Archive for 2017

Time-shifting: THE PHANTOM CARRIAGE on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Today our comrades at the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck have posted Kristin’s new installment of our series, “Observations on Film Art.” It’s devoted to one of the most complex and intriguing of all silent films, Victor Sjöström’s Phantom Carriage (1921).

Sjöström was one of the greatest directors of the silent cinema. Although many of his films haven’t survived, we’re lucky to have several of his masterpieces, including Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, 1917), The Girl from Marshy Croft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), The Sons of Ingmar (1919), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). He mastered tableau staging in the early 1910s, then quickly learned the nuances of continuity editing, all the while drawing splendid, subtle performances from his actors.

The Phantom Carriage is a sort of horror fantasy. The premise is that the last person to die in a year becomes the escort for the dead of the following year. To this striking idea, taken from a novel by Selma Lagerlöf, the film adds an exceptionally intricate flashback structure.

Silent films made frequent use of flashbacks, usually brief ones to remind the audience of things seen earlier in the film, or longer ones that supplied backstory for the current situation. (In this respect, our films today are rather similar to silent movies.) The Phantom Carriage pushes farther, building its plot out of blocks of flashbacks that are presented out of chronological order, and not all representing memories. It was as daring in its time as The Power and the Glory (1933) and Citizen Kane (1941) were in theirs.

Because of its complexity, The Phantom Carriage long circulated in versions that were cut and rearranged. Once it was restored, we could appreciate just how ambitious a movie it was. Kristin traces the film’s various time schemes and shows that the shifts of chronology and point of view powerfully enrich a story of a man’s hard-won redemption. Her comments are enhanced by some excellent graphics from the keyboard wizards at Criterion.

As ever, we thank our Criterion collaborators: Kim Hendrickson, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, and their team.

A complete listing of our thirteen “Observations” entries is here. For more on Sjöström’s films, see our director tag.

Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight

Idle Wives (1916), produced by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley.

DB here:

This year I’ve been bouncing between two magnificently creative decades in US film, the 1910s and the 1940s. In autumn I’ve been caught up in things involving Reinventing Hollywood, but those were followed by some big doings on campus.

In spring I was lucky enough to be in residence at the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. That enabled me to watch nearly a hundred feature films from 1914-1918. I did a talk at the Library reporting on some of that work, and I’ve offered some preliminary observations on those in earlier entries.

Last week, Jim Healy of our UW Cinematheque brought some of the films that had impressed me during my DC stay. There was a Saturday marathon of The Iced Bullet (1917), Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915), The Bargain (1914), Will Power (1913), and The Man from Home (1914). For our Film Studies Colloquium across two Thursdays we screened False Colours (1914; incomplete), The Case of Becky (1915), Idle Wives (1916; incomplete), and Ben Blair (1916). Some of these I’ve written about in earlier entries, here flagged by links.

The Saturday screenings were accompanied by the lively, indefatigable playing of David Drazin. David worked for many hours and without having seen the films in advance. He’s a superb artist.

Seeing the films again, of course I found more to say.

Revival and revision

The Case of Becky (1915).

One of the secondary arguments in Reinventing Hollywood is that many storytelling techniques of silent film subsided during the 1930s but were revived during the 1940s. Silent films were full of dream sequences, subjective points of view, fantasy projections, and flashbacks. Those got elaborated and consolidated for the sound cinema by Forties filmmakers.

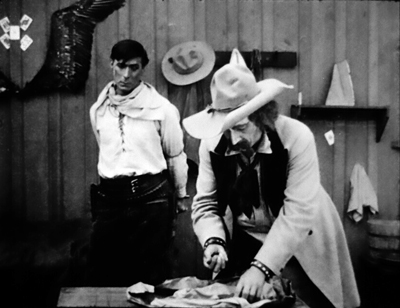

So it wasn’t surprising to find that The Bargain, a fine William S. Hart western, squeezed a lot of mental imagery into a single scene. The Sheriff has arrested Jim Stokes and retrieved the money he stole. Lashed to the bedpost, Jim remembers his wedding and the woman he’s betrayed, presented in a slow dissolve to the past.

