupy movement in America. With surprising speed, civil disobedience and sit-down occupation spread through downtown areas of Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula.

Hong Kongers were long considered indifferent to politics, only concerned with scrambling to get ahead and make money. But the world had to notice when tens of thousands of students and ordinary men and women built vast encampments in the streets in front of chic shops and noodle restaurants. Wearing yellow ribbons and hard-hats, and armed with umbrellas to protect them against sun, rain, and tear gas, they were apparently ready for a long stay.

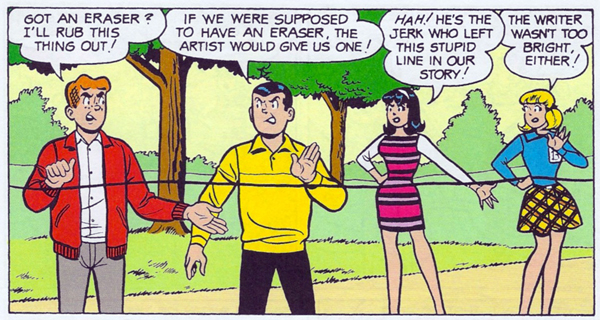

This epochal event in Hong Kong history is documented in Yellowing, a new film by Chan Tse Woon. It was made under the auspices of Ying e chi, a filmmaking collective that has been working since the propitious year 1997, when the British turned the territory over to the People’s Republic. Although framed as a diary, it’s basically a cinéma vérité account of moments and vignettes of the Umbrella Revolution. The voice-over narration is keenly personal, beginning with home-movie footage of Chan’s childhood and youth, interrupted by his memory of repeated promises that democracy would soon arrive.

Loosely organized, Yellowing offers no systematic chronology of events à la a PBS program. It’s defiantly local, a snapshot album for Hong Kongers who will recognize each phase of the movement. At the start, some gorgeous nighttime cityscapes are shattered by confrontations with police (“Police, retreat,” the students chant) and conversations with student organizers in their down time. In the two hours that follow, we spend a lot of that time with young people like the ceaselessly beaming Rachel, who’s now considering becoming a civil rights lawyer. We see one boy passing out wristbands reading, They can’t kill us all.

Students set up tents, squat in pounding rain, organize English classes, and run supply chains across the vast areas of occupation. There are clashes with police and civilians. (“Your flesh and blood belongs to your family,” a man charges.) Chan’s camera captures, helter-skelter, assaults from cops and street gangs. There are camera duels, with police filming demonstrators while demonstrators film police. Chan’s voice-over says that he thought his camera would protect him, but he still gets punched in the face. The occupiers practice tactical evasion and passive resistance, but there’s no effort to heroicize them. Many are crying as police lead them away.

Despite the almost casual presentation, you realize how much these kids are risking. Many are poor, some are trying to hang onto a job, and nearly all realize that this will change their lives. “Even if we lose this fight, we’ll lose together.” As for the angry citizens wearing blue ribbons declaring support for authorities, the students are sympathetic: “Don’t you think they need democracy too?”

The film circles back to the opening, with Daddy-cam shots of children. We hear Rachel writing in reply to a professor who had urged the students to give way for the sake of “security,” and to stop being tools of “foreign subversion.” The film lingers on her cheerful, polite suggestion that Mainland domination has replaced British colonialism, and that the children of the future deserve better.

Most of our politicians and all of our plutocrats will never know the sort of courage that these young people displayed with modest, good-humored tenacity. Unarmed—unlike the Y’all Queda fraidycats who occupied our Oregon wildlife refuge—these unprepossessing kids stood a very good chance of being brutalized by a government not known for recognizing the niceties of due process. You feel proud of the young people of Hong Kong while watching this heartbreaking, hopeful film. As often happens, the students were both righteous and right.

Not hope, fear

Ying e chi has often worked with theatres to show independent films, but Yellowing has been denied a theatrical release. Instead, Variety reports, producer Vincent Chui has arranged for guerrilla screenings. Five ticketed shows were held at the Hong Kong Film Archive, in order to qualify for this year’s Hong Kong Film Awards.

