Going inside by staying outside: L’AVVENTURA on the Criterion Channel

Thursday | March 23, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

This month, our entry on FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel is a discussion of L’Avventura. This isn’t my favorite Antonioni movie, but it’s one I enjoy and admire—not least because of its striking originality of mise-en-scene. So that’s what I tackle in the Criterion entry.

The installment is here, and if you’re a subscriber you can watch it immediately. Otherwise, there’s a chance to sign up. If you’re not aware of FilmStruck, one of the great adventures in modern film culture, you can check on it here. (The Twitter feed is enjoyable even to non-tweeters like me.) Today, I want to flesh out my entry with some other comments. I hope they’ll be of interest even to those who aren’t signed on to the FilmStruck enterprise.

Two ways of doing deep

Le Amiche (1955).

During the 1950s, Antonioni displayed vigorous experimentation in visual style. Like many directors, he embraced the long take, usually in conjunction with camera movement. Within those parameters, he staged his action both laterally and in depth. But depth staging comes in many flavors.

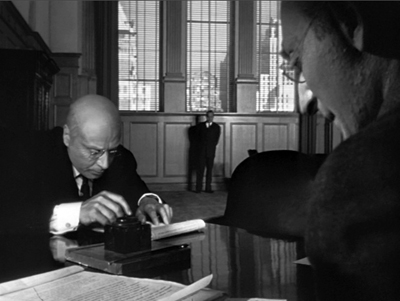

One is the aggressive deep-focus technique of Welles, with large heads or objects very close to the camera in the foreground. Here are two famous instances from Citizen Kane (1941).

This fairly extreme approach was picked up by some 40s and 50s directors, especially those interested in what came to be called film noir.

You can find somewhat mild versions of these compositions in early Antonioni, especially in cramped surroundings. A bus ride and a necking party in I Vinti (1953) bring forth some big foregrounds.

Despite occasional shots like these, Antonioni’s early work favors an alternative approach to depth, the one cultivated by Jean Renoir, Mizoguchi Kenji, William Wyler, and others. That approach doesn’t go for Citizen Kane baroque. It keeps the foreground plane fairly distant–say a medium-shot or further–and uses both lateral and fairly deep staging to multiply key points of interest in the shot. Less fancy than the Welles tradition, it allows more naturalistic blocking because it yields more playing space.

Go back to I Vinti, and we’ll find that most shots aren’t as thrusting as Welles’ images, largely because of their reliance on real locations and naturalistic lighting. The film tends to stages its long takes in mid-range, porous compositions. A two-minute shot of teenagers lounging at a cafe and plotting a murder is rendered in a gentle diagonal that spreads out multiple points of interest.

By the way: Why doesn’t anybody make shots like this any more?

One advantage is that while the packed Wellesian frame tends to make its actors assume fixed poses, the more open frames of the alternative can show more of actors’ bodies and develop gestures and other actorly bits. This happens in the I Vinti café scene, which depends on characters’ changing postures, along with the distraction of the annoying little girl blowing on drink straws.

Similarly, Antonioni’s first feature, the noirish romance Story of a Love Affair (1950) makes adroit use of the mid-range foreground. The famous single-shot, 360-rdegree scene between lovers quarreling on a bridge is a paradigm case of how location filming can be made rigorous and purposeful. A complex camera camera movement is coordinated with figures resolutely evading each other in constantly varied medium-shots.

Le Amiche (1955) continues down the same path, with characters alotted distinct pockets of the frame to expose their fleeting reactions.

But there’s now a more intricate choreography, as befits a plot with several story lines. A scene gathering the major characters at a cafe is a magnificent exercise in the Wyler manner, with heads meticulously spotted across the frame.

For years I was surprised that L’Avventura (1960) and its successors La Notte (1961) and L’Eclisse (1962) make less use of this sort of precise staging in depth. While the director’s style remains fluid and rigorously patterned, and powerfully exploits urban vistas, it relies more on editing. But looking again at L’Avventura for the Criterion Channel installment, I became convinced that he was exploring a new way to handle staging—one that built upon his mastery of Renoir-Wyler choreography.

From the back or from the front

When a film’s narrative harbors mysteries, they’re often a matter of plot. Something has happened that we don’t fully know about, and the business of the plot is to bring that to light, either in the short term or across the whole movie. In the detective film, there’s a mysterious crime that needs solving, and the clarification will typically come at the climax, when the malefactor (and the motive, and the means) will get revealed. Plot-centered mysteries are easily dismissed as superficial, but the great tradition of literary detection shows that they can be imaginative and gripping, while also exploring literary techniques in sophisticated ways.

There are also mysteries of character—not just whodunit, but something deeper. A narrative might induce us to ask what makes characters do what they do. This can result in fairly superficial probing, as in many psychoanalytic films of the 1940s, but it can, again, prod the storyteller to exploit some aspects of the medium that engage us. At the limit, mysteries of character can lead the narrative to explore the moods and motives of its people, bringing out contradictions of mind and action. Even a potboiler like Gone Girl not only reveals the rage bubbling beneath Amy’s perfect porcelain surface but explains that anger as a response to the Cool Girl role dictated by yuppie culture.

I usually don’t employ the distinction plot vs. character when I’m thinking about film narratives, but as a first approximation it points up the nuances of L’Avventura’s visual strategies. The film has, initially, a clear-cut plot-based mystery: What has led Anna to disappear? Is she dead, or lost, or simply escaping from the situation? This is, in a way, the bait luring us to pursue mysteries of character.

