Archive for January 2018

Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry

DB here:

It’s a commonplace of film history that under Stalin (a name much in American news these days) the USSR forged a mass propaganda cinema. In order for Lenin’s “most important art” to transform society, cinema fell under central control. Between 1930 and 1953 a tightly coordinated bureaucracy shaped every script and shot and line of dialogue, while Stalin frowned from above. The 150 million Soviet citizens were exposed to scores of films pushing the party line.

True? Not quite.

When cows read newspapers

The Miracle Worker (1936).

In the film division of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, we’ve developed a reputation for revisionism. We like to probe received stories and traditional assumptions. In Soviet film studies, Vance Kepley’s In the Service of the State challenged the idealized portrait of Alexandr Dovzhenko, pastoral poet of Ukrainian film, by tracing his debts to official ideology. In my book on Eisenstein, I suggested that this prototypical Constructivist opens up a side of modernism that is artistically eclectic, and even conservative in its gleeful appropriation of old traditions.

Now we have a new book telling a fresh story. Maria (“Masha”) Belodubrovskaya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

Was this an ideological juggernaut? Aiming at a hundred features a year, the studios were lucky to release half that. In 1936 95 films were planned, but only 53 were produced and 34 made it to screens. From 1942 on, those millions of spectators saw only a couple of dozen annually. The nadir was 1951, with 9 releases. (Hollywood studios released over 300.) The flood of propaganda was more like a trickle. Theatres were forced to run old Tarzan movies.

When quantity became thin, apologists claimed that quality was the true goal. But Ninotchka’s hope for “fewer but better Russians” wasn’t realized in the film domain. Critics and insiders admitted that nearly all the films that struggled into release were mediocre or worse.

Not According to Plan shows that Soviet institutions were incapable, by their size, organization, and political commitments, of organizing a mass production film industry. Efforts to set up something like the U.S. studio system ran up against obstacles: there weren’t enough skilled workers, and decision-makers clung to the notion of the master director. Boris Shumyatsky, who visited Hollywood and tried to create something similar at home, got his reward at the muzzles of a firing squad. But brute force like this was rare; there were few administrators and creators to spare.

The great plan was to have a Plan—specifically, a thematic one. Production would be based on an annual cluster of powerful topics like “Communism vs. capitalism” and “Socialist upbringing of the young.” Personnel were slow to realize that themes were not stories, let alone gripping ones, and the real work of imagination remained un-plannable. Starting from themes rather than plot situations, the overseers could judge only final results, which meant enormous investments in development and production—all of which might never yield a politically correct movie.

Production, wholly divorced from distribution and exhibition, couldn’t count on the vertical integration of Hollywood. Masha shows in rich detail how policies and routines worked against large-scale output. One of the most striking of those policies was the veneration of directors. A great irony of the book is that Hollywood filmmaking, with its platoons of screenwriters both credited and uncredited, was more collectivist than production in the USSR. Soviet directors enjoyed enormous stature and power. They were often the moving force behind a production, bringing on writers and then recasting the script during shooting. Assemblies of directors formed review committees, discussing and often defending their peers’ work. As Masha puts it:

The filmmaking community, and specifically film directors, never gave up on the standard of artistic mastery. They listened to the signals sent by the Soviet leadership, but then incorporated these into their own professional value system, which developed in the 1920s outside the purview of the state. Using the state’s discourse of quality and their peer institutions, they enforced their own shared norms of artistic merit.

The downside of this system, plan or no plan, was that when the film didn’t pass muster, the director was to blame. Yet the twenty or so “master” directors could survive failed projects. New talent wasn’t trusted; there were too few directors; and most basically, the organization of production remained artisanal. The role of the producer (let alone the powerful producer) scarcely existed. To a surprising extent, Soviet cinema encouraged the director as auteur. How’s that for revisionism?

Screenwriters weren’t as powerful, but they did their part. Masha has a fascinating chapter on the changing conceptions of the Soviet screenplay. The “iron scenario,” modeled on a Hollywood shooting script, was intended to lay out the film in toto, so directors couldn’t overshoot or make changes. This initiative, predictably, failed. There followed other variants: the butter scenario, the margerine scenario, and the rubber scenario (no kidding), then the emotional scenario and the literary scenario.

Masha traces the work process of screenwriting and the mostly futile efforts of literary figures to leave their stamp on a production. A similar stress on process characterizes her occasionally hilarious case studies of censorship. Some of these expose the limits of industry self-censorship. One agency signs off on a film, the next one castigates it, the next one reverses that judgment, Pravda weighs in, and finally Stalin speaks up—with a completely unpredictable verdict, à la Trump. The tale of Medvedkin’s The Miracle Worker, which jumped through all the hoops and wound up being banned after initial screenings anyhow, might have been written by Zoshchenko or Ilf and Petrov. Among the elements judged “absolutely impermissible” were shots of cows reading newspapers.

The artistic and popular success of Soviet films during the New Economic Policy (1921-1928) had spurred hopes for a mass-market sound cinema that was also of high quality. What crushed that dream? Masha gives us the hows (the machinations of the studios and government bodies) and the whys (the underlying causes and rationales). Not According to Plan is a trailblazing study of what she calls “the institutional study of ideology.” It’s also a quietly witty account of the failures of managed culture. How could artists be engineers of human souls if they couldn’t engineer a movie?

But go back to the quality issue. What were those Stalinist films like artistically?

Socialist Formalism

Three projects I’ve undertaken led me to Stalin-era cinema. Nearly all English-language film histories ignored it, or reduced it to boy-loves-tractor musicals. So Kristin and I wanted our textbook Film History: An Introduction to consider it. (Revisionism again.) My Cinema of Eisenstein and On the History of Film Style built on what I saw at archives in Brussels, Munich, and Washington DC.

