Archive for 2017

How LA LA LAND is made

La La Land (2016).

The formal method is fundamentally simple. It’s the return to craft (masterstvo).

Viktor Shkovsky, 1923

DB here:

Not how it was made. We’ll get “The Making of La La Land” as a DVD bonus, and there are already behind-the-scenes promos.

No, this is about how it is made.

On this site, we mostly practice a criticism of enthusiasm. We write about what we like, or at least about films that intrigue us from the standpoint of history or aesthetics. Sometimes, what interests us intersects with a current controversy. Take La La Land.

Some of my cinephile friends disapprove of it. It swipes too much, they say, from classic studio musicals and the work of Demy, and it doesn’t live up to either model. But tastes change. I remember when the classic musicals that we venerate were considered fluff, and I recall how Demy’s films, especially Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, were held at arm’s length by many of my 60s pals. “He tries too hard,” a friend remarked. Some say that about Chazelle, and perhaps in a few decades La La Land will be remembered fondly.

In any case, I’m not aiming to denounce this ambitious, agreeable film. I’m more interested in asking how La La Land accords with the craft of studio musicals and Demy’s efforts. I’m also interested in tracing its affinity with a third tradition of song-and-dance: the Broadway show.

Along all three dimensions, I hope to take Shklovsky’s advice and ask about craft. La La Land is both derivative and original. Actually, most movies are, though in various proportions.

The song plot

If we want to understand how film form and style work, we can’t neglect the nuts and bolts of moviemaking. In trying to achieve particular effects, filmmakers have created craft traditions, favored options bounded by loose limits. Mostly these traditions grow up intuitively, as solutions that just feel right. In any case, behind the cluster of preferred practices we can often find principles of design and execution that can be made explicit.

A lot of what Kristin and I have been doing since the 1970s consists of trying to bring to the surface filmmakers’ underlying habits and conventions. Those help shape how viewers respond to films. We aren’t maniacs for systematization—art can’t be utterly systematized—but as analysts we want to discern patterns of story and style, what earlier entries have called schemas. And as historians we want to understand how patterns of story and style get passed down from earlier films, and passed around among contemporaries.

For example, some narrative schemas of American studio cinema are what I aim to lay bare in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. Without invoking the big guns of theory, I try to point out how craft traditions of plotting and narration got recast in those crucial years. A recent entry hereabouts tries to show the legacy of those years surfacing in current releases, La La Land included.

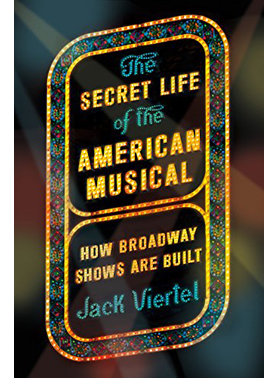

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

What Viertel brings to the table is the “song plot,” a sequence of musical numbers that has become conventional in Broadway shows. Often, of course, many numbers enhance the dramatic action, but sometimes they’re inserted for a change of mood or a burst of energy. The song plot both echoes the action plot and provides its own arc of pleasure, with musical numbers that may be more or less extraneous to the main action.

What makes Viertel’s anatomy of shows interesting is that even the narratively “irrelevant” numbers tend to occur in the same spot from show to show, and they have a common emotional quality. They aren’t just “spectacle interrupting narrative,” to use a film-studies commonplace. As spectacle, they have their own pattern, and that’s gratifying alongside the pleasures of the story. Viertel’s macro-schema is probably known to many insiders and fans, but it was all news to me, and it helps me understand the musical spine of this recent movie.

Hence today’s title, of an entry that is 100% spoiler-filled. I’ll consider La La Land as a classically constructed film. Then I’ll test its “making” against Viertel’s template of a musical. I conclude with some remarks on how analyzing these patterns highlights the movie’s variance from adjacent traditions.

From meet-cute to remeet, and re-remeet

Start with the Hollywood plot structure. Kristin has argued that even though mainstream American screenwriters sometimes claim to be following a three-act plot model, their craft practice often pushes them to a four-part schema. (She has discussed this here, and I’ve given examples here and here.) Specifically, the long second “act” is usefully thought of as two separate parts split by the film’s midpoint.

The conventional plot pattern consists of a Setup in which protagonists define their goals; a Complicating Action that redefines those goals; a Development that muddles, delays, or intensifies the goals; and a Climax that resolves them. These parts typically run 20-30 minutes, and films of varying lengths, long or short, can include more or fewer parts than these four. In most cases there will also be an epilogue or “tag.”

La La Land runs almost exactly 120 minutes, not counting the opening logos or the end credits. The Setup (running 25 minutes) establishes Mia and Sebastian as dual protagonists, caught in the midst of the initial traffic jam.

We then follow Mia through her day as a barista, her failed audition, her return to her apartment, and her agreement to go out to a networking party with her flatmates.

A flashback returns us to the traffic jam, and now we follow Sebastian to his apartment, where in a parallel to Mia’s day he makes coffee, rummages through unpaid bills, and talks with his sister. He goes on to his job as pianist playing Christmas music at a cocktail bar. Mia, who’s come in by accident, stands before him, moved by his switch into improvised jazz. But Sebastian is fired, and disgruntled, he coldly bumps past her.

The Complicating Action starts after Mia fails another audition. She goes to a pool party and sees Sebastian in the ensemble. She teases him, and they leave the party together. Although there’s friction between them, they start a friendship. They confess their dreams: she wants to be an actress and he wants to start a club that hosts classic jazz.

Mia absentmindedly agrees to go to a movie with him on a night she has a date with her boyfriend. But she’s haunted by Sebastian’s music and she finds him at the theatre, watching Rebel without a Cause. They go to the planetarium featured in the film and kiss. At the end of the Complicating Action, about 60 minutes in, Mia resolves to write a one-woman show for herself.

The Development is the stretch where backstory is introduced, obstacles create delays, and subplots intertwine with the main action. Since in La La Land the romance seems solid (there are no love rivals), and there are no secondary characters of consequence, the film is devoted to the other major plotline: the obstacles encountered in our couple’s quest for success. Those in turn affect the romance.

A Development also typically relies on montage sequences, and we get plenty here. Mia works on her show, while Sebastian is offered a chance to join his friend Keith’s combo. To stabilize his life with Mia, he takes the job.

Soon he’s on tour, and the band finds some success, though he’s compromising his principles. “Do you like the music you play?” Mia demands, and he evades answering. The crisis comes when a photo shoot delays his arrival at her premiere, which is a fiasco.

Mia declares: “It’s over”—meaning both her career and their affair. She goes back home. We’re at the 90-minute mark.

We’re ready for the Climax, which is often driven by a deadline. Sebastian takes the call asking Mia to audition, and he rushes her back to it. She gets the part, and the two of them decide to wait and see how their relationship develops.

Five years later, Mia is now a success. This seems an abrupt, even anti-climactic turn of events, coming only eleven minutes after the Climax started. Apparently, despite their declarations of undying love, the couple’s romance was never rekindled. We see Mia visit the café where she was once a barista and return to her hotel and her husband and daughter. Her activities are crosscut with glimpses of Sebastian alone in his apartment. In effect, this passage balances our alternating introduction to the couple during the Setup.

Mia and her husband drop in on a club that turns out to be Sebastian’s. Mia and Sebastian eye each other longingly. Mia watches him play Their Song, and this launches an apparently shared fantasy of an alternate-world climax and resolution.

There’s a replay of the two of them at the cocktail bar, but this time Sebastian doesn’t brush past her. They kiss passionately. After this what-if premise, the race to the audition is replayed in stylized form, and the trajectory of Mia’s career—going to Paris, finding screen success, forming a family—is reenacted with Sebastian as her mate. At the end, Sebastian, not her husband, is sitting with her in the club (listening in effect to himself), and they kiss.

