Back on the trail of THE CHASE

Tuesday | November 1, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

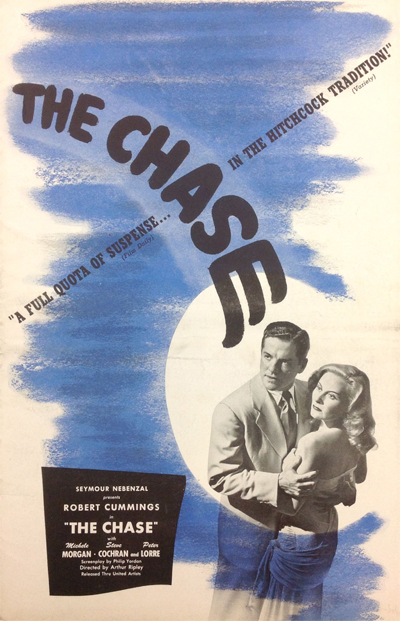

How did The Chase (1946) come to be such a weird movie?

Exploring that question in an August entry, I complained: “I haven’t located any scripts, alas.” I was forced to use what evidence I could muster from trade papers and the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Now I’ve learned of one screenplay for the film, and it confirms my primary conjectures—while offering some other complications. (What else is new?) You may want to return to that earlier entry before moving on with this, but this can stand on its own. Of course there are many spoilers ahead.

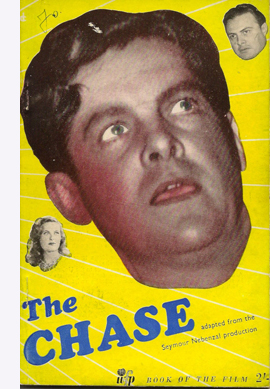

The screenplay is signed by Philip Yordan and dated 17 April 1946, with some inserted pages dated 16 May. It is held in the collection of the producer, Seymour Nebenzal, housed at the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Droessler and Christoph Michel supplied information about this document, and Miriam Landwehr produced a detailed synopsis and a comparison to the finished film. I’m very grateful to them for their assistance.

When is a dream not a dream?

The problem of the film as we have it is its And-then-I-woke-up plot. Navy veteran Chuck Scott takes a job as a chauffeur to Eddie Roman, who runs a smuggling racket with his henchman Gino. Roman’s wife Lorna longs to escape the marriage and induces Chuck to buy her passage on a ship bound for Cuba. Chuck, infatuated, flees with her, but in Havana she is killed in a nightclub and Chuck is the prime suspect.

Escaping from the cops, Chuck is killed by Gino, who has trailed the couple to Cuba. And now Chuck wakes up. We realize that the escape to Havana has been a dream that he’s had on the night he and Lorna were to sail. This rupture in the story action has been a crux for the film’s many admirers—a sheer piece of noir bravado.

Unfortunately, the dream has triggered Chuck’s old war trauma and he has amnesia. He can’t recall anything of the Miami episode. He returns to his doctor, who helps him recover his memory, rescue Lorna, and actually set out for Cuba with her. The film ends with the two in a carriage outside the nightclub that they visited in Chuck’s dream. This too has aroused a lot of comment; how could they visit in reality what Chuck only imagined?

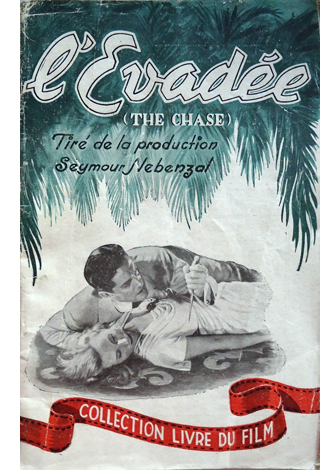

These and other anomalies in the film, along with a 1946 remark by Nebenzal about eliminating the screenplay’s “flashback,” led me to look into the production. Crucial as well were Cornell Woolrich’s original novel, The Black Path of Fear, and an anonymous novelization of the film published in Movie Mystery Magazine (December—January 1946). Since novelizations were often written on the basis of scripts, I inferred that aspects of the screenplay might have been preserved in that publication.

