Archive for November 2016

Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT

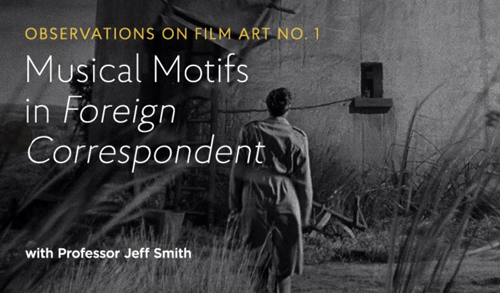

DB here: Here’s another guest contribution from colleague, Film Art collaborator, and pal Jeff Smith. He inaugurates a series of entries tied to our monthly Observations on Film Art videos on FilmStruck.

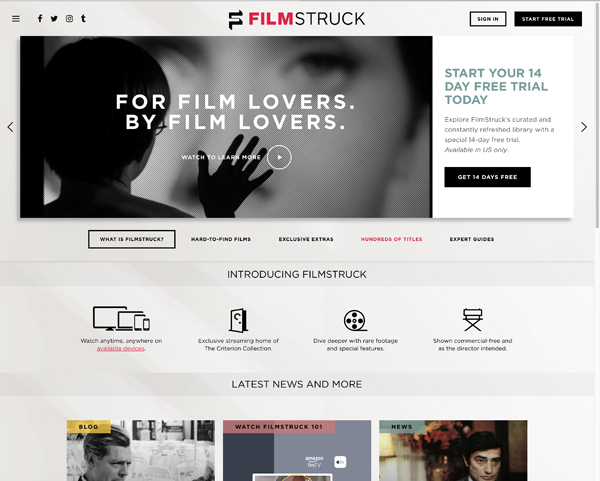

About a month ago, a new streaming service for film lovers debuted. Its name is FilmStruck and it’s a joint venture of Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Collection.

As regular readers of the blog already know, David, Kristin, and I have launched a series for FilmStruck. Every month, we’ll be featured in short videos that offer appreciations of particular films and filmmakers. In baseball lingo, I got the leadoff spot. As the first up, I offered an overview of the principal musical motifs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Below is a supplement to the video that goes into a little more depth regarding the way Alfred Newman’s score for Foreign Correspondent fits into the film’s larger narrative strategies.

Fair warning: there are some spoilers in what follows. Some of you who are FilmStruck subscribers or owners of the Criterion disc may want to watch this Hitchcock classic before proceeding.

Founding a Hollywood dynasty

Alfred Newman.

If you were looking for someone whose work epitomized the qualities of the classical Hollywood score, Alfred Newman would be a pretty good candidate for the job.

Newman’s career in Hollywood began when Tin Pan Alley stalwart, Irving Berlin, recommended him for the 1930 musical, Reaching for the Moon. Having worked for years as a music director on Broadway, Newman planned to stay for only three months. But the lure of the Silver Screen was too strong. Newman spent the next forty years working in Hollywood.

In 1931, Newman became the musical director at United Artists, working mostly for producer Samuel Goldwyn. He also established himself as one of the industry’s leading composers, contributing to nearly ninety films over the course of the 1930s and earning nine Oscar nominations in the process. Newman’s most memorable early scores included such titles as The Prisoner of Zenda, The Hurricane, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Wuthering Heights. Eventually, he would leave Goldwyn to take over the music department at 20th Century-Fox, a position he held for more than twenty years.

Alfred, however, would be just one of several Newmans who would make the name synonymous with the Hollywood sound. Alfred would establish a film composing dynasty that would come to include his brothers Lionel and Emil; his sons, Thomas and David; and his nephew, Randy.

Overture, hit the lights….

If you asked most film music aficionados for their favorite Alfred Newman scores, I suspect Foreign Correspondent would be pretty low on the list. Most fans of the composer’s work would likely opt for one of the later Fox classics he scored, such as How Green Was My Valley (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Captain from Castile (1947), or The Robe (1953). Yet, if you want to get a handle on the basic features of the classical paradigm, Foreign Correspondent’s typicality makes it more useful as an exemplar. Newman’s music neatly illustrates several of the traits commonly associated with the classical Hollywood score’s dramatic functions.

One of these characteristic traits is Newman’s use of leitmotif as an organizational principle. Foreign Correspondent’s score is organized around five in all. The first is a theme for the film’s protagonist, Johnny Jones. The second is a theme for Carol, Johnny’s love interest in the film. As is typical of studio-era scores, both themes are introduced in the film’s Main Title.

Like an overture, the Main Title previews the two most important musical themes in the film. The A theme is upbeat, sprightly, and lightly comic. It captures some of Johnny’s ebullience and masculine charm, and it helps establish the tone of the early scenes, which draw upon the conventions of the newspaper film. The B theme is slower and more lyrical. It features the kind of lush orchestrations for strings that became a hallmark of Newman’s style.

Each theme roughly correlates with the dual plot structure common to classical Hollywood narratives. The A theme previews the main plotline focused on Johnny’s efforts as an investigative reporter. The B theme previews the story’s secondary plotline: the budding romance between Johnny and Carol.

Both themes recur throughout the remainder of the movie. In fact, Johnny’s theme returns even before the opening credits have ended, appearing underneath a title card valorizing the power of the press. In contrast to the lively, spunky version heard earlier, Newman gives it a maestoso treatment, slowing the tempo and orchestrating it for brass. In this instance, Newman’s arrangement of Johnny’s theme is attuned less to the brashness of his character and more to the social role that newspaper reporters play as a source of information to the world.

Up until this point, the music simply primes us for what is to come. Johnny’s theme returns about two minutes later when he is first introduced.

The reprise of his theme makes explicit the Main Title’s tacit association between music and character. Here, though, it plays in a jazz arrangement as a slow foxtrot. Newman’s arrangement nicely captures the tone of these early scenes, which display the lightness and pacing of other newspaper comedies.

It returns 22 more times in the film. In all, Johnny’s theme accounts for more than a quarter of the film’s 94 music cues. Usually, the theme functions to underline Johnny’s heroism and resourcefulness as in the scene where he gives chase to Van Meer’s assassin. At one point, Johnny even whistles his theme. This occurs in the scene where he eludes a pair of suspicious men posing as police by pretending to draw a bath and crawling out the window.

In contrast, Carol’s theme is used less frequently, appearing in about thirteen cues in all. After its introduction in the main title, it returns when Johnny and Carol first meet at the luncheon sponsored by the Universal Peace Party. Johnny unknowingly insults Carol, first by mistaking her for a publicist, and then by expressing skepticism about the organization’s mission, griping about well-meaning amateurs interfering in international affairs. Newman’s theme hints at Carol’s attraction to Johnny despite his obvious boorishness. The music says what the characters can’t or won’t say. As Johnny and Carol trade insults, Carol’s theme captures the romantic spark that lurks beneath their badinage.

The theme’s other uses often work along similar lines, providing an emotional resonance to the couple’s expression of feelings for one another. A good example is found in the scene where Carol and Johnny huddle together on the deck of a steamship. Here, as a pair of refugees, each member of the couple declare their love for one another and their desire to marry.

Music for the hope of the world

In addition to these two principal themes, the score also utilizes three other themes and motifs to represent important secondary characters. A theme for Professor Van Meer is introduced when Johnny spots him getting into a taxicab.

