Archive for April 2017

Film noir, a hundred years ago

A Romance of the Air (1918).

DB here:

One of the most persistent conventions in American cinema associates dark images with dangerous doings—crime, mystery, violence, espionage, sexual depredations, visits from beyond the grave. The strategy is most apparent in what critics eventually called film noir. Those 1940s “films of darkness” are sometimes said to derive from German Expressionist cinema, but the look was already a Hollywood tradition. Filmmakers had long treated scenes of mystery and suspense with hard, low-key lighting that yielded rich chiaroscuro.

When does it start? You can find very early examples, but it seems to have crystallized during the 1910s. Kristin has talked about this as a period when filmmakers were collectively struggling to tell somewhat lengthy stories in a clear fashion. Along with clarity, she argues, came efforts to add emotional impact to a scene. Those included dynamic staging, fast cutting, close-up framings, subtle but arresting performance styles, ambitious camera movements, and lighting that enhanced the mood of the action. She points to many European and American films of the years 1912-1916 that flaunt silhouettes and selective lighting.

I found a lot of prototypes of noirish images during my recent trawling through Library of Congress films from 1914-1918. In this era, it seems, filmmakers competed to create striking, even shocking, lighting effects. Later directors and cinematographers would adopt many of them as proven tools for boosting their scenes’ emotional power.

So today’s entry is mostly just some pictures that try to convince you, once more, that the 1910s laid down a great deal of what we take for granted in films ever since. You may want to turn up your display. We’re going dark.

No sunshine here

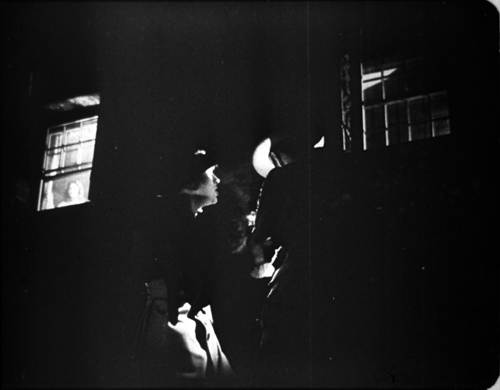

Start with the shot up top, from the independent production A Romance of the Air (1918). Produced by and starring Bert Hall, flyboy and author of the source book, it traces how German spies posing as French refugees win his confidence and try to steal secrets about troop movements. It was released in the month of the Armistice, and it got what appears to be a welcome reaction from audiences.

A Romance of the Air, nearly amateurish in its opening stretches, gets more competent as it goes along. But there’s only one real uptick from a pictorial viewpoint. Two spies have attempted to gas Edith, Bert’s sweetheart, but fortunately their incompetence leads them to the wrong room. They meet outside the house, and suddenly we get a shot that had me hollering.

As the man lights a cigarette, a low-slung angle shows the flare of the match illuminating his hatbrim and the countess beside him. In the upper left Edith peers down from a window. We might be in Hollywood, 1945, perhaps in the hands of production designer William Cameron Menzies or ace DP John Alton.

It’s interesting that a title pops in here, coaxing the audience to notice the face at the window.

The mistaken placement of “From up above” tells you something of the clumsiness of this whole production. Yet bad grammar is redeemed when we return to the framing as the spies twist around in surprise and the man clutches the countess.

Other filmmakers of the period would have trusted the audience to spot Edith, but nonetheless an undistinguished, forgotten film bequeathes us one bold moment.

We can see a more conventional look emerging when characters get sent to jail. By the end of the 1920s, filmmakers had found a way to crosslight cell bars to make them stand out crisply, as here in von Sternberg’s Thunderbolt (1929).

A jail scene in The Unknown (1915) isn’t so flashy, but the concept of edge-lighting the bars is there. If all you wanted was clarity, the naked cell door suffices, but the sidelight makes the barrier more vivid.

At this point, some directors were willing to leave large patches of the image in darkness, even at the risk of off-balance compositions. This is not only expressive; it saves money on set construction. So trust Maurice Tourneur to go further. In Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915), one of the most accomplished films of the era, we get cons as patient silhouettes.