As a result I sought to mount an argument that Stalinist cinema was worth our attention, especially from the standpoint of film technique. The run-of-the-mill productions seemed fairly shambolic, but the top-tier dramas revealed an academic style that interested me. Some films recalled, even anticipated, innovations taking hold in Europe and America, but other creative choices were surprisingly offbeat, and not what we associate with standard propaganda.

For one thing, it was clear that montage experiments didn’t end with the 1920s, the arrival of sound, or even the “official” establishment of Socialist Realism around 1934. Granted, classic continuity editing rules the fiction films of the 1930s and 1940s, and the most flagrant extremes of the montage style were purged.

But some moments recall the silent era. These passages are typically motivated, as in Hollywood and other national traditions, by rapid action. Military combat calls forth stretches of 2-4 frame shots of bombardment in The Young Guard, Part 2 (1948). The combat scenes of The Battle of Stalingrad (1949) include very brief shots. In one passage, an artillery blast consists of three frames—one positive, a second negative, and a third positive again, creating a visual burst.

The abrupt disjunctions of the 1920s style can be felt a little in one cut of The Fall of Berlin (1950), when at the end of a long reverse tracking shot, Alyosha and his comrades rush the camera. Cut to Hitler recoiling, as if he sees them.

As you’d expect in an academic tradition, the use of fast cutting for fast action isn’t disruptive. A little more unusual is the embrace of wide-angle lenses, often more distorting than in Western cinema. Wide-angle imagery was used by 1920s filmmakers, often to caricature class enemies or to heroicize workers. The same sort of thing can be seen in Kutuzov (1945), when a soldier is presented in a looming close-up, or in Front (1943), when a gigantic hand reaches out for a telephone.

This use of wide angles to give figures massive bulk continued through the 1950s, as in The Cranes Are Flying (1957).

The 1940s aggressive wide-angle shots run parallel to Hollywood work, when in the wake of Citizen Kane (1941), The Little Foxes (1941), and other films, many directors and cinematographers created vivid compositions in depth. Those weren’t unprecedented in America, as I try to show in the style book, but there were some early adopters in Russia as well.

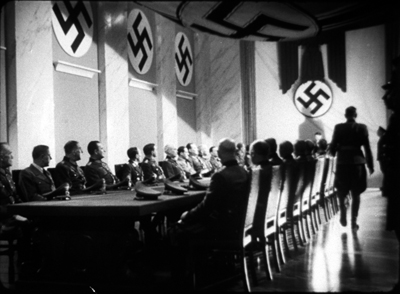

Obliged to show meetings of saboteurs, workers, generals, and party leaders, Soviet filmmakers had to dramatize people in rooms, talking at very great length. The result was a tendency toward depth staging and fairly long takes. The low-angle depth shot stretching through vast spaces became a hallmark of this academic style in the 1930s and after.

Director Fridrikh Ermler, one of the few directors who was a Party member, claimed that he devised a “conversational cinema” to deal with the prolix dialogue scenes in The Great Citizen (1937, 1939). The movie teems with shots that wouldn’t look out of place in American cinema of the 1940s.

As a solution to the problem of talky scenes, staging of this sort makes sense as a way to achieve some visual variety, and to show off production values. By the 1940s, such flamboyant depth became even more exaggerated. We see it in the telephone framing from Front above, as well as in The Young Guard Part 1 (1948, below left) and the noirish stretches of The Vow (1946, below right).

The Fall of Berlin can use depth to contrast the placid self-assurance of Stalin with a ranting Hitler, bowled over by his globe. Is this a reference to the globe ballet in The Great Dictator?

It’s well-known that for Kane Orson Welles and Gregg Toland wanted to maintain focus in all planes, sometimes resorting to special-effects shots to do so. The Soviets valued fixed focus as well, as several shots above suggest. It could be maintained if the foreground plane wasn’t too close, and the depth of field would control focus in the distance. Hence many shots use distant depth. At one point in The Great Citizen, when a woman interrupts a meeting, the official in the foreground trots all the way to the rear to meet her.

The sense of cavernous distance is amplified by the wide-angle lens.

But sometimes pinpoint focus in all planes wasn’t the goal. Another way to activate depth was to rack focus. In this scene of Rainbow (1944), the man who has betrayed the village comes home and discovers a delegation waiting to try him. At first they’re out of focus, but when he turns they become visible.

Focused or not, some of these shots push important action to the edge of visibility in a way that would be rare in American cinema. In A Great Life, a snooper is centered but sliced off by a window frame and kept out of focus, while a trial scene is interrupted by a figure far in the distance who bursts in to announce a mine collapse.

The Great Citizen shows Shakhov discussing a suspect, who hovers barely discernible in the background over his left shoulder. I enlarge the fellow and brighten the image.

This makes Wyler’s sleeve-shot in The Little Foxes seem a little obvious.

The Great Whatsis and the masters of the 1920s

The New Moscow (1938).

If American movies favor titles called The Big …., the Soviets liked The Great …. (Velikiy). But The Big Sleep doesn’t look all that big, and The Big Sick is big only to a few people, and The Big Knife doesn’t even have a knife. In the USSR, calling something big summoned up monumentality. Stalinist culture was grandiose in its architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and even music, with symphonies of Mahlerian length and oratorios boasting hundreds of voices.

Accordingly, one effect of the depth aesthetic was to grant the characters and their settings a looming grandeur. Earth-changing historical events were being played out on a vast stage that framing and set design put before us.

Naturally, battles are on a colossal scale. Napoleon broods in the foreground (Kutuzov) and troops march endlessly to the horizon (The Vow).

1940s films feature wartime landscapes on a scale almost unknown to Hollywood. If God favors the biggest battalions, God would seem to love the Russians (a prospect that otherwise seems invalidated by history). Below: The Battle of Stalingrad.

