Archive for 2017

Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction, and (sometimes) recovery

Kristin here:

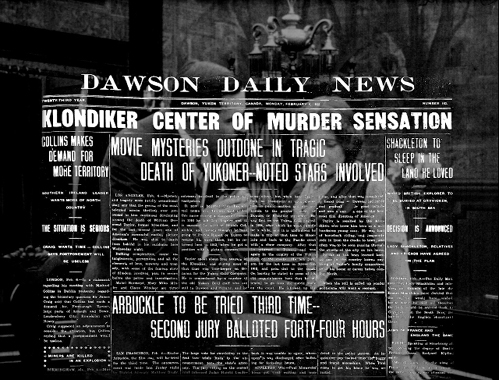

Many readers of this blog have heard of the Dawson City Film Find (hereafter DCFF), as it is called in Bill Morrison’s extraordinary documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time. How in 1978 work on a construction site in Dawson City, Canada, led to the discovery of hundreds of reels of nitrate films packed into a swimming pool in 1929, covered over, and forgotten. How these reels turned out to be from silent films, mostly from the 1910s, many of them previously thought entirely lost.

Few will know the story in the detail with Morrison provides, nor will they know the rich historical context that he provides for the discovery and recovery of the reels. His film is not, however, simply a presentation of the DCFF. It’s about growth, loss, recovery, and destruction in several areas, all circling around Dawson City as their hub. The subtitle “Frozen Time” is a bit misleading. The reels of nitrate sealed away in the permafrost were no doubt frozen, and the temporal fictional and newsreel images they contained were lost for decades.

Morrison, however, weaves information about a variety of other subjects together in a way that makes the passage of time palpable for us. We see its effects on people and places and discover the odd, fortuitous connections among them in a dizzying fashion.

A complex film like this deserves an extended commentary, which I offer below. There are spoilers galore in it, and I would suggest seeing the film before reading this. It should appeal to anyone interested in early cinema, in North American history, and in documentaries in general. Kino Lorber has recently released Dawson City: Frozen Time on Blu-ray, with extras including eight films from the DCFF.

Easing into the past

The films-in-a-swimming-pool hook is what Morrison uses to lure us into his larger historical weave. He begins with a hint of the recovered footage, showing a baseball game which will later be revealed as the scandalous 1919 World Series where White Sox players were bribed to throw the deciding game. Then we see briefly see Morrison himself being interviewed by a talk-show host, followed by a lady in 1890s costume enthusiastically introducing a premiere screening of some of the restored films for an audience in the Palace Grand. That theatere is a modern reconstruction of the first theater built in Dawson City, used for live drama, opera, eventually films, and other forms of entertainment.

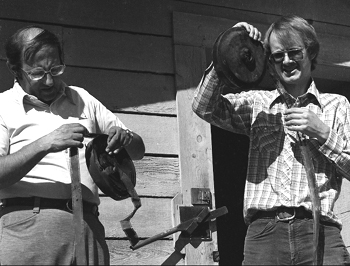

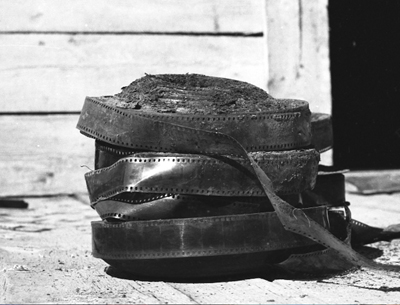

We move by stages back into history. Fifteen months before the premiere the discovery was made: a man running a back hoe turned up reels and coils of film. We meet the protagonists of the film-discovery portion of Morrison’s tale: Michael Gates, curator of Collections at Parks Canada from 1977 to 1996, and Kathy Jones-Gates, Director of the Dawson Museum from 1974 to 1986. She was Kathy Jones at the time of the discovery; this tale even has a romance, since the pair married after working together on the recovery of the buried reels. The couple describe the initial find, over still photos of mud-covered reels taken with Jones’s camera (above).

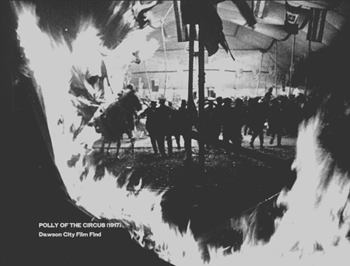

Morrison now takes us further back, to demonstrations of how nitrate film was made (with extracts from a 1937 film optimistically titled Romance of Celluloid) and how it is prone to catch fire and burn fiercely. The well-known 1897 Charity Bazaar disaster in Paris is cited, while film of a burning tent and fleeing spectators is shown. No visual record survives of the Charity Bazaar disaster, not even photographs. News accounts used engravings as illustrations. The burning tent footage is from a film released twenty years later, Polly of the Circus (1917), one of the main lost films recovered in the DCFF.

Morrison does not hide this source but superimposes a caption giving the film’s title, date, and source. This is the first time he draws upon DCFF images to evocatively represent real historical events. Later in Dawson City, the mention of an actual person, such as Gates, sending a letter will be accompanied by a montage of letter-reading moments culled from DCFF films. It’s a clever way to add a little humor and to show off a wide variety of the titles without dwelling on long clips from any one film.

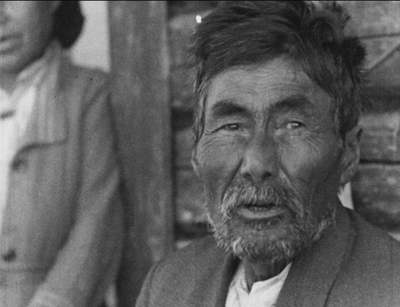

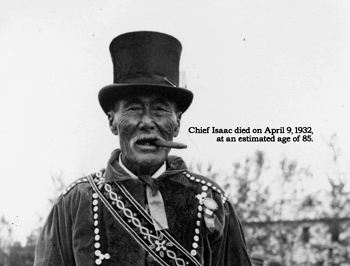

Having established the destructibility and danger of nitrate, Morrison flashes back to the earliest period portrayed in the film. Epic photographs show forested landscape. The narration, done with captions rather than voiceover, informs us that for millennia the area where the Klondike River flows into the Yukon has been the hunting grounds for one of the First Nations, the “native Hän-speaking people.” (The footage is from City of Gold, the famous 1957 Canadian documentary about Dawson City, which will become more important later in Morrison’s film.) A photo introduces Chief Isaac, leader of one subgroup of the Hän.

Nothing is said at this point, but the fate of these hunting grounds initiates one of the major threads recurring through the film, that of ecological destruction.

