Archive for 2017

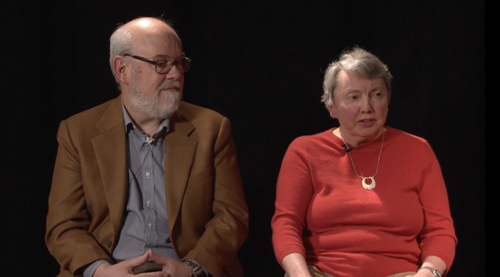

We do film, dammit: Charlie Keil interviews us

DB here:

The Society of Cinema and Media Studies has established an online series of interviews with film scholars. In these conversations, distinguished contributors to academic film history, theory, and criticism review their careers and sum up their main ideas.

Thanks to Charlie Keil’s initiative, we participated in one such session here at Madison, back in May. The result is here.

Under Charlie’s guidance we discuss how we got interested in studying film, how we conceived and wrote Film Art: An Introduction, and how we developed later research projects, including The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Narration in the Fiction Film, Breaking the Glass Armor, Making Meaning, The Frodo Franchise, and other books.

We talk about “neoformalism” and its relation to continental structuralism, as well as strategies of film analysis, the importance of norms, the roles of institutions in shaping film history, and cognitive film theory. We touch on the history of Wisconsin film studies and the central role of Tino Balio, Douglas Gomery, and Janet Staiger in shaping our thinking. We also talk about “overachieving” textbooks and our efforts to reach out beyond academic readers, especially via the Net.

Charlie skillfully fits what we tried to do into broader trends in academic film studies. He highlights our frequent returns to studying Hollywood as an artistic and industrial reference point. He even brings up Kristin’s Egyptological research.

There wasn’t enough time to survey all our interests, of course. There’s probably too little on our most recent work; if you want to dig more into our ideas, the published work and our writing on the blog are more informative. And there aren’t enough jokes, at least deliberate ones. Still, we hope some of you will find this discussion of interest.

Thanks not only to Charlie Keil and the SCMS people coordinating the Fieldnotes series, but also to Madison’s own Eric Hoyt, Chelsea McCracken, and Erica Moulton for shooting the interview.

Ritrovato 2017: Many faces, many places

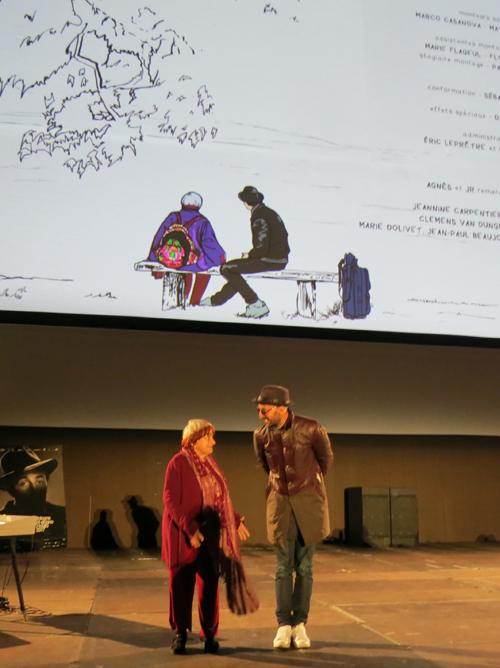

Agnès Varda and JR, Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 July. Photo: DB.

DB here:

This final post from Il Cinema Ritrovato is no less a miscellany than the others. With over 500 films screened, Kristin and I invariably missed things that others raved about. Still, we saw enough powerful cinema to make us want to flag some key items for you.

Silents, please

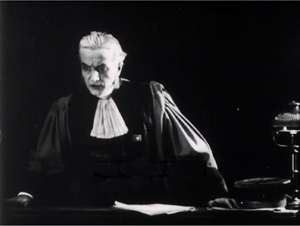

Kristin has already mentioned one of the most startling items we saw, Le Coupable (1917) by André Antoine. I’m still processing the audacity of this film. The prosecutor in a murder trial abruptly claims the defendant as his son. We then get the familiar flashback format, shifting from the courtroom to the events leading up to the crime and the arrest. But the shifts between present and past are so quick, and the bits we see of the trial are given in such intense, stark singles, that they gain an astonishingly modern pulse.

Add in marvelous use of locations, real alleys and corridors and cafes, and you have a very impressive movie.

Once more, 1917 proves to be dynamite.

