Archive for August 2017

DUNKIRK Part 1: Straight to the good stuff

Kristin here:

All kinds of spoilers ahead.

The last time I wrote about a Christopher Nolan film on this blog, I was defending the unusual use of protracted exposition to explain Inception’s complicated plot premises. (Critics had complained about the lack of character depth, though I daresay that we knew more about those characters than we do about the ones in Dunkirk.) Concluding that discussion, I said, “I don’t see why we should get annoyed because Inception doesn’t contain rich, fully rounded characters. It’s clearly a puzzle film that takes the usual complicated premises of a heist movie and pushes them to extremes. Accepting the flow of nearly continuous exposition may remove some of the frustrations viewers face. After all, there’s no rule against it.”

Art occasionally does have rules, often imposed from without by government dictate or patronage preference. Artists can impose rules on themselves to guide their creativity, or groups of artists can agree upon rules that define specific types of artworks, like sonnets or sonata-allegro form. But mostly it has norms and conventions–rules of thumb rather than strict rules–and originality consists of playing with them in interesting ways. Now Nolan gives us a film that has even less character psychology and backstory than in Inception, but it also avoids that film’s great lashings of exposition.

Most reviewers seem to have understood that depth of character and explicit elaboration of complex premises are not what Nolan was going for:

If the result holds individual characters at a bit of a remove, then, it isn’t by accident. The enormity of the potential destruction, and the scale of the evacuation and defensive military action, would likely be hampered if the film indulged in too much narrative buildup or character backstory. (Alissa Wilkinson)

In a compact 105 minutes, he takes what was in reality a nine-day effort and brings it all into focus, even without dwelling on a lot of character exposition or development. This is not a typical war picture in which we get much backstory of the men fighting it. […] Told from different perspectives on land, sea, and air, we barely even know the names of the key characters. (Pete Hammond)

The latter point is certainly true. Most of the characters’ names are only given in the credits (and possibly in some of the notoriously inaudible passages of dialogue).

A few reviewers complained, however. Deborah Ross, a critic who in the old days might have been characterized as “dyspeptic,” shunts off her own response onto her readers.

But mostly you must understand that Nolan wants us to come at events as they happened, which means this isn’t about individual heroism, or any kind of character development. (No one carries a letter from a beloved in their inside pocket, for example.) It is brave, and even admirable, but if you are fond of an emotional core? Then you will sorely feel the lack of it. (Deborah Ross)

The readers might or might not find this a failing. Clearly Ross did, but I don’t think this reaction is typical. Surely suspense, empathy, pity, admiration, and ultimately bittersweet relief and pleasure are evoked by this film. My friends and colleagues who have seen the film describe audiences remaining dead silent, a rare thing these days, riveted to the screen throughout. That was certainly true in the two viewings I have had so far.

Let’s assume that Dunkirk does arouse emotions in most viewers, though using an approach that departs from that of conventional war films. Let’s also assume that the story being told is fairly simple, though made elaborate by the ingenious intercutting among the three time frames. David will discuss those two traits in Part 2 of our discussion.

On a need-to-know basis

How Nolan does Nolan convey what little exposition he gives us? Of course, his subject is a famous historical instance of triumph in the face of overwhelming adversity. The Dunkirk evacuation is familiar to most British citizens, and educated Americans and others will have at least a bare-bones notion of the event. Still, he obviously needs to get across points that are salient to this particular film’s treatment of this huge, relatively length operation. (The Dunkirk evacuation took place from May 26 to June 4, 1940.)

Rather than the frequent explanations Nolan used in Inception, here he drops in little pellets of premises at intervals that get broader as the film progresses.