It returns nine more times in the film in scenes that feature the character or make reference to him.

The theme itself is simple, slow, stately, and quite frankly, a little bit boring. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the multiple references to a “Van Meer Theme” on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent, the music would simply blend into the other material that surrounds it.

The orchestration of the theme for solo wind instruments, usually an oboe, gives it a kind of pastoral feeling. The image of peaceful shepherds is likely an appropriate one for Van Meer, who functions as a stand-in for a global desire to avoid armed conflict. Yet, both the character and Newman’s musical theme for him seem nondescript, making Van Meer seem like little more than the walking embodiment of an abstract ideal of world harmony.

Truth be told, Van Meer mostly operates in Foreign Correspondent as the classic Hitchcock MacGuffin–that is, the thing the characters all want, but with which the audience need not concern itself. When Van Meer appears to be assassinated, it sets in motion a chain of events that uncovers a conspiracy organized through Steven Fisher’s World Peace Party. Van Meer is the object that all the characters want to find, and the search for him drives the narrative forward. Yet the character himself has about as much personality as the microfilm in North by Northwest. Newman’s nondescript melody seems to fit the “blank slate” quality of Van Meer himself.

Like the classic MacGuffin, Van Meer’s function as something of an empty vessel allows his theme to be used several times late in the film in scenes where the character isn’t physically present. Although the norm is to use characters’ themes or leitmotifs when they are onscreen, Newman’s treatment of Van Meer shows they can evoke absent characters. This occurs, for example, in a scene where Scott ffolliot explains to Stephen Fisher that he’s arranged for the kidnapping of Carol. Fisher asks ffolliot why he would do such a thing, and ffolliot replies that he wants to know where Stephen has stashed Van Meer.

As we’ll see, Fisher has a theme of his own that itself appears several times in this same scene. But the use of Van Meer’s theme in this context becomes a way of signifying both the character and the peaceful values that he represents – that is, values that Fisher seeks to destroy.

And though Van Meer’s music is a bit dull, the theme proves a bit more interesting when one considers the way it works within Hitchcock’s larger strategies of narration. At a key point, Hitchcock and Newman use the Van Meer theme to mislead the audience about what has just transpired onscreen. I’m referring here to the moment when Van Meer appears on the steps just as the Peace conference in Amsterdam is about to commence.

The theme is cued by Johnny’s glance offscreen after briefly chatting with Fisher, his publicist, and a diplomat. Hitchcock cuts to a shot from Johnny’s optical POV that shows Van Meer climbing up the staircase. We return to Johnny, who smiles and walks out of the frame. Johnny and Van Meer meet in a two-shot where the former offers a warm greeting. A cut to Van Meer’s reaction, though, reveals a blank stare, even as Johnny tries to remind the elderly professor of their previous encounter in the taxi.

The moment is an important one, but before the viewer can even grasp its significance, the two men are interrupted by a request for a photograph. Hitchcock then tracks in on the newsman, who surreptitiously sneaks a gun next to the camera he is holding. He pulls the trigger, and Hitchcock cuts to a brief insert of Van Meer, who has been shot in the face.

As I noted earlier, the assassination we witness is a key turning point in the story, and Hitchcock handles the scene with considerable finesse. Almost unnoticed, though, is the fact that Hitchcock and Newman cleverly use Van Meer’s musical theme as a form of narrative deceit. At first blush, the musical theme helps to reinforce Van Meer’s identity, serving the kind of signposting function that some film music critics believed was a hackneyed device. As we later learn, though, the murder victim is not Van Meer, but rather a double killed in his place to foment international tensions. This information ultimately recasts the old man’s seeming failure to recognize Johnny. As Van Meer’s double, these two men have never actually met.

Has Hitchcock played fair in using Van Meer’s theme for a character that is not Van Meer but only looks like him? Perhaps, but the creation of this red herring is justified if one considers the fact that composers frequently write cues meant to reflect or convey a character’s point of view. Every composer must make a choice about whether to write a cue from the particular perspective of the character or the more global perspective of the film’s narration. Newman might have opted for conventional musical devices that connote suspense (ostinato figures, string tremolos, low sustained minor chords), and these would have signaled to the viewer that Van Meer is in peril, thereby creating a heightened anticipation of the violence that erupts in the scene. Instead, though, following the visual cues provided by Hitchcock’s cinematography and editing of the scene, Newman plays Johnny’s perspective and his recognition of Van Meer as he approaches the building’s entrance. By combining two common tactics–leitmotif and character perspective – Newman and Hitchcock briefly mislead the audience in order to create two surprises: the first when it appears that Van Meer is killed and the second when Van Meer is discovered inside the windmill and proves to be very much alive.

Menace (without the Dennis)

There is also a brief six-note motif used to signify the conspirators as a group. Labeled the “menace” motif, it is introduced just after Van Meer’s apparent assassination. In the chase that follows, Newman alternates between the “menace” motif and Johnny’s theme in order to sharpen the conflict and to capture the ebbs and flows of our hero’s dogged pursuit of the bad guys.

The motif returns, though, at just about any point where one of the group’s henchmen gets up to no good. In the scene inside the windmill, the menace motif appears several times to underscore the kidnappers’ nefarious scheme. Johnny sneaks inside the windmill, and after locating Van Meer, he tries to rescue him only to find out that the elderly professor has been drugged. As Johnny tries to figure out his next move, muted trumpets play the “menace” motif, signaling the kidnappers’ approach and thereby heightening the scene’s suspenseful tone.

Here again, Newman’s thematic organization reinforces a larger narrative tactic in Hitchcock’s film. Herbert Marshall serves as the typical suave villain commonly found in the Master’s oeuvre and Edmund Gwenn steals the show as Johnny’s would-be assassin, Rowley. But the rest of the conspirators are a largely undistinguished lot, and the use of a single motif for the group in toto reflects their relative impersonality. Unlike North by Northwest, where Martin Landau makes a vivid impression as Van Damm’s reptilian assistant Leonard, this spy ring seems to be filled out by thugs from Central Casting.

Father, leader, traitor, spy

Besides motifs for Johnny, Carol, Van Meer and the conspirators, there is also a short motif for Carol’s father, Stephen Fisher. It is harmonically and melodically ambiguous, structured around the rapid, downward movement of a chromatic figure.

In classical Hollywood practice, a leitmotif is usually introduced when the character first appears onscreen. But in an unusual gesture, Newman and Hitchcock resist this convention. The motif does not appear until more than eighty minutes into the film in the aforementioned scene just before ffolliot tries to blackmail Fisher into divulging Van Meer’s location.

By withholding Fisher’s motif, Hitchcock and Newman avoid tipping their hand too early. Since Fisher is later revealed to be the leader of the spy ring, the score circumspectly avoids comment on him in order to preserve the plot twist.

Several cues featuring Fisher’s motif return in the scene where Johnny, Carol, ffolliot, and the other survivors of the plane crash cling to wreckage waiting to be rescued. Carol spots the plane’s pilot stranded on its tail.

He swims over to the group and clambers about the wing. The pilot’s added weight threatens to upend the wing, thereby endangering everyone sitting atop it.

Recognizing this, the pilot asks the others to let him go so that he can simply “slip away.” Fisher overhears this exchange and decides to remove his life jacket and dive into the waters himself, leaving room on the plane’s wing for the rest of crash’s survivors.