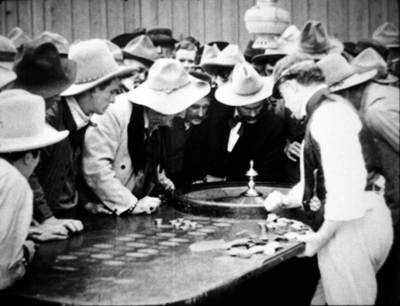

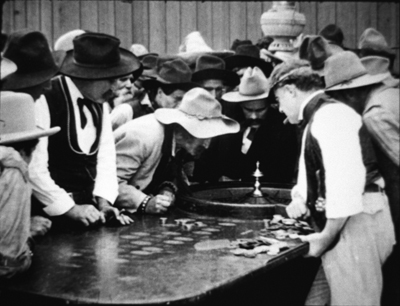

Meanwhile, downstairs in the saloon casino, the Sheriff succumbs to an impulse and loses all his money at roulette. Then he remembers, via another dissolved-in flashback, that he scooped up the stolen money too.

Back in the present, he digs that money out of his poke and bets it—and loses.

Later, in the hotel room, Stokes learns of the Sheriff’s folly and has a good laugh. But then he imagines Nell waiting for him, shown in a split-screen image.

At which point the Sheriff imagines his telegram arriving at his town, announcing Jim’s capture and the recovery of the money. That vision reminds him that he can’t return without the money he has squandered.

This makes him strike the central bargain with the thief he’s captured.

In a 1930s film, these visualized memories would most likely be presented verbally, as part of the stream of dialogue. (“When I think of marrying Nell….””I’ve promised to bring the money back…”). But 1910s American films tended to use dialogue titles sparingly; a lot of the films we saw asked the viewer to grasp the situation without benefit of words. The Bargain has only nineteen dialogue titles in 77 minutes (at 16 frames per second).

The Bargain is a good example of how purely pictorial storytelling was used to explicate a situation. Interestingly, today’s films are rather close to this tendency: fragmentary flashbacks and mental visions are common in mainstream movies.

Another echo struck me, this time in The Case of Becky. This is an early story of split personality, a narrative premise popularized after The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Here the young woman Dorothy (Blanche Sweet), under the sway of the sinister hypnotist Balzamo, develops a second identity, the surly and disruptive Becky. Becky isn’t really very dangerous, but when a young doctor, himself a master of hypnosis, falls in love with Dorothy, he determines to cast out Becky. He does so in a passage of intense mind control, visualized through a double exposure of Becky departing Dorothy’s body.

What interested me is that the same visual device was used by Arch Oboler in Bewitched (1945), one of the earliest psychoanalytical films of that era. The heroine’s two sides are summoned up by the shrink.

I suspect that Oboler got wind of the Selznick/Hitchcock Spellbound (1945) and rushed a B-film into production. (He could move fast because he adapted one of his radio plays.) Bewitched was released five months before the Selznick/Hitchcock film. It’s not great movie, but it has a sort of pre-Psycho pitilessness, and it’s always nifty to see a 40s film picking up on a silent-film device.

Cutting things up and filling the corners

My main research questions about the 1910s revolved around stylistics—matters of staging, lighting, shot scale, variety of camera setup, and editing choices. For about twenty years I’ve been exploring how, to put it broadly, the long-take, intricately staged tableau cinema was largely replaced by films dependent on continuity editing. By focusing on the years 1914-1918, I thought I could track the transition in finer grain.

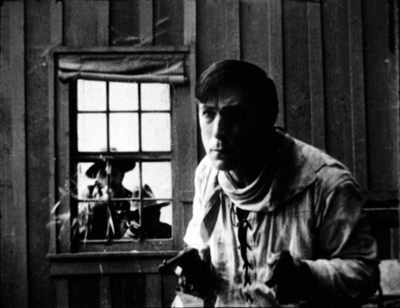

Many films were already building their scenes out of several shots. Go back to The Bargain, from 1914. A series of shots shows Stokes surrounded at the door and window, while also giving us a brief shot from a new angle incorporating tight depth, as the men at the window get the drop on him.

This freedom of camera placement within a single set is typical of the Hart films (see here and here), and of other films by Reginald Barker. It was sometimes visible in Alias Jimmy Valentine from the year before (1913), but it’s more pronounced in The Bargain. Several scenes in the hotel room where Stokes is tied up display a fairly wide array of camera setups.