The third major thread is the history of Dawson City itself, which is as fascinating as the story of the buried films. In late 1896 or early 1897 one Joseph Ladue claimed 160 acres as a town site, where he sold lumber and lots to prospectors. By the summer of 1897 there were 3500 residents, and Morrison uses population figures to trace the wide swings in the town’s fortunes over the decades.

At this point the Northwest Mounted Police relocated the Häns’ village five miles downriver, and their fishing and hunting grounds were destroyed by mining.

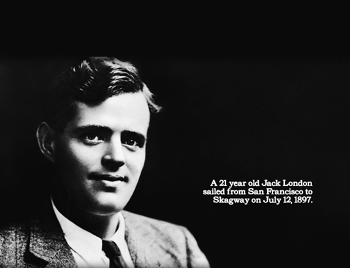

During the descriptions and facts about the huge amounts of gold coming out of the area, Morrison introduces other motifs and threads. He mentions that Jack London was among the prospectors. He was the first of several writers and theater figures who were in the Yukon, often during these early years. Most of them resurface late in the film later on, turning out to have surprising connections with the history of the cinema and each other.

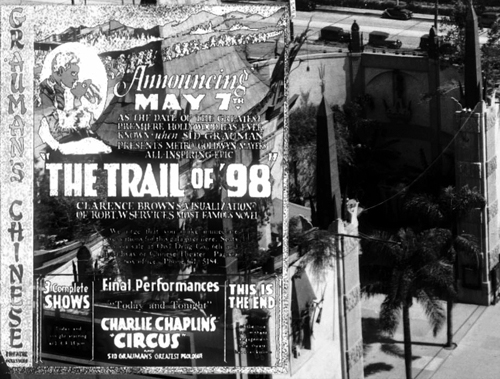

Famous entrepreneurs of later years got their starts here. Sid Grauman was a newspaper boy who eventually went on to build a theater chain, including the Egyptian and Grauman’s Chinese in Los Angeles. Ted Richard, who staged boxing matches in the Monte Carlo theater, later founded the New York Rangers and rebuilt Madison Square Garden. Alex Pantages started as a bartender, rebuilt Dawson City’s Orpheum theater after it burned to the ground in 1899 and showed traveling programs of early movies. He became one of the first major film tycoons, building a string of 70 theaters in North America.

The Gold Rush frozen in time

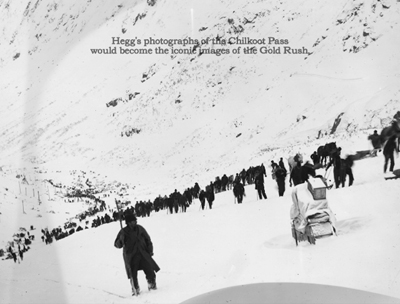

One of the revelations of Dawson City is the work of photographer Eric Hegg, who traveled to the Yukon alongside with the hordes of hopeful prospectors. He, however, worked as a photographer, and shot thousands of images that became, as Morrison’s caption says, “the iconic images of the Gold Rush.” The one above shows the arduous and crowded journey up over the notorious Chilkoot Pass. Chaplin later staged a remarkably similar scene for The Gold Rush (1925), though whether he could have seen Hegg’s images is unclear.

By the summer of 1898, the population of Dawson City was around 40,000, and the richest claims were all taken. Businesses were set up to cater to the prospectors, including Hegg’s photographic studio. Saloons, casinos, theaters, as well as more practical boat-builders and banks sprang up. Of the two initial banks that opened branches, the Canadian Bank of Commerce is the more important to Morrison’s story, since it eventually acted as the Dawson City agent for distributors sending films to town.

The first boom ended in the spring of 1900, after the announcement of a gold strike in Nome. Three-quarters of Dawson City’s population left, including Hegg, who left his collection of glass negatives with his partner, Ed Larss. He opened a new studio in Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush.

After his departure, Hegg disappears from Dawson City for quite some time. His work there, however, was also fortuitously rescued from oblivion. Twenty minutes from the end, we are introduced to Irene Caley and Will Crayford, who married in 1947 and decided to move a cabin from Dawson City to Rock Creek. Inside the walls they found hundreds of Hegg’s glass negatives. How they got there is unknown. Coincidentally, Hegg died in 1947, presumably unaware of the recovery of his early negatives.

The newlyweds proposed to strip the emulsion off the plates and use them to build a greenhouse. Luckily a local shopkeeper recognized their nature and gave the couple plain plates in exchange for the 93 glass ones, as well as 96 nitrate negatives. He donated the collection to the National Museum of Man in Ottawa. Arguably this rescue is as significant as the DCFF, especially given that Hegg’s photographs mostly survived in beautiful condition and constitute the best record of the Gold Rush’s first stage.

In 1949 a book of Hegg’s photographs, edited by Edith Anderson Bccker, was published as Klondike ’98.

Subsequently documentary film director and producer Colin Low saw the plates in Ottawa and was inspired to make City of Gold (1957), co-directed by Wolf Koenig. City of Gold, which drew extensively on Hegg’s images, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Short Film. The awards ceremony took place at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles, built and owned by the same Alexander Pantages who launched his theatrical career in Dawson City. It would be nice to think that whoever attended that ceremony representing City of Gold saw the connection.

In 1900, Hegg moved to Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush. His post-Dawson City photographs also survive. The University of Washington’s collection contains over 2100. Its library offers a short biography and a generous sampling of those photographs here.

Weaving the threads together

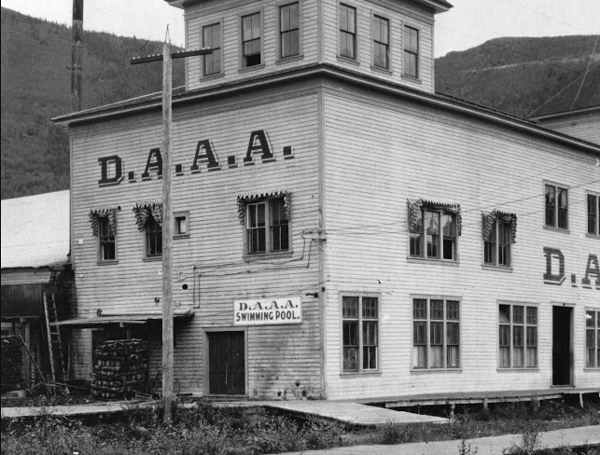

Dawson City’s second boom was less spectacular but more ominous. The White Pass Railroad made Dawson City more accessible, and heavier equipment was brought in: giant hoses to break up the ground, sluices to convey the ore to a central locale, and so. Miners brought their families to live in Dawson City, with the population steadying at 9000. Various institutions, including banks, the Carnegie Library (above), and, in 1902, the huge Dawson Amateur Athletic Assocation (DAAA) building was built, with an auditorium, billiards room, bowling alley, skating rink, and swimming pool (top). I can’t summarize the whole film, but by this point Morrison has introduced enough people and places to start connecting them up in unexpected ways.