From the same year came Furcht (Fear), by Robert Wiene. Count Grevin wanders anxiously through his castle for about sixteen minutes of screen time before we realize, thanks to a flashback, that he’s haunted by his theft of a precious Indian statue, stolen from a temple. Soon a priest materializes, either on the castle grounds or in Grevin’s imagination, to declare that he has only seven years to enjoy life before vengeance strikes. Which it does, of course. Conrad Veidt plays the priest with the smoldering glare, and ambitious superimpositions show how committed German cinema was to special effects. Dr. Caligari was three years off.

Not that other years should be slighted. Le Collier de la danseuse (The Dancer’s Necklace, 1912) was an agreeably preposterous crime movie. (The thief has a jacket with fake hands dangling from the sleeves, just the thing for escaping handcuffs.) The film boasted the low, almost Ozuesque, camera height typical of other Pathé productions of the year.

Not that other years should be slighted. Le Collier de la danseuse (The Dancer’s Necklace, 1912) was an agreeably preposterous crime movie. (The thief has a jacket with fake hands dangling from the sleeves, just the thing for escaping handcuffs.) The film boasted the low, almost Ozuesque, camera height typical of other Pathé productions of the year.

Borzage’s Secrets (1924) traces a marriage through three large flashbacks, with the first emphasizing romantic comedy, the second suspense, and the third family melodrama. Norma Talmadge, who savored a split-personality role in De Luxe Annie (1918), gets to play a woman at three ages here. The central section, devoted to a Griffithian siege on a lonely frontier cabin, showed Borzage’s ability to whip up enormous excitement, with an unexpectedly sad twist. The whole movie has over 11oo shots, indicating just how committed American filmmakers had become to fine-grained scene breakdowns.

All in all, the silent films on display this year were as revelatory as ever.

Cinematic geometries

The Abe Clan (1938).

For some years Ritrovato has included a Japanese sidebar curated by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström. This year the theme was socially critical jidai-geki, or historical films. Some of them were fairly familiar to Western cinephiles because copies were circulated by the Japan Film Library Council from the 1970s onward. Examples include The Abe Clan (1938) and Fallen Blossoms (1938), both very good films. Along with these, the Bologna series gave the Yamanaka Sadao classic Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937) another well-deserved airing.

Some of these are fairly intimate dramas, others use a lot of spectacle. The image from Abe Clan above is fairly typical of the monumental turn some jidai-geki took in the late 1930s. Several of the films starred members of the left-wing Zenshinza kabuki troupe, perhaps best known to aficionados from Mizoguchi’s staggering Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942).

Three of the other films showed the range of this genre during Japan’s “dark valley,” its turn to authoritarian rule and imperial warfare. The Rise of Bandits (1937), by Takizawa Eisuke, was a rousing but melancholy Robin Hood tale. A lord’s honest son tries to save a shipment of gold from marauders, but he’s framed by his duplicitous brother. So he becomes the outlaws’ leader, at the cost of his wife’s life and his father’s trust. Some superb action sequences, including a fiery final assault on the castle, alternate with semicomic scenes among the bandits, with the hero’s cynical sidekick twisting not-too-bright thugs around his finger.

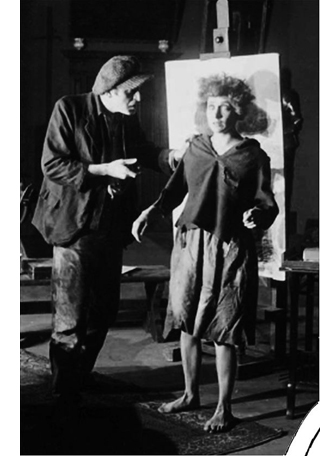

Hagiwara Ryo’s The Night Before (1939, production still above) was based on a Yamanaka script, and like Humanity and Paper Balloons, it braids together several characters’ fates. As rival samurai factions struggle during the Meiji restoration, ordinary people–an artist, a family running an inn, a young man wanting to make his name as a warrior, a bitter and disenchanted samurai–try to get by. One of the innkeeper’s daughters is attracted to the youth, another daughter who works as a geisha eyes the artist, and the old man seems to escape into endless games of shogi with a neighbor. The film has a panic-stricken climax, in which the factions collide in darkness along the riverside and innocents get swept up in the violence. As with many films in the series, the critique of mindless militarism isn’t far below the surface.

The Man Who Disappeared Yesterday (1941), by the great Masahiro Makino, is a murder mystery. An unpleasant landlord is the victim, and there are plenty of suspects. The scattered clues didn’t seem to me to play entirely fair, but the investigation is largely a pretext to explore adjacent households and obfuscate what turns out to be complicated post-murder maneuvers. At the climax, all the suspects are seated in a single line to hear the magistrate’s solution, just as if they were in Nero Wolfe’s office.