The harmonic and melodic ambiguity of Fisher’s motif is most pronounced here, a moment where the character’s duality is also most clearly revealed. Is this a heroic act of self-sacrifice, an act of atonement for the damage Fisher has done to both his daughter’s reputation and his organization’s peaceful cause? Or has Fisher taken the coward’s way out, committing suicide in order to avoid facing the consequences of his actions?

Newman’s rather opaque musical motif doesn’t seem to take sides on this question, leaving Fisher’s motivation more or less uncertain. But this, too, is in keeping with the basic split between the character’s public and private personae. Introduced earlier as Carol’s father, Fisher appears to be cultured and debonair. Yet, when he seeks to extract information from a reluctant captive, Stephen resorts to the physical torments used by two-bit gangsters to make mugs talk. Like those gangsters in the 1930s, Fisher refuses to be taken alive and is swallowed up in briny sea. Still, his action does help to save other lives, and in this way, Fisher enables Carol to find a small measure of grace in the final memory she will have of him.

Putting earworms inside actual ears

As the principal composer of music for Foreign Correspondent, Newman had a major impact on the film’s ultimate success. Yet Newman was not responsible for the music that has engendered the most attention in critical work on the film. I’m referring here to two source cues written by Fox staff arranger, Gene Rose, that are featured in the scene where Van Meer is psychologically tortured. His captors use sleep deprivation techniques to elicit van Meer’s cooperation, including bright lights and the repeated playing of a jazz record. The two cues received rather cheeky descriptions on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent: “More Torture in C” and “Torture in A Flat.”

The use of jazz for these cues is likely a little bit of wicked humor on Hitchcock’s part. Despite its popularity as dance music in the 1930s, some listeners undoubtedly believed that jazz was little more than noise with a swinging rhythm. From a modern perspective, though, the scene eerily anticipates the “enhanced interrogation” techniques that would become notorious at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib. As The Guardian reported in 2008, US military played Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” at ear-splitting volume for hours on end, both at Guantanamo and at a detention center located on the Iraqi-Syrian border. At the other end of the musical spectrum, one of the other pieces played repeatedly was “I Love You” sung by Barney the purple dinosaur. Presumably the first was selected because of its aggressiveness, the latter because of its insipidness. But the Barney song has the distinction of being characterized by military officials as “futility” music – that is, its use is designed to convince the prisoner of the futility of their resistance.

Although, in 1940, Hitchcock could not have envisioned the use of heavy metal and kidvid music as elements of enhanced interrogation, the scene from Foreign Correspondent is eerily prescient. Viewed today, the scene also carries with it a strong element of political critique insofar as it associates such psychological torture techniques with a bunch of “fifth columnists” who are willing to commit murder and even engineer a plane crash in order to achieve their political ends. Touches like these make Foreign Correspondent seem timely today, more than seventy-five years after its initial release.

Alfred Newman the Elder

After Foreign Correspondent, Alfred Newman would go on to score more than a hundred and thirty feature films, and earn several dozen more Academy Award nominations. His nine Oscar wins remain an achievement unmatched by any other film composer. Newman died in Hollywood in 1970 at the age of 69, just before the release of his last picture, the seminal disaster movie, Airport. His work on Airport received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, the 43rd such nomination of his long and distinguished career.

For some film music scholars, Newman’s death marked the end of an era, as his career was more or less contemporaneous with the history of recorded synchronized sound cinema in Hollywood. As fellow composer Fred Steiner wrote in his pioneering dissertation on the development of Newman’s style:

As things are, we can be grateful for the dozen or so acknowledged monuments of this twentieth-century form of musical art— absolute models of their kind— that Newman did bestow on the world of cinema. Fashions in movies and in movie music may come and go, but scores such as The Prisoner of Zenda, Wuthering Heights, The Song of Bernadette, Captain From Castile, and The Robe are musical treasures for all time, and as long as people continue to be drawn to the magic of the silver screen, Alfred Newman*s music will continue to move their emotions, just as he always wished.

Because of its typicality, Foreign Correspondent may well seem like a speed bump on Newman’s road to Hollywood immortality. Yet it remains a useful introduction to the composer himself, who along with Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, is part of a triumvirate that would come to define the sound of American film music.

For more on music in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, see Jack Sullivan’s encyclopedic Hitchcock’s Music. For more on the production of Foreign Correspondent, see Matthew Bernstein’s Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. Readers interested in learning about Alfred Newman’s career should consult Fred Steiner’s 1981 doctoral dissertation, “The Making of an American Film Composer: A Study of Alfred Newman’s Music in the First Decade of the Sound Era,” and Christopher Palmer’s The Composer in Hollywood.

Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music includes Newman’s own account of his work for the Broadway stage before coming to Hollywood. Readers interested in an overview of the classical Hollywood score’s development should consult James Wierzbicki’s excellent Film Music: A History.

Alfred Newman conducts his most famous film theme, Street Scene, in the prologue to How to Marry a Millionaire (1953).

ARRIVAL: When is Now?

Arrival (2016).

DB here:

A lot of today’s movie storytelling is nonlinear. Filmmakers rely on flashbacks, replays, and voice-overs in order to shape our experience, sometimes in fairly daring ways. In Hollywood these strategies got consolidated in the 1940s. Or so I argue in my Reinventing Hollywood, now in copy-editing (or as the University of Chicago Press calls it, copy editing).

The question today is the same as back then: How do ambitious filmmakers handle these conventions? I think the ambitious writer or director faces at least three tasks.

How do I innovate—that is, how do I treat time shifts in a fresh way?

How do I motivate the shifts—that is, justify the scrambling of chronology?

How do I make the new version clear enough for audiences to follow?

Novelty, motivation, and clarity seem to me essential considerations for a filmmaker who wants to play with time and the viewpoint shifts that often come with it.

I’m not alone in thinking that Arrival succeeds in creating its particular engagement with the audience by tackling my three tasks. Director Denis Villeneuve and screenwriter Eric Heisserer innovate in handling time, and they in turn carefully motivate the device and find ways to make it clear to the audience. Today I want to consider how this all works. I have to assume you’ve seen the film, so of course there are spoilers.

Back to what future?

Cinema didn’t invent broken timelines; they’ve been used in literature for centuries. The Odyssey has blocks of flashbacks. Literature benefits from the fact that language has simple and direct ways to signal jumps in time.

For example, the writer working in English can make flashbacks clear though time tags and verb tense. Take this passage from John Le Carré’s novel Our Kind of Traitor. We’re told that on Sunday morning an anxious Perry Makepiece is climbing into a chauffeur-driven Mercedes. Then:

Last night, returning to the Deux Anges from their supper party, Perry had caught Madame Mère’s boot-button eyes peering at him from her den behind the reception desk.

“Last night” tells us we’re in an earlier period, and that information is reinforced by the past perfect tense of “had caught.” Page layout helps too: the entire flashback to the previous night is blocked out within extra spaces separated by a centered ★.

After recounting what happened when Perry returned to his hotel last night, Le Carré returns to the present time, the narrative Now, with a turn to the simple past tense:

The Mercedes stank of foul tobacco smoke.

Apart from the change of tense, the Mercedes mention reminds us of Perry’s morning trip. In addition, the shift back to the present opens a new section marked by ★.

On my three dimensions: There’s nothing innovative about this instance, though Le Carré will try some unusual things elsewhere in the book. The flashback is motivated by Perry’s remembering last night, and it’s made clear to the reader through repetition of several cues.