One such thread meanders like this. The celebrity motif returns at about this point, with Marjorie Rambeau (later to have a career as a character actress in movies from 1917 to 1957) performing in Dawson City with a traveling theatrical trouple. Rambeau is not significant here, but Fatty Arbuckle was also in the cast. This information is accompanied by a frame from Fatty’s Day Off (1913), a film discovered in the DCFF.

Shortly after this, we hear of two further celebrities-to-be who were in Dawson City. In 1908, poet Robert Service arrives to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and the following year he writes his first and best-known novel, The Trail of ’98 (1909), about the Gold Rush. From 1908 to 1912, William Desmond Taylor works as a timekeeper on a large gold-mining dredge belonging to the Yukon Gold Company, founded by Daniel and Soloman Guggenheim in 1907. These dredges handled most of the mining, throwing many out of work and causing Dawson City’s population to shrink to 3000. Huge dredges would continue to grind down the land for decades.

In 1912, Taylor left for Hollywood, where he enjoyed a short but prolific career as an actor and director, before, as Morrison foreshadows, his untimely death.

These people disappear for a time, and we learn that in 1911 the auditorium of the DAAA was turned into a movie house, the DAAA Family Theater. Other theaters in town went over to showing films. Morrison conveys this via an amusing montage of shots of people in cinema and theatrical audiences, all from DCFF films. He also provides a quick summary of disastrous nitrate fires during the early 1910s.

There follows a long interlude of coverage of the suppression of laborers and leftists during this period, in part to show off some of the newsreel footage preserved in the DAAA swimming pool. These include the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, the “Silent Parade” protesting violence against African-Americans in 1917, and the World Series scandal of 1919.This somewhat tangential though interesting foray into politics also serves to bring us forward nearly a decade.

The Solax studio fire, which also happened in 1919, provides a rather wobbly transition back to film and Dawson City as the end point of a film distribution line. The population has sunk to 1000 by this point. Since the films shown in the town during this decade were not shipped back to the distributor, many of them were stored in the basement of the Carnegie Library and continued to be through the 1920s.

A long, effective montage of shots from various DCFF films follows, beginning with people listening through doors and going through them, so that we get the impression of a giant house with dozens of people sneaking around. This is followed by shots of men attempting to embrace women and being repulsed.

The last of these is from The Kiss (1914), starring William Desmond Taylor. A caption announces his murder in 1922.

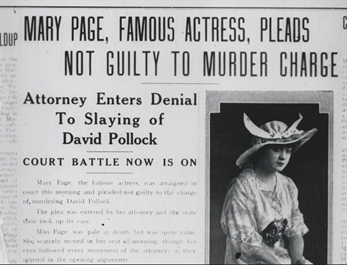

A Dawson City newspaper page announcing the murder and calling Taylor a “Klondiker” and a “Yukoner” is superimposed over another image from The Kiss. Coincidentally, just below this story is one about Arbuckle’s second murder trial ending in a hung jury. The second Taylor headline points out: “Noted Stars Involved.” One of these was Mary Miles Minter, and Morrison shows her in a film, The Little Clown (1921), from the DCFF. Minter had acted in films directed by Taylor, though this is, alas, not one of them. It was however, discovered among the DCFF films. Not one to quit there, Morrison cuts to a shot from another DCFF film, The Strange Case of Mary Page (1916), which has a plot that resembles Taylor’s case.

That two Hollywood directors should have been linked to murder cases, one as victim, one as alleged perpetrator (Arbuckle was never convicted), was certainly a gift to a director keen to stitch as many elements of his film together as possible through associations rather than straightforward historical causes.

Other connections are less elaborate. At the point where the story of Dawson City has reached the late 1920s, The Trail of ’98 (1928), an adaptation of the Robert Service novel mentioned above, is shown via a superimposed poster to be screening at Grauman’s Chinese, another chance confluence of two people who could not have crossed paths in the Yukon, since Grauman left there in 1900.

The burial

All this material has brought us to the point when the accumulating films in the library basement were transferred to the DAAA swimming pool. By 1928 Dawson City had developed a “modest season tourist industry.” Chief Isaac, whom we met early on, had become mayor of Moosehide (above). And Clifford Thomas, the man responsible for putting the film reels in the swimming pool, moved to Dawson City to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce. He also became the treasurer of the Dawson Amateur Hockey League, which played on the ice rink installed annually over the swimming pool.

In 1929 the library storage had reached capacity, and when Thomson inquired of the studios what he should do with the films, he was instructed to destroy them. At about the time, it was decided to fill in the pool so as to allow for a the skating rink to get rid of a broad bulge caused by the pool’s cover. Thomson made the decision to use the reels as fill in this conversion. Numerous other reels were burned or thrown into the Yukon River–a standard way of disposing of trash.

Morrison could have skipped back to the recovery of the films roughly fifty years later, but instead he continues the Dawson City story. First, he poetically indicates the long decades the reels spent sealed underground with a montage of women asleep, all drawn from DCFF films. The talkies finally reach Dawson City, and more silent reels are dumped or burnt. Chief Isaac dies in 1932.

Parades continue to celebrate the Gold Rush heritage, as recorded by George Black, an avid local amateur cinematographer who recorded several events shown in Dawson City. The one below took place in 1941.

By 1950, the population of Dawson City dropped under 900 people. The last theater was torn down in 1961, though the replica of the Palace Grand went up as a multi-purpose facility in 1962.

On November 15, 1966, the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation closed down its last dredge. A lengthy drone shot flies high over the tortuous, unnatural landscape that resulted from many decades of grinding down and spewing out the land (bottom). The ecological thread has not been emphasized through most of the film, but it comes to a devastating conclusion.

Morrison reaches the discovery of the reels in 1978, and Gates and Jones-Gates resume their story. They contact Sam Kula, Director of Audiovisual Archives, 1973-1989 at the National Archives of Canada. Kula comes to Dawson City, and he (left) and Gates (right) investigate the sodden reels of film.

Kula initially suggested donating the films to the local museum and contacted Kathy Jones. She helped dig up the films, which turned out to be far more numerous and buried far more deeply than they imagined. A newspaper item about the find led to a letter from Clifford Thomson. His explanation of how he had arranged for the films to be put in the swimming pool solved that mystery and provides us with our basic knowledge of the origins of the reels.

