Archive for August 2017

Venice 2017: Early days

DB here:

After the triumph of Rosita (more on that to come), the first full day of the Biennale launched with several press screenings and press conferences. The opening conference featured Festival President Paolo Baratta (below), Director Alberto Barbera, and jury heads including Annette Bening (below), Benoît Jacquot, and John Landis (below).

During that session, two subjects recurred: Netflix and Virtual Reality. Some Netflix films are playing out of competition: Our Souls at Night, with Robert Redford and Jane Fonda (who will get honorary Golden Lion awards); and Netflix’s first Italian production, Suburra. In addition, the Mostra will show all the episodes of Errol Morris’s Netflix series Wormwood. Barbera remarked that festivals must follow where auteurs lead. Now that so many filmmakers are directing telefilms and series “with the same attitude” they employ in theatrical features, festival progamming must take notice.

Similarly with VR. Baratta pointed out that this medium is now being used by artists, and Venice has a historical and aesthetic obligation to keep up with moving-image explorations. Barbera added that for him VR was not the future of movies; it’s a new medium that will exist alongside them. Just as film didn’t kill theatre and television didn’t kill film, VR is likely to flourish on its own. It will likely have its dedicated venues, such as MK2’s VR theatre in Paris and similar spots in Amsterdam.

Similarly with VR. Baratta pointed out that this medium is now being used by artists, and Venice has a historical and aesthetic obligation to keep up with moving-image explorations. Barbera added that for him VR was not the future of movies; it’s a new medium that will exist alongside them. Just as film didn’t kill theatre and television didn’t kill film, VR is likely to flourish on its own. It will likely have its dedicated venues, such as MK2’s VR theatre in Paris and similar spots in Amsterdam.

John Landis admitted that he was intrigued by VR and wanted to learn how to use it. Can it tell a full-length story? (Most VR pieces are short and situation-bound.) Can it focus the viewer’s attention—a key component of traditional visual narrative? Landis noticed that his experiences of VR gave the viewer great freedom of when and where to look. Could storytelling harness that freedom? It was good to see a filmmaker pondering these basic issues.

We saw the first screening of Alexander Payne’s Downsizing, a sharp and heartfelt satire on consumerism and ecology. Matt Damon and Kristen Wiig play a couple who decide to take advantage of a new technology that shrinks humans to 5-inch heights, and thus allows them to live more cheaply and reduce the strain on the planet.

The situation takes several unpredictable turns and in the face of impending disaster veers into a Capraesque optimism. Yet there’s a somberness here too, perhaps most akin to that in About Schmidt. Alexander mentioned Chekhov as an influence, and he admired the writer for realizing that emotional effects stand out against “a cold background.” The clinical scientific milieu of the downsizing operation and the arid cheerfulness of Leisureland, a sort of micro-EPCOT, provide that backdrop for the problems facing tiny Matt Damon.

In the press conference, Damon called Alexander’s direction meticulous and “sure-handed.” That shows in the film: No bouncy-camera grab-and-go, but precisely staged scenes. One sequence, that showing the medical mechanics of the downsizing process, is shot for shot as cogent and engaging a stretch of cinematic storytelling as I’ve seen in a long while. There’s also a good gag when Damon wakes up from the surgery and immediately…well, I can’t spoil it. Below, here are Jim Taylor, co-screenwriter; actor Hong Chau, who plays a Vietnames dissident; Payne; and Damon.

Our old friend Mark Johnson produced the film. It was encouraging to see the huge press turnout and the excellent reviews (Variety Hollywood Reporter, The Wrap) that Downsizing got. It goes immediately to Toronto.

Thanks to Peter Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michela Lazzarin, and all of their colleagues for inviting and assisting us.

We have a blog entry devoted to Alexander Payne here, where he mentions his and Jim’s long-germinating plans for Downsizing. Kristin compares his work to Chekhov there too.

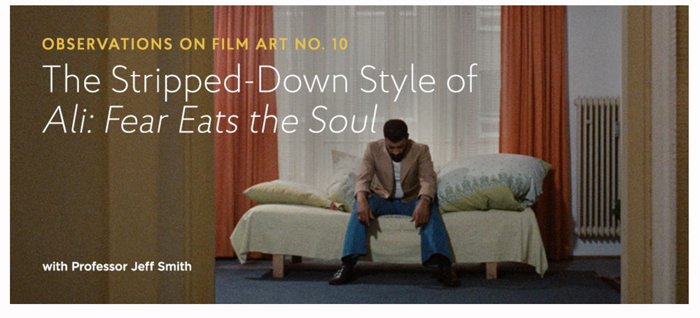

Fassbinder’s figures: Jeff Smith on ALI: FEAR EATS THE SOUL

DB here:

Normally our co-conspirator Jeff Smith would be guest-blogging to fill in background on his new installment on the Criterion Channel. That entry is devoted to Fassbinder’s great social melodrama Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. But Jeff is ramping up for the start of a semester, and we’re hustling to get ready for a trip, so let this notice do duty.

In this month’s entry, Jeff digs deep into Fassbinder’s directorial style and shows how it connects to the film’s portrayal of bigotry–ethnic, racial, age-related. Since at least Katzelmacher (1969), and right up to Querelle (1982), Fassbinder was constantly experimenting with performance and staging. Ali is one of his triumphs. Jeff is especially acute, I think, in showing how before-and-after parallels in the drama emerge from shrewd repetitions of compositions and mise-en-scene. Thanks to the boffins at Criterion, these become crystal-clear through judicious split-screen.