The resistance to Yellowing doubtless owes a lot to the controversy surrounding another film, Ten Years (2015). It won astonishing success in local theatres. According to Maggie Lee in Variety, it cost only US$65,000 but earned nearly $800,000 before Beijing realized how subversive it was and blasted it as a “thought virus.” Ten Years was nominated for a Hong Kong Film Award, which made the PRC cancel television coverage of the ceremony. When the film won the Best Picture prize, shock waves went through the film community, and it was denounced by producers and executives. It was soon cast out of theatres, but screenings continued in community centers, churches, and outdoor venues. It’s slated for a DVD release soon.

Ten Years consists of five shorts linked by the premise of local life in 2025. In its dystopian portrayal of Mainland domination of Hong Kong, it’s a fairly direct outgrowth of the Umbrella Revolution. But if Yellowing documents the movement’s hope, this film exposes, as many commentators have noted, fear.

One episode, “Extras,” dramatizes behind-the-scenes scenes political machinations as a sort of noir comedy. Two hapless thugs are hired to stage an assassination attempt that will arouse public support for a new security law. While the men rehearse their gun choreography, the puppeteers debate whether killing or wounding the targets would play better in the media.

Other episodes are more concerned with the cultural impact of Beijing’s dominance of local life. “Season of the End” presents scientists searching rubble for signs of now-vanished Hong Kong life, shot in ominously clinical detail. “Dialect” presumes that Mandarin is becoming the official language of the territory, and we see a taxi driver struggling to cast off his Cantonese. “Local Egg” also centers on language. Here a shopkeeper is forbidden to use the word “local” because it suggests those political factions struggling to keep Hong Kong distinct, or maybe pushing it to become independent. In an echo of the Cultural Revolution, this episode shows schoolkids in uniform arriving with iPads to check shops’ compliance with the list of forbidden words and retail items.

The most emotionally wrenching episode, “Self-Immolator,” is a pseudo-documentary. Startling scorch-marks on the sidewalk are the traces of someone who burned to death in protest of government oppression. Through talking heads, a collage of demonstration footage, and some investigation, the film traces how a young man’s hunger strike led to the mysterious self-immolation. Several candidates for the self-sacrifice are canvassed before, in a break with the documentary frame, the protest suicide is shown. In the conclusion, an umbrella is seen aflame, perhaps forming a requiem for the 2014 protests.

Ten Years is a good example of how a film can have social importance because of the moment at which it emerges. Along with Yellowing, it will be a lasting memorial to the struggles of Hong Kong people to introduce democracy to China.

Thanks to Tony and Shelly for all their work in setting up these screenings. In addition, Kristin and I are grateful to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and Jennie Lee Craig and their colleagues for making our VIFF visit so enjoyable and enlightening. Special thanks to Tallulah for cheerfulness and Lillooet for the waffles.

Thanks to our regular attendance at VIFF, we’ve discussed many of Hong Sangsoo’s films; see the director category.

The development of the Umbrella Revolution is traced in this long New York Times story. Last August, accused student leaders got surprisingly light sentences. Some of the “localists” and Occupiers won places in the Legco elections and are expected to make waves.

Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer.

More from VIFF 2016

The Death of Louis XIV (Albert Serra, 2016).

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended yesterday, but the films and the pleasures they yielded linger on. Our first two entries are by Kristin, the last two by David.

Smog over Tehran

Iranian film and television director Behnam Behzadi is not well-known outside his native country. Inversion, which was shown in the Un Certain Regard section of Cannes this year, suggests that he deserves to have more international exposure for his work.

The title refers to the meteorological phenomenon that can cause dense pollution to form at ground level. The film opens with shots of Tehran streets seen dimly through a thick haze. The pollution has a causal role to play, since the heroine’s elderly mother ends up in a hospital as a result of breathing problems. More metaphorically, however, the title refers to a sudden reversal in Niloofar’s situation.