But what do we do with this passage?

I remember the scenario of your origin you’ll suggest when you’re twelve.

The tenses are out of whack, thanks to that “you’ll.” Then there’s the very meaning of the word “remember.” (Replacing the phrase with “I imagine.”) How can you remember something that has yet to happen? This isn’t just a casual slip. The speaker goes on to report an entire conversation that uses the future tense: “you’ll say bitterly,” “I’ll say,” “That will be in the house on Belmont Street,” and so on.

This passage comes near the start of Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” the source of Arrival. The story is what literary scholars call an apostrophe, a discourse addressed to an absent person. Louise Banks explains how her daughter came into existence. The story begins with Louise’s husband asking one evening, “”Do you want to make a baby?” It’s this point in time that’s marked as the present (and is rendered in present tense), but the bulk of the story shuttles between the past and the future. From the benchmark moment we get, in other words, flashbacks alternating with flashforwards.

On my three-dimensional scale, Chiang gets credit for innovation. Stories told in the future tense are pretty rare, especially when the events are presented as memories. And he makes the narrational premise clear. After a few pages, it’s established that Louise purports to know things yet to happen. The tenses cooperate: Present for the baby-making moment, past tense for the past events, future for the future ones.

We’re used to characters who know their past, but how can one know her future? For the story-maker that reduces to: How to motivate Louise’s knowing the future?

The answer is aliens. In the past, Louise met her husband when floating seven-legged creatures came to earth. As a linguist, she was assigned to learn the Heptapods’ language. Gradually she discovered that they had a mentality that refused causality and sequence in favor of a holistic view of time. Their language, to put it crudely, gave them access to past, present, and future.

By learning their language Louise absorbed, to some extent, their world-view. (Yes, the untenable Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is invoked.) Her precognition allows her to know, moments before she and her husband conceive the girl, what her daughter will do from her childhood right up to her early death. Louise also knows that she and her husband will divorce and find new partners. For us, these episodes are rendered as flashforwards from the Now, even though for Louise they are, paradoxically, memories (of things yet to happen).

Chiang’s story explores the emotional effects of knowing the future and deciding not to try to change it. For all I know, this may be another innovation in the realm of speculative fiction. Most time-travelers seek to alter the past or the future, but Louise is aware of the paradoxes of time travel. If you know the future, you can freely decide to alter it by choosing differently at crucial junctures. Marry somebody else, and you’ll change what happens afterward, so you didn’t really know the future. But Louise comes to believe that free will is a part of linear, causal thinking, the sort that the Heptapods have given up.

The existence of free will meant that we couldn’t know the future. And we knew free will still existed because we had direct experience of it. Volition was an intrinsic part of consciousness.

Or was it? What if the experience of knowing the future changed a person? What if it evoked a sense of urgency, a sense of obligation to act precisely as she knew she would?

The Heptapods know that they will need help from Earth in 3000 years, and they presumably know that they’ll get it, but to fulfill that future they need to ask. The story’s analogy is to the daughter’s wanting to re-hear a story she knows by heart. As a story reader replays a known tale, the aliens perform the incidents that make things inevitable.

So Louise accepts her role in playing out whatever future is predetermined. For this reason she can address her (future) daughter with foreknowledge of the pains and delights that are coming, accepting them as part of a seamless whole.

Image + sound + time

Lacking a tense system like language, cinema has devised other time signals. In the classic flashback we get a combination of them. We’re presented with a speaking or remembering character, a track-in to her, perhaps some music, a hint in the dialogue that we’re going into the past, a dissolve, perhaps a voice-over indication, and then a scene obviously situated in an earlier period. Filmmakers have discovered ways of altering some cues (cuts replace dissolves, tight close-ups replace track-ins) and deleting others (music and voice-over seem fairly optional now). Other cues are added for clarity, such as a different color palette for scenes in the past, or perhaps slow-motion imagery, or sound from the past that leaks in over imagery in the present.

Of course films use written and spoken language too, and so they can deploy tenses and time tags. Sometimes that can help us understand the time status of the scenes we’re seeing.

Voice-over is very helpful here. Take another Le Carré example, this time from Fred Schepisi and Tom Stoppard’s adaptation of The Russia House. Play the clip below and you’ll see what I mean.

Katya’s delivery of the covert manuscript, given on the image track, seems at first to be in the present. But the voice-over office conversation, only gradually shown through intercutting, is later than the Moscow incidents we see. So the present, the opening Now, is established on the soundtrack, while the image is in the past. As in fiction, the twin cues of verbal tense (“she visited”) and a time tag (“a week ago”) confirm the status of the Bookfair scene. The innovation comes when Stoppard and Schepisi don’t frame the Moscow scene by offering us the present-time office conversation before we see Katya–in effect, establishing the Now before showing us the Then. It’s an economical tactic of exposition, an elliptical revision of the phone conversations about the police investigations in M.

A voice-over can be in same time period as the images, of course, if it’s an inner monologue, a report on what a character is thinking at the moment. But voice-over commentary is often positioned as in the present with the images assumed to be in the past.

The voice-over present can be specified, usually through a lead-in scene showing the speaker recounting or recalling things at a particular time. Or the voice can be in a vague present, a zone we take as simply “after the events of the story.” It’s this no-man’s-land Now that leads us astray in Laura and other tricky films from the 1940s onward. Uncertainty about who’s speaking from when can be a source of interest in its own right. In Road Warrior, the revelation of the source of the opening voice-over provides the final surprise of the film.

So Heisserer and Villeneuve had an opportunity to follow Chiang in using the future tense in the voice-over for Arrival. It would surely have been an innovative move for a film. But they don’t do it. Why?

From premise to twist

Flashbacks are temperamental little buggers. Hard to know when and how to use them.

Eric Heisserer, 150 Screenwriting Challenges

Heisserer was a keen fan of Chiang’s story and spent years trying to get backing for a film version. He recounts various difficulties in online interviews (here and here, for example), but I want to focus on a couple of other problems he faced.

In a general way, the film respects the thrust of the story. At the close, you realize that Louise has gained the ability to anticipate the future, thanks to learning Heptapod. But on a fine-grained basis, the film doesn’t spell out her ability as frankly or as early as the story does.

The first image, a view out onto the patio and the lake, shows no people, just a table with a wine bottle and a couple of glasses. Louise’s voice-over does address someone absent: “I used to think this was the beginning of your story.” But the point in time and the person addressed are far less specific than in the literary version. Then we get a quick burst of images of a baby, then a little girl playing with Louise, and soon a young woman lying dead in a hospital bed. This cascade of impressions ends with a shot of Louise walking mournfully down a hospital corridor, followed by a fade-out. Fade up on her striding into a campus building and attending her lecture. Over this we hear her voice-over.

But now I’m not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings. There are things that define your story beyond your life. Like the day they arrived.

And then we’re confronted by the Heptapods, as broadcast on worldwide TV, and Louise’s getting the assignment to talk with them.

The first shot, of the patio, is enigmatic, but fairly soon we get the sense that Louise is addressing her dead daughter. We seem to have a classic prologue. (Compare the opening death of Starlord’s mother in Guardians of the Galaxy.) Across three minutes, we see a mother loving and losing her daughter. Our default assumption is that after the daughter’s death, she has become solitary and emotionally numb. She doesn’t interact with people on her way to her classroom, and when she goes home alone she watches TV reports with a kind of blank anxiety.

