Archive for October 2017

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Post-partum downs and ups

The Human Comedy (1943).

DB here:

Some authors think that once their book is published they can lean back and wait to hear what people think. On the contrary. Sometimes the care and maintenance of your book continues well after the publication date.

For one book I did, the university press had promised to run an ad in Film Quarterly. When no ad appeared, I was told that since the press itself published Film Quarterly, it had to yield space to publishers who actually paid for their ads. On a more memorable occasion, a catalog listing the season’s titles from Harvard ran a picture of me that showed a different guy. Someone had chosen a shot of the distinguished literary critic and political commentator David Bromwich, who’s regrettably better-looking than me.

Most recently, I just learned that Harvard has put my On the History of Film Style out of print. (Snif.) It was a favorite of mine, and over its twenty years it sold decently, over 10,000 copies. But with all those stills it’s an expensive book to reprint, and so the rights have reverted to me. I hope to revive it somehow, perhaps in print as I did with the Harvard orphan The Cinema of Eisenstein, kindly picked up by Bill Germano, then of Routledge. Or I might go the digital route, creating a straight-up pdf of the old version (as happened with Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment), or something fancier, as with the 2.0 edition of Planet Hong Kong (another book Harvard discharged). Today we Dr. Frankenstein authors have a lot of ways to jolt our creatures back to life.

Most recently, I just learned that Harvard has put my On the History of Film Style out of print. (Snif.) It was a favorite of mine, and over its twenty years it sold decently, over 10,000 copies. But with all those stills it’s an expensive book to reprint, and so the rights have reverted to me. I hope to revive it somehow, perhaps in print as I did with the Harvard orphan The Cinema of Eisenstein, kindly picked up by Bill Germano, then of Routledge. Or I might go the digital route, creating a straight-up pdf of the old version (as happened with Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment), or something fancier, as with the 2.0 edition of Planet Hong Kong (another book Harvard discharged). Today we Dr. Frankenstein authors have a lot of ways to jolt our creatures back to life.

There are still used copies of On the History…. on Amazon. This is a Good Thing. Still, the Age of Amazon creates other post-partum problems.

In conversation and email, I’ve been hearing from people about the Big Cahuna’s treatment of my 40s book. At first Amazon promised to ship copies on the publication date, 2 October (although the University of Chicago Press was shipping copies a week or so before). Nothing happened. Then Amazon third-party sellers offered copies pronto at $30, $10 less than cover price. Then Amazon joined the fray by offering copies at $32 with Prime membership, thereby undercutting those outlets charging for shipping. This is dynamic pricing in fast motion. Such fluctuating pricing by Leviathan’s algorithms must drive publishers crazy.

Still with me? Those other outlets sold their copies, leaving Amazon the sole vendor. The price went back up to list, $40. For the last ten days Amazon has claimed that the book is out of stock, with no shipping date yet determined. This morning, the algorithm declared that one copy was available, but more were coming soon. Sure enough, as I sat down to write this entry, Amazon was offering copies, with Prime, at $40.

But I just checked again and–Amazon has just reverted to competing with third-party vendors offering it between $26 $31.71 and $41 $45.79. Who’s the nervy profiteer who charges a dollar $5.79 above list? (Prices revised as of 13 October.)

So hurry! These prices won’t last long! (Of that you can be sure.) If you want stability and fast delivery at the original price, you can go to the University of Chicago site.

I know, I know: First-world problems. So let me end by thanking two critics for their generous reviews, newly hatched. Both understood that I was aiming for a broad scope, trying to stress the breadth of storytelling innovation of the period. Given that emphasis, in Film Comment, Nick Pinkerton understood why I inserted interludes on particular films and filmmakers:

Tony Rayns in Sight & Sound rightly saw the book as trying to do something different from auteur studies, but he too got that the Interludes tried to right the balance by going deep on particular classics and directors.

Tony is right about the book’s giving Menzies short shrift, but I’ve devoted some attention to him elsewhere (here and here). Blogging has been a good way to offload material that I decided to keep out of the book. Likewise, maintaining this site allows me to post clips of 40s films I talk about. Feel free to check them out.

I thank these reviewers, and any of this blog’s readers who have bought the book.

Next up, and for free: One last big job.

Neither Nick’s nor Tony’s review is online, as far as I know.

As usual, I owe massive thanks to Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. They and their colleagues have made the production, and post-production, of this book exceptionally un-traumatic.

For more background on my Forties research, see the category 1940s Hollywood. I commemorate the day I shipped out the damn thing here. No, I don’t blog in my pajamas, but I do sleep in my clothes.

P.S. 12 October 2017: Alert reader Geoff Gardner points out that today the not-so-failing New York Times published Douglas Preston’s explanation of how Amazon’s new algorithm pushes gray-market “new” books. Thanks to Geoff! Check out his Film Alert 101 blog.