Jeff’s entry is one of our very best, and we hope subscribers to FilmStruck and the Criterion Channel will enjoy it. The transfer is very pretty too. Coming up in future months: entries on M, The Phantom Carriage, Brute Force, and Chungking Express.

As for Kristin and me, we’re off to the Venice International Film Festival. Peter Cowie has kindly invited me to be on the panel devoted to discussing the projects in the Biennale College Cinema 2017. From the press release:

“The thirteen feature films already produced and screened during the first four years of the Biennale College Cinema program have met with acclaim throughout the world. Produced on an ultra-modest budget, each of them showed an unusual talent and an innate gift for filmmaking,” notes moderator Peter Cowie (film historian and former Int’l Publishing Director of Variety). “The Biennale College Cinema scheme is exciting chiefly because it is in essence a workshop – a workshop and laboratory that places the focus squarely on two essential themes: the making of low-budget films in a period of global recession, and the need to find youthful auteurs if the cinema is to be reinvigorated.” The laboratory was created by the Biennale di Venezia in 2012 and is open to young filmmakers from all over the world.

This is very exciting. And while we’re in Venice, we hope to reconnect to old friend Mark Johnson (producer of innumerable outstanding films, including Rain Man, Logan Lucky, and Galaxy Quest) and newer friend Alexander Payne. They’re arriving with Downsizing. Many other major films will be there, and we hope to report on some of them here over the next two weeks. And then there’s some scary Virtual Reality….

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their teammates at Criterion. A complete list of the Observations on Film Art series (ten already!) is here.

Videos of earlier Biennale College Cinema panels can be found here. Glenn Kenny discusses last year’s event on RogerEbert.com.

Our own efforts at split-screen analysis yielded a comparison of the murder and its replay in Mildred Pierce. You can see that here, and the accompanying blog entry here.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.

Is there a blog in this class? 2017

Kristin here–

As each fall semester looms, we provide you with a rundown of entries on our blog that might be useful to teachers and students. They also can be handy for other readers who want to check whether they have missed some entries that might interest them.

We started this blog nearly eleven years ago partly with the idea of providing supplementary material that might be of use to teachers who assign our Film Art: An Introduction textbook. But we don’t make any attempt to tie our entries to the textbook. Each year, however, we naturally deal with film techniques, formal strategies, stylistic choices, norms and transformations of them, and genre conventions, and some of these could be useful in teaching or preparing lectures for specific chapters of Film Art.

We haven’t listed every post, but you can find more by using the very efficient search engine or the many categories listed on the right-hand side. You can also see previous entries in this series here: 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016.

Multiple chapters

“DUNKIRK Part 1: Straight to the good stuff” and “DUNKIRK Part 2: The art film as event movie.” These two entries discuss aspects of Christopher Nolan’s film. The first talks about Dunkirk’s minimal exposition, which would be relevant to Chapter 3 (Narrative Form), and the color scheme, which would relate to chapters 4 and 5, on Mise-en-Scene and Cinematography. The second part deals with its genre, as a mixture of the war film and thriller (Chapter 9); it also looks at the film’s temporal scrambling, which relates to Chapters 3 and 6 (Editing).

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

“Replay it again, Clint: Sully and the simulations” considers some ways of creating complex story-plot relationships, particularly through flashbacks that replayt events. It concentrates on recent Clint Eastwood films and especially Sully.

In “ARRIVAL: When is now?” David looks at that rare phenomenon, the flashforward. He concentrates on Denis Villeneuve’s science-fiction film and its challenges to the viewer.

We have a sneaking suspicion that many teachers will be teaching La La Land. It would work as an accompaniment to several of our chapters in Film Art (narrative, sound, genre, etc.). We’ve blogged about it three times this year. In “How LA LA LAND is made,” we analyze the narrative structure and how the songs fit into it (as well as following the classic template of the Broadway musical).

“Fantasy, flashbacks, and what-ifs: 2016 pays off the past” offers a study of depth of narration, particularly in films where our knowledge of the action is largely restricted to that of a single character’s. In some cases there is presentation of the character’s subjective thoughts and memories. Lots of recent films furnish examples.

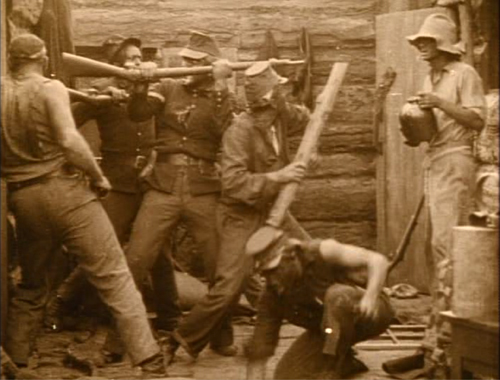

“Anybody but Griffith.” This post also deals with staging, but specifically with a type of staging, often quite elaborate, that was used largely in the period from 1908 to 1920. It depended on sustained takes rather than editing and on the actors’ precise gestures and shiftings of position. David has written quite a lot about it as the “tableau” style. Useful for advanced students or if you’re teaching or studying silent cinema.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

“My girl Friday, and his, and yours” is about His Girl Friday. The first section examines the historical sources of the title phrase, while the second part deals at some length with subtleties of staging, both in depth and across the frame.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

“Wisconsin Film Festival: Sometimes a camera movement …” offers a close study of a single long-take 360-degree panning movement in Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion.