These landscapes are surveyed in long tracking shots, a habit that survived in Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1966-1967).

Soviet forces command impressive headquarters (The Great Change, 1945), perhaps necessary to balance the Nazis’ resources (The Vow).

Parlors and committee rooms are remarkably big, and even prison cells (The Young Guard Part 2) and farmhouses (The Vow) have plenty of room.

Gigantism wasn’t unknown in 1920s cinema, or in Russian painting both classic and recent. The Vow seems to justify its scale by reference to a Repin painting, which the characters see on display.

Not only were the 1920s silent classics monumental; they became monuments. Masha records the veneration that the “master” directors felt for the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, Barnet, and other predecessors. Moments in the Stalinist cinema seem to refer back to that era. The Battle of Stalingrad evokes the mother with the slain child on the Odessa Steps, and The Vow has the nerve to superimpose on Stalin (friend of farmers) an image of concentric plowing from Old and New.

These can be taken as cynical ripoffs, but in a way they testify to the fact that great silent films had forged some enduring iconography.

VIP: Very important, Pudovkin

You don’t hear much about Pudovkin’s 1930s and 1940s films, but they can be exuberantly strange. Eisenstein aside, he stands in my viewing as the director who played around most ambitiously with the academic style. Perhaps he was encouraged in this by his young codirector Mikhail Doller, but Pudovkin had already tried out some audacious strokes in A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933).

For a high Stalinist example take Minin and Pozharsky (1939). This tale of seventeenth-century warfare seems virtually a reply to Alexander Nevsky (1938), as Mother (1926) responded to Strike (1925). Minin opens with statuesque staging reminiscent of Eisenstein’s film, but the scene is handled in telephoto shots and to-camera address. The combat scenes employ handheld battle shots, along with close-ups of fighters and horsemen that aren’t stylized in the Nevsky manner.

But there’s more than pastiche here. One battle shows the Russian forces rushing from the left in tight tracking shots, while the enemy forces move from the right in panning telephoto. Especially striking are axial cuts, beloved of Soviet filmmakers for static arrays, employed in movement. Horses sweep past a tent in extreme long-shot; they smash into the tent in long shot; and in a closer view the tent lies trampled as other horses continue to flash through the foreground.

The shots are 50 frames, 38 frames, and 13 frames respectively. For a moment, we might be back in the great era of Soviet editing.

Victory from 1938 is a drama in which aviators set out to rescue an interrupted around-the-world flight. Here Pudovkin and Doller invoke the depth staging of the era only to disrupt it with what we might call “smear” cuts.

During the parade for the departing airmen, for instance, a young man happily tossing papers, in another grotesque wide-angle shot. He’s blocked by a man passing through the frame. Match on action cut to another figure, close to the camera and moving in the same direction. This figure wipes away to reveal a man reading a newspaper.

This sort of weird graphic match becomes a stylistic motif in the film. Later, when the rescue has been completed, another crowd scene yields a similar pattern of depth smeared and exposed. A shot of the parade is sheared off by a woman’s passing face. That cuts to a man’s passing face, which moves away to show the crowd behind him.

The patterning pays off when the victorious plane rolls triumphantly through the frame, blotting out the image, to be graphically matched by a passing figure who unveils the pilot’s mother embracing him.

In Admiral Nakhimov (1947) Pudovkin and Doller employ the smear-cutting technique during a battle scene. Stills are totally unable to capture the way this looks. Soldiers charge up a hill, and their falling bodies, briefly blocking the camera’s view, are given in jump-cut repetitions that suggest, through a spasmodic rhythm, the sheer difficulty of advancing.

Even stranger is the moment when soldiers rush toward a distant fortification, with a latticework basket in the foreground. Cut to the hill edge, with a comparable blob moving leftward through the frame. It turns out to be a fighter’s shoulder.

The oddest part is that this second shot is only six frames long, and every frame after the first is a jump cut; that is, some frames have been dropped as the blob makes its way across the image. The effect on your eye is percussive, and seems to be anticipated by Pudovkin’s experiments in popping black frames into shots in A Simple Case. What kind of director thinks like this?

Of course these Pudovkin/Doller films also subscribe to the official look, with monumental depth staging. The films acknowledge the 1920s tradition as well. Admiral Nakhimov casts a personal look back to Pudovkin’s great rival. A shot of the crew’s tautly bulging hammocks recalls, maybe cites, the crew’s sleeping area of Potemkin.

In Odessa, Admiral Nakhimov echoes Potemkin even more strongly. We get waving crowds, the stone lions, and a reminder of those famous steps.

In sum, the Stalinist cinema holds a unique interest for students of the history of film style. Not only did it apparently constitute a significant development in technique, but in forming a tradition, it provided a counterpart and sometimes a counterpoint to developments in the West. Later that tradition became something for directors to react against (Tarkovsky and Sokurov come to mind) or to adapt to new purposes (I’d put Jancsó in that category). For all the behind-the-scenes bungling, it became much more than a propaganda vehicle.

Scholars who study Stalinist film are usually impelled by an interest in propaganda or an interest in the audience’s response. My questions were different. I was driven by my interest in Eisenstein and comparative stylistics. So I tried to investigate the formal and stylistic norms of Soviet cinema. Some of those norms Eisenstein helped create, and then revised for his own ends.

Still, I feel like a butterfly collector picking out vivid specimens for an expert to explain. I can’t supply the hows and whys. How did filmmakers manage to create these remarkable images? What technical resources, of lenses and lighting rigs and film stock and set design, permitted them to craft these striking shots? Were their peers and masters insensitive to this official look? Was it taken for granted? Or was it self-consciously promoted and taught? Some of these schemas are developed in Eisenstein’s lectures at the Soviet film school. And how, at a more micro-level, do these patterns function in the individual films?