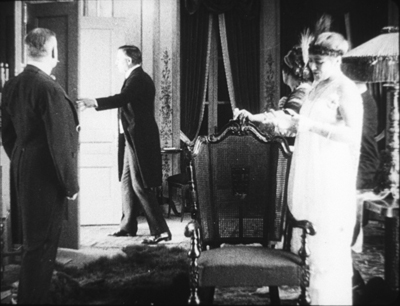

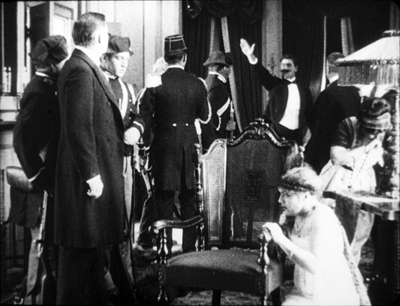

At the other extreme, The Man from Home (1914), credited to Cecil B. De Mille and Oscar Apfel, displays the tableau approach in full bloom. One long take at the climax shows a packed salon. To take just the high points of some pretty dense choreography: Ivanoff bursts in to confront his errant wife, who crumples in the lower right.

Pike holds off the Earl of Hawcastle, now partnered with Ivanoff’s wife. Hawcastle rushes to the right rear to open the curtains (stepping into a spotlight). Summoning the police, he returns to the middle ground to demand the arrest of the fugitive Ivanoff.

But a functionary arrives in the background, lifting his arm to signal the arrival of the bearded Grand Duke Vasili. Vasilii stalks in to take command of the middle ground and confront Hawcastle. Throughout. shrewd shifts of actors’ position open pockets of action, and the performers turn from the camera to drive our eye into depth.

Throughout most of this tableau, broken by occasional titles, Ivanoff’s treacherous wife is crouching in the lower right. This is an example of the “all-over staging” we find in 1910s cinema. Often corners and edges of the frame will be activated and demand to be noticed. For example, in The Bargain Stokes is observing a scene through a window. Cut inside the room, and Stokes can be seen way off to the right in a single pane.

Later directors would have placed the window nearer frame center so that Stokes’ face would be more quickly noticed.

Sometimes we find the filmmaker trusting the audience—or at least a modern audience—too much. In Ben Blair (1916), Ben is lured into a brothel and pulls his pistol in order to escape. But in the master shot, off to the right, the astute viewer can see the louche Sidwell, who’s aiming to marry Flo, cozying up to a hooker before he rises to flee the room. He has already met Ben and fears being recognized.

Director William Desmond Taylor doesn’t supply what I expect Barker would provide: a separate shot of Sidwell seeing Ben and rushing out of the room. Nor does Taylor provide a gradually unfolding tableau that would, by means of figure movement, frontality, centering, and other cues build to a crescendo revealing Sidwell’s presence—the sort of thing we see in The Man from Home. As it is, many viewers may miss the main point of the scene, which is to divulge Sidwell’s sexual betrayal of Flo.

But maybe this was best. Cutting straight in to Sidwell might have suggested that Ben recognizes him immediately. But he doesn’t. As Ben turns, Sidwell is ducking away. Ben has revealed, and seems to be concentrating, on a new center of interest, the woman who’s impudently blowing out cigarette smoke at him. He, like us, is distracted from Sidwell’s departure.

Still, we’re supposed to spot Sidwell even if Ben doesn’t. Only much later, after Sidwell has nearly convinced Ben to give up on courting Flo, does Ben realize that it was Sidwell he saw in the brothel. That’s done through a split-screen flashback of Sidwell starting guiltily beside his floozy.

Again, the shot is a little clumsy in showing Sidwell looking toward the camera, as if Ben saw him directly; but it seems to be another mental image, representing Ben’s now-clear impression that Sidwell was in the brothel.

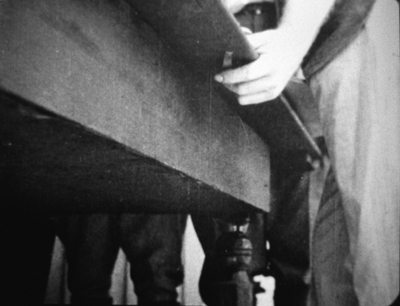

We don’t have to puzzle over such matters in The Bargain. Barker had mastered the precision necessary for off-center details. When the Sheriff is risking his money at the roulette wheel, a close-up reveals that the croupier is controlling it.