The Curse of the Cat People (1944).

THE LOST WORLD refound, piece by piece

Kristin here:

Like just about all kids, I was fascinated by dinosaurs for a while. That’s probably why my mother bought a copy of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 fantasy-adventure novel, The Lost World, at a yard sale and gave it to me to read while I was sick in bed. I must have been about nine. It was a battered photoplay edition, complete with photos of scenes from the 1925 movie. I read other Victorian-Edwardian fantasy-adventure books, mostly Verne and Haggard, at around the same time. I suppose they prepared me for reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings at age 15 and developing a life-long attachment to them. This doesn’t mean that I consider The Lost World a masterpiece, but having come to it so young, I retain a fondness for it. I was interested to find out what the new Flicker Alley release of a new restoration of the film is like.

Doyle’s novel deals with a scholar and explorer, Professor Challenger, who has recently visited a remote site in South America and is ridiculed by all for his claims that dinosaurs survive on an inaccessible plateau there. The hero, Edward Malone, a lovelorn reporter courting a woman who insists she wants a daring, heroic husband, enlists on an expedition to test Challenger’s stories. So does a skeptical rival of Challenger’s, Professor Summerlee, and a hunter-adventurer, Sir John Roxton, who wants to add a stuffed dinosaur to his other trophies. Many adventures follow, including vengeful Spanish guides marooning the expedition atop the plateau, where they encounter dinosaurs, ape-men, and Indians. The team escapes and manages to take a pterodactyl back to London. Challenger’s reputation is restored.

Following on the novel, I saw the 1960 Irwin Allen version of The Lost World. At the age of perhaps ten or eleven I enjoyed it, though I did recognize that Jill St. John’s character was a total and unnecessary fabrication and the “dinosaurs” were lizards with prostheses.

The 1925 version

Naturally when I was a grad student in film studies, I took my first opportunity to see the 1925 version. It was produced by the important studio and distributor First National Pictures three years before it was absorbed by the upstart Warner Bros. In those days the only version available was a 50-minute abridgement made by Kodascope, and it was not, to say the least, impressive.

I cannot say that I paid much attention to the subsequent restorations: the 1998 George Eastman House version, which, while still incomplete, was a distinct improvement, and the the 2000 David Shepard version, which was basically the same but with digital improvements to sound and image.

The 2016 restoration by Serge Bromberg’s Lobster Films as presented now on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley, has added considerable footage. This extends the film to 103 minutes, close to its original running time. The main thing missing is a scene of cannibals attacking the expedition members as they travel upriver to the controversial plateau, as well as a few other brief moments.

As an adaptation, it’s a distinct improvement on the 1960 version. After all, the novel was only 13 years old when it was made. Doyle was still alive; he would not publish his final Sherlock Holmes story until 1927 and his final works of fiction until 1929. Conventions and tastes in popular fiction, whether filmic or literary, had not changed nearly as much as they had by Irwin Allen’s day.

The main casting was impeccable, with Wallace Beery the perfect choice for the powerful, pugnacious Challenger (above) and Lewis Stone for the epitome of British stalwart rectitude. The film even managed to do a good job of concocting a love interest by introducing Paula White (Bessie Love), the daughter of the original discoverer of the lost-in-time plateau and eager to participate in an expedition to rescue her marooned father. Then it gave her little to do. Bessie Love just has to look terrified at intervals, in a series of close-ups surrounded by an iris and with a blank background–clearly shot later with someone telling Love just to glance in all directions and register fear. These moments add up to something a realization of a Kuleshov experiment.

Her presence does, however, allow Stone to give perhaps the most subtle and sympathetic performance in the film. He’s in love with White but nobly gives her up to Malone. As Malone, Lloyd Hughes manages to look suitably handsome and impetuous. Arthur Hoyt, older brother of director Harry O. Hoyt), plays Professor Summerlee. His many “little man” roles later included the hotel owner in It Happened One Night, and he was one of Preston Sturges’ regular actors. (“Looking perpetually befuddled was Hoyt’s stock-in-trade,” as I. S. Mowis puts it in his IMDb biography of Hoyt.) Unfortunately the film exaggerates Summerlee’s somewhat amusing traits, thereby making him a strictly comic character. (One wonders how Claude Rains, so very dissimilar from Beery, could be chosen for the same role in the 1960 version. Casting against type, presumably.)

By the way, although the film seems basically to be set in the Edwardian era of the novel’s original publication, the introduction to the final London portion of the story shows Piccadilly Circus at night, including a movie palace show The Sea Hawk (1924), another First National release that included Wallace Beery and Lloyd Hughes (Malone) its cast.

A little synergy that brings the story up to date.

Puppets and people

The main attraction of the film, of course, is its technology. Some of it was quite innovative. It is thought to be the first time when the special effects of a feature film were largely accomplished through puppet animation.