These and other anomalies in the film, along with a 1946 remark by Nebenzal about eliminating the screenplay’s “flashback,” led me to look into the production. Crucial as well were Cornell Woolrich’s original novel, The Black Path of Fear, and an anonymous novelization of the film published in Movie Mystery Magazine (December—January 1946). Since novelizations were often written on the basis of scripts, I inferred that aspects of the screenplay might have been preserved in that publication.

The original novel begins in Havana, where Lorna dies in the nightclub. Fleeing the police, Chuck tells Midnight, a woman who hides him, of how he met Lorna and Eddie Roman in Miami. At the end of this flashback, he sets out across Havana to find Lorna’s killer.

The central production decision, evidently taken by Nebenzal early on, was that in the film Lorna was to live and unite romantically with Chuck. How to keep Lorna alive and yet retain the dramatic murder and Chuck’s flight from the law?

Yordan’s screenplay, fairly closely followed by the novelization, adhered to Woolrich’s opening by starting with the Havana murder and letting Chuck recount the Miami backstory to Midnight. But then, on the trail of Lorna’s killer, the screenplay has Chuck killed by Gino. Then Chuck wakes up. We realize that the entire first part of the film—running an hour or so—has been his dream. So Lorna is kept alive for a genuine partnering and flight with Chuck.

The screenplay’s problem is that Chuck has dreamed not only the imaginary murder but everything leading up to it. What he tells Midnight in his dream includes all the veridical backstory of his becoming Roman’s chauffeur, learning of Lorna’s desire to escape, and fleeing with her. The dream, false in its Cuban sections, is faithful to actuality in most of its Miami stretch—the flashback that novel included and that Yordan retained.

That Miami backstory was the flashback that Nebenzal eliminated late in production, claiming that he felt there were too many flashback movies in release. He shifted the Miami scenes to the front of the movie, where they serve as conventional chronological action, and made the Midnight encounter in Chuck’s dream a straightforward scene in which she helps him evade the police.

Not quite rounded with a sleep

The screenplay and the novelization fool us by eliminating the dream’s “front frame.” There’s no scene showing Chuck going to sleep; we’re immediately in his imaginary Havana. By contrast, contemporaneous films using the dream device supplied at least a minimal setup. The Woman in the Window (1944), The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945), and Strange Impersonation (released April 1946) each include an innocuous piece of action that, in retrospect, indicates that the protagonist has fallen asleep and dreamed what we’ve just seen. The return to those setup situations tips us off that we’ve just seen a dream.

Evidently Yordan wanted to take this trend further by lopping off the setup altogether and plunging us straight into a dreamscape for a very long stretch. By killing the protagonist, Yordan supplied a shock that, given Hollywood conventions, would have to be recouped somehow. The dream device does that, bringing both hero and heroine back to life.

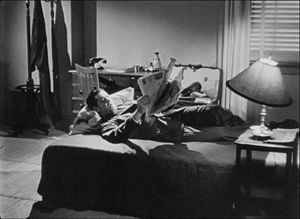

Once the flashback was shifted to the front of the film, however, Nebenzal needed a more conventional front frame to bracket off the dreamed escape to Cuba. Therefore he supplied a scene showing Chuck lying down just before he and Lorna are to flee. This scene is not in the screenplay or the novelization.

As in other films of the time, the setup is equivocal. Chuck lies down and reads a newspaper and just barely starts to yawn as the film fades out. Cunningly, as I pointed out in the earlier entry, there’s a bridge of diegetic music—the piano concerto that Roman is listening to on the phonograph—and we then see Roman and Gino in the living room. A more typical dream film would remain attached to the dreamer; we might see Chuck get up from the bed, close his suitcase, and sneak out with Lorna. Instead, we’re with Gino when he goes to Chuck’s room, finds him gone, and reports his departure to a curiously listless Roman. So Chuck dreams Gino’s discovery of his departure. The shift to Roman and Gino seems to corroborate the objectivity of what’s happening, especially because the film’s non-dream stretches have freely intercut Chuck’s actions with those of his boss.

In the earlier entry I pointed out some visual anomalies among the framing scene, the scene of Gino visiting Chuck’s room, and the waking-up scene. Changes in props suggest that the retakes to which Nebenzal alluded in a memo in August may have included shooting the setup frame. By mid-September he was announcing that he had abandoned the flashback, and the film was completed by 7 October.