The film sets up a schema: The grieving mother needs to get out of herself, and the assignment to communicate with the aliens would seem to do that. Eventually she finds love with the physicist Ian Donnelly as well. This redemption schema is probably reinforced for some viewers by memories of Gravity (2013), another movie about a withdrawn mother who channels her sorrow into heroic action.

As the alien encounters unfold, the film’s narration starts to sprinkle in more images of the lost daughter at different ages. But the images show up rather late. At about 48 minutes, there’s a brief, out-of-focus image of a baby; at about 51:00, a glimpse of the little girl wading. Not until about halfway through the film (57:00) is there a fairly sustained scene between mother and child, when the girl shows Louise a picture of her imaginary TV show. That’s when we learn that the father isn’t with them any more. Later shots of the daughter are salted through the scenes of the increasingly tense confrontation with the Heptapods.

Just as we’re encouraged to take the daughter’s birth, childhood, and death as a prologue that precedes the alien investigation, we’re inclined to take these interruptive shots of the girl as flashbacks. Louise seems to be remembering her daughter.

At about 82 minutes something happens that challenges our basic assumption. In another household scene, the daughter asks about the “science-y” term for a win/win situation, and Louise is stumped. The narration shifts us back to the tent at the site, Ian mentions the term “non-zero-sum game.” Then we’re whisked back to the scene with the daughter, and Louise repeats that.

I felt a bump there. If the scene with Ian’s use of the term comes after the death of the daughter, during the alien encounter, how can Louise “remember” it to relay it to the daughter? For many viewers (probably not all), this opens the possibility that the “prologue” tracing the daughter’s childhood takes place after the alien adventure, not before. The reinforcement for this, visible to me only on second viewing, is that the earlier glimpses of the girl’s growing up are always triggered by scenes showing Louise learning the Heptapod’s language.

The filmic narration creates a sort of duck/rabbit Gestalt switch. Things we thought were past are future, things we thought were present are past. If the patio shot is the benchmark Now, the growth and death of the girl are the future and the Heptapods’ visit becomes a sustained flashback.

Now we see why Louise’s introductory voice-over lacks the future-tense sentences that are so startling in the novella. Including those would have been too strong a hint about the status of the mother-daughter shots. Instead, the opening voice-over uses only the past tense (“I used to think”) and the present (“But now I’m not so sure”). Another moment in the voice-over tilts us toward thinking of the image bursts later as flashbacks: we hear Louise murmur over the dead girl. “Come back to me.” Her yearning to reconnect to her daughter inclines us even more to consider the visions of the girl later as flashbacks.

Redundancy is your friend

Okay, pretty innovative—and an interesting departure from Chiang’s story. Instead of telling us at the outset that Louise has precognition, the film holds that as a surprise, and makes us think that her anticipations are actually memories. And we have motivation: as in the story, it’s the alien encounter that endows Louise with precognition. But what about my third consideration, clarity?

I said that not everybody will probably catch the echo of Ian’s “non-zero-sum game.” The last half-hour of the film devotes itself partly to reiterating the news that Louise can discern the future.

Her impulsive visit to the Heptapods late in the film explains why they dropped by. They know they’ll need humans’ help in the future, so they come to make that future happen. At the ninety-minute mark, one speaks, and we get a big old subtitle: “Louise sees future.” If you doubt the Heptapod’s insight, another flashforward soon shows Louise explaining to her daughter why her dad left. Louise “made a mistake” by telling him about a rare disease—presumably the one that would kill their daughter. We’re left to understand that after she told him that she knew their child was fated to die young, he couldn’t take it. The delayed exposition, judiciously repeated, lets the pieces fall into place. We may even start to surmise that Ian is to be that husband, earlier identified as a scientist.

Like the aliens’ sentences, the film is circular. Heisserer told Vox:

When I completed the first draft and the bookends of the first three pages and the final three pages, it felt like I was drawing a narrative circle and I just closed the loop. That felt right.

The narration buckles the film shut by returning to the view of the patio, which is intercut with Louise and Ian embracing. Ian proposes that tonight they make a baby. The fact that Heisserer’s script displaces to the very end what was the opening of Chiang’s story is a fair index of the transformation he has wrought. What was a premise of the novella becomes a reveal in the film.

But the motivation is the same. Flashforwards aren’t exactly parallel to flashbacks, as far as viewer psychology is concerned. Flashbacks are assumed to be veridical unless there’s reason to doubt them (as in trial and investigation films, where people give differing versions of events). The default is that flashbacks really happened, unless there are contrary indications.

Flashforwards, on the other hand, can be of two types. They might proceed from the film’s external narration. In Easy Rider, Petulia, and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? we get glimpses of future events that no character can know. In such cases, the images are usually enigmatic enough that we can’t be sure about the import of what we’re seeing. Flaming motorcycles, the protagonist tossing a bouquet into the water, a brief cutaway to a man in a police wagon (below, from They Shoot Horses): these are teases, not fully informative scenes, and they interrupt the main present-time action.

Alternatively, more identifiable flashforwards are usually motivated as a character’s precognition. They aren’t necessarily reliable. Flashbacks normally represent “actual” pasts, but flashforwards coming from mediums, psychics, or possessed children are only possible futures. Indeed, one task in such films is to prevent the apparent future from coming to pass, as in Minority Report and It Happened Tomorrow. The past is closed, but in subjective flashforwards, the future is usually open.

How, then, do we motivate trustworthy flashforwards? Here. by having infallible aliens certify them. Like “Story of Your Life,” Arrival assures us that Louise’s premonitions are accurate. It’s just that Chiang’s story proposes that early on and then shows how she achieved them. The film is trickier. It misleads us into thinking she has memories of the past when she is actually learning to see the future. She learns more quickly than we do, though eventually we catch up with her.

We’ve also learned that flashforwards can masquerade as flashbacks—if they’re deployed carefully enough.

Adding the ride

Explaining, very clearly, that Louise is knowing her future is only one task of the last stretch of the film. Another task is preventing a military attack on the aliens.

In Chiang’s story, the creatures simply leave. But Heisserer has explained that he felt the plot needed more conflict, so he added the prospect of brass hats eager to confront the visitors. The Heptapods, Louise suggests, have landed at various places around the world to induce nations to forget their differences in a common purpose. The Americans are suspicious, and General Shang of China breaks away from the alliance and takes steps to attack the ship near Shanghai.

Of the civil turmoil and military threat that fill out the plot, Heisserer noted in the same Vox interview:

The story doesn’t really have any conflict of that nature. It doesn’t need to. It’s a lovely literary conceit in its own right and works without that drama.

However, our early attempts a building this narrative without that conflict added felt very flat, and felt like there were no stakes. There was no ride. The more we played with it, the more Denis and I both realized that if aliens did land on earth and the public didn’t get immediate answers as to what their purpose was, the more everybody would freak out.

In building this climax, the film varies crucially from Chiang’s premise. Now Louise seems to alter the future. She apparently summons the will to induce General Shang, at a future celebration of the successful mission, to give her his private cellphone number and tell her his wife’s dying words. Back in the past, Louise uses this new knowledge to induce the General to hold his fire. All this is presented in a classical ticking-clock drama of suspense and pursuit.