Makino’s style accentuates the spatial layout through a remarkable ten zoom-ins that yank us to one or another suspect as the explanation is given, sometimes with flashbacks. Camera zooms (as opposed to optical-printer ones, as in Citizen Kane) are rare in any national cinema of this period, and Makino uses them almost in the spirit of Hong Sangsoo, more to perk up our attention than to enlarge anything for closer scrutiny. (Admittedly, the last one rivets us on the guilty party.) The same geometrical impulse encloses the tale: an opening crane shot down, a closing one upward. As often in Japanese cinema, The Man Who Disappeared Yesterday marks and repeats film techniques to give a decorative flourish to the story.

Technique also comes to the fore, of course, in Divine (1935), a French production directed by Max Ophüls. The attraction isn’t just the dizzying camera movements, swimming through a tangle of backstage paraphernalia and crawling up stairways. Max is more than a master of the tracking shot. In one witty passage, framing and cutting coordinate to stretch the distance between a couple who can’t tear themselves away from each other. (In my last frame, the milkman’s head slides almost out of frame.)

The plot centers on a country girl who becomes a follies performer and is framed as a drug dealer by a Lothario and a lesbian. This contraption seems more or less a pretext for Ophüls to indulge his endless fascination with women striking poses for men while asserting their own demands. The abrupt and unexplained happy ending is the logical wrapup for a film less concerned with a plausible plot than a display of Woman in all her dazzling divinity. There. How’s that for a Sarris sentence?

Bigger than life

Although there were some repeats on Sunday, the final big event of the festival was the screening, to some 3000 people on the Piazza Maggiore, of the new film by Agnès Varda and JR. Kelley Conway reviewed its Cannes premiere for us earlier, and now that we’ve seen it, we like it a lot.

Varda has the ability to take a whimsical, borderline-cutesy idea and turn it into something poignant, as in Daguerreotypes and Opéra-mouffe. (Nursery-rhyming titles, like Mur Murs and Sans toit ni loi, encapsulate her attitude.) Her latest, an associational documentary along the lines of The Gleaners and I, depends on the premise of traveling through France and making enormous photographic portraits of ordinary people. These are then mounted on buildings in their home town–hence the title Visages Villages.

The result is both intimate and monumental. A postal clerk or a woman truck driver take on the billboard proportions of politicians and pop stars. Without any sense of slumming, Varda and JR can memorialize a woman living in a building about to be demolished, and can spare time for a haggard hermit who has dropped out of the system. It’s as powerful a populism as any you’ll see, but done with humor, genuine curiosity, and respect for the integrity of each subject. A playful approach to art can yield serious emotional effect.

As Visages Villages goes on, it turns introspective. Varda recalls episodes from her life and tries to incorporate one of her photos, a casual shot of Guy Bourdin, into a skewed tipsy WWII bunker rusting on a beach. She recalls young days with Godard and Karina, so that now when Godard dodges a meeting, she becomes rueful (“The rat!”). This lady gleaner is always gathering fragments, and we’re lucky she shares them with us.

Again Bologna gave excellent, overwhelming value. The surprises never stopped. Dropping into a film I hadn’t seen in three decades, Rancho Notorious, I not only had fun but realized once more Lang’s diabolical genius. A peculiar insert of a boot slipped into a stirrup puzzled me, but after an hour I got it. (Forgive me, Fritzie, for I knew not what I did.) Long may this festival flourish.

Thanks as ever to the vast and dedicated staff of Il Cinema Ritrovato, particularly Guy Borlée, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Mariann Lewinsky.

I discuss the trend toward monumental jidai-geki in chapters 12 and 15 of Poetics of Cinema. More detailed analysis can be found in Darrell William Davis’s book Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Cinema.

Visages Villages (aka Faces, Places) is distributed by the Cohen Media Group.

Agnés Varda and JR. Photo: DB.

Ritrovato 2017: An embarrassment of riches

Place de la Concorde (somewhere between 1888 and 1904)

KT here:

David’s recent entry stressed the world-wide scope of offerings here at Il Cinema Ritrovato. The time period covered is even broader–this year as broad as it could possibly be. The final night’s film in the Piazza Maggiorre will be Agnès Varda and JR’s prize-winning documentary straight from this year’s Cannes festival, Visages Villages, with Varda here to introduce it. Yesterday we saw a work that may have been created before the cinema itself had been properly invented.

The earliest years

Somewhere in the time period 1888 to 1904, French scientist Etiennes-Jules Marey created a huge photographic format, a filmstrip 88 mm wide and 31 mm high. He exposed a series of images along this broad strip but never intended to project them as a film. As with much of Marey’s work, these high-quality photographs were tools to allow him to analyze movements, in this case those of humans and horses in the Place de la Concorde.