No need to see their expressions; the outlines of their poses express their resignation.

Speaking of prisoners, consider the plight of Ivanoff, the revolutionary who has been sentenced to Siberia in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Man from Home (1914). He has escaped from the mines and taken refuge in a stable. Filing off his chains, he crouches as guards pass by outside. First, he’s in a glare, but when he hears them….

… he shifts into semi-shadow.

The guards’ approach is measured by a barely noticeable change: the gleaming surface on the far left is briefly darkened.

This is a bold instance of “Lasky lighting,” the brilliant effects which DeMille worked up with Wilfred Buckland, Belasco’s stage designer. Several films in my sample exemplify this style, which became part of Jesse Lasky’s Paramount brand. Examples are comparatively abundant because many Paramount films have survived from the silent era.

Camera obscura

In A Romance of the Air, the darkness is motivated as a night scene, and naturally prisons and hiding places are associated with danger. Another option is to stage scenes in darkened rooms, populated by sneaking and skulking characters. Again, the association with criminality is evident. In Alias Jimmy Valentine, hoods hide from cops and are visible thanks to diagonal edge lighting.

More dynamic are two suspense scenes in Madam Who (1918), the story of a plucky Southern belle who goes undercover for the Confederate cause. In the first, disguised as a man, she peers down from a hayloft to watch the meeting of the Sons of the North gang. We get an optical POV shot straight down, and then a close reaction shot, with a fish-hook of light snagging her face as she glances at us.

Reginald Barker, one of the most resourceful directors of the era, didn’t let up in a later scene of Madam Who. Jeanne and the secret agent Henry Morgan get the drop on the Sons’ leader Kennedy. The action plays out in layers of darkness, with her poking a pistol through the doorway right of center, and it’s capped by a stark close-up.

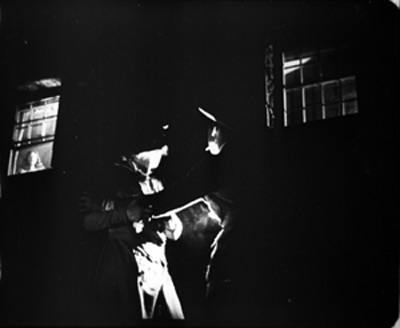

In the late 1910s, several directors use such darkened interiors for fight scenes. In De Luxe Annie (1918), the heroine’s husband takes a brutal beating from the criminal he’s trapped. The accomplice runs to administer a hypodermic.

Something similar happens in The Family Skeleton (1918), when dissolute Billy (Charles Ray) battles the bully who has tormented him throughout the movie.

Shadow-filled rooms help amp up suspense during fistfights. We can’t be sure who’s winning, and the enveloping darkness can also suggest more savage violence than could be shown in normal light.

Or you can stage a fight or a chase in a darkened area outdoors. The Sign of the Spade (1918) sets its climactic abduction and rescue under a seaside pier, and the silhouettes that result would not have shamed Panic in the Streets (1950).

As with the jail in Jimmy Valentine, we have to read the characters’ emotions–chiefly, the desperation of the fleeing woman–from their body language. And as often happens, the more we have to strain to see the action, the more gripping it becomes.

Billy and two Annies

De Luxe Annie (1918).

Of course what we call film noir includes more than visual style. Like many terms in the arts, film noir picks out a cluster concept. It links together distinctive subjects (urban life, abnormal mental states, misogyny), attitudes (alienation, nihilism, malaise, mistrust of authority and the upper class), themes (official corruption, revenge, male friendship and betrayal), plots (investigation, pursuit, deception), narrational devices (flashbacks, voice-over commentary, dreams and hallucinations), and visual techniques. Because noir is a cluster concept, eager acolytes can choose some noir-ish qualities of Film A and declare it a more or less plausible instance, while with Film B a quite different set of features might help it qualify too.