Initially she seems to be in a relatively strong position for a Iranian woman. Still unmarried in her 30s, she runs a small, prosperous garments factory and begins to date an amiable man whom she clearly likes. Her mother’s sudden health crisis, however, leads a doctor to insist that she be moved to the healthier northern part of the country, where Niloofar’s sister and brother-in-law happen to own a small villa. Niloofar, with no spouse or children, is pushed by the couple and her brother into agreeing to go along and take care of her mother. She hopes to keep the factory going, but the brother selfishly rents out the premises to pay off his own debts. Niloofar resists going with her mother, but as her siblings ignore her wishes and she discovers that the man she may be considering marrying has kept an unpleasant secret from her, she realizes how little power she has over her own life.

As in Farhadi’s films, a seemingly ordinary situation suddenly deteriorates from a simple cause. But Farhadi tends to gain complexity by avoiding making his characters into villains. In his films, as in Renoir’s, “everyone has his reasons.” In Inversion, however, the brother is straightforwardly in the wrong, refusing to consider Niloofar’s desires and even threatening her with violence during one argument. Overall the film is entertaining, with Niloofar an engaging figure who gives an insight into the situation of women in contemporary Iran.

Mistakes were made

Asghar Farhadi is best known for A Separation (2011), the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film. His earlier masterpieces, About Elly (2009) and my own favorite, Fireworks Wednesday (2006), are slowly coming to be known in the West, largely via home video. After the slightly disappointing The Past (2013), Farhadi is back on track with The Salesman.

The film opens with a tense, dramatic scene in which a Tehran apartment building threatens to collapse and its inhabitants frantically struggle to evacuate. The result is that the central characters, Emad and his wife Rana, must quickly find a temporary apartment (see bottom) while they also prepare to star in a production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

They seem to be coping until Rana mistakenly opens the door of their new apartment, assuming that her husband has come home. The shot holds on the door, standing ajar, as Rana moves off to take a shower and the scene ends. Later we learn that an unknown assailant has entered the apartment. Whether he raped Rana or simply startled her so that she fell and cut herself on broken glass is never revealed, but she is traumatized and unable to proceed, either with her everyday life or her role as Linda Loman in the play. Emad tries to be supportive, but he becomes obsessed with tracking down the intruder.

The mystery gradually unravels as the shady background of the apartment’s former tenant emerges, and revelation of the identity of the intruder undermines the question of revenge. As in Farhadi’s other films, characters’ mistakes, honest or otherwise, compound each other. Ultimately, absolute blame is hard to assign.

The Salesman won two prizes at Cannes: best screenplay for Farhadi and best actor for Shahab Hosseini as Emad. Amazon Studios and Cohen Media will release it in the US on 9 December.

The King is (nearly) dead

Early on in Roberto Rossellini’s Taking of Power by Louis XIV (1966), we find Cardinal Mazarin on his deathbed. Mazarin’s doctors decide to bleed him; a priest advises him on the disposal of his wealth; finance minister Colbert briefs him on intrigues at the king’s court. The shots are lengthy, following the men around the chamber.

This remarkably deliberate sequence was considered quite striking at the time. In a story centered on Louis XIV, Rossellini devotes thirteen minutes to Mazarin. His impending death creates exposition about the ensuing power struggles and initiates a somber pace rather different from that of the standard historical film. The scene also reminds us that historical events have a tangibly material side, as when doctors confer gravely over the stools in His Eminence’s chamber pot.

Rossellini, who’s interested in the tactics by which Louis tames the nobility, doesn’t show us the King’s final hours. That morbid task is taken up by Albert Serra’s The Death of Louis XIV. Unlike Rossellini’s film, which is filmed in radiant high-key and shows sumptuous detail of fabrics and flooring, Serra’s treatment relies on chiaroscuro, with shadow areas broken by trembling candlelight. And while Rossellini’s PanCinor lens swivels and zooms around these apartments, Serra cuts among close views of faces, hands, and a steadily blackening gangrenous royal foot.