The National Technical Museum in Prague has scanned this series of frames to create a digital copy that can be projected in motion. The results, lasting only 45 seconds, has a clarity and detail that seems to rival that of Imax film. (The image at the top only hints at the effect.) We watched the piece four times and would have been glad to see it at least as many more.

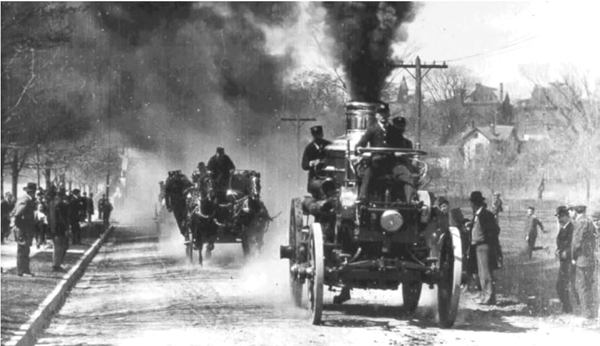

A major thread running through the festival is the year 1897, which, although only the second year of the established film industry, already saw the making of many beautiful and intriguing films. Among the ones shown here were films made by the American Mutoscope Company (later known under the more familiar name, American Mutoscope and Biograph) and British Mutoscope and Biograph. These films, made to be shown in both peepshow machines and projected onto screens, utilized a 68 mm format.

Such films have mainly been seen in poor prints that give an impression of primitive crudeness. Thanks to preservation work on collections in the EYE Filmmuseum and the BFI-National Archive, the richness and clarity of these films have become evident, and they look anything but primitive. One American film (above) is Jumbo, Horseless Fire Engine, credited to William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson himself, provides what must have been an exciting variant on the many films featuring horse-drawn fire engines racing along streets.

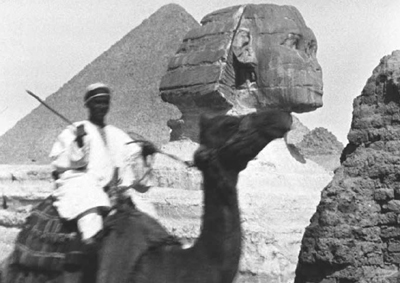

One of the Lumière company’s most prolific traveling cameramen was Alexandre Promio. I was naturally intrigued by series he filmed in Egypt in 1897. One thing that struck me about 28 films in the program was how few featured famous tourist attractions and truly picturesque images. True, Les Pyramides (vue générale) shows one of the most familiar ancient sites in the world, the Sphinx against the great pyramid of Khufu.

Most of the rest of these brief films are remarkably mundane, however. Place de la Citadelle shows an open space with a nondescript building in the distance rather than the two main attractions of the Citadel, the Mosque of Mohammed Ali and the spectacular view out over the city. Village de Sakkarah (cavaliers sur ânes) shows fellahin riding donkeys in modern Mit Rahina, but in the background the colossal quartzite statue of Ramesses II lies on the ground (where it still lies today, covered by a shelter). It is a beautiful statue, visited by nearly all tourists, and yet in the film it is merely a distant, vague shape, identifiable only to those who are familiar with it.

Numerous other views are moving, taken either from trains and showing ordinary industrial buildings or from boats, showing mainly palm trees. The collection leads one to speculate what prompted Promio to choose his subjects.

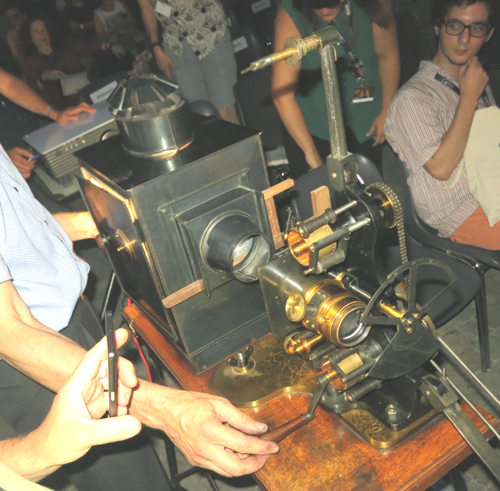

I believe the tradition of showing films in the open air of the Piazzetta Pier Paolo Pasolini (the courtyard of the Cineteca di Bologna) on carbon-arc projectors began in 2013, which I reported on it. This popular feature has expanded, with three programs this year. The first centered around Addio, Giovenezza!, which David described in his entry. The second was particularly special, with a five early shorts ranging from 1902 to 1907 shown on a vintage 1900 projector, hand-cranked by Nikolaus Wostry of the Filmarchiv Austria. The films were charming, but the star of the show was the projector. It looked like a magic lantern dressed up with special attachments that allowed for moving pictures, including a shutter sitting in front of the lens rather than within the body of the lantern. Indeed, the thing looks like a magic lantern converted into a film projector.