The device is a bit awkward; instead of visiting an actual future, Louise seems present at one where the General, against all plausibility, tells her things she supposedly already knows. And how she induces him to spill all this is unclear, at least to me. The climax also breaks with the original story’s idea that Louise doesn’t exercise free will but accepts her role in the course of time.

More often than one might expect, classically constructed films break some of their self-imposed rules in the rush to a climax. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is one of my favorite examples, in which the climax violates the story’s method of pod-cloning. Sometimes an exciting denouement or a shocking twist tends to make us forget not only plausibility but also the premises that have operated over the previous ninety minutes.

An unsympathetic critic could object to the injection of a chase, a deadline, and a last-minute salvation of the mission, as well as the one-world moral of the movie. But to enjoy Hollywood, as with enjoying friends and other aspects of life, you have to accept, and even come to enjoy, the flaws too. The center of the film remains our transmutation of sympathy for a grieving mother into sympathy for a woman who knows she will be grieving for a child yet unborn, and yet embraces her destiny. The formal strategies serve to vividly convey this reversal of feeling, in the process ennobling a character reconciled to the transient joys of life.

Kenneth Burke once characterized literary form as “the psychology of the audience.” Filmmakers, like all artists, have recognized this from almost the beginning, but it may seem that today’s creative community is more self-conscious than ever before. If “form is the new content,” as I’ve suggested before, it’s a welcome development. Filmmakers are exploring lots of possibilities for engaging our minds and emotions, while still striving to keep their stories understandable to a large audience. Arrival could not have been made in my sacred 1940s, but its deft innovations build upon a foundation that was laid then.

Thanks to conversations with Jeff Smith and Kristin about Arrival. Thanks also to Merijoy Endrizzi-Ray and Jacob Rust at Madison’s Sundance Theater.

Jeff Goldsmith has an enlightening interview with Eric Hisserer at Screencraft. Ted Chiang’s novella is in the collection Stories of Your Life and Others. Burke’s discussion is in the essay, “Psychology and Form.”

The first quarter of Le Carré’s Our Kind of Traitor consists of an “intercut” sequence between past events and present interrogation that, in its free use of tenses, time tags, and other devices, seems to aim at a literary equivalent of the Russia House film opening. A pity that the recent film of Our Kind of Traitor didn’t try for a cinematic equivalent.

For more on modern treatments of narration and plot structure, try here. For further discussions of 1940s treatments of time-juggling, here are some blog entries.

P.S. 3 December 2016: The original entry didn’t use Minority Report or It Happened Tomorrow as examples of averting the future. They’re corrections to my original mention of Don’t Look Now, which was not an accurate example. David Cairns wrote to remind me of that, and to point out that the glimpse of the future we get in that film is in an interesting way akin to what we get in Arrival, and I hadn’t noticed that. For those who haven’t seen Don’t Look Now, I won’t add to an already spoiler-heavy entry. I’ll simply thank David, whose exemplary blogsite Shadowplay (currently hosting a blogathon under the rubric of The Late Show) is a must for every film lover. His new film, The Northleach Horror, is nearing completion; details here.

Arrival (2016).

Silents nights: Stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings, the sequel

Kristin here:

A welcome translation, long awaited

From 1991 to 2003, the University of Wisconsin Press published an even dozen books of cinema history in the series Wisconsin Studies in Film. The editorial board consisted of David Bordwell, Donald Crafton, and Vance Kepley, with me as supervising editor. In a little over a decade, we accomplished our simple goal of fostering excellent historical studies in an era when it was far less easy to get such books published than it is now.

Among the dozen was Film Essays and Criticism, a volume of previously untranslated reviews and essays by Rudolf Arnheim (1997). That volume was made possible by the dedication of Brenda Benthien, its translator. Now Brenda has pursued a project she and I discussed long ago. She has brought to fruition a translation of the important classic book, Rudolf Kurtz’s 1926 Expressionismus und Film.

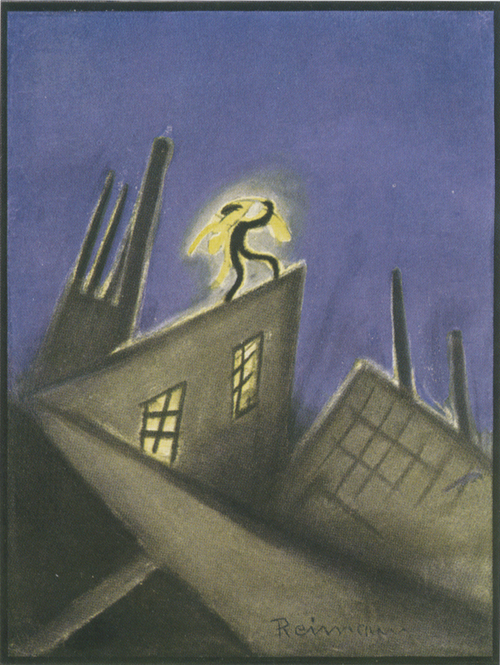

Kurtz’s book has been important enough to warrant two reprint editions in German, one in 1965 by Verlag Hans Rohr, with the illustrations all in black and white and the original cover painting by Paul Leni not used, and another in 2007 by Taschen, edited and with a lengthy essay by Christian Kiening and Ulrich Johannes Beil, as well as the original color illustrations and cover. The English translation, published earlier this year by John Libbey, essentially replicates the 2007 edition, including the cover design and the Kiening/Beil essay. The color illustrations, such as the frontispiece, a design by Walter Reimann for Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (top), are also reproduced.

Kiening and Beil are listed as editors here as well. As they point out in their brief introduction to the English edition, there had already been translations into French and Italian, but without the illustrations. Our English version may be late, but it comes much closer to replicating Kurtz’s original.

Kurtz’s title sums up his approach. He defines Expressionism in relation to the other arts of the era, particularly painting and theatre, and discusses the style of six films. Of these, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Waxworks are familiar; From Morn to Midnight, Genuine, and Raskolnikow less so; and The House on the Moon is still, as far as I know, completely lost. (An excellent DVD of Von Morgens bis Mitternacht is available from the FilmMuseum via the link. The Alpha editions of Genuine and Raskonikow are, by report, American cut-down versions with poor visuals.)

One benefit of consulting the original or Benthien’s translation is to reveal that Siegfried Kracauer distorted the famous quotation from designer Hermann Warm that he includes in From Caligari to Hitler: “Films must be drawings brought to life” (p. 68). The original, “Das Filmbild muss Graphik werden” (p. 66 of Expressionismus und Film) is more accurately rendered by Benthien as “The filmed image must become graphic art” (p. 68). “Graphic art,” after all, includes far more than drawings.

The Kiening and Beil essay mentioned above is included in the translation. It is a substantial piece, taking up 75 pages of the book’s total of 214. The authors explain Kurtz’s background in the art world and film industry of the era, as well as discussing conceptions of Expressionism in the years leading up to the release of Caligari. They cite many contemporary theorists’ and critics’s views of of Expressionism in the cinema. Kiening and Beil flesh out Kurtz’s work by pointing out several Expressionist or semi-Expressionist films that Kurtz doesn’t mention. They explain how From Caligari to Hitler and (slightly later) Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen became popular as explications of Expressionist cinema, leaving Kurtz in relative obscurity until recent decades. In short, the essay, entitled simply “Afterword,” is an erudite and invaluable addition to this edition of Kurtz’s book.

