Archive for 2017

Grand motel

One Crowded Night (1940).

DB here:

If this blog got into the business of recommending movies to watch on TCM, I’d never get any sleep. TCM, an American treasure, runs so much classic cinema of great value that I can’t keep up.

Today, though, as we’re about to depart for Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I’m pausing to knock out a brief entry urging your attention to a minor release that exemplifies some of the trends I try to track in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. The film is no masterpiece, but it’s better than most of the stuff pumped into our ‘plexes, and it can teach us a lot about continuity and change in the studio years.

A few hours in Autopia

In trying to map out the storytelling options developed in the 1940s, I ran into one trend that looked forward to today’s network narratives. I use that term to pick out films that build their stories around the interaction of several protagonists connected by social ties (love, friendship, work, kinship) or accident. Nashville, Pulp Fiction, and Magnolia are some vivid prototypes. The most common form of network narrative back then was based on the Grand Hotel idea, where a batch of very different characters interact in one place for a short stretch of time.

The form comes into its own in the 1930s, as I’ve indicated in a blog on Grand Hotel (1932). That novel/ play/ film popularized the concept, and MGM ran with it under the banner of the “all-star movie.” It was picked up in other 30s films of interest, like Skyscraper Souls (1932, often run on TCM) and International House (1933). But whereas Grand Hotel was a big A picture, most of its successors were B’s—perhaps because such a plot offered an efficient way to use contract players in a short-term project.

I suspect that’s what happened with One Crowded Night (1940), to play on TCM this Thursday, 22 June (7:30 EST). Dumped in the summer doldrums (back then, summer wasn’t a big moviegoing season), it garnered pretty unfavorable reviews. The big complaints were about the coincidences that get piled on. Wrote Bosley Crowther:

The long arm of coincidences does some powerful stretching for the convenience of film stories, but seldom has it been compelled so such laborious exercise as it is in RKO’s “One Crowded Night,” which opened yesterday at the Rialto. In a manner truly phenomenal, it drags together the assorted characters implicated in a multitude of small plots and dumps them, of all places, in a cheap tourist camp on the edge of the Mojave Desert.

It is pretty far-fetched. The Autopia Court, a speck on the flat, hot expanse, is run by a family whose main breadwinner, Jim, has gone to jail. He’s innocent, framed by Lefty and Mat—who show up by chance at Autopia. Meanwhile, a pregnant Ruth Matson gets off a cross-country bus to recover from heat stroke; she’s on her way to San Diego to meet her husband, a sailor.

Things get complicated fast. A trucker who comes through regularly wants to marry an Autopia waitress with a shady past. One of the thugs makes a play for the naïve waitress who’s fed up with this flea-bitten joint. But she’s worshipped by the gas jockey, who’s no match for the city hood.

The interweaving of lives is very dense. Guess who shows up, recently escaped from prison up north? When two detectives come through guarding an AWOL sailor, imagine who he turns out to be? And what if Doc Joseph, an amiable old fraud peddling a potion that cures everything, turns out to lend a helping hand?

No coincidence, no story. And especially in Grand Hotel plots, when people keep running into each other at just the right moment. Films aren’t about reality; one of the damn things is enough. Films are about giving us experiences, and this B picture seems to me quite satisfying—not least because it shows a relaxed but smooth pace almost completely unknown to modern cinema. It’s no small thing to tell so many stories in 66 minutes.

How work looks

Budget-challenged RKO makes a virtue of its limits. The film has a bleached, suffocating squalor. Dust and glare rise up. The outdoor set makes the motel complex look plausibly cheap. The diner is knotty-pine, and as dingy as you could ask. The countertop yields a solid thump when a plate of comfort food hits, and it’s easy to imagine it being gaumy to the touch. Greasy smoke sizzles up from a grill, blurring a poster advertising the good life and a cola that promises “Keep Cool.” And the shot of the disgruntled fry cook Annie owes nothing to pin-up standards.

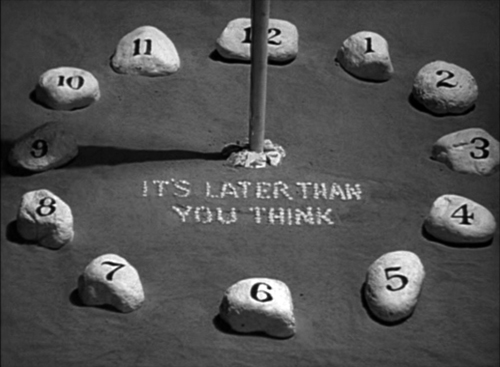

The film has that easy familiarity with the routines of working life celebrated by Otis Ferguson, who praised another film for its “reduction of the rambling facts of living and working to their most immediate denominator, to the shortest and finest line between the two points of a start and a finish.” We watch the Autopia staff briskly feed a busload of people during a ten-minute layover, fix up guest rooms, pour beers, wash dishes, scrub countertops, and pump gas—all the while an enigmatic sundial insists “It’s later than you think.”

With over twenty speaking parts, the film relies on swift, sharp characterizations. It’s lifted above the ordinary by the presence of the splendid Anne Revere, Hollywood’s embodiment of plain-speaking dignity, and the reliable Harry Shannon (aka father to Charles Foster Kane). Beloved blowhard J. M. Kerrigan plays the mountebank. Even a sweat-glistened Gale Storm (older boomers will remember her as TV’s My Little Margie) doesn’t do badly. The presence of so many character actors and bit players gives these people a worn solidity far removed from A-picture glamour. Everybody, young and old, looks fairly ill-used.