But here’s the neat part. At the turning point, when the Sheriff loses everything, Barker gives us close-ups of the Sheriff and the croupier, but not the hand pressing the button.

We’re sufficiently trained to spot the croupier pressing the button in the long shot (again, off-center). There’s no need to show the gesture again because the priming close-up has told us the game is fixed. Interestingly, that insert shot doesn’t come at the very start of the Sheriff’s gambling jag, so initially we might think the wheel is honest. We get the revelation just when the Sheriff is about to bet the money he can’t afford to lose. That boosts the dramatic tension.

Movies within movies

The Iced Bullet (1917).

While stylistics was my prime research focus, I couldn’t help but notice some bold narrative initiatives. A good example of a playful one was The Iced Bullet (1917), which has a Russian-doll structure (like many 40s films).

The inner tale recounts how a scientific detective solves an attempted murder, one using the method tipped in the title. But that’s swallowed up in a prologue and epilogue showing a foppish author crashing the Ince studio. He manages to interfere with filming, evade the guards, and take refuge in an executive’s office. He has brought along his screenplay, The Iced Bullet, which he hopes to direct and star in.

At the desk he falls asleep and dreams the detective story we see. At the film’s end he wakes up and flees the studio, pursued by watchmen. One trade paper of the time suggests that the comic frame story was devised in order to expand and elevate the murder story–which may explain why the film has been credited to both Reginald Barker and Charles Swickard. Maybe one directed the frame story and one the embedded one.

As the frame story stands, it offers us not only a comic pretext but precious views of the vast Ince studio.

There are also some nerdish in-jokes. C. Gardner Sullivan, author of the whole film we see, appears as the executive whose office is commandeered, while Barker shows up as a raging director trying to get the aspiring screenwriter off the set.

And when that invader takes over Sullivan’s office, he scoffs at a huge bust of William S. Hart, by now a major star.

The year before, Lois Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley had given us a more intricate film-within-a-film structure. The central story of Idle Wives centers on the plights of three women. Anne Wall is a wealthy but disillusioned wife who leaves her husband John to take up settlement work. She lives with Alberta, who has married John’s brother Richard. The couple has been disowned by John’s mother and sister. In her charity duties Anne meets Molly Shane, who has left her family to run off with the no-good Larry. Anne helps Molly through her pregnancy and reconciles her with her family. John, seeing how Anne has changed the lives of unfortunate women, welcomes her back and faces down the disapproval of his mother and sister.

This story is enclosed within another one, involving three other women. The Jamiesons, though wealthy, have an empty marriage. When Jamison meets an old girlfriend, they decide to go see a movie. They’re trailed by Mrs. Jamieson. At the same time, Mary Wells disobeys her mother and goes out with the thug Tough Burns. They wind up going to the same movie theatre. And the poor, hard-working Smith family, whose daughter is longing to escape, decides to take a day off and go to the theatre as well. All of them join the audience for Life’s Mirror, a film by none other than….Lois Weber. It stars Weber and Philips Smalley, who’s given his own poster.

This frame story, not in the source novel, is pretty stunning. In the first reel the people assemble at the theatre, which, as you see up top, flaunts the Weber-Smalley brand. These scenes are fascinating representations of moviegoing culture of the time, showing the ticket booth and the auditorium.

Just as important is the way that seeing the movie affects the characters in the frame story. Shots show people in the audience reacting to the fictional world.

The point of the film is that the characters, recognizing their counterparts on the screen, improve their behavior. Cinema is granted the power to divine the problems of its audience, and to heal their lives.

Or so we’re told from contemporaneous synopses. Because, in one of the great losses of American silent cinema, we have only the first and second reels of Idle Wives. Fortunately, those constitute the prologue and the initial exposition of the inner story.

How does the frame story turn out? According to the fullest contemporary account I’ve seen, in the epilogue Jamieson sees his wife weeping in the aisle, sends her rival away, and reconciles with her. Mary is shocked into realizing the risk of dating Tough Burns, who seems ready to reform after seeing his fictional double behave so cruelly. The Smiths agree to be kinder to one another, and the daughter of the family realizes the danger of fleeing home.