This soufflé of flashbacks and fantasies ends the plot on the conventional romantic clinch. But the film’s tag, of course, is their return to reality and the sad smiles shared as she goes off with her husband. In all, this double climax/ resolution turns out to run almost thirty minutes, which would be unusually long for a non-musical.

As is customary in Hollywood narrative, motifs and parallels crisscross the film. The opening song on the freeway lays out hints of what is to come. The sequence alternates a woman singing about a career as a film star (“It called me to be on that screen”) and a man singing about a career honoring old music (“ballads in the bar rooms left by those who came before”). Anticipating the finale, the woman’s song includes mention of a boy seeing her on the screen and remembering that he knew her.

More parallels and rhymes follow. Mia nearly stands up Sebastian on their date; he misses her show. Each encourages the other to keep struggling. Mia’s blockhead boyfriend anticipates her eventual GQ husband, as if she has decided not to go for the edgy type Sebastian is. The motif of Mia’s beloved aunt, who inspired her love of movies and her urge to act, gets dramatized twice, once in her one-woman show and more successfully in her audition song, “Here’s to the Ones Who Dream,” which wins Mia the movie part.

So many things are doubled that it’s not surprising that the Setup parallels each protagonist’s day and establishes the crucial moment at the supper club. That too gets replayed—once in the real world, as she and her husband hear Sebastian’s performance of his tune for her, and once at the start of the fantasy projection of their future, which becomes a replay of her actual life with her husband.

So far, so classical. But—duh, as they say–La La Land is also a musical.

That’s the Broadway melodies

My outline of La La Land‘s construction is fairly hollow, and could be filled in with closer consideration of the moment-by-moment process of conflict and change, or the flow of information as we’re attached to one character or the other. But we get access to another layer of “making” by considering the film as a musical–more specifically, a Broadway musical. (No surprise that the lyricists are stage-based.) Viertel is a big help here. His account of the prototypical song plot fits La La Land fairly well, and the places where it doesn’t are pretty interesting too.

Broadway shows of the Golden Age (roughly 1942-1975) tend to have the double plotline characteristic of Hollywood films. Both shows and movies make romance central, and this permits the action plot and the song plot to fit together. In Broadway shows, as in many films, paired protagonists try to find happiness in both love and work. Intertwined goals are central to getting the action moving, and so goals are ingredient to the song plot.

Director Damien Chazelle apparently hesitated about opening with the freeway-gridlock number, but he and editor Tom Cross decided to announce the film’s song-and-dance premises immediately. I think the pressure of show-biz tradition helped. According to Viertel, the prototypical musical might start with a solo, as with Oklahoma!’s “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’.” But it may also start with a “blowout,” and La La Land’s “Another Day of Sun” surely counts as that. It establishes milieu and mood, in somewhat the manner of the bouncy introduction to Damon Runyon’s world in Guys and Dolls, and it announces the central goal of showbiz success.

Viertel marks the next number as crucial. It’s the “I Want” song, the initial crystallizing of the protagonist’s goals. In La La Land, that position is occupied by “Someone in the Crowd,” which starts as an ensemble number with Mia’s brassy roommates but devolves into a solo for her. By then, the “someone” she seeks isn’t only a career-enhancing meetup but a love partner.

After the plot moves into the Complicating Action phase, Mia and Sebastian meet cute again at the pool party. He’s playing in a lame retro band and she teases him, in revenge for his brushoff at the piano bar. There follows the next key item in the song plot, what Viertel calls “the conditional love song.” The prototype is “If I Loved You” (Carousel). Essentially it declares how wrong the boy and girl are for each other. It has the function of blocking and deferring the goals of the love plotline, and in non-musical rom-coms, it takes the shape of verbal sparring, quarrels, and competition (as in, say, You’ve Got Mail).

Clearly, “A Lovely Night” is a conditional love song, as Mia and Sebastian remark on how the LA view would be perfect for a couple who were really in love. But as often happens, while the words refuse romance, the music and the choreography show that the two ought to be together.

At this point in the song plot, Viertel suggests, the show needs a burst of energy. In La La Land, what he calls The Noise is delivered by the instrumental number at the jazz club, called in the soundtrack album “Herman’s Habit.” It’s not narratively gratuitous, as it’s an AV demo of the sweet collective creativity Sebastian admires in classic jazz. The number also marks Mia’s growing affection for Sebastian and her belief in his dream.

But now Viertel’s Broadway template diverges from La La Land, and it points up a crucial factor in the film. The conventional song plot typically devotes a number to a second couple or a subplot. Think of the comic couple in The Pajama Game, and the number “I’ll Never Be Jealous Again,” which expresses Hines’s unreasonable fear of losing Gladys. That show also includes the subplot of labor negotiations with the devious Mr. Hasler. But La La Land doesn’t have a subplot involving a second couple, a romantic triangle, or a villain. So no such song appears.

Next on the Viertel template is a star turn, a distinctive number for one of the major players. That function is fulfilled by “City of Stars,” the introspective musing of Sebastian on the pier. Viertel indicates that the following number tends to be a high-energy tentpole that starts the buildup to the first-act curtain. That position is occupied by the airy pas de deux at the Griffith Observatory on their first date.

We’re now into the Development section, with Mia working on her one-woman show and Sebastian touring with his friend’s combo. The summer montage sequences offer other numbers, including Sebastian’s performance with the jazz group and the “City of Stars” duet with the couple at the piano. These bits don’t fit easily into Veirtel’s template, but what does is the “curtain song,” the Messengers’ “Start a Fire” number. It’s splashily performed at the concert that makes Mia apprehensive.

The performance functions as a curtain song, I think, because of Viertel’s claim that the close of the first act typically signals dashed hopes. The curtain numbers of Gypsy, Guys and Dolls, Carousel, West Side Story, and other shows announce a failure to achieve goals. “The most typical kind of first act curtain,” Viertel explains, is “the unraveling, in an instant, of everything everyone has planned.” It’s too strong a description of La La Land’s concert, but Sebastian’s cynical keyboard tweaks during the band’s blast of adult contemporary R&B mark him as a sellout. “Do you like the music you play?” He seems to have given up his dream, a failure that becomes the first crack in the couple’s relationship.

There are fewer discrete numbers in the film’s last stretch; it lacks several songs in the Viertel template (the Welcome-Back number, the second star turn, more subplot songs, and the first big showpiece). Owen Glieberman has noted that the film’s second hour is notably less buoyant, and the first full-blown number in the Climax is melancholic.

“The Fools Who Dream” is gently confessional, in contrast to the overheated delivery of Mia’s earlier auditions. It’s what Viertel calls a second-act showpiece, and true to that convention it yields a big plot point: She wins the role.

The resolution of the plot, what Viertel calls the “next-to-last scene,” need not be a number at all. It’s often a “book scene,” and so it is here. After Mia wins the role, she and Sebastian admit both their love and the difficulty of staying together.

There follows the finale, a bookend to the freeway opening. “The 11:00 scene,” as Viertel points out, is often a wide-ranging reprise. La La Land’s eight-minute sequence presents a synthesis of the musical motifs and a revised, stylized version of Mia’s career.

Oklahoma! is usually credited with popularizing the fantasy ballet interlude, a convention that was picked up in the “Miss Turnstiles” daydream of On the Town, the Girl Hunt of The Band Wagon, and many other what-if sequences in Hollywood musicals. As a stroke of novelty, La La Land saves its fantasy ballet for the end, and makes it a bittersweet contrast to the real resolution.

Reports on the creative process behind La La Land indicate that the filmmakers were constantly weighing their choices about where to put their musical interludes. The fact that they settled on a layout that sticks fairly closely to the Broadway template suggests that Viertel’s song plot has advantages that creators intuitively gravitate towards. Its emotional arc both complements and extends the drama-driven plot.

The long and the short of it

Viertel’s anatomy of the Broadway song plot nicely fills out some patches of classical dramaturgy. It helps us better understand the tacit guidelines that creators follow, and it shows how even movies not drawn from stage shows have absorbed some of their conventions. Yet Viertel’s layout does more than point up the affinities between La La Land and stage musicals. It also helps us see where the film rejects the traditional schema.