This projector cast a much smaller image than the later carbon-arc projector used for the second part of the show. The image had rounded corners and it flickered distinctly. At times, despite Wostry’s obvious expertise at hand-cranking, the image would briefly go to black. Watching this presentation, it became easy to grasp how early audiences might have been constantly aware of the artifice, the machine, creating these images and have marveled at any sort of moving photographs that were cast on the screen before them. It was a magical few minutes, making almost real the section of the program entitled “The Time Machine.”

Classics of 1917

Although there was some thought of ending the Cento Anni Fa programs once the feature film became established, that has fortunately not been done. Instead, a mixture of shorts and features continues to celebrate the cinema of a century ago. Some of the Italian films David wrote about came from that year.

I had the chance to see two masterpieces from that year back to back: André Antoine’s Le coupable and Victor Sjöström’s The Girl from Stormycroft. Both center around the subject of women seduced and left pregnant by their selfish lovers.

I had never seen Le coupable. Antoine is often referred to as a naturalist theatrical director, but going by Le coupable and La terre (1921), he is equally a major film director in the realist tradition, though his output consisted of only nine films from the brief period 1917 to 1922.

While La terre was filmed largely in the countryside, Le coupable was shot in the streets of Paris, and many of its interiors seem to be set in real rooms. Antoine manages to combine the gritty realism of his lower-class milieux with beautiful cinematography (see bottom image). The story takes the unusual form (for its day) of a lengthy series of flashbacks framed by a trial of a young thief and murderer. The past does not unroll from witnesses’ testimony, however, but from one of the presiding judges’ lengthy confession that he is the father of the accused and had abandoned the boy’s mother. The situation is pure melodrama, but Antoine’s light touch and feel for the settings of the action make it a masterpiece.

The Girl from Stormycroft has the distinction of being the first adaptation of a novel by internationally popular author Selma Lagerlöf, whose work was to be the basis for several classics of the Swedish silent cinema, including The Phantom Carriage and Stiller’s The Saga of Gõsta Berling (1924). It is set in the countryside, in a group of small villages. Helga, the heroine, has been seduced by a married man who refuses to acknowledge her child as his own. In a key trial scene, she gives up her suit against him to prevent his committing a sin by swearing to a lie on the Bible. This gains the admiration of a well-off and kind young man, Gudmund, who persuades his mother to take Helga on as a maid. When his fiancée and her parents visit Gudmund’s family, they express disgust at her presence and depart (above), leaving Gudmund is left with doubts about his upcoming marriage.

Early sound films

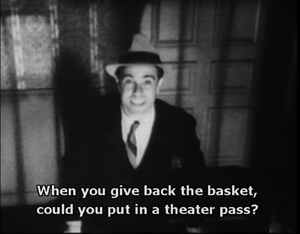

Il Cinema Ritrovato’s programs offer an opportunity to sample early sound films from a much wider range of countries than usual. Gustav Machaty, best known for Ecstasy (1933), made From Saturday to Sunday in 1931. It follows a pair of working girls who go out to a ritzy nightclub with two wealthy men, intending to exploit the two for a lavish night out while avoiding their sexual demands.

This proves more difficult than they expected, and we end up following one of the pair as she is stranded late at night in the pouring rain. As the title suggests, the action is a slice of life, lasting less than 24 hours. Machaty manages to blend the visual style of the late 1920s with a firm grasp of sound technology. The result is an entertaining if rather conventional tale.

Mexican filmmakers seem to have proved equally adept at taking up sound. The program notes for the program “Rivoluzione e avventura: Il Cinema Messicano dell-Epoca d’Oro” point out that Mexican production burgeoned in the 1930s, going from one feature in 1931 to 21 in 1933.

The earliest film in this thread, El Compadre Mendoza (1933), is a technically and stylistically impressive film, looking like a Hollywood film of the same era. It’s part of a trilogy about the Mexican Revolution, coming between director Fernando de Fuentes’ El prisionero 13 (1933) and Vámonos con Pancho Villa (1935), though it is quite comprehensible and enjoyable on its own.

The irony of the title is that the protagonist, a jovial, sociable plantation owner, is professing loyalty to both sides, and for years he manages to live a pleasant life with his family and staff on their large hacienda. The film is remarkable in portraying the Revolution almost entirely offscreen. The narrative sticks mostly to Mendoza’s house, and we gauge the progress of the fighting purely through a series of sequences in which either revolutionary or government troops ride up the long, tree-lined road to the house. There Mendoza and his household provide a bit of socializing, putting up an effective façade of loyalty to whichever army is present at the time.