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

“Action and essence: Kurosawa’s SANSHIRO SUGATA on the Criterion Channel” examines the “axial cut.” It’s an editing technique that cuts closer and closer to (or, rarely, further away from) its subject straight along the axis of the lens, without a change of angle. It may sound obscure, but it’s actually commoner than you might think. Even The Simpsons uses it occasionally.

“Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it” examines crosscutting in some recent films.

“Camera connections: RED on FilmStruck: A guest post by Jeff Smith” looks at cinematographic style in Krszystof Kieslowski’s Three Colors: Red.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

“Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT” analyzes how the musical score of Hitchcock’s film fits into the film’s narrative progression.

“Oscar’s Siren song 3: a guest post by Jeff Smith” examines the wide variety of approaches used in the musical scores of the 2016 Oscar nominees for best score.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

“Going inside by staying outside: L’AVVENTURA on the Criterion Channel” examines stylistic changes in Michelangelo Antonioni’s films, particularly relating to staging.

Chapter 9 Film Genres

“LA LA LAND: singin’ in the sun” has three guest experts on musicals discussing the conventions and innovations of La La Land.

For those who teach film noir (and quite a few of you do) might want to look at “Film noir, a hundred years ago.” It gives numerous examples of “film noir” lighting in films of the 1910s. This could also be used for low-key lighting in Chapter 4.

“Thrill me!” discusses the recent prevalence of the thriller movie, even among art-cinema directors.

“MONSIEUR VERDOUX: lethal lothario” treats Chaplin’s film as belonging to the serial-killer genre.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

“Murnau before NOSFERATU” could be useful in teaching the silent-German section of this chapter or if you show any early Murnau film. There’s nothing on Expressionism but quite a few examples from major German films of the late 1910s and early 1920s, primarily the restored Der Gang in der Nacht (1921).

“The ten best films of … 1926” is the latest in our annual attempt to call attention to the classics of the silent era, both famous and obscure. This year’s list covers several countries’ films, including Japan for the first time.

Miscellaneous

If you supervise dissertations or are writing a book yourself, you might be interested in seeing how David went about researching his forthcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood. Complete with exciting photos of boxes of file folders. See his “Oof! Out!”

Every now and then we post a wrap-up of recent DVDs and Blu-rays. “Silents nights: Stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings, the sequel” concentrates on two releases, one a beautiful restoration of a well-known classic and one a rediscovery of a Native-American feature.

“OBSERVATIONS goes all FILMSTRUCK.” For those of you using the rich foreign and indie offerings of streaming service FilmStruck for teaching, class preparation, or personal pleasure, we have an introduction to our contribution to the supplements thereon. Our series of introductions to films, “Observations on Film Art” is, as its name suggests, a sort of extension of this blog. We do close analysis of a specific topic in one or two films, complete with more clips than we could possibly use in our entries here.

Finally, if readers, teachers, and students are curious about how Film Art came to be written, that comes up in our SCMS interview with Charlie Keil, linked in this blog entry.

Arrival

DUNKIRK Part 2: The art film as event movie

Dunkirk (2017).

DB here:

In some ways Christopher Nolan has become our Stanley Kubrick. Many directors have found ways to turn genre movies into art films; think of Wes Anderson and comedy, or Paul Thomas Anderson and melodrama. But seldom does the result become both a prestige picture and an event film.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Like Kubrick, Nolan moved from the independent realm to an assignment (Insomnia) before being entrusted with a big picture, the first of the Batman reboots. As he developed the Dark Knight trilogy, he made two films in the one-for-them, one-for-me mode (The Prestige, Inception). But Inception became his 2001, a genre hybrid (science-fiction/heist film) that proved that he could turn an eccentric “personal” project into a blockbuster. After The Dark Knight Rises, Interstellar showed that he could make an original genre film that was both prestigious (brainy, based on real science) and an event film. He became another director you want to be in business with. Warners obliged.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

True, Kubrick the former photographer is the more fastidious stylist. You can’t imagine him accepting that his film could be shown in three aspect ratios (as Dunkirk is). The Prestige shows that Nolan can be a precise pictorialist, but as I argue in our little book on his work he’s usually looser at the level of composition and cutting. What he’s interested in above all is narrative.

It’s rare to find any mainstream director so relentlessly focused on exploring a particular batch of storytelling techniques. Like Resnais, Godard, and Hong Sangsoo (a strange crew, I admit), Nolan zeroes in, from film to film, on a few narrative devices, finding new possibilities in what most directors handle routinely. He seems to me a very thoughtful, almost theoretical director in his fascination with turning certain conventions this way and that, to reveal their unexpected possibilities.

Specifically, I think, he’s interested in subjective storytelling, and how it interacts with a very traditional film technique: crosscutting. And he manages to make both fit within a genre framework.

Take Dunkirk. Spoilers ahead.

Field-stripping the war movie

In working on Reinventing Hollywood, I came to realize that the war film bristles with a lot of narrative possibilities. You can focus on a single protagonist, as Sergeant York and Hacksaw Ridge do. Or you can spread the protagonist function to two pals, three comrades, or an entire unit. Mission-team movies like Desperate Journey or The Guns of Navarone can be tightly plotted, but films about ongoing combat can be more episodic, stressing the long slog (The Story of G.I. Joe) or the need to respond to more or less random attacks (Battleground). In most variants, battles and strategy sessions alternate with relatively dead time when the grunts ponder their fate and talk about life back home. Letters from mom or photos of wives and girlfriends are a must.