The film’s deletions from the song plot omit love triangles (of any consequence), subplots, villains, and parallel couples. Sebastian’s sister is basically an expositional device, while Mia’s roommates are barely characterized and her parents barely seen. The bandleader Keith is mostly a mouthpiece for a musical idiom, and the other members of the combo aren’t individualized. No secondary character is granted a show-stopper like “Sit Down, You’re Rocking the Boat” or “Steam Heat” or “Make ‘Em Laugh.”

In sacrificing subplots and side bits, La La Land forfeits what such devices add: a different range of emotions, thematic contrasts, relief from overexposure of the two lovers, and comic relief. The film gives up accessory pleasures, like the counterpoint romance of Nathan Detroit and Adelaide in Guys and Dolls, or the ballad of the parents at the piano in Meet Me in St. Louis. In a bold genre change, La La Land stands or falls by its two principals.

Strangely, this spare plot consumes two full hours. Compare its Hollywood counterparts. Cover Girl, another showbiz tale, runs fifteen minutes shorter, but has time for a fully-rendered sidekick, a competitor for the heroine Rusty, a nice role for Eve Arden, and a parallel plot (thanks to flashbacks) devoted to Rusty’s grandmother. At 95 minutes, On the Town squeezes in three couples and a New York travelogue. As for the often-invoked Demy, compare the 90-minute Umbrellas of Cherbourg, which manages to deck the plot out with two old ladies and two deftly characterized rivals for the central couple. Better yet, recall Les Demoiselles de Rochefort. Granted, it too runs two hours, but it has to pack in five couples, one triangle, a starstruck café waitress, and for good measure a serial killer.

More broadly, La La Land doesn’t give its protagonists sharply defined goals. They just want to succeed, through rounds of auditions or short-term music gigs. In Cover Girl Rusty is given clear-cut options: To sign on as a model or stay a club dancer? To marry a piano player or a Broadway impresario? And as Viertel points out, there’s often a bigger issue at play—statehood in Oklahoma!, modernizing a country in The King and I, moving a family from St. Louis to New York. Nothing like this hovers over the couple in this rather hermetic movie.

What fills up that extra running time in La La Land? For one thing, the very parallels that I’ve mentioned, notably the extended scenes in the café; but also, I think, the pool party, with its sideswipes at the movie industry, and the planetarium dance, pretty as it is. A older studio-era film would have gotten the romance going sooner, in the Setup, sharpened the choices facing the characters, and fleshed out their milieu with friends, family, and minor players who get a little bit of the spotlight. (Keith would almost certainly have gained a romantic partner, hopefully a wise-cracker.) A Demy film would have added more characters as well, with a crisp geometry of counterparts and substitutions. Everything would be color-coded too.

The slimness of the plot can be taken as a point against the film, but focusing a musical so tightly on the couple was probably worth trying. If anybody cares, I enjoyed the film, and—to invoke the distinction between taste and judgment—I think it’s a solid, sometimes stirring effort. But what matters to me now is the way that thinking about craft traditions, particularly as they affect structure, allows us to plot some ways in which La La Land is both traditional and original. Evaluation is important, but it can be guided by analysis. An essential part of criticism involves studying how things are made.

Thanks to Jeff Smith for advice about the Messengers’ musical idiom, and to Michael Campi and Peter Rist for discussions about the film.

The quotation from Shklovsky at the start comes from the extract from A Sentimental Journey (1923) in Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader, ed. and trans. Alexandra Berlina (Bloomsbury, 2017), 150. For another Shklovskyan foray into contemporary moviemaking, you can try “Pulverizing Plots.” My quotation from Viertel on first-act curtains comes from The Secret Life of the American Musical, p. 152.

More on the making: A fairly detailed account of LLL‘s choreography is provided at the Verge, with more film references than you can shake a stick at. On the authenticity dimension, Glenn Kenny gets on the case of jazz purists.

Kristin’s discussion of four-part structure is at its fullest in Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Analyzing Classic Narrative Structure. I discuss it and apply it to some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Msodern Movies. For more examples, visit our category Narrative Strategies.

P.S. 24 January 2017: LLL has garnered a heap of Oscar nominations this morning. Now this Los Angeles Times story supplies more information on how it was made (financially).

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967).

My girl Friday, and his, and yours

DB here:

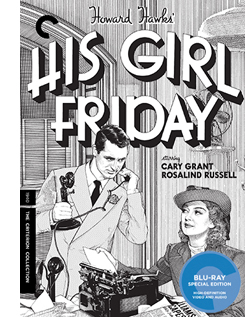

Criterion has just released a fine edition showcasing two classics of American cinema: The Front Page (1930) and His Girl Friday (1940). His Girl Friday is in a new HD restoration, and the earlier film, long crawling around in disgraceful public-domain bootlegs, now has a 4K glow–maybe looking better than it did at the time. The extra fillip is that it’s a version that director Lewis Milestone preferred to the familiar one.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Needless to say, I’d be plugging this release strenuously even if I weren’t involved. Long-time readers of this blog know that an early entry hereabouts talked about the diverse paths HGF took to becoming the classic it’s now recognized to be. I used the film in many courses I taught during my early days at Madison. Kristin and I have been writing about the film since then as well, first in Film Art (it still retains its place from the 1979 edition), then in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1998). Other references sneak into our entries here from time to time. The Criterion edition offered me another chance to rattle on about a movie I still, after nearly fifty years, love inordinately.

What can be left to say? Plenty, but today I’ll mention just two items. First, what is a Girl Friday? And second, how unobtrusively delicate can film style be?

More slop on the hanging

The phrase “girl Friday” comes, ultimately, from Robinson Crusoe, Defoe’s 1719 novel of how the castaway protagonist turned a cannibal prisoner into his servant: his man, Friday. The hapless convert to Christianity gained his name because Crusoe rescued him on a Friday. An 1867 children’s story, “Will Crusoe and His Girl Friday,” shows a little boy and girl planning to reenact Defoe’s tale, adding gender insult to racial and class injury.

“My Girl Friday” was a spicy 1929 play about flappers who drug tycoons at a party and then convince them that the worst has happened. Consisting largely of scenes with chorus girls in bathing suits, it was dubbed by Variety “out and out smut.” Unsurprisingly, it found success on Broadway. During some weeks its BO take rivaled that of The Front Page, on stage at the same time.

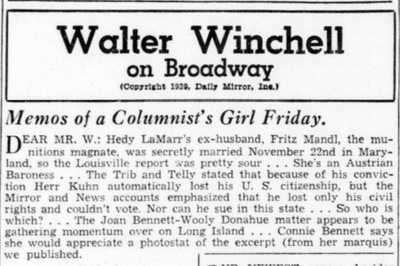

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

He started a brief feud when he smelled poaching. In 1937, two aspiring screenwriters sold MGM a story they called “My Girl Friday.” It involved, according to Daily Variety, “adventures of a newspaper circulation rustler.”

With Trumpian self-regard, Winchell asserted that he had popularized many catchphrases that Hollywood had bought as titles: “Blessed Event,” “Orchids to You,” “Is My Face Red?” “Okay, America,” and even “Whoopee.” In addition, he noted that MGM had spent a cool quarter of a million dollars to enhance a scene of The Great Ziegfeld. In the face of such largesse, Winchell felt justified in asking for compensation.

Therefore we think it would be ducky if MGM sent $10,000 to us for the use of “My Girl Friday,” which became better known via this dep’t.

Winchell hastened to add that he would give the money to charity. He pressed his case in several columns and in radio broadcasts. Paramount joined the fray, claiming that it acquired the title when it bought the old play, so MGM couldn’t use it anyway. At which point the Hays Office was consulted.