As for the whys: Why did filmmakers embrace these options rather than others? And why did they develop, sometimes apparently in a spirit of play, some oddball technical innovations?

Such questions seem to me compelled by films that turn out to be more artistically interesting than most commentators have noted. One of the most corrupt and brutal political systems in world history produced films of considerable interest, and a few of enduring value. I hope experts try to figure this all out. I bet Masha Belodubrovskaya will lead the way. Her new book is a splendid start.

Masha is no stranger to this blog, having translated Viktor Shklovsky’s remarkable “Monument to a Scientific Error” for us.

This is a good place to thank all the people who helped me see Stalinist films in archives over the decades. That number includes Gabrielle Claes, Nicola Mazzanti, and the late Jacques Ledoux of the Belgian Cinematek; Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, and Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum; and Pat Loughney, then of the Library of Congress.

I learned of Ermler’s “conversational cinema” (razgovornyi kinematograf) from Julie A. Cassiday’s “Kirov and Death in The Great Citizen: The Fatal Consequences of Linguistic Mediation,” Slavic Review 64, 4 (Winter 2005), 801-804. The depth aesthetic of high Stalinist cinema proved valuable when 1960s bureaucrats decided to make Stalin disappear. See our online supplement to Film History: An Introduction.

There are more examples of “Stalinist formalism” in On the History of Film Style–recently declared out of print, but soon to appear in a new electronic edition on this site. See also my Cinema of Eisenstein for arguments about how he created and then swerved from some of his peers’ norms.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Eisenstein on his birthday. But they make him a slim, hip metrosexual. Revisionism can go too far.

Kelley Conway, Masha, and Scott Gehlbach, at a party last night celebrating Masha’s book–and her winning tenure! Kelley’s contributions to our blog are here and here and here.

Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017

Silence.

DB here:

This is a sequel to an entry posted a year ago. Like many sequels, it replays the ending of the original.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Parts of those histories are traced in the book that came out in the fall, Reinventing Hollywood. Some of my blog entries have already served to back up one point I tried to make there: that contemporary filmmakers are still relying on the storytelling techniques that crystallized in American studio films of the 1940s.

Relying on here means not only utilizing but also, sometimes, recasting. In keeping with earlier entries (including one from the year before last), I want to explore some films from 2017. These show that the process of schema and revision creates a tradition. Hollywood is constantly recycling, and sometimes revitalizing, Hollywood.

Of course here be spoilers.

Back to basics

The Big Sick.

The US films I’ll be considering all adhere to canons of classical Hollywood construction. Some of these are laid out in the third chapter of Reinventing.

Classically constructed films have goal-oriented protagonists who encounter obstacles, usually in the form of other characters. The goals are often double, involving both romantic fulfillment and achievement in some other sphere. (Somewhere Godard says that love and work are the only things that matter. Hollywood often thinks so too.) Alternatively, the goal might be prodding someone else to action (Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri). Often there’s a clash between the goals, as when work tugs the protagonist away from love (La La Land).

The plot is typically laid out in large-scale parts. A setup is followed by a complicating action that redefines character goals. In Downsizing, once Paul has gotten small, he has to reconceive his goals in the face of his wife’s last-minute defection from their plan. There follows a development section that delays goal achievement through characterization episodes, backstory, subplots, parallels, setbacks, digressions, twists, and new obstacles. That marvelous slab of show-biz schmaltz, The Greatest Showman, relies for its development on a potential love triangle and a secondary couple’s romantic intrigue.

There follows a deadline-driven climax that resolves the action and an epilogue (sometimes called the tag) that celebrates the stable state achieved and perhaps wraps up a motif or two. The Greatest Showman presents Barnum’s success in creating a genuine circus and reconciling with his family. The tag shows a big production number, with the subplot resolved (Carlyle embracing Anne) and the motif of swirling points of light—initiated in Barnum’s spinning Dreams gadget—washing over the final spectacle and his daughter’s ballet performance.

Classical narration—what’s usually called point of view—typically attaches us to the main characters. But not absolutely: we’re usually given access to things they don’t know, mostly for the sake of arousing curiosity and suspense. And throughout, the film is bound together through recurring motifs that reveal character (and character change) or significant plot information. Think of the roles Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 assigns to “Brandy, You’re a Fine Girl,” Pac-Man, David Hasselhoff, and that “unspoken thing.”

Or take The Big Sick, a semi-serious romantic comedy. Kumail’s initial goal is success in standup comedy, but he also falls in love with Emily. His Pakistani-American family constitutes the main antagonist, as his mother and father want him to go to law school and submit to an arranged marriage. He hasn’t told his family about Emily, which precipitates the couple’s big quarrel: “I can’t lose my family.” Kumail’s goal shifts when Emily is stricken by a mysterious disease. In the development section , as she lies in a coma, he gets to know her parents, and a tense sympathy develops between them. The crisis comes when Kumail confesses his true goals to his parents, they disown him, and Emily’s disease hits a life-threatening phase.

In the climax portion, Emily revives and breaks off with him, his parents grudgingly accept his move to New York, and he mounts a somewhat successful one-man show there. The film is tightly tied to Kumail’s range of knowledge, so we’re surprised when he is—as when Emily’s parents decide to move her to another hospital, and when Emily pops up in his New York audience, ready to reconcile with him.

The Big Sick exploits many comic motifs: the parade of would-be fiancées Kumail’s mother invites to dinner, the photos he keeps of them (which ignite Emily’s jealousy), the repeated sit-downs he has with his family, the dumb catchphrases deployed by other comics, and especially Emily’s “Woo-hoo!” heckling, which eventually attests to the rekindling of their love.