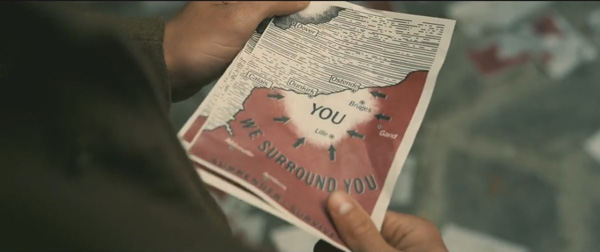

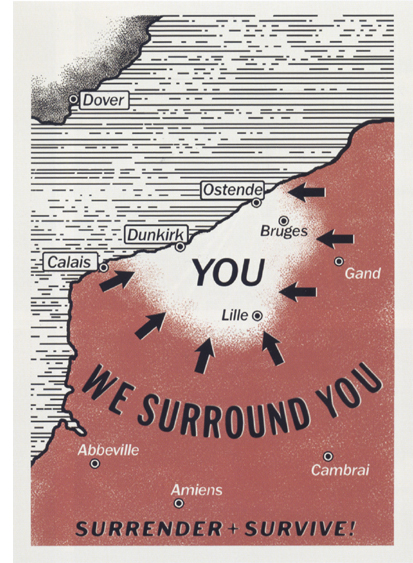

To start with, Nolan gives us the basics of the initial situation–which remains the basic situation until very near the end–all at once with written texts. A title gives the most salient facts about the 300,000 troops trapped by the Germans, and in the first scene the information is supplied with admirable economy by the German fliers dropped on a small band of British soldiers. The one we see in close-up (above) provides the only map we’ll ever see. (At right, the flyer as designed for the film, from James’ Mottram’s The Making of Dunkirk.) Indeed, this is among the few bits of written information we ever get during the main plot; in addition there are the three early titles establishing the geographical areas and their plotlines, the names of the ships and boats, and the chalked records of fuel levels on the control board of the main pilot, Farrier (Tom Hardy). In a conventional war movie, we might expect explanatory maps pored over by officers or letters from home read out by idle soldiers. Writing returns in the epilogue, with the newspapers that report the triumphant retreat, show us George’s obituary, and provide Churchill’s speech, as read by Tommy.

the names of the ships and boats, and the chalked records of fuel levels on the control board of the main pilot, Farrier (Tom Hardy). In a conventional war movie, we might expect explanatory maps pored over by officers or letters from home read out by idle soldiers. Writing returns in the epilogue, with the newspapers that report the triumphant retreat, show us George’s obituary, and provide Churchill’s speech, as read by Tommy.

Apart from telling us that the troops are surrounded, the white area of the map on the flier explains that the trapped men are on beaches extending from Ostende in Belgium to nearly Calais in France. This lets us know that the entirety of the 300,000 trapped men are not at Dunkirk itself and that we should expect to see only a part of that group. At the bottom of the map and difficult to read (this is why we see it in IMAX) is another message, “Surrender + Survive.” This will be a tale of survival without surrender–apart from Farrier’s heroic self-sacrifice at the end. He surrenders and presumably is killed, while most of the others do survive.

After this we get mere scraps for a significant stretch of time. The notion of an organized, prioritized evacuation is demonstrated rather than explained. There is the soldier at the end of a queue who snarls to Tommy that it’s only for Grenadiers. We see desperate French soldiers turned away from the Mole, where a hospital ship waits to take away the British wounded and those assisting them. We learn all this quickly, barely noticing that we’re receiving exposition, and this plotline can go on for a while with little further information.

The setup of Mr Dawson (Mark Rylance), Peter (Tom Glynn-Carney), and George (Barry Keoghan) is sketchy indeed. We learn that the small private boats are being requisitioned for the rescue effort. Dawson is characterized by his neat three-piece wool suit (he discards the jacket for a sweater) and not much else. The brief scene ends with a shot of stacks of life-preservers waiting to be loaded aboard the Moonstone, perhaps hinting at Dawson’s ambition to rescue a considerable number of men despite the apparent small size of his boat. We do not learn where the Moonstone takes off from, though near the end it’s revealed to be Weymouth, a town quite far west from Dunkirk along the southern coast of England.

A cut to the Spitfires in the sky establishes the third timeline of one hour, and the brief scene mainly serves to allow a voice on the radio to set up the idea of limited fuel, with only 45 minutes at Dunkirk possible: “Save enough to get back!” Another brief scene returns to the beach and we see Tommy (Fionn Whitehead) and his friend Gibson (Aneurin Barnard; the name is given only in the credits, and, not being French, is probably the name on the dog-tags he has stolen) trying to pass themselves off as stretcher-bearers in order to get onto the hospital ship, thus trying to evade the prioritized evacuation system set up earlier.