Irving Reis joined RKO after a brief but distinguished career in radio, where he created the much-lauded Columbia Workshop. One Crowded Night was his first screen credit at the studio. Renoir gets, deserved, credit for using deep-space compositions to suggest life lived in the background and on the edges of the shot’s main action. Reis, like many unheralded American directors, does the same thing. Network narratives encourage these juxtapositions, as story lines crisscross and characters react accordingly.

Reis went on to do more B pictures, as well as The Big Street (1942) and Hitler’s Children (1943). His later work includes Crack-Up (1946), All My Sons (1948), and Enchantment (1948; discussed hereabouts). He died young, in 1953. One Crowded Night shows him an efficient craftsman; Variety praised him for “development of the story’s many characters and juggling them through the many-sided yarn without confusion.”

The Grand Hotel formula would continue through the 1940s in Club Havana (1945), Breakfast in Hollywood (1946), and other low-end items. It would also yield a few A pictures, like Week-End at the Waldorf (1945, an explicit redo of Grand Hotel), Hotel Berlin (1945), and the hostage thriller Dial 1119 (1950). The format would go on to have a long life, right up to The Second-Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2015).

One Crowded Night, apart from its quiet virtues, served my book as a good example of just how pervasive certain models of storytelling became in the 1940s. Alongside the classic plot patterns of the single protagonist and the dual protagonist (often a romantic couple) other possibilities got explored. Some, like the Grand Hotel model, had been floated in the 30s and got revised in the 40s. Others took off on their own. All left a legacy—let’s call it a tradition—for the filmmakers who followed.

Thanks to TCM and its programmers for making this and thousands of other films available. But why not a version on Warner Archive DVDs? The Spanish DVD is pricy.

My quotations from Bosley Crowther come from “The Screen: At the Rialto,” The New York Times (27 August 1940), 17. The Daily Variety review appeared on 29 July, 1940, 3. Ferguson’s remark, on Joris Ivens’ New Earth, comes from “Guest Artist,” in The Film Criticism of Otis Ferguson, ed. Robert Wilson (Temple University Press, 1971), 126. For more on Ferguson, see my book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

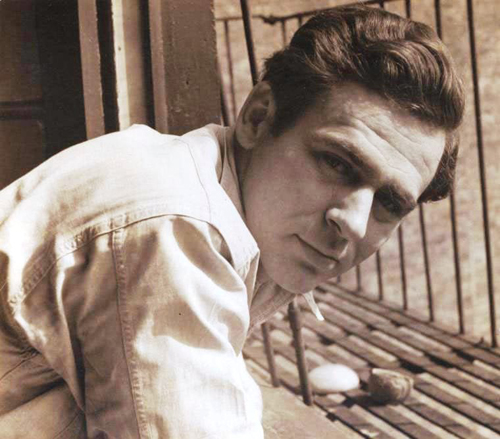

Paul Guilfoyle and Anne Revere in One Crowded Night.

James Agee: Astonishing excellence: A guest post by Charles Maland

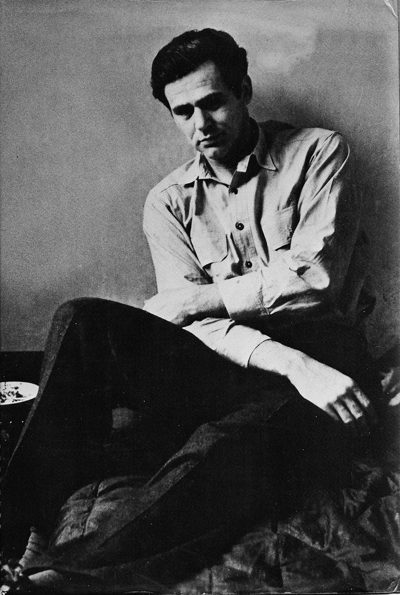

James Agee.

DB here: Charles Maland, a distinguished historian of American film, has just completed editing the definitive collection of James Agee’s film writings. It’s due to be published in July.

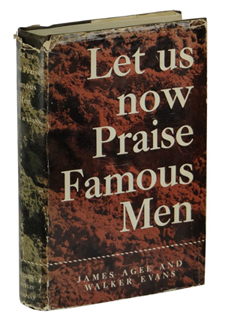

Agee changed American literature with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and he changed film criticism with his reviews for The Nation and Time. After I wrote a 2014 blog entry on his work, I learned of Chuck’s project. Later I decided to turn the entry into a chapter of The Rhapsodes, a study of 1940s American film criticism. Naturally, I turned to Chuck for help. He was magnificently generous, steering me to sources and sharing new material he discovered. In particular, Agee’s unpublished manuscripts contain some powerful arguments and insights. Chuck’s historical introduction to the collection fills in many details of Agee’s relation to popular journalism, to the political and intellectual currents of his time, and to the Hollywood industry.

This book will be one of the most important film publications of 2017. As a warmup, we invited Chuck to write a guest entry on Agee and the process of editing the volume. We’re glad he responded, and we think you will be too.

In the summer of 1927, a precocious seventeen-year-old high school student wrote this to an older friend:

To me, the great thing about the movies is that it’s a brand new field. I don’t see how much more can be done with writing or with the stage. In fact, every kind of recognized “art” has been worked pretty nearly to the limit. Of course great things will undoubtedly be done in all of them, but, possibly excepting music, I don’t see how they can avoid being at least in part imitations. As for the movies, however, their possibilities are infinite—is, insofar as the possibilities of any art CAN be so.

Sixteen years later, British poet W.H. Auden wrote of the “astonishing excellence” of a movie column in The Nation, written by the same person, calling it “the most remarkable regular event in American journalism today.”