Two network narratives, then, in a single movie. Idle Wives has over twenty individuated characters, linked by kinship or domestic circumstances. (For instance, in both stories some characters live in the same building.) It becomes didactic, as Weber’s films often are, with the theatre presenting a placard that underscores the lessons, and opening titles that address the audience directly. Idle Wives was fairly described by a review as “a preachment on the sacredness of the home, also on the power of the motion picture.”

For most film historians, the great experimental film of 1916 was Intolerance, another tale of parallel situations and fates. But the same month that Griffith’s ungainly masterpiece was released saw the appearance of Idle Wives—in its way, no less daring, and by today’s standards startlingly modern. How many other remarkable films have been lost or have gone unnoticed? Like archaeologists excavating a site, we have a lot more digging to do to understand the glories and unpredictable experimentation of the cinema of the 1910s.

Thanks to my hosts at the Kluge Center last spring: Ted Widmer, Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello, as well as the team in the Moving Image Research Center–Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, Rosemary Hanes, and Alan Gevinson–along with the Culpeper dynamic duo Mike Mashon and Greg Lukow. We in Madison are especially grateful to Lynanne Schweighofer and George Willemen for preparing a reconstructed version of Ben Blair. Thanks also to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach for arranging the Madison screenings.

Some of David Drazin’s piano accompaniments are available on DVDs from Texas Guinan (that’s right, tguinan at aol.com).

Idle Wives has been posted online by the New Zealand Film Archive and the Library of Congress. An informative puff piece from the era is “The Smalleys Turn Out Masterpieces With Actors or With Types,” The Moving Picture Weekly 3, 14 (18 November 1916), 18-19, 26. The most comprehensive guide to Lois Weber’s career is Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015). I discuss the Smalleys’ little masterpiece Suspense (1913) here. Reinventing Hollywood has a chapter on the psychoanalytic cycle of the 40s, including Bewitched.

On all-over staging, and bungling the tableau, see the entry “Looking different today?” We have some entries on decentered framing, one on Mad Max: Fury Road and another on Fritz Lang’s use of corner frame space.

Idle Wives (1916).

The Fabulous Forties once more: REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD spreads out on the Net

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

DB here:

A couple of weeks ago, when I was in New York for the Museum of the Moving Image series based on Reinventing Hollywood, I also met with Violet Lucca, who runs the admirable Film Comment podcast. She and Imogen Sara Smith talked with me about the book. Our conversation is here.

Our session helped me to develop, somewhat babblingly, points I only touched on in the book. For example, there’s the idea that 1940s films aimed at a certain “novelistic” density (or heaviness, if you’re not sympathetic to them). That’s opposed to the fast-paced “theatricality” of many 1930s films. Of course there are exceptions, and complete outliers like The Sin of Nora Moran, a favorite of mine that Imogen mentioned.

Likewise, I got to reemphasize how filmmakers transformed conventions from fiction, theatre, and radio. And Violet and Imogen were right to draw me out on the role of the screenwriter, which I emphasized more than in my previous research.

It was not only fun but illuminating. Violet and Imogen are very knowledgeable and offered me many good ideas that expanded or nuanced things I tried to say. For example, Violet asked whether the “competitive cooperation” of the 1940s has an echo today. That seems right. Imogen suggested that the emergence of voice-over allowed actors to develop an impassive, internalized acting style characteristic of the 1940s. I wish I’d thought of that. In fact, I wish I’d talked with this pair before I wrote the book.

And yes, Daisy Kenyon is involved.

Also a click away from you is an extract from the book put up on Lapham’s Quarterly. It pulls a section from the first chapter about how amnesia works in popular storytelling. Maybe you’ll find it interesting.

Finally, Daniel Hodges kindly spotlighted Reinventing Hollywood in his very serious, in-depth website devoted to problems of film noir. While my book doesn’t say much about noir, since that wasn’t an operative category for creators of the period, my discussion of the woman-in-peril plot chimes with his very detailed study of many films in this vein. In addition, Daniel offers subtle suggestions about less-discussed sources of noir visual style, and he makes a strong case for spy films as being as important to the trend as hardboiled detective stories.

Thanks to Violet and Imogen for a very enjoyable hour, to Daniel for the link, to Lapham’s Quarterly, and to Rodney Powell and Melinda Kennedy of the University of Chicago Press.