For those of a fussbudget inclination, like me, you can find hints that the original waking-up scene was modified to fit the front frame that was added later. Here’s the waking-up framing shot, which tracks back from the ringing telephone.

The lighting, setting, and camera angle closely match what we realize in retrospect was the setup of Chuck falling asleep.

But the closer views of Chuck woozily coming out of his dream vary from neighboring shots in tonality and in the position of the chair behind him. (In the master shot it’s angled to our right, but in this and other shots it’s angled to the left.)

Later shots in the waking-up scene show different positions of other props. While the chair remains angled to the left, the lampshade (tipped in the earlier establishing shots) is upright now; there’s no longer a magazine behind the lamp; and the water carafe and pills on the desk are in a slightly different array.

In addition, the lighting scheme is somewhat different; the interior of Chuck’s suitcase is blown to pale gray in the framing shots but in the ones above it’s far darker. And the coat and coatrack visible on frame left of the dream frame aren’t visible in the widest shot we get later in the scene, the second one above.

I know: Picky, picky. We could put these disparities down to routine continuity errors. But their patterned differences are consistent with their being part of a patchwork. It seems plausible that most of the waking-up scene was shot during principal photography, but the opening shot of that scene, along with the falling-asleep frame that was added, was filmed during the retakes that Nebenzal oversaw in August and September.

Cabin fever

One of the weirdest aspects of the film we have is the ending. Eddie Roman and Gino, racing to stop Chuck and Lorna from escaping, smash into a locomotive. This chase is intercut with Chuck and Lorna in a ship’s cabin waiting to sail off. The problem is that, for censorship reasons, this unmarried couple can’t easily be shown running off together, and sharing the same quarters at that.

Several commentators have noted that the set recalls the one that Chuck dreams (below, left).

The cabins aren’t all that much alike, though the clock on the back wall probably pops out as a reminder. Yordan’s script asks that the second cabin suggest the first one.

This set should be basically the same as the set used before yet there must be distinct differences.

It seems that Yordan wanted to hint that Chuck’s dream was a sort of premonition of the trip they’d wind up taking. The dialogue flirts with the possibility. As Lorna says, “For once in my life I wish I could want something that was good for me,” the screenplay goes on:

At this point, something happens to Chuck. He becomes aware that he has heard this line before. Suddenly he knows everything that she is going to say, everything that’s in her heart.

When he suggests she tries to recover her lost innocence, she asks: “You haven’t been drinking, have you?” he replies: “No–just dreaming.”

He adds that he’s dreaming “what a chauffeur’s not supposed to dream about.” Wanting to give her freedom, he decides not to go to Cuba with her and vows to reenlist in the service. They don’t embrace. Quick dissolve to Chuck marching in a military parade down Fifth Avenue. His decision not to have a runaway romance is rewarded by the sight of Lorna, now his wife, cheering him from the sidewalk. It’s on this burst of patriotism that the screenplay ends.

Was this preposterous epilogue ever shot? Had it been jettisoned by the start of production on 16 May, presumably the 14 April script wouldn’t have included it (since it includes some revisions dated 16 May). But the parade isn’t in the novelization, which is otherwise very faithful to the April script. The novelization was based on a script sent to the magazine in late June or early July, so perhaps the parade was dropped after principal photography began. We do know that in September Nebenzal was shooting alternative endings.

The novelization’s cabin scene follows the screenplay’s tack, indicating that Chuck’s “dream” of union with Lorna should end with the couple splitting up. But she resists his suggestion, and things take a familiar turn.

And in the next instant, Chuck’s mouth found her warm lips, shutting off her words, his arms pressing her to him crushingly.

This burst of passion is interrupted by a telegram from Dr. Davidson telling Chuck of Eddie’s death. The message asks the couple to return, in a wry phrasing: “Before you get into any real trouble in Havana.” This version concludes with them agreeing to get off the ship and get married, so they never sail for Havana. No parade finale here.

The film’s last moments, as any aficionado knows, are something else again. The scene in the cabin is played eerily, with Chuck striding in and glancing at a newspaper he’s carrying. When she asks when the boat will get started, he says, “It doesn’t matter now.” Did the newspaper carry news of Roman’s crash? (Unlikely, so soon.) And why doesn’t he take Lorna in his arms, for the clinch and fade-out? Did the production team not have the footage, after shooting the lead-in to the parade?