The rest of the film’s tale of the reels’ discovery follows how the three rescuers tried to ship the thems to the National Archives of Canada, with several truck, bus, and air services refusing to deal with nitrate film. In November of 1978 a Canadian Air Force plane delivered 506 reels to the Archives.

Morrison ends with a series of shots from various DCFF films with heavy deterioration. The thread of nitrate’s flammability and the recounting of numerous nitrate fires finds its quiet ending in the film’s lengthy final shot. A female dancer performs a modern dance that apparently expresses anguish. Blank white flashes flicker across the frame, suggesting that the dancer is being enveloped by the flames generated by nitrate film.

It is a fitting ending to a film that blends fascinating information and poetic associations in equal measures.

Some caveats

Despite my considerable admiration for Dawson City: Frozen Time, I have to take issue with some of the descriptions in this last part of the film. The narration does not point out that most of the films recovered were incomplete–not surprisingly, given how many reels were burned or otherwise destroyed. A film historian would assume that. A casual viewer would not. Similarly, there is an explicit statement that “every other copy” of these films had been lost to fire and decay. Some of these films, however, survived elsewhere, and sometimes in better copies.

The reception of the film has, through no fault of Morrison, distorted the significance of the DCFF considerably further. This evidently started with a extensive article in Vanity Fair that dubbed the DCFF “The King Tut’s Tomb of Silent-Era Cinema.” Numerous reviewers picked up this idea and repeated it, as when Kenneth Turan began his review, “It’s been called the King Tut’s Tomb of silent cinema, a celluloid find at one of the world’s far corners that dazzled the film universe.”

I cannot think of a more inapt comparison. Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of only two largely undisturbed royal tombs from the entire three-thousand-year history of ancient Egypt, and it is far and away the more important of the two. Despite the tomb’s small size in comparison with others in the Valley of the Kings, an extraordinary number of intact royal grave goods came from it–about 5000 of them (a small sample shown above). Indeed, most of what we know about ancient Egyptian royal grave goods is derived from those pieces. Tutankhamun’s tomb is, as far as we now know, unique.

In contrast, there have been many hundreds of discoveries of original silent films. One of the most notable is the Desmet collection in the Netherlands, which contained over 900 films, most of them complete and in excellent condition. Other such discoveries have ranged from single prints to large collections. Those who have discovered and restored these films are still building the international archival holdings of silent cinema. The Dawson City find is simply one important contribution to this extensive and ongoing effort.

Sam Kula himself wrote, “No-one familiar with the considerable resources now accessible through the work of film archives throughout the world would seriously argue that the Dawson Collection, or any one cache of early film, will lead to a wholesale re-write of the histories.”

The story continued

Morrison essentially ends his account when the films leave Dawson City, which is quite understandable. But the viewer might ask what happened next. There is little attention paid to the lengthy, complex procedures necessary to rescue the films from the effects of their long burial and to transfer their images onto modern negatives.

The Blu-ray release contains a nine-minute supplement, Dawson City: Postscript, which does trace some of the subsequent history of the rescued reels. We see the washing of the films in the Canadian facility, as well as the storage facilities in which the original films were stored once they had been duplicated. In the US, the Library of Congress’ 388 reels are now kept at the Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia, which David visited and blogged about earlier this year. Morrison maintains his history of Dawson City as well, noting that in the summer of 1979 the town suffered a disastrous flood and that the premiere of some of the restored films took place shortly after that, on September 1.

At first glance, the Dawson find seems to have been handled in a casual way, with local administrators who were not film archivists digging up reels with shovels and handling them in a way that today would seem reckless. Some have assumed that considerable unnecessary damage was done to the films after their discovery. Yet no written account of the whole affair has yet been published.

I asked our friend Paolo Cherchi Usai, Senior Curator of the Moving Image Department of the George Eastman Museum, for his opinion. He kindly gave me his account of the rescue process, which suggests that the original participants in Dawson City did the best they could under extremely challenging circumstances.

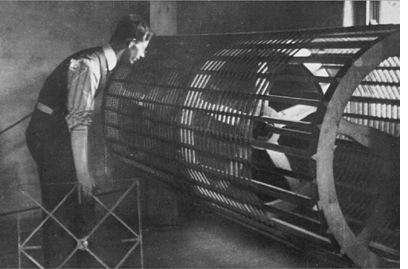

As Paolo wrote in introducing his description, “Please note that what I know is just a matter of oral history — things I heard from the protagonists and witnesses of the events, several years ago. Also, I have not yet seen Bill Morrison’s film.” Others may be able to correct or expand upon some of what Paolo has written. Still, it provides a very informative and useful summary of the rescue process. (I have identified the people mentioned below in brackets. The undated image of a silent-era drying drum is the only image in this entry that is not from Dawson City: Frozen Time.)

In my opinion, the rescue of the Dawson City was a miracle of improvisation and initiative achieved under extremely difficult and often adverse circumstances (see below). In all fairness, I can’t call it a disaster (I can think of other occurrences in my field where that term could rightfully apply). In hindsight, it is all too easy to point out the mistakes made in the process; back in 1978, archival practices were less sophisticated than they are now.

The comparison with Tutankhamen’s tomb is indeed excessive in regard to the aesthetic importance of the films; there is no exaggeration, however, in pointing out the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the discovery, and the steps taken in a very short period of time. You don’t find silent films in a frozen swimming pool that often. When you do, the historical value of the artifacts is not an issue. You want to save all the objects, and then find out their worth. That’s the main reason for the mystique surrounding the discovery; that’s also why I heard about it as soon as I started studying silent film history and film preservation.

It must be pointed out at the outset that the film reels found in the layer right under the permafrost that covered the swimming pool were already decomposed. Nothing could be done to save those prints. It is my understanding that preliminary identification work was undertaken at Dawson City, and that such work was implemented in a cold area. It may be argued that there was no particular reason why this work had to be done there instead than later in Ottawa, but that’s what happened. The late Sam Kula, one of the protagonists (together with Bill O’Farrell [Head of Film Preservation, 1975-2002, National Archives of Canada] and Paul Spehr [former Secretary for the Motion Picture Section of the Library of Congress and Assistant Chief of the Motion Picture Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress], among others) of this story, may have been able to explain this.

The reels gradually thawed in at least three stages, during their transfer to a) an air-force base near Dawson City; b) the National Archives in Ottawa; c) the Library of Congress. The thawing could perhaps have been minimized (if not avoided altogether) if the material had been processed in a refrigerated area from beginning to end. This didn’t happen. The nitrate unit at the National Archives of Canada had been shut down to make room for operations on safety materials, and no special precaution could apparently be taken while dividing the collection in two main groups: the Canadian newsreels to be kept at the National Archives, and the American films to be sent to the Library of Congress.