The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).

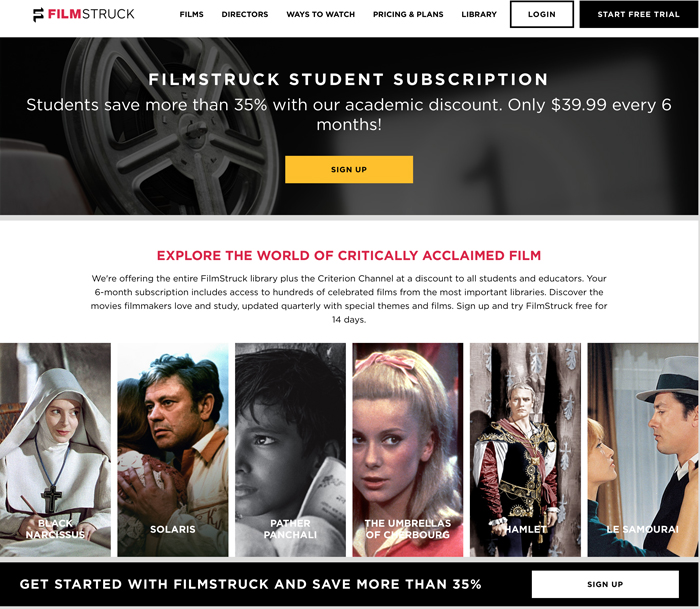

The Celestial Arthouse: FilmStruck and Criterion Channel with an offer hard to refuse

DB here:

Here’s the big news. FilmStruck has instituted a student rate for subscriptions: 35% off the monthly rate, which means $39.99 for six months, or less than $7 a month. The Criterion Channel is included in this deal. Not only students but educators are eligible; it applies to anyone with an email address ending in .edu. You can get more information here.

In the current context, this seems to me a real bargain. Cord-cutting and cord-shaving are making streaming more and more common. But at least your cable subscription bundled a lot of channels offering movies from a wide range of sources. Now we face the prospect of each “content owner” setting up a dedicated streaming service.

Netflix and Amazon and Apple and YouTube are funding and buying exclusive rights to films and TV shows. Hulu remains as a source of Disney, Fox, and Warners properties, but that bundle is coming untied. Disney is planning to claw back most of its films for its proprietary streaming service. How soon before other studios mount their own streaming services?

The total cost of subscribing to your favorite services may rival a cable bill. Recognizing this, the studios have banded together to merge access to several of these sources in an app called Movies Anywhere. But that’s for convenience; you’re still paying out to many providers.

Ten years ago, Kristin and two major archivists expressed skepticism about the arrival of the Celestial Multiplex. Never would everything–really, everything–be available. In fact, as licenses expire and Peak TV drives streaming, Netflix and other services have trimmed their foreign and classic libraries.

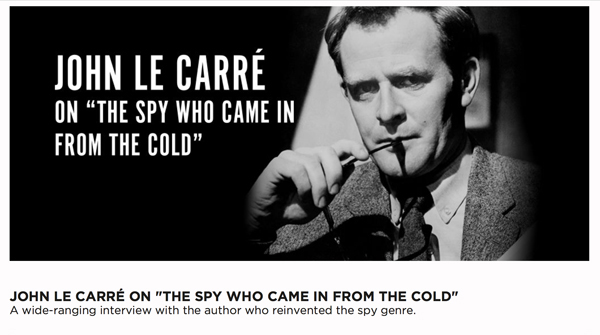

This makes film FilmStruck an even more stupendous opportunity for film lovers. It remains a big, fat aggregator. Where else can you see, on a single night, a cache of 80s indies, eight movies by Phil Karlson, seven by Herzog, seven from Tunisia, Toshiro Mifune slicing and dicing his adversaries, a rare trove of French films made under Nazi Occupation, and several debut films by major filmmakers? And that’s before you get to the Criterion Channel, which currently offers Belle de Jour, Kore-eda’s Still Walking, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (with a unique le Carré interview), The Color Wheel, and hundreds of other titles. Not the Celestial Multiplex, but close to a Celestial Arthouse. It’s what the prophets of cable TV told us to expect, but never arrived: access to world culture, at the time and place of your choosing.

I get it, dude. Movies.