One popular subgenre is the Big Maneuver movie. In The Longest Day the Allies’ landing at Normandy is given as a panorama across nations and a trip through the military hierarchy. The viewpoint sweeps from top brass on both the Allies’ and Axis side to lower-down infantrymen, partisans, and ordinary citizens. Although A Bridge Too Far stresses the generals’ debates about what turns out to be a failed strategy, it too spends time on lower-echelon officers.

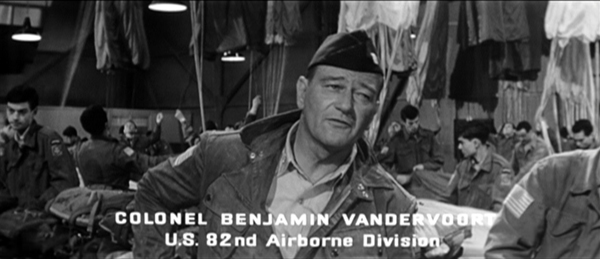

In the Big Maneuver movie, certain scenes are conventional. We see briefing rooms fitted out with maps and models of the terrain. Because the cast is vast, officers are sometimes distinguished by titles (as well as being played by instantly recognizable stars).

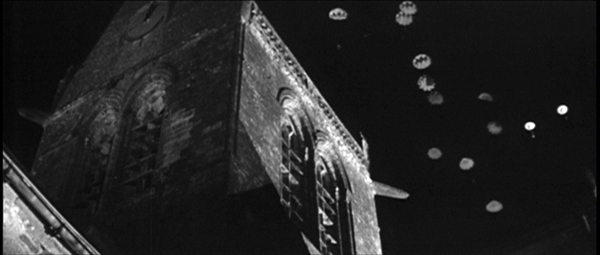

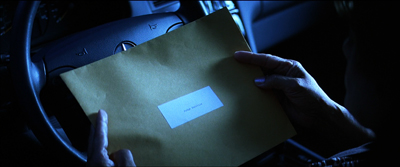

And when the film’s narration shifts to the grunts, we get quick characterizations that invoke their pasts. Early in The Longest Day, a rosary in an envelope reminds paratrooper Schultz of an incident at Fort Bragg.

Later in the film we’ll find out what this incident was, and what it says about his character.

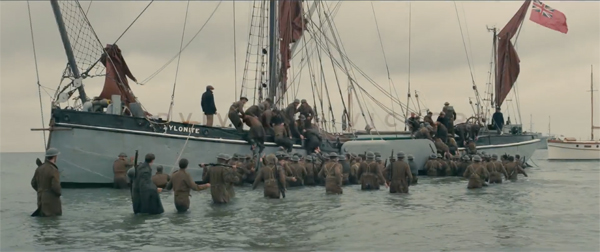

As many critics have noticed, Dunkirk adopts the framework of the Big Maneuver war movie but it strips away many of these conventions. The only map we can examine, as Kristin mentioned, is the one on the leaflets the Germans are circulating, and for our protagonist the leaflets’ biggest value is as toilet paper. Commander Bolton and Colonel Winnaut are the only brass we see, apart from a brief visit from a Rear Admiral. More important, they’re in the thick of it, not in some safe HQ reading dispatches and pushing toy ships around tabletops.

Just as important, Nolan has purged the characters of backstory. Tommy, Farrier, pilot Collins, the French boy posing as Gibson, and Alex, the angry soldier who attaches himself to Tommy, aren’t given family or memories, nor do they display tokens of home. We don’t even know how Tommy got those scars on his knuckles. Only Mr. Dawson has a bit of a past, and that’s given us late when we learn that his son, an RAF pilot, was killed–thus giving extra motivation to his patriotic urge to help in the evacuation.

While critics complained of too much exposition in Inception, now Nolan gives almost none. In one sense, this laconic presentation is characteristic of the blank spaces we find in “art films,” where character motivation and psychology are often obscure. This is, by Hollywood standards, certainly a sparse war picture. Yet Nolan has spoken of this strategy as reworking a familiar structure. His film, he says, is all climax.

For me, this film was always going to play like the third act of a bigger film. There have been films that have done this in recent years, like George Miller’s last Mad Max film, Fury Road, or Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, where you’re dealing with things as the characters deal with them.

Kristin’s previous entry points out that in her model of classical plot structure, the film is actually both a Development and a Climax–that is, parts three and four. A Development section consists of obstacles and delays, which comprise most of the action of this film before the climactic bomber attack. Still, Nolan’s point is well-taken. In most climax sections (third acts), we know everything we need to know about the action. All the relevant motivations and backstory have been supplied in the earlier stretches, so we can concentrate solely on what happens next. In Dunkirk, we don’t see those prior sections, so we’re plunged into the prolonged suspense characteristic of climaxes.

The war movie as thriller

Granted, suspense is an ingredient of any war picture. Alongside GHQ debates about strategy, the Big Maneuver movie includes episodes aiming at momentary tension. The dive into the French village in The Longest Day offers the painful spectacle of men being shot down like a flock of geese, while A Bridge Too Far shows Urquhart (Sean Connery) trapped in a Dutch household as Nazis surround him.