Bureaucracy was the nemesis of the Dawson City rescue project. The only way Bill O’Farrell could bypass it was for him to personally transport the reels of American films from Canada to the US by car, in a large station wagon, from Ottawa to Suitland, Maryland. His heroic feat — perhaps the most important of his career — would have hardly been possible today. He had no choice; following the usual protocol would have taken months, and the emulsion on the prints would have melted completely. Paul Spehr did his part by having the films accepted into the collection in record time, without following the standard acquisition procedures at the LoC. O’Farrell had alerted Spehr that “there is water in the cans” — this is what Spehr heard on the phone, and he expected this to be the case when the material arrived. It’s not that the reels were drenched in a pool of water in each can; but there was water. The prints had thawed.

In that situation, it was deemed necessary to do something about that water. The technical staff at LoC designed and built  a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

To reiterate the point, the whole story has always been described to me as an emergency rescue performed at breakneck speed, a chain of events where careful advance planning could not be part of the picture. The only way to avoid the partial loss of the emulsion would have been to undertake the entire process in a much colder working area. By the time the reels reached Dayton, however, it would have already been too late to apply such a solution, even if a low-temperature processing area had been available. All that could be done at LoC was to “stabilize” the material long enough for it to go through the printers for duplication.

So that’s that. I hasten to add that my recollections raise a number of questions to which I have no answer.

Our thanks to Paolo for filling in so much of the rest of the story of the Dawson City Film Find.

Thanks to Jonathan Hertzberg of Kino Lorber for his assistance.

The Sam Kula quotation comes from his account of the DCFF rescue, “Rescued from the Permafrost: The Dawson Collection of Motion Pictures,” which can be found on Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archvists #8 (Summer 1979), reprinted from American Film (July 1979).

A brief description of the “Public Archives of Canada/Dawson City Collection” is on the Library of Congress “Motion Pictures in the Library of Congress” page.

Dreyer, and more, in Houghton

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928).

DB here:

Erin Smith, of Michigan Technological University, distinguished herself during her years at Madison as a grad student in both English and Film. She’s moved more fully into media studies and production, including documentary work. When she invited me to visit 41 North Film Festival this coming weekend, how could I refuse?

There’s a lot going on, most elaborately a screening of Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc with orchestral and choral accompaniment.

I’ve never attended a performance of Richard Einhorn’s score, so this should be quite something. (The Criterion DVD version of the film offers it as optional accompaniment.) In addition, there are several other films showing over the weekend. You can go here for the full schedule, which includes one of our recent favorites, Varda’s Faces/Places.

While Kristin and I are there, I’ll be doing a lecture on Dreyer and another talk based on Reinventing Hollywood.

My first book was a little guide to La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, and my second book was a survey of Dreyer’s films. I’ve returned to him sporadically since then, and I’ve had occasion to rethink his role in film history–especially in light of my and others’ research on silent cinema. (For example, “The Dreyer Generation,” “Dreyer Re-Reconsidered,” “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic,” and this blog entry on Criterion’s Master of the House release.)

Dreyer remains for me an impressive, enigmatic figure. He was sensitive to the changing styles of cinematic expression from the 1920s to the 1960s, and yet he went his own way. His early silents were au courant with trends in European filmmaking, especially kammerspiel. Yet Jeanne was one of the wildest movies of the era, a hallucinatory blend of Expressionism, French Impressionism, and Soviet Montage. It still seems to me resolutely unique, which partly secures its timelessness.

After the no less weird Vampyr (1932), Dreyer’s films seemed old-fashioned in their pacing; even Danish critics called Day of Wrath (1943) sluggish. Yet as things played out his “archaic” style in the sound era looks more and more prophetic. He said he learned from Antonioni, but Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964; below) go far beyond the deliberate pacing of European films of his day and look forward to Straub/Huillet and Béla Tarr.

Was he the first director of “slow cinema”? I now see him as integrating principles of the “theatrical” cinema of the 1910s–a style he rejected in his youth–into the modern sound cinema, in effect showing the continued viability of the approach, while pushing it to extremes. Just like what he did with editing and shot design in Jeanne, come to think of it. For such a quiet guy, he was pretty bold.

Michigan Tech is located in gorgeous country (the UP, as we midwesterners call it). Kristin and I look forward to our road trip, accompanied by old Orson Welles radio shows. We thank Erin and her colleagues for inviting us!

A view of Houghton, MI, from the Portage waterway.

Biomechanics goes to the Big House: BRUTE FORCE on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

If there’s one film technique that probably everybody notices, it’s acting. Reviewers are obliged to judge performances, and viewers often comment that this or that actor was admirably controlled, or wooden, or over the top. Yet acting is surprisingly hard to describe; the critic who can do it engagingly, as Pauline Kael could, wins plaudits.

I think it’s fair to say that film analysts haven’t on the whole found good ways to analyze acting. There are books about historical acting styles, and there’s a very good theoretical overview by—no surprise—Jim Naremore. Our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have produced a superb study of acting in the early feature film, with careful attention to the conventions of the period. But I think there’s still more to be done in terms of analyzing how performers achieve their expressive effects.

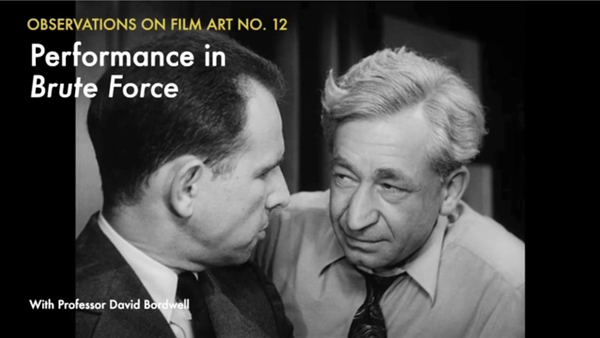

Or so I suggest in the newest installment of our series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel of FilmStruck. Using Brute Force as an example, I try to lay out in brief compass some primary tools that actors wield. There’s an excerpt here. Today I’ll sketch out what I tried to do.

Bits selected and amplified

Talk about acting tends to set “realism” or “verisimilitude” against “artifice” or “stylization.” The Method, we sometimes say, is an example of realism, while Expressionist acting à la Caligari is at the opposite pole. Classic Hollywood acting, from the late 1910s into the 1940s, we might say ranges across the middle.

Accordingly, some theorists of acting are realists, favoring one zone and finding the other too artificial. Others are conventionalists; they argue that all acting, even the most apparently realistic, is actually stereotyped. It looks realistic because we accept the conventions of a time or tradition as the way people actually behave.