What, to start, does Anna want from her affair with Sandro? She seems alternately flirtatious, cynical, angry, and passionate. And assuming her disappearance wasn’t accidental, what impelled her to leave the party? As for Sandro, what sort of man is he? And why does he, with unseemly haste after Anna’s vanishing, seize Claudia and kiss her violently?

Claudia, for her part, seems to gradually accept her role as the Anna substitute. We’d expect her to be torn by her betrayal of her friend, and maybe she is, but we can’t be sure. With almost no backstory supplied for these people and no plunge into their inner lives through dreams, voice-over, subjective visions, and the like, we’re forced to read their minds and hearts on the basis of what they say and do. This is relentlessly behaviorist cinema.

Here’s where visual style kicks in, I think. Antonioni declared his interest in moving the Neorealist impulse from social observation to psychological revelation.

The neorealism of the postwar period, when reality was what it was, so intensely present, focused on the relationship between characters and reality. What was important was that very relationship, which created a cinema based on “situations.” . . . That’s why, nowadays it’s no longer important to make a film about a man whose bicycle has been stolen. . . . It is important to see what is inside this man whose bicycle was stolen, what are his thoughts, what are his feelings.

How to achieve this psychological penetration? Not through the sort of definite scene structure of a Hollywood film, a crisp slice of action that can be summed up in a story beat.

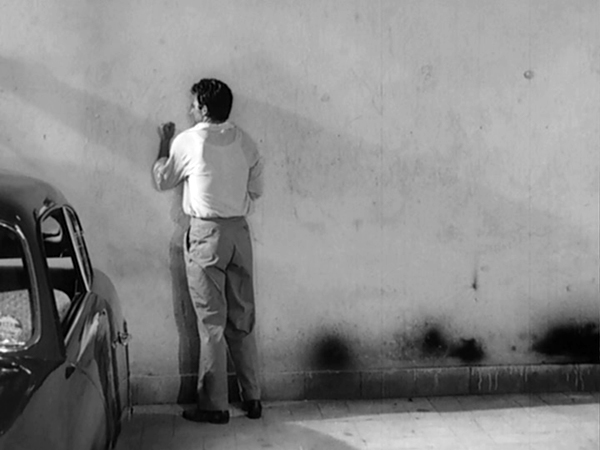

I believe it is much more cinematic to try and capture the thoughts of a person through an ordinary visual reaction, rather than enclose them in a sentence. . . . One of my concerns in filming is to follow the characters until I feel it is time to stop. . . When all has been said, when the main scene is over, there are less important moments; and to me, it seems worthwhile to show the character right in these moments, from the back or the front, focusing on a gesture, on an attitude.

Antonioni scenes, critics sometimes say, begin a bit before they start and end a bit after they stop.

You might expect from this emphasis on character psychology and the habit of lingering on a scene’s resonance would yield few mysteries. Yet what interests me in L’Avventura is the way in which it doesn’t allow us to “see what is inside” its characters. Perversely, having braked the dramatic momentum in order to probe character, Antonioni goes on to block our access to his people’s minds.

His visual strategies for doing this are many, and they’re flaunted in the film made just before L’Avventura. The witholding of character reaction is flamboyant in Il Grido (1957), maybe over the top.

L’Avventura‘s reticent pictorial strategies are more nuanced and naturalistic, and my FilmStruck contribution tries to chart them. For about the first hour of the film, Antonioni lets landscape overwhelms his characters, gives them equivocal facial expressions, refuses the full information of shot/reverse shot cutting, and at crucial moments simply makes his actors turn from the camera, denying us access to their emotional reactions.

What’s just as interesting, the second half of the film selectively returns to the techniques that were initially banned. It’s as if these more familiar image schemas–reverse shots, frontal close-ups, more marked facial reactions–have become suitable to the growing romance between Claudia and Sandro. Now the first hour’s stingy attitude toward psychological information is balanced by a greater degree of emotional exposure, especially on Claudia’s part. By the very end, the two broad strategies coexist uneasily, and some enigmas remain.

During the late 1960s Antonioni changed his style. He turned from deep-focus, wide-angle images to flat telephoto ones, and he began relying on a pan-and-zoom technique. These were partly responses to shooting in color and wider formats, I think, but they also offered the opportunity for a painterly look that he exploited in the films from Red Desert (1964) on. Fellini, Bergman, Visconti, and others took a similar path, as I tried to show in this early blog post.

In 1960 those developments were yet to come. It seems to me that the style of L’Avventura enhances the mysteries of plot and character in a unique and unsettling way. We get a visual surface that entrances us with its measured beauty and teases us with its calm opacity.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the Criterion team for including us in their FilmStruck enterprise.

My quotation from Antonioni comes from his essay “My Experience [1958],” in his book The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema (Marsilio, 1996), 7-9.

The L’Avventura discussion on FilmStruck is the fourth in our Criterion Channel series, “Observations on Film Art.” The others are Jeff Smith on the music of Foreign Correspondent, me on Sanshiro Sugata, and Kristin on landscape in Kiarostami. Some clip extracts can be found here and here. Jeff has amplified his installment with further comments on this blog, and I’ve done the same with Sanshiro , as today with L’Avventura. We introduce our collaboration in this entry. The Criterion introduction to us is here.

For more on Mizoguchi’s approach to depth staging, see this summary entry. There’s more on Wyler’s style here. I compare the two directors in this entry on sleeves. I discuss the broader shift from deep-focus techniques to pan-and-zoom ones in On the History of Film Style, Chapter 6.

I Vinti.