There had been earlier puppet films, including Ladislas Starevich‘s realistic creation of artificial insects apparently acting out conventional melodramas. Accomplished though they were, these did not mix live-action with real actors in the same shots, as do the miniature landscapes with the moving dinosaurs.

In The Lost World, combinations usually involve the actors placed in the lower foreground, observing the dinosaurs from varying distances. Atop this section, for example, in a very skillfully done shot, an allosaurus approaches the campsite of the expedition members. The place where the live-action at the lower right joins the miniature set at the upper left is difficult to discern, and the careful lighting of both areas aids in the illusion.

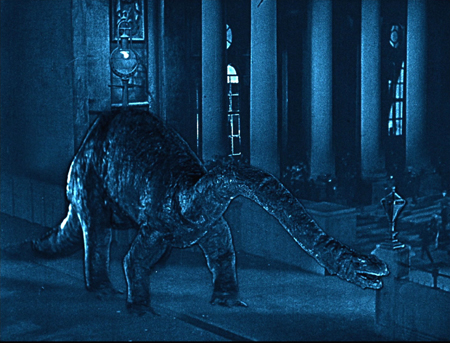

The late scenes of the film, where a brontosaurus escapes into London’s streets and causes panic resorted to a new and complex technology, moving mattes. This device involved using stencils cut for each frame and doubly exposing prints from two negatives. Moving mattes allowed figures filmed separately to be inserted into scenes without the use of superimpositions. The result usually was fairly obvious, betrayed by an evident join line around the added figure. Differences in texture and lighting also caused problems. Still, given the technical limitations of the day, the results are impressive. (The most famous use of moving mattes in this era was probably the reunited couple’s oblivious stroll through traffic in Sunrise.)

The Lost World drew more heavily on stationary mattes, and for the most part, the technology is pretty convincing. The scene of the allosaurus-triceratops-pterodactyl fight (at the top) contains a stationery matte. The lower part of the frame is a river with plants on the banks swaying in the breeze. About a third of the way up the composition, there is a join to the miniature set in which the action was animated. There the plants are completely stationery, but the movement of the real plants in the lower area gives a degree of verisimilitude to the whole scene. The shot of the team confronting the allosaurus at the top of this section also uses this technique.

Digital copies let us pause and figure out some of O’Brien’s secrets. After the allosaurus has dispatched the unfortunate triceratops seen in the image at the top of this entry, a dramatic moment occurs in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it flurry of motion as it suddenly snatches a pterodactyl in mid-flight and kills it. Pausing on the action, we can see that O’Brien used wires to support the allosaurus during its leap, as well as nearly invisible wires along which to slide the pterodactyl. I didn’t notice any other scenes in which O’Brien had to resort to visible props.

And at least the dinosaurs, unlike King Kong, didn’t have fur that ruffles almost continually, betraying the movements of the animators’ fingers in between exposures of the frames. As a result, the animation in The Lost World almost looks more sophisticated than that of Kong.

Moreover, O’Brien’s puppets, constructions of rubber and foam over metal skeletons, included balloons inside that could have air pumped in and out to simulate breathing. It’s a measure of the man’s inspiration that he realized how much this technique would contribute to the lifelike quality of the dinosaurs.

One of the supplements gives another insight. It is listed as “Deleted scenes,” or outtakes, but occasionally O’Brien or perhaps one of his assistants (the footage is too indistinct to tell which) pops into the image for a few frames, incongruously appearing submerged to his waist in a primordial landscape.

Such images give a sense of the considerable scale of the miniature landscapes and the puppets, as well as the labor involved in this novel endeavor.

The new print

This newest restoration, having been cobbled together from many disparate elements, inevitably is variable in its visual quality. Much of it is splendid, as indicated in most of the images reproduced in this entry, especially the one at the top. Others are clearly worn, with light lines, as in the shot above of Challenger and Summerlee watching a brontosaurus pass in the background. Again a matte shot has been used, its joint probably running along the top of the little sandy ridge behind which the men hide.

The rather poignant scene of the dinosaurs fleeing from a volcanic eruption is unfortunately worn as well. Such stretches, however, are in the minority.

The new version also includes tinting and toning based on recently discovered footage, as well as a brief scene combining red and blue colors when Malone throws a torch into the mouth of an allosaurus to drive it away.

The disc comes with a booklet by Bromberg outlining the extensive restoration work on the versions of The Lost World, as well as the disc’s two musical-track options, one by Robert Israel and one by the Alloy Orchestra. Supplements include a commentary track by Nicolas Ciccone and some short films and clips by O’Brien. The Silent Era website offers a detailed rundown on the many video releases of The Lost World. Once more Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are to be congratulated on another contribution to the retrieval of cinema’s history.