The film’s epilogue, absent from both the script and the novelization, casts aside any concern about whether this furtive couple has married or not. We’re back in front of the La Habana club, with Chuck and Lorna in the carriage declaring their love for one another.

This scene (below left), as I suggested in the August entry, is quarried out of footage shot for Chuck’s dream (below right), right down to the grumpy driver.

The result is pretty Buñuelian. You can call it a reenactment of the dream in real life. Or you can say that it plunges us back into Chuck’s dream–leaving the shipboard resolution suspended. In their haste to wrap things up, Nebenzal and his director Arthur Ripley give us the conventional clinch, all right, but with a screwball spin.

So my conjecture about the original ordering of the film’s plot is borne out by the discovery of the screenplay. But we still don’t know why the film, once the parade epilogue was jettisoned, doesn’t include the clinch in the cabin and the resolution to marry. Both were in the novelization. Why go back to the Habana club and the recycled footage? Only further research into other production documents can tell us for sure. In the meantime, we’re left with another Forties film that flaunts the unexpected virtues of accidental innovation.

The Chase was restored by UCLA and is available on a handsome Blu-ray edition from Kino Lorber. My references to production materials and press releases for the film come from the sources listed in the earlier entry. One of my illustrations above comes from a French novelization that I haven’t yet found; I assume that it’s a translation of the English one, but maybe not.

This isn’t the first time I’ve returned to fuss over an earlier entry. I did it with The Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here and here) and twice with Hitchcock’s ideas of suspense (here and here). If I keep trying, maybe I’ll get it right.

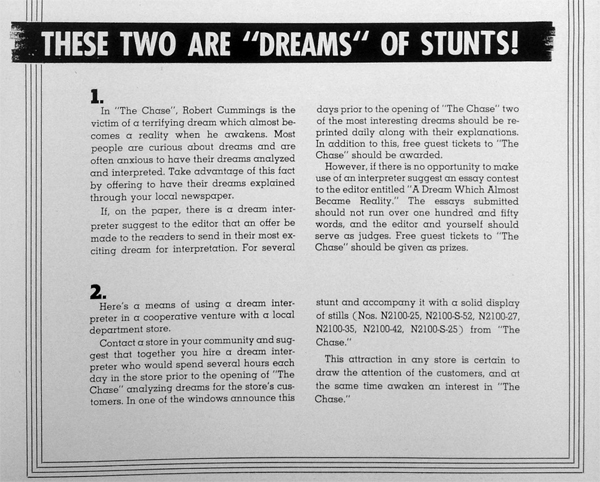

Surprisingly, the dream device was built into the studio’s publicity to a small extent. (See images below.)

P.S. 2 November 2016: David Koepp, film noir aficionado, adroit screenwriter and director, and one of the People We Like, writes:

I love your blog post on The Chase. Just read it, and, coincidentally, I just watched The Chase yesterday and had been meaning to e-mail you about it. You’ve said pretty much all there is to say about that movie already (and with your customary thoughtfulness), but just two things I wanted to add.

First, this film stretches the kind phrase “bold use of coincidence” to new extremes. There is seemingly NO situation that they weren’t comfortable having resolved, furthered, or complicated by coincidence, and in a strange way I kind of came to appreciate that. I mean, it’s economical, if nothing else.

But my second thing is more interesting. It’s funny that you focus today on the falling-asleep framing device for the dream sequence, because I had an observation in that very spot, a curious bit of staging which I didn’t fully understand, but now I think I do thanks to your post. After the master shot pulls back from the phone, Robert Cummings goes to the bed and does the strangest thing. He picks up the pillow, tosses it to the foot of the bed, and lays down on the bed for his fateful nap, WITH HIS SHOES ON. Think about that — he picks up the pillow from the socially agreed-upon head of the bed, tosses it to the foot of the bed, and then lies down with his dirty shoes on the now-unprotected sheet at the head of the bed. Who in God’s name would do that?