We return to Dawson loading his boat. He looks anxiously at a group of Royal Navy officers and sailors further along the pier. The officers are assigning small groups of sailors to each of the rescue boats, and Dawson obviously is hurrying to cast off before they can reach his boat. (The three Spitfires pass over the Moonstone at this point, providing the first, tangential link between two of the stories.) Dawson says, “I’m the captain!” further implying that he doesn’t want the sailors aboard his boat. He departs, leaving the puzzled-looking officers and sailors looking after him. We never find out why Dawson is so averse to having a few official crew members abroad, and it isn’t necessary to the plot.

After more crosscutting among the plotlines, a Rear Admiral (Matthew Marsh) shows up to talk with Commander Bolton (Kenneth Branagh) and Colonel Winnant (James D’Arcy). They deliver as big a dose of exposition as we get in the course of the film: the German tanks have stopped, Britain needs to get its army back for future battles, the English coast is a remarkably short distance away, Churchill wants to have at least 30-45,000 men out of the roughly 300,000 trapped on the beach rescued, and the sea at Dunkirk is too shallow for any but small boats.

There is no point in picking out all the moments that provide us with information in the course of the film, especially give that the crosscutting is so insistent that most scenes are split up. Nolan takes advantage, however, of having three threads of action running simultaneously. This allows him to explain something through the action of one thread and have that knowledge carry over into one or both of the others. Most notably, there is the scene where Dawson and Peter rescue the Shivering Sailor (Cillian Murphy) from a nearly sunken ship (top). George asks him, “You want to come below? Much warmer.” the Sailor refuses, terrified, and Dawson tells George, “Leave him be, George. He feels safer on deck. You’d be, too, if you had been bombed.”

Immediately before this scene we had witnessed the hospital ship hit, with men jumping from the deck into the sea. There had been no attention paid to those, if any, below deck. Immediately after the scene of Dawson mentioning feeling safe on deck, however, there begins the extended action of Tommy and his French friend being ferried to another large ship where a nurse sends the men below to get tea and jam sandwiches. The door is locked behind them, and Alex (Harry Styles) asks Tommy where his friend went. Tommy replies, “Looking for a quick way out. In case we go down.”

That ship does go down, with the men and nurses trapped underwater in the locked room until Gibson opens the door and lets at least some, including Tommy, escape. The notion of being trapped below deck becomes a major part of subsequent scenes, as Gibson finally drowns when he cannot make it out of the swamped derelict ship in which a group of the men try to put to sea. At one point the attacks cause such chaos that men in the sea are climbing onto a sinking ship’s top deck while at the same time men on lower decks are jumping into the water.

Partly because of the scrambled time-scheme, some exposition ends up being given remarkably late in the action. Well into the film the second Spitfire pilot, Collins (Jack Lowden), is hit and decides not to bail out but to stay with his plane and ditch it in the water. Shortly after this we return to the point where the three Spitfires had originally flown over Dawson’s boat, witnessed by Dawson, Peter, and George. Dawson identifies them as Spitfires and enthuses over them, saying they have Rolls Royce engines. We have seen several scenes with the Spitfires by the point at which they are identified for us. Not that we absolutely need this information, but it invokes the great affection and admiration felt for the Spitfire in Britain and in general helps motivate Farrier’s feats later in the film. The identification also adds a poignancy to Farrier’s defiant immolation of his plane at the end.

More significantly, near the end of the evacuation portion of the film, Collins asks Peter how his father knew how to sail a boat to evade fire from an airplane. Peter replies, “My brother. He flew Hurricanes. Died third week into the war.” (Hurricanes were the other main type of British fighter plane used during World War II.) Almost any other film would reveal Dawson’s loss of his pilot son soon after he is introduced, to motivate his decision to risk going to save other young man and his zealousness in saving as many as he can. Nolan withholds this until nearly the last time we see Dawson. Even if we didn’t learn this scrap of backstory, we would admire Dawson’s willingness to undertake the rescue mission, and we would accept it as due to the legendary British pluck that underlies the whole story.