In the process Serra expands the physicality of the Mazarin sequence to the length of an entire film. Louis seems to linger for days, but we’re given no distinct sense of how much time passes; in only two shots do we glimpse the outdoors, in bleary light that might be dawn, drab afternoon, or dusk. The time is filled out by court rituals, such as the King’s doffing his hat to his entourage, and by the steady decline of his powers. He can’t swallow food and can barely take water or wine. Through it all, Louis feebly issues his final orders about matters of state and the disposition of his body. A long scene of the last rites is punctuated by a barely discernible fart. This is a movie centrally about a degenerating body.

Even more than Rossellini did, Serra probes the shaky state of medical science of the time. (Louis died in 1715, just as the Enlightenment was beginning.) When Louis’s leg contracts gangrene, the learned doctors debate whether to amputate it. A quack shows up with an elixir made of bull sperm and other recherché ingredients. At the end, the principal physician takes the blame for the king’s death and makes a remarkable apology directly to the camera. Before that, though, Serra has given us a three-minute shot of His Highness reproachfully staring at us (up top) while we hear a Kyrie Eleison somewhere offscreen. Another echo of film history: Louis is played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, who looked out apprehensively at us many years ago, in the seashore ending of The 400 Blows. It’s glib to say that cinema films death at work, but here the cliché gains some meaning.

Master of the weepie

Is any filmmaker more unfairly taken for granted than Pedro Almodóvar? For over thirty years, he has created sparkling, handsome entertainments that combine cinematic intelligence with outrageous eroticism and insidious emotional punch. His films revel in plot complications and edgy humor. Along the way he effortlessly deploys the techniques that make modern cinema modern, from flashbacks and voice-overs to subjective sequences and abrupt replays that fill in gaps.

He makes it all look easy, and gorgeous. After the drab grays and browns of Hollywood fare, what a pleasure to see a film packed with saturated primaries and bold designs. He proves that you can go as dark as you like in plotting and still make things look delightful.

His characters are clothes horses, I grant you, but not the least of his debts to Old Hollywood is the belief that we want to see presentable people in pretty costumes and settings. The world is ugly enough, he seems to say; why add to it? Seeing The Girl on the Train reminded me how glum American movies are determined to look. An Almodóvar apple looks good enough to eat, and a housekeeper’s roseate apron seems the height of chic. In this world, even refrigerator magnets evoke a Calder mobile.

These elegantly voluptuous tales make unabashed appeal to Hollywood genres: the screwball comedy (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, I’m So Excited), the illicit romance (Law of Desire, The Flower of My Secret), the twisty thriller (Live Flesh, The Skin I Live In), even the ghost story (Volver), and above all the melodrama—medical (Talk to Her) and maternal (High Heels, All about My Mother). He rolls Lubitsch, Sirk, and Siodmak into a nifty package, tied up with a ribbon bow of pansexuality.

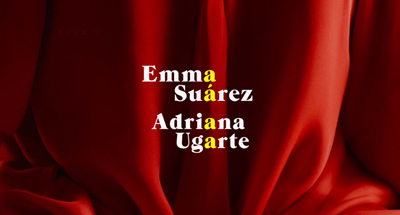

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

It’s all about guilt, passed from husband to wife and mistress and then to daughter and even daughter’s pal, with the obligatory recriminations and tearful confessions. The plot is continually surprising, yet every scene snicks into place. Neat parallels among couples develop quietly, and tiny hints planted in the beginning pay off. As usual with Almodóvar, the opening credits guarantee that you’re in assured hands. They also tease us with motifs. Here the film’s dual structure (two phases of life, two actresses) is suggested through lemon-yellow letters sliding into alignment.

The two women on my left started crying halfway through the movie. I tell you, this director is a credit to the species.

Special thanks to Michael Barker and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Classics. Sony will release Julieta in the US on 21 December.

We have earlier entries on Farhadi’s About Elly, on A Separation, and on The Past. We discuss Serra’s ingratiating Birdsong here, and Almodóvar’s cunning The Skin I Live In here.

The Salesman.

Long live French cinema at VIFF: A guest post by Kelley Conway

Chocolat (2016).

Kelley Conway, one of our colleagues here at UW–Madison, is an expert on French film; we talked about her latest book, a study of Agnès Varda, here. We invited her to contribute to our blog, and here’s the result.