For example, in visual technique, only a few shots of Laura carry traces of the lighting style we think characteristic of noir. But the film does present a decadent, treacherous milieu harboring a mysterious, perhaps dangerous woman who may be feeding a man’s delusions and obsessions. Laura, I’d suggest, counts as a noir on thematic and narrative grounds more than on stylistic ones.

So do we find non-stylistic features of noir in the 1910s? Sometimes, yes. I’ll save my prime example, an intricate and beautiful thing, for an entry of its own. But here are two nifty cases where the visual pyrotechnics spring from noirish narrative and thematic pressures.

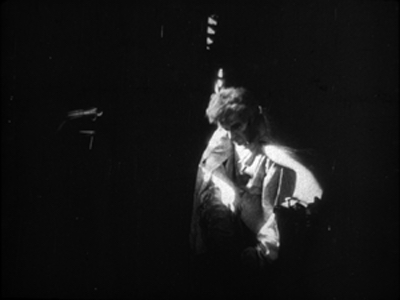

Billy Bates is warned that alcoholism runs in his family, but on getting his inheritance he holds a party and learns that he likes the stuff. Not needing to work, he keeps drinking. He falls in love with chorus girl Poppy Drayton, but when she’s insulted in a saloon he’s too crocked to defend her from the hulking Spider, who beats and shames him. Billy learns that Spider is planning to abduct Poppy and so lays a trap. He waits in Polly’s parlor, resolving to stay sober long enough to defend her. Unfortunately, there’s a decanter of scotch within easy reach….

The Family Skeleton (1918) was touted as a “semi-farcical production” but the semi- parts took alcohol addiction fairly seriously. The popular Ray often played the country-boy underdog, so audiences were probably unprepared to see him as a millionaire twitching from the D.T.’s. The scenes of his drunkenness are truly unnerving, even when the plot is lightened by the revelation that Spider is a detective hired by Poppy to force Billy to man up. Billy does, in the nocturnal fistfight illustrated above. There darkness makes Billy’s ultimate victory more plausible; we can’t really see his winning punches.

In the buildup to the fight, however, we get Billy’s growing anxiety over the scotch across the room. He stares at the decanter.

A cut shows us a condensed mental image: what would happen if he drank the contents. In this hypothetical future, the decanter is empty, and in it we see Spider breaking in and carrying off Polly while drunken Billy lolls helplessly.

As in the hallucinations of The Lost Weekend (1945), the filmmaker has taken us inside the addict’s fantasy.

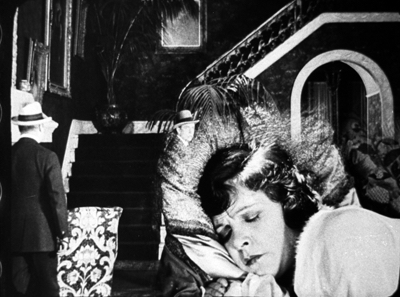

Other subjective effects, like memories and dreams, were common in silent cinema too, though usually not plunged so deeply in darkness. In De Luxe Annie, Julie Kendall is worried that her husband is taking a risk by setting a trap for two dangerous swindlers. He will pose as an innocent mark and then arrest them when they try to con him. Julie’s concern emerges in a virtuoso split-screen dream sequence in which her husband is shot by the crook.

Later in the film, Julie will lose her memory and become the con man’s confederate, the new De Luxe Annie. The screenwriter’s old friend amnesia transforms an upper-class wife into down-at-heel swindler.

What triggers the amnesia? The most remarkable scene in the film. It’s either a brilliant coup or a happy accident, but either way it can stand as proof of the boiling energies of this era.

Worried about her husband, Julie follows him to the site of his trap. She goes in through the basement kitchen and enters almost total blackness. She stands in a tiny pool of light before a big double door, and it opens a crack.

Suddenly, and I mean instantly, the doors are wide open and we get a burst of light.

A jump cut has eliminated the movement of the doors swinging apart. (You can see the splice at the bottom of the second frame and the top of the third.) This is a very bold stylistic flourish.