If we did learn of the death of Dawson’s son early on, we would be likely to view his actions and statements quite differently through the rest of the film and to focus more sympathy on him. This is not, however, a psychological study in heroism. We do not need to know much about these characters. We are inclined to sympathize with people in trouble, especially ones we know are on the right side in a conflict. The crosscutting, the music, the choice of a small number of point-of-view figures to personalize the actions of a much larger group–all these techniques suffice to keep us absorbed.

Often while helping publicize their films, actors describe elaborate backstories they devised as aids for portraying characters, even though none of the information in those backstories would ever be used in the film. Not so with Dunkirk, at least according to Rylance, who describes the simple assumptions he had about Dawson:

Chris is very particular and very much in control of everything as a director, but he didn’t micromanage any of the scenes. He really much responded to how we played the dialogue he had written. The interesting thing about this film is that it doesn’t have 20 minutes of exposition and back story.

What we do know about Mr. Dawson is that he has a wooden motor boat, which I assume had never been across the Channel before. It was for going out with his family in the Bay of Weymouth, which is a town in southwest coast of England, and maybe going along the beautiful coast. It is a pleasure boat that was built in the 1930s and was therefore relatively new at the time. He has a son, who has a friend who hops on the boat.

There is almost nothing here that we can’t learn from what we see on the screen, and even if one is not familiar with Weymouth, the scenes set there were actually filmed on location to give us a quick impression of the place.

In effect, what Nolan has done is to start his film roughly in the middle of a conventional film story, skipping the Setup (exposition) and Complicating Action portions and starting with what would ordinarily be the Development (obstacles) part of the film and its Climax. Then he provides us with snippets of information to get us up to speed without interfering too much with the suspense.

Finally, we don’t need much information to know why and how such people did what they did, because we know it happened.

The color of suspense

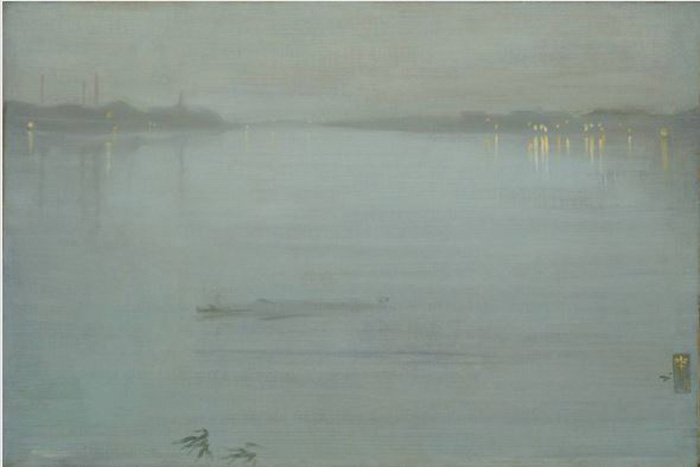

The first short trailer for Dunkirk, called an “Announcement” rather than a “teaser” on Youtube, was posted there nearly a year ago, on August 4, 2016. There were a lot of titles naming Nolan’s previous films, with only six shots, some of which didn’t make it into the final film. The one above, for example, though I’m not sure about some of the others. It’s a pity that one didn’t make the final cut, but my point is that immediately upon seeing that tiny trailer 1) I really wanted to see Dunkirk and 2) I was immediately reminded of James McNeill Whistler’s series of paintings collectively called Nocturnes.

This is rather odd, since the Nocturnes obviously depict night scenes, and relatively little of Dunkirk takes place at night. Whistler’s paintings, however, depict a sort of dusk or night lit up by the glow of London. (They mostly show the Chelsea-Battersea region of the Thames.) They are striking for the wash of nearly monochromatic color with shadowy shapes of buildings or ships or distant shorelines, with a barely distinguishable horizon line, as in “Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremone Lights” (1872)

and “Nocturne: The Solent” (1866).