The power of classical plotting is shown in its ability to spotlight a Pakistani-American protagonist, an Islamic family demanding that a son adhere to tradition, and the pathos of parents facing the death of a daughter. But that ability to flexibly absorb new subjects and themes and emotional registers has kept the classical template going for about a century.

Time travel

Wonder Woman.

One of the hallmarks of Forties cinema, I argue in Reinventing’s second chapter, is a eagerness to explore what flashbacks can do. Flashbacks were already well-established, but a more pervasive acceptance of nonlinear storytelling, so familiar to us now, became firmly part of Hollywood sound cinema in this period.

One-off flashbacks are so common now we don’t particularly notice them. In The Big Sick, when Kumail visits Emily’s apartment with her parents, he peeks into her closet, and we get glimpses of her wearing the outfits earlier in the film. In this case, flashbacks function as memories. At the climax of Guardians 2, Quill flashes back to moments of listening to music with his mother. Similarly, in Get Out, Chris recalls his childhood TV viewing and, at the climax, he remembers earlier moments at the Armitage garden party when he asks, “Why black people?”

Flashbacks usually aren’t pure representations of memory, though. They often include information that the character doesn’t or couldn’t know. In fact many flashbacks are addressed simply to us, coming “from the film” rather than from a character’s mind. These may remind us of things already seen, or fill in gaps, or plant hints about things that will develop.

So, for instance, in Logan Lucky, when Logan says, “I know how to move the money,” we get a flashback to him studying the pneumatic pipes that feature in the heist plan.

He’s not necessarily recalling the moment; the filmic narration seems merely to be tipping us the wink. At the climax, other “external” flashbacks plug gaps we didn’t notice earlier. These reveal some aspects of the heist we weren’t aware of, such as the extra bags of money carried off.

1940s filmmakers also explored how flashbacks could be “architectonic,” how they could inform the overall shape of the movie. Here the flashback rearranges story order to build up curiosity and suspense, and it may come from purely from the narration or be motivated as character memory.

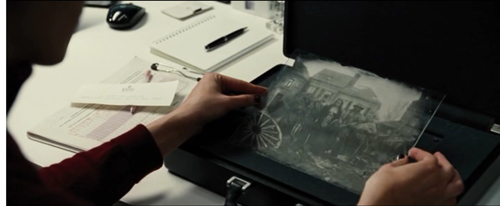

One large-scale pattern is the extensive embedded flashback, as in How Green Was My Valley, I Remember Mama, and innumerable biopics. Wonder Woman gives us a framed inset of this sort, when a modern-day Diana opens the chest harboring the World War I photo. That scene segues to the past. The origin story and war episodes are ultimately closed off by a return to the present, and a reminder of a motif—Steve’s watch (which, in one of the film’s jokes, stands in for something more private). The purpose of this is to provide what I call in the book “hindsight bias.” While building curiosity about the past, the opening primes us to expect certain things to have been inevitable (such as chance meetings).

Another common framing strategy begins at the climax and then a long flashback lays out the conditions that led up to it. A reliable source tells me that Pitch Perfect 3 does this, starting with an explosion followed by a title announcing that the action began three weeks earlier. In films like this, there may be no closing frame; the internal action of the flashback catches up, perhaps via a replay, with what we saw at the outset, and the film proceeds to the resolution and epilogue. The somewhat phantasmic opening number of The Greatest Showman comes to fruition during the finale.

To and fro

Loving Vincent.

Sustained blocks like this are fairly rare nowadays, I think. More common, as in the Forties, is an alternation of past and present. The main examples in Reinventing Hollywood include Passage to Marseille, The Locket, Lydia, Kitty Foyle, and Sorry, Wrong Number. Again, though, these are motivated as memories, while current examples tend to be more “objective.”

A simple instance is Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. Here clusters of events in 1981 alternate with incidents in 1979: Gloria Grahame returns to her young lover, and we flash back to their earlier affair. Neither protagonist is firmly established as recalling the 1919 events. Another feature of 1940s flashbacks, the replay from different viewpoints, comes in here as well. The couple’s crucial quarrel in New York is shown first from Peter’s perspective, and later from Gloria’s. He suspects her of infidelity, but we learn that her secret involves her cancer. As often happens, our restriction to the protagonist is modified by knowledge he doesn’t gain at the moment.

The alternation of past and present is given a more geometrical neatness in Wonderstruck. In maniacally precise parallels, Rose in 1927 runs away to Manhattan to find her mother, while in 1977 Ben runs there to find his father.

The parallels are reinforced by a host of motifs: wolves, movie references, the asteroid in the Museum of Natural History, a bookmark, and so on. The linear chronology gets straightened out, and the gaps filled, by an integrative flashback played out among miniatures and cutouts adapted to the scale model of Manhattan. The dovetailing flashbacks create a sense of cosmic design; in many films, convergences like these can suggest destiny.

For modern audiences, Citizen Kane is the prototypical flashback film of the 1940s, and its investigation structure, while not completely original, was hugely influential. I was surprised to see Kane’s schema revived this year in Loving Vincent. Once the postman has given Armand his mission, to take Vincent’s last letter to brother Theo, we embark on an inquiry into Vincent’s life and death. It’s refracted through the testimony of many who knew him during his sojourn in Arles. Armand’s goal gets recast when he learns of Theo’s death, but in the course of his travels he comes to understand how Vincent’s kindness and art touched many lives.

As in several Forties films, Loving Vincent’s past scenes jumbled out of chronological order, so we must piece together the story Armand gradually discloses. And there’s the driving force of mystery, a distinctive thrust in many Forties genres, for reasons I talk about in one chapter of Reinventing. Very modern, and not so much like the 1940s, is the brief, fragmentary quality of the flashbacks; I counted thirty-six of them.