Nolan’s strategy, though, is to make virtually the entire film an exercise in suspense. He understands that pure suspense doesn’t require us to like or even know a lot about the characters. We can feel tension in relation to characters we don’t like (e.g., Bruno’s reaching for the lighter in Strangers on a Train) or characters we don’t know much about at all.

Dunkirk offers a cascade of primal dangers, an anthology of narrow escapes and last-minute rescues.

The whole film is a race against time, enclosing mini-races. Nolan plays on fears of being crushed, swallowed by darkness, blasted to bits, and shot out of the sky. How many ways can you drown–in a sinking ship, under a flaming oil slick, inside a Spitfire cockpit? The appeals are elemental and irresistible; a child of five could understand the dangers here. This catalogue of stark situations takes us straight back to silent cinema, to cliffhangers, Griffith rescues, and Lang’s dungeons filling with water. Nolan points out:

Dunkirk is all about physical process, all about tension in the moment, not backstories. It’s all about ‘Can this guy get across a plank over this hole?’

Those who want films to focus only on higher things, big ideas or subtle emotions, miss the visceral dimension of cinema. It’s led critics to avoid analyzing musicals, cop thrillers, Asian martial arts films, and Eisenstein’s action sequences. (Ritual invocations of The Body notwithstanding.) The Battleship Potemkin, Police Story, The Raid: Redemption, and much other excellent cinema happily passes The Plank Test.

Does this make the film superficial? Nolan explains that even in the absence of characterization, suspense triggers involuntary, universal responses. Consider Tommy trying to run across the plank.

We care about him. We don’t want him to fall down. We care about these people because we’re human beings and we have that basic empathy.

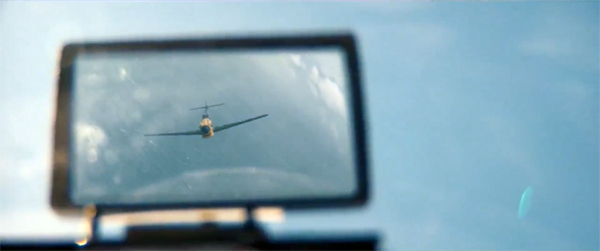

In creating the suspense, Nolan went, as he puts it, “in a more Hitchcock direction.” That entails, for reasons we’ve talked about here and here, playing between restricted and more unrestricted point of view. Not only do we not see the GHQ strategizing, we aren’t taken into the enemy camp. From the start, when gunfire drives Tommy down the Dunkirk streets, the attacks come from offscreen. Only at the very end will a couple of blurry Nazi-shaped figures appear behind the captured pilot Farrier.

In the end, the key for me was reading a lot of firsthand accounts of the people who were there. It became apparent to me that the subjective approach — really putting the audience on the beach with the characters, putting them in the cockpit of the plane, putting them on one of the boats coming across to help — that was going to be the way to tell the story and get across this much bigger picture.

To drive home what it feels like to just barely get by, Nolan ties us tightly to Tommy the foot soldier, Mr. Dawson and his son Peter on their boat, and Farrier the Spitfire pilot, with side visits to Commander Bolton on the Mole. Sometimes he supplies optical POV shots, but more generally he simply confines us to what happens in these men’s ken. The result is both surprise–when the bullets or bombers appear–and suspense, when we cut between Tommy and other soldiers swamped below deck while Gibson struggles to open the hatch and free them.

Even the clicking shut of a cabin latch–or not clicking it shut–generates tension, heightened by the ticking of Zimmer’s score. (At times I thought the pulse in my skull was synched up with the metronomic soundtrack.) The emblem of Nolan’s narrational strategy might be the pitiless shot surmounting today’s entry, showing Tommy flattened while bombs drop one by one behind him, coming inexorably closer to the foreground. Nolan turned superhero films, science-fiction films, and fantasy films into ticking-clock thrillers, and now he does it with a war movie.

The limiting of viewpoint links to some of Nolan’s perennial concern with subjectivity, I think, but it’s also there as a strain within the tradition of war fiction and film. Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front is like a diary, told in first-person present tense but with flashbacks in the past tense. Catch-22 is in long stretches tied to Yossarian’s jumbled memories of flight missions and hospital stays. Terrence Malick’s adaptation of The Thin Red Line, a film Nolan much admires, turns James Jones’ third-person novel into a lyrical fantasia on war as both a violation of nature and an extension of it, with flashbacks and brooding soliloquys. But in Dunkirk Nolan avoids the deeper registers of subjectivity he’s explored before–no memories, no dreams or fantasies, just brute happenings and the stubborn physical demands of earth and rock and water.

The viewpoint range isn’t as narrow as I’ve suggested, though. Nolan broadens his scope by cutting back and forth among the subjective stretches. Again, this is standard operating procedure in the Big Maneuver film. But that crosscutting was never like this.

Time out from battle

Dunkirk, sans credits, runs a little more than 99 minutes and consists of around 99 sequences. It’s very fragmentary. But then, so is a lot of war fiction. All Quiet consists of many fairly short scenes. Evelyn Scott’s vast novel The Wave (1929) surveys the US Civil War through over a hundred vignettes of the home front and the battlefront, involving characters mostly unaware of each other. William March’s Company K (1933) consists of 113 short segments, each bearing the name of one soldier and told in first-person by him (even if he dies in the course of the episode). Unlike what happens in The Wave, the men are mostly known to one another, and some actions are replayed through different viewpoints. A fancier sort of fragmentation goes on in Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (1948), which interrupts its scenes with flashbacks (“The Time Machine”) and sections called “Chorus.”