I’m not implying that Nolan or cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema was influenced by Whistler. I have no idea whether they’re familiar with the artist’s work. I’m just suggesting that they are using a similar technique. Nolan never tries for the level of abstraction present in Whistler’s Nocturnes, since he has a story to tell, and an epic one, crowded with people and vehicles and incidents. Still, through much of the film he uses an unusually restricted range of colors, mostly shades of brown and tan, gray, blue-gray, and black. There is usually something in the foreground, but the action is placed against backdrops that emphasize this same sort of hazy composition where sea, sky, and land come close to blending. Although the land is termed “The Mole” in the first expository title, the first plot thread introduced is essentially the beach and its surroundings, and so earth, air, and sea are emphasized by the very fact that they are not as sharply differentiated as one might expect in a conventional film.

To be sure, the first scene is crisply focused and brightly lit, so that we can get a good sense of the geography of the beach and sea and the vulnerability of the men crowded on it.

Soon, however, the sunlight disappears, and we are left with a much hazier background of more muted colors, with a gray sky and ocean, as Tommy and Gibson begin their attempt to carry a stretcher aboard the hospital ship.

The Mole itself creates a stark shape, but the ships and smoking buildings in the distance could come straight out of a Whistler canvas.

The effect is enhanced by drifting smoke or, in a another scene, a light fog.

The shots of the planes occasionally show some blue sky or sea, as do a few of the shots of the Moonstone, as in this one with dark blue water forming a sharp horizon.

On the whole, however, the sea shots show a very muted palette, as in the image at the top of this entry.

In contrast, the harbor at Weymouth from which the Moonstone departs creates a much busier composition, with many crisp verticals and highlights of color which, if not bright, are at least cheerier than the hues on the Dunkirk beach.

The point of this restraint in the use of color is clearly in part to capture the realism of the weather. It also, however, enhances the oppression of the men’s situation as they wait for help in a maddening combination of tedium and terror.

The film’s few bits of bright color are mostly red, and they are mostly associated with rescue–successful or not. Early on there are the large scarlet crosses on the rescue ship that is abruptly bombed and sunk.

Later, Tommy and his comrades are served red jam sandwiches aboard another ship that is torpedoed and from which they barely escape.

The successful rescues, however, come from the fleet of small private boats, with their flags providing flashes of color, modest within the huge frame, as befits the little boats they adorn.

These flags are Red Ensigns, with a Union Jack in the upper corner of a red rectangle; they are used by civilian boats in the UK.

Dawson’s ship, oddly enough, flies a Blue Ensign (above) rather than a red one. Is this just an attempt to hold back the red motif until we see the other small boats nearer the Dunkirk coast? Or are we to read a scrap of backstory for Dawson in this particular flag? The Blue Ensign has a confused history, having been used through much of British history for a variety of purposes, and only someone with specialist knowledge would be able to interpret it. Most obviously it might simply identify Dawson as a member of the Royal Dorset Yacht Club, one of a number of such clubs with the right to use that flag. Alternatively, it might mark the Moonstone as being owned by a retired Navy man or a member of the Royal Navy Reserve. In any case, to the degree that anyone notices and interprets Dawson’s Blue Ensign, it motivates his skill as a seaman and his ability to rescue enough men to make an officer back in Weymouth exclaim in astonishment, “How many you got here?” as they disembark.

The use of variants of the Union Jack to create these little flashes of red hardly constitutes a riot of color, but it does effectively mark out the boats (one of which has a set of red sails) and to visually echo the cheers of the waiting soldiers as their saviors approach.

Incidentally, the Spitfires have orange-red dots at the centers of their surprisingly target-like decorations, creating a variant of the motif (below). The penultimate shot in the film lingers on Farrier’s Spitfire, which he destroys to prevent its falling into German hands, blazing away as the red of rescue grows bigger and brighter and comes to signify the defiance we hear as Tommy finishes reading Churchill’s speech–a speech that mentions sea, air, and land.

Whistler’s “Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremone Lights” is in the Tate, accession number N03420; “Nocturne: The Solent,” is in the Gilcrease Museum, accession number 0176.1185

You can find more of our thoughts on Nolan’s work in our book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages, in our blog entry “Niceties,” and in our online article (originally in Film Art) on sound in The Prestige.