Using his Girl Friday voice, Winchell responded that he claimed only to have popularized the phrase, and in any case what was $10,000 to Hollywood, especially if the money went to charity? Muttering about how MGM’s song “Your Broadway and Mine” swiped the original title of his column, Winchell subsided, as did the dispute. MGM evidently never adapted the story in question.

Then, on 9 December 1939, Walter ran this.

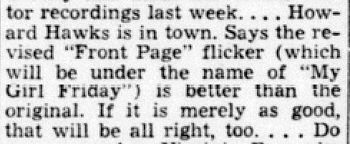

No hard feelings from Winchell, apparently. He may have benefited from the association with the movie. During production and even after release, the film was sometimes called My Girl Friday. And the linkage of a Girl Friday to the newspaper game, be it gossip or circulation rustling, fitted the movie well, as it evoked Winchell’s rat-a-tat radio delivery and his near-prosthetic adhesion to phone receivers.

Yet Winchell mysteriously dropped the “Memos” rubric from his column in 1941. In the decades to come, many businessmen would claim to have a Girl Friday of their own. Maybe the film ultimately popularized the phrase more successfully than Winchell did.

For the waiter

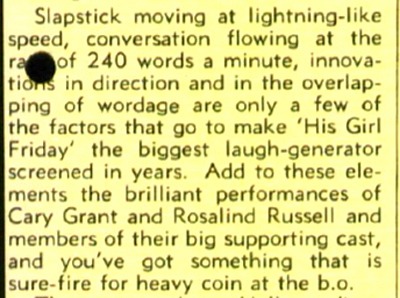

Daily Variety (5 January 1940), 3.

As a theatrical adaptation, His Girl Friday offers a challenge that Hawks accepted with ease. He had worked on films limited to a few interiors before, as with the train scenes of Twentieth Century (1934) and much of the airport action of Only Angels Have Wings (1939). He knew how to enliven situations unfolding in tightly confined settings.

Apart from enjoying the fast-paced comedy, you can learn a lot about film technique from the way Hawks energizes his static, prosaic surroundings. Take his resolutely unflashy staging in depth. It’s most apparent in the pressroom of the Criminal Courts Building, as I suggest in the supplement, but there are plenty of felicities of staging elsewhere. The most apparently unpromising example involves the restaurant where Walter Burns takes his ex-wife Hildy Johnson and her fiancé Bruce Baldwin. What to do with this simple set?

At a late point in the scene Walter will seek the help of the waiter Gus, who’ll call Walter to the phone. It’s a basic problem: How should the director prepare for that phase of the action? Hawks does it by setting up a zone of depth at the start of the scene, priming it quietly throughout, and paying it off when it’s needed.

Bruce, Walter, and Hildy enter the restaurant from the background. (Novice directors please note: No need for a sign saying, “Restaurant.”) The group comes to a table in the foreground. After some comic byplay as Walter grabs the chair next to Hildy, the three get seated and chat with Gus.

This framing orients us to the table and the rear area by the bar. We’ll never leave this general orientation on the scene. This commitment, far from being simply “theatrical,” makes for economy as the action develops.

In the course of the scene, Hawks activates the rear zone by having Gus come and go from it. Of course that area isn’t emphasized. Who’s likely to notice Gus giving the sandwich order back there when there’s patter and funny business to watch right in front of us?

In the course of the scene, Gus will come back to the table, pouring water, delivering sandwiches, and getting kicked in the shin by Hildy, who’s aiming at Walter. Throughout, we’re quietly primed for that alley of space behind Walter to be occupied by Gus.

The priming pays off when Walter, realizing that he has to prevent Hildy’s taking the train today, deliberately spills water in his lap.

Walter pivots and heads to Gus, who’s back there in his domain, waiting to be pulled into the plot. He’ll summon Walter to the fake phone call.

No big deal–certainly not as eye-catching as the dazzling comedy around the table. But the care for such little things is the mark of a craftsmanship that uses space compactly, without fuss. No need for camera angles that show the fourth wall (or even walls two and three). No need to build more of the set on the side; this is Columbia, after all. Just let reliable Joe Walker light that background enough to keep us aware of it (out of focus for most of the scene) and then activate it when you need it.

Hawks was obeying the advice Alexander MacKendrick would later give:

Within the same frame, the director can organize the action so that preparation for what will happen next is seen in the background of what is happening now.

Or as Hawks put it in 1976:

You know which way the men are going to come in, and then you experiment and see where you’re going to have Wayne sitting at a table, and then you see where the girl sits, and then in a few minutes you’ve got it all worked out, and it’s perfectly simple, as far as I am concerned.

The unstated premise is indeed perfectly simple: You don’t need to show more space than the physical action requires. It’s a rare premise today.

How long is it?

This sort of priming fits neatly into a cinema based in continuity–dramatic, spatial, temporal. Hawks is a master of staging action so that it flows unobtrusively. At times, though, it’s fun to spot some discontinuities, and editing is a good place to look.

Ozu is, to my knowledge, the only director who invariably creates perfect match-cuts on action. Even Hawks has to cheat things a bit to make the editing flow. (Hildy’s pitching of her purse is an example I use in the commentary.) But consider how Hawks can get a spark out of a small, mismatched action.

We’re still in the restaurant, and Walter has persuaded Hildy to cover the Earl Williams story in exchange for buying an insurance policy from Bruce. Talking of his upcoming physical, Walter boasts, “Say, I’m as good as I ever was.” Hildy fires back, “That was never anything to brag about,” and Walter reacts and turns his head. As he turns, we get these two shots.

At first Walter is stunned, apparently readying a reply; but at the cut, he’s sporting a grin. It’s partly a grin of triumph, showing that he’s gotten Hildy to do his bidding, but it’s also an appreciation of her wit: a sort of “That’s my girl” pride in her fast comeback. Strictly speaking, the cut’s a mismatch, but the instantaneous switch in reaction gives the scene double value.

Finally, there’s framing. The rugged outdoor guy Hawks is as delicate as they come when it’s a matter of frame corners and edges, and his sense of pictorial balance is fastidious. Go back to the long opening scene in Walter’s office, when he and Hildy are going through the preliminaries. They size each other up before Walter sits down in his swivel chair.

A slight track forward has planted Walter in the lower corner of the frame. A cut in to Hildy’s reaction (not shown) enables a transition to a slightly different framing. That setup allows Walter to invite her onto his knee, which pokes up from the bottom edge.

Joe Walker has obligingly edge-lit that stretch of pant leg, and it’s about the only thing moving in the shot, so we can’t miss Walter’s come-on.

Now Hawks does something very pretty. Hildy moves to the table and perches on it. Hawks reframes with her, but keeps the shot oddly unbalanced, with Walter resolutely facing the area she’s not in.

A sort of spatial suspense develops. Hawks sustains this odd framing while Walter picks up a cigarette, tosses one to Hildy, lights up, and tosses her a match. Fairly deliberately too, in what’s supposed to be Hollywood’s fastest movie.

When both are smoking comfortably, Walter swivels his chair to snap his head into the lower left corner, which has been waiting for him all along. The simple movement provides the scene’s new beat, which starts with Walter’s line: “How long is it?” I haven’t yet mentioned that this is a fairly dirty movie, but you knew that.

The shot began with the actor’s head in the lower right, developed with that head poised midway in the frame, and now ends with the head cocked in the lower left. What looks like sterile geometry feels, on the screen, perfectly unforced. And lest we misread the “How long is it?” Walter innocently explains, in a medium shot, that he’s just wondering how long it’s been since they’ve seen each other. That in turn calls up an over-the-shoulder reverse angle, and the next phase of the scene is off and running.

At this point in film history, the cinematographer, while shooting, could not see exactly what the lens was taking in. The careful unbalancing and rebalancing of the shot had to be achieved through a mixture of expertise and intuition. The same thing with keeping Gus in reserve back there by the bar, and letting an incompatible take of Grant’s reaction stay in after a cut. It’s all perfectly simple, as far as I’m concerned.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and Peter Becker of Criterion for inviting me to spend more time with this splendid movie. Hawks’ quotation about keeping it simple comes from my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), 149.