Kristin suggests that it’s something of an accident. The overhead kitchen light is now lit up, and it was common at the time to cut out some frames when a light source is snapped on. That may be what led to this jump cut, though it’s not clear how anyone in the scene could have hit the power switch. In any event, the force of the cut is amplified by the ellipsis; the doors simply pop open.

Another pictorial surprise emerges when Julie moves a bit and it’s revealed that her figure has blocked De Luxe Annie, who’s facing her over the threshold. They start to grapple with one another and move into darkness on the right.

Annie runs off, but Jimmy the con man is fleeing too, and he shows up to wrestle with Julie. A slamming axial cut shows him punching her fiercely in the head. The edge lighting here is remarkable.

Jimmy gets away, leaving Julie to stagger out and into the fog. She’s contracted amnesia. Later she’ll meet Jimmy again and become his new partner in crime.

This scene is even replayed as a brief flashback, when the original Annie recounts to Jennie’s husband the clash that led to Julie’s disappearance.

This is presented in a more unsurprising way, since there’s nothing new to be learned about the fight. The shot shows the full swinging open of the doors and a clearer revelation of Annie’s presence.

All this won’t be news to aficionados of silent film, who are well aware that the 1910s, and then the 1920s, burst with ingenious creativity. But everybody needs reminding, and the rare films I was lucky enough to study are just part of a huge corpus. The official classics by Chaplin and Griffith and others can be restored and reissued again and again, and we’re grateful. Yet if they’re the peaks of a landscape, there are plenty of luscious valleys that remain unexplored.

Problem is, most of the films from which my scenes come are incomplete, often missing entire reels. So they’ll probably never be screened much, or made available on DVD or streaming services. This is why archives remain indispensable to keeping the entirety of our film heritage, fragments and all, available to researchers. It’s also why I wrote this entry, to share with you my enjoyment of films you may never have a chance to see.

More broadly, scenes like these help us nuance our thinking about those films we do know well. For one thing, they indicate just how rich the creative energies of the 1910s were, and how many options were not embraced by…oh, let’s say for example D. W. Griffith.

For another thing, if these neglected works throw up willy-nilly an alcoholic’s hallucinations, an anxious wife’s dream, a plot based on amnesia, and a strategic replay of a crucial scene, we ought to think twice about claiming that such storytelling strategies are somehow unique to film noir, or the zeitgeist of the 1940s–or our movies today, which continue to use them.

American commercial cinema has drawn on particular themes, plot structures, formal designs, and narrational strategies again and again throughout the decades. My book Reinventing Hollywood floats the claim that silent-cinema narrative devices like flashbacks and subjective sequences went somewhat quiet during the 1930s but were brought back fortissimo in the 1940s, when sound techniques could raise them to a new level of intensity. And I’ve been at pains to argue over the years that we still encounter them.

Again, no surprise once we think about it. This is just history at work: the continuity of a powerful, proven storytelling tradition. Once we’ve learned to love darkness, we can’t give it up.

Again I must give my thanks to the John W. Kluge Center for providing me a long stay at the Library of Congress. The Moving Image Research Center was my host, and so I’m grateful to Mike Mashon, Greg Lukow, Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, and Rosemary Hanes. They’re doing their utmost to preserve our film heritage.

For information on the survival of US silent films, download David Pierce’s indispensable study, done for the Library of Congress. The information on Paramount is on p. 41.

Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85. She discusses American lighting practices of the period in The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), 223-227. In the same volume in discussing film noir I consider the established practice of chiaroscuro for scenes involving crime and mystery (p. 77).

The most in-depth account of Paramount’s lighting styles is Lea Jacobs’ article “Belasco, DeMille and the Development of Lasky Lighting,” Film History 5, 4 (December 1993), 405-418. This is a good place to record my deep debt to Kristin, Lea, and Ben Brewster, for years of tutelage in what makes the 1910s so important.