The boldest experiment in nonlinear time I saw this year was Dunkirk. The film juxtaposes timelines consuming a week or so, a day, and an hour, and then aligns them in unexpected ways. In this staggered array, the distinction between flashbacks and flashforwards loses its force. Any cut may constitute a jump ahead of the moment just shown, or a jump back to an earlier incident. Christopher Nolan has acknowledged the influence of 1940s cinema on his thinking about time schemes, and here he explores yet again how crosscutting different lines of action can stretch or condense story duration.

Their eyes and ears

Get Out.

Like flashbacks, subjectively tinted storytelling has a long cinematic lineage. Silent films displayed dreams, visions, anticipations, and deformations of mind and eye. Those devices mostly dropped out of 1930s American cinema, which was to some extent more “objective” and “theatrical” in its mode of presentation. Subjectivity came roaring back in the Forties, which is why Reinventing Hollywood devotes two chapters and several other passages to various techniques that go beneath the surface.

Memory-based flashbacks are common options today, but the inward plunge can take other forms. For most of its length, Get Out restricts us to Chris’s range of knowledge, and it relies on optical POV in many stretches. Through his eyes we see Mrs. Armitage staring at him while stirring the tea.

More complex is his view of Georgina at the upper window. That’s followed by a shot going beyond his range of knowledge: she’s looking not at him but herself.

We take a deeper dive into Chris’s mind under hypnosis. The boy Chris sinks into a stellar cavity and becomes Chris staring at Mrs. Armitage as if she were appearing on the TV screen. The shift dramatizes his guilt at his mother’s death and his susceptibility to this Bad Mom figure.

Once Chris becomes a prisoner, the narrational range widens again to show Rod’s efforts to rescue him, along with the family’s plans for him. But the film tightly realigns us with Chris at the climax, so that the attacks from Rose, Jeremy, and others come as surprises.

Chris, a photographer, channels his experience through vision, though the hypnotism scene blends sounds from the present with the rain drizzling in the past. Subjectivity goes more fully sonic in Baby Driver, about a whey-faced lad who lives in the auditory ether.

Edgar Wright, now exercising straight the percussive dashboard details he parodied in Hot Fuzz, punches up the visual exhilaration of Baby’s rubber-shredding takeoffs and getaway 180s. He locks us into Baby’s auditory world as well. We’re almost completely attached to Baby, learning what he learns when he learns it. Notably, the robberies are rendered from his perspective, including optical POV shots as he waits in the getaway car.

Again, fragmentary flashbacks replay his mother’s death and the childhood damage to his hearing. We even get a fantasy, with Baby imagining his escape with Debora in black and white.

What’s just as subjective, though, is the music Baby incessantly cues up on his iPod. Blocking out the shriek of his tinnitus, it provides a soundtrack to his life—danceable tunes as he bops down the street, ballads when he flirts and falls in love with Debora, and pulsing rock during robberies (what the psycho Bats calls, “a score for a score”). Through volume and texture, Wright suggests that we hear the music as Baby does; only the loudest environmental sounds poke through. Sometimes, when he pulls out one earbud, the volume drops. His growing attachment to Debora is signaled by his dialing up a song using her name and sharing his precious buds.

Some scenes are handled objectively, as we witness the gang’s conversations in front of Baby. He can read lips, though, and he can keep the iPod cranked up. So a little bit of Baby’s custom soundtrack leaks in for us underneath others’ dialogue. At other times, the score takes over to become nondiegetic accompaniment, as when gunshots in a firefight land on the off-beats of “Tequila.”

As you’d expect, the music comments on the action throughout (“Never ever gonna give you up” when Baby defends Debora from Buddy) and supplies motifs. Queen’s “Brighton Rock,” Baby’s favorite heist accompaniment, briefly enables him to bond with Buddy.

A song about a couple’s devotion reminds us that both thieves are loyal to their women.

Momentary sound changes are rendered through our protagonist’s viewpoint. Wright lets us hear the whine of Baby’s tinnitus as Bats taps his ear. When Buddy blasts his pistols alongside Baby’s head, we suffer his hearing loss and the distorted voices that wobble through it.

Such streams of auditory perception occasionally emerged in early talkies (e.g., Gance’s Beethoven). Those experiments got normalized in 1940s manipulations of sound perspective in different environments. More fancily, in A Double Life (1947), party chatter subsides when the hero covers his ears, and in Pickup (1951), the gradually deafening protagonist hears high-pitched noises. Wright extends these one-off devices to the texture of an entire film.

Confidants

The Keys of the Kingdom (1945).

Large-scale and small-scale, the heritage of the 1940s seems to be everywhere. Many of the flashbacks and fantasies I mentioned already are primed by a track-in to a character’s face, just as in classic studio pictures. There’s also block construction, either unsignaled as in the Wonder Woman and Greatest Showman cases, or signaled, as in the date-stamping in the early alternations of Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. We also get explicit chaptering, as in The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) and Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer.

Voice-overs come along with flashbacks, as a way of guiding the audience to understand the time shifts. In the Forties, as I discuss in the book’s sixth chapter, voice-overs became more flexible and fluid. Sometimes they were external, issued from an all-knowing commentator (Naked City and other police procedurals). Sometimes they were sonic equivalents for letters and diaries, letting us in on what characters were writing. Deeper intimacy could come from voice-overs serving as inner monologues, the voice of a character’s mind. These, like flashbacks, are associated with film noir, but also like flashbacks they actually emerge in many genres–as they do today.

The voice-over can be perfunctory, as in All the Money in the World. Young Paul Getty, kidnapped in the opening reel, has a couple passages confiding in us, but he’s not heard from again. Moreover, his explanation of his grandfather’s rise to power (during the inevitable flashbacks) could have been supplied in other ways. Paul baldly tells us that we need to know all this to understand what follows (who’s he talking to?). He admits that he’s an expository shortcut. This is why voice-over is sometimes considered lazy storytelling.