Mendoza develops a particular friendship with Felipe, a Revolutionary general (above), who also attracts Mendoza’s young wife in what develops into a lengthy unconsummated romance. Inevitably Mendoza’s juggling of the two sides collapses as he is forced to help one of them against his will.

For me the most unexpected discovery of the festival was the second Mexican film, Two Monks (1934). It is considered the first in the Mexican Gothic genre. It was inspired by the Spanish-language version of Dracula (directed in 1931 by George Melford for Universal), as well as by German Expressionist films.

There are no monsters in the film. Instead, a frame story set in a monastery that looks straight out of Murnau’s Faust (1926) introduces a young monk, Javier, who has gone mad. He attacks another monk, Juan, with a crucifix and confesses to the prior that he did so because Juan had committed a terrible crime. A lengthy flashback lays out the story of Javier’s love for Ana and his eventual rivalry with Juan. In the second half, Juan also confesses, and the story is repeated from his point of view. Scenes we saw earlier are replayed, often starting at an earlier point or ending at a later one, in a way that alters our understanding of the two monks’ past relationship. The result is not a Rashomon-type situation, for the two men agree on the events they describe, disagreeing only on the implications of those events.

It’s a remarkable narrational technique for this early in film history. The atmospheric claustrophobia created by the small cast (no passers-by are seen in the brief street scenes and no servants appear in the houses) and of dread created by the sets and the dissonant music of the climactic scene would bear comparison with the horror films of Universal and Hammer.

Restorations that make me feel old

Film restoration has been around for decades, but at some point within the several years I noticed that an increasing number of films were being restored were ones that I had seen when they first came out or shortly thereafter. Modern classics restoration wasn’t just for silent films and movies from the golden studio era. Now they’re for modern classics: The Graduate, Belle du jour, Women in Love, Blow-Up, and Day for Night (not to mention the restorations shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in past years).

My first thought is, why do such recent films need restoration? Answer: maybe they’re not as recent as they seem to me. My second thought is, haven’t the studios realized that they need to take care of their films? Answer: Yes, to some extent, given the vital work done by studio archivists like Grover Crisp and Shawn Belston. Still, will There Will Be Blood be neglected until it needs restoration in twenty years’ time?

My first thought is, why do such recent films need restoration? Answer: maybe they’re not as recent as they seem to me. My second thought is, haven’t the studios realized that they need to take care of their films? Answer: Yes, to some extent, given the vital work done by studio archivists like Grover Crisp and Shawn Belston. Still, will There Will Be Blood be neglected until it needs restoration in twenty years’ time?

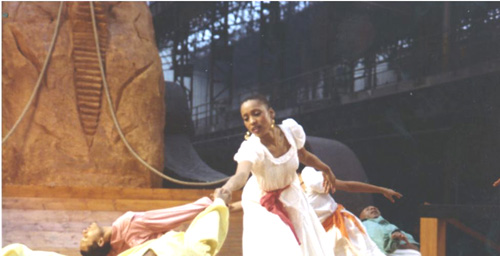

Among the relatively recent films presented in restoration here is Med Hondo’s West Indies (1979). The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project undertook to restore a number of films by Hondo, a Mauritanian actor and director and one of the most important directors from the African continent.

West Indies is a remarkable film, a musical on the history of French slave-owning in its Caribbean colonies. Inside an empty factory Hondo built a large set depicting the upper and lower decks of a slave ship. The various sections of this ship provide stages upon which scenes, anything from a 1968 demonstration in the streets of Paris to a slave auction hundreds of years before. Five actors representing colonial interests, including a black man who cooperates in order to maintain his position as a figurehead governor, take similar roles throughout the action.

It’s a lively, entertaining film, done in color and widescreen, as well as a maddening look at French complacency and casual cruelty. Most of the musical numbers are dances rather than songs, with Hondo himself having choreographed several of them.

Hondo, now 81 and reportedly seeking backing for another film, was present at the festival and introduced the screening of West Indies that we attended. He was visibly moved by the chance to show this little-known work to an appreciative audience and thoroughly won us over during his brief presentation. With luck we will see a tenth film from him.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for his assistance with this blog, and to the programmers and staff of Ritrovato for another dazzling year. You can download the entire festival catalogue here.

Kelley Conway reviewed Visages Villages at Cannes for our blog.

Le coupable (1917)

Ritrovato 2017: Drinking from the firehose

DB here:

Immense scale and teeming activity are nothing new to Il Cinema Ritrovato, the Cineteca di Bologna’s annual jamboree of restored and rediscovered films from all over the world. The scorching heat–90 degrees and more for the first few days–only makes it seem more intense than usual.