You can find background here on the restoration of The Front Page, supplied by Academy archivists Mike Pogorzelski and Heather Linville.

You can get a sampling of Winchell’s radio delivery from the period here, complete with nervous teletype clackings serving as transitions. For more background on HGF, go here. That entry observes the usefulness of the film’s lines in many situations. In this respect it resembles another Hawks film, that repository of worldly wisdom known as Rio Bravo.

Gus the waiter is played by the inimitable Irving Bacon, one of a dozen or so outstanding supporting players. This is another of the film’s triumphs: Regis Toomey, Porter Hall, Gene Lockhart, Abner Biberman, Roscoe Karns, and other memorable character actors all seem to be having fun. And Billy Gilbert as the wayward Pettibone is the friendliest deus ex machina in Hollywood cinema.

Finally, do audiences today know the meaning of Hildy’s flipped hand in response to one of Walter’s catty remarks? Has nose-thumbing gone out of popular culture? Apparently not.

P.S. 4 February 2017: On the Parallax View site, Sean Axmaker has the most in-depth appreciation of this edition of The Front Page I’ve seen online. And he has plenty to say about HGF too.

P.S. 2 February 2018: His Girl Friday is now streaming on FilmStruck, and among the bonus materials is the video essay I mention.

His Girl Friday (1940).

Fantasy, flashbacks, and what-ifs: 2016 pays off the past

La La Land.

DB here:

After I see a new movie, I like thinking about its ties to film history. This isn’t a matter of sneering, “They did it better in the old days,” though often that’s true. Rather, I like exploring how our films both rely on and swerve from the traditions they invoke.

I’m not talking only about movies that self-consciously point at Hollywood’s past, as La La Land does. Every new release participates in film history—and sometimes changes it. Most critics don’t have the space or inclination to point this up, but those of us who study film as an art can. Looking closely at form and style makes the past present to us in a vivid way.

Students are taught that in the 1910s Griffith took crosscutting to a new level, and true enough. But it’s not often mentioned that crosscutting has remained a permanent expressive option for filmmakers today. Very often they use it as Griffith did: to build tension, especially in a chase or a race against time; or to highlight narrative parallels, as he did in Intolerance. What excites young audiences in the work of Christopher Nolan, for example, are in large measure smart elaborations on principles that go back a hundred years.

This isn’t to complain that Nolan isn’t original—originality in the strong sense is very rare—but rather to point up an overarching dynamic of continuity and change across the history of the art. We understand what Nolan’s doing better when we see how he recasts inherited techniques, as when Inception takes parallel crosscutting to a kind of limit in its embedded dreams.

My upcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, is an effort to refine an argument I made in The Way Hollywood Tells It: that major narrative techniques of contemporary cinema got consolidated in the 1940s. The techniques I have in mind include general principles like non-chronological plotting and subjective probing of character’s experience, as well as particular devices like flashbacks, voice-over, and fantasy scenes.

I say “consolidated” because many of those strategies can be found sporadically in the silent era and the 1930s. Forties writers and directors adapted them to the sound cinema, made them popular, and explored them in ways that go beyond most earlier instances. These filmmakers added a body of resources to the classical tradition: after the 1940s, later filmmakers could develop the techniques in fresh ways. There were new colors on their palettes.

I talk about several films, and among those I significantly spoil The Shallows, Manchester by the Sea, The Birth of a Nation, Nocturnal Animals, Moonlight, and La La Land. But you should be able to skip the films you fear I’ve overshared on.

Schemas and their sneaky ways

Reinventing Hollywood argues that we can understand the process as one of schema and revision. I borrow from E. H. Gombrich the idea that a schema is a pattern handed down by earlier artists that becomes a point of departure for those who follow.

For example, shot/reverse-shot cutting is a stylistic schema, going back to the 1910s. Every professional filmmaker knows how to execute it, though some will find fresh ways to use it. The Shallows, a summertime thriller from the talented director Jaume Collet-Serra, uses it in orthodox ways throughout.

Most filmmakers apply the shot/reverse-shot schema to phone conversations as well. But here Collet-Serra innovates (mildly) by using cellphone technology to give us a phone conversation with a redoubled shot/reverse-shot pattern. The editing schema is given within a single frame as Nancy talks with her father.

This isn’t, I think, a mere gimmick. For one thing, we’re primed for it by the scene of Nancy’s arrival, when she browses through photos of her dead mother. Those are delivered to us as paste-ups in the same frame, rather than as optical POV shots of Nancy’s phone. Soon after, still during her ride to the beach, we see an instant message from her friend.

So the pseudo-shot/reverse-shot has been prepared for by these other displays of her screen. We’re ready for this to be an intrinsic norm of this film. Later we’ll get the ticking-clock deadlines through inserts of of her watch.

More generally, the film as a whole tightly restricts us to Nancy’s experience. Nearly everything we see and hear is filtered through her consciousness. (The film’s momentary detours from her range of knowledge work to maximize suspense, in the manner of the bomb under the table.) During the phone conversation, cutting back to her father at home in Galveston would have made him a more important character. As it is, the narration keeps the emphasis on her situation and the beautiful but menacing landscape, the “perfect beach” that she needs to conquer as her mother did.

Shot/reverse-shot is a schema for handling stylistic options. I suggest that there are narrative schemas too, tried-and-true storytelling patterns that filmmakers can repeat, reject, or revise. Novelty builds on familiarity. As Damien Chazelle describes La La Land: “I’m trying to hark back to certain old traditions but hopefully show you something you haven’t seen before.”

For the viewer, schemas supply a certain predictability. We’re used to the back-and-forth of shot/reverse-shot cutting. Likewise, we expect a flashback to supply background information that clarifies the situation in the present. In the American studio tradition, a filmmaker who revises a schema needs to give us enough of the pattern to make us realize the alterations. The Shallows‘ revision of shot/reverse-shot is clear to us because, given our knowledge of FaceTime/Skype technology, we can grasp the images as diagrammatic presentations of a familiar editing pattern. Similarly, we can sense a flashback even when it’s quick or cryptic, and we anticipate that things will clarify later. The dynamic of familiarity and novelty will work only if the the new twist plays off something recognizable.

Back in September, I noted that almost every film I was seeing seemed indebted to 1940s storytelling, but I talked only about Sully. Today I go wider and look at several 2016 films, both pop and prestigious, that rely on methods of roundabout storytelling that coalesced back then. We’re so used to these methods that we tend to forget their debts. By analyzing how our writers and directors draw on this tradition, we better understand their roots in film history–and their genuine contributions to changing it.

In her, and his, shoes

One of the most taken-for-granted narrative strategies is that of subjectivity. Here filmmakers use images and sounds to reveal a character’s mind and senses. The main schemas have become very familiar.

Today we scarcely notice optical POV shots or fantasy imagery. They were common in silent film, became less common in Hollywood in the 1930s, and grew very common in the 1940s. The sustained optical POV of Lady in the Lake (1947) is one instance, and so are the protracted dream and delirium sequences in psychological films like Spellbound (1945) and The Lost Weekend (1945).

Go back to The Shallows and you’ll find plenty of POV shots. When Nancy regains consciousness after the climax, we get a mixture of optical viewpoint and imaginary shots, when she first sees Carlos and then “sees” her mother’s approval of her courage.

Dreams are another common device for rendering subjectivity. They became commonplace in the psychoanalytical films of the 1940s, and have been used ever since to probe the more or less unconscious impulses of our characters. We’re let in on characters’ dreams in A Quiet Passion, Hacksaw Ridge, and Kubo and the Two Strings.

Both visions and dreams become important motifs in The Birth of a Nation. Early in the film, the child Nat Turner, who has been called “a leader and a prophet” by an elder slave, dreams of himself in tribal paint running through a forest. Later, grown-up and developing a sense of himself as a rebel against oppression, he re-experiences the dream, only now the child encounters himself as an adult, who moves to protect him. The child becomes father to the man.