David and Kristin introduced me to the pleasures of Vancouver and its superb festival, VIFF. Hats off to Alan Franey and the other programmers who created a strong and varied lineup of films. I saw excellent works from Romania (Sieranevada), Poland (The Last Family), Canada (Maliglutit), and Iran (The Salesman), but here I will address some of the strongest selections from France.

Shopping till she drops

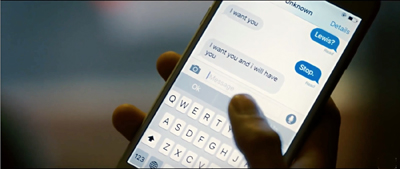

Now and then, the French make films that marry the conventions of art cinema and popular genres. François Ozon’s postmodern pastiche 8 Women evokes both the musical and the thriller. Claire Denis’s art-horror hybrid Trouble Every Day is contemplative and painterly, but also bloody and scary. Olivier Assayas continues the tradition by combining the traits of art cinema and Gothic horror in Personal Shopper, his second film featuring Kristen Stewart as a loyal assistant to a famous woman. While The Clouds of Sils Maria (2014) turns on the intense, shifting relationship between Stewart and an aging theater actress (Juliette Binoche), Personal Shopper is about a grieving young woman with little emotional connection to her celebrity boss (Nora von Waldstätten).

By day, Maureen (Stewart) makes the rounds of Chanel and Cartier, shopping for her employer; by night, she attempts to communicate with her recently departed twin, Lewis. The film’s links to the Gothic are established early on, when Maureen spends the night in a big, drafty house, awaiting a sign from her brother. Shutters bang, wind blows, and spectral figures attack. The supernatural is juxtaposed with the everyday; like so many twentysomethings, Maureen works in a job she hates in order to pay her rent.

Interestingly, she’s really good at this job. Wearing jeans and sneakers, she strides into exclusive boutiques, expertly chooses belts, bags, and baubles worth thousands, and transports them across Paris, skillfully navigating traffic on her scooter. At one point, she makes a quick trip to London to pick up a few dresses. Maureen tracks her employer’s movements via celebrity journalism on the internet and notes with satisfaction when the fashion maven wears the items she has chosen. But this is as close as Maureen gets to the rarefied world of high fashion; she is explicitly forbidden from trying on the beautiful things she covets. When she eventually breaks this rule, she must contend with the consequences.

Personal Shopper divided critics; the film’s Cannes premiere apparently elicited both hisses and a standing ovation. Stewart’s tendency to mumble here can indeed irritate. But the film’s conclusion offers a satisfying mix of suspenseful communication with the dead and art-house ambiguity.

Rape, violent videogames, and other breaches of Parisian decorum

Like Personal Shopper, Elle (Paul Verhoeven) plays with genre conventions. The film opens with a black screen and the offscreen sounds of moaning that could signify pleasure or pain. It’s pain, as it turns out: Michèle (Isabelle Huppert) is being raped on her living room floor by a masked intruder. Later, she calmly cleans up broken glass and soaks in the bathtub. When a circle of blood emerges from between her legs, staining the bubbles, she sweeps it away. She tells her close friends about the rape, invests in pepper spray and an ax, and takes a shooting lesson.

Are we in for a rape-revenge film? Or perhaps a poignant drama about a woman who finds the strength to rebuild her life after a traumatic event? Not exactly. The film references rape revenge and melodrama, only to veer away from these traditions toward an uneasy pairing of satiric comedy and thriller. The film is filled with events typical of a French film about middle aged Parisians in a bourgeois milieu: well dressed people get together for dinner in excellent restaurants, the successful completion of a project at work is celebrated with an elegant party; Michèle loses her mother to a stroke, but gains a grandchild.

But Michèle also runs a company that makes violent and misogynistic video games, is hated by her employees, and mocks her admittedly ridiculous mother and son in public. The film’s revelation of a traumatic event in Michèle’s childhood might have been used to motivate her cynicism, but traditional narrative causality is not on here. Peoples’ reactions to events in Elle are always somehow “off.” The film’s upbeat conclusion is particularly confounding: key characters appear to have changed for the better, but we don’t know why.