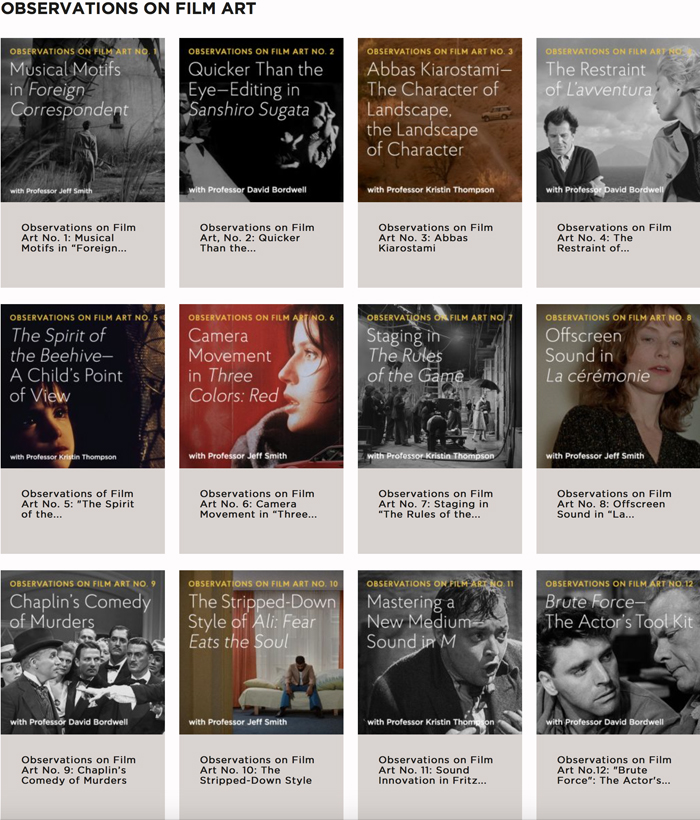

Criterion’s new deal comes at the one-year anniversary of our series, “Observations on Film Art.” Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have posted twelve installments, with more in the works. You can access them here, if you’re a FilmStruck subscriber. Several of these are developed further in blog entries; just go to our FilmStruck tag.

The anniversary set me thinking about streaming as a way of accessing movies. For home viewing I prefer discs, but more and more I watch streaming, usually to help my research. Several obscure 40s films I studied for my new book were available only on Amazon Prime, so those got my attention. Likewise, while revising our film history text, we checked on foreign-language titles not available on disc. But now I realize that to keep up with independent films I need to stream. The quite good I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore didn’t get a theatrical release and doesn’t seem to be on DVD.

What startles and sort of dismays me most is the way Netflix and other services let recent releases swamp the classics and imports they still have. I’m also a bit put off by the vastness of the choice, the grid of thumbnails like stamps in a huge album. A friend told me of her husband browsing titles for so long that they give up deciding on a movie and opt for the latest episode of a TV show.

Video stores were also vast, but they came with benefits. Rereading Tom Roston’s enjoyable I Lost It at the Video Store: A Filmmakers’ Oral History of a Vanished Era, I was reminded how important gatekeepers and tastemakers are. The best rental shops had knowledgeable clerks, wild categories, and displays that highlighted choices by staff. What we now call “curation” was in place, sometimes in a gonzo way, to guide people through the mass of VHS boxes. Kevin Smith:

I’d try to tell people what to rent even if it was the same stupid shit over and over. I was like, “I get it, dude. Movies. Who gives a fuck what they are.” I loved talking with people. There was no Internet, so you couldn’t jump on a message board or Twitter. “This is what I loved about Guardians of the Galaxy. I am Groot! #fuckin’thismovierocks.” You didn’t get to do that. You gotta do that in person with people.

FilmStruck, while offering hundreds of titles, has regained some of that curatorial function. You can still wander freely through the catalogue, but there are also interviews, talking-head introductions, categories both obvious and imaginative, and video essays of the sort you’d find in DVD supplements. For our series, we try to hold onto a personal touch. The installments are monologues, but we think we’re steering you toward what to appreciate in the movies we talk about. At least there’s a little more sense of human contact that way. And we hope our enthusiasm shows that analyzing film aesthetics doesn’t have to be dry and bloodless.

Thanks as ever to our collaborators at Criterion: Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and their colleagues.