These plunges into subjectivity run along with images of Nat’s revelation: an angel he sees at moments of greatest torment, on the whipping block and on the gallows.

On the second occasion, the figure is more fully revealed as an angel, and she seems ready to embrace him. The nocturnal spirituality of the opening has been counterbalanced by something like Christianity, but it’s hardly the white folks’ version: Nat sees a dark angel.

Frames and breaking frames

Moana.

Subjectivity can also shape our sense of time, thanks to flashbacks. Very common nowadays is the brief flashback representing a sudden memory. In Allied, a shot of Max and Marianne on their rooftop bed-sit in Casablanca comes when Max is recalling their mission, after he’s learned she might be a German spy. A parallel device is the auditory flashback, as when a character recalls earlier lines of dialogue, which might not be accompanied by imagery from the past scene. Several of these films drop in sonic flashbacks, which serve as reminders to the audience as well as recollections for the characters.

A subjective push into the past can take over the whole structure of the film. This happens when big stretches of the plot are presented through flashbacks to events that characters tell or remember. A fairly pure case is Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. It intercuts three time periods: the present, as Billy and his comrades in arms visit a Thanksgiving football game; Billy’s return to his family two days before the game; and the more distant events of Billy’s tour of duty in Iraq, culminating in the death of his beloved sergeant Shroom.

Throughout the film we’re largely restricted to what Billy experienced in both present and past.

In most films, though, flashbacks don’t represent memories. Often a flashback is initiated as a character’s recollection or testimony, but it presents events that a character didn’t know about. In these cases, the film has it both ways–subjective when it wants us to feel with the character, but wider-ranging when the extra information can yield suspense or another perspective on what the character knows. This happens in Jackie, in which Jacqueline Kennedy tells a journalist about the JFK assassination and its aftermath. We mostly adhere to what she could have seen and heard, but some incidents occur outside her ken. The interview situation motivates the return to the past, and that’s usually what we find in these partly subjective flashbacks.

The flashback technique was fairly common in Hollywood’s silent era but rarer in the 1930s. It emerged as a major creative option in the Forties; there are more flashbacks in 1944 feature releases than in all of the Thirties. Nowadays most films, even Moana, resort to it. (Maui’s boasting song “You’re Welcome” reviews his gifts to humanity.) Virtually every film I mention today employs at least one flashback–a testimony to the enduring power of this storytelling norm.

Since even the most personal flashbacks tend to stray from what characters could have witnessed, it’s not surprising that today we commonly have completely “objective” flashbacks. The plot simply jumps to and fro through time without the alibi of character memory. Hollywood has occasional early instances (Beau Geste, 1927; A Man to Remember, 1938; Confidence Girl, 1952; The Killers, 1955), but the “external” flashback is rare before the 1960s. Over the decades, filmmakers and audiences became comfortable with the flashback that simply admits itself as such. The time shift may be signaled by a title (“Two Days Earlier” in Billy Lynn), but some films find other ways to announce the flashback.

A simple example is Ben-Hur. Steered by a voice-over narrator (who will turn out to be a character in the film), the opening shows the start of a chariot race in a Roman Circus. Two young bravos swap lines that arouse curiosity: “You should have stayed away.” “You should’ve killed me.” “I will.” Then the race starts, the camera pans left to follow it, and the shot dissolves (a graphic match) to an image of two horsemen racing around a rock.

They are youthful versions of the competitors we’ve just met, and we’ll learn that Messala is Judah Ben-Hur’s adopted brother. The rest of the plot follows the friends’ careers that lead them to the fateful chariot competition. And that opening stretch is replayed when the flashback catches up with the frame situation. We’re reintroduced to the Circus, and identical shots show them exchanging the same lines we heard at the start.

This sort of overlapping return to the frame is common when the flashback consumes a large chunk of the film. One traditional schema, used in Ben-Hur, presents the frame story as a situation in crisis. This serves to grab our attention, to raise questions, and to hold the outcome of present-time events in suspension while the backstory clicks in.

The crisis structure is seen in Hacksaw Ridge, when after glimpses of a ferocious battle we see the protagonist rushed along on a stretcher. Thanks to a title, “Seven Years Earlier,” we shift to the past in another “objective” flashback. Eventually we’ll loop back to the wounding and rescue of Doss at Hacksaw Ridge.

The earlier versions of Ben-Hur didn’t resort to flashback construction. Similarly, Sergeant York (1941), which has similarities to Hacksaw Ridge, relies on straightforward chronology. The crisis schema became popular in the 1940s (e.g., The Big Clock, 1947), but it’s even more common now than it was then.

So is a willingness to put flashbacks inside flashbacks. Hacksaw Ridge‘s main flashback breaks its own chronology to show scenes of domestic violence in Doss’s youth. The main flashback of Ben-Hur plays host to embedded flashbacks too. The large-scale Chinese-box construction of 1940s films like The Locket (1946) and Passage to Marseille (1944) is still uncommon, but brief flashbacks wedged inside a long-term one pose no problems for current audiences.

Ben-Hur and Hacksaw Ridge set up the Now situation straightforwardly and at some length. At the opposite extreme is the present-time opening of Don’t Breathe: a slow swoop down to a barren street along which a man drags a young woman’s body. A second shot isn’t very informative about him or her, and the two shots consume only 63 seconds.

Probably most viewers forget about this cryptic but intriguing crisis situation until it’s repeated at the climax–the shots in reverse order, the woman more clearly visible, and the two shots clipped to a mere nine seconds. This is compact storytelling.

The Shallows sets up its Now through attachment to a minor character. A little boy finds a video camera on a helmet floating in the surf. He plays the footage and, seeing a shark attack recorded there, runs to get help.

Later the boy’s discovery is shown again, and now we’re in a position to appreciate its importance. But like the opening sequence of Mildred Pierce, this prologue has omitted key information: the boy’s replay of Nancy’s recorded plea for help. At the climax that footage, which we’ve seen her make, is is now re-run for us as the boy watches it. Again the boy is shown running for help. This overlap brings us up to the original Now.

At the start there was an enigmatic rack-focus to the buoy in the distance. In the replay, while the boy studies the video, we see Nancy bobbing there, waiting for the shark to attack.

This scene, incidentally, shows how a flashback structure can take the sting out of a convenient coincidence. If something unlikely–the boy discovering the camera in time to help the heroine–is shown before the main action, then it doesn’t seem as out-of-nowhere as it would if presented in straight chronology. After seeing the somewhat cryptic opening, we might even be looking forward to the revelation, as presumably some viewers are when a scene in the flashback introduces the surfer with the camera helmet.

Interestingly, neither Don’t Breathe nor The Shallows resorts to a title announcing the transition from Now to the past. Can it be that our genre pictures can live with a little less redundancy than our Oscar bait?

Strands, mosaics

Jackie.

Filmmakers never tire of tweaking flashback conventions. A more subdued variant of the crisis setup is used in Manchester by the Sea. Joe Chandler dies and his brother Lee, working as a maintenance man in Boston, is summoned back home to Manchester. These scenes alternate with episodes from the past, out of order, showing the brothers’ relationship and Joe’s eventual death. The crisis comes about fifty minutes into the plot, when in a lawyer’s office Lee learns that Joe wanted him to take custody of his son Patrick and move back to Manchester.

Lee’s resistance to this plan is explained in another string of flashbacks that show the disintegration of Lee’s marriage, the death of his children, and his attempted suicide. He has left the town behind and lives in self-inflicted pain and isolation.

At this point, the film reverts to chronology in the Now. The drama pivots around Lee forging a relationship with Patrick and coming to terms with his past. Only two brief flashbacks break up the story line, and those relate to Joe’s disappointment at Lee’s retreat from the world into a menial job. If the first half had been presented chronologically, we would have lost the sharp contrast between Lee’s scowling reluctance to reach out to Patrick and the more vigorous, emotionally open man he once was. Hollywood films may not excel at portraying gradual character change, but flashbacks allow a sharp sense of Before and After that can suggest how humans remake themselves in response to events.