There are many good books on film noir, but the most comprehensive reflection on the category’s many implications is James Naremore’s More Than Night: Film Noir and Its Contexts, 2d ed. (University of California Press, 2008).

For more on 1910s film style, see this video lecture and this category of blog entries. I talk about other forays into the LoC collections here and here.

Lately, two video distributors have brought out less-known films from the period. There’s DeMille’s The Captive (1915) from Olive, and Irvin Willat’s Behind the Door (1919). The somewhat noirish frame below is from the latter. Flicker Alley, whose commitment to silent cinema from all countries has been extraordinary, deserves our thanks for making the San Francisco Silent Film Society’s restoration of this sensational, and sensationalistic, film available. For more on this restoration, visit the Flicker Alley site.

Behind the Door (1919).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

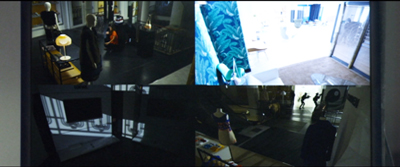

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.

Wisconsin Fim Festival: An unexpected gem, a Zucchini, and a farewell

Clash (2016)

Kristin here:

Three more films from this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival.

Clash (Eshtebak, 2016)

David and I were intrigued by the festival’s program notes describing Egyptian director Mohamed Diab’s second feature, Clash, as taking place with the camera entirely confined to the interior of a police paddy-wagon. This kind of limitation can be a fruitful device, as it was in the Israeli film Lebanon; there the action took place inside a military tank. Clash turned out to be a real discovery, the best film I saw at the Festival (putting aside A Quiet Passion, which we had already seen at the Vancouver International Film Festival.).

Diab’s paddy-wagon has the advantage of rows of barred windows and a door, so that we can frequently see what’s happening outside. The film is set in the summer of 2013, when there were protests, often turning violent, in the wake of the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi and his replacement by the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The truck moves through Cairo, encountering waves of such protests, and it gradually fills with a collection of people with various religions, beliefs, and cultures–supporters of Morsi’s party, the Muslim Brotherhood; others who oppose him; Christians; a homeless man; a nurse; and two journalists–with arguments and violence erupting inside the vehicle as well as outside.

Diab had to tread a fine line in his depiction of these people, since his basic theme is that they all must learn to cooperate to some extent if they hope to survive the baking heat, tear gas, gunfire, police bullying, and the anger of the mobs outside the truck. Officially the Muslim Brotherhood is considered a terrorist organization in Egypt, though Diab manages a fairly even-handed treatment of its members and supporters. Remarkably the censors did not require any changes to the film.

Just as remarkably, Diab was able to stage huge, convincingly terrifying riots in Cairo’s streets and highways (above). In a brief interview at Cannes last year, where Clash was shown in the Un Certain Regard section, he was asked if the shoot was difficult.

Very. You are risking your life because people might mistake the shoot for a protest, or might mistake you for the police. And there are haters of both, who can shoot you. It took us months of preparation. Egyptians to whom I’ve shown the film are blown away because they know that what we did is almost impossible.

He makes similar remarks in a question-and-answer session at the London Film Festival; his discussion of the film’s techniques comes from about 9:30 to 13:50.

The characters in the truck are constantly in danger, both from each other and from the rioters, and the action is absolutely riveting. There are a few lulls to vary the pace and to allow the prisoners to deal with their wounds and try to work out a strategy to protect themselves, but otherwise the suspense is maintained at a high level. A climactic scene in which rioters attack the truck, flashing laser pointers into it and trying to tip it over is handled, as Variety‘s review put it, with “brilliantly choreographed pandemonium.”

Clash was a huge success in Egypt. It was released in France in September and is already out on region 2 DVD (French subtitles only) there. Its festival life seems to be drawing to a close. It’s due for theatrical release in the UK and Ireland on April 21 and presumably will come out on Blu-ray and/or DVD. You can get a good sense of the film from the online trailers, the European one and especially the Egyptian one, though the film is not nearly so fast-cut.