Kristin and I had to miss the last Ritrovato session, but we’re convinced that this nine days’ wonder is still the film-history equivalent of Cannes.

In one way, your choice is simple. You can follow one or two threads–say, the Robert Mitchum retrospective or the Collette and cinema one or the classic Mexican one, or whatever–and dig deep into that. Or you can skip among many, sampling several, smorgasbord-style.

In practice, I think most Ritrovatoians pursue a mixed strategy. Settle down one day for a string of, say, early Universal talkies and another day check out the restored color items. On off-days roam freely. The problem is you will always, always miss something you would otherwise kill to see.

At the start, I plumped for 1910s films, particularly Mariann Lewinsky’s reliable 100 Years Ago cycle. My other must was the Japanese films from the 1930s; half of the titles brought by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, were new to me. As of this writing, I haven’t seen those, but I have dug into the 1917 items. And I indulged myself with, no surprise, some gorgeous Hollywood things.

1917 and all that

Malombra (1917).

If you caught any of my dispatches from Washington DC earlier this year (starting here) you know I was burrowing deep into American features of the 1910s That complemented several years of archival work on European films of the same period. So of course the chance to sample 1917 features from Hungary, Poland, Russia, and elsewhere was not to be passed up.

Some superb ‘teens films I just skipped through familiarity. Gance’s Mater Dolorosa (1917), possibly the most patriarchal film in the thread, remains tremendously inventive at the level of silhouette lighting and continuity cutting (a huge variety of camera setups during the fatal love tryst). And one of the very greatest directors of the period, Yegenii Bauer, was represented by two of his last films, The Revolutionary and Towards Happiness. I’ve studied both elsewhere, in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and online. Even so, I found plenty to keep me busy.

One of the main threads was devoted to Augusto Genina, a director with an astonishingly long and prolific career. Probably best known for Prix de Beauté (Miss Europe, 1930), he started in 1913 and made his last film in 1955. His 1910s films confirm that Italy was producing many films of striking beauty and audacity in those years.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

In a similar vein is Addio, Giovenezza! (1918), adapted from a popular song. This one, screened in an open-air venue thanks to an arc-lamp projector, is another sad Genina tale. A careerist law student abandons his rooming-house maid for a social butterfly with a wardrobe to die for. Apart from one startling scene in a milliner’s shop, illuminated mostly by spill from the street, the lighting isn’t as daring as in Lucciola. Still, the poignant plot is again inflected by comic touches, proceeding largely from the hero’s nerdish fellow student. Genina redid the story again in 1927, and I’m hoping to catch that screening.

Malombra (1917), starring the diva Lyda Borelli, was by the great Carmine Gallone. (I’ve discussed La Donna nuda and Maman poupée hereabouts.) After moving into a castle, Marina becomes possessed by the spirit of the woman who died there. Our heroine’s job is to take revenge on the faithless husband. Flirtatious and iron-willed, Borelli dominates her scenes with shifts of stance, sudden freezes, rapid changes of expression, languorous arm movements, and, at one climax, a swift undoing of her hair that lets it all tumble wildly around her face. The print, needless to say, was superb.

In a lighter vein, if you wanted proof of the inventiveness of ‘teens Italian film, you couldn’t do better than Wives and Oranges (Le Mogli e le arance; 1917). This agreeably silly movie sends a bored young man to a spa populated by incredibly aged parents and a bevy of scampering daughters. With an avuncular friend, Marcello capers with the girls before settling on the most modest one as his wife. But her friends aren’t disappointed because our hero’s pals come for a visit and get roped into matrimony too.

Wives and Oranges has a remarkable freedom of narration. The film uses montage sequences with a fluidity that is rare at the time. To convey the boredom of Marcello’s daily routine, a string of quick shots is punctuated by changing clock faces. Later, the idea of finding one’s ideal love mate by matching halves of oranges is presented via an absurd montage of old folks, youngsters, babies, and just abstract hands, all wielding oranges.

Marcello’s paralyzing dilemma of choice is given as a nondiegetic insert of a donkey unable to decide between a hay bale and a bucket of water. These flashy devices keep us interested in a situation that, in script terms, is probably stretched too thin–although when things slow down you can count on the daughters forming a chorus line and zigzagging down the road or popping out from under the dinner table one by one.

Almost as lightweight was The War and Momi’s Dream (La Guerra e il sogno di Momi, 1917), by the great Segundo de Chomón, who moved among France, Spain, and Italy making fantasy films of many types. This one is largely meticulous puppet animation, in which a boy’s toys come to life and enact–at the height of the World War–their own combat.