Cinematic after all

Way back in 1969, when I was taking my first film class, I saw The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and became fascinated with German silent cinema, especially the Expressionist movement. I still retain a surprising willingness to sit through German films of the era–even mediocre ones–with their slow pace and heavy acting. Back in those early days, I tried to see the German classics, many of which were available in poor 8mm and 16mm copies.

I vaguely remember being disappointed by my first viewing of The Student of Prague. At the time of that viewing, film studies were still in their early days, and just about everyone assumed that a film was “cinematic” if it had quite a bit of editing and camera movement. The Student of Prague, like many films of its era, was short on both. Its long-take opening shot, with no cut-ins or tracking camera, seemed the epitome of stagy cinema.

I don’t know which version of the film I saw, but it wasn’t the original 1913 one. The film has a complicated history of re-editing and re-release, both theatrically and for home video. This history is recounted in the booklet accompanying the Munich Filmmuseum’s new DVD release of a reconstructed version approximating the 1913 release print, as well as the much shorter American release print. The original version was sold to a producer, Robert Glombeck, who exploited the occasion of the 1926 remake to release the original, highly reworked, including the addition of 107 intertitles. (The original had deliberately been made using a minimal number of intertitles.) Although shortened American and Japanese release prints of the 1913 version survived, the original German one did not.

The new reconstruction has been made from the Glombeck negative, as well as the other release prints, a script, and the incomplete censor’s record. While it cannot claim to be an exact replica of the original, it is far closer than we have had up to now. The excessive intertitles have been removed and a prologue shot showing scriptwriter Hanns Heinz Ewers and lead actor Paul Wegener looking up at Prague Castle restored. (It survived only in the American print.)

Even before this new release, I had gained a far greater respect for this supposedly uncinematic film. My first viewing came before academic interest in early film blossomed with events like The Brighton Project in 1978, trends like the spread of film archives and the rediscovery of many lost prints, and a general recognition of the historical, entertainment, and aesthetic value of early films, even among the general public. Gradually historians had realized that editing and camera movement were not the only techniques that exploited the techniques of the medium. There were long takes and intricate staging. There was the compositional exploitation of depth and the surprises of offscreen space. During the period 1992 to 1998, Yuri Tsivian, Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster, David, and I explored various techniques that cinema of the 1910s used for expressive purposes. (See the codicil for citations.)

In 1993 I gave a keynote address at the fifteenth IAMHIST conference, “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity, 1913-1919,” at the University of Amsterdam. In it I discussed a wide range techniques of framing, staging, acting, and unusual editing that were innovated in films made in many countries, all tending to enhance expressivity. Among my examples was that opening scene of The Student of Prague. I said, “This seems to me a case that could be dismissed as primitive. Yet it could also be described as a complexly staged scene that sets up the basic narrative situation and uses depth and unexpected appearances from off-screen to heighten the impact of the action.”

Now that we have something approximating the original version, we can look again at that first shot. There are two presentations of the reconstruction in this set, one with a piano rendition of the original score, which survives only in a printed piano score, and one with an orchestration of that score. The piano version runs distinctly shorter, and it looks to be projected at about the right rate. In this presentation, the first shot runs 3 minutes 40 seconds. It contains only two intertitles. After an establishing shot of a beer-garden, our hero enters, and the students hail him as the best fencer among them. This is information that we could only learn through speech. The title also provides his name, Balduin.

He sits glumly, largely ignoring the action behind him as Lydushka (apparently secretly in love with Balduin) enters and the students lift her onto a table for a dance. As this ends, a coach suddenly drives in from the left, and as it blocks most of the background, the students swiftly exit.

Scapinelli gets out of the coach and joins Balduin, tapping him slyly on the shoulder as Lydushka watches, growing anxious as the two start a conversation. The second intertitle provides crucial plot information, as Balduin announces that he is ruined and needs either a winning lottery ticket or a rich heiress. Scapinelli leads him out, the camera reframing slightly with them and with Lydusha, who moves forward to watch them. Soon Scapinelli will appear in Balduin’s room and make the fateful bargain, providing riches and the heiress in exchange for his mirror image.

There is nothing quite like this shot in the rest of the film, but there are some very impressive depth shots. These typically involve a character in the foreground or background looking at other characters. Such shots substitute for eyeline-match cutting, which was not yet a convention of German cinema. In the shot at the bottom of this entry, Lydushka spies on a romantic scene between Balduin and Countess Margit. Below, Balduin realizes that his Doppelganger has killed Margit’s fiancé in a duel, thereby disgracing him.

And there are, of course, the extraordinary shots of Balduin together with his Doppelgänger , achieved by the great German cinematographer, Guido Seeber. When the double, on the right, confronts the lovers in the old Jewish cemetery, the careful staging and double exposure allow Balduin to cross behind the large tombstone and enter the space where his nemesis has been moments before (see the top of this section).

Apart from the different versions of The Student of Prague, the DVD set contains a 1913 short, Die ideale Gattin (“The Ideal Wife”), also “made by” Hanns Heinz Ewers. (The edition treats Ewers as the main creator of The Student of Prague, though most sources credit Stellan Rye as the director. It is true that at the time the scriptwriter was considered the creator of a film, but there’s no clarification of this in the notes.)

This is a charming little comedy starring Paul Biensfeldt as the hero oppressed by his strict, humorless female relatives and in search of a perpetually-smiling wife. Biensfeldt is a familiar face if not name, having played roles in several of Lubitsch’s German features, such as Menon in Das Weib des Pharao. Lubitsch himself plays a small role here, appearing as the matchmaker in only one scene. He is unrecognizable under a wig and beard and has nothing little to do.

The DVDs can be ordered directly from the Edition Filmmuseum shop. I note that Filmmuseum editions are now being sold on Amazon.de as well.

No buffalo were harmed in the making of this film

In March we praised the rescue of a major documentary, Strange Victory, released by Amy Heller and Dennis Doros’ Milestone Film & Video. The company has since brought out a film long thought to be lost, The Daughter of Dawn, one of a handful of fiction features from the decade that used casts entirely made up of Native Americans. (Notable others are Hiawatha [1913], In the Land of the Headhunters [1914], The Vanishing Race [1917], and Before the White Man Came [1920].)

As often happens in such cases, the director of The Daughter of Dawn, Norbert A. Myles, was a white man. He had started as an actor in 1913, directed three features in the 1920s, and went on to a long career working as a makeup artist (usually uncredited) on many of the most famous films of the 1930s and 1940s–most notably Ray Bolger’s makeup as the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz.

And as also often happens, the scenario avoids analyzing the culture of the ethnic group in question. The film largely falls back on a very conventional central premise. The film centers around a love rectangle, with the heroine, a Kiowa chief’s daughter nicknamed Daughter of Dawn, in love with the stalwart hunter White Eagle. Black Wolf, a rich brave seeking to become the new chief, spurns the devoted Red Wing and seeks permission to marry Daughter of the Dawn.

There are some action scenes, notably a chase after a herd of buffalo early on. We don’t see any actual killing of buffalo, and although the hunters return to their village announcing success, there is no glimpse of carcasses. Whether this was due to budgetary factors or legal or safety restrictions is unclear. A later battle scene between the Kiowas and some raiding Comanches is more successful. Myles wisely keeps his camera at a distance from most of the action, which creates a sense of genuine combat, unlike the effect of fake-looking close shots of two actors struggling hand to hand.