I think it’s worth suspending this polarity and simply looking at how performances are built up out of pieces. Like Meyerhold’s Biomechanics and Kuleshov’s engineering approach to acting, my perspective here is that of seeing performances as clusters of controlled choices about specific bodily behaviors.

As a first approximation, I propose that acting of any sort starts with some norms of human facial, vocal, and bodily expression.

Many of those norms might be universal. I’m risking disagreement here, since the US humanities are predicated on a fairly radical relativism. But I think that’s implausible. Is there any culture where smiling reliably indicates unhappiness? When frowning and shaking your fist in someone’s face indicates affection? Where pointedly turning your back on someone shows a willingness to engage socially? Where sloping your shoulders, tipping up your inner eyebrows, rearing back your head, turning down your mouth, and wailing indicates joy rather than misery? (The guitar-hugging rocker’s cry of anguished teen spirit draws on the ensemble of cues we see in the mother cradling her wounded child.) Nobody expresses pride by dropping to a crawl.

The context can qualify or negate these signals, of course. One may smile and smile and be a villain. But exactly because cordial smiling isn’t the default signal of villainous purpose, Shakespeare is able to make his point about deception. Any expression can be faked; that’s what acting is. At bottom, though, taken singly and reinforced by other inputs and circumstance, there are some reliable expressive cues in the typical case.

But even if you believe in the social construction of everything, my point still carries. Humans in any community emit a stream of behaviors in face, voice, hands, posture, stance, and so on. Maybe those bits are wholly constructed socially, or maybe universal proclivities play a role too. In any case, what the actor does, I posit, is survey the range of such behavioral possibilities for the role she is to play. She then does two other things.

First, she selects only a few. Any performance depends on picking a few behavioral bits to carry expressive impact.

Second, at any given moment, the selected features are emphasized, even exaggerated. The actor bears down on the selected behavioral bit, dwelling on it. The clumsy, sometimes contradictory flow of real-life behavior gets simplified and streamlined for easy uptake.

For example, certain body parts may dominate the impression. If we’re to watch the hands, the face can be fairly neutral.

Correspondingly, in cinema the shot can be scaled to stress the one gesture—in this case, a pat of comradeship.

If we’re to watch the face, keep the hands and body still. Film technique can help you by recruiting our old friend the facial view. I talk about several examples in Brute Force, of which this is one of my favorites—two frontal faces, blatantly unrealistic but riveting (as Eisenstein knew; see below).

Only the eyes move, and one mouth, barely.

Or, if we’re to watch an eye-flick, keep the face neutral.

Indeed, you can argue that the development of the intensified continuity style, which concentrates on facial close-ups, gave the actors less to do with their hands and bodies than did the greater range of shot scales available to studio cinema from the 1910s to the 1960s.

To smack us with a bigger impact, the filmmakers add up the channels. In this scene of Brute Force, the commissioner takes control of the prison from the warden, and the two men’s facial expressions—determination on one, fear on the other—are amplified by their paired gestures of wrestling for the loudspeaker.

The effort shows not only in their postures and fingers but their faces.

At high points, we can go for all-over acting, face and gesture and bearing and voice, as when the snitch faces his fate in the machine shop.

But note that even here, as an ensemble element, other factors are neutralized. The attackers are seen from the rear and poised or moving stiffly and inexorably. Similarly, the pure animal outburst of Lancaster’s performance at the climax depends on several factors of expressive movement swept together.

Wounded, he lets his boiling rage explode; even the frame can’t contain him. But even here there’s selection and emphasis. The head and voice and straining neck do all the work, while the arms remain taut.

The tools I survey are simple ones: eye areas (not so much the eyes as the lids and brows), mouth, tilt of the chin; bearing and stance; hand gestures; and rhythm of walking. In the Observations installment, I look at how the performances in Brute Force play off against one another, and I sum up the resources in Lancaster’s fierce performance, using all of the tools he had. That wedge of a back. Those mitts. Those slightly shifting eyes.

For preparing the Criterion Channel installment, thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and all their colleagues.

The theatrical tradition is discussed by Alma Law and Mel Gordon in Meyerhold, Eisenstein, and Biomechanics (new ed., McFarland, 2012). On Kuleshov, see Kuleshov on Film, ed. Ron Levaco (University of California Press, 1974), pp. 99-115. I discuss Eisenstein’s approach to these problems, what he called mise en geste, in The Cinema of Eisenstein, pp. 144-160.

On actors’ use of eyes, go here; on hands, try this. I’ve discussed Lancaster’s skills before, here. More generally, when it comes to pictorial representation I defend a moderate constructivism against pure relativism here.

Ivan the Terrible Part II (1958).

Women, Oscars, and power

Kathleen Kennedy on the 1 January 2013 cover.

Kristin here:

Now that I have your attention …

We are now well into the season when award speculation begins. Well, actually Oscar speculation knows no season these days, but it snowballs between now and the announcement of the winners on March 4–at which point the speculation concerning the 2018 Oscar race revs up.

Among the issues that will inevitably come up is the question of whether more women directors will get nominated, especially following the critical and box-office success of Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman. It would be great to see more female nominees for Best Director, but the real problem is achieving more equity in the number of women being able to direct films at all. Unless more women direct more films, their odds of getting nominated will be low. Maybe the occasional Kathryn Bigelow will emerge, but overall the directors making theatrical features remain largely male.

Variety recently ran a story about initiatives to boost women’s chances in Hollywood. It stressed the low percentage of women in various key filmmaking roles:

The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University found that in 2014, women made up just 7% of the directors behind Hollywood’s top 250 films. Overall, of the 700 films the center studied in 2014, 85% had no female directors, 80% had no female writers, 33% had no female producers, 78% had no female editors and 92% had no female cinematographers.

Discouraging, except that there’s one figure that doesn’t support the lack of women. If 33% of films were without female producers, that means 67% had female producers–which is a lot better than in those other categories.

One thing that has struck me as odd is the lack of attention paid to the distinct rise in the number of female producers being up for Oscars in the recent past. This Variety article, however, is the first one I’ve seen offering numbers to show that women are doing a lot better in the producing field than in other major areas.

The missing names

Kathleen Kennedy, the lady illustrated at the top of this entry has produced seven films nominated as Best Picture, and she is considered one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. How could she not be? She produced Steven Spielberg’s films, alongside others, for many years and since October, 2012, she has been President of Lucasfilm in its incarnation as a subsidiary of Disney. She runs the Star Wars series.