The mosaic quality of the flashbacks dotting Manchester by the Sea can be seen to a lesser extent in Jackie. Here there are four principal strands of time to be interwoven, with glimpses of others. One strand involves the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath–the public ceremony of the display of his body and his burial in Arlington. Another involves Jackie’s consultation with a priest some time after JFK’s death, discussing her plans to bury their first two children, who died as babies, alongside him. A third strand, temporally pre-assassination, presents her famous 1962 tour of the White House. Finally there’s her post-assassination interview with a reporter who asks her questions about her role as First Lady and her handling of the horrific Dallas tragedy. We also get glimpses of the 1960 inauguration ball and Pablo Casals’ 1961 concert at the White House.

The film opens with the reporter calling on Jackie and the two settling down for their talk. He’s a bit provocative and probing, she’s guarded and self-censoring. The somewhat odd angle of the shot/reverse-shot framings, with her eyeline only a little off-center and sometimes straight at the camera, conveys an eerie ceremonial stiffness.

The reporter’s interview seems to be the frame for the flashbacks. Not only does their meeting occupy the normal position of a framing situation, but we’re aware that another schema triggering flashbacks is a testimony situation. In court, in a police station, at home quizzed by a reporter: These often set up a flashback narrative. The probing-reporter schema was crystallized in the 1940s with, of course, Citizen Kane (1941) but also with earlier films like The Escape (1939), Edison the Man (1940), and The Great Man’s Lady (1941).

Snowden is a good contemporary example of the reporter-interview frame. Long blocks of flashbacks are enclosed within a ticking-clock situation in the present. Snowden retells his life, in chronological order, for Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald.

The film’s narration is largely tied to his range of knowledge during those periods, especially when suspense is at stake. We get plunges into subjectivity when he’s struck by epilepsy, and much optical POV cutting, notably when he downloads the NSA files as officials mill around outside his cubicle. As often happens in classical filmmaking, the narration widens its perspective to provide montages of news reports and reactions to Snowden’s revelations by his associates around the world.

Snowden tidily frames its past episodes by the present-time action before and after the big interview. The final scenes, and the credits, show the consequences of his whistle-blowing in the days and years afterward. But Jackie revises the testimony schema in an unusual way.

As the film goes on, it’s revealed that the reporter’s interview with Jackie isn’t the ultimate Now. The last events in the story chronology are Jackie’s consultation with the priest and the burial of her children. But from about 45 minutes onward, the priest’s attempts to console her are intercut with the interview. They are, in other words, flash-forwards.

They’re initially concealed as such because they follow Bobby Kennedy’s suggestion, in the assassination’s aftermath, that Jackie talk to a priest. That cue inclines us to assume that the priest’s advice is given during her final days in the White House. Only when the reporter phones his editor and says Jackie intends to bury the children beside Jack, and when Jackie tells the priest that the reporter’s story went around the world, are we aware of the burial scene’s place at the very end of story chronology.

This is a cogent example of schema revision: a frame that doesn’t enclose everything that, by convention, it should. One effect is to make the burial of the children an unexpected climax–a revelation of how much death this woman has seen, and a counterpoint to the glittering image of “Camelot” on which the film closes.

So where you put your flashbacks turns out to be crucial. Had the flashbacks to Lee’s tragic mistakes in Manchester come earlier, we’d probably be less sympathetic to him than we are; by the time of their arrival, we’ve seen his long-term suffering and are prepared to have a complex judgment of him. The timing of flashbacks also shows to good effect in Nocturnal Animals.

Most of Nocturnal Animals is dominated by another device for braking chronology: the embedded story. Here a plot involving new characters is wedged within the main story. Novels have done this for some time, as when a character discovers a manuscript that opens a story world containing a completely new cast. In the comic book Watchmen, the story Marooned is read by a minor character in the main plot.

In films of any period, such discrete embedded tales are rare. In the 1940s, the chief variant involves dream plots: the protagonist falls asleep and the dream consumes the bulk of the film, as a long flashback might. The main character might retain her identity, as Dorothy does in The Wizard of Oz (1939), or the dream character might be a new persona, as in Du Barry Was a Lady (1943), where Red Skelton becomes King Louis XV. Either way, an alien story world is opened up.

Nocturnal Animals contains an elaborate embedded story. Art-gallery owner Susan Morrow is in the dumps; her chi-chi friends are cold and her husband is having an affair. She receives the manuscript of a novel from her first husband Edward. Over some days Susan reads this harrowing pulp exercise set in west Texas, and it’s dramatized for us in chunks. interspersed with her daily routines.

At first we might think that the novelistic sections are “objective” presentations of the scenes, a parallel fictional world. But about 45 minutes into the film, we get a flashback to Susan meeting Edward at the start of their romance. (Actually, it’s a re-meeting; they had crushes on each other years before.) Thereafter flashbacks to their courtship and their marriage are interspersed with more stretches of the novel. Tony, the hapless, somewhat spineless protagonist of the novel, is played by Jake Gyllenhaal, who also plays Edward.

The flashbacks invite us to find a dose of subjectivity here. Is Susan reading the novel as a portrayal, deliberate or unwitting, of Edward’s feelings of inadequacy in their marriage? She cheated on Edward with the man who became her second husband, so she may also be projecting her own guilt onto the terrifying fate of Tony’s wife–interestingly, not played by Amy Adams, the actress portraying Susan.

In Nocturnal Animals, the frame is neater than in Jackie; at the film’s end we return to Susan’s present life. But an ambiguous ending asks us to consider how fully we have entered into her imagination.

There’s a more drastic revision of the flashback schema, or rather the audience’s presuppositions about it, in Arrival, which I’ve talked about here. But interesting flashbacks with a 40s flavor are also at work in James Schamus’s Indignation, analyzed here.

Strands or blocks?

I think these examples show that it can be useful to think about film narrative from the standpoint of craft. Since the filmmakers made choices, what rationale justifies them choosing what we have rather than what we might have had?

For example, it would have been perfectly possible to arrange the time-layers of Jackie or Manchester by the Sea as blocks, separate chapters (perhaps given titles or dates) rather than as interwoven strands. Similarly, Nocturnal Animals could have shown us Susan’s marriage to Edward as one block, then her life with her second husband, and then the embedded novel as one long stretch. Thinking about how these alternatives would alter our experience can give us insight into the benefits and costs of the choices the filmmakers went with.

Block construction became a somewhat popular storytelling option in the 1940s. Long flashbacks balanced against one another can create blocks, as in Citizen Kane and A Letter to Three Wives (1948). Similar were “chaptered” films like Holiday Inn (1942) and Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) and the episode-based films Fantasia (1942), Tales of Manhattan (1942), Flesh and Fantasy (1943), and others. Welles, always alert to trends, planned such a structure for It’s All True.

2016 has given us two pure examples of block construction, both of considerable interest. The most visible one is Moonlight, which tells its character-centered story in three phases of the life of Chiron: his boyhood, his teenaged years, and his early adulthood.

The sections are announced by titles: Little, Chiron, and Black. The first two stretch over several weeks and show Chiron bullied by other kids and neglected by his crack-addicted mother. He also encounters helpers, at first the easygoing drug dealer Juan and his girlfriend, and later his schoolmate Kevin, who in the second episode is forced by the other boys to beat Chiron. The final episode unfolds in a single night. Chiron, now called Black and grown to be a powerful man, has become a drug dealer and is filmed somewhat parallel to Juan.

Black visits a diner where Kevin works. Tentatively their affection and sexual yearning for one another are rekindled.