My Life as a Zucchini (Ma vie de courgette, 2016)

2016 was a good year for animation. Kubo and the Two Strings, The Red Turtle, Moana, and Finding Dory were excellent as well. (I thought Zootopia was overrated.) Add My Life as a Zucchini to that list. This being Madison and the Wisconsin Film Festival being a university-sponsored event, we saw it with French subtitles rather than dubbed.

The style of the film, with its bright colors and cute, big-headed characters (above and at the bottom), makes it seem aimed at children, and the story is presented almost entirely through the viewpoints of Zucchini and the other children he meets. Yet children younger than teenagers would probably find parts of it incomprehensible or disturbing. The boys indulge in naïve but somewhat explicit speculation about sex. Zucchini’s beer-swilling mother apparently dies in an accident that he inadvertently causes, though this happens offscreen. He is taken by a sympathetic policeman to a small home for young children in the countryside. Not all are orphans, as it is made clear that one girl was taken away from her sexually abusive father and some of the others come from homes ruined by addiction or violence. Zucchini gets bullied and teased before finally being accepted.

All this makes for a strain of melancholy running through the film, but there is considerable humor to counter it, and the ending is happy.

Like Kubo, My Life as a Zucchini is puppet animation. Clearly it was done on a much lower budget, without the laser-printed changeable faces that make Laika’s characters so expressive. Charmingly, if distractingly, the clothes of the puppets occasionally shift positions, betraying the handling by the animators between frames–as when the red star on Zucchini’s T-shirt inadvertently takes on a life of its own. But on the whole, the filmmakers have used simple means to give their figures considerable expressivity.

The nomination of My Life as a Zucchini for the Best Animated Feature Oscar came as something of a surprise. Foreign films do show up in that category, but this one had its widest American release in a mere 53 theaters. It came out on February 24 and is still in 22 theaters, having grossed $286,154 as of April 6. (Presumably that does not count the two WFF screenings; the one we went to was sold out.) The DVD and Blu-ray versions are available for pre-orders on Amazon. The description says that both the original French-language soundtrack and the English-dubbed one are included.

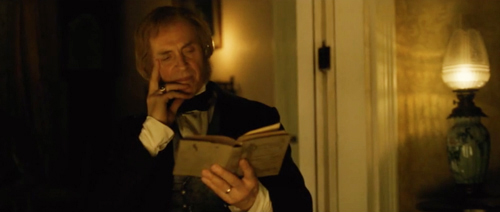

Afterimage (Powidoki, 2016)

Afterimage premiered at the Toronto Film Festical almost exactly a month before the death of director Andrzej Wajda. It deals with the co-founder of Polish Constructivism, Wladyslaw Strzeminski, who helped create the Blok group in Warsaw in 1923. The plot covers only Strzeminski’s last years, but we get a strong sense of his entire career through gallery scenes displaying his work.

Socialist Realism was imposed upon Polish artists after the country came under the sway of the USSR in the wake of World War II. The film’s action starts with Strzeminski’s being fired in 1950 by the Ministry of Culture and Art because he refused to adhere to the doctrine. We see his stubborn resistance and the attempts by his adoring students to help him find respect and other work. Up to his death in 1952, he is oppressed by intransigent officials bent on denying him even the most demeaning jobs.

Reviewers have treated Afterimage with the respect due a veteran auteur late in a six-decade-plus career, but they deem it to lack the energy and appeal of his earlier work. Certainly compared with Wajda’s films of the 1950s and 1960s (we’ve commented briefly on two from the 1960s), Afterimage is a fairly conventional film. It’s beautifully made, as Wajda clearly had a considerable budget to recreate the historical look of Soviet-era buildings and streets of the early 1950s. To anyone unfamiliar with the impact that Socialist Realism could have on the avant-garde artists in the USSR and elsewhere starting in the 1930s, the film provides a vivid example. The film also contains an excellent performance by Boguslaw Linda, perhaps best known as the lead in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance.