It doesn’t have to be. Take Martin Scorsese’s Silence. In subject and strategy it reminded me of The Keys of the Kingdom (1945), which dramatizes the diary of a young missionary to China. Via this novelistic device, we get flashbacks to his youth and his years of service. We get as well the reaction of the skeptical priest whose voice reads the journal. This fairly straightforward schema is in effect revised by Scorsese and co-screenwriter Jay Cocks, who create a floating dialogue among voice-overs.

After initial exposition via an old letter from Father Ferreira, which is recited in his voice, two young priests set out for Japan. They hope to maintain the clandestine Christian community there, and they want as well to discover if Ferreira has truly renounced his faith . The bulk of their grim adventures is commented on through the voice-over of one of them, Father Sebastião Rodrigues. At first he’s vocalizing a letter, which he calls a report, summing up the struggles of the Jesuit mission and their encounters with Christian villagers. In the course of his report, we also get an embedded flashback narrated by Kichijiro, their guide and a sporadically lapsed believer himself.

But at a crucial moment, Father Sebastião’s report ceases to be such and turns into an inner monologue. Seeing a Christian village devastated by the shogun’s forces, he asks, “What have I done for Christ?”

Soon his voice presents a kind of stream of consciousness–praying for the villagers as they walk off in captivity, thanking God when he has a vision of Jesus on his prison wall. His inner voice urges his colleague Father Garupe, severely tortured, to apostatize.

In last stretch of the film, new voices are heard. There’s Jesus, perhaps filtered through Sebastião’s mind (subjectivity again), and then, more objectively, there’s an account from the Dutch trader Albrecht. He drily reports that Sebastião apostatized and followed Ferreira in leading a Japanese life. Albrecht’s narration is interrupted by a dialogue between Sebastião and Jesus, capped by the priest’s blurting out: “It was in the silence that I heard your voice.” Albrecht’s voice-over concludes the film, with his final claim that the priest was “lost to God” belied by the closing image.

From the 1940s onward, voice-over has been a rich resource–describing settings and external behavior, judging other characters’ motives, giving us access to the deepest thoughts of the speaker. I try to show these capacities at work in a fairly ordinary film, The Miniver Story, but for our time, the soundtrack of Silence is another vivid demo. In the juxtaposition of different voices, it achieves some of the density of a novel, and by the end we better understand the initial words and emotions of Father Ferreira, the priest whose apostasy launches the plot.

Passed-along voice-over gets a bigger workout in Dee Rees’s Mudbound. The original novel is somewhat like As I Lay Dying; its sections set various characters’ voices side by side, shifting viewpoint as each takes up a portion of the tale. Constant commentary and perfect alignment with a character’s range of knowledge are hard to sustain in cinema, so what we have onscreen are objectively presented scenes accompanied by an occasional voice-over. Still, it’s a rare option. If Silence gradually opens its voice-over horizons near the film’s end, Mudbound introduces polyphony from the start. Six characters share their thoughts and feelings in alternation, providing backstory and deepening our access to their reactions.

As in Silence, there’s a pattern to the voice-overs. The bulk of the film is an embedded flashback, triggered by the McAllen brothers setting out to bury their father and encountering the Jackson family riding by.

The intersection of two families sets up not only the flashback episodes but the floating voice-overs. As the visuals anchor us initially to the white family, the first voice-overs issue from Laura, the wife of Henry McAllen, and from Henry’s brother Jamie. In the flashback stretch, as America enters World War II, the voice-overs shift to the Jacksons, the father Hap and the mother Florence. The plot proceeds to add the voices of Henry and the Jacksons’ oldest son Ronsel. All the characters narrate the action in the past tense, as if recalling it from a distance in time, but no listener is ever specified–a common feature of voice-overs in the 1940s and afterward.

During the film’s second half, the development and climax sections, the voice-overs nearly vanish. For over an hour, we hear only Laura and Florence, and only once apiece. Jamie and Ronsel, both disaffected returning vets, don’t confide in us during their growing friendship or during the persecution of Ronsel by the local white men. The women are left to provide a sporadic chorus.

At the end, however, a spurt of brief commentaries give the men their inner voices back. We return to the present and see Hap Jackson help the McAllen men bury their father (the inciter of KKK violence against Ronsel). The epilogue features brief comments from Ronsel, Jamie, and Hap, and not the women. Ronsel gets the last word. Ironically, because of the KKK savagery, this narrator has become mute.

Again, I felt a current film’s kinship to those I studied for the book. Mudbound traces the rural home front, the military experiences of a white man and a black one, and the veterans’ problems of adjustment upon returning home. These elements hark back to some of the powerful films of the 1940s, including Home of the Brave and The Best Years of Our Lives. The sympathetic portrait of African-American families isn’t unprecedented either, as seen in Intruder in the Dust and Lost Boundaries. Mudbound‘s passed-along narration, like the ones we find in other modern films, constitute contemporary revisions of the shifting voice-overs we get in Citizen Kane and All About Eve.

Career women careening

Molly’s Game.

Molly’s Game and I, Tonya offer good wrapup examples of many of these strategies, with some unreliability thrown in.

As you’d expect in a film by Aaron Sorkin, the flashback organization of Molly’s Game is fairly complicated. Just as The Social Network intercut two arrays of flashbacks triggered by two legal inquiries, the new film scrambles together crucial moments in Molly’s childhood , scenes of her current legal troubles, and sequences showing her rise to become the Poker Princess, the arranger of high-stakes games. The film gains a bit of the structural symmetry of Wonder Woman by beginning and ending with a childhood defeat that Molly rises above.