In the Indie realm, producer Dede Gardner is on a roll, having since 2011 had three films nominated for the top prize in addition to wins in 2013 and 2016. Others, such as Megan Ellison and Tracey Seaward, have enjoyed multiple nominations. (I’m using the film’s year of release rather than the year when the award was bestowed.) As we’ll see, female producers are beginning to catch up to their male colleagues in number as well as prestige. Why no fuss about such important strides?

I think the main reason is that there’s no “Best Producer” category. If there were, I suspect our image of women in the industry would be very different. But there’s just a Best Picture one. In most cases neither the industry journals nor the infotainment coverage lists the producers alongside the titles of the Best Picture nominees. So who’s to know that the “Best Picture” race also is, faut de mieux, the “Best Producer” contest.

Another, perhaps less important reason why producers draw less attention is that because a film often has several producers. It’s more complicated to assign responsibility for who did what. Most people have a general idea of what directors do. They’re on set, they make decisions, and they supervise other artists. A female producer, like a male one, may have been included for many reasons. She might have done most of the work in assembling the main cast or crew members or she might have concentrated on gaining financial support. She might instead be termed a producer as a reward for crucial support at one juncture. We can’t know, and that perhaps makes it difficult for the public to get enthusiastic about producers. Of course, if journalists covered them more in the entertainment press, the public might gain more of a sense of what producers do.

Yet whatever their contribution, those producers played some sort of crucial role, and they are the ones who get up and receive the statuettes when that last climactic announcement of the evening is made. (Lately there has been a trend for the every member of the cast and crew and all their relatives present to rush onto the stage for a grand finale, but it’s the producers who give the thank-you speeches.) They can take those statuettes, with their names engraved on them, home and put them on their mantels or to their office to display in a glass case. Yet few have any name recognition outside the industry, the entertainment press, and a few academics.

Despite these producers’ importance, it’s difficult to find out who they have been over the years. Go to almost any website, including the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ own, in search of Oscar nominees stretching back through the years, and you will usually find names listed in all the other categories–but only the title of the nominated films in the Best Picture category. I finally found a complete list of Best Picture nominees’ producers compiled by an industrious contributor to Wikipedia. Going through and doing some counting and cross-checking, I have created and annotated my own list. With it I’ve tried to show the fairly steady progress that women have made in this category. I call them “nominees” below. Somewhat paradoxically, they win the Oscars, though technically the film is the official nominee.

To keep this list from becoming even longer, I’ve listed only nominated films which had one or more women among their group of producers. Up to 2008 there were five films each year. Starting in 2009 the number could be anywhere between five and ten, though it’s usually eight or nine. I give the number of nominated films starting in 2009. Assume any films not listed were produced by men. If you’re curious about who those men were, click on the link in the previous paragraph.

Here’s how things developed, including only years when female producers were “nominated.” (My comments in red.) Be patient. It gets off to a slow start, but things pick up.

And the nominees are …

1973 The Sting (WINNER) Tony Bill, Michael Phillips, and Julia Phillips.

Julia Phillips becomes the first female producer nominated since the Oscars began in 1927 and the first to win.

1982 E.T. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

The second female producer nominated.

1984 Places in the Heart. Arlene Donovon.

The third nominated female producer.

1987 Fatal Attraction. Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing.

The fourth nominated female producer.

1989 Driving Miss Daisy. (WINNER) Richard D. Zanuck and Lili Fini Zanuck.

Lili Fini Zanuck is the second female producer to win.

1991 The Prince of Tides. Barbra Streisand and Andrew S. Karsch.

1994 Forrest Gump. (WINNER) Wendy Finerman, Steve Tisch, and Steve Starkey.

The Shawshank Redemption. Niki Marvin.

Wendy Finerman (right) becomes the third woman producer to win a Best Picture Oscar.

This is the first year when two women are nominated. From this point to the present, there has been no year without at least one female producer nominated.

1995 Sense and Sensibility. Lindsay Doran.

1996 Shine. Jane Scott.

1997 As Good as It Gets. James L. Brooks, Bridget Johnson, and Kristi Zea.

The first year when four women are nominated.

The first time two women are nominated for the same film.

1998 Shakespeare in Love. (WINNER) David Parfitt, Donna Gigliotti, Harvey Weinstein, Edward Swick, and Marc Norman.

Elizabeth. Alison Owen, Eric Fellner, and Tim Bevan.

Life Is Beautiful. Elda Ferri and Gianluigi Brasch.

Gigliotti is the fourth woman to win a producing Oscar.

1999 The Sixth Sense. Frank Marshall, Kathleen Kennedy, and Barry Mendel.

First year when a woman producer, Kennedy, is nominated for a second time.

2000 Chocolat. David Brown, Kit Golden, and Leslie Holleran.

Erin Brockovich. Danny DeVito, Michael Shamberg, and Stacey Sher.

For the second time, two women are nominated for the same film.

2001 The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2002 The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2003 The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. (WINNER) Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

Lost in Translation. Ross Katz and Sofia Coppola.

Mystic River. Robert Lorenz, Judie G. Hoyt, and Clint Eastwood.

Seabiscuit. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Gary Ross.

Walsh is the fifth woman to win in this category.

Walsh and Kennedy tie for the first woman nominated three times.

The second year when four women are nominated.

2004 Finding Neverland. Richard N. Gladstein and Nellie Bellflower.

2005 Crash. (WINNER) Paul Haggis and Cathy Schulman.

Brokeback Mountain. Diana Ossance and James Schamus.

Capote. Caroline Baron, William Vince, and Michael Ohoven.

Munich. Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy, and Michael Mendel.

Cathy Schulman is the sixth woman to win.

The third time four women are nominated.

Kennedy becomes the first woman nominated four times.

2006 The Queen. Andy Harris, Christine Langan, and Tracey Seaward.

2007 Michael Clayton. Jennifer Fox and Sydney Pollack.

Juno. Lianne Halfon, Mason Novack, and Russell Smith.

There Will Be Blood. Paul Thomas Anderson, Daniel Lopi, and JoAnne Sellar.

The first year in which five women are nominated in this category.

2008 The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Céan Chaffin.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

First time a woman, Kennedy, reaches a fifth nomination.

The third time two women are nominated for the same film.

2009 The first year of up to ten nominations. Ten films nominated.

The Hurt Locker. (WINNER) Kathryn Bigelow, Mark Boal, Nicholas Chartier, and Greg Shapiro.

District 9. Peter Jackson and Carolynne Cunningham.

An Education. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

Precious. Lee Daniels, Sarah Siegel-Magness, and Gary Magness.

Kathryn Bigelow becomes the seventh woman to win in this category. (Right, with her producing and directing Oscars.)

The fourth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2010 Ten films nominated.

Inception. Christopher Noland and Emma Thomas.