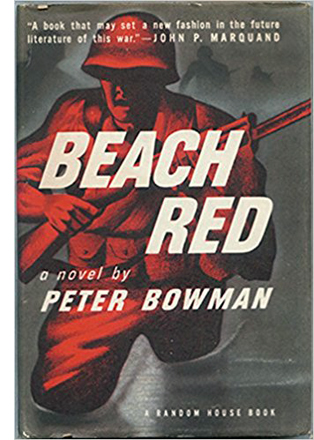

T he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

His novel is in blank verse, in stanzas of varying length but all conforming to a strict pattern. Each line is equal to one second of story time. Each chapter consists of sixty lines, or one minute of story time. And the book has sixty chapters, representing the hour in which the forces take the beachhead. Like Nolan, Bowman wants a deep, visceral subjectivity, and he aims at this through a frankly mechanical layout of his text. The rigid pattern seeks to force the reader to sink into time. Bowman explains:

I have tried to create a mood of inexorable regularity that would correspond to the subtle tyranny of the military timetable. . . . I have attempted to do for the eye what the ticking of a clock accomplishes for the ear. . . the relentless inflexibility of time itself.

The aching inching forward of time is stressed thematically too, which includes reflections like “Would there be armies if clocks had never been invented?” The book ends with the second-person narration (“You”) dying. Soldier Whitney reports: “There is nothing moving but his watch.”

Like Bowman, Nolan is interested in both the psychology of time and the problem of representing it in his artistic medium. I maintained in our book on Nolan that he isn’t only interested in shuffling chronology. I think that he’s particularly keen on exploring what the technique of crosscutting does to story time.

He has explained that he got the idea from Graham Swift’s 1983 novel Waterland.

It opened my eyes to something I found absolutely shocking at the time. It’s structured with a set of parallel timelines and effortlessly tells a story using history–a contemporary story and various timelines that were close together in time (recent past and less recent past), and it actually cross cuts these timelines with such ease that, by the end, he’s literally sort of leaving sentences unfinished and you’re filling in the gaps.

Crosscutting would become a central artistic strategy for Nolan, a way of shaping his other storytelling choices.

Admittedly, what strikes you first about Memento is its flagrant exercise in reversing story order. But that 3-2-1 sequencing is accompanied by a counterpoint, that of chronologically advancing time, 1-2-3 in the present. Backwards-moving sequences are crosscut with forward-moving ones. Likewise, the structure of Following stems from treating phases of a single action as different story strands which can be crosscut. And the shuffling of order in The Prestige comes from intercutting stretches of two characters’ lives in complicated polyphony.

In his last three films, I think that Nolan, intuitively or deliberately, has hit upon an important feature of conventional crosscutting. Nearly all crosscutting in fictional cinema presumes different time spans, or rather different rates of change, in the crosscut lines of story action. We presume that overall the actions are simultaneous, but at a finer level, they proceed at different speeds. Some parts of the action in one line are skipped over, while other actions in another line are prolonged.

This disparity can be seen in some of Griffith’s classic sequences. In The Birth of a Nation, the black soldiers are inches away from breaking into the cabin’s parlor while the Ku Klux Klan is riding to the cabin, but the riders are miles away. If both strands were on the same clock, the Klan would arrive much too late.

Crosscutting allows Griffth to skip over the distance that the Klan covers, so the riders arrive at the cabin “implausibly” fast. Correspondingly, the glimpses we get of the cabin stretch out the action “unrealistically.” To put it technically, we get ellipsis in one line of action, expansion in the other.

Nolan does the same thing in his crosscut sequences. Consider the passage in The Dark Knight when the judge opens the Joker’s fake message. One or two seconds in her timeline are stretched while Gordon’s conversation with Commissioner Loeb runs on a different clock, consuming several seconds. And when Harvey Dent talks with Rachel and is grabbed by Bruce, that action takes even longer.

To speak of different clocks is a bit misleading; we can’t think that the judge turns over the envelope in super-slo-mo. But the idea of different rates of unfolding is useful because it reminds us that crosscutting aims to convey an overall impression of simultaneity. When we look closer, we realize that the action in one story line can be slowed or accelerated while another story line is onscreen.

Nolan’s interest in this quality of crosscutting is literalized in Inception, in which embedded dream actions unfold at different speeds on different levels. In Interstellar, cosmology motivates crosscutting between slow and fast rates of change. In the first planet the astronauts visit, one hour is equal to seven years on earth, so characters literally live at different rates. The pathos of the film depends upon the fact that Cooper returns, barely aged, to his daughter, to find an old woman on her deathbed. But the differential also allows Cooper to appear to her as the ghost that she saw in childhood and, in circular fashion, set him off on his mission.

The war movie as puzzle film

Nolan notes for Interstellar.

For Dunkirk, Nolan found another way to highlight the rate differences secreted within crosscutting. Like Bowman in Beach Red, he lays down crisp time markers. Farrier’s combat sortie lasts one hour; Dawson’s rescue efforts at sea last one day; and events around the breakwater (the Mole) are said to consume one week. The actual evacuation ran longer, but Tommy and his pal aren’t the last to leave.

These three stretches of action could have been presented as separate blocks. We might have been attached first, say, to Dawson and his boat to attain a pitch of excitement during the bombing of the minesweeper. Then we could flash back to Tommy at the start, in a long lead-up to being rescued by Dawson. Finally we could cover the same events yet again by starting with Farrier’s aerial combats and tracing his fate. The film could have concluded with an epilogue showing Tommy and his pal safely on the train.