Auden was commenting on none other than James Agee (pronounced AY’-jee), a writer that New York Times reviewer A.O. Scott later called “the first great American movie critic.” Acknowledging that Agee didn’t “invent” movie criticism, Scott contends that he did show “what it could be as a form of journalism and a way of talking about the world.”

I concur with Scott about the importance of James Agee’s movie criticism, and for the past several years I’ve been preparing a complete edition of Agee’s movie reviews and criticism. Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, Manuscripts will appear this July from the University of Tennessee Press as Volume Five of The Collected Works of James Agee. Here I’d like to tell you a little more about who James Agee was and how he became a movie reviewer, what problems I encountered and discoveries I made in compiling the volume, and why Agee’s movie writings still deserve our attention.

Who was James Agee, and how did he become a movie reviewer?

James Agee (1909-1955) was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. In his relatively short career he was a feature writer for Fortune magazine; a book reviewer and movie reviewer for Time magazine; a movie columnist for The Nation; a co-screenwriter of, among others, The African Queen and The Night of the Hunter; and author of a volume of poetry, Permit Me Voyage (1934), an expansive social documentary book called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), and two novels, The Morning Watch (1951) and A Death in the Family (1957). The latter was published posthumously and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1958.

The novel also draws on Agee’s autobiography. When Agee was six, his father was killed in a car accident, and the novel explores just such a situation of a young boy, growing up in the Fort Sanders neighborhood of Knoxville, and the way he and his family cope with the father’s death. In real life, following his father’s tragic death, Agee’s mother sent her son to the St. Andrew’s School, a boarding school in Sewanee, Tennessee. After a year at Knoxville High School, Agee transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. There he finished high school and published his first movie review, on F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, which is included in the volume. He then completed his education as an English major at Harvard.

Agee loved movies from childhood. A Death in the Family includes a scene in which father and son walk from their neighborhood to go to the movies in downtown Knoxville, where they see a Charlie Chaplin short and a William S. Hart western. But he didn’t get the opportunity to review movies professionally until the 1940s. His first job as a feature writer for Henry Luce’s Fortune magazine paid the bills.

His book on Alabama sharecropper farmers in the Depression, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, started as an assignment from Fortune, but when Agee discovered that the subject far exceeded the boundaries of a feature article, he took a leave from Fortune to write the book. When it appeared in 1941, Americans were thinking about World War II and it sold only 600 copies, despite some positive reviews. The book’s reputation began to grow during the social turbulence of the 1960s, when it was reprinted and spoke to readers during that era in powerful ways. .

Following that disappointing commercial response, Agee returned to work for Time, Inc., now as a book reviewer for Time. (Volume 3 of the Collected Works, edited by Paul Ashdown, includes all of Agee’s published book reviews and non-film journalism.) While reviewing books, Agee kept alert to openings in the movie section, and he finally got his chance by reviewing The Big Street, starring Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda; the piece appeared in the September 7, 1942, issue of Time.

From then on, he remained on staff at Time as a movie reviewer until November 1948. His reviewing stint was interrupted after he wrote a powerful cover story for Time about the detonation of atomic bombs in Japan. For a few months in late 1945 and early 1946, Henry Luce put him on special assignment to write on social and political topics.

In December 1942, Agee also received an invitation from Peggy Matthews, arts editor of The Nation¸ a left-leaning journal of politics and the arts, to do a regular movie column for that audience. Agee accepted and his first contribution appeared late that month. Agee was writing about movies in two different places until his last Nation column on July 31, 1948. In between, by my best count, he reviewed 561 films in Time and 460 films in The Nation. Of that number Agee discussed 320 titles in both venues.

Agee stopped reviewing because he got the itch to write screenplays. Between 1948 and his death, he sometimes supported himself and his family as a screenwriter. His two most famous credits are on John Huston’s The African Queen (1951) and Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955). (Volume Four of the Collected Works, edited by Jeffrey Couchman, contains the script versions of these two films.) Partly to provide some income after he stopped reviewing but before his screenwriting career gained traction, Agee contracted with Life magazine (another Luce publication) to write extended essays on silent film comedy and John Huston. The resulting pieces, “Comedy’s Greatest Era” and “Undirectable Director,” are familiar to many readers. These pieces, along with some other individual Agee movie essays, like a review of Sunset Boulevard in Sight & Sound, also appear in the collection.

Problems and discoveries

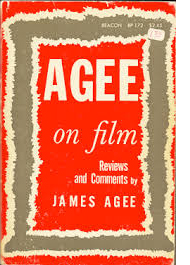

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

Only a small selection of Agee’s Time reviews had appeared in Agee on Film. Because I began with what I thought was a full and accurate bibliography of all of Agee’s Time movie reviews, I thought that compiling them would be an uncomplicated task, too. I was wrong.

When he started reviewing for Time, and especially in his last months there, Agee was only one of several movie reviewers (although he was generally the primary reviewer). For the whole period he worked there, Time did not give bylines to writers. To verify what reviews Agee wrote, I enlisted the services of Bill Hooper, Time’s chief archivist. From him I learned that a copy-desk employee would handwrite in one master copy of each issue the name of the author of every article and review. These issues were then bound quarterly, and they eventually were deposited in the Time archives.

Mr. Hooper generously checked each volume against the bibliography I sent him and also responded to a number of questions that arose from the initial inquiry. The only period he was unable to verify was for the first three months of 1946: the bound volume from that period was missing. Fortunately, though, that was the time when Agee had taken an assignment as a special correspondent for social and political affairs.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

The Agee papers, held principally in the special collections units at the University of Texas and the University of Tennessee, also contained a variety of fascinating information. I learned from financial records that Agee was well paid as a salaried employee of Time and that he was paid modestly at The Nation ($25 a column at first, later—it seems—by the word, which often amounted to less than $25). A few uncashed checks from The Nation in the archives suggest that Agee wasn’t much of a businessman. Other documents contained lists of film screenings that had been set up for Agee; they suggest that he saw a great many films, both in press screenings and regular theatre showings.