The Kids Are All Right. Gary Gilbert, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, and Celine Rattray.

The Social Network. Pana Brunetti, Céan Chaffin, Michael De Luca, and Scott Rudin.

Toy Story 3. Darla K. Anderson.

Winter’s Bone. Alex Madigan and Ann Rossellini.

The second year five women are nominated in this category.

2011 Nine films nominated.

Midnight in Paris. Letty Aronson and Stephen Tenebaum.

Moneyball. Michael De Luca, Rachael Horovitz, and Brad Pitt.

The Tree of Life. Sarah Green, Bill Pohlad, Dede Gardner, and Grant Hill.

War Horse. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Kennedy receives her sixth nomination.

The third year in which five women are nominated in this category.

The fifth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2012 Nine films nominated.

Amour. Margaret Mengoz, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz.

Django Unchained. Stacey Sher, Reginald Hudlin, and Pilar Savone.

Les Misérables. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Debra Hayward, and Cameron Mackintosh.

Lincoln. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Silver Linings Playbook. Donna Gigliotti, Bruce Cohen, and Jonathan Gordon.

Zero Dark Thirty. Mark Boal, Kathryn Bigelow, and Megan Ellison.

Eight female producers nominated, besting the previous record by three.

The first year in which each of two nominated films has two female producers.

Kennedy receives her seventh nomination.

2013 Nine films nominated.

12 Years a Slave. (WINNER) Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Klein, Steve McQueen, and Anthony Katugas.

American Hustle. Charles Roven, Richard Suckle, Megan Ellison, and Jonathan Gordan.

Dallas Buyers Club. Robbie Brennert and Rachel Winter.

Her. Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze, and Vincent Landay.

Philomena. Gabrielle Tana, Steve Coogan, and Tracey Seaward.

The Wolf of Wall Street. Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joey McFarland, and Emma Tillinger Koskoff.

Dede Gardner becomes the eighth woman to win an Oscar in this category.

Megan Ellison becomes the first woman nominated for two films in the same year.

2014 Eight films nominated.

Boyhood. Richard Linklater and Cathleen Sutherland.

The Imitation Game. Nora Grossman, Ido Wostrowskya, and Teddy Scharzman.

Selma. Christian Colson, Oprah Winfrey, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

The Theory of Everything. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce, and Anthony McCarten.

Whiplash. Jason Blum, Helen Estabrook, and David Lancaster.

2015 Eight films nominated.

Spotlight. (WINNER) Blye Pagon Faust, Steve Golin, Nicole Roaklin, and Michael Sugar.

The Big Short. Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, and Brad Pitt.

Bridge of Spies. Steven Spielberg, Marc Platt, and Kristie Macosko Krieger.

Brooklyn. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

The Revenant. Arnon Milchan, Steve Golin, Alejandro G. Iñárittu, Mary Parent, and Keith Redmon.

Blye Pagon Faust and Nicole Roaklin become the ninth and tenth winners.

For the first time two women win for the same film.

For the second time, two nominated films have two female producers.

2016 Eight films nominated.

Moonlight. (WINNER) Adela Romanski, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

Hell or High Water. Carla Haaken and Julie Yorn.

Hidden Figures. Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenro Topping, Pharrell Williams, and Theodore Melfi.

Lion. Emile Sherman, Iain Canning, and Angie Fielder.

Manchester by the Sea. Matt Damon, Kimberly Steward, Chris Moore, Lauren Beck, and Kevin J. Walsh.

Adela Romanski and Dede Gardner become the eleventh and twelfth winners.

For the second time, two women win for the same film.

For the second time, eight women are nominated, which so far remains the record.

Why should these names be hidden?

So we have overall 88 nominations for women, with twelve women winning Oscars for producing films. That compares with four nominations and one win for female directors. Women have not come all that close to parity with men in the producing category, but compared to the directors category, which people seem to take as a bellwether for the status of professional women in Hollywood, it’s spectacular. Moreover, we can see a fairly steady growth over the past twenty-three years, to the point where seven or eight producing nominations a year routinely go to women.

Of course, Oscars are not the only or the most objective way of measuring women’s power in Hollywood. One could try a similar examination of the number of women producing Hollywood’s top box-office films over the years. I assume there would be a similar growth in numbers, but the measurement would probably be a little more nuanced. That would be a much bigger project than would fit in a blog entry–even entries as long as the ones we occasionally favor our readers with. The San Diego State University study I mentioned earlier took an approach of this sort, and I’m sure there is deeper digging to be done among the statistics revealed by such research..

Given the way the Oscars have captured the public’s and the industry’s imaginations, however, the growing number of female producers being honored is a good way to point out that things may be better than they seem when one focuses narrowly on the directors category.

After all, the prescription for putting more women in the director’s chair and behind the camera and so forth is always that more female producers and writers are needed, making films for women and by women. This seems reasonable, and yet the question remains, if women are doing so well, relatively speaking, in rising to the top as producers, why, over the twenty-three years since 1994 haven’t they hired more women at every level for their film crews? (Of course, some of them have acted as producer-directors on their own projects.) Why hasn’t Kennedy, who has been firing and hiring male directors for Star Wars projects lately, ever given a female director a shot at it? Maybe she will at some point, as the evidence grows that women can create hits.

Perhaps most women producers are constrained by their fellow producers on projects, who are often men. They may feel pressured to reassure studio stockholders and financiers by sticking with the tried and true. And yet there do finally seem to be signs that studios are looking beyond the obvious pool of talent. Patty Jenkins, an indie filmmaker, directs Wonder Woman to unexpected success. Taika Waititi, a Maori-Jewish indie filmmaker from New Zealand, suddenly finds himself directing Thor: Ragnarok, which shows every sign of becoming a hit. With luck, the effect of the rise of female producers, as well as of more broadminded male ones, will finally have a significant impact on both gender and ethnic diversity in Hollywood filmmaking.

In closing, I would suggest to the press that it would be helpful for them in writing their endless awards coverage to list more than just the titles of the Best Picture nominees. Add the names of their producers, who are in effect nominated for Oscars. Treat them more like stars, the way you do with directors. I realize that there are often lingering disputes over which of the many producers attached to some films are actually the ones eligible to accept Oscars for them. But once such disputes are resolved, these “nominees” should be listed, and certainly after the awards are given out, they should be part of the historical record of Oscar nominees and winners. This would help both the public and the industry to get the big picture, not just the Best Picture.

[Oct. 24, 2017: My thanks to Peter Nellhaus for pointing out Julia Phillips’ win for The Sting in 1973. I have corrected the text accordingly.]

The Shawkshank Redemption (1994).