Still, most of the scenes are devoted to the romance plot, which is rather a pity.

The attraction of the film, though, is its authenticity. Not only did hundreds of Kiowas and Comanches perform for the camera, but they brought their own tipis, costumes, and accessories. They were by this point living on reservations but not so long that they had lost touch with their traditions. The period when the action is set is never specified, but there is no sign of white encroachment, no visible roads, and no mention of the threat of westward-moving pioneers or military. It is as close a look into this vanished past as we are ever likely to have. The Native Americans seem to have been happy to display their heirlooms for the camera, as in this scene where the heroine converses with her father in their tipi.

The performances of most of the cast are predictably rather stiff, with most of them primarily standing or moving where told to by the director. Dialogue titles rather than pantomime handle most of the story information. Myles successfully cast two more natural performers for his leads. Esther Le Barre and White Parker were Comanches (the tribe cast as the villains in the story) but played Kiowas, no doubt because they were both expressive and attractive–though to the filmmakers’ credit, they made no attempt to glamorize the pair.

In short, The Daughter of Dawn is an extraordinary historical document. For more information on the film’s making, rediscovery, and modern release, see the site of the institution that found the surviving print, the Oklahoma Historical Society. Its museum, by the way, has on display the historic tipi used in the film as the heroine’s dwelling. In 2013, after the film was preserved, the Library of Congress added it to the National Film Registry.

I discuss The Student of Prague‘s seminal role in establishing fantasy and horror as key genres that would remain important and culminate in the Expressionist films in “Im Amfang war … : Some Links between Germany Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920, Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli, eds. (Edizioni Biblioteca dell’Immagine, 1990): 138-148.

Yuri Tsivian concentrated on the introduction of mirrors into 1910s cinema to create a new way, nontheatrical way of presenting space to the spectator. See his “Portraits, Mirrors, Death: On Some Decadent Clichés in Early Russian Films,” Iris nos. 14-15 (Autumn 1992): 67-83. My 1993 keynote address quoted above was published as “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, eds. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995): 65-85. Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs focused on acting and staging in dept in their Theatre to Cinema (Oxford University Press, 1998). The revised edition is available online.

David began discussing tableau staging and compositions in depth in Chapter 6 of his On the History Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997) and continued the exploration in the Feuillade chapter of Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging (University of California Press, 2005). For entries relevant to German Expressionism, check our Ten Best lists and our entries on Homunculus, on Sappho and others, on INRI and others, and on Murnau before Nosferatu.

[November 22: Brenda informs me that she also did the intertitles for FilmMuseum DVD of The Student of Prague.]

The Student of Prague.

OBSERVATIONS goes all FILMSTRUCK

DB here:

In light of the cataclysm that struck on election day, to return to talking of films can seem frivolous. We’ve delayed posting this blog because we, like millions of other people, are seized with a dread as to what may come for our friends, our neighbors, our country and the world.

At least for the moment, though, we can’t stop living other aspects of our lives. Judging by the attention our entries continue to get in these days, we think that we should keep trying to provide ideas and information about film. Art is important too.

Thunderstruck by FilmStruck

You probably know that Turner Classic Movies has partnered with the Criterion Collection to create a streaming service called FilmStruck. There’s a comprehensive overview of the service on Variety, and Peter Becker has an invigorating introduction on the Criterion site.

The library includes many hundreds of films, mostly foreign imports and independent features and shorts. Many of the titles come from US non-studio distributors, but a vast number are from the Criterion library. Many will be titles not available on DVD.

It’s an all-you-can eat subscription service. For $6.99 per month you can get a basic membership in FilmStruck, and that will provide hundreds of titles, including many Criterion ones. For an extra $4, you can add on the Criterion Channel, with a huge additional selection (about 500 titles at any moment). There’s an annual rate covering both for $99. You can sign up for a 14-day free trial here.

Both wings of Filmstruck include the sort of bonus materials found on DVDs: background information, archival footage, talking heads, and video essays. The Criterion titles include voice-over commentary you can play while watching. I’m especially excited by the prospect of having the filmmakers’ commentaries from out-of-print laserdisc editions (e.g., Boogie Nights). And the FilmStruck site is already hosting, for free, a rich array of blog entries by experts (Pablo Kjolseth, Kimberly Lindbergs et al.) offering perspectives on the library titles.

The films can stand singly, but they’re also gathered into groups by theme, director, nation, or whatever.

The Criterion Collection is richly curated too, with new groupings and titles highlighted every day. There are even Friday night double features, and new releases constantly refreshing the pool. And there are special events, like an evening at Manhattan’s wonderful Metrograph theatre.

This double feature is introduced by Michael Sragow on the regular Criterion website, so the synergy is tight.

In addition, there are new introductions and appreciative discussions of films. For example, our friend Sean Axmaker has some coming up. And there are continuing series with film-struck partisans.

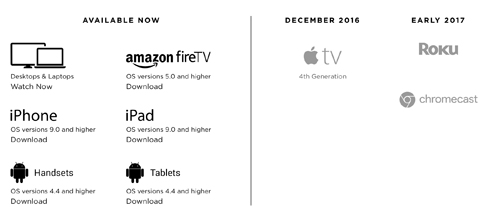

At present, FilmStruck can be streamed on any computer or laptop, Amazon Fire, recent generations of iPad, and other devices. But not on your iPhone, pleeze. Roku and Chromecast access are coming early next year.

In short, this is a treasure house for fans of classic foreign and American films. Some older Hollywood studio films are available (e.g., Brute Force from Criterion), but I bet more of the TCM library studio will migrate to the service. I’m itching for those beautiful Warner Archive items.

FilmStruck and us (and you, we hope)

We are honored and happy to be involved with FilmStruck. Under the blog rubric, “Observations on Film Art,” Kristin and I and Jeff Smith, our collaborator on Film Art have launched a series for the Criterion Channel. We offer short appreciations of particular films and filmmakers.

There’s a video introduction to the three of us…

… including some potentially embarrassing vintage images.

Here’s our first entry, featuring Jeff Smith.

Coming up are Kristin on Kiarostami, and me on L’Avventura and Sanshiro Sugata. We hope to post about one per month.

Our discussions are analytical, focusing on particular techniques of style and narrative. They don’t contain crucial spoilers, so most can be watched before the film as well as after.

Of course we’re tremendously excited to get our ideas out there in a new platform. We conceive the series as like our blog—applying our research into film form, style, and history to films in a user-friendly way. We hope that we’ll find an audience among cinephiles as well as among more casual viewers who simply want to get more out of the films they see.

As the installments go online, we hope to post blog entries that flesh them out. Jeff will soon be posting an entry that supplements his Foreign Correspondent analysis.

My email address is still visible on every page of this site, so if you have responses to the FilmStruck versions of “Observations on Film Art,” we’d welcome hearing them. We look forward to working with our colleagues at Criterion—Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Tara Young, Penelope Bartlett, and all their associates. This ought to be plenty fun.

Thanks to Mary Huelsbeck and Amy Sloper of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research for letting us prowl the premises for our introductory video.

At Stream on Demand, Sean Axmaker reviews the FilmStruck project.

P.S. 15 November: Peter Becker talks with Scott Macaulay of Filmmaker about the ambitions of the Criterion Channel, with many details about films and filmmakers to be showcased.