Interestingly, Kubrick explored this creative option to a limited extent in The Killing, his 1955 adaptation of Lionel White’s Clean Break. As in the novel, one string of scenes sticks with one participant in a racetrack robbery. Then we jump back in time, guided by a voice-over narrator (“About an hour earlier…”) and follow another man leading up to the situation we’ve already seen. Tarantino did the same block-shifting in Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown, and he (rightly) noticed it as a standard literary technique.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action. . . . Flashbacks, as far as I’m concerned, come from a personal perspective. These [in Reservoir Dogs] aren’t, they’re coming from a narrative perspective. They’re going back and forth like chapters.

But Nolan avoided block construction and went for braiding. He splintered his story lines and crosscut them. Events that are mostly taking place at different times are, as it were, laid atop one another and offset. Crosscutting en décalage, we might say.

I’m struck by how bold this is. A more conventional choice would be to confine the action to a fairly brief stretch of time, say two hours, with the rescue fleet arriving at the climax. There might even have been an effort to handle the action as occurring in “real time,” that is, with the duration of the scenes matching their duration in the story. In any event, Nolan could have crosscut his four men–Farrier in the air, Dawson and others at sea, Bolton and Tommy around the Mole–at the points when their activities are roughly simultaneous. If Nolan wanted to include earlier incidents, such as Tommy’s escape from the Germans or his efforts to board the Red Cross ship, those could have been presented as personalized flashbacks. Instead, all that material appears in chronological scenes, but on three distinct time scales.

Nolan set himself enormous problems with this choice. He chose to show the time frames without recourse to an onscreen calendar or clock; after the three initial titles indicating the places and the time spans, we get no more explicit markers. Then Nolan faced the problem of how, on a finer-grained level, to gather these fragments into a whole. He had to create parallels, and, eventually, convergences.

So early in the film, Tommy and Gibson run a stretcher to the departing Red Cross ship.

Cutting makes their urgency flow into that of Mr. Dawson hastening to cast off before the navy requisitions the Moonstone.

Forty-five seconds later Farrier’s team is sent to Dunkirk.

In story time, of course, these aren’t simultaneous at all. Tommy’s attempted escape happens days ahead of Mr. Dawson’s departure, which is hours ahead of Farrier’s mission. But Nolan, aided by Hans Zimmer’s endlessly propulsive score, has given all three primary roles in launching the film’s plot, the start of a time-gapped fugue.

That sort of primacy works at a higher pitch when two life-or-death situations are intercut. Tommy, Alex, and some other soldiers have rashly taken shelter in a fishing trawler, hoping that the tide will carry them away from the beach. But they get pinned inside by target fire. The tide has indeed pulled them out to sea, but the hold is taking on water–at the “same time” (not) that Collins, trapped in the cockpit of his ditched plane, is himself about to drown. The two scenes are intercut.

At the climax, the gestures of rescue are exuberantly crosscut: Dawson hauling on the oily survivors of the blasted minesweeper, the civilians helping the stranded soldiers clamber aboard their boats.

In this passage, Nolan daringly cuts single shots of Dawson’s Moonstone moving as if in sync with the impromptu flotilla, even though he’s some distance off; the crosscutting makes him visually one of the fleet near the Mole.

Crosscutting can also dial up the suspense by delaying the outcome of a line of action. Farrier’s dogfights are pretty much incessant, so cutting away from them to more placid action on the beach or in Dawson’s boat postpones their outcome. Nolan points to another advantage of intercutting the different periods:

You have three different intertwined storylines, and you have them peaking at different moments, so that the idea is that you always feel like you’re about to hit–when you’re hitting the climax of one episode of the story . . . then another one is halfway through and the other one is just beginning. So there’s always a payoff.

Nolan compares this to the “corkscrew” effect of the Shepard Tone in music, which David Julyan used in the drone soundtrack of The Prestige.

At other points, the crosscutting uses one line of action to explain another. While Tommy and Gibson take refuge in the second ship, the Shivering Soldier tells Dawson he refuses to return to Dunkirk because his ship was hit by a torpedo. Soon enough we see a torpedo rip open the ship and plunge Tommy, Gibson, and Alex into the night sea. And soon after that, when they try to clamber into a lifeboat, they’re told by an officer to stay in the water: it’s the Shivering Soldier, pre-PTSD. The contrast between his cool efficiency near the Mole and his spasm of cowardice on the Moonstone is another proof of war’s disastrous impact on warriors.

The lines of action, segregated by crosscutting, intersect eventually. Farrier’s teammate Collins ditches his plane and is rescued by Dawson; later Tommy will get on the Moonstone as well. These are staggered a bit in the film’s unfolding, having the effect of replays. At at least one point, though, I think that all three lines converge. One moment unites Farrier shooting down the German bomber, Dawson steering his ship away from the falling plane, and Tommy, dragged along underwater and hauled to the deck. Shortly the realms of Air and Mole converge when Bolton sees the German plane go down and his men cheer Farrier’s plane as it glides past.

After these moments are briefly pinned together (the script calls it the “confluence”), the time scales diverge again. The epilogue phase of the film resets each strand’s clock. The rescued men arrive at Dorset, and Tommy and Alex board a train at night. Back at the Mole, it’s still daylight and we can see Farrier’s plane burning in the distance. A day or so later in Dorset, the newspaper has published a tribute to George. Now we see Farrier days before, still within his allotted hour of story time, guide the plane down, step out, and set fire to it, as Tommy reads from Churchill’s speech.