Perhaps most interesting for our purposes were a number of previously unpublished manuscripts. They included: 1) four-page typed “Movie Digest,” written in late 1935 or early 1936, containing thumbnail reviews (most with grades—A through F) of films, mostly from 1934 and 1935; 2) a scathing 1938 review of Bardèche and Brassilach’s The History of Motion Pictures that Partisan Review decided not to publish, probably because of how unrelentingly harsh it was; 3) a long letter that Agee wrote upon the request of Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish with suggestions about possible films to include in the Library of Congress film collection; and 4) some notes on movies and reviewing, probably from 1949, for a proposed Museum of Modern Art roundtable discussion of movies. All these manuscripts, including several essays or proposals for essays on René Clair and Sergei Eisenstein—both Agee favorites—are included in the collection.

Agee as movie critic

It’s hard in a short space to make generalizations about Agee’s aesthetic and why he should continue to interest us as a movie reviewer. Yet I would say he’s important for at least five reasons.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

Second, his work is historically significant. He began writing just as the film industries of the United States and its Allies were trying to determine the role of movies during the world war that was raging. In his earliest reviews, Agee tended to celebrate the Allied documentaries (what he called “record” films) to the detriment of fiction movies. He was especially sensitive to a kind of poetic realism that he celebrated in Italian Neorealism (in his review of Shoeshine, for example) and in George Rouquier’s Farrebique.

Third, Agee was a magnificent and witty writer. He could write sustained, insightful essays, like his Time cover stories on Ingrid Bergman and on Laurence Olivier’s Henry V or his famous three-part defense of Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux. But he was also funny, especially when criticizing a film. Early in 1948 Agee got behind in his Nation reviews when he was hospitalized with appendicitis: to catch up he reviewed as many as 25 films in a single column, often in one sentence or two. Here are a few favorites:

On a mystery film starring Claude Rains, Agee wrote: “The Unsuspected is suspected too soon by the audience and too late by most of his fellow actors.” He disposed of an odd cinematic blend of whodunit and romance with this review: “Embraceable You is dispensable entertainment.” A John Wayne vehicle also took it on the chin: “Tycoon. Several tons of dynamite are set off in this movie; none of it under the right people.” He titled his February 14, 1948 column “Midwinter Clearance.” Perhaps my favorite was a Jeanne Crain-Dan Duryea vehicle: “You Were Meant for Me. That’s what you think.”

Fourth, Agee stands out because he had such catholic tastes. Although he was hard to please, he wrote enthusiastically and positively about a wide range of films. Agee praised European classics like Zero for Conduct, Ivan the Terrible (Part One), Day of Wrath, Children of Paradise, and Farrebique; British films like Henry V, Hamlet, Great Expectations, Odd Man Out, and Black Narcissus; a variety of American movies like The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Meet Me in St. Louis, The Big Sleep, The Best Years of Our Lives, Notorious, Monsieur Verdoux, and The Treasure of Sierra Madre; documentary films like Desert Victory, San Pietro, and They Were Expendable; Hollywood B films like Val Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People; the emerging Neorealist films; and dark urban dramas like Double Indemnity that later became known as film noir. Any critic who could write informatively and with enthusiasm about such a broad range of films had to possess a wide-ranging sensibility that welcomed the breadth of artistic possibilities presented by the movies of his era.

I should acknowledge here that some commentators have argued that Agee was not critical enough about really bad films and that he was too equivocal, trying to find something good to say about most of the films he reviewed. I’d respond to these claims in a couple of ways. First, it’s true that Agee was often equivocal in his reviews, but that equivocation often took the form of saying a film could have been more successful if it had done something better, but it didn’t. Another form of Agee equivocation was to say that an otherwise failed film did have some redeeming element (a song, a performance, a stylistically effective moment).

I think the fact that he would sometimes give bad films some positive gesture was partly a function of his love of the movies as an art form. I have to say I’m sympathetic to Agee here. I usually find something redeeming in almost every movie I see, and my wife regularly tells our friends that she’s the true critic in the family—they should ask her, not me, if they should see a film!

Second, I think there’s some difference between Agee’s Nation and Time reviews. He was under tighter editorial oversight at Time, and I think he was under more pressure to avoid completely lambasting a film than he was in his Nation columns. Getting a chance to read all of Agee’s Time and Nation reviews will offer readers an opportunity to think about how he wrote differently about movies for different audiences. The fact remains, however, that of the films and filmmakers he really admired, Agee showered praise on an unusually wide range of different kind of films.

Finally, as David Bordwell has observed, the publication of Agee on Film: Reviews and Essays in 1958 had a strong influence on the growth of film culture in the United States during the 1960s and after. As Bordwell put it,

There’s no knowing how many teenagers and twentysomethings read and reread that fat paperback with its blaring red cover. We wolfed it down without knowing most of the movies Agee discussed. We were held, I think, by the rolling lyricism of the sentences, the pawky humor, and the stylistic finish of certain pieces—the three-part essay on Monsieur Verdoux, the Life piece “Comedy’s Greatest Era,” the John Huston profile “Undirectable Director.” The adolescent fretfulness that put some critics off didn’t give us qualms; after all, we were unashamedly reading Hart Crane, Thomas Wolfe, and Salinger too. Some of us probably wished that we could some day write this way, and this well.

Agee on Film came along at a propitious time: European art film was beginning to flourish and a new generation of critics and reviewers—Sarris, Kauffman, Kael, Schickel, Simon, and later Ebert—engaged with this exciting new film culture. All, at one time or another, acknowledged Agee’s contributions. All, like Agee, published their reviews in book form.

For all these reasons, James Agee’s writings on the movies deserve our continued attention. I hope that by preparing a volume which contains all of Agee’s movie reviews and essays in Time and The Nation, all his other published writings on movies, and a number relevant but previously unpublished essays, I will help enable interested readers to get an accurate and fuller appreciation of Agee’s contributions to our evolving film culture.

Charles Maland is the author of Chaplin and American Culture (Princeton University Press, 1991) and the BFI classics volume on City Lights (2008). We thank him for his willingness to serve as a guest blogger.

Agee’s youthful encomium to film comes from Dwight Macdonald, “Agee & the Movies,” in Dwight Macdonald on Movies (Prentice-Hall, 1969), 3. Auden’s praise of his criticism is in “Agee on Film (Letter to the Editor),” Nation 159, no. 21 (18 November 1943): 628. A. O. Scott’s remarks come from Gerald Peary’s For the Love of the Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism (Bullfrog Films, 2009). The Bordwell quotation is in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2016), 2-3.

Agee’s name was frequently mispronounced. At the end of a 1948 Nation column, Agee apologized for mistakenly calling Amos Vogel “Alex” in a column, then went on to say, “I apologize to Mr. Vogel and to you; and sadly join company with an aunt of mine who used to refer to Sacco and Vanetsi, and with all those who call me Aggie, Ad’ji, Adjee’, Uhjee’, and Eigh’ ggeee’.”

Our next stop: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

P.S. 1 May 2019: For more on Agee, observed from many perspectives, including Chuck Maland’s, see the commentaries at the Criterion Collection.

James Agee, portrait by Helen Levitt.

FilmStruck and Criterion: Now Roku-ready

DB here:

Soon after Kristin posted the seventh installment in our Criterion series, there came the big news. FilmStruck and the Criterion Channel are now available for streaming via Roku. Some details are in this Variety story.

These streaming services had already been available on Apple TV, Chromecast, and other devices, but getting to Roku is a big boost. As of January, Variety says there are 13 million active Roku accounts. Roku capability is built into many smart TVs, and the set-top devices are reasonably low-priced. As a result, and as an early mover in the market, Roku has twice the penetration of its rivals.

Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I hope that subscribers will check out our monthly comments on films both classic and modern. Before or after our discussion, you can watch the films on the Criterion channel. We’ve regarded these short items as extensions of our blog, our research, and our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction. We try to make them clear and engaging.

If you subscribe to FilmStruck, you can log in and go straight to all our offerings. A synoptic page is here. Before Kristin’s entry on The Rules of the Game, we put up Jeff on the score of Foreign Correspondent, me on editing in Sanshiro Sugata, Kristin on landscape in two films by Abbas Kiarostami, Kristin on the child’s viewpoint in The Spirit of the Beehive, me on staging in L’Avventura, and Jeff on camera movement in Kieślowski’s Red. Whether or not you have FilmStruck, you can read blogs expanding on four of those entries here.

Coming up: Jeff on La Cérémonie and Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Kristin on The Phantom Carriage and M, and me on Monsieur Verdoux, Brute Force, and Chungking Express.

And of course both FilmStruck and the Criterion channel offer a dizzying array of features, shorts, interviews, and bonus material. If you had told me just a few years ago that such a bounty would be so easily available, I’d have doubted it. Nothing beats seeing films on the big screen, but as a person who grew up with movies on TV (in small, degraded images and sound), I know that they retain some of their power in a lot of circumstances.

A monthly subscription equals the cost of three of Starbuck’s Cinnamon Dolce Lattes (Venti), whatever they are. Surely this is a great bargain. You can keep up with what’s coming along at Criterion’s website.

To those of you who have signed up and have followed our efforts: Thanks! Keep watching!

Thrill me!

Based on a True Story (Polanski, 2017).

DB here:

Three examples, journalists say, and you’ve got a trend. Well, I have more than three, and probably the trend has been evident to you for some time. Still, I want to analyze it a bit more than I’ve seen done elsewhere.

That trend is the high-end thriller movie. This genre, or mega-genre, seems to have been all over Cannes this year.

A great many deals were announced for thrillers starting, shooting, or completed. Coming up is Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, “centering on members of a church who are troubled by the loss of their loved ones.” There’s Sarah Daggar-Nickson’s A Vigilante, with Olivia Wilde as a woman avenging victims of domestic abuse. There’s Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World, about the kidnapping of J. Paul Getty III. There’s Lars von Trier’s serial-killer exercise The House that Jack Built. There’s as well 24 Hours to Live, Escape from Praetoria, Close, In Love and Hate, and Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, featuring Zac Efron as Ted Bundy. Claire Denis, who has made two thrillers, is planning another. Not of all these may see completion, but there’s a trend here.

Then there were the movies actually screened: Based on a True Story (Assayas/ Polanski), Good Time (the Safdie brothers), L’Amant Double (Ozon), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (Lanthimos), The Merciless (Byun), You Were Never Really Here (Ramsay), and Wind River (Sheridan), among others. There was an alien-invasion thriller (Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Before We Vanish), a political thriller (The Summit), and even an “agricultural thriller” (Bloody Milk). The creative writing class assembled in Cantet’s The Workshop is evidently defined through diversity debates, but what is the group collectively writing? A thriller.

Thrillers seldom come up high in any year’s global box-office grosses. Yet they’re a central part of international film culture and the business it’s attached to. Few other genres are as pervasive and prestigious. What’s going on here?

A prestigious mega-genre

Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958).

Thriller has been an ambiguous term throughout the twentieth century. For British readers and writers around World War I, the label covered both detective stories and stories of action and adventure, usually centered on spies and criminal masterminds.

By the mid-1930s the term became even more expansive, coming to include as well stories of crime or impending menace centered on home life (the “domestic thriller”) or a maladjusted loner (the “psychological thriller”). The prototypes were the British novel Before the Fact (1932) and the play Gas Light (aka Gaslight and Angel Street, 1938).

While the detective story organizes its plot around an investigation, and aims to whet the reader’s curiosity about a solution to the puzzle, in the domestic or psychological thriller, suspense outranks curiosity. We’re no longer wondering whodunit; often, we know. We ask: Who will escape, and how will the menace be stopped? Accordingly, unlike the detective story or the tale of the lone adventurer, the thriller might put us in the mind of the miscreant or the potential victim.

In the 1940s, the prototypical film thrillers were directed by Hitchcock. I’ve argued elsewhere that he mapped out several possibilities with Foreign Correspondent and Saboteur (spy thrillers) Rebecca and Suspicion (domestic suspense), and Shadow of a Doubt (domestic suspense plus psychological probing). Today, I suppose core-candidates of this strain of thrillers, on both page and screen, would be The Ghost Writer, Gone Girl, and The Girl on the Train.

In the 1940s, as psychological and domestic thrillers became more common, critics and practitioners started to distinguish detective stories from thrillers. In thinking about suspense, people noticed that the distinctive emotional responses depend on different ranges of knowledge about the narrative factors at play. With the classic detective story, Holmesian or hard-boiled, we’re limited to what the detective and sidekicks know. By contrast, a classic thriller may limit us to the threatened characters or to the perpetrator. If a thriller plot does emphasize the investigation we’re likely to get an alternating attachment to cop and crook, as in M, Silence of the Lambs, and Heat.

Today, I think, most people have reverted to a catchall conception of the thriller, including detective stories in the mix. That’s partly because pure detective plotting, fictional or factual, remains surprisingly popular in books, TV, and podcasts like S-Town. The police procedural, fitted out with cops who have their own problems, is virtually the default for many mysteries. So when Cannes coverage refers to thrillers, investigation tales like Campion’s Top of the Lake are included.

In addition, “impure” detective plotting can exploit thriller values. Films primarily focused on an investigation, but emphasizing suspense and danger, can achieve the ominous tension of thrillers, as Se7en and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo do. More generally, any film involving crime, such as a heist or a political cover-up, could, if it’s structured for suspense and plot twists, be counted as part of the genre.

Yet tales of police detection aren’t currently very central to film, I think. Their role, Jeff Smith suggests, has been somewhat filled by the reporter-as-detective, in Spotlight, Kill the Messenger, and others. Straight-up suspense plots are even more common, as in the classic victim-in-danger plots of The Shallows, Don’t Breathe, and Get Out. Tales of psychological and domestic suspense coalesced as a major trend in Hollywood during the 1940s. It became so important that I devoted a chapter to it in my upcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. (You can get an earlier version of that argument here.)

By referring to “high-tone” thrillers, I simply want to indicate that major directors, writers, and stars have long worked in this broad genre. In the old days we had Lang, Preminger, Siodmak, Minnelli, Cukor, John Sturges, Delmer Daves, Cavalcanti, and many others. Today, as then, there are plenty of mid-range or low-end thrillers (though not as many as there are horror films), but a great many prestigious filmmakers have tried their hand: Soderbergh (Haywire, Side Effects), Scorsese (Cape Fear, Shutter Island), Ridley Scott (Hannibal), Tony Scott (Enemy of the State, Déja vu), Coppola (The Conversation), Bigelow (Blue Steel, Strange Days), Singer (The Usual Suspects), the Coen brothers (Blood Simple, No Country for Old Men et al.), Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense, Split), Nolan (Memento et al.), Lee (Son of Sam, Clockers, Inside Man), Spielberg (Jaws, Minority Report), Lumet (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), Cronenberg (A History of Violence, Eastern Promises), Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown), Kubrick (Eyes Wide Shut), and even Woody Allen (Match Point, Crimes and Misdemeanors). Brian De Palma and David Fincher work almost exclusively in the genre.

And that list is just American. You can add Almodóvar, Assayas, Besson, Denis, Polanski, Figgis, Frears, Mendes, Refn, Villeneuve, Cuarón, Haneke, Cantet, Tarr, Gareth Jones, and a host of Asians like Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho, and Johnnie To. I can’t think of another genre that has attracted more excellent directors. The more high-end talents who tackle the genre, the more attractive it becomes to other filmmakers.

Signing on to a tradition

Creepy (Kurosawa, 2016).

If you’re a writer or a director, and you’re not making a superhero film or a franchise entry, you really have only a few choices nowadays: drama, comedy, thriller. The thriller is a tempting option on several grounds.

For one thing, there’s what Patrick Anderson’s book title announces: The Triumph of the Thriller. Anderson’s book is problematic in some of its historical claims, but there’s no denying the great presence of crime, mystery, and suspense fiction on bestseller lists since the 1970s. Anderson points out that the fat bestsellers of the 1950s, the Michener and Alan Drury sagas, were replaced by bulky crime novels like Gorky Park and Red Dragon. As I write this, nine of the top fifteen books on the Times hardcover-fiction list are either detective stories or suspense stories. A thriller movie has a decent chance to be popular.

This process really started in the Forties. Then there emerged bestselling works laying out the options still dominant today. Erle Stanley Gardner provided the legal mystery before Grisham; Ellery Queen gave us the classic puzzle; Mickey Spillane provided hard-boiled investigation; and Mary Roberts Rinehart, Mignon G. Eberhart, and Daphne du Maurier ruled over the woman-in-peril thriller. Alongside them, there flourished psychological and domestic thrillers—not as hugely popular but strong and critically favored. Much suspense writing was by women, notably Dorothy B. Hughes, Margaret Millar, and Patricia Highsmith, but Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin contributed too.

I’d argue that mystery-mongering won further prestige in the Forties thanks to Hollywood films. Detective movies gained respectability with The Maltese Falcon, Laura, Crossfire, and other films. Well-made items like Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, The Ministry of Fear, The Stranger, The Spiral Staircase, The Window, The Reckless Moment, The Asphalt Jungle, and the work of Hitchcock showed still wider possibilities. Many of these films helped make people think better of the literary genre too. Since then, the suspense thriller has never left Hollywood, with outstanding examples being Hitchcock’s 1950s-1970s films, as well as The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seconds (1966), Wait Until Dark (1967), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Parallax View (1974), Chinatown (1974), and Three Days of the Condor (1975), and onward.

Which is to say there’s an impressive tradition. That’s a second factor pushing current directors to thrillers. It does no harm to have your film compared to the biggest name of all. Google the phrase “this Hitchcockian thriller” and you’ll get over three thousand results. Science fiction and fantasy don’t yet, I think, have quite this level of prestige, though those genres’ premises can be deployed in thriller plotting, as in Source Code, Inception, and Ex Machina.

Since psychological thrillers in particular depend on intricate plotting and moderately complex characters, those elements can infuse the project with a sense of classical gravitas. Side Effects allowed Soderbergh to display a crisp economy that had been kept out of both gonzo projects like Schizopolis and slicker ones like Erin Brockovich.

Ben Hecht noted that mystery stories are ingenious because they have to be. You get points for cleverness in a way other genres don’t permit. Because the thriller is all about misdirection, the filmmaker can explore unusual stratagems of narration that might be out of keeping in other genres. In the Forties, mystery-driven plots encouraged writers to try replay flashbacks that clarified obscure situations. Mildred Pierce is probably the most elaborate example. Up to the present, a thriller lets filmmakers test their skill handling twists and reveals. Since most such films are a kind of game with the viewer, the audience becomes aware of the filmmakers’ skill to an unusual degree.

Thrillers also tend to be stylistic exercises to a greater extent than other genres do. You can display restraint, as Kurosawa Kiyoshi does with his fastidious long-take long shots, or you can go wild., as with De Palma’s split-screens and diopter compositions. Hitchcock was, again, a model with his high-impact montage sequences and florid moments like the retreating shot down the staircase during one murder in Frenzy.

Would any other genre tolerate the showoffish track through a coffeepot’s handle that Fincher throws in our face in Panic Room? It would be distracting in a drama and wouldn’t be goofy enough for a comedy.

Yet in a thriller, the shot not only goes Hitchcock one better but becomes a flamboyant riff in a movie about punishing the rich with a dose of forced confinement. More recently, the German one-take film Victoria exemplifies the look-ma-no-hands treatment of thriller conventions. Would that movie be as buzzworthy if it had been shot and cut in the orthodox way?

Fairly cheap thrills

Non-Stop (Collet-Serra, 2014). Production budget: $50 million. Worldwide gross: $222 million.

The triumph of the movie thriller benefits from an enormous amount of good source material. The Europeans have long recognized the enduring appeal of English and American novels; recall that Visconti turned a James M. Cain novel into Ossessione. After the 40s rise of the thriller, Highsmith became a particular favorite (Clément, Chabrol, Wenders). Ruth Rendell has been mined too, by Chabrol (two times), Ozon, Almodóvar, and Claude Miller. Chabrol, who grew up reading série noire novels, adapted 40s works by Ellery Queen and Charlotte Armstrong, as well as books by Ed McBain and Stanley Ellin. Truffaut tried Woolrich twice and Charles Williams once. Costa-Gavras offered his version of Westlake’s The Ax, while Tavernier and Corneau picked up Jim Thompson. At Cannes, Ozon’s L’Amant double derives from a Joyce Carol Oates thriller the author calls “a prose movie.”

Of course the French have looked closer to home as well, with many versions of Simenon novels by Renoir, Duvivier, Carné, Chabrol (inevitably), Leconte, and others. The trend continues with this year’s Assayas/Polanski adaptation of the French psychological thriller Based on a True Story.

In all such cases, writers and directors get a twofer: a well-crafted plot from a master or mistress of the genre, and praise for having the good taste to disseminate the downmarket genre most favored by intellectuals.

Another advantage of the thriller is economy. There are big-budget thrillers like Inception, Spectre, and the Mission: Impossible franchise. But the thriller can also flourish in the realm of the American mid-budget picture. Recently The Accountant, The Girl on the Train, and The Maze Runner all had budgets under $50 million. Putting aside marketing costs, which are seldom divulged, consider estimated production costs versus worldwide grosses of these top-20 thrillers of the last seven years. The figures come from Box Office Mojo.

Taken 2 $45 million $376 million

Gone Girl $61 million $369 million

Now You See Me $75 million $351 million

Lucy $40 million $463 million

Kingsman: The Secret Service $81 million $414 million

Then there are the low-budget bonanzas.

The Shallows $17 million $119 million

Don’t Breathe $9.9 million $157 million

The Purge: Election Year $10 million $118 million

Split $9 million $276 million

Get Out $4.5 million $241 million

Of course budgets of foreign thrillers are more constrained, and I don’t have figures for typical examples. Still, overseas filmmakers tackling the genre have an advantage over their peers in other genres. Thrillers are exportable to the lucrative American market, twice over.

First, a thriller can be an art-house breakout. Volver, The Lives of Others, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009) all scored over $10 million at the US box office, a very high number for a foreign-language film. Asian titles that get into the market have done reasonably well, and enjoy long lives on video and streaming. The Handmaiden and Train to Busan, both from South Korea, doubled the theatrical take of non-thrillers Toni Erdmann and Julieta, as well as that of American indies like Certain Women and The Hollers. Elsewhere, thrillers comprised two of the three big arthouse hits in the UK during the first four months of this year: The Handmaiden, a con-artist movie in its essence, and Elle, a lacquered woman-in-peril shocker.

Second, a solid import can be remade with prominent actors, as Wages of Fear and The Secret in Their Eyes were. Probably the most high-profile recent example was The Departed, a redo of Hong Kong’s Infernal Affairs. Sometimes the director of the original is allowed to shoot the remake, as happened with The Vanishing, Loft, and Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Even if the remake doesn’t get produced, just the purchase of remake rights is a big plus. I remember one European writer-director telling me that he earned more from selling the remake rights to his breakout film than he did from the original. He was also offered to direct the remake, but he declined, explaining: “If someone else does it, and it’s good, that’s good for the original. If it’s bad, people will praise the original as better.” And by making a specialty hit, the screenwriter or director gets on the Hollywood radar. If you can direct an effective thriller, American opportunities can open up, as Asian directors have discovered.

Thrillers attract performers. Actors want to do offbeat things, and between their big-paycheck parts they may find the conflicted, often duplicitous characters of psychological thrillers challenging roles. For Side Effects Soderbergh rounded up name performers Jude Law, Rooney Mara, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Channing Tatum. The Coens are skillful at working with stars like Brad Pitt (Burn after Reading). The rise of the thriller has given actors good Academy Award chances too. Here are some I noticed:

Jane Fonda (Klute), Jodie Foster (Silence of the Lambs), Frances McDormand (Fargo), Natalie Portman (Black Swan), Brie Larson (Room), Anjelica Huston (Prizzi’s Honor), Kim Basinger (L.A. Confidential), Rachel Weisz (The Constant Gardener), Jeremy Irons (Reversal of Fortune), Denzel Washington (Training Day), Sean Penn (Mystic River), Sean Connery (The Untouchables), Tommy Lee Jones (The Fugitive), Kevin Spacey (The Usual Suspects), Benicio Del Toro (Traffic), Tim Robbins (Mystic River), Javier Bardem (No Country for Old Men), Mark Rylance (Bridge of Spies).

Finally, there’s deniability. Because of the genre’s literary prestige, because of the tony talent behind and before the camera, and because of the genre’s ability to cross cultures, the thriller can be….more than a thriller. Just as critics hail every good mystery or spy novel as not just a thriller but literature, so we cinephiles have no problem considering Hitchcock films and Coen films and their ilk as potential masterpieces. On the most influential list of the fifty best films we find The Godfather and Godfather II, Mulholland Dr., Taxi Driver, and Psycho. At the very top is Vertigo, not only a superb thriller but purportedly the greatest film ever made.

I worried that perhaps this whole argument was an exercise in confirmation bias–finding what favors your hunch and ignoring counterexamples. Looking through lists of top releases, I was obliged to recognize that thrillers aren’t as highly rewarded in film culture as serious dramas (Manchester by the Sea, Moonlight, Paterson, Jackie, The Fits). But I also kept finding recent films I’d forgotten to mention (Hell or High Water, The Green Room) or didn’t know of (Karyn Kusama’s The Invitation, Mike Flanigan’s Hush). They supported the minimal intuition that thrillers play an important role in both independent and mainstream moviemaking.

And not just on the fringes or the second tier. Perhaps because film is such an accessible art, all movies are fair game for the canon. As a fan of thrillers in all variants, from genteel cozies and had-I-but-known tales to hard-boiled noir and warped psychodramas, I’m glad that we cinephiles have no problem ranking members of this mega-genre up there with the official classics of Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni (who built three movies around thriller premises). Of course other genres yield outstanding films as well. But we should be proud that cinema can offer works that aren’t merely “good of their kind” but good of any kind. For that reason alone, ambitious filmmakers are likely to persist in thrill-seeking.

Thanks to Kristin, Jeff Smith, and David Koepp for comments that helped me in this entry. Ben Hecht’s remark comes from Philip K. Scheuer, “A Town Called Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times (30 June 1940), C3.

You can get a fair sense of what the Brits thought a thriller was from a book by Basil Hogarth (great name), Writing Thrillers for Profit: A Practical Guide (London: Black, 1936). A very good survey of the mega-genre is Martin Rubin’s Thrillers (Cambridge University Press, 1999). David Koepp, screenwriter of Panic Room, has thoughts on the thriller film elsewhere on this blog.

Having just finished Delphine de Vigan’s Based on a True Story, I can see what attracted Assayas and Polanski. The film (which I haven’t yet seen) could be a nifty intersection of thriller conventions and the art-cinema aesthetic. As a gynocentric suspenser, though, the book doesn’t seem to me up to, say, Laura Lippman’s Life Sentences, a more densely constructed tale of a memoirist’s mind. And de Vigan’s central gimmick goes back quite a ways; to mention its predecessors would constitute a spoiler. For more on women’s suspense fiction, see “Deadlier than the male (novelist).” For more on Truffaut’s debt to the Hitchcock thriller, try this.

The Workshop (Cantet, 2017).