As with any creative choice, there are trade-offs. Moonlight‘s sharply-edged episodes refuse a smooth arc of action; they sample his life and deny us a clear “coming of age” process. There are gaps between the stories, and the one between the second and the third episodes is crucial. We’re left to imagine what happened to Chiron that turned him into the muscled, tough Black. Perhaps the fight that got him sent out of school–the moment when he fought back at the main bully–marks his turning point. Surely too his prison experiences shaped his transformation, but we neither see those nor hear him tell about them. Director-screenwriter Barry Jenkins has left us to note the vivid change in character without supplying what Henry James called the “weak specification” of all the events that shaped him. Block construction has left empty spaces for our imagination to fill.

Another fairly pure case of block construction is Paterson. (I discuss it briefly here.) The plot consists of a week’s worth of events, broken into days starting on Monday. We follow Paterson the bus driver on his daily rounds of going to work, doing his driving, coming home to his wife, walking their dog, and sometimes paying a night visit to a local tavern. Some incidents are variants of others, such as the morning conversations with Donny, Paterson’s supervisor, or the glimpses of different sets of twins around town.

The daily blocks are marked, at least initially, by a title stating the day of the week, but this pattern is varied: No titles for the weekend. Another marker is the opening shot of each segment showing Paterson and his wife in bed from straight above them.

This image varies too, with different compositions and shot scales each morning, and in one case, Paterson alone. Cinematographer Frederick Elmes explains that each day changes:

So there’s a routine. He’s going to leave and return to the house at the same time every day, so it’s going to look the same. I said to Jim [Jarmusch, the director], “It might be nice to have some gentle differences between them, to define one day from the next.” That became our task, finding ways of keeping things visually interesting without going too far.

Today block construction often calls forth the sort of stylistic tagging pointed out by Elmes. The same differentiation of visual textures is found in flashbacks. A funny example occurs in Sausage Party, when Firewater explains how the Non-Perishables created the myth of humans as kindly gods. The framing situation in the present is given in chiaroscuro imagery with thick volumes and plausible (for a cartoon) depth. The flashback to humans’ slaughter of the groceries is rendered in a screeching, retro/headcomix style and an abstract space.

This style is maintained for the fantasy version that Firewater and his cronies concocted to keep the groceries from panicking. Then we return to the narrating frame.

Not gentle differences here: glaring ones, suitable to comic exaggeration.

Something in-between operates in several of the films I’m considering. In Café Society, two cinematographic styles differentiate between the major locales, Hollywood and New York. Jackie‘s post-asssassination flashbacks are filmed in a free-camera style distinctly different from the locked-down, planimetric shots of the interview and the more studio-bound images of the TV filming of the White House Tour.

Likewise, Nocturnal Animals assigns three different “looks” to its three levels. DP Seamus McGarvey explains that Susan’s present had to be “colorless, [with a] low-contrast anemic aspect to it.” The story within the story is “colorful, more primaries.” The flashbacks to Susan’s and Edward’s marriage have a softer, glowing texture.

Visually tagging blocks, fantasies, and flashbacks wasn’t uncommon in the silent era, when filmmakers marked them with vignettes and soft focus. These optical devices, along with distorting lenses, were occasionally used in the sound era too, along with occasional shifts between color and black-and-white (The Wizard of Oz; Portrait of Jennie, 1949). On the whole, differentiating strands or blocks became a firm craft convention somewhat later, from the 1980s on. I talk about how that happened in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Ooh-La-La Land

Believe it or not, I haven’t exhausted the debts of 2016 movies to Hollywood in the Forties. There is, for instance, the device of voice-over, so common in that decade, which reappears in various guises, most notably that of the gossipy narrator of Café Society. There’s also the strategy of confining the bulk of the film’s action to a single location, which became notable in Angels over Broadway (1940), Lifeboat (1944), Rope (1948), and The Time of Your Life (1948). That method, common to low-budget thrillers, was ingeniously exercised in 10 Cloverfield Lane, The Shallows, and Don’t Breathe. In another entry I’ve discussed how Sully uses the device of replay that became common in the 1940s.

La La Land sums up several of the tendencies I’ve mentioned. It displays block construction, with sections labeled Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter… Five Years Later. The film’s first section uses the flashback technique too. After we follow Mia out of the traffic jam and to the party and the piano bar, the narration jumps back to the traffic jam and tracks Sebastian through his day up to the moment he pounds out jazz at the piano. This brings them together. As she’s about to compliment him on his playing, he brushes past her and leaves. At about 25 minutes in, this is the turning point ending the film’s first part.

The rest of the film traces their other coincidental meetings until they fall in love, try to maintain their relationship, and ultimately break up. They re-meet at Sebastian’s club, with Mia now married to a courteous side of beef. As the two look at each other and Sebastian takes over the piano to play their love theme, the film skips back to the first piano-bar encounter. Instead of passing Mia, though, Sebastian grabs her and they kiss.

Now the narration posits an alternative story line in which they marry, become parents, and still have success. This what-if scenario is rendered in stylized settings, accompanied by moments of dance.

Like the visual tagging of blocks and flashbacks, this sequence needs to abstract its settings, theatricalizing them so they’re set off from the real-world locales in which our characters have also been singing and dancing.

La La Land revisits a schema that was explored a little in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood: the alternative-universe story line created by forking paths. I’ve talked about the clearest early example, the 1934 film adaptation of the play Dangerous Corner. It’s a Wonderful Life (1947) did it negatively: Imagine a universe without you (or George Bailey). A little-known instance from that period is Repeat Performance (1947), which offers its actress-heroine a narrative reset like that to come in Groundhog Day (1993), Run Lola Run (1998), Source Code (2011, talked about here), Edge of Tomorrow (2014), and many other media texts, including comics.

Again,the schema is creatively reworked. The past the couple might have had is played out with parallels to the real-world life that Mia found. The result is an epilogue balancing the traffic-jam prologue–these people, unlike the gridlocked drivers, have found their success in Show Biz–but at the cost of love. By showing us what might have been, the final sequence provides something both wistful and satisfying.

I regret missing certain films this year, particularly Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women, which seems to constitute an intriguing instance of block construction merged with a minimal network narrative. I look forward to catching up with it. And I’ve confined myself to Hollywood and off-Hollywood films, but I could easily have stretched the boundaries to include Elle (flashbacks), I Am Not Madame Bovary (block construction), Sieranevada (confined-space shooting, discussed by Kristin), Julieta (flashbacks, voice-over, etc.. etc., discussed in another entry), and many other imported films. These narrative strategies now belong to contemporary movie storytelling as a whole.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Thinking along these lines has made my 2016 moviegoing all the more fun. And a happy 2017 to you too.

E. H. Gombrich explains the concept of the schema throughout Art and Illusion, particularly in Chapter V and on pp. 313-314.

My quotation from Damien Chazelle comes from Mark Dillon, “City of Stars,” American Cinematographer 98, 1 (January 2017), 57. The same issue’s story “Quotidian Vision,” by Iain Marks, includes the remark from Frederick Elmes (p. 22). Seamus Garvey’s comments on the visual styles of Nocturnal Animals comes from Carolyn Giardina, “Beginning First in the Darkness, Then Moving toward the Light,” Hollywood Reporter, Awards no. 1 (December 2016), 48; apparently not available online. In the same article Vittorio Storaro talks about differentiating New York and Hollywood pictorially in Café Society.

The cellphone conversation in The Shallows is an interesting turn back to a much older schema for representing phone conversations, using split screen. The first one below is is from College Chums (1907). We’ve seen similar phone-call diagrams since then in Pillow Talk (1959), Bye Bye Birdie (1963), and Down with Love (2003, also below). Everything comes back eventually.

Other discussions of stylistic schemas hereabouts are in entries on lipdubs, shot/reverse-shot cutting, and Wes Anderson’s narrative worlds.

There’s another flashforward in these films: La La Land embeds a montage of the couple’s creative work in their “City of Stars” duet at the piano. Another, smallish block, it anticipates the looped construction of the final fantasy epilogue.

Snowden: Yet another revision of the shot-reverse shot schema, adapted for what John Dean called “telephonic communication.”