Is the film an allegorical treatment of the toxic relationships between men and women? Perhaps. Michèle exhibits behavior often attributed to men. In a reversal of Laura Mulvey’s classic analysis of voyeurism, she spies on a neighbor she finds attractive, holding binoculars in one hand and masturbating with the other. She mechanically performs sexual acts without even pretending to be interested in her partner. She sexually humiliates an employee and sleeps with a friend’s husband because she “felt like getting laid.”

Elle hangs tenuously by its manicured fingernails to European art cinema. The film was directed by Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven, better known for his Hollywood films Robocop (1987), Total Recall (1990), and Basic Instinct (1992) than for his work in Europe. Elle is a hybrid of Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down (1989) and The Piano Teacher (2001), borrowing Almodovar’s rape victim fascinated with her rapist and Haneke’s masochistic ice queen, also played by Huppert. Elle will intrigue and amuse some viewers and disgust others.

The film has been submitted to the Academy as France’s entry for Best Foreign Film. Huppert herself has never been nominated for an Oscar and she certainly deserved a “best actress” award for any number of the films she has made with Godard, Chabrol, Haneke, and Denis. This may be her year: her intriguing cipher in Elle and her subtle performance as a philosophy teacher in Mia Hansen-Løve’s Things to Come (2016), also playing at VIFF, both merit recognition.

Race under the big top

French superstar Omar Sy stars in Chocolat (released as Monsieur Chocolat), a Gaumont biopic about Rafael Padilla. Padilla was an Afro-Cuban who escaped abject poverty to become a famous clown in Belle Époque Paris. The film recounts the early period of Padilla’s career in a provincial circus, where he masquerades as a cannibal. The clown George Footit, played by James Thierrée (a grandson of Charlie Chaplin), sees his potential and they form a duo. Discovered by impresario Joseph Oller, they become “Footit and Chocolat,” and perform nightly at the Nouveau Cirque in Paris.

The film’s rags-to-riches tale condenses and alters the multiple phases of Padilla’s career; he actually enjoyed solo success in Paris before he met Footit. Still, the film succeeds at revealing the clown’s comic talent and physical grace. Padilla is initially naïve and good-natured, like the auguste clown character he plays in his act with Footit, but his rage grows at having to play the perpetual fool. He abandons the act and tries to mount a career in the theater playing Othello, but ends up back in a provincial circus, broke and sick.

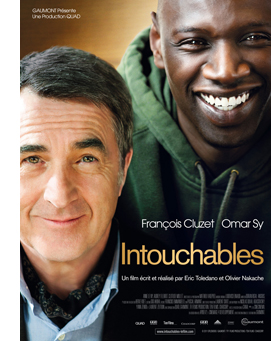

At first glance, the plot of Chocolat resembles that of Zouzou (Marc Allégret, 1934), another all-too-rare French film featuring a black protagonist. In Zouzou, Josephine Baker plays a laundress who becomes queen of the music-hall, but loses the man she loves (Jean Gabin) to her blonde best friend. Chocolat is more self-conscious about its racial politics and, in a way, can be seen as a riposte to the controversy around Sy’s earlier hit, Intouchables (Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano, 2011). In Intouchables, a wealthy, white, disabled man (François Cluzet) hires as his aid a young, black man (Sy) from the banlieue; friendship, humor, and mutual respect ensue. Intouchables was phenomenally successful at the box office, nearly overtaking the top-grossing French film of all time, Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis (2008). But it had a complicated critical reception. (See the codicil.)

At first glance, the plot of Chocolat resembles that of Zouzou (Marc Allégret, 1934), another all-too-rare French film featuring a black protagonist. In Zouzou, Josephine Baker plays a laundress who becomes queen of the music-hall, but loses the man she loves (Jean Gabin) to her blonde best friend. Chocolat is more self-conscious about its racial politics and, in a way, can be seen as a riposte to the controversy around Sy’s earlier hit, Intouchables (Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano, 2011). In Intouchables, a wealthy, white, disabled man (François Cluzet) hires as his aid a young, black man (Sy) from the banlieue; friendship, humor, and mutual respect ensue. Intouchables was phenomenally successful at the box office, nearly overtaking the top-grossing French film of all time, Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis (2008). But it had a complicated critical reception. (See the codicil.)