Strzeminski, being the victim of persecution from almost the beginning, automatically becomes a sympathetic character. He also lost an arm and a leg in 1916 during World War I. (The budget is on display again in the fact that undetectable special effects removed Linda’s own arm and leg.) It is hinted that if he had been grievously injured in World War II, some allowances might be made, but having it happen during the Tsarist war of the pre-revolutionary era earns him no credit with the officials.

Yet Strzeminski loses some of our sympathy through his treatment of his teenage daughter Nika. She is interested in his art, closely examining the “Neoplastic Room” he helped create in the Lodz Museum–just before it is dismantled and put into storage as part of Strzeminski’s punishement. Nika also tries to help her father, cooking for him and trying to get him to cut back on smoking, but his ingracious rejection of her efforts helps drive her to live in a girls’ dormitory near her school. He remarks matter-of-factly after Nika leaves, “She will have a hard life.”

Our thanks to Graham Swindoll of Kino Lorber for help with this entry. As well, of course we owe a debt of gratitude to the WFF programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

My Life as a Zucchini (2016)

Wisconsin Film Festival: Sometimes a camera movement . . . .

A Quiet Passion (2016).

DB here:

. . . . sums up what has happened and hints at what’s to come.

Seeing Terence Davies’ splendid A Quiet Passion again at our Wisconsin Film Festival brought out several subtleties I hadn’t registered on my first pass last year at Vancouver. Among the things I appreciated was a poignant 360-degree-plus tracking shot in the Dickinsons’ parlor.

This poet’s passion isn’t always so quiet. Davies’ earliest films are notably light on dialogue, but this one contains plenty of talk, both bantering and brutal. Perhaps most surprisingly, the supposedly withdrawn Emily Dickinson engages in snappy and snappish exchanges with friends, family, neighbors, and one awkwardly sincere suitor. All the more striking, then, when Davies halts the talk and gives us a suite of images accompanied by discreet sound effects, music, and voice-over portions of Dickinson verse.

Fairly early in the film, we get a spirited exchange between the censorious Aunt Elizabeth and the Dickinson family. After her indignant reply to their mock-heathen teasing, she gulps down some currant wine. Next we see the family quietly sharing an evening. That’s when we get this ripe circular camera movement.

It starts framing Emily, reading by firelight. She looks left.

As the camera coasts past Emily we get a glimpse of a fond smile. The moving frame reveals Aunt Elizabeth, struggling to keep her eyes open.

In the course of this movement, over the soft crackling of the fire and a ticking clock, we hear the older Emily’s voice-over reciting.

The heart asks pleasure first,/ And then, excuse from pain;/ And then, those little anodynes/ That deaden suffering.

The poem is a famously puzzling one. Is the speaker suggesting a bargain–if not pleasure, then no pain, please? Or is it a description of the course of a life: youth seeking pleasure, old age willing to accept absence of pain, and in the end a plea for something that simply ends suffering? The juxtaposition of young Emily and aged Elizabeth suggests two phases of woman’s life: Is Emily still pledged to pleasure (of a bookish kind) while her aunt is already seeking an anodyne, like the brandy she greedily gulped and the sleep that seems to be stealing over her?

As the camera passes Aunt Elizabeth, the poem is completed.

And then, to go to sleep;/ And then, if it should be/ The will of its Inquisitor,/ The liberty to die.

Elizabeth’s drowsiness comes to prefigure the death that will haunt the rest of the film. And the poem’s grim acceptance of physical decline, lifted by the mercies of death, sketches what will be all too vivid in scenes to come.

The camera continues its leftward survey of the family circle, settling next on Emily’s father Edward. He’s thoughtfully reading. So is brother Austin, at the rear table. Sister Vinnie, though, is sewing at the same table.

This survey of the immediate family shows Emily, like the men, gone all literary, while good-hearted Vinnie does no reading, instead attending to women’s tasks. The shot identifies Emily as, if not unfeminine by the standards of the day, at least not sunk in domesticity. She may be searching for that literary spark she will so often identify with glimpses of Eternity.