Trick and Track marshall other toys to play out some seriocomic clashes, including a burning farmhouse and one astonishing shot of an entire town landscape, covered in a long camera movement. Again, there’s no underestimating the sheer technical audacity of Italian cinema of these days.

There’s always an exception, of course. The late David Shepard left us, among much else, Shepard’s Law of Film Survival: The better the print, the worse the movie. A good example is La Tragica fine di Caligula Imperator (1917), signed by Ugo Falena. It’s surprisingly retrograde for an Italian film of the period. Neither the staging (flat, distant) nor the cutting (minimal) nor the lighting (little modeling) is much in tune with contemporary norms. The problem may be the immense sets, which are indeed impressive but which seem to encourage the actors to a hard-sell technique.

The most amped-up is Caligula himself. Playing a mad Roman emperor often tempts any actor to gnaw table legs. But as an example of what a silent film really could look like, Caligula should be required viewing for anybody who sneers at Those Old Movies. If Christopher Nolan saw it, he’d demand to shoot on orthochrome nitrate.

Other 1917 features included The Soldier on Leave, from Hungary, and Stop Shedding Blood!, by the great Russian director Jakov Protazanov. The former was restored from a 17.5mm copy, the latter was missing the two central reels. The Protazanov in particular had some sharp staging in depth and rich sets.

In the same batch was Pola Negri’s screen debut in Bestia (1917, imported to the US as The Polish Dancer). In a fine copy, you could appreciate the bouncy but sultry screen presence that made her a star. And as often happens with films from anywhere in this period, the sets sometimes play peekaboo with the action. Pola, after a night out with her thuggish lover, sneaks back to her bed while her father snores in the background, caught in a slice of space.

Back in the USA

Kid Boots (1917).

The 1917 American entry was a strong, unpretentious Western by Frank Borzage, Until They Get Me. It’s missing some scenes in the middle, but it remains a forcefully quiet movie. The only gunplay takes place at the start, when a man racing to get to his wife in childbirth is forced into a gunfight. He kills the drunkard who provoked it, but by the time he reaches his home, his wife is dead. Now he must flee Selwyn, a mountie. Stealing a horse, he picks up an orphan girl fleeing an oppressive household. The rest of the film will intertwine the fates of the three, leading to a surprisingly civilized resolution.

Borzage is one of the many great directors–De Mille, Dwan, Walsh, Ford, Brown, King, Barker–who started doing features in the mid-teens. Most had long careers. They mastered the emerging norms of Hollywood continuity cinema and learned to deploy them with tact and precision. Just the timing of the reaction shots in Until They Get Me is worth study.

Frank Tuttle started in features a bit later, in 1922, but Kid Boots (1926), my first movie of the Ritrovato, showed complete mastery of comic storytelling. Eddie Cantor, a fired tailor, becomes amanuensis to Tom Sterling, a man-about-town in the throes of a divorce. The twist is that his wife, learning of Tom’s new inheritance, wants to halt the divorce by sharing his bed again. Eddie’s job is to keep the wife and the lawyers at bay until the divorce becomes final. Into this tangle plops perky Clara Bow in her first film after her breakout role in Mantrap (also 1926). You could watch her cock her chin and roll her eyes for hours. She steals the picture from Billie Dove.

The gag situations come thick and fast, with one high point being Eddie’s efforts to get Clara jealous by recruiting a strategically open door to help him pretend that his left arm actually belongs to Tom’s seductive wife. The whole thing culminates in a breathless chase on horses along a treacherous mountain pass. Eddie and all the others keep things lively, and Tuttle’s direction is exacting.

I strayed from the ‘teens again at Dave Kehr’s urging. Of Dave’s magnificent MoMA restorations, I caught William K. Howard’s Sherlock Holmes (1932). Apart from a wild-eyed Ernest Thesiger and an imperturbable Clive Brook, it boasts an abstract opening of silhouettes and confrontational close-ups and a conclusion of percussive flashes as Moriarty’s gang torches its way into a bank.

Ace cinematographer George Barnes had a field day with this one.

That was followed by Tay Garnett’s Destination Unknown (1933), a tense drama of a crisis on a bootlegging ship immobile on a windless sea. Hard, fast playing by Pat O’Brien and Alan Hale was offset by the leisurely presence of none other than Ralph Bellamy, aka Jesus of Nazareth. Don’t ask; just see it.

More from me, and Kristin, later in the week.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for a great deal of assistance on this entry. Thanks as well to the programmers and staff of the festival, especially Gian Luca Farinelli and Mariann Lewinsky.

The Ritrovato site is constantly updated. For our earlier Ritrovato communiqués, go here.

Malombra (1917; production still).