The flashbacks are stitched together by Molly’s voice-over. A filmmaker who recruits a narrating voice has to choose. Do you show the narrating situation? Or do you leave it unspecified? In this last instance, the narration might be wholly internal, a mental summing up of events, or it might feel like a confidence shared with an intimate, even though we’re shown no listeners. In Molly’s Game, her bare-it-all confession might seem to be simply her unspoken thoughts, but at one point it’s suggested that what we’re getting is her book’s version of her life.

Molly’s attorney Charlie is reading her memoir while he researches her case, and he asks her about a passage we saw in a flashback: her boss chews her out for bringing him “poor people’s bagels.” The attorney suggests that nobody uses that phrase, and that probably the boss used a racial slur that she suppressed in the book. This throws a little bit into question the reliability of Molly’s flashback, while also hinting at something we learn later: she sanitized the book to spare the reputations of the high rollers she serviced.

I, Tonya takes another option. Again there are disordered flashbacks and bursts of subjectivity tied together by the voice track. Whereas Molly is the sole speaker in her film, though, Tonya shares the soundtrack with other characters, in the manner of Mudbound. But these commentaries aren’t private musings. They’re the self-justifying testimony of people talking to a documentary camera. (Even though these sequences are said to be occurring forty years after the earliest events, the format is an anachronistic 4:3–presumably to help us keep the time frames distinct.

Once you get characters in conflict recounting past events, you have the possibility of disparate stories. Forties filmmakers exploited this in Thru Different Eyes and a certain Hitchcock film too famous to mention. Tonya says explicitly that there are different versions of the truth. A brief scene shows her battering Nancy Kerrigan, and a more complicated one occurs in a tale recounted by her husband Jeff. She fires a shotgun at him and turns to the camera saying, “I never did this”–before briskly ejecting a shell.

The comic possibilities of to-camera address on display here were exploited in My Life with Caroline, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, and other 1940s films. Then the momentary breaking of the fourth wall was reserved for the frame story and kept separate from the embedded flashbacks. But I, Tonya‘s revision is easy to understand as a zany equivalent for her verbalized denial. Given the defiant way she brandishes the gun, we’re permitted to doubt her denial–which means that the film is refusing to settle the matter. The possibility that the overall filmic narration could be unreliable was rehearsed occasionally in the Forties, perhaps most vividly in Mildred Pierce (analyzed here, sampled here).

Other paths

Foxtrot.

The 1940s were important for other national cinemas too. The book’s last chapter suggests that filmmakers in Britain, France, Mexico, and other countries engaged in similar narrative explorations–sometimes in imitation of America, sometimes on their own. I go on to suggest that eventually non-Hollywood narrative models came to international attention, and still later those affected American cinema.

Italian Neorealism was a prime source of alternatives. A good example of its long-term impact, I think, is The Florida Project, which embraces a slice-of-life pattern. Once you’re committed to episodic plotting, you need to organize the incidents coherently. Sean Baker follows European and US indie precedent in tracing a rhythm of daily routines that change in sync with the characters’ relationships. So Halley’s quarrel with her friend Ashley means that Moonee can no longer claim leftover food from the diner, which helps push Halley toward prostitution, which leads to the intervention of child welfare authorities.

The drama arises less from crisply defined goals than from circumstances that alter life routines. In addition, like many Neorealist films and others in this vein afterward, the poignancy gets sharpened by the presence of children caught up in adults’ bad choices.

The Florida Project presents many actions elliptically, leaving us to infer what has happened offscreen. (I think, for instance, that it’s motel manager Bobby Hicks who contacts the authorities, but I don’t think it’s made explicit.) Moving to films made outside the US, Michael Haneke’s Happy End takes ellipsis even further.

Haneke uses the strategy of delayed and distributed exposition. He presents some apparently casual events at the outset, then gradually reveals what’s actually going on, all the while tracing out ultimate consequences. Instead of presenting a clear-cut chain of causes and effects, he asks us to fill in unspoken plans, offscreen actions, and hidden motives. Haneke has specialized in suggesting how vague forces can disturb rich, smug families and their shady schemes. His mystery-driven narrational tactics suit Happy End as well as Code inconnu and Caché.

I speculate in Reinventing Hollywood that the European art cinema’s story-based mysteries and narrational uncertainties owe something to 1940s American films. So too perhaps does the use of block construction, which emerged in overseas portmanteau films of the postwar era (e.g., Dead of Night, Le Plaisir, The Gold of Naples). Samuel Maoz’s Foxtrot is a striking example of block construction.

His Lebanon (2009) took POV restriction to a limit by confining its action to a military tank in the heat of battle. (This tactic has Forties precedents as well, as Lifeboat and Rope remind us.) Foxtrot operates differently. Broken into three parts, it looks at a single situation–a young soldier’s duties at a checkpoint–through shifts in time and viewpoint. The opening shot, at first enigmatic, gets specified in an epilogue that recasts all that went before. Maoz also incorporates monotonous routines into his plot, the better to throw a single shocking incident into relief.

So classical construction isn’t the only option available. But other choices have histories as well. As viewers we learn these alternative stoytelling traditions, and we use that knowledge to make sense of new examples. No less than the Hollywood model, these other formal strategies engage us through familiar pattern and unexpected novelty, schema and revision.

I don’t mean to obsess over this 1940s thing. Our current films owe debts to silent cinema and to other eras too. It’s just that I continue to be fascinated by finding repetitions and variants of storytelling strategies that got consolidated in the period I was studying. Denounce them as formulaic if you want, but I prefer to think that these and other recent films illustrate, in fine grain, the continuity and sometimes the vitality of a major cinematic tradition.

Maybe this is my hook to an entry for the start of 2019?

Many thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics for help on this entry.

On the four-part structure of classical films see Kristin’s 2008 entry and my essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” Today’s entry deploys the analytical categories trotted out at length in this essay and more briefly in this discussion of The Wolf of Wall Street.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.