Three viewings of the film weren’t enough for me to catch all the alignments, shifts, and echoes, the glimpses of things that take on importance only retrospectively. Early on, a distant shot of Collins’ downed plane briefly shows what turns out to be the Moonstone chugging towards it. On first viewing I was puzzled by Farrier’s view of a sinking private ship; only on the second pass did I realize that it’s the blue trawler that we’ll later see the young soldiers hiding in and fleeing from. And it’s likely, even with many pages of notes, that I’ve mistaken some of the juxtapositions that fly by. (The film averages about 3.3 seconds per shot, and sometimes we jump across story lines in a fusillade of alternations.) Like other puzzle films, the film demands rewatching and scrutiny, and it merits it.

In all, Nolan has taken the conventions of the war picture, its reliance on multiple protagonists, grand maneuvers, and parallel and converging lines of action, and subjected it to the sort of experimentation characteristic of art cinema. (As, in a way, Bowman’s time-grid in Beach Red anticipates the rigor of the Nouveau Roman.) Nolan exploits one feature of crosscutting: that it often runs its strands of action at different rates. He then lets us see how events on different time scales can mirror one another, or harmonize, or split off, or momentarily fuse. As a sort of cinematic tesseract, Dunkirk is an imaginative, engrossing effort to innovate within the bounds of Hollywood’s storytelling tradition.

The juxtapositions aren’t just fancy footwork, I think. In this film, because of the imminence of danger, heroism gets redefined as luck and endurance.

A cynic could call the movie Profiles in Cowardice. Tommy flees German bullets and instead of helping the French hold the barricades, he keeps running. The French boy steals boots and an identity in order to get off the beach sooner. He and Tommy try to slip on board a departing Red Cross ship as stretcher bearers. When that fails, they hide among the pilings. When the ship is hit, they leap into the water, the better to pretend to have been among the survivors and get a new ride. The Shivering Soldier wants to cut and run, and the soldiers who drift beyond the perimeter plan to use the blue trawler to carry them to safety, jumping the evacuation queue. All too often, despite acts of aid and comfort, it’s every man for himself.

At one point Alex claims “Survival’s not fair.” Too right. Mr. Dawson risks his and his son’s life to save a few men, while the lad George, who joined them on impulse and promised to be useful, dies before he can do much, accidentally killed by the Shivering Soldier. The closest the film comes to standard war-movie heroics is Farrier’s cutting down Stukkas. And he doesn’t make it back.

By plunging Tommy and his counterparts into almost unremitting peril, Nolan’s suspense tactics lower the bar for heroism, making us hope that they simply get away, somehow. Trapped on land and sea, you can’t fight dive bombers, U-boats, and marksmen squeezing in from the perimeter. At the end, the boys disembarking at Dorset are reassured that survival was enough. And thanks to Nolan’s crosscutting, individuals at different points in time are shown pulling together to make retreat its own victory.

I wrote nearly all this entry before I got a copy of the published screenplay. Reading Nolan’s conversation with his brother there enabled me to add the quotation about catching lines of action at different points (p. xxii). This conversation also considers the reasons Nolan omitted GHQ scenes (mentioning A Bridge Too Far) and adds comments about Hitchcock, early sound filming (some mistakes here), and The Thin Red Line (“maybe the best film ever made,” xiii). As far as I can tell, the screenplay is fairly close to the finished film until the climactic bombing of the minesweeper; at that point, the onscreen editing doesn’t completely match what’s on the page.

Speaking of climaxes, I should add that even though the film is in Nolan’s sense “all climax,” it also falls quite nicely into Kristin’s four-part structure. I think the midpoint comes when Tommy and his mates head to the blue trawler, starting a typical Development section.

My quotation from Tarantino comes from Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (New York: Applause, 1995), 69-70. The Nolan quotation about Waterland comes from Jeff Goldsmith, “The Architect of Dreams,” Creative Screenwriting (July/ August 2010), 18-26 (available, sort of, here).

On the tendency of war novels to play with time, it’s worth mentioning that Catch-22 may exemplify one weird possibility. The Yossarian plotline slips between past and present very fluidly, with some sentences containing several jumps to and fro. The Milo Minderbinder plot is linear, tracing Milo’s building of his empire in 1-2-3 order. But Milo’s progress appears at different moments in past and present in the Yossarian strand, so some critics have argued that the novel has a deliberately impossible time scheme. See Jan Solomon, “The Structure of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22” (1967) and, for rebuttal, Doug Gaukroger, “Time Structure in Catch-22“ (1970). Even if Catch-22 doesn’t actually do this, it remains a creative option that someone should try. Mr. Nolan?

Is the name of Dawson’s boat, the Moonstone, an homage to Wilkie Collins’ 1868 mystery novel? Collins tells the story through different character viewpoints and skips back and forth in time, using replays that gradually explain what’s going on. Mr. Nolan?

For more on block construction, especially in the work of Tarantino, see this entry. You can find more of our thoughts on Nolan’s work in our book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages (with lots more about crosscutting). See also our blog entries on Inception (here and here), “Superheroes for Sale,” and “Niceties,” and our online article (originally in Film Art) on sound in The Prestige.

Dunkirk (2017).