Only one person I can think of — an actor who’s been asked by the director to do it to protect the composition. In its widest position, the lamp in the right foreground blocks the head of the bed and the remainder of the set to the right, and the master shot plays beautifully as one long pullback. So, at first I figured the director just liked his master and asked the actor to toss the pillow to the foot of the bed, i.e., “I know it’s weird, Bob, but would you mind?, it’s a lovely shot and I don’t want to have to break it up and turn around to shoot you at the head of the bed.”

But there’s another possible reason, if your reshoot theory is correct. Which is that they were rushing to squeeze in a clarifying reshoot, struggling to recreate the set and props as they were in the original footage, and they didn’t want/didn’t have time to/couldn’t afford to rebuild the other walls of the set to accommodate. Plus there’s a door in the wall to camera right, and a hallway outside it with a return. More stuff to build–way too expensive and time-consuming for the hurry-up-and-grab-this approach they’d need for a reshoot with the studio and the release date breathing down their necks.

Maybe? Who knows! But it’s fun to speculate.

It’s interesting that in the April screenplay, Yordan doesn’t specify that Chuck is sleeping at the foot of his bed. We simply have: “Chuck lying on his cot, fully dressed in his chauffeur’s uniform.” David’s point is persuasive to me. It would be harder to compose a pull-back from the phone (a gradual revelation that Yordan’s screenplay insists on) if Chuck were lying at the head of the bed. The awakened shots not made during the reshoots also have Chuck sleeping at the foot of the bed, but David’s point about the composition makes sense for those too.

David’s mention of Chuck’s position makes me think about something else. Lying at the foot of the bed also suggests, to me at least, an intention of not going to sleep but rather just relaxing. Had Chuck stretched out on the bed normally, might we be more inclined to suspect a dream was coming on?

Thanks to David for sharing the practical filmmaker’s perspective! Now more than ever I’d like to see the daily set reports for this movie.

P.P.P. 13 November 2016: For hardcore fans only: At the suggestion of Soren Schoff, a local friend, I obtained a copy of the UK novelization of The Chase, published by Hollywood Publications of London in 1947. It’s signed by Kit Porlock, a name one sees on many novelizations published in London in the Forties. This text is quite different from the Movie Mystery Magazine edition, and it adheres closely to the finished film. But there are interesting aspects to it.

Like the movie, it starts with Chuck in Miami and follows him through the romance with Lorna. The front end of the dream frame, just before he’s about to run off with Lorna, is given more explicitly than in the film:

Like the movie, it starts with Chuck in Miami and follows him through the romance with Lorna. The front end of the dream frame, just before he’s about to run off with Lorna, is given more explicitly than in the film:

He stretched out on the divan for a while. He had nothing to do for the next four or five hours. A nap would be sensible if only he could get to sleep.

He took a couple of his pills and tried to relax. It was no good. Too many images and fancies revolved in his brain. He readjusted the pillow under his head and sprawled out luxuriously Just to have an hour or so would do him the world of good. . . . .

This ends a chapter. The next chapter begins with Gino entering and finding Chuck gone, more or less as in the film.

When Chuck comes out of the Havana dream, the novelization likewise makes sure we know it wasn’t real (“All that was so vivid to him had only been a dream!”). But the amnesia has kicked in and so Chuck has to seek help from Dr. Davidson, as in the film.

There are two only other major differences from the finished film. For one thing, like the US adaptation, the UK one ends with Lorna and Chuck in the ship’s cabin. Here it’s clear that the ship has delayed departure long enough for a newspaper edition to arrive and announce the deaths of Roman and Gino in the car crash. In the film, Chuck simply comes in with a folded newspaper, and we aren’t explicitly told why he now thinks the two of them are safe. Maybe the final release just dropped his act of showing her the news item.

The second difference from the film is that, like the MMM version, the story ends in the cabin with the couple united in love. There’s no epilogue in the carriage outside the La Habana club. This novelization, said to be “from the original film script,” isn’t, but perhaps it’s based on a rewrite that was closer to the final release–that is, after Nebenzal had shifted the flashback to the front of the plot and had jettisoned the military-parade finale. But we still have to wonder why the final cabin clinch in both novelizations isn’t there in the film, and why the carriage scene isn’t in either novelization. The Chase remains elusive.

The Chase (1946) United Artists pressbook.