The view of Edward has been accompanied by clock chimes, and under the image of Austin and Vinnie we hear the clock start to strike the hour of nine. As the camera moves leftward, we see the mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson.

Neither reading nor tending to domestic tasks, Mrs. Dickinson is staring raptly into the fire. Everyone is in a kind of reverie, but hers is inward and melancholy. In the previous scene she has told Aunt Elizabeth “I prefer to listen and remain silent.” Later in the film we’ll learn that she has gradually withdrawn from the family, as if feeling ill-adjusted to these intellectuals, or through some private unhappiness. Later in the scene we’ll get another hint, but after briefly lingering on her, now the camera moves to the fire and then passes beyond.

The piano will be the site of a crucial conflict to come, and the wine decanter, already featured in the scene before, will later be one index of the self-righteousness of the new clergyman’s wife. This “empty” stretch becomes a caesura before we get to the simple, devastating final image of the shot.

So much for books. Emily’s plaintive look, not clearly fastened on any family member, is ambivalent. Has the camera traced her eyes around the family circle, as her sidewise smile at Aunt Elizabeth suggested earlier? If so, what has moved her? Her mother’s solitude? Her siblings’ and fathers’ obliviousness to the older woman? Or is it something more self-centered? Locked within the family circle, has she surveyed the perimeter of her life to come?

The question is partly, teasingly answered, when we hear the offscreen voice of Mrs. Dickinson. She asks Emily to play one of the old hymns. Emily rises and goes to the piano, and we get a cut to the shot surmounting today’s blog entry. After Emily starts playing, the rest of the family is forgotten, and Davies cuts to a closer view of her mother.

Still staring into the fire, she speaks of hearing the hymn sung by a young man with a beautiful voice. He was only nineteen when he died, she tells us, or maybe just herself. The softly delivered memory carries more than mere nostalgia. Are the others even noticing? We never find out.

Unlike her husband and children and Aunt Elizabeth, the mother ponders the past and its losses. We’re invited to imagine an alternative life for her, perhaps with the beautiful young man. Is he kin to the young woman in white with the parasol recalled by Bernstein in Citizen Kane, as he stands before his roaring fire? At the least, this warm parlor is now haunted by death.

Davies is too tactful to push this moment, leaving the character to keep her own counsel. But I can’t resist another probe. The Magnificent Ambersons is one of Terence’s favorite films, he told us during his visit (“better than Kane“). It’s not a stretch to let the image of Mrs. Dickinson remind us of the somber shot of Major Amberson before another fireplace. Deprived of his fortune, baffled by all around him, he ponders the origins of life as the narrator muses that even an Amberson might not get a leg up in the Hereafter.

Terence pointed out to us that the great American films are often about families, because in that setting passions are both aroused and contained. The Dickinson family, tightly bonded by love and respect, ruled by a tender but iron-willed patriarch, harboring a mother and daughter withdrawn from the world, split by failed marriages and angry reproaches, prey to death and broken pledges, is no perfect haven. Perhaps Emily’s stabbing epiphany is a realization of all of that, and what it might mean for her art. All this takes two minutes and ten seconds.

Nowadays the circling camera is a cliché; characters sitting around a table or even just standing in the street seem to be spinning on a turntable. Davies is far more discreet and precise. Step lightly on this narrow spot, a Dickinson poem advises us, and that’s what his camera has done here.

Thanks to Bianca Costello and Music Box Films, which is distributing A Quiet Passion. Its US rollout starts 14 April. Thanks as ever to the Wisconsin Film Festival and its plucky programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

And many thanks to Terence Davies for coming to town and providing fine conversation about George Butterworth, Meet Me in St. Louis, and the making of A Quiet Passion. As he told our audience: “I hope you enjoy it, and if you don’t, complain to Mr. Trump.”

Other entries in the intermittent Sometimes. . . . series are here (I Topi Grigi), here (The Mormon’s Victim), here (A Touch of Zen), here (Side Street), and here (Frisco Sally Levy).

Kristin and Terence Davies.