Mainstream French critics saw Intouchables as a fun buddy film, but others denigrated the film for its “televisual” look and its simplistic class politics. But after a Variety critic denounced the film for its “Uncle Tom-ism,” the French rallied around the film, presenting a more unified stance in favor of Intouchables as a welcome step in the move toward racial equality on the screen. Chocolat, for its part, underscores more overtly the racism Padilla experiences. The plot invents an episode in which he is arrested and tortured for not having his identity papers, and it shows his mortification at the sight of Africans performing their exoticism for the pleasure of Parisians at the Colonial Exhibition. Chocolat is well worth seeing for its lively portrait of Belle Époque popular entertainment and for its role in the ongoing debates about French cinema’s representation of race and its place in the blockbuster economy.

Simple, strongest

The Son of Joseph might be the only comedy made this year that pays homage to Bresson, Caravaggio, and the nativity story. In this austere yet witty film, brooding teenager Vincent (Victor Ezenfis) seeks the identity of his father. His single mother Marie (Natacha Régnier), a compassionate nurse, has kept this knowledge from him, and with good reason. Oscar (Mathieu Almaric) is a philandering and pretentious publisher who cannot even remember the names of his three legitimate children, much less acknowledge Vincent.

At a book launch party (in which Parisian intellectual pretension is deliciously skewered), Vincent spies on Oscar. Later, Vincent is hiding under a divan when the louche publisher beds his secretary. Vincent eventually finds a surrogate father in Oscar’s kindly brother Joseph, played by a Fabrizio Rongione, a favorite of Eugène Green and co-producers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. Like many of the adolescents in the Dardenne universe, Vincent is an angry kid: he shoplifts, watches as other boys prepare to torture a caged rat, and shuts out his mother. But he returns the tool he stole, rejects animal abuse, and reconnects with his mother.

American-born French director Eugène Green, director of La Sapienza (2014) and The Portuguese Nun (2009), brings to The Son of Joseph his characteristic compositional precision, an appreciation for Baroque art and music, and a distinctive way of filming conversations.

Green is clearly not interested in standard psychological realism or the mumbling delivery and the improvisation we see in some American indie films. Instead, he strives for the understated and precise acting we see in the work of Bresson or Akerman. Green’s actors deliver dialogue, whether arch or sincere, with perfect diction, often while looking directly into the camera. Green also opts for sparse, often symmetrical, compositions, and he usually dispenses with camera movement. Each shot renders the character’s line of dialogue in toto. “Simple things are, for me, strongest,” he said in 2015.

The static shots and direct address are never boring. One never tires of Green’s actors and Paris looks stunning here. Interiors are sparsely decorated and beautifully lit; exteriors typically consist of characters strolling through the Palais Royale or the Luxembourg Gardens. Moreover, Green insists upon the power of art: Caravaggio’s Sacrifice of Isaac and Georges de la Tour’s Joseph the Carpenter figure prominently here, as does an extraordinary singing performance in a church.

The film’s rigorous design does not prevent it from exuding hope and a touching sincerity. The concluding scene on the beach in Normandy retains the film’s minimalist design and rewards viewers who remember Au hasard, Balthazar, but also suggests the formation of a new family and the redeeming power of love.

Upcoming U.S. releases: Sony Pictures Classics has slated Elle for 11 November. Kino Lorber will release The Son of Joseph on 12 January, while Personal Shopper (IFC Films) is scheduled for 10 March. Chocolat does not yet have a U.S. distributor.

Charlie Michael traces the critical response to Intouchables in “Interpreting Intouchables: Competing Transnationalisms in Contemporary French Cinema,” SubStance 133, Vol. 43, no. 1 (2014), 123-137.

Eugène Green’s remarks about simple things comes from his Film Comment interview on La Sapienza. David has written entries on Green’s compass-point editing here and here.

The Son of Joseph (Eugène Green, 2016).