Archive for 2017

Going inside by staying outside: L’AVVENTURA on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

This month, our entry on FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel is a discussion of L’Avventura. This isn’t my favorite Antonioni movie, but it’s one I enjoy and admire—not least because of its striking originality of mise-en-scene. So that’s what I tackle in the Criterion entry.

The installment is here, and if you’re a subscriber you can watch it immediately. Otherwise, there’s a chance to sign up. If you’re not aware of FilmStruck, one of the great adventures in modern film culture, you can check on it here. (The Twitter feed is enjoyable even to non-tweeters like me.) Today, I want to flesh out my entry with some other comments. I hope they’ll be of interest even to those who aren’t signed on to the FilmStruck enterprise.

Two ways of doing deep

Le Amiche (1955).

During the 1950s, Antonioni displayed vigorous experimentation in visual style. Like many directors, he embraced the long take, usually in conjunction with camera movement. Within those parameters, he staged his action both laterally and in depth. But depth staging comes in many flavors.

One is the aggressive deep-focus technique of Welles, with large heads or objects very close to the camera in the foreground. Here are two famous instances from Citizen Kane (1941).

This fairly extreme approach was picked up by some 40s and 50s directors, especially those interested in what came to be called film noir.

You can find somewhat mild versions of these compositions in early Antonioni, especially in cramped surroundings. A bus ride and a necking party in I Vinti (1953) bring forth some big foregrounds.

Despite occasional shots like these, Antonioni’s early work favors an alternative approach to depth, the one cultivated by Jean Renoir, Mizoguchi Kenji, William Wyler, and others. That approach doesn’t go for Citizen Kane baroque. It keeps the foreground plane fairly distant–say a medium-shot or further–and uses both lateral and fairly deep staging to multiply key points of interest in the shot. Less fancy than the Welles tradition, it allows more naturalistic blocking because it yields more playing space.

Go back to I Vinti, and we’ll find that most shots aren’t as thrusting as Welles’ images, largely because of their reliance on real locations and naturalistic lighting. The film tends to stages its long takes in mid-range, porous compositions. A two-minute shot of teenagers lounging at a cafe and plotting a murder is rendered in a gentle diagonal that spreads out multiple points of interest.

By the way: Why doesn’t anybody make shots like this any more?

One advantage is that while the packed Wellesian frame tends to make its actors assume fixed poses, the more open frames of the alternative can show more of actors’ bodies and develop gestures and other actorly bits. This happens in the I Vinti café scene, which depends on characters’ changing postures, along with the distraction of the annoying little girl blowing on drink straws.

Similarly, Antonioni’s first feature, the noirish romance Story of a Love Affair (1950) makes adroit use of the mid-range foreground. The famous single-shot, 360-rdegree scene between lovers quarreling on a bridge is a paradigm case of how location filming can be made rigorous and purposeful. A complex camera camera movement is coordinated with figures resolutely evading each other in constantly varied medium-shots.

Le Amiche (1955) continues down the same path, with characters alotted distinct pockets of the frame to expose their fleeting reactions.

But there’s now a more intricate choreography, as befits a plot with several story lines. A scene gathering the major characters at a cafe is a magnificent exercise in the Wyler manner, with heads meticulously spotted across the frame.

For years I was surprised that L’Avventura (1960) and its successors La Notte (1961) and L’Eclisse (1962) make less use of this sort of precise staging in depth. While the director’s style remains fluid and rigorously patterned, and powerfully exploits urban vistas, it relies more on editing. But looking again at L’Avventura for the Criterion Channel installment, I became convinced that he was exploring a new way to handle staging—one that built upon his mastery of Renoir-Wyler choreography.

From the back or from the front

When a film’s narrative harbors mysteries, they’re often a matter of plot. Something has happened that we don’t fully know about, and the business of the plot is to bring that to light, either in the short term or across the whole movie. In the detective film, there’s a mysterious crime that needs solving, and the clarification will typically come at the climax, when the malefactor (and the motive, and the means) will get revealed. Plot-centered mysteries are easily dismissed as superficial, but the great tradition of literary detection shows that they can be imaginative and gripping, while also exploring literary techniques in sophisticated ways.

There are also mysteries of character—not just whodunit, but something deeper. A narrative might induce us to ask what makes characters do what they do. This can result in fairly superficial probing, as in many psychoanalytic films of the 1940s, but it can, again, prod the storyteller to exploit some aspects of the medium that engage us. At the limit, mysteries of character can lead the narrative to explore the moods and motives of its people, bringing out contradictions of mind and action. Even a potboiler like Gone Girl not only reveals the rage bubbling beneath Amy’s perfect porcelain surface but explains that anger as a response to the Cool Girl role dictated by yuppie culture.

I usually don’t employ the distinction plot vs. character when I’m thinking about film narratives, but as a first approximation it points up the nuances of L’Avventura’s visual strategies. The film has, initially, a clear-cut plot-based mystery: What has led Anna to disappear? Is she dead, or lost, or simply escaping from the situation? This is, in a way, the bait luring us to pursue mysteries of character.

What, to start, does Anna want from her affair with Sandro? She seems alternately flirtatious, cynical, angry, and passionate. And assuming her disappearance wasn’t accidental, what impelled her to leave the party? As for Sandro, what sort of man is he? And why does he, with unseemly haste after Anna’s vanishing, seize Claudia and kiss her violently?

Claudia, for her part, seems to gradually accept her role as the Anna substitute. We’d expect her to be torn by her betrayal of her friend, and maybe she is, but we can’t be sure. With almost no backstory supplied for these people and no plunge into their inner lives through dreams, voice-over, subjective visions, and the like, we’re forced to read their minds and hearts on the basis of what they say and do. This is relentlessly behaviorist cinema.

Here’s where visual style kicks in, I think. Antonioni declared his interest in moving the Neorealist impulse from social observation to psychological revelation.

The neorealism of the postwar period, when reality was what it was, so intensely present, focused on the relationship between characters and reality. What was important was that very relationship, which created a cinema based on “situations.” . . . That’s why, nowadays it’s no longer important to make a film about a man whose bicycle has been stolen. . . . It is important to see what is inside this man whose bicycle was stolen, what are his thoughts, what are his feelings.

How to achieve this psychological penetration? Not through the sort of definite scene structure of a Hollywood film, a crisp slice of action that can be summed up in a story beat.

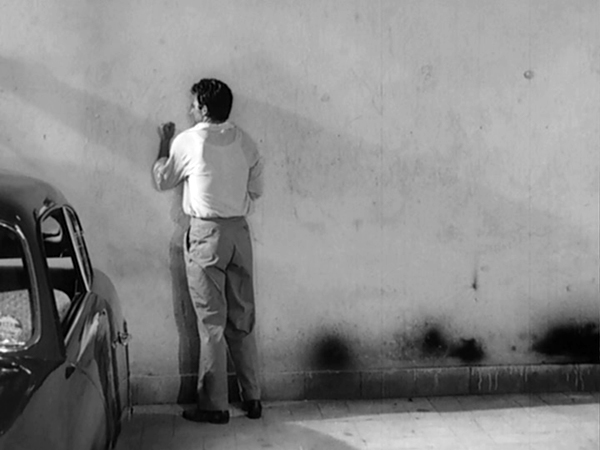

I believe it is much more cinematic to try and capture the thoughts of a person through an ordinary visual reaction, rather than enclose them in a sentence. . . . One of my concerns in filming is to follow the characters until I feel it is time to stop. . . When all has been said, when the main scene is over, there are less important moments; and to me, it seems worthwhile to show the character right in these moments, from the back or the front, focusing on a gesture, on an attitude.

Antonioni scenes, critics sometimes say, begin a bit before they start and end a bit after they stop.

You might expect from this emphasis on character psychology and the habit of lingering on a scene’s resonance would yield few mysteries. Yet what interests me in L’Avventura is the way in which it doesn’t allow us to “see what is inside” its characters. Perversely, having braked the dramatic momentum in order to probe character, Antonioni goes on to block our access to his people’s minds.

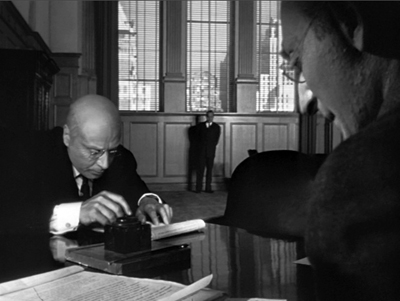

His visual strategies for doing this are many, and they’re flaunted in the film made just before L’Avventura. The witholding of character reaction is flamboyant in Il Grido (1957), maybe over the top.

L’Avventura‘s reticent pictorial strategies are more nuanced and naturalistic, and my FilmStruck contribution tries to chart them. For about the first hour of the film, Antonioni lets landscape overwhelms his characters, gives them equivocal facial expressions, refuses the full information of shot/reverse shot cutting, and at crucial moments simply makes his actors turn from the camera, denying us access to their emotional reactions.

What’s just as interesting, the second half of the film selectively returns to the techniques that were initially banned. It’s as if these more familiar image schemas–reverse shots, frontal close-ups, more marked facial reactions–have become suitable to the growing romance between Claudia and Sandro. Now the first hour’s stingy attitude toward psychological information is balanced by a greater degree of emotional exposure, especially on Claudia’s part. By the very end, the two broad strategies coexist uneasily, and some enigmas remain.

During the late 1960s Antonioni changed his style. He turned from deep-focus, wide-angle images to flat telephoto ones, and he began relying on a pan-and-zoom technique. These were partly responses to shooting in color and wider formats, I think, but they also offered the opportunity for a painterly look that he exploited in the films from Red Desert (1964) on. Fellini, Bergman, Visconti, and others took a similar path, as I tried to show in this early blog post.

In 1960 those developments were yet to come. It seems to me that the style of L’Avventura enhances the mysteries of plot and character in a unique and unsettling way. We get a visual surface that entrances us with its measured beauty and teases us with its calm opacity.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the Criterion team for including us in their FilmStruck enterprise.

My quotation from Antonioni comes from his essay “My Experience [1958],” in his book The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema (Marsilio, 1996), 7-9.

The L’Avventura discussion on FilmStruck is the fourth in our Criterion Channel series, “Observations on Film Art.” The others are Jeff Smith on the music of Foreign Correspondent, me on Sanshiro Sugata, and Kristin on landscape in Kiarostami. Some clip extracts can be found here and here. Jeff has amplified his installment with further comments on this blog, and I’ve done the same with Sanshiro , as today with L’Avventura. We introduce our collaboration in this entry. The Criterion introduction to us is here.

For more on Mizoguchi’s approach to depth staging, see this summary entry. There’s more on Wyler’s style here. I compare the two directors in this entry on sleeves. I discuss the broader shift from deep-focus techniques to pan-and-zoom ones in On the History of Film Style, Chapter 6.

I Vinti.

My cover is blown

DB here:

The University of Chicago Press has come up with a cover for my new book, due in September. It’s a bit in-your-face, but I guess that suits the subject. I just hope it doesn’t predict readers’ reactions to the text.

Here’s a version of the jacket copy.

Early in the 1940s American movies changed. Flashbacks began to be used in outrageous, unpredictable ways. Soundtracks flaunted voice-over commentary, and characters might pivot from a scene to address the viewer. Incidents were replayed from different characters’ viewpoints, and sometimes those versions proved to be false.

Films now plunged viewers into characters’ memories, dreams, and hallucinations. Some films didn’t have protagonists, while others centered on anti-heroes or psychopaths. Women might be on the verge of madness, and neurotic heroes lurched into violent confrontations. Combining many of these ingredients, a new genre emerged—the psychological thriller, populated by women in peril and innocent bystanders targeted for death.

If this sounds like today’s cinema, that’s because it is. In Reinventing Hollywood, David Bordwell examines for the first time the full range and depth of trends that crystallized into traditions. He shows how the Christopher Nolans and Quentin Tarantinos of today owe an immense debt to the dynamic, occasionally delirious narrative experiments of the Forties.

Bordwell examines how a booming movie market during World War II allowed ambitious writers and directors to push narrative boundaries. Those experiments are usually credited to the influence of Citizen Kane, but Bordwell shows that the experimental impulse had begun much earlier.

Many of the general strategies had been explored in the silent era, but they had gone into eclipse with the coming of sound. Meanwhile, similar techniques were surfacing in radio, fiction, and theatre and soon migrated to cinema. It was during the 1940s that filmmakers had the opportunity to consolidate these storytelling ideas and press them to new limits.

Despite the postwar recession in the industry, the momentum for innovation didn’t slacken. Some of the boldest films of the era came in the late forties and early fifties, as filmmakers sought to outdo their peers.

Through in-depth analyses of films both famous and virtually unknown, from Our Town and All About Eve to Swell Guy and The Guilt of Janet Ames, from film noirs to Disney animation, Bordwell assesses the era’s unique achievements and its legacy for future filmmakers. The result is an in-depth study of how Hollywood storytelling became a more complex art.

I was lucky in my outside readers, who offered me many good suggestions for improving the book. They were also kind enough to say nice things about it. Here’s Malcolm Turvey, a major scholar of the history of experimental film:

In addition to the almost unparalleled breadth and depth of his research, Bordwell’s love of and admiration for the period’s formal experimentation and risk-taking comes through on every page. His exuberance is infectious…. Just as importantly, I know of no other work like this in my field due to its strikingly novel view of creation in popular culture.

Similarly, James Naremore, distinguished critic-historian of Hollywood, gave me confidence in what I was doing with comments like this:

[This is] a remarkable book that I recommend unreservedly for publication. The manuscript was a special pleasure to read because, like Bordwell, I’m a great fan of the studio pictures of the 1940s, which in my opinion are the beating heart of American cinema. No other critic or historian has come close to the sort of comprehensive discussion Bordwell gives of the period. . . . Despite all this, there isn’t a whiff of academic or belles-lettrist pretention in his writing. Like The Rhapsodes, his recent Chicago book about film criticism in the 1940s, this manuscript is not only lucid but also witty and engaging, written with flair.

Speaking of covers, check out the one adorning Jim’s forthcoming book on Charles Burnett.

Speaking of covers, check out the one adorning Jim’s forthcoming book on Charles Burnett.

In a future entry I’ll post the table of contents, but if you want to get the flavor of what I’m doing, you could look at these blog entries: “Chinese boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies”; “They see dead people”; “Dead man talking”; “Innovation by accident”; and of course the entries on The Chase starting here. For arguments about the continuity of Forties strategies in current film, there’s “The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks,” as well as this recent entry. For a complete inventory, check the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Reinventing Hollywood will be published in hardcover first, paperback later. As a reader, I usually don’t favor this policy, but in this case the price is decent ($40) for a book of 160,000 words, 550 pages not counting the index, and many pictures. It can be preordered here.

And yes, there will be a website with clips, so you can follow along with the book’s discussions.

Note to fussbudgets (like me): The cover photo is from Sudden Fear from 1952, but it’s okay because the period the book covers runs from 1939 to 1952 (The Long Forties, I guess.) I talk about the film in this entry.

A Letter to Three Wives (1948).

The Oscars’ Best Picture and other Best Picture

Barry Jenkins

Kristin here:

No, I’m not referring to the mistake that led to two different titles being read out as Best Picture recipients in the chaotic final minutes of this year’s broadcast of the Academy Awards. That error has drawn huge amounts of attention from the media. But other more interesting aspects of the pattern of winners have been largely ignored.

The explanation for the mess-up has turned out to be that there are two duplicate stacks of those sealed and highly guarded envelopes, one on either side of the stage, so that presenters can be handed whichever envelope they are supposed to have, with the duplicate one on the other side being discarded. Apparently one of the PwC (formerly known as PricewaterhouseCooper) partners was so gobsmacked by seeing Emma Stone backstage at the ceremony that he was more concerned to tweet a photo of her than to make sure that the duplicate envelope for her category got removed from the stack on the side of the stage he was tending. Still being atop the stack, it ended up being given to Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, who were to announce the Best Picture winner.

This image is deleted but not forgotten.

Well, there’s a simple remedy for the problem. Have all the presenters enter from the same side (the winners all exit toward the same side, after all) and have just one set of envelopes with two people keeping track of them in case one gets starstruck.

Beyond the kerfuffle

But more interesting to me was the rather odd imbalance in the awards for the top winners. La La Land was widely expected to garner Best Picture, and it won in six of its potential thirteen categories. (Two of its songs were nominated and competing against each other, so the film could not have won on all fourteen nominations.) Those included some pretty important categories: Best Actress, Director, Cinematography, Score, Song, and Production Design. Moonlight won three out of its eight nominations: Best Picture, Supporting Actor, and Adapted Script.

It seemed to me that we have seen other similar results in recent years, and the reason is clearly political. For decades the assumption was the the Academy consisted of members of the filmmaking profession awarding each other statuettes on the basis of technical and artistic excellence. Aesthetic criteria ruled, though the middlebrow tastes of a lot of the Academy members tended to fasten on quite conventional sorts of mainstream films.

The movies that won Best Picture were typically serious items made by the big studios. Historical epics (Gladiator, Titanic), biopics (A Beautiful Mind), dramas (The English Patient, American Beauty), auteur pictures (No Country for Old Men, The Departed), and the occasional relatively lightweight item somehow steamrollered through by Harvey Weinstein (Shakespeare in Love, The King’s Speech). Genre films might get nominated but they seldom won. The Lord of the Rings astonished fans by actually receiving seventeen Oscars over three annual parts, including Best Picture for The Return of the King.

Most of the nominated films were noted neither for their diversity of characters and cast nor for their progressive politics.

In recent years, however, the political implications of filmmaking and the Oscars have become far more high-profile. The country has paid the price for electing its first black president by witnessing the surfacing of a racist backlash so extreme that few would have believed it possible. The shooting of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014 and the events that followed called attention to a blight that has stayed with us, the needless killing of black men and boys and women, with the officers involved seldom being charged with any crime. The hugely unfair incarceration rate of black people. The horrendous rise in attacks against virtually any non-white, non-Christian group in this country unleashed by the “election” of T***p. And the concealment of widespread domestic terrorism, which in body counts (including those of peace officers) far outweigh the purported threats from the Middle East.

The result, I think, is a greater consciousness of political content, and specifically progressive content, among the Academy members. Three times in the past four Oscar presentations, there have in a sense been two winners. One film is judged more on the technical and artistic grounds and given a larger number of awards but not Best Picture. Another film with an important political theme at its core receives a distinctly smaller number, including Best Picture. The practice seems to imply that the voters want to give the top award to two films, and they have somehow collectively found a way to do so.

Three recent examples

The first of the three split decisions was for the 2013 releases, when Gravity was up against 12 Years a Slave. Despite being in the science-fiction genre, Gravity (here and here) was so innovative and sophisticated in the technology that created such a perfect illusion of outer space that it won seven of the ten categories in which it was nominated. These were Director, Cinematography, Editing, Score, Sound Editing, Sound Mixing, and Visual Effects.

12 Years a Slave, made by an established and respected black director, Steve McQueen (above with his producer’s Oscar), was nominated for eight Oscars and took three: Best Picture, Adapted Screenplay, and Supporting Actress, for Lupita Nyong’o. The implication seemed clear. A film could be best because it was so well made or best because its content was so politically important. Which is not to say that a single film could not be both, and that may well happen.

It’s also not to say that 12 Years a Slave and the other politically oriented films I mention in this entry are not well made. Any film that achieves the rarefied heights of Oscar nominations is likely to be very well made. The politically daring films, however, tend to be indies with relatively small budgets and hence less access to complex technology and fancy sets and costumes. The big studios that do have such access are not exactly noted for the daring ideology of their releases. (The recent fuss over the fact that a Disney film, the upcoming live-action Beauty and the Beast, has a gay character in it is testimony to that.)

The same thing did not happen in 2014, when Birdman won Best Picture, as well as Director (for a Latino, Alejandro Iñárritu), Original Screenplay, and Cinematography. The main politically oriented film nominated for Best Picture was Ava DuVernay’s Selma, which won only in its one other category, Best Song. One might also want to put The Imitation Game, with its gay protagonist, into the political category. It was nominated in eight categories, winning only Adapted Screenplay. This was the year when the paucity of black nominees led BroadwayBlack.com managing editor April Reign to launch #OscarsSoWhite. The protest and its hashtag became more prominent in response to the lack of African American nominees from 2015 films. The Academy responded with some changes to its membership and rules.

The 2015 Oscars made the divide between the two “best pictures” clearer. The action film Mad Max: Fury Road was both widely praised and popular, and surprisingly enough, it won in six of its ten nominated categories. These were Costumes, Editing, Makeup/Hairstyling, Production Design, Sound Editing and Sound Mixing. It lost Best Picture, Director, Cinematography, and Special Effects.

Spotlight, with its focus on sexual abuse by Catholic priests, was nominated for six Oscars and won only two: Best Picture and, as inevitably happens in the cases of political films, Original Screenplay. It lost Director, Supporting Actor, Supporting Actress, and Film Editing. With a genre film and a political one both rewarded, the Academy also honored a more traditional prestigious drama and gave The Revenant Best Director, Actor, and Cinematography.

Then came Moonlight in 2016, with its combination of black and gay subject matter, to broaden the Oscars’ horizons even further. (The other film directed by a black actor, Denzel Washington, who was not nominated in that category, won Best Supporting Actress for Viola Davis.)

How did we get here?

This pattern is not entirely new. It’s just happening more frequently and obviously. It has been creeping up on us for a little over a decade now. The prominence of a politically based set of awards began to emerge, I suspect, in 2005 with Brokeback Mountain (bottom). It received eight nominations, including Best Picture, and won Director, Score, and Adapted Screenplay. It was widely perceived to have lost the top award to Crash because of opposition to its gay subject matter. Crash, which dealt with race relations in a way that divided critics and audiences, won Best Picture, Original Screenplay, and Film Editing.

To some extent Juno, nominated in 2007 for Best Picture, Original Screenplay (its only win), and Actress, fits into the political pattern, with its focus on abortion. It straddled the liberal line, with the heroine deciding against abortion but the film treating this as a matter of choice. No Country for Old Men won Best Picture as well as three other awards among its eight nominations: Director, Adapted Screenplay, and Supporting Actor (a Spanish actor, Javier Bardem playing a character who might be Mexican).

The political nominee in 2008 was Milk (above), with its sympathetic gay theme. Of its eight nominations, it won Best Original Screenplay and Actor. By then the association of a best-screenplay award with a liberal (or semi-liberal) film was firmly in place. Slumdog Millionaire took Best Picture and eight other Oscars.

2009 was the year when the Academy extended the Best Picture category to a potential ten, the idea being to boost the ratings of the television broadcast of the awards ceremony. Supposedly, now blockbusters would be nominated alongside the more prestigious dramas, biopics, and indie breakout films. (In practice, only 2009 and 2010 saw ten nominations. There were nine in 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2016, and eight in 2014 and 2015.) To some extent that plan worked, with Avatar gaining a nomination. There was also room for animated films, with Up being nominated in both Best Picture and Animated Feature categories (as Toy Story 3 was in 2010).

But as one would expect, small indie films, some of them politically oriented, filled out the list. One of them, The Hurt Locker, had grossed just under $50 million worldwide, compared with Avatar‘s nearly $2.8 billion (still the highest-grossing film of all time). The Hurt Locker was an anti-war film, but the main political punch to the broadcast was the question of whether Kathryn Bigelow would become the first female director of a Best Picture winner–with the added spice of her most obvious competitor, James Cameron, being her ex-husband. She did.

That same year, however, another film more closely fitting the political pattern was nominated: Precious, with six nominations including Best Picture. It was the first of these socially-conscious films to deal primarily with African American characters, and although it did not win Best Picture, it received the by-then-familiar consolation prizes of Best Adapted Screenplay and Supporting Actress (with a standing ovation for Mo’Nique when she took the stage to pick up her Oscar). Would Precious have been nominated for Best Picture without the newly capacious category? It’s anyone’s guess.

The pattern did not continue for the next few years. The Kids Are All Right, with its lesbian central couple, was the closest that the 2010 Best Picture nominees had to a political contender. It was nominated for the established categories: Best Picture, Original Screenplay, Supporting Actor, and Supporting Actress. It won none of them. 2011 saw The Help, with a mixed black and white cast, get nominated for Best Picture, as well as Actress (Viola Davis’ first nomination) and two competing Supporting Actress nods (Octavia Spencer won the film’s only Oscar over Jessica Chastain). Harvey Weinstein again triumphed with The Artist, which won Best Picture, as well as Director, Actor, Costume, and Original Score of its original ten nominations.

For 2012, two black-themed films were nominated for Best Picture. Beasts of the Southern Wild garnered three additional nominations with no wins: Director, Original Screenplay, and Actress. Django Unchained got four other nominations, winning Original Screenplay and Supporting Actor. Argo won Best Picture, Adapted Screenplay, and Film Editing out of its seven nominations.

Then 2013 brought the win for 12 Years a Slave.

Perhaps it’s just a coincidence that in recent years we have seen three politically daring films win Best Picture while only gaining one or two other awards. As with political films from Brokeback Mountain on, those awards tend to include one for the screenplay, adapted or original, as if the voters are trying to emphasize that the film is important primarily because of its subject. There is usually an acting award as well, more often in a supporting role. Interestingly Hidden Figures, which didn’t win any Oscars, was nominated in those same three categories: Best Picture, Adapted Screenplay, and Supporting Actress.

Will Academy voters continue delicately dividing the awards in order to stress the importance of two films? The tactic tends to give a bunch of awards to a very popular film and a few–including the most prestigious one–to a film that the voters are in effect encouraging more people to see. There’s something to be said for doing so.

Politics and the foreign-language Oscar

For a long time it was assumed that this year the German comedy Toni Erdmann had this category sewn up. Then, T***p signed his first anti-Muslim immigration ban just a few days after the Oscar nominations were announced. Iranian director Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman was in the list of foreign-language nominees. (He had previously won in the same category for A Separation in 2011.) Farhadi announced that in protest of the ban, and probably through legitimate concerns that he would not be admitted to the country, he would not attend the Academy’s ceremony. Speculation began to circulate that Academy members might vote for his film in solidarity. The Salesman won the Oscar, though to what extent this was a move by those members against the ban is unclear. I personally enjoyed and admired Toni Erdmann, but I consider The Salesman a better film.

As film critic Bilge Ebiri has pointed out, strongly political foreign films have not typically won in this category. Still, voting rules have changed:

Academy members get screeners in the mail, and they need not prove that they’ve seen all, or in fact any, of the nominees before they send their ballots. That could mean a surge of people voting for The Salesman simply because they’re looking to stick it to Trump.

But there might be more far-reaching implications for a Farhadi win. The Muslim world has undergone a filmmaking renaissance in recent decades. Much of this began with the work of Iranian directors in the 1980s and ’90s, but it has since expanded to the rest of the Middle East and North Africa. For many years, Oscar failed to recognize these works. Abbas Kiarostami, who died in July, was the most important figure of the New Iranian Cinema and an undisputed giant of international film but notably was never nominated.

Slowly, however, the Academy has been noticing. Last year, Turkish director Deniz Gamze Erguven’s Mustang, about the plight of young women in Turkey, was a nominee (albeit as a French submission) alongside Jordanian director Naji Abu Nowar’s gripping World War I drama Theeb. During the past decade, directors including Palestine’s Abu-Assad and Algeria’s Rachid Bouchareb have vied for statuettes multiple times. And the more visible people are, the harder they become to demonize.

In that sense, a win for Farhadi would mean more than just a repudiation of a specific presidential decree. It would help to push further into the spotlight a cultural revolution that has been happening for years now. In doing so, it would be the ultimate assertion of a people’s humanity. And sadly, we now live in a world where that indeed is a political act.

The fact that for a time Iran had one of the most exciting national cinemas in the world has remained largely overlooked, even by many admirers of foreign cinema. I don’t have much hope that that tradition and the more recent films of directors like Farhadi and Jafar Panahi will become widely known. Still, some people will take note. Watching the great Iranian films of the past few decades would reveal the humane, touching stories that their makers tell–and watching Middle Eastern films in general could, as Ebiri says, remove the knee-jerk demonizing of people from that region. After all, the vast majority of Muslims fear and hate the extremists and terrorists as much as anyone else does.

The Oscars are not all that important in the larger scheme of things. In recent years they have been increasingly hyped, and media chatter about them has become a year-round phenomenon that drives out a lot of serious news about the film industry. (It’s cheaper to have an employee watch some films and go on and on about their Oscar prospects than to finance them going out and reporting on things.) Only the naive think that the actual best films made in the world in any given year get the Oscars.

But clearly the Oscars do matter to people who are trying to use them as a tool to pressure the industry into introducing more diversity into the kinds of subjects that provide stories and into the range of people who work in front of and behind Hollywood’s cameras. It seems to be affecting the industry to some extent, at least for African Americans. Now, can it work for other under-represented groups? For discussions of that question, see Variety‘s post-Oscars coverage here and here.

March 13: Thanks for Ivan Nunes for a factual correction.

Brokeback Mountain

Waldo Lydecker, James Schamus, and 1910s movie storytelling

Laura (1944).

DB here (in DC):

Over the next two weeks I’m involved with several events during my stay at the John W. Kluge Center of the Library of Congress. If you’re near Washington, do consider coming to one or all of these doings.

First up is a screening of a sparkling restored print of Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944), at the gorgeous Packard Campus Theater in Culpeper, Virginia on 8 March. The show, a new addition to the Theater’s spring schedule, starts at 7:00 pm, a half-hour earlier than the customary time. I’ll be giving a brief introduction.

On the following Monday, 13 March, the Kluge Center will host “James Schamus on Philip Roth and the Art of Adaptation.” After a screening of James’s directorial debut Indignation, he will participate in a discussion with the audience. I’ll play moderator. The event will take place at 3:00 pm in the Pickford Theater, on the third floor of the Library’s Madison Building, 101 Independence Ave. S.E.

James, professor at Columbia and producer and writer of many important American and Chinese films, needs no introduction to this blog’s readership. (Above, he’s with frequent collaborator Ang Lee.) We’ve celebrated his work here, and I discussed the admirable Indignation just last summer. This upcoming session should be an exhilarating afternoon.

Lastly, I’m giving a talk, “Studying Early Hollywood: The Search for a Storytelling Style.” It develops some of the issues I’ve floated in my books, other lectures, this video lecture, and most recently this blog entry. The talk is set for 4 pm. on Thursday, 16 March. It takes place in room 119, a magnificent venue on the first floor of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, 10 First St. S.E.

All these events are free and open to the public, and you don’t need tickets.

Being at the Kluge Center has been very stimulating, and my research into 1910s visual style has benefited hugely from access to the LoC’s film collections. These three events are wonderful ways to wrap up a stay that has gone by all too fast. If you’re in the vicinity, come by and say hello.

Thanks to the many people who have made these events happen: At the Kluge Center Ted Widmer, Mary Lou Reker, Dan Turello, Travis Hensley, and Emily Coccia; at the Packard Campus Greg Lukow, Mike Mashon (initiator of many things), and David Pierce.

More information on the Packard Campus Theater is here. A summary of James’s vast career is here.

The Packard Campus Theatre. Photo by Glenn Fleishman.