Archive for November 2016

Murnau before NOSFERATU

Der Gang in die Nacht (The Dark Road, 1921).

DB here:

For many decades, The Last Laugh (Der Letze Mann,1924) was the F. W. Murnau film. If you were a film buff in the fifties or sixties, that staple of film societies and college courses was probably the first Murnau you saw. Eventually you got to those French favorites, Sunrise (1927) and Tabu (1931). Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (19226) came along in there somewhere. Tartuffe (1926), great as it is, has always seemed a specialized taste.

Today, I think, Nosferatu is probably the one everyone sees first. It fits the modern taste for horror movies, and it is genuinely scary. It popped up in music videos, got remade by Herzog, and will be forever remembered for the vampire’s spindly, ratlike silhouette and the wholly fitting name of the performer, Max Schreck.

Eventually Murnau aficionados caught up with lesser-known Burning Soil (Der brennende Acker, 1922), Phantom (1922), and The Finances of the Grand Duke (Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs, 1923), the latter two available on good DVD versions. But what about Murnau’s very earliest films?

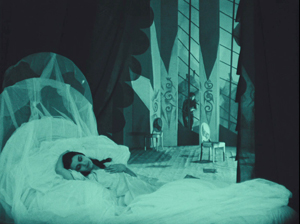

Of the nine films he made before Nosferatu, only two survive more or less complete. They circulated in unsatisfactory condition for many years, but Schloss Vogelöd (The Haunted Castle, 1921), which Murnau made just before Nosferatu, eventually emerged in a splendid restoration based on original negative material. Now we have a digital restoration of Murnau’s earliest surviving film, his seventh: Der Gang in die Nacht (The Dark Road, or “Path into Darkness,” 1921).

And what a restoration it is! The Munich Film Museum’s team has created one of the most beautiful editions of a silent film I’ve ever seen. They started with four reels of camera negative, then carefully integrated material from other sources. Thanks to digital manipulation, I couldn’t tell where the alien footage was.

You look at these shots and realize that most versions of silent films are deeply unfaithful to what early audiences saw. Compare a shot from the lamentable YouTube bootleg and a shot from this version. The smallness of the YouTube image here improves it; blow it up on a big monitor and it goes horribly blotchy.

In those days, the camera negative was usually the printing negative, so what was recorded got onto the screen. The new Munich restoration allows you to see everything in the frame, with a marvelous translucence and density of detail. It will project fine big. Forget High Frame Rate: This is hypnotic, immersive cinema.

Der Gang in die Nacht will be shown in the Museum of Modern Art’s “To Save and Protect” series on 13 and 14 November. If you can get there, you should go! If not, we can hope that the film will soon appear on DVD. Remember DVDs?

Silents, golden

The canonized classics of Expressionist cinema, from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari onward, are superb films, no doubt. But there are lots of other major movies from the period. The German industry flourished during World War I, and even the postwar inflation encouraged a burst of moviemaking. Hundreds of films were produced every year. I’m no expert, but of the seventy or so I’ve seen nearly all are fascinating and surprising. From the brute force of Der Tunnel (1915) and the demented monumentality of Homunculus (1916) to the weirdness of Algol and I.N.R.I. (both 1920), the peculiar pleasures of Sappho (1921) and the splendors of The Nibelungen (1924), I’ve been captivated by this cinema. Caligari is merely the dark and spiky tip of a mighty iceberg.

Der Gang in die Nacht is derived from a screenplay by the Danish scenarist Harriet Bloch. It’s an example of the “nobility film,” a genre cultivated by the Nordisk studio where Bloch worked. In these stories, an upper-class man becomes obsessed with a working-class woman, and she leads him to disaster. The most famous “nobility film” of the era is Dreyer’s The President (1919), when the genre was already somewhat old hat.

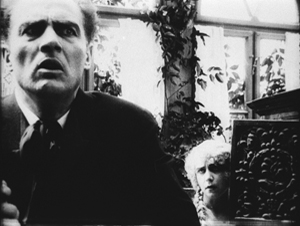

In Murnau’s film, the well-to-do protagonist is Dr. Eigil Börne. Uneasy with his courtship of his wispy fiancée Helene, he plunges into an affair with the dancer Lily. They move to a seaside cottage, where their idyll is interrupted by the spectral figure of a blind artist. (Regrettably, we never get a glimpse of his paintings.) The Painter is played in nearly full Cesare mode by Conrad Veidt: drifting through the landscape and clutching at the air. After Dr. Börne restores the Painter’s sight, Lily falls in love with him and leaves Börne. Unhappiness ensues for all, and yes, suicide is involved.

With only four delineated characters, the plot’s emphasis falls on their reactions to each others’ changing feelings. It’s a surprisingly unsensational melodrama, with no blackmail, threats of murder, or guilty secrets. It’s just about people’s emotional attachments waning, often for reasons they don’t understand. The drama of shifting, elusive moods looks fairly modern.

The playing is deliberate, with a range of acting styles. The drooping Helene, the skittish Lily, the somnambulistic Painter, and the raging Börne may seem to come in from four different movies. But Börne is on a knife-edge from the start, when he nervously leaves Helene. He broods fiercely during his night at the theatre, well before he succumbs to Lily’s charm. Like Scotty in Vertigo, he’s ready to fall. And as a complacent bourgeois, he doesn’t grasp the romantic fascination projected by the passive, wraithlike Painter. Nor is Lily merely flighty and treacherous. The Painter seems to stir her to a genuine love very different from her flirty seduction of the doctor. Helene, mournful throughout all this, is last seen in her sickbed stroking a newspaper photograph of Börne.

The concentration on four characters, each trembling with uncertainty, and the meshing of their moods with the stormy seaside, suggested to one observer an analogy with current stagecraft.

Here for the first time filmmakers try to incorporate the Kammerspiel [chamber play] into a film play. A strong, affecting plot with only a handful of characters has been developed through the smallest psychological details, the unity of locale and characters, the intimate interweaving of the atmospheric mood and the characters’ emotional life. All this has been achieved with the most sophisticated use of facial expression and cinematic direction.

1921 is usually taken as the year that the Kammerspiel genre began, with Scherben (Shattered) and Hintertreppe (Backstairs). Der Gang in die Nacht, which came out before either of these, isn’t usually considered an example. It’s interesting that the review I quoted, based on a December 1920 press screening, sees Murnau’s film as anticipating the trend. Perhaps the more rigorous concentration of time and space in the later films made critics take them for purer prototypes of the genre.

Knowing this background, I think, makes Der Gang in die Nacht more intriguing than it might at first seem. But another context is important too. The film shows Murnau’s debt to an important stylistic tradition. What he did with it is in sync with other filmmakers learning their craft at the same time. (Some spoilers ahead.)

Tableau + insert = proto-continuity

During the years 1908-1920, many filmmakers relied a “tableau” style of filmmaking. The used long shots and long takes, with the actors shifting in expressive patterns around the setting. The tableau might be broken up with titles or close-ups of letters or diaries, but the drama is developed through action played out in the distant framing.

Early historians, and many still today, portray this approach as merely “theatrical.” In fact, because of the way the camera lens creates a pyramidal playing space (the tip resting on the lens), the tableau approach is very different from proscenium theatre, which has a wide, lateral playing space. The result is a choreography of figure movement in breadth and depth that is no less “cinematic”—that is, specific to the film medium—than editing.

Want clarification? There’s a video lecture here, and more discussion in these entries.

In the course of the 1910s, however, filmmakers started to alter this approach. For one thing, they started to cut up the tableau more. American filmmakers were most radical, often abandoning the long shot altogether and building scenes out of several partial views—medium-shots and close-ups. But most European filmmakers were more conservative. They began to use what researchers have come to call the scene-insert method.

The tableau (the “scene”) would be interrupted by one or two closer views of a face or gesture, before returning to the main framing. Almost always the inserted shot is taken from the same camera position as the long shot. The cut is “axial,” along the lens axis of the camera. It enlarges a slice of space given in the wider view, then usually cuts back along the axis to reestablish the tableau.

Here’s a simple example from Joe May’s delightful serial Die Herrin der Welt (Mistress of the World, 1919-1920), when a nurse in the room in the background rises.

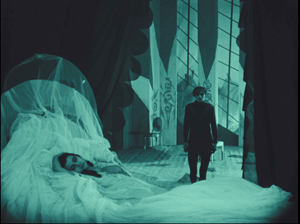

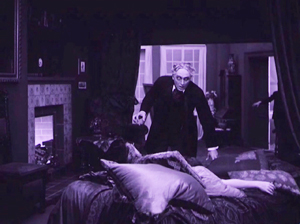

The axial approach is used throughout Caligari too. When Cesare invades Jane’s bedroom, we cut straight in and then cut back as he approaches.

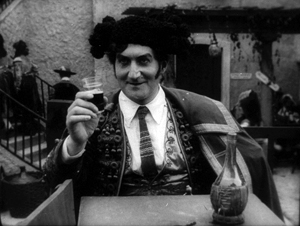

In Kristin’s book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available as a pdf) she traces several instances in other German films, as in this passage from Carmen (1919), with Don José way back at the rear of the tavern–but still on the lens axis.

Der Gang follows the scene-insert method often. The only closer view during Lily’s tea flirtation with Börne emphasizes her teasing gesture and his reaction.

The result is a minimal version of analytical editing, a sort of rough, proto-continuity approach to breaking up a scene into details. It can be thought of as a transitional phase toward a fully “classical” style of staging and cutting, and indeed in the 1920s more and more European filmmakers adopt versions of the Hollywood method.

Already, we can see some filmmakers thinking in terms of an establishing shot rather than a tableau. Murnau’s long shot below is probably too far distant to permit a complex play of depth of the sort we see in Caligari and Carmen. It’s designed, we might say, to be cut into.

During this transitional period, we find films exploring the scene-insert method in intriguing ways. The most evident is the tendency to make the cut-in shot very close.

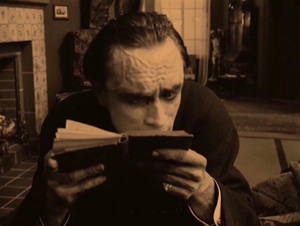

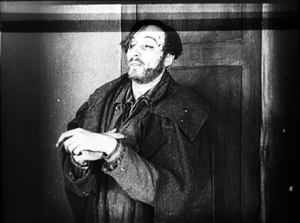

In Paul Leni’s Dr. Hart’s Diary (Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart, 1918), for instance, we get a rather distant shot showing the wounded Count Bronislaw carried out of the ambulance, followed by a very tight medium-close-up of him and Jadwiga, the Red Cross nurse.

An American director would have been more likely to soften this sudden enlargement with a mid-range two-shot of the couple before providing the intense close-up of their faces.

This abrupt jump into a surprisingly close view isn’t uncommon in European cinema of the period, and it’s particularly salient in German films. The insert is often taken with a wide-angle lens, which can accentuate the curves and edges of a face. Murnau’s fondness for the wide-angle lens is a constant throughout his career. A fragment from his first, lost film The Blue Boy shows a wide-angle depth composition, and there’s an astonishing wide-angle close-up of the distraught painter in Der Gang.

Like many directors working in this line, Murnau balances the power of the sustained long shot with the momentary spike of the closer view. A good example comes in the beautiful passage when Börne discovers that Lily is dead. The setup is given in a classic tableau framing, with only her arm extending out from cushions on the divan. Then the Painter’s head lifts into center frame from behind the pillows, a slow revelation of his pain.

After alternating cuts to Börne hammering at the door, the Painter rises and floats to the door in the back wall. (The rear door is a fixture of the tableau tradition, as it allows for dynamic movement in depth within the visual pyramid.) Once the doctor is admitted, he rushes forward and pauses as the Painter glides into the background.

As Börne wails, Murnau pushes us into the parlor to the Painter, standing in the distant corner like an upright corpse—an alternative version of grief.

Like many films of the period, not only German but also French and Italian ones, Der Gang in die Nacht exploits the resources of the tableau—the graceful, expressive coordination of actors who perform with their whole bodies—while saving the blunt force of the isolated face for a climactic accent. No wonder that film theorists of the late ‘teens and early 1920s were fascinated by close-ups; they were seeing a great many vivid ones.

Not haunted, just mysterious

There were a lot of variants on these techniques. As if to give us the tableau and the wide-angle insert in a single frame, Robert Reinert cultivated a looming deep-focus style that suggests a Citizen Kane of the 1910s. The first frame is from Opium, the last two from Nerven (both 1919).

And the extraordinary Weisse Pfau (The White Peacock, 1920) of E. A, Dupont comfortably switches from a dizzying gridded tableau (two men arriving at a theatre lobby, caught in an architectural Advent calendar) to a violent climax using highly fragmented editing.

By 1921 the simplest version of the tableau-plus-insert method was rapidly going out of favor. To get a sense of how techniques were changing at the time, you should watch Murnau’s Schloss Vogelöd (1921) immediately after seeing Der Gang in die Nacht.

The plot is a bit friendlier to our pulpy tastes, involving a past murder that is brought to light during a country house party. (No spooks haunt the castle, just the lingering effects of mysterious death.) Again, there’s a chamber-play aspect to it. Virtually all the action is confined to the mansion of the host, von Vogelschrey, and plays out in a couple of days and nights.

Schloss Vogelöd was released only three months after Der Gang in die Nacht. In the sparkling restoration provided by the Murnau Stiftung, Schloss runs almost exactly as long as the earlier film. But what a difference! I count 231 shots in Der Gang, with 163 of those being images, not titles. I count 511 shots in Schloss, with 356 of those being images. Assuming a common projection speed, the later film is cut over twice as fast.

The sheer number of shots is important, but the crucial factor is that many of the shots in Der Gang retain one particular framing, interrupted by titles or a diary or letter insert. Not only does Schloss have more shots, it has more varied setups. Murnau is shifting his camera positions more often, as were his peers Lang and Dupont, along with other Europeans and of course the Americans.

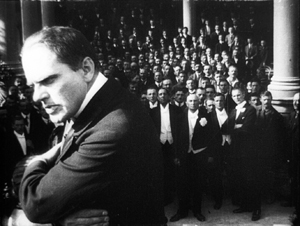

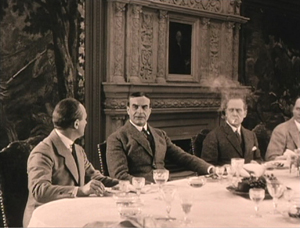

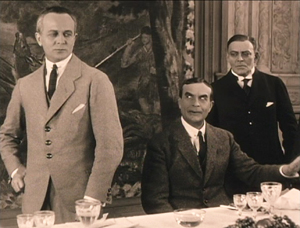

Here’s an example. At a meal, the vengeful Count Oetsch hints that Baron Safferstädt is the murderer. The scene runs about three minutes and contains 16 shots and five titles, played out across six distinct setups. I sample them here.

In a loose sense, the cuts are axial, enlarging or de-enlarging parts of the table as observed from one general orientation. (The judge who stands up and looks left is at the foot of the table.) But within this overall orientation, there’s a variety of setups we don’t find in Der Gang. We aren’t far from that spatial ubiquity and adherence to an axis of action that was pioneered in 1910s Hollywood and would become increasingly common in Europe during the 1920s. The downside: The development of more finely broken-down scenes led to a loss of the complex choreography within a single shot that was common in the early 1910s.

Der Gang in die Nacht was filmed in August-September of 1920; Schloss Vogelöd was shot in February and March of 1921. In between Murnau made Marizza, genannt die Schmuggler Madonna (Marizza, called the Smuggler’s Madonna, not shown until 1922). The fragments of this that have survived are very rudimentary filmmaking, much simpler than anything in either of the other two films.

The faster cutting and more varied setups of Schloss may, as Kristin has suggested, owe something to the arrival of American films. Banned until January 1921, they may have inspired German directors to push further toward analytical editing. She has also mentioned in Exporting Entertainment that some American films did slip through the ban and get screened during the war years, so directors could have had an inkling of what Hollywood was up to.

In any event, Der Gang in die Nacht admirably lays out one set of directorial options that emerged as filmmakers of the first “movie generation” (Murnau, Dreyer, Gance, Lang, Dupont et al.) shifted away from the pure tableau style. All became virtuosos of editing, but they never forgot the power of the sustained long take.

Thanks to Stefan Drössler of the Munich Filmmuseum for information on the restored Der Gang in die Nacht. Thanks as well to Sabine Gross for her translation of German material. As ever, I owe an enormous debt to Gabrielle Claes and Nicola Mazzanti of the Cinematek in Brussels.

The review citing Der Gang as a Kammerspielfilm is reprinted in Film-Kurier (30 December 1920), 2. I was led to this by Lotte Eisner’s Murnau (University of California Press, 1964), 92. Although it’s long been out of print, her book remains a very useful source. Also helpful are Los Proverbios chinos de F. W. Murnau, vol. 1, ed. Luciano Berriatúa (Filmoteca Española, 1990) and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: Ein Melancholiker des Films, ed. Hans Helmut Prinzler (Deutsche Kinemathek, 2003).

Schloss Vogelöd is available on two DVD editions, one from Kino and the other from Masters of Cinema. My frames come from the Kino edition, chiefly because they’re brighter than the higher-contrast MoC edition, and thus more legible on the Net. Both editions have their strong points, as DVDBeaver indicates. Surviving frames of Murnau’s first film are available on the Lost Films website.

Many issues of tableau style and its relation to editing technique are discussed in my On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging, and Poetics of Cinema. On this site, among entries on the tableau tradition, the entry most relevant to today’s piece is “Not quite lost shadows.” I discuss Danish approaches to the tableau in the essay “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” and the case of Dreyer’s relation to his peers in “The Dreyer Generation,” on the Danish Film Institute website.

Karl Friedrich Schinkel, The Banks of the Spree Near Stralau (1817).

Back on the trail of THE CHASE

DB here:

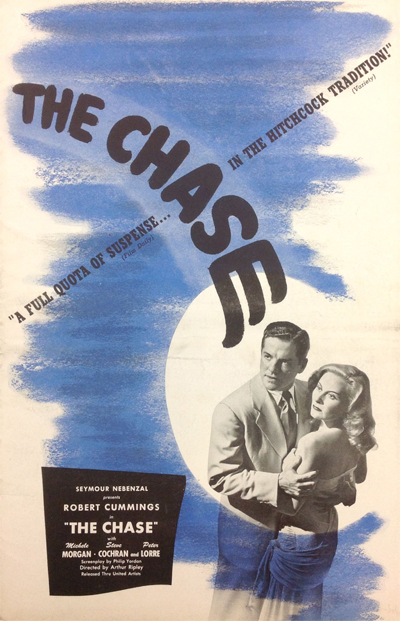

How did The Chase (1946) come to be such a weird movie?

Exploring that question in an August entry, I complained: “I haven’t located any scripts, alas.” I was forced to use what evidence I could muster from trade papers and the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Now I’ve learned of one screenplay for the film, and it confirms my primary conjectures—while offering some other complications. (What else is new?) You may want to return to that earlier entry before moving on with this, but this can stand on its own. Of course there are many spoilers ahead.

The screenplay is signed by Philip Yordan and dated 17 April 1946, with some inserted pages dated 16 May. It is held in the collection of the producer, Seymour Nebenzal, housed at the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Droessler and Christoph Michel supplied information about this document, and Miriam Landwehr produced a detailed synopsis and a comparison to the finished film. I’m very grateful to them for their assistance.

When is a dream not a dream?

The problem of the film as we have it is its And-then-I-woke-up plot. Navy veteran Chuck Scott takes a job as a chauffeur to Eddie Roman, who runs a smuggling racket with his henchman Gino. Roman’s wife Lorna longs to escape the marriage and induces Chuck to buy her passage on a ship bound for Cuba. Chuck, infatuated, flees with her, but in Havana she is killed in a nightclub and Chuck is the prime suspect.

Escaping from the cops, Chuck is killed by Gino, who has trailed the couple to Cuba. And now Chuck wakes up. We realize that the escape to Havana has been a dream that he’s had on the night he and Lorna were to sail. This rupture in the story action has been a crux for the film’s many admirers—a sheer piece of noir bravado.

Unfortunately, the dream has triggered Chuck’s old war trauma and he has amnesia. He can’t recall anything of the Miami episode. He returns to his doctor, who helps him recover his memory, rescue Lorna, and actually set out for Cuba with her. The film ends with the two in a carriage outside the nightclub that they visited in Chuck’s dream. This too has aroused a lot of comment; how could they visit in reality what Chuck only imagined?

These and other anomalies in the film, along with a 1946 remark by Nebenzal about eliminating the screenplay’s “flashback,” led me to look into the production. Crucial as well were Cornell Woolrich’s original novel, The Black Path of Fear, and an anonymous novelization of the film published in Movie Mystery Magazine (December—January 1946). Since novelizations were often written on the basis of scripts, I inferred that aspects of the screenplay might have been preserved in that publication.

These and other anomalies in the film, along with a 1946 remark by Nebenzal about eliminating the screenplay’s “flashback,” led me to look into the production. Crucial as well were Cornell Woolrich’s original novel, The Black Path of Fear, and an anonymous novelization of the film published in Movie Mystery Magazine (December—January 1946). Since novelizations were often written on the basis of scripts, I inferred that aspects of the screenplay might have been preserved in that publication.

The original novel begins in Havana, where Lorna dies in the nightclub. Fleeing the police, Chuck tells Midnight, a woman who hides him, of how he met Lorna and Eddie Roman in Miami. At the end of this flashback, he sets out across Havana to find Lorna’s killer.

The central production decision, evidently taken by Nebenzal early on, was that in the film Lorna was to live and unite romantically with Chuck. How to keep Lorna alive and yet retain the dramatic murder and Chuck’s flight from the law?

Yordan’s screenplay, fairly closely followed by the novelization, adhered to Woolrich’s opening by starting with the Havana murder and letting Chuck recount the Miami backstory to Midnight. But then, on the trail of Lorna’s killer, the screenplay has Chuck killed by Gino. Then Chuck wakes up. We realize that the entire first part of the film—running an hour or so—has been his dream. So Lorna is kept alive for a genuine partnering and flight with Chuck.

The screenplay’s problem is that Chuck has dreamed not only the imaginary murder but everything leading up to it. What he tells Midnight in his dream includes all the veridical backstory of his becoming Roman’s chauffeur, learning of Lorna’s desire to escape, and fleeing with her. The dream, false in its Cuban sections, is faithful to actuality in most of its Miami stretch—the flashback that novel included and that Yordan retained.

That Miami backstory was the flashback that Nebenzal eliminated late in production, claiming that he felt there were too many flashback movies in release. He shifted the Miami scenes to the front of the movie, where they serve as conventional chronological action, and made the Midnight encounter in Chuck’s dream a straightforward scene in which she helps him evade the police.

Not quite rounded with a sleep

The screenplay and the novelization fool us by eliminating the dream’s “front frame.” There’s no scene showing Chuck going to sleep; we’re immediately in his imaginary Havana. By contrast, contemporaneous films using the dream device supplied at least a minimal setup. The Woman in the Window (1944), The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945), and Strange Impersonation (released April 1946) each include an innocuous piece of action that, in retrospect, indicates that the protagonist has fallen asleep and dreamed what we’ve just seen. The return to those setup situations tips us off that we’ve just seen a dream.

Evidently Yordan wanted to take this trend further by lopping off the setup altogether and plunging us straight into a dreamscape for a very long stretch. By killing the protagonist, Yordan supplied a shock that, given Hollywood conventions, would have to be recouped somehow. The dream device does that, bringing both hero and heroine back to life.

Once the flashback was shifted to the front of the film, however, Nebenzal needed a more conventional front frame to bracket off the dreamed escape to Cuba. Therefore he supplied a scene showing Chuck lying down just before he and Lorna are to flee. This scene is not in the screenplay or the novelization.

As in other films of the time, the setup is equivocal. Chuck lies down and reads a newspaper and just barely starts to yawn as the film fades out. Cunningly, as I pointed out in the earlier entry, there’s a bridge of diegetic music—the piano concerto that Roman is listening to on the phonograph—and we then see Roman and Gino in the living room. A more typical dream film would remain attached to the dreamer; we might see Chuck get up from the bed, close his suitcase, and sneak out with Lorna. Instead, we’re with Gino when he goes to Chuck’s room, finds him gone, and reports his departure to a curiously listless Roman. So Chuck dreams Gino’s discovery of his departure. The shift to Roman and Gino seems to corroborate the objectivity of what’s happening, especially because the film’s non-dream stretches have freely intercut Chuck’s actions with those of his boss.

In the earlier entry I pointed out some visual anomalies among the framing scene, the scene of Gino visiting Chuck’s room, and the waking-up scene. Changes in props suggest that the retakes to which Nebenzal alluded in a memo in August may have included shooting the setup frame. By mid-September he was announcing that he had abandoned the flashback, and the film was completed by 7 October.

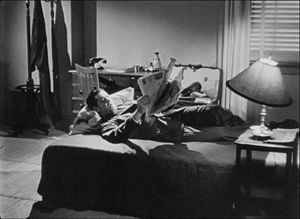

For those of a fussbudget inclination, like me, you can find hints that the original waking-up scene was modified to fit the front frame that was added later. Here’s the waking-up framing shot, which tracks back from the ringing telephone.

The lighting, setting, and camera angle closely match what we realize in retrospect was the setup of Chuck falling asleep.

But the closer views of Chuck woozily coming out of his dream vary from neighboring shots in tonality and in the position of the chair behind him. (In the master shot it’s angled to our right, but in this and other shots it’s angled to the left.)

Later shots in the waking-up scene show different positions of other props. While the chair remains angled to the left, the lampshade (tipped in the earlier establishing shots) is upright now; there’s no longer a magazine behind the lamp; and the water carafe and pills on the desk are in a slightly different array.

In addition, the lighting scheme is somewhat different; the interior of Chuck’s suitcase is blown to pale gray in the framing shots but in the ones above it’s far darker. And the coat and coatrack visible on frame left of the dream frame aren’t visible in the widest shot we get later in the scene, the second one above.

I know: Picky, picky. We could put these disparities down to routine continuity errors. But their patterned differences are consistent with their being part of a patchwork. It seems plausible that most of the waking-up scene was shot during principal photography, but the opening shot of that scene, along with the falling-asleep frame that was added, was filmed during the retakes that Nebenzal oversaw in August and September.

Cabin fever

One of the weirdest aspects of the film we have is the ending. Eddie Roman and Gino, racing to stop Chuck and Lorna from escaping, smash into a locomotive. This chase is intercut with Chuck and Lorna in a ship’s cabin waiting to sail off. The problem is that, for censorship reasons, this unmarried couple can’t easily be shown running off together, and sharing the same quarters at that.

Several commentators have noted that the set recalls the one that Chuck dreams (below, left).

The cabins aren’t all that much alike, though the clock on the back wall probably pops out as a reminder. Yordan’s script asks that the second cabin suggest the first one.

This set should be basically the same as the set used before yet there must be distinct differences.

It seems that Yordan wanted to hint that Chuck’s dream was a sort of premonition of the trip they’d wind up taking. The dialogue flirts with the possibility. As Lorna says, “For once in my life I wish I could want something that was good for me,” the screenplay goes on:

At this point, something happens to Chuck. He becomes aware that he has heard this line before. Suddenly he knows everything that she is going to say, everything that’s in her heart.

When he suggests she tries to recover her lost innocence, she asks: “You haven’t been drinking, have you?” he replies: “No–just dreaming.”

He adds that he’s dreaming “what a chauffeur’s not supposed to dream about.” Wanting to give her freedom, he decides not to go to Cuba with her and vows to reenlist in the service. They don’t embrace. Quick dissolve to Chuck marching in a military parade down Fifth Avenue. His decision not to have a runaway romance is rewarded by the sight of Lorna, now his wife, cheering him from the sidewalk. It’s on this burst of patriotism that the screenplay ends.

Was this preposterous epilogue ever shot? Had it been jettisoned by the start of production on 16 May, presumably the 14 April script wouldn’t have included it (since it includes some revisions dated 16 May). But the parade isn’t in the novelization, which is otherwise very faithful to the April script. The novelization was based on a script sent to the magazine in late June or early July, so perhaps the parade was dropped after principal photography began. We do know that in September Nebenzal was shooting alternative endings.

The novelization’s cabin scene follows the screenplay’s tack, indicating that Chuck’s “dream” of union with Lorna should end with the couple splitting up. But she resists his suggestion, and things take a familiar turn.

And in the next instant, Chuck’s mouth found her warm lips, shutting off her words, his arms pressing her to him crushingly.

This burst of passion is interrupted by a telegram from Dr. Davidson telling Chuck of Eddie’s death. The message asks the couple to return, in a wry phrasing: “Before you get into any real trouble in Havana.” This version concludes with them agreeing to get off the ship and get married, so they never sail for Havana. No parade finale here.

The film’s last moments, as any aficionado knows, are something else again. The scene in the cabin is played eerily, with Chuck striding in and glancing at a newspaper he’s carrying. When she asks when the boat will get started, he says, “It doesn’t matter now.” Did the newspaper carry news of Roman’s crash? (Unlikely, so soon.) And why doesn’t he take Lorna in his arms, for the clinch and fade-out? Did the production team not have the footage, after shooting the lead-in to the parade?

The film’s epilogue, absent from both the script and the novelization, casts aside any concern about whether this furtive couple has married or not. We’re back in front of the La Habana club, with Chuck and Lorna in the carriage declaring their love for one another.

This scene (below left), as I suggested in the August entry, is quarried out of footage shot for Chuck’s dream (below right), right down to the grumpy driver.

The result is pretty Buñuelian. You can call it a reenactment of the dream in real life. Or you can say that it plunges us back into Chuck’s dream–leaving the shipboard resolution suspended. In their haste to wrap things up, Nebenzal and his director Arthur Ripley give us the conventional clinch, all right, but with a screwball spin.

So my conjecture about the original ordering of the film’s plot is borne out by the discovery of the screenplay. But we still don’t know why the film, once the parade epilogue was jettisoned, doesn’t include the clinch in the cabin and the resolution to marry. Both were in the novelization. Why go back to the Habana club and the recycled footage? Only further research into other production documents can tell us for sure. In the meantime, we’re left with another Forties film that flaunts the unexpected virtues of accidental innovation.

The Chase was restored by UCLA and is available on a handsome Blu-ray edition from Kino Lorber. My references to production materials and press releases for the film come from the sources listed in the earlier entry. One of my illustrations above comes from a French novelization that I haven’t yet found; I assume that it’s a translation of the English one, but maybe not.

This isn’t the first time I’ve returned to fuss over an earlier entry. I did it with The Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here and here) and twice with Hitchcock’s ideas of suspense (here and here). If I keep trying, maybe I’ll get it right.

Surprisingly, the dream device was built into the studio’s publicity to a small extent. (See images below.)

P.S. 2 November 2016: David Koepp, film noir aficionado, adroit screenwriter and director, and one of the People We Like, writes:

I love your blog post on The Chase. Just read it, and, coincidentally, I just watched The Chase yesterday and had been meaning to e-mail you about it. You’ve said pretty much all there is to say about that movie already (and with your customary thoughtfulness), but just two things I wanted to add.

First, this film stretches the kind phrase “bold use of coincidence” to new extremes. There is seemingly NO situation that they weren’t comfortable having resolved, furthered, or complicated by coincidence, and in a strange way I kind of came to appreciate that. I mean, it’s economical, if nothing else.

But my second thing is more interesting. It’s funny that you focus today on the falling-asleep framing device for the dream sequence, because I had an observation in that very spot, a curious bit of staging which I didn’t fully understand, but now I think I do thanks to your post. After the master shot pulls back from the phone, Robert Cummings goes to the bed and does the strangest thing. He picks up the pillow, tosses it to the foot of the bed, and lays down on the bed for his fateful nap, WITH HIS SHOES ON. Think about that — he picks up the pillow from the socially agreed-upon head of the bed, tosses it to the foot of the bed, and then lies down with his dirty shoes on the now-unprotected sheet at the head of the bed. Who in God’s name would do that?

Only one person I can think of — an actor who’s been asked by the director to do it to protect the composition. In its widest position, the lamp in the right foreground blocks the head of the bed and the remainder of the set to the right, and the master shot plays beautifully as one long pullback. So, at first I figured the director just liked his master and asked the actor to toss the pillow to the foot of the bed, i.e., “I know it’s weird, Bob, but would you mind?, it’s a lovely shot and I don’t want to have to break it up and turn around to shoot you at the head of the bed.”

But there’s another possible reason, if your reshoot theory is correct. Which is that they were rushing to squeeze in a clarifying reshoot, struggling to recreate the set and props as they were in the original footage, and they didn’t want/didn’t have time to/couldn’t afford to rebuild the other walls of the set to accommodate. Plus there’s a door in the wall to camera right, and a hallway outside it with a return. More stuff to build–way too expensive and time-consuming for the hurry-up-and-grab-this approach they’d need for a reshoot with the studio and the release date breathing down their necks.

Maybe? Who knows! But it’s fun to speculate.

It’s interesting that in the April screenplay, Yordan doesn’t specify that Chuck is sleeping at the foot of his bed. We simply have: “Chuck lying on his cot, fully dressed in his chauffeur’s uniform.” David’s point is persuasive to me. It would be harder to compose a pull-back from the phone (a gradual revelation that Yordan’s screenplay insists on) if Chuck were lying at the head of the bed. The awakened shots not made during the reshoots also have Chuck sleeping at the foot of the bed, but David’s point about the composition makes sense for those too.

David’s mention of Chuck’s position makes me think about something else. Lying at the foot of the bed also suggests, to me at least, an intention of not going to sleep but rather just relaxing. Had Chuck stretched out on the bed normally, might we be more inclined to suspect a dream was coming on?

Thanks to David for sharing the practical filmmaker’s perspective! Now more than ever I’d like to see the daily set reports for this movie.

P.P.P. 13 November 2016: For hardcore fans only: At the suggestion of Soren Schoff, a local friend, I obtained a copy of the UK novelization of The Chase, published by Hollywood Publications of London in 1947. It’s signed by Kit Porlock, a name one sees on many novelizations published in London in the Forties. This text is quite different from the Movie Mystery Magazine edition, and it adheres closely to the finished film. But there are interesting aspects to it.

Like the movie, it starts with Chuck in Miami and follows him through the romance with Lorna. The front end of the dream frame, just before he’s about to run off with Lorna, is given more explicitly than in the film:

Like the movie, it starts with Chuck in Miami and follows him through the romance with Lorna. The front end of the dream frame, just before he’s about to run off with Lorna, is given more explicitly than in the film:

He stretched out on the divan for a while. He had nothing to do for the next four or five hours. A nap would be sensible if only he could get to sleep.

He took a couple of his pills and tried to relax. It was no good. Too many images and fancies revolved in his brain. He readjusted the pillow under his head and sprawled out luxuriously Just to have an hour or so would do him the world of good. . . . .

This ends a chapter. The next chapter begins with Gino entering and finding Chuck gone, more or less as in the film.

When Chuck comes out of the Havana dream, the novelization likewise makes sure we know it wasn’t real (“All that was so vivid to him had only been a dream!”). But the amnesia has kicked in and so Chuck has to seek help from Dr. Davidson, as in the film.

There are two only other major differences from the finished film. For one thing, like the US adaptation, the UK one ends with Lorna and Chuck in the ship’s cabin. Here it’s clear that the ship has delayed departure long enough for a newspaper edition to arrive and announce the deaths of Roman and Gino in the car crash. In the film, Chuck simply comes in with a folded newspaper, and we aren’t explicitly told why he now thinks the two of them are safe. Maybe the final release just dropped his act of showing her the news item.

The second difference from the film is that, like the MMM version, the story ends in the cabin with the couple united in love. There’s no epilogue in the carriage outside the La Habana club. This novelization, said to be “from the original film script,” isn’t, but perhaps it’s based on a rewrite that was closer to the final release–that is, after Nebenzal had shifted the flashback to the front of the plot and had jettisoned the military-parade finale. But we still have to wonder why the final cabin clinch in both novelizations isn’t there in the film, and why the carriage scene isn’t in either novelization. The Chase remains elusive.

The Chase